Chapter 10

FMD and Nutrition in the Prevention and Treatment of Alzheimer’s and Other Neurodegenerative Diseases*

[For their review of this chapter, I thank neurologist Markus Bock, a specialist in the application of the ketogenic diet and fasting-mimicking diet at the Experimental and Clinical Research Center, Charité–University Medicine Berlin, and Patrizio Odetti, chief of geriatrics at the University of Genova San Martino Hospital.]

BRAIN FUNCTION AND DAMAGE HAS LONG been a scholarly focus and passion of mine. As with aging, it represents a daunting scientific challenge. The brain is commonly afflicted by diseases, including Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s, that are devastating to sufferers and those around them. Yet I know and have spent time with many very elderly people who remain sharp and witty into their nineties and hundreds. My goal is to help as many people as possible live to a very old age with normal mental faculties. This chapter focuses mostly on Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias—specifically how nutrition and an FMD may affect their incidence and progression. Although Parkinson’s disease is also one of my research group’s areas of interest, we have not yet completed studies related to it. We have high hopes that the Longevity Diet and FMD will have beneficial effects on Parkinson’s, but it would be premature to speculate on possible outcomes before performing basic and clinical research on this disease.

Alzheimer’s Disease

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) accounts for 60 to 80 percent of all dementias. It is characterized by a loss of memory that interferes with normal daily tasks. In the early stages of the disease, patients have difficulty remembering newly acquired information. Later they become disoriented, show changes in mood and behavior, and often grow suspicious of family members or caregivers, whom they fail to recognize and remember. As the memory loss becomes severe, patients may have difficulty speaking, walking, and even swallowing.

When I first started working on AD in the laboratory of USC neurobiologist Caleb Finch in 1997, the great promise in combatting the disease was a vaccine against a protein called beta-amyloid, which accumulates in the brains of AD patients and which scientists generally agree is somehow involved in the disease, since it is linked to both the hereditary and nonhereditary forms. Twenty years later, this strategy has yet to produce any effective treatment, and hundreds of laboratories are still searching for a cure. It is also no longer clear that beta-amyloid accumulation has a primary causal role in the disease.

While we continue to search for a cure though, even a five-year delay in the average age of Alzheimer’s disease diagnosis would cut the number of patients by nearly half, since onset occurs at such an advanced age that many patients would die of another cause before developing the disease. Thus, AD is an excellent candidate for the use of dietary interventions such as the FMD, with wide effects on the aging process, which could delay AD onset or progression.

Prevention of Alzheimer’s Disease in Mice

Not surprisingly, the major risk factor for AD is aging. Incidence of the disease increases by more than a hundredfold from age sixty to age ninety-five. Mouse studies have provided a platform for understanding Alzheimer’s disease, since the human genes known to cause AD can be introduced into the mouse genome, promoting some of the memory loss and learning deficits observed in Alzheimer’s patients.

Again, it is sad that we must sacrifice mice to identify interventions for Alzheimer’s. But before we can begin human testing, we have no choice but to do preliminary tests in mice. It’s worth noting that the mice used in our AD studies do not appear to suffer; the cognitive decline caused by the mutations we introduce is similar to what occurs in humans with AD who reach very old age.

Thanks to these studies in mice, my group is now ready to start a clinical trial on the use of FMD in the prevention and treatment of AD together with a group of clinical geriatricians and neurologists at the University of Genova. We have already performed preliminary studies on the effects of the FMD on cognitive performance in normal participants and obtained positive and very promising results, which serve as a strong foundation for the Alzheimer studies. The point of this section is not to review all mouse studies related to diet and Alzheimer’s. Rather, the goal is to lay the foundation for specific diets in the prevention and treatment of neurodegenerative diseases.

Our first study attempted to delay the onset of Alzheimer’s disease by regulating the genes that accelerate aging. We used “triple transgenic” mice, which have three of the mutated human genes associated with Alzheimer’s disease (APP, PS1, and tau). Because AD in the great majority of cases occurs after age seventy, we opted against using a chronic low-calorie diet, since even if it proved effective, it could not be safely adopted by elderly people. We decided to regulate the activity of the two major sets of genes accelerating aging by tricking the cells, giving the mice a normal diet that lacked the nine essential amino acids (those the body cannot generate: isoleucine, leucine, lysine, methionine, phenylalanine, threonine, tryptophan, valine, and arginine). We also gave the mice excess quantities of the nonessential amino acids, which the human body can make and therefore does not need to obtain from the diet. In other words, the test diet was identical to the normal diet but contained fewer essential amino acids and more nonessential amino acids.

Starting at young to middle age, the mice received this diet every other week, alternating with a normal diet. The potent effect of this minimal change is obvious from the 75 percent reduction we detected in the levels of the pro-aging and cancer growth factor IGF-1 in the mice while on the diet. Notably, the effect of this dietary intervention on IGF-1 levels continued even after the mice returned to their normal diet. Months later, the mice placed on the protein-restricted diet every other week had better performance in several different cognitive tests, indicating that they were protected from Alzheimer’s disease symptoms.

These results are evidence of the potential of nutritechnology—that is, understanding the effect of food composition on specific genes and pathways in the quest for therapeutic diets that are minimally disruptive yet have effects comparable or superior to drug therapy. This is different from the concept of “nutraceuticals,” which in most cases are foods engineered for concentrated levels of particular molecules that have specific biological or medical functions. For example, concentrated vitamin C obtained from acerola can be considered a nutraceutical.

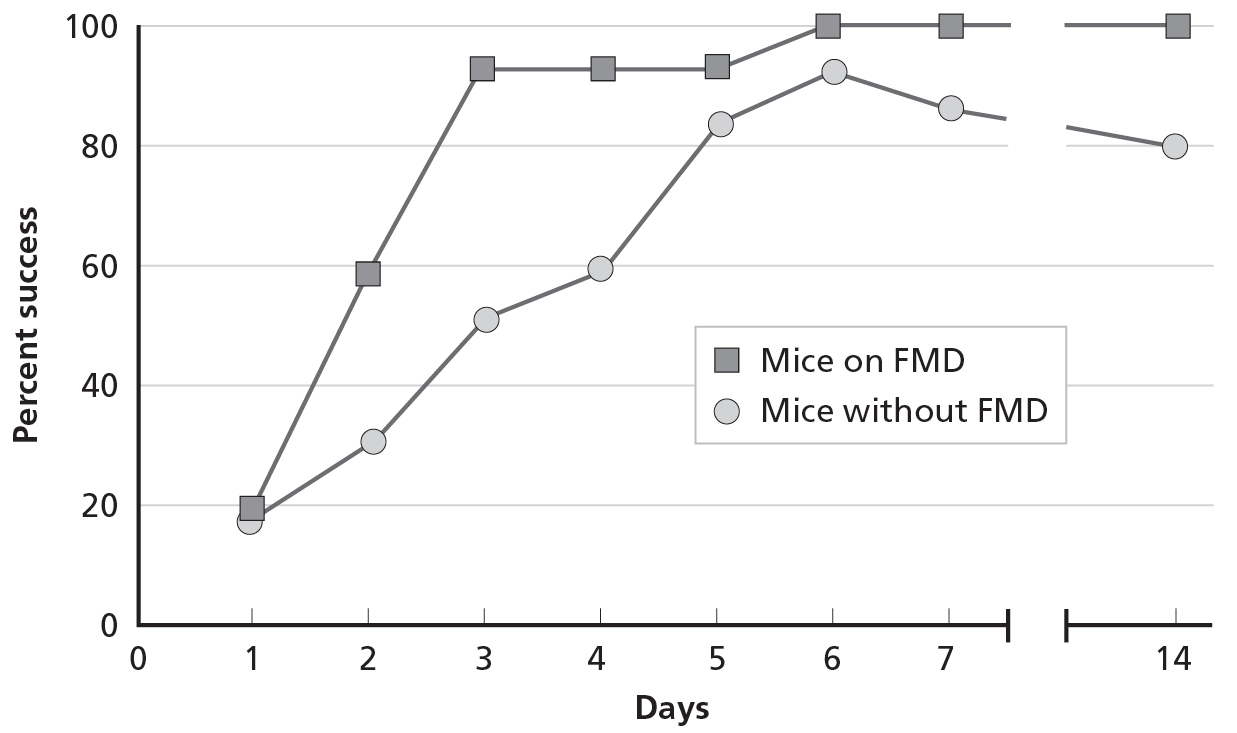

In a study I have already mentioned, mice received a reduced-calorie FMD for four-day cycles twice a month (eight days a month total), starting in middle age. In old age, these mice learned and remembered much better than mice in the control group (see fig. 10.1). We observed performance improvements in all tests, including motor coordination (on a rotating wheel), and both long-term and short-term memory.

10.1. Improvement of cognitive tests in mice exposed to fasting-mimicking diet cycles

The FMD cycles had profound effects on genes that play key roles in the aging process, including aging of the brain. Researchers at the US National Institute on Aging have performed many studies in this area, focusing on alternate-day fasting. Receiving no food one day and a normal diet the next day, these mice consistently showed improvements in learning and memory function. The benefits applied to both normal mice and mice with Alzheimer’s disease.1

We are now ready to begin clinical trials to test the effect of similar but less calorie-restricted diets in humans.

Dietary Prevention of Alzheimer’s Disease in Humans

The periodic FMD, because it promotes a longer and generally healthier lifespan, is recommended for most people, but because it provides a very low level of calories, it is not recommended for people over the age of seventy. What would be the point of adopting a diet that prevents Alzheimer’s disease if the same diet promoted a deficiency in the immune system or made the patient frail? Thus, before a dietary intervention can be recommended, it is imperative that its potential to prevent or treat a disease or condition outweighs its potential to cause adverse side effects. Thus, the minimal risks of using an FMD in a sixty-five-year-old would be justified if this person was at high risk for developing Alzheimer’s; this should be considered only until age seventy, or possibly older depending on the ability to maintain a normal weight and muscle mass, and based on the individual’s overall health status and the opinion of a neurologist. Notably, several studies indicate that a calorie-restricted diet improves and prevents loss of muscle mass in older animals and therefore further studies are needed to determine whether periodic FMDs would have positive or negative effects on muscle mass and strength in the elderly. With the availability of inexpensive and highly specific DNA testing, we can now also consider diets tailored for the prevention of a specific disease in individuals. For example, the APOE protein, responsible for carrying cholesterol and cholesterol-like molecules, comes in three forms: APOE2, APOE3, and APOE4. For people—particularly women—who have two copies of the APOE4 gene, the risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease is fifteen times higher than average. In the general population, the chance of having AD after age eighty-five is more than 40 percent; for someone with two copies (alleles) of the APOE4 gene, the risk shoots up to 91 percent—with half of them developing the disease by age sixty-eight.2 I encourage anyone whose parents or grandparents had Alzheimer’s disease to pursue genetic testing to determine if they have risk factors for the disease. If the tests come back positive, they may want to talk to their doctor about adopting the dietary recommendations that follow.

The Longevity Diet Plus Excess Olive Oil and Nuts

The periodic FMD may be effective in cognitive disease prevention in mice and possibly humans, but everyday diet also plays a central role in cognitive health. Although we are still conducting our studies into the positive effects of the Longevity Diet on neurodegenerative diseases, an everyday diet that has been shown to be protective against cognitive decline is the Mediterranean diet in combination with high levels of olive oil.3

A six-year study in Barcelona, Spain, originally designed as a cardiovascular study (and mentioned in the last chapter) monitored 447 volunteers (with a mean age of sixty-seven years) who were at high cardiovascular risk but cognitively healthy. Participants were randomly assigned to a Mediterranean diet supplemented with either extra virgin olive oil or 30 grams of nuts per day, or a control diet in which they were advised to reduce dietary fat. Participants on the Mediterranean diet plus olive oil or nuts performed better in cognitive testing than those on the low-fat control diet.4

In people over age sixty—and likely also in younger people—a Mediterranean diet supplemented with either olive oil or nuts is associated with improved cognitive function. However, an analysis of many studies on the Mediterranean diet and neurodegenerative diseases concluded that adherence to the Mediterranean diet only decreases the risk of neurodegenerative diseases by 13 percent.5 Thus, in order to optimize brain health and delay or prevent Alzheimer’s onset, I recommend the Longevity Diet plus additional nutrients including olive oil and nuts, as described below. Though the efficacy of this diet in the prevention of dementia has not been demonstrated yet, it has a higher potential for significant impact since it represents a stricter version of the Mediterranean diet and includes many additional nutrients of reported benefit.

Coffee and Coconut Oil

The role of coffee in health and longevity has been controversial. Although earlier studies included coffee as a risk factor for a variety of age-related diseases, including cancer and heart disease, later more careful studies indicate that moderate coffee consumption may in fact protect against diseases, including Parkinson’s, type 2 diabetes, and liver disease. A few studies suggest that coffee may also protect against Alzheimer’s.

Researchers at the University of South Carolina reviewed studies published between 1966 and 2014 assessing the relationship between coffee consumption and dementias. They examined eleven studies of a total of 29,000 participants. Overall, coffee drinkers and non–coffee drinkers showed no difference in their risk of developing dementia. However, the group with the highest coffee consumption had an approximately 30 percent reduction in the risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease. It is possible that drinking three or four cups of coffee a day may protect against Alzheimer’s, as it was shown to protect against Parkinson’s.6 This may be caused in part by coffee’s high polyphenol content. However, this type of coffee consumption could cause side effects, and its use should be considered only if you are at high risk for AD, and then under medical supervision.

Coconut oil contains high levels of saturated fat. But unlike other dietary saturated fats, which are composed mainly of long-chain fatty acids (fats with 13 to 21 carbons in the chain), coconut oil contains a high level of medium-chain fatty acids (MCFA, or fats with 6 to 12 carbons in the chain). MCFA are easily converted into ketone bodies, the same molecules produced at high levels during fasting. The brain begins to utilize ketones as a major source of energy during prolonged fasting periods and when glucose is scarce.

In a study of patients with Alzheimer’s disease, consumption of 40 milliliters (1.5 fluid ounces) per day of extra virgin coconut oil resulted in an improvement in cognitive status. This finding is consistent with other studies suggesting medium-chain fatty acids protect against dementia. While coconut oil’s protective role must be confirmed in large clinical studies, the published data indicates it may improve cognition in Alzheimer’s disease patients.7 Notably, the American Heart Association includes coconut oil among the potentially harmful foods containing saturated fats. Whether this concern is appropriate is hotly debated, but the possibility that regular use of coconut oil could increase cardiovascular disease should be considered when using it to prevent or treat dementias.

“Bad” Fats and Alzheimer’s Disease

While the medium-length fats in coconut oil and the mono-unsaturated fats in olive oil may protect against Alzheimer’s disease, the opposite is true of saturated and other fats, the “bad” fats, which may increase the risk of developing dementia in addition to cardiovascular disease. Several studies indicate that consuming high levels of saturated or trans fatty acids increases the risk of dementia. In studies conducted at the Chicago Health and Aging Project, consumption of saturated and trans fatty acids was associated with an increased risk of AD.8 These findings support adoption of the Longevity Diet, which is nearly free of the saturated fats and trans fats found in high quantities in animal-derived foods (especially red meat, butter, cheese, whole milk, pork, and candy).9

Sufficient Nourishment

Certain vitamins and other nutrients have been proposed to be neuroprotective—that is, capable of protecting neurons against damage. This view is probably simplistic, but some studies have implicated deficiencies in omega-3 fatty acids, B vitamins, and vitamins C, D, and E in brain aging and dementias. To date, most have failed to show a clear association between high-dose supplementation of these vitamins and nutrients and protection against dementias.

That said, every diet should contain a sufficient level of foods rich in all these nutrients (see appendix B for foods containing the highest levels of these nutrients). In fact, a review of studies indicates that AD patients have lower levels of folate and vitamins A, B12, C, and E. It would not be surprising if, in the future, certain deficiencies were found to contribute to AD. So while supplementing with high levels of vitamins or fatty acids may not be proven as protective, it avoids the risk of developing a deficiency, which could accelerate brain degeneration and dementias. Foods rich in vitamins may reduce the risk of AD but, for example, B vitamin supplementation was found to be largely ineffective, except in countries where food is not fortified with the folate vitamin.10

Age-Appropriate Weight and Abdominal Circumference

The association between body mass index (which takes into account a person’s weight relative to height) and cognition is complex and varies according to age. In younger and middle-age adults, a high BMI is associated with reduced cognition or a higher risk of dementia once these adults reach old age. However, a slightly higher BMI in older adults is associated with improved cognition and lower mortality. Thus, it is important to maintain a healthy weight and ideal abdominal circumference up to age sixty-five; beyond that point, the goal should be to reach the upper limit of the healthy BMI and abdominal circumference ranges. For men, a BMI in the 22 to 23 range may be ideal up to age sixty-five to seventy-five, but beyond that age, a BMI in the 23 to 25 range may be preferable in order to avoid loss of muscle mass and other detrimental deficiencies.

This goal could be achieved by adding small amounts of foods not permitted or very restricted under the Longevity Diet, such as eggs, goat’s or sheep’s cheese and yogurt, dark chocolate, fruit, and higher levels of fish and seafood. These foods should be consumed only in moderation even at older ages. Adding them to the Longevity Diet may help prevent weight loss and muscle loss, especially when protein consumption (0.4 grams of protein per pound of body weight) is combined with muscle training and exercise (see chapter 5).11

Dietary Treatment of Alzheimer’s Disease

Dietary interventions to prevent dementias—including coconut oil, olive oil, and the Longevity Diet—may also help patients with Alzheimer’s disease or a condition called mild cognitive impairment, which often precedes dementia.

Unlike their role in treating cancer, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease, however, the role of dietary interventions in the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias is little understood and still speculative. Because AD is devastating to patients and their families, and because most AD patients cannot afford to wait for future studies, I will describe the mouse studies we have completed and the studies we are about to perform in AD patients, which I believe have potential.

Again, the purpose of these interventions isn’t necessarily to cure AD but to try to delay its onset by five or ten years or more. Only a neurologist specialized in AD can determine whether any individual patient should try the diet. It must be understood that this is an unproven and risky strategy, which needs clinical testing in large trials before its safety and efficacy can be established. It would be best to try the following recommendations as part of an approved clinical trial.

As I mentioned, we had positive results in a mouse study alternating weeklong cycles of a protein-free diet supplemented with nonessential amino acids and weeklong cycles of a normal high-protein diet. With the input of an experienced neurologist, AD patients could try weekly cycles of a low-protein diet (0.1 to 0.15 grams of protein per pound of body weight) alternating with a relatively high-protein diet (0.45 grams of protein per pound of body weight). The patient would eat a diet based on carbohydrates and “good” fats (no meat, fish, eggs, milk, or cheese and low levels of legumes) for one week, followed by a normal and high-nourishment Longevity Diet the next week. The diet should include daily supplements of coconut oil (40 milliliters). During the “nourishment week,” salmon and other fish high in omega-3 oils (see appendix B) should be eaten at least three times a week, with care taken to avoid high-mercury fish.

Continue these week-on, week-off cycles of very low protein and normal protein for at least six months to see if (1) cognitive performance improves and (2) the patient maintains normal weight and muscle mass and does not develop other symptoms. If the patient loses more than 5 percent of body weight or muscle mass, further cycles of the diet should be delayed until the patient returns to a healthy weight.

Another admittedly risky option is to use the monthly FMD, which we have tested in people ages twenty to seventy but not in older subjects or in AD patients (see chapter 6). In a small and preliminary study, we observed improvements in cognitive performance in subjects who received three cycles of the monthly FMD. This is consistent with the strong effects of the twice-a-month FMD started in middle age on neural regeneration and the improved cognitive performance in mice once they reach old age.12

Note that FMD is potentially very risky in elderly subjects, especially those who are frail, are low-weight, or have lost weight during the progression of the disease. In the periods between FMD cycles, patients should follow a high-nourishment, plant- and fish-based diet that’s relatively high in protein (0.45 gram of protein per pound of body weight).

I emphasize once more that these interventions should be considered only in the absence of other viable options and based on the recommendation of a specialized neurologist, with the precautions and warnings listed above and preferably as part of a clinical trial.

Exercise Both Body and Mind

Remaining both physically and mentally active has been shown to protect against age-related dementias. A review of all the studies on exercise and dementia, covering eight hundred patients and eighteen randomized clinical trials, concluded that physical activity—particularly aerobic exercise, such as running and swimming—improves cognitive function in patients with dementia (see the exercise guidelines in chapter 5).13

Exercise is important in both the prevention and treatment of dementias. Naturally, for frail and older patients, a stationary bicycle may be more appropriate than running or swimming. Pedal resistance can be adjusted to achieve the right level of difficulty to challenge but avoid physical harm to the patient.

Another way to ward off AD and other dementias is to maintain brain activity. Reading, solving puzzles, and playing computer games have all been shown to improve cognition and help prevent or delay dementias.14

Summary: Prevention and Treatment of Neurodegenerative Diseases

Prevention

The following are guidelines for people at high risk of developing dementias (given family history or early cognitive decline):

- Adopt the Longevity Diet and the periodic FMD.

- Incorporate plenty of olive oil (50 milliliters per day) and nuts (30 grams per day).

- Drink coffee. For people at relatively low risk of AD, keep it to one or two cups a day; for people at high risk, drink up to three or four cups a day. Speak to your doctor if you have problems.

- Take 40 milliliters of coconut oil per day but consider potential heart disease risk (people with or at risk for cardiovascular disease should not use coconut oil).

- Avoid saturated fats and trans fats.

- Avoid all animal-based products with the exception of low-mercury fish and cheese or other dairy products from goat’s milk.

- Follow a high-nourishment diet containing omega-3, B vitamins, and vitamins C, D, and E.

- Take a multivitamin and mineral every day.

Treatment

The following are guidelines for people who have already been diagnosed with AD or dementia. This treatment plan must be approved and supervised by a neurologist and should be combined with standard of care.

- Follow all the dementia-prevention dietary recommendations above.

- Talk to your neurologist about following cycles of a protein- and essential amino acid–deficient diet followed by normal calorie intake and/or cycles of the periodic FMD.

With AD and other diseases that are later in onset, it’s important to remember that calorie- and nutrient-restricted diets are potentially dangerous to the elderly, so the neurologist on the case should work with a registered dietitian to optimize the effects on brain function while minimizing risks and side effects.

Although our studies into AD are perhaps the most speculative, this is an area I feel especially passionate about. By acting on the aging process using strategies like the Longevity Diet, it is possible to delay and even prevent diseases and remain as healthy as Emma Morano or Salvatore Caruso, who remembered well not only what they had done an hour earlier but also remembered many stories and even songs from their youth. This is my ambitious vision, and we’re working with labs and researchers around the world to help make it possible.