Chapter 11

FMD and Nutrition in the Prevention and Treatment of Inflammatory and Autoimmune Diseases*

[For their review of this chapter, I thank Kurt Hong, MD, PhD, associate professor and director of the USC Center for Clinical Nutrition, Los Angeles, and Andreas Michalsen, head physician, at the Experimental and Clinical Research Center, Charité–University Medicine Berlin.]

Aging and the Autoimmune System

As we age, we suffer damage to, or malfunction of, the cells of our immune system. White blood cells central to the immune system—including T cells, macrophages, and neutrophils—naturally produce inflammatory factors. These normally play a central role in coordinating many different healthy immune functions, ranging from combatting and killing bacteria and viruses to killing and disposing of damaged human cells, including cancer cells.

But as we get older, and also in association with disease, production of both immune cells and these inflammatory factors can become dysregulated. When this happens, inflammation can be activated even when it is not needed. This can result in a low-level systemic inflammation involving the entire body. In some cases, this inflammation is followed by the development of a strong immunity against normal cells or molecules within cells, resulting in a self-recognition, in which the immune system attacks parts of its own body—this is what occurs in autoimmune diseases such as multiple sclerosis, Crohn’s, and type 1 diabetes.

One way to determine whether someone has systemic inflammation—considered a risk factor for cancer and cardiovascular diseases, among other conditions—is to measure the level of C-reactive protein in the blood. The liver naturally produces CRP in response to systemic inflammation. Research shows that about a third of US adults have systemic inflammation as measured by CRP,1 but large portions of European and other populations are also affected—a consequence of normal aging and unhealthy behaviors, such as consumption of Western diets, obesity, and exposure to infection. Because the Mediterranean diet has been associated with a reduced risk of disease, many Europeans believe they are protected by their diet. Unfortunately, as I have shown in previous chapters, even the strictest form of the Mediterranean diet has a limited beneficial effect on aging and disease. And because most Europeans do not know what the Mediterranean diet entails, and also because adherence to the strictest form is difficult, it is seldom adopted even in the Mediterranean region.

A recent worldwide analysis revealed that between 8 and 9 percent of the global population has been diagnosed with one of the major twenty-nine autoimmune diseases2—the most common being type 1 diabetes, multiple sclerosis, Crohn’s disease, polymyalgia, psoriasis, lupus, and rheumatoid arthritis.

Alarmingly, the number of newly diagnosed cases of autoimmune diseases has been on the rise for the past thirty years. In the last decade, the incidence has jumped worldwide by a remarkable 19 percent a year.3 In other words, autoimmune diseases appear to be doubling in number every five years. While some of this increase can be attributed to improved diagnosis and awareness of certain conditions, it’s likely that environmental and dietary factors are also to blame.

Nutrition and Autoimmune Diseases

Obesity has been linked to multiple autoimmune diseases, including multiple sclerosis and rheumatoid arthritis. It may also be linked to Crohn’s and other autoimmune diseases of the gut.4 Because fat cells can be an important source of inflammatory molecules like TNF alpha and IL-6, the connection between obesity and autoimmune disorders could be related to abdominal fat. Fat accumulated in the abdomen and elsewhere in the body can generate molecules that stimulate immune responses, prompting immune cells to turn against other ordinary body cells.

High salt consumption is also believed to contribute to autoimmune diseases, possibly by promoting the activation of T cells—a central culprit in many autoimmune diseases. More studies are needed to confirm and understand the role of sodium in autoimmune disorders, but because salt is also involved in cardiovascular disease, moderation is generally recommended for those diagnosed with or at high risk for autoimmune diseases.

Diet can also affect the immune system by altering the bacteria population in the gut, which in turn regulates many different immune cells. It’s well established that the Western diet can have inflammatory, negative effects on the types of microbiota occupying the human gut.5 Research shows the bacterial population present in the gut of people eating an animal-based Western diet can be rapidly altered to a less inflammatory population simply by switching to a plant-based diet.6

At the Table with Your Ancestors

A less-understood potential factor explaining the rapid worldwide increase in autoimmune diseases may involve expanding choices in a modern, globalized food supply. My laboratory is only beginning to investigate this aspect of autoimmune diseases. We suspect, however, that certain aspects of today’s globalized diet may trigger autoimmune responses. For example, in a study, cow’s milk consumption in children was associated with elevated autoimmunity against the pancreatic cells that generate insulin, resulting in an increased risk for type 1 diabetes.7 Eventually, it will be possible to connect a person’s DNA (the genome) to the food he or she should avoid eating to prevent autoimmune disorders or intolerances. For now, my best advice is to “eat at the table of your ancestors.”

This means finding out where your parents, grandparents, and great-grandparents came from and what foods were common in those places. My ancestors are all from Italy, and because of this my diet is rich in tomatoes, green beans, garbanzo beans, and olive oil. Tomatoes are known to activate an immune response in a small minority of people, and they arrived in Italy only four hundred years ago, but that’s long enough that there is minimal risk that they will cause widespread autoimmunities or intolerances in today’s Italians. In contrast, a grandchild of Japanese or southern Italians, both populations without milk in their traditional historical adult diet, is likely to develop lactose intolerance as an adult.

If my grandparents were from Okinawa, I would include sweet potatoes and seaweeds in my diet; if they were from Germany, cabbage and asparagus. It seems complicated, but it’s not. It may require you to sit down with your parents or grandparents and ask questions, or ask an old person who used to live in the same area as your grandparents. Try to get the full list, since every component of their diet was probably selected to make up a full nourishment diet. Even though a little village like that of my parents in southern Italy did not conduct scientific studies to determine what diet was good or bad, everyone knew everyone else, and if someone developed vitamin B12 deficiency because they never ate fish or meat or eggs, everyone else in town would hear about it, and eventually learn how to avoid vitamin B12 deficiency. Similarly, if many babies who drank cow’s milk developed problems, people would eventually notice and switch their babies to goat’s milk. This type of food selection can happen more easily in villages and small towns, but it can also occur in cities if people live their whole lives in the same place. It would be much less likely to happen in the United States or in large cities like London or Tokyo, where communities are more transient and people know less about their neighbors’ diseases and food habits.

We do not yet have solid evidence that “eating at the table of your ancestors” will prevent diseases and make you live longer. And I’m not proposing that you eat exactly what your grandparents ate, rather that you match what they ate with the Longevity Diet described in this book.

When you don’t have the luxury of waiting until conclusive scientific and clinical studies are completed, it makes sense to adopt the best possible hypothesis using all the available information. In this case, the hypothesis is that a town of two thousand people and the surrounding towns—together with the doctors working in these towns—will be able to detect many of the advantages and disadvantages associated with particular foods by observing their effect over decades and by learning from their parents and grandparents. Much of the information will end up being correct. Some of it will be incorrect, but the risk of adopting this strategy is virtually zero—the food that was common and safe at the table of your ancestors is very unlikely to be harmful to you.

It’s also important to know what your ancestors didn’t eat. While the market may now be rich with so-called health foods and superfoods—ranging from kale to curcumin, quinoa to chia seeds—that can provide high levels of vitamins or protein, these varied ingredients and foods may be more harmful than helpful to people whose ancestors never consumed them. Quinoa, which originally comes from the Peruvian Andes, may be perfectly safe for people whose ancestors used it as a staple ingredient in their diet. It may also be fine for the great majority of people around the world. But it may lead to allergies, intolerances, and even autoimmune diseases in a small group of people—particularly those exposed to other factors contributing to autoimmune diseases. For example, quinoa was shown to increase the immune response in mice, which may be evidence of its potential to cause autoimmune diseases in humans,8 and it was shown to cause severe allergic reactions in multiple patients in the United States and France.9 Thus, if all your ancestors going back three hundred years lived in Germany, for example, it may be best to avoid “health foods” like quinoa and turmeric (curcumin), that historically were not key ingredients of the German diet.

Autoimmune Disease Treatment

The above-listed guidelines for the prevention of autoimmune diseases should also be adopted by patients undergoing disease treatment. In the following section, I focus on the use of FMD for the treatment of multiple sclerosis and rheumatoid arthritis—autoimmune diseases my group and others have investigated both in mouse studies and human clinical trials.

We have now tested the FMD with two additional major autoimmune diseases in mice. In both cases it worked surprisingly well, suggesting that FMD has the potential to reduce the severity of many autoimmune diseases. Please consider that these interventions are still under clinical or laboratory investigation and that, until larger clinical trials are completed, we cannot know whether they are effective in humans, nor can we exclude the possibility of severe side effects in a minority of patients.

Multiple Sclerosis

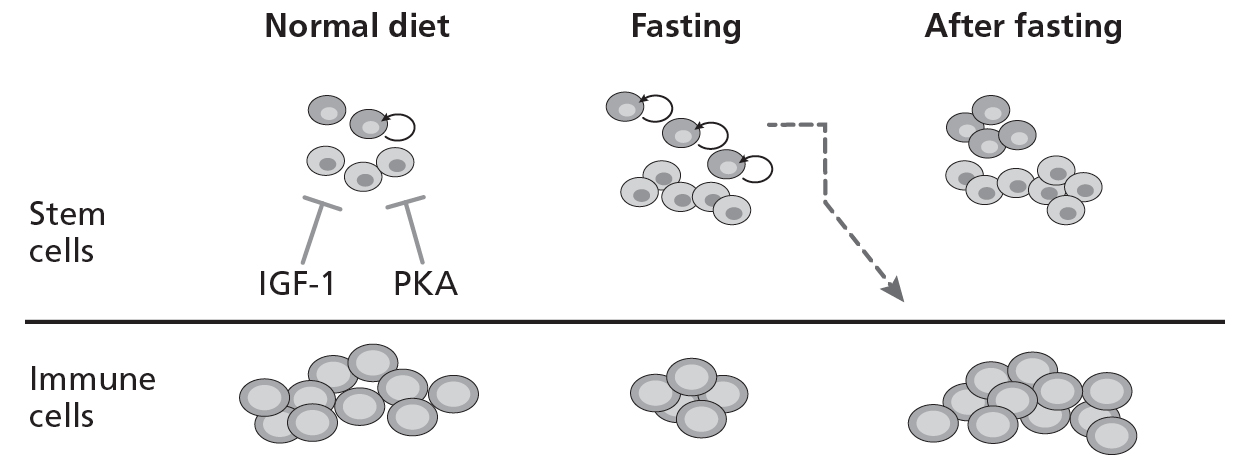

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is an autoimmune disorder in which immune cells (T cells) attack the insulating sheath around nerve fibers in the central nervous system. The clinical presentation includes debility of one or more limbs, partial or total loss of unilateral vision, and generalized pain. Patients generally suffer relapses of symptoms, which can be short but periodic. In some patients, the associated symptoms progress. Our research related to FMD and autoimmune diseases started after we discovered that fasting causes a major drop in the number of circulating white blood cells in mice, followed by a return to normal levels after they resume a normal diet (figure 11.1).10

11.1. Fasting cycles regenerates immune cells after chemotherapy

In the same study, we showed that during fasting, long-term hematopoietic stem cells are turned on and expanded. This type of stem cell, found in the blood, is capable of generating the various cells of the immune system. Two research questions followed this finding:

- Does the fasting preferentially kill dysfunctional cells, including autoimmune cells?

- When animals or humans return to their normal diet after fasting, will the stem cells generate only healthy immune cells or will the new cells also become autoimmune?

After we published our findings, I started receiving emails from people who, having read media accounts of our study, had attempted fasting to fight their autoimmune disorders. Several reported to me that four or five days of FMD had reduced and in some cases even cured their autoimmune diseases.

The results of our first set of tests in mice were remarkable. To replace autoimmune cells with good ones, we hypothesized, we had to first kill off the bad ones. It worked. Cycles of the FMD not only reduced the severity of the multiple sclerosis in all mice; it eliminated all symptoms in a portion of the mice that had already developed the disease. Each cycle of the FMD killed a portion of the autoimmune cells, and three cycles eliminated disease symptoms in 20 percent of the mice. FMD worked in another remarkable way: it promoted regeneration of the damaged myelin in the mouse spinal cord.

11.2. Rejuvenation from within

Thus, FMD cycles reversed the autoimmunity in a subset of mice by (1) killing off bad immune cells, (2) generating new and healthy ones, and (3) turning on progenitor cells (cells similar to stem cells), which can regenerate damaged nerves. This is an example of what I call “rejuvenation from within.” FMD kills many cells, but it is particularly effective in killing off old and damaged immune cells that have lost the ability to distinguish between the cells of its own body and invading organisms such as bacteria and viruses. Fasting increases stem cells but reduces immune cells. After re-feeding, stem cells generate new and healthy immune cells (fig. 11.2).

In mice, FMD could do even more: it seemed to prompt the body to detect damage in the spinal cord—like it detects damage to the skin after a cut—and turn on stem and progenitor cells to repair the damage. Could the FMD actually cure multiple sclerosis in human patients?

In collaboration with other researchers, we performed a randomized clinical trial on patients with multiple sclerosis (relapsing-remitting) to determine just this.11 Twenty MS patients were asked to undergo a single seven-day cycle of an FMD, followed by a Mediterranean diet for six months. The choice of the Mediterranean diet instead of the Longevity Diet was made by our clinical collaborators at Charité–University Medicine Berlin. In our future MS studies, we anticipate combining the periodic FMD with the everyday Longevity Diet. A control group of twenty MS patients continued their normal diet.

The FMD began with a pre-fasting day of 800 calories from fruit, rice, and/or potatoes. This was followed by seven fasting days, during which patients consumed 200 to 350 calories a day from vegetable broths or vegetable juice, supplemented with linseed oil (omega-3) three times daily. Patients were advised to drink 2 to 3 liters of unsweetened fluids each day (water and herbal teas). After the seven-day FMD period, solid foods were reintroduced slowly for three days. Patients followed a plant-based Mediterranean diet for the next six months (see chapter 4). An additional twenty MS patients were placed on a “ketogenic diet” (very high levels of fat, normal protein, and low carbohydrates) for six months; a ketogenic diet had previously shown improved outcomes for MS patients.

After the study ended, patients who had received a single cycle of FMD reported significant improvements in quality of life, physical health, and mental health. Side effects unrelated to MS were similar in both groups and were reported by approximately 20 percent of patients on the regular diet and those receiving the FMD. The most common side effects were respiratory tract infections and urinary tract infections, but there was no indication of liver or other damage. Ninety percent of the patients in the FMD group were able to complete the trial period. During the six-month study period, four relapses were observed in the control group, and three relapses were observed in the FMD group.

Overall, this study indicates that FMD is safe and potentially effective in MS patients, although additional and larger studies are necessary to confirm these results. Notably, whereas mice received multiple cycles of FMD, human subjects received only one seven-day cycle, which raises the possibility that efficacy would increase once multiple cycles are tested in human MS patients, followed by the Longevity Diet. We are now preparing to perform several larger clinical trials with hundreds of MS patients exposed to multiple cycles of FMD.

Crohn’s Disease and Colitis

After we published our work on fasting and immunity, journalist and autoimmune disease sufferer Jenni Russell of the Times of London wrote several articles about it. I include one of these articles below. At the time, it was too early to tell journalists about our work on multiple sclerosis and other autoimmune disorders, but we were already convinced the results were promising.

We have now carried out mouse studies on Crohn’s disease. The results are not yet published, but I can confirm they are very promising. Patients suffering from Crohn’s, colitis, or another gastrointestinal inflammatory disease should talk to their doctors about using an FMD in support of standard-of-care therapy. If the neurologist agrees, follow the FMD protocol in our multiple sclerosis article12 once every two months until either the symptoms improve or it becomes clear that the diet does not help. It is best if this is done as part of a clinical trial.

Rheumatoid Arthritis

Rheumatoid arthritis is a chronic autoimmune inflammatory disease resulting in the destruction of multiple joints. It affects about 1 percent of the overall population and 2 percent of people over the age of sixty. Fasting or very low-calorie diets lasting one to three weeks have been shown to be effective in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis, or RA. Inflammation and pain typical of RA can improve within a few days of commencing the fast,13 but they return after patients resume their normal diet. If the fasting period is followed by a vegetarian diet, some of the therapeutic effects remain.14 This combination therapy has produced beneficial results lasting years.15 The efficacy of this approach has been confirmed by four different studies, including two randomized clinical trials.16 For many patients able to endure long-term fasting and willing to permanently modify their diet, fasting cycles have the potential to not only augment but also replace existing medical treatments.17

What has yet to be tried is multiple/periodic cycles of the periodic FMD every one to three months in the treatment of RA instead of a single cycle followed by major changes in the diet. Our research on multiple sclerosis, Crohn’s, and several other autoimmune diseases—combined with our clinical results suggesting that FMD reduces systemic inflammation in the great majority of patients with high inflammation (CRP) at the beginning of the trial—suggests that the ideal way to treat RA will be with cycles of the five-day FMD (see chapter 6) every one to three months. Between cycles, I recommend the Longevity Diet described in chapter 4. We have evidence that monthly cycles of FMD could benefit RA patients even in the absence of switching to a Mediterranean or Longevity Diet. While this is not my recommendation, for those who cannot permanently change their diet, the monthly five days of FMD may be a good option. Notably, FMD would have the advantage of providing relatively high calories, which would allow patients to do this under medical supervision but without checking into a clinic. Considering that in our pilot multiple sclerosis trial a weeklong FMD was safe and potentially effective in improving patients’ quality of life, and considering past studies on RA, a periodic seven-day FMD may be more effective than a shorter one. After future studies, we will know more about the efficacy of FMD against various autoimmune disorders. We will also know more about the length and frequency of the diet best suited to treating these diseases.

Summary: Prevention and Treatment of Autoimmune Diseases

Prevention

- Follow the Longevity Diet, making sure you do so in such a way that you maintain a healthy weight and low abdominal circumference.

- Avoid a high-salt diet.

- Eat foods your ancestors ate frequently, and avoid foods that were not part of their diet.

Treatment

- Adopt all changes in the “Prevention” section above.

- With your doctor’s approval and close supervision, and preferably as part of a clinical trial, alternate the Longevity Diet with a monthly five-day FMD, or the seven-day FMD described above every two months.