two

EXCHANGING LEATHER SHOES FOR STRAW SANDALS

LIN ZHAO’S DEPARTURE FOR THE SOUTH JIANGSU JOURNALISM VOCATIONAL School left her parents exasperated, but it must have felt like a liberation from petty bourgeois self-interest for her, as she turned to the glorious task of building a socialist China. As a high school graduate, Lin Zhao was already considered a member of the class of intellectuals in a country in which 80 percent of the population was illiterate. The students’ assumption of an outsized public role for themselves was rooted in a Confucian tradition more than two thousand years old: “the scholar takes all under heaven as his responsibility” (shi yi tianxia wei jiren). The imperial civil service examination system channeled the aspirations of all scholars (shi) into government service and reinforced that sense of calling.1

The abolition of the imperial examination in 1905 had released the scholars from their presumptive role of governing, but the tradition did not die. During the 1910s–1920s, as a new generation of Chinese intellectuals turned their back on Confucianism in favor of Mr. Democracy (de xiansheng) and Mr. Science (sai xiansheng) from the West, they continued to view “all under heaven” as their exclusive responsibility.2 After the Communist victory, the door to becoming revolutionary shi was thrust wide open. In 1949, Lin Zhao was among more than a thousand young people who applied to the South Jiangsu Journalism Vocational School.

The school was located in Huishan, a picturesque suburb of Wuxi. It had emerged from an earlier party-run journalism school that opened in northern Jiangsu in 1946, one of the four training centers for propagandists that the CCP established during the civil war to help shape public opinion and win popular support.

Its prototype was the Resist-Japan Military and Political University—short-term training camps for military and government leaders, which the CCP had started in Yan’an and maintained throughout the war of resistance. Thousands of educated youths swarmed to these camps in the late 1930s, evidence of the success of the CCP in winning the educated over to its revolutionary cause.3

In 1949, Lin Zhao was 1 of 220 admitted. “I remember her pretty face, her elegant bearing, and her mandarin Chinese with notable Suzhou accent,” wrote Li Maozhang, who first met her in the fall of 1949. “She was talkative, witty and humorous, and often sharp and caustic,” Li added. She wore two French braids. “While chatting with others, she would untie each of the braids at the end… and braid them again, her head slightly tilted to one side, looking composed and carefree while chatting, laughing, and braiding.”4

The curriculum consisted of classes in news editing, management of news agencies, and telecommunications. No tuition was collected; room and board were provided free of charge, though conditions were spare. There was no classroom to speak of, or even a blackboard. Students either brought their own stools or sat on the ground; the teachers would cool themselves in summertime with a palm-leaf fan and a large pot of tea.5

Students were divided into classes, which were subdivided into study groups. Each study group, made up of nine or ten youths, shared a room: male and female roomed together, with only a mosquito net to divide the genders. “We lived in peace with one another with no troubles; there was no peach-colored news [sexual scandal] till we graduated,” a former student recalled. For all the hardships, their spirits were high. Out of Lin Zhao’s class, several eventually became nationally known journalists and writers.6

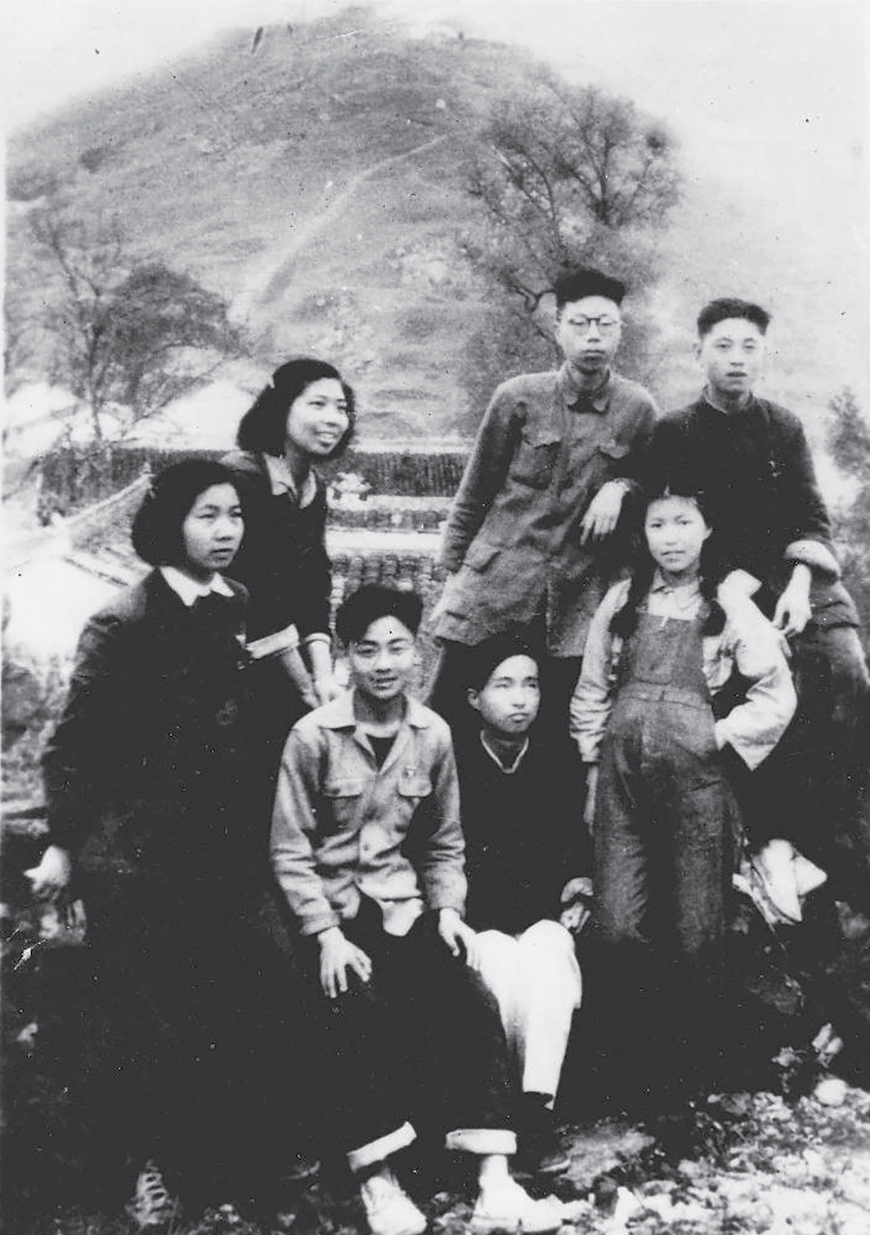

Lin Zhao, front row, first from right, with South Jiangsu Journalism Vocational School classmates, 1950. Courtesy of Ni Jingxiong.

At Huishan, students were trained to become both reporters and fomenters of the revolution. In ten months, they would complete their education and be assigned by the party to the frontline of the propaganda war. Meanwhile, during the fall term, three months were spent in rural areas, where they lived with and learned from the peasants, working hard to obtain “a diploma from the ‘University of the Peasants,’” as Lin Zhao put it, echoing a popular phrase of the time.7

Lin Zhao’s reporting on her class’s preparation for the journalistic stint in rural areas was an exercise in revolutionary piety. Entitled “A Few Days before Going Down to the Countryside,” it was her first published piece as a journalist. She wrote of the students’ mix of excitement and trepidation, and noted that some students had questioned the school’s decision, wondering if it was a good idea for them to interrupt their studies and go down to the countryside.

“Let’s just obey the [party] organization in all matters,” Lin Zhao urged. “The organization is always thoughtful and thorough in its considerations.” The most practical issue was backpacks and straw sandals. “It is said that those feet that are unaccustomed to straw sandals will have blisters when the skin is rubbed off,” she observed. “Going down to the countryside—this is quite a practical test. Don’t fail the test!” she exhorted.8

It was genuine piety, matched by a revolutionary humility. “We may make fools of ourselves and run into difficulties, but we are not afraid! We are going to live with the many suffering peasants and get to understand their thoughts and feelings; we are going to learn… many things that neither schools nor books can teach. We are going to cut off the last remaining section of the tail in our body.”9

That strange metaphor required no explanation. The coinage was Mao’s, in his characteristically earthy style. The tail to be amputated was the three isms: subjectivism, dogmatism, and sectarianism.

On March 9, 1942, the party newspaper Liberation Daily had published an editorial, drafted by Mao’s secretary Hu Qiaomu and revised by Mao himself, under the title “Dogmatism and Pants.” It rebuked the learned, often Russian-trained Marxists within the CCP—whose theoretical sophistication irked the irregularly educated Mao—telling them to “take off the pants” because “the problem lies in their lower, honorable bodies.” Since “a tail lies hidden under the pants, you have to take them off to see it.” Only then can one cut the tail of dogmatism off “with a knife.”10

Beginning with the Yan’an Rectification Campaign of 1942–1945, “taking off the pants” for the purpose of exposing the tail of unrectified thinking meant self-scrutiny of the most unforgiving kind. All those in Yan’an were required to keep “soul-searching notes” (fanxing biji) to lay bare their thoughts and renounce their former selves. A special party committee enjoyed “the right to demand to read the notes of every comrade with no prior notice.” Mao made it clear that keeping those notes for the party’s examination was mandatory. It was the party’s iron discipline, “more formidable and harder than the golden headband” of the Monkey King.11

Just as the magical headband had subdued the mischievous Monkey King, the protagonist in the classic mythological novel Journey to the West, Mao demanded that every follower of the CCP revolution yield to party discipline. “The cruel method of psychological coercion that Mao calls moral purification has created a stifling atmosphere inside the party,” noted a Comintern representative in Yan’an. “A not negligible number of party activists in the region have committed suicide, have fled, or have become psychotic.”12

By 1945 the disciplinary requirement to figuratively undress had resulted in a new clause in the new party constitution, which was passed at the Seventh Party Congress held that year. Now, CCP members were required to use the method of “criticism and self-criticism to constantly examine the mistakes and shortcomings in one’s own work.”13 It was to be done in public, and the party was the final arbitrator regarding the adequacy and the consequences of self-criticism.

AT JOURNALISM SCHOOL, Lin Zhao, like her fellow students, surrendered to the party by exposing her hidden failings. She had initially resisted public “examination of thoughts” and was prepared to go only as far as “pouring out my inner thoughts to two or three bosom friends on a night of cool breeze and bright moon.” Things changed after her class went to the countryside. In mid-October, her team held a week of intense self-study, and she overcame her own resistance.

It was strange that, after that examination, I felt a special ease in my heart. My burden of thoughts had been laid down; I was released from vexations.… When I did my examination, I felt excited; I also felt happy.… I now understand that, to release myself from my own thought burden… the only way is to completely bare myself, and accept the criticisms of my comrades. Only this way can I attain to the goal of self-reform and make myself walk the path of a new life.14

Lin Zhao had become a true believer. As a convert she had been given a new life in a noble, collective body, and the revolution had both evoked and satisfied her passion for self-renunciation.15

For Lin Zhao, as for other members of the educated class in the Communist ranks, the loss of individual autonomy was perhaps inevitable. Since their heyday during the May Fourth era of the 1910s–1920s, when intellectuals were the embodiment of enlightenment and the hope for national salvation, their influence had been on a steady decline. During the Northern Expedition of 1926–1927, Communist propaganda teams had galvanized the masses in the countryside with the slogan “Down with the intellectual class” (dadao zhishi jieji).16

Under the “revolutionary dispensation” of the CCP, intellectuals were seen as useful collaborators in the great undertaking of the creation of a new society. Like skilled artisans, they were deprived of the “authority of design,” and in fact their very selfhood. In the face of national emergencies—the Japanese invasion and the civil war—it became even more imperative for intellectuals to identify with national salvation. Mao had also reminded the party in 1927 that “political power grows out of the barrel of a gun.” It was guns, not learning or reason, that would establish the new political order in China.17

Over the years, the party had successfully mobilized the distrust and hostility of commoners toward the educated elite. Guilt-ridden about their own privileges, the intellectuals had, in response, found emotional release in self-abasement before the people and the party that claimed to represent them. Since the Yan’an Rectification Campaign, the revolutionary rite of passage for intellectuals was to descend into the pit of remorse, confess their sins against the party, bury the old self, and emerge into a new life as a “new person.” These new selves would renounce their former bourgeois class—along with its lifestyle, manners, and literary and artistic taste.18

In most cases, the conviction of one’s ineffectual old self was accompanied by a yearning to attain to the high ideals that the party represented. Many intellectuals began mimicking revolutionary writers.

Months into her training at journalism school, Lin Zhao had come to repudiate her former literary practice—her writings about herself, her emotions and dreams, in her “narrow circle of life.” Those writings had been “exquisitely decorated, filled with bourgeois sentiments, singing praises to ‘the smiles of life’ and ‘the new life of the good earth.’” It was only after she “entered the revolutionary school” that she began to understand that “literature must be popularized.” Her reading of progressive writers such as Zhao Shuli helped her understand the spirit of literature for the masses.

She also broke with her earlier reliance on inspiration for writing and saw the need for writing on demand. “As Comrade Qiaomu put it,” she wrote, quoting Mao’s secretary, “we need to train ourselves to master the skill of completing a news report in ten minutes.” And she overcame her former distrust of collective writing, for in it “I see the wisdom of the masses and the strength of the collective.”19

Lin Zhao’s conversion to revolutionary prose resulted in a series of saccharine journalistic pieces, which she produced with diligent zeal. She sang the praises of her revolutionary school as a “big, warm family,” where comrades cared for one another like brothers and sisters. She also wrote of the voluntarism of her fellow students who, while in the countryside, dropped their books and rushed to help unload a boatload of firewood and who picked up stray pieces of kindling to make sure that they did not “lose any revolutionary property.”20

She later wrote a poem dedicated to the year 1950, celebrating the reduction of land rent for the peasants in spring and the harvest and land reform—the overthrow of the landlords and the return of land to the poor—in autumn: “One cannot sing of all the grace and favor of the Communist Party that is higher than the sky and deeper than the earth.” After the outbreak of the Korean War that same year, in which China deployed a “volunteer army” of more than 1.3 million to “resist America, aid Korea,” Lin Zhao would also produce a glowing report about a young girl who embroidered a giant red star and the characters “It is glorious to join the army” on a satchel she had given her beloved, urging him to be a hero in the war.21

THE FORMULAS OF revolutionary writing dated to the late 1920s and early 1930s. In March 1930, with increasing numbers of Communist intellectuals seeking haven in the International Settlement in Shanghai, the CCP orchestrated the formation of the League of Left-Wing Writers in Shanghai, which drew together both dedicated Communist writers and other leftist intellectuals such as Lu Xun and Ding Ling. At a time when the significance of individuals paled in comparison to that of national salvation, literature must be a “fighting tool,” as CCP leader Qu Qiubai put it. It must advance the cause of revolution.

Ding Ling’s short story “One Certain Night,” written in 1931, served as an example: more than two dozen revolutionary prisoners, who had been chained together and marched through snow and sleet to an execution site, burst into singing “The Internationale,” the de facto anthem of the global Communist movement, as a machine gun opened fire. As they sang, “darkness fled. Appearing before them was an expanse of radiant light, the establishment of a new country.”22

The production of revolutionary literature expanded in Yan’an, where, in 1938, Mao Zedong approved the establishment of the Lu Xun Academy of Arts and Literature. Lu Xun had died in 1936, so the CCP had a free hand in appropriating his legacy of “cold ridicule and burning satire,” saving them only for the ills under the old society, from which the Communist revolution promised a complete deliverance. Hundreds of revolutionary writers, poets, playwrights, artists, and musicians were trained at the academy. Some went on to create monumental works of revolutionary art such as the opera The White-Haired Girl, in which a peasant girl, oppressed and raped by the evil landlord, flees to the mountain caves. Years later, her hair turns all white, and she is reduced to a ghost-like being, until the Communists come and emancipate her.

The boundaries for writers and artists were set by Mao’s addresses at the Yan’an Forum on Literature and Art in May 1942. Literature and art must serve the masses—workers, peasants, and revolutionary soldiers—and must be “led by the proletariat,” Mao said. Those who chose individualism took “the stand of the petty bourgeoisie” and would be “nothing but a phony writer.” Revolutionary writers and artists “must go among the masses,” to the “only source, the broadest and richest source, in order to observe, experience, study and analyze… all the vivid patterns of life and struggle.”23

IN LIN ZHAO’S case, close identification with the poor peasants did reveal to her a world she had not known before. Her time in the countryside gave her writing a new earthiness, evident in a narrative poem she coauthored after witnessing a “recounting bitterness” meeting. Entitled “Wearing Out My Eyes with Expecting—Records of a Peasant’s Indictment,” it was in the voice of an ill-treated, long-suffering peasant in the old society:

On someone else’s soil I trod; over my head was someone else’s sky,

I labored in someone else’s fields and thirty years went by.

……

Not a single grain was left each year for the next,

My back hurt; my tendons ached; my bones were dry.

……

My two crumbling rooms were like a pigsty,

Not big enough for a cow to turn to the side.

When his son contracts typhoid, the peasant has to borrow rice from his landlord at a ruinous interest rate to pay for the treatment. He is then forced to send his son to serve as a long-term laborer at the landlord’s house, as payment of his debt. The toil cripples the young man’s health; he collapses in the fields, coughs up blood, and breathes his last.

Without its wings a bird cannot fly;

All is in vain for a peasant without his land to live by.

……

Even the clay tiles on the roof would be turned over after a while,

I have waited until this day, wearing out my eyes.

……

Thirty years of bitterness, I have now got to its bottom,

Chairman Mao’s grace is higher than the sky.24

Lin Zhao felt a fire burning in her heart as she penned writings like this. “Each day that I am alive, I will not cease to serve the cause of people’s literature,” she wrote in a letter to Ni Jingxiong, her closest friend from journalism school. She wanted her writing to “benefit the people’s cause of liberation,” not to bring herself “fame and profit. How insignificant are they compared to our cause as a whole!”25

Only a few years earlier, when she was fifteen, Lin Zhao had written a potent, if sentimental, piece called “Tears at Dusk.” In it she had explored, with sensibility and subtlety, her self-doubts, despair, and the mysterious power of religion to offer solace.26 Gone now was the voice of a searching, lonely individual, replaced by revolutionary buoyancy.

WHILE IN THE countryside in 1949, living among peasants, Lin Zhao felt that she was shedding her former self—the “spoiled, willful” girl who had been easily offended and quick to anger. Her guilt over her own bourgeois family origins made the scarcity of rural life feel like a welcome penance. Even when she grew tired of the monotonous diet of plain rice mixed with unflavored vegetables, “seeing the ordinary people living on corn and pumpkin all the time, I feel that it is better for me to live like this,” she wrote her middle school friend Lu Zhenhua, “because I feel peace inside my heart; I no longer feel guilty toward the people.”27

And she came to admire the virtue of the masses, in life as in art. At a gala celebrating the Mid-Autumn Festival, with hundreds of local people in attendance, the peasants’ association presented a skit called “Liberation,” which they created, directed, and acted in themselves. According to Lin Zhao, the peasants—playing the landlord, the usurer, and the head of the village’s mutual-responsibility group—were “vivid in their laughs, their fury, and their curses.” Since the dialogue was in the local dialect, she found the satire more nuanced. “When they played the peasants, there was nothing of the feigned and strained acting that we arrogant intellectuals get into when we play the peasants,” she wrote. “That skit made me understand the boundless wisdom and creativity of the masses. The masses are the real geniuses. And I came to understand more fully what it means to go ‘from the masses, to the masses.’”28

The quoted words were Mao’s. “In all the practical work of our party, all correct leadership is necessarily ‘from the masses, to the masses,’” Mao had written in a directive to the Central Committee of the CCP in June 1943.29 Lin Zhao’s conviction of its truth was apparently heartfelt: she was writing to her friend Lu Zhenhua, who was working at the Suzhou branch of the Communist Youth League.

Beneath her revolutionary piety was the unabated shame of having lost her party membership. In fact, she was keeping a distance from Lu Zhenhua, a party member, and from all her progressive friends in Suzhou. As one who had previously “dropped out of the ranks” of the party, she was tormented by a sense of inferiority, she admitted to Lu. “It feels a bit like being too ashamed to see the elders on the east side of the river,” a reference to the predicament of Xiang Yu, a mighty third-century BCE warrior whose forces destroyed the Qin dynasty but who lost his bid for the throne to commoner Liu Bang and chose to take his own life rather than return to his village.30

For his part, Lu was in love with her. He asked to come to see her, but she made it clear that they would only be comrades and refused him. “Whoever wants to date me, I shall feel sorry for his misfortune,” she wrote Lu. “I have a heart of stone; he would most likely just be courting vexations. Moreover, in these circumstances, I tend not to take responsibility for somebody else’s vexations.” She did ask him to check on her family, to see if they had been placed under “penal control” (guanzhi) as enemies of the revolution. Guanzhi usually entailed restrictions on personal movement, loss of political rights, and at times forced menial labor.31

Lin Zhao’s relations with her parents remained fraught. As a seventeen-year-old, she still missed home from time to time, but her shame as a tainted revolutionary was enough to stiffen her toward them.32 She had often clashed with her parents when she was still living with them, she told Lu. “You know I have always had a rebellious spirit. Now that we live in a postliberation era, would I make the mistake of compromise, surrender to them, and lose my stand?”

Yet, breaking her earlier vow to completely sever ties with her family, she wrote to her parents in early October, three months after she left home, admitting to some mistakes when she renounced them. For some time, there was no response. “I don’t quite care,” she told Lu. “There is an unbending temperament in me.… One lives on after leaving family. In the meantime, I am indifferent to their financial support.” As a journalism school student, she received some monthly stipends, “and I earn some royalties for my writing,” she added. “Do you think I lack determination?”33

Maybe she did. Within months of leaving home, she traveled back to Suzhou twice. On the second occasion, she stayed briefly with her parents. However, relations remained lukewarm. Her parents were unresponsive to her exhortations to join the revolution, and she continued to worry about their “attitude toward the government.” Her father Peng Guoyan had lost his job after the Communist takeover. He would have chosen to leave mainland China for Taiwan had not his wife—the center of a “matriarchal family” as Lin Zhao quipped at one point—vetoed the plan.34

After 1949, Peng refused to “bow down his head and admit guilt” for his work for the Guomindang, insisting that there had been good people in the Nationalist government, that the Guomindang had done good things, and that, anyway, few people even had the opportunity to work for the Communists rather than the Nationalists before 1949. Early on under the new Communist regime, he often secretly listened to Voice of America, whose broadcast to China had started in the early 1940s. It was an act of “surreptitiously listening to enemy broadcast,” which Lin Zhao allegedly found out and reported to the government. In 1955, he was labeled a “historical counterrevolutionary.”35

Lin Zhao’s mother, Xu Xianmin, who had cofounded a bus company in Suzhou in the late 1940s, continued to serve as associate manager and deputy chair of the board of trustees of the company after 1949—remaining, in her daughter’s eyes, a member of the exploiting class. “I so much want to win over my mother, but I can’t help it: my heart is willing but my strength is weak. I can only sigh when I see other people’s parents becoming progressive.”36

Xu came to visit Lin Zhao at school a few times, bringing her money and supplies. Lin Zhao accepted the gifts with little visible excitement. She was more heartened by the political awakening of her twelve-year-old sister Lingfan, a student at Laura Haygood, who “has more or less come under my influence; she is progressive, and has learned to tell the difference between ‘the good’ and ‘the bad’ in other people from a political point of view.”

Still, the danger of bourgeois influence lurked in the family. “If my sister stays home all the time, she will be corrupted—she will be brought up as lady material.” Her most difficult relationship was with her father. “My father hates me to the bone; we have not corresponded for a long while,” she wrote in April 1950.37

IN MAY 1950, after three months in the countryside, a few journalism courses, and multiple group sessions devoted to thought examination and the study of government policies, Lin Zhao’s class graduated from the South Jiangsu Journalism Vocational School. The year had given her high spirits. “Life at the journalism school is full of vivacity and joy,” she wrote to Lu Zhenhua. “It is youthful.” At the graduation ceremony, a congratulatory banner given by Wuxi county’s party committee read: “Speak for the people; do propaganda for land reform!”38

According to her friend Ni Jingxiong, Lin Zhao was a prominent student at the journalism school. She had published some of her reporting, was known for being outspoken, and enjoyed public debate and the limelight. At graduation, the local Federation of Literary and Art Circles expressed interest in recruiting her.39

Instead, she volunteered to go to the countryside and experience the rural revolution firsthand. “I have no desire to become a phony writer,” she told Ni, echoing a phrase that both Lu Xun and Mao had used. She wanted instead to “participate in land reform, so as to forge and reform myself.” Her spirits were robust, even though her health was not. “Occasionally I run a low fever, but as long as I am not sick in bed, I don’t count myself sick.” It may have been the beginning of tuberculosis, but she did not see a doctor. That would have been a sign of petty bourgeois softness.40

Lin Zhao left Huishan in May to join a work team under the Suzhou Rural Work Corps. Over the next year and a half, she would help conduct land reform in four different areas in Jiangsu province. In September 1949, the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference had passed the “Common Program”—a proto-constitution set of policy guidelines—which outlined an ambitious plan for rural reform through rent reduction and land redistribution. In line with the practices that had been established in Communist-controlled areas during the 1940s, the land reform program was coordinated at the local level by work teams with the assistance of hastily organized peasant associations.

In June, she wrote to Lu Zhenhua, asking him to help her purchase a color portrait print of Chairman Mao from the New China Bookstore in Suzhou. “I fell in love with it the last time I was in Suzhou, but they ran out of stock,” she explained. “Since I came to the countryside, my spirits have never been low.… By the middle of this month, my term as a provisional Youth League member will expire. After I become a regular, I will try even harder to be a good Youth League member. I am not burdened with any worries now. Very happy. Full of energy in whatever I do.”41 At the time, membership in the league was a stepping-stone toward party membership.

The CCP’s rural reform expanded across China in the second half of 1950. In most cases, the work teams, with help from peasant associations, would identify and isolate landlords and set up violent confrontations—denunciation meetings—at which tenant farmers were encouraged to seek vigilante justice. In July 1950, the Government Administrative Council (later renamed State Council) had authorized the formation of “people’s tribunals,” made up of local activists, against “local tyrants,” bandits, and others opposed to land reform. As rural reform got under way, between one and two million people were killed. Several million more were placed under penal control, extra-legal punishments that varied in severity.42

In one township selected for a model land reform program, Lin Zhao and her teammates were each put in charge of one hamlet with more than a hundred households. It was difficult work. “I was fearful at first,” she told Lu in October, but had found a magic weapon, which was to “consult with the masses” instead of dictating to them. Three months later, she wrote from another “backward” village, where land had been redistributed and the grains requisitions quota was nearly met. She told Lu that “the work is very dangerous,” and she was afraid she might not be able to complete it in time.43

The danger she faced stemmed from covert resistance to land redistribution and grains requisitions. Across China, more than three thousand work team members on requisitions assignments had been killed in rural areas in the first year after the Communist takeover. The big landlords, who typically lived in the cities, often tried to hide their landholdings and wealth. Others resorted to more nefarious measures. Ni Jingxiong, Lin Zhao’s journalism school friend and a fellow member of the Suzhou Rural Work Corps, was assigned to a work team in the Lake Tai area. She was warned not to venture out at night, lest she be “plopped into Lake Tai like a wonton,” as others had been.44

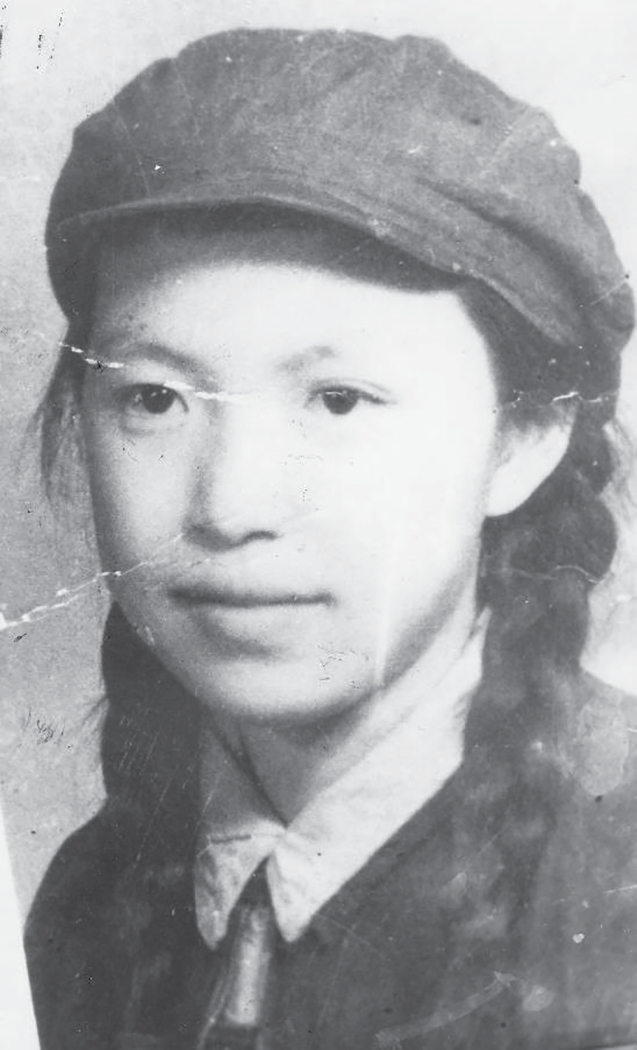

Lin Zhao, March 1951, as a member of Suzhou Rural Work Corps land reform team. Courtesy of Ni Jingxiong.

Lin Zhao worked feverishly during the day, and spent most of the evenings writing. “I often stayed up until after 11 p.m., sometimes after 1 a.m.” One of the works she completed during this period was a play in the Suzhou dialect, which was well received when it was staged in the countryside. It featured a peasant wife—played by Ni Jingxiong—as protagonist, who exhibited exemplary revolutionary consciousness: she urged her husband to make a prodigious self-sacrifice in contributing “public grains.”45

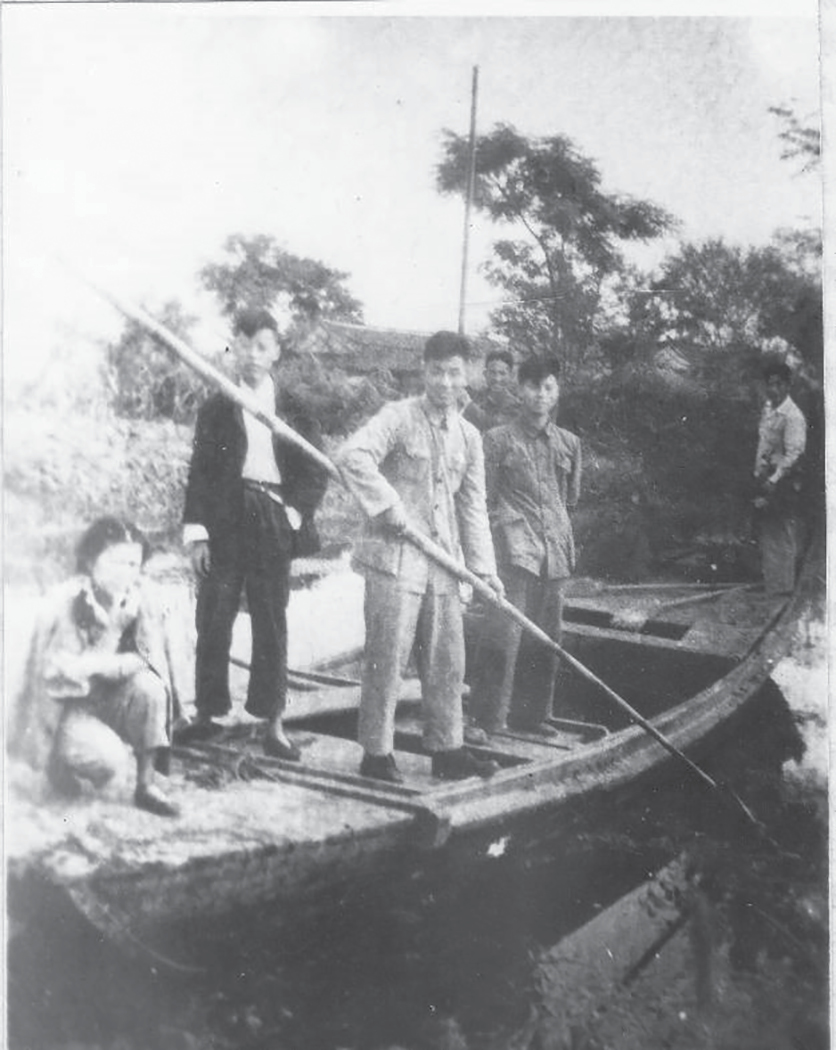

Lin Zhao, first from left, with fellow members of Suzhou Rural Work Corps land reform team, 1951. Courtesy of Ni Jingxiong.

Lin Zhao as a member of Suzhou Rural Work Corps land reform team, 1951. Courtesy of Ni Jingxiong.

Lin Zhao, front row, second from right, with fellow members of Suzhou Rural Work Corps land reform team, 1951. Courtesy of Ni Jingxiong.

By early 1951, Lin Zhao was coughing constantly and often running a fever. “Even if I become really sick,” she told Ni, “I will work till the last moment. Maybe I will live a shorter life than others, but if my life is fully utilized, I shall have no regret dying young.” In March, an X-ray revealed stage 1 tuberculosis, and her work team leader advised her to rest, but she insisted that she had to stay at her post until land reform in the area was completed. “After all, it is not fun to lie in a sickbed in this spring of life.”46

Over the first two years of Communist rule, the mass campaign of rural reform remade the countryside. It also remade Lin Zhao. “The mass movement has a huge tempering effect on people,” she told Lu Zhenhua, and added that, for her, it marked only the beginning of her own thought reform.47

That required a renunciation of her upbringing. Throughout her childhood, her father Peng Guoyan had worked to pass on his own classical learning to her, especially in early Chinese literature. He had wanted to rear her as a boy, to see her develop into a scholar in the traditional vein—learned, independent, proud, disdainful of the vulgarity of the worldly, and upholding Confucian values of loyalty, propriety, and personal integrity. To him, these qualities embodied the upright spirit of the Chinese people, which could be traced to the Yellow Emperor.48

Yet the spirit that her father had instilled in her and the values she had been taught at Laura Haygood began to dissipate as she threw herself into revolutionary work in the countryside. Her job required a proletarian tough-mindedness she had not possessed before—a disregard for civility and a contempt for the claims or the pain of individuals if they stood in the way of the righteous cause of making a new society.

When Lin Zhao first went to the countryside in 1949 after the autumn harvest—for the three-month stint in a rural area as part of her journalistic training—her team had been asked to help with the government’s grains requisitions. At the time, some fellow students had expressed misgivings about demanding grains from the peasants, but Lin Zhao insisted on following the party’s dictates. She told one group of peasants that the government was their own and that “what is taken from the people is used for the people.” It was for the villagers to sort out how much the extremely poor would have to contribute, but the village collectively had to meet its requisitions quota. “We are not devouring or wasting people’s blood and sweat; we are here for the long-term benefits of all the people,” she assured them.49

Now as a land reform work team member, she found herself facing the landlords themselves. The encounters were tense. In the township of Chengxiang in Taicang county, more than 100,000 kilograms of rice were forced out of the nearly three hundred landlords, “but the masses are still unsatisfied; they said that the strike [against the landlords] was still inadequate,” Lin Zhao reported. The screw had to be tightened even more.50

“I recalled that, at the first struggle meeting, I felt pity for the landlord and thought the peasants were rough.” But, a year into her work, she had forged a new toughness in herself. She now insisted that requisitions had to proceed as directed by the government. “Not a single grain may be withheld!” she wrote to Lu Zhenhua in May 1951. “When I see the wretched, pitiable state of a landlord, I feel only a cruel satisfaction inside.”

Lin Zhao’s baptism into revolutionary violence had just occurred that same month when she helped prepare a ritual sacrifice to celebrate International Workers’ Day (May 1), a major holiday in the CCP’s liturgical calendar:

To mark “May 1,” more than a dozen people were executed in our township. One of them was a collaborator [during the Japanese occupation] and an evil tyrant landlord from the neighborhood where I am in charge. From the collection of materials and the organization of denunciations all the way to the public trial, I did my part to send him to his end. After they were shot, some people did not dare to look, but I did. I looked at the executed enemies one by one, especially that evil tyrant. Seeing that they had perished this way, I felt the same pride and elation as those who had been directly victimized by them.51

These were orthodox class feelings, long sanctified by Mao. In 1927, after spending a month in five counties of Hunan province, Mao penned “The Report on an Investigation of the Peasant Movement in Hunan,” which he lauded as terrific.

It was true, Mao wrote, that local peasant associations had taken matters into their own hands, exacting fines and contributions from local tyrants and evil gentry and “smashing their sedan chairs.” Crowds of what some called riffraff had swarmed into the houses of local gentry to “slaughter their pigs and consume their grains. They even loll for a minute or two on the ivory-inlaid beds belonging to the young ladies in the households of the local tyrants and evil gentry. At the slightest provocation they make arrests, crown the arrested with tall paper hats, and parade them through the villages.… Doing whatever they like and turning everything upside down, they have created a kind of terror in the countryside.”

There were also executions of landlords ordered by special tribunals formed by peasants. Those seeming excesses, Mao wrote, “were in fact the very things the revolution required.” For “a revolution is not a dinner party, or writing an essay, or painting a picture, or doing embroidery; it cannot be so refined, so leisurely and gentle, so temperate, kind, courteous, restrained and magnanimous. A revolution is an insurrection, an act of violence by which one class overthrows another.”52

Mao’s glorification of the violent justice meted out by the Hunan peasants set the tone for later CCP policies as it worked to remake the social and economic order in rural China. Many years later, in an essay written in her own blood while she was behind bars, Lin Zhao would reflect on Mao’s report on the Hunan peasant movement, which provided the blueprint for the land reform campaign she joined in 1950 and which made revolutionary contempt for the life and property of the landlords imperative:

“The Report on an Investigation of the Peasant Movement in Hunan” blatantly promotes and grandly extols savage methods of personal insults directed at individuals—dragging people out to be paraded through the streets, putting tall paper hats on them! So on and so forth. The purely spontaneous, plain acts of revenge on the part of the peasants are one thing. At least that is understandable! But when it becomes a component of “Mao Zedong Thought” and is used in a general manner against anyone who refuses to yield to them and anyone whom they want to strike against… it’s blood! Blood! Blood!53

In May 1951, when Lin Zhao surveyed the bloodied bodies of the “class enemies,” she was likely conscious of the writer Lu Xun’s comments on Chinese onlookers at executions. She began reading Lu Xun before 1949 and had often felt his “burning love and hate between the lines.” It is a well-known story that, while studying at a medical school in Japan in 1905, Lu Xun had watched a lantern slide show in which a Chinese was being beheaded by Japanese soldiers while other Chinese looked on. There was numbness written on their faces.54

That image changed Lu Xun’s ambitions in life. Instead of training to be a doctor who would save lives, he would become a writer who could save souls. In “Medicine,” a short story he published in 1919, the reader is introduced to a group of onlookers at a nighttime execution, “all craning their necks, as if those were the necks of ducks grabbed by invisible hands and pulled upwards.”55

Yet Lin Zhao was not craning her neck in soul-less, blank apathy. On the contrary, intense feelings drew her to the bodies of landlords and counterrevolutionaries that had been lacerated by bullets. “Stored in the depth of my heart is a burning love for the motherland, as well as an equal amount of hatred for the enemies,” she wrote Ni Jingxiong.56

By that time, her land reform work had undone much of her genteel upbringing, but the violence of those days would haunt her years later when she found herself in prison as an enemy of the people. The realization that she had been “more or less splashed with blood” during the land reform period would bring her “shock and deep grief.”57

LAND REFORM WORK also eroded Lin Zhao’s religious loyalties. In the township of Bali in Taicang county, Lin Zhao’s work team encountered an obstacle different from that of the landlords. “There were many Catholics in the area, so it was very hard to mobilize the masses,” recalled Li Maozhang, who was on the same work team as Lin Zhao.

In spring 1951, land reform in Bali had turned to identifying class enemies. In the CCP’s view of the world, the clergy were members of the exploiting class, to be isolated from the masses and ostracized, not unlike the landlords. However, dislodging the local priest proved difficult. Lin Zhao’s work team was also frustrated that the congregational life of the Catholics made it hard for them to rouse the peasants, so they set up their base in the village’s Catholic church, having invited themselves in. As Li Maozhang recalled,

the moment the priest came, all the followers of the doctrine went to pay him respects, and served him the most delicious food they had. At worship, the church was filled with those followers.… One had to marvel at their piety.… They would listen to the priest, and would not listen to us. We were unable to hold the meetings that we wanted to have, and our work plan was in disarray.58

The work team decided to put the priest in his place and wake up his flock:

One day, that priest was again leading the full congregation in worship. Several comrades on our team who were from the army could not take it anymore. They took out their guns in the corridor outside the church, and, “bang, bang, bang,” fired into the air.… What was even more annoying was that, no matter how you fired your weapons, those believers would not budge a bit.59

After the worship ended, the priest calmly reminded the intruders that they had violated the Common Program, which guaranteed the freedom of religious belief.

At this, Lin Zhao spoke up. She acknowledged the clause on religious freedom in the Common Program but added that the CCP Central Committee had recently issued a new directive. It had ordered all religious activities to be suspended in areas where land reform was underway to allow the party’s work to be carried out smoothly. “Your religious activities have seriously hampered our land reform work,” she warned.

“There was a bit of shock effect in her reasoning,” Li Maozhang recalled. “It took the priest by surprise. He did not say a word. After a moment of hesitation, he walked off. We never saw him again until land reform ended.”60

By then, Lin Zhao’s hatreds and passions seemed perfectly aligned with the party’s dictates. “I feel a deep love for our work, a deep love for our peasant brethren who have stood up,” she wrote Lu Zhenhua in March 1951. “I hope that one day, I will be able to write to tell you: ‘I have once again returned to the ranks of the party.’” To her close friend Ni Jingxiong, Lin Zhao sent a cordial challenge: “Let’s strive to join the party while we are in the Rural Work Corps.… Let’s strive to join the party in 1951! My good comrade, give me your hand and accept my challenge!”61

RETURNING TO THE party turned out to be a more tortuous journey than she had imagined. Chief obstacles included her parents’ political background and her own ambivalence toward them. From the moment she entered the South Jiangsu Journalism Vocational School, she had been pressured to renounce her family. She had dutifully condemned her father’s inglorious past as a county magistrate as well as her mother’s term in the National Assembly during the Nationalist period, but when her entire work team held a meeting to discuss the “problem of Lin Zhao’s stand” and demanded in the name of the party that she draw a clear line with her family, she endured the criticisms with a long silence but in the end “burst into loud crying,” one cadre recalled. “I don’t understand, why do I have to sever ties with my family just to take a firm stand?” she protested.62

As she lamented in her diaries written in 1950, “I want to strive upward, but the vestiges of the old society, the deep-rooted evils of the petty bourgeoisie, are dragging my feet downward like a rock—when can I overcome them?” In another entry, she wrote, “The warm feelings about my family have taken hold of me; I want to go home.… I feel an escapist urge inside me. Go home! At least, I can have a few days of peace at home, and let the wound in my heart heal.”63

Lin Zhao had taken heart when, in 1951, her mother wrote a long letter to express support for her land reform work. “The Suppression of Counterrevolutionaries work in Suzhou has educated my mother,” Lin Zhao told Lu Zhenhua.64 This was a reference to the other mass campaign that Mao launched in 1950 to ferret out those who he believed posed a threat to the new regime—“bandits,” “spies,” leaders of “reactionary” religious societies, as well as former officials and army officers of the Nationalist government. About three-quarter million, and possibly as many as one million, were executed to meet the quotas set by Mao and the party’s Central Committee. “Mother has become our friend!” she exclaimed.

Not so in the eyes of her comrades in the Rural Work Corps, who finally brought her around to a politically sound view of the matter: “In the past I was quite sure that my parents were not counterrevolutionaries. I based that simply on the fact that they had not been arrested,” Lin Zhao reflected in a letter to Ni. The progressive tone in her mother’s recent letters had also misled her, she explained. “It was only with the help and illumination from the comrades in the Corps that I realized that, to have worked for the reactionaries and to have held positions that were not low, that in itself was a form of evil. It had absolutely no benefits for the people, and they must be treated as belonging to the class of counterrevolutionaries.” This revelation made her feel all the more inadequate. “I still fall far short of the party’s standards,” she admitted. “Especially for people like us, the old tail is too long.”65

The party’s voice had again prevailed. Since she joined the revolution, that voice had always been the dominant one, more forceful and righteous than her own. It had shamed and diminished her. She had yearned to own that voice to drown out her own petty bourgeois sentiments—her lingering attachment to family, her frequent attraction to men, her impatience with those comrades who extended to her a patronizing helping hand, and her irritation with uncouth suitors in the Rural Work Corps. There was also the nameless melancholy she had known since middle school days, which all the jubilation and euphoria of the revolution had not dispelled.66

She spoke hesitantly and with bewilderment in her diaries and her letters to Ni Jingxiong. They had developed a passionate friendship and kept up regular correspondence after joining the Suzhou Rural Work Corps in May 1950 and being assigned to different work teams. “My diaries are full of ‘inauspicious words,’” she wrote Ni. “It is as if the moment I start to write an entry, I cannot help but voice some discontent, and vent some backward sentiments. Nobody will know that; nobody will slap a big hat on me. So the diary has become a little world for my soul.”67

In her own little world—writing for herself or to Ni—she perceived the coldness of society; she felt wounded by her comrades’ incessant criticisms of her pride and of her “fragile feelings.” “I have only cried three times since the beginning of 1951,” she declared to Ni in April of that year.

Despite all this, Lin Zhao was not incapable of happiness. She had often found deep joy in the countryside “walking in the fields, looking up at the blue sky and at the soft clouds drifting by.” In springtime, “the sun shone gently; a breeze sent waves through the wheat fields.” As she asked Ni, “What reason do we have not to sing joyful songs to this beautiful life?”68

WHAT WEIGHED ON her most was “the single remaining issue” of her party membership, she told Ni. By April 1951, she feared that “the party has raised its requirements; the qualifications are now different.” And she began to despair of joining the party before the work of the Rural Work Corps was completed.69

In the event, it was not the CCP’s high standards that made regaining party membership an unattainable goal. Rather, it was her attempt to hold low-level officials to the party’s own standards. She had expected basic human decency from the CCP cadres who held power over her, and was woefully tactless in confronting their own failings.

One late night, she went to visit Ni Jingxiong. Instead of finding Ni, she saw the captain of Ni’s team reclining in a bed in the women’s quarters. Startled, he reprimanded Lin Zhao, asking why she had left her own team late at night. She shot back sarcastically that whatever she had done was not as bad as a man sneaking into the female dorm in the middle of the night. The next day the captain publicly accused her of seeking him out late at night to malign him.70

After the success of the Communist revolution, it was not uncommon for CCP cadres of country background—small heroes of the revolution—to court good-looking city girls who worked under them, divorcing their peasant wives when necessary. Among the cadres who did so was the commissar of Lin Zhao’s work team. He won over a woman under him by framing her boyfriend and purging him from the land reform team.71

Lin Zhao scorned this act as “taking away another’s woman with a drawn sword.” “Recently a double happiness has come to the commissar of my humble team,” she observed wryly to Ni in August 1951. “The first is that he has been selected to go to study at the cadres’ school,” which usually preceded a promotion. The second was that “he has decided to separate from his yellow-faced wife back in his home village and from his son, in order to marry the slender female comrade on my team who has some faint white freckles on her face—you are going to blame me for my frivolous and caustic remarks, but, for some reason, whenever I mention the cursed business of this sort of guy, no benevolence accumulates on my tongue.”72

Lin Zhao’s acid comments bespoke a deep wound of her own: earlier that year, a cadre on the work team, married and a dozen years or so her senior, had shown special “care” for her. She became romantically involved. Within a few short months he was reassigned to another leadership position elsewhere, and their relations ended. “In emotional matters, I have been taken advantage of quite a bit,” she confided to Ni. In a subsequent letter, she wrote, apparently referring to the same man, “somebody insulted my love, ruined my youth, and left a permanent scar on my emotions.”73

Ni at the time had already learned of Lin Zhao’s sexual encounter with the cadre. Furious and eager to protect Lin Zhao, she had confronted “that turtle’s egg… an incredibly officious man”—who quickly put her in her place. He made it known to her that she had made an undue fuss.74

Lin Zhao’s bitterness after the man left may help explain the sarcasm she trained on her own commissar. She would pay a dear price for it. The commissar secretly compiled damaging materials on her and sent them off to the region’s party leadership.75

On December 21, 1951, at the ceremony held by the Rural Work Corps on the outskirts of Wuxi to mark the conclusion of the land reform work, with about a thousand people in attendance, the head of the party’s organization department of the South Jiangsu District dropped a bomb: he did a tally of the people who had gained party membership as a result of their laudable efforts and of those who had joined the Communist Youth League during the same period. “However, there are also those who are incapable of being reformed, such as the famous Peng Lingzhao!” he pontificated, using Lin Zhao’s formal name. “Her thoughts and her conduct have always been vile.” He cited her drinking, evidence of her bourgeois liberalism and lifestyle. She had been found lying in a dirt footpath in the fields, he added, drunk as a lord, bringing shame to the work team. This kind of person “needs to find another place to be reformed.”76

Lin Zhao was known among her comrades to have weaknesses for meat and wine. Whenever she had a break from the austere life on the work team, she went to town to seek out a restaurant for a dish of her favorite lamb. She would sometimes borrow money and forget to return it. Once she invited Ni Jingxiong to “improve our diet” in Wuxi. Where was the money? Ni asked. “It’s here,” Lin Zhao said, waving in front of her the vest that her mother had just sent her for the winter. She sold the vest, and the two ate their way through local delicacy stalls.

At times Lin Zhao had also drunk a considerable amount of wine, despondent over her tainted political past, the unforgiving scrutiny of her thoughts, life, and family by the party, and her private woes. The public shaming of Lin Zhao was a calculated retaliation, which her commissar later admitted. She no longer had any hope of rejoining the party. “Have I really sunk to an unredeemable level?” she wondered in a letter to Ni. “Yes, I have let the party down, but I also suspect that somebody has let me down.”77

Years later, in her letter to the editorial board of People’s Daily, Lin Zhao would reflect on the years when she worked for the party. When she joined the revolution, the CCP cadres were “taking off straw sandals and changing into leather shoes; we took off our leather shoes and changed into straw sandals!” She went on:

Where did you not find us the young people, the nameless heroes whom many at the time scorned as “little crazies,” opening up virgin land and breaking new ground under the stars and the moon, with calluses growing on our hands and feet! Inspired (deluded!) by such noble ideas as “country,” “society,” “people,” these young people… each with “utter devotion to others without any thought of himself” cast the most precious time of their youth upon the soil! And it was precisely because tens of thousands of innocent, zealous youths eagerly shouldered the hardest and the most down-to-earth frontline work at the grassroots level that the Communist Party was able to make up for the serious shortage of political cadres, and this regime was able to effectively consolidate its power from the ground up!78

What Lin Zhao could not see when she gave her life to the revolution at the age of seventeen was that the CCP regime that hot-blooded youths like her helped to consolidate would serve the interest of the privileged “new class,” a term coined by Milovan Djilas, the former Yugoslav Communist leader who had “traveled the entire road of Communism.” As Djilas learned through hard experience, “membership in the Communist Party before the Revolution meant sacrifice. Being a professional revolutionary was one of the highest honors. Now that the party has consolidated its power, party membership means that one belongs to a privileged class. And at the core of the party are the all-powerful exploiters and masters.”79

Djilas had a warning for people like Lin Zhao, one she never had a chance to hear. She would have to find out its truth on her own. He wrote, “Revolutionaries who accepted the ideas and slogans of the revolution literally, naïvely believing in their materialization, are usually liquidated.”80