eight

BLOOD LETTERS HOME

Mama:

Do you remember this date? It’s the seventh anniversary of my arrest! That night seven years ago, when you saw me being handcuffed by them, you wept—even though you had not cried when you encountered the same moment of trial in your own fighting career.

Don’t grieve for me, dear Mama, a raging fire refines the true gold. After all, I am in the hands of the Heavenly Father, not in the hands of those demons!

I was very calm today. No superfluous sadness, because it is useless! From the day of my arrest I have declared in front of those Communists my identity as a resister; I have been open in my basic stand as a freedom fighter against communism and against tyranny.…

I have a chestful of brave thoughts as a fighter, but I don’t know when you will get to read even these few words. Maybe at an exhibition? Just for a laugh!

I want to see you! My Mama, I want to see you!

Your daughter Zhao,

October 24, 1967, the Lord’s calendar1

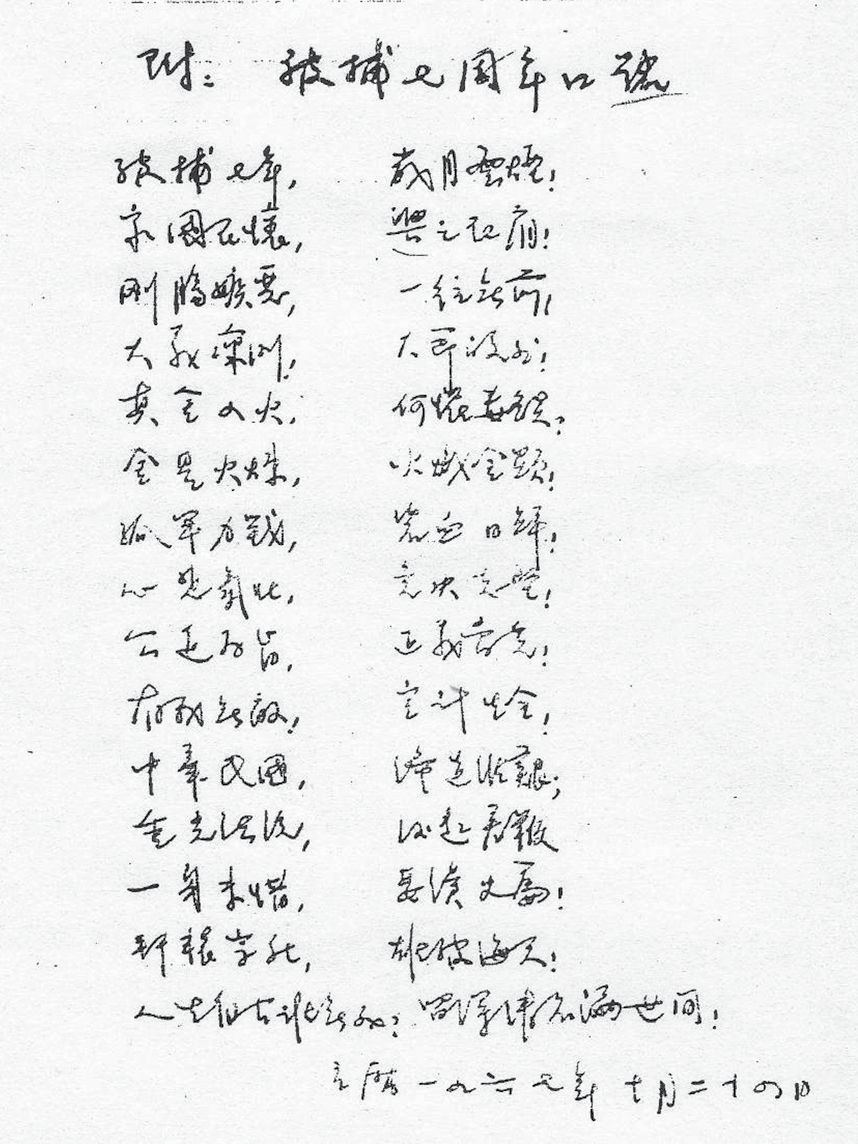

The letter was done in her own blood. On the same day Lin Zhao wrote this letter, she composed a poem that she called a lyric “slogan.” The opening lines read:

Lin Zhao, “Slogan Marking the Seventh Anniversary of My Arrest,” four-character rhyme, October 24, 1967.

Seven years have gone by since my arrest;

those years, like passing clouds, I have lost them all!

My country remains in my heart;

still a burden on my shoulder is its rise or fall!2

Lin Zhao had taken up blood writing again in early October 1967 as a protest against the suspension of family visits and in response to the “vile abuses.” For six weeks she had been denied water to wash her face or her clothes, and it had been almost six months since her last family visit in May. (On that occasion, her sister Peng Lingfan had arrived to see her, but much to Lin Zhao’s disappointment, her mother, who was in Suzhou, had not.)3

Her intermittent hunger strikes had not resulted in better conditions. “Instead, I have been granted special visits day after day by roughneck inmate housekeepers who bullied me.” Starting on October 14, she wrote out one blood-inked protest per day. She addressed them to the prison authorities and handed them to the guards along with her blood letters home, repeating the demand that she be allowed to see her family. Meanwhile, to her exasperation, inmate housekeepers repeatedly threw water on her from outside her cell.4

The denial of family visits was likely an attempt to break her spirit and subdue her, but Lin Zhao’s quibbling with the language the prison used on the prisoners’ visit cards did not help either. According to Tilanqiao’s rules, inmates could write monthly letters home around the middle of each month; they could also fill out and return visit cards at the same time to request visitation by family members the following month. The cards referred to an inmate as a “criminal.” Lin Zhao found the word offensive. “As everybody knows, I am determined to never ‘plead guilty’ and I refuse to yield to them! Therefore, whenever I see the word ‘criminal’ printed on the card, I instinctively detest it and cannot tolerate it,” Lin Zhao explained to Xu Xianmin.

Thus, each time a visit card was distributed, she either ignored it or blotted out the character “criminal” after she took the card. “We are inmates! Not the so-called ‘criminals’!” she told her mother. In September, she did not take the card when it was offered. The following month, the prison authorities withheld the card, and using her failure to fill out the card as an excuse, “they simply canceled the visit for me!”5

Helpless, Lin Zhao announced that she would start writing blood letters home until she was granted a family visit. On October 23, she set out on a month-long protest in the form of one blood letter home each day, consecutively numbered and each signed “Your daughter Zhao” and dated according to “the Lord’s calendar.” She collectively titled them “Blood Letters Home—to Mother.” After completing each letter, which she doubted the guards would send out, she copied it into a notebook, using a pen. For more than two weeks, she enclosed with every letter a statement entitled “Protest over the Current Condition,” which was also consecutively numbered and done in her own blood. Her letter of October 24, the anniversary of her arrest, was No. 2.6

No. 3 (October 25, 1967)

Dear Mama:

Every day I long to see you. Every day I am writing a letter to you in blood. At the same time, just about every day, I am showing them my protest in blood!…

I am not feeling well today: headache, nausea, and chills. It is gradually getting cold, but I haven’t yet stitched my quilt together because the cover sheet was taken away by them, and they won’t return it. Don’t you think that’s loathsome?! Alas, Mama, you don’t know how hard my battle is! But, relying on the truth and justice of the Heavenly Father, I have no fear! I wish you good health! My Mama!

No. 7 (October 29, 1967)

Mama, greetings!

It’s the Sabbath day today. I spent a good half day mending my clothes. Some of my clothes can already be used as denunciation material one day. … Still, here in prison I belong to the class of people who are clothed in prettier colors. To forget for a moment people inside the prison: occasionally I catch a glimpse of the street outside, and can see that, out on the street, none of the pedestrians is decently clothed! If it is like this in Shanghai, you can just imagine the situation elsewhere! It’s been eighteen years after all.… Alas! Mama! They have communized China into a country of beggars, and this is only the more visible part of the multitude of horrendous evils committed by this cursed gang of bandits! We would run out of ink writing about their “virtuous rule” even if we turn the ocean into ink!

When Lin Zhao started her blood-letter protest, she had demanded that a family visit be granted her before the end of October.7 On October 30, she sank into “an unusual bleakness and deep anger” but simultaneously felt a “frozen composure.”

She called to mind “Friar Bacon and the Brazen Head,” a story in James Baldwin’s Thirty More Famous Stories Retold, which she had read in the English original, probably while a student at Laura Haygood. Friar Bacon, an Oxford professor and a wizard of sorts, asks his servant Miles to watch a brazen, or bronze, head he had made and to wait for the moment when it might utter “a secret of the greatest importance to every Englishman.” Miles is scornful of the head and taunts it—until the moment when the brazen head, turning the metallic smile on its face into a frown, lifts itself from its marble pedestal and, in a thunderous voice, roars “TIME IS PAST!” With a dreadful crash, the head falls and shatters into a thousand pieces.8

“I thought of that imaginative and mysterious piece ‘The Brazen Head,” Lin Zhao told her mother in her October 30 letter, using its English title. “I thought of that sentence in the story: Time is past!” She added that she had quoted that line to the guards the previous year and “repeatedly warned them” that time was running out for the Communist regime to repent.9

On October 31, Lin Zhao wrote a “Declaration in Blood.” She began by announcing, in English, “The time is past!” Her demand for a family visit had again been rejected. Still, she vowed to remain loyal to the battle of “free humanity” to “resist the evil way of communism, to resist the totalitarian system, to resist the rule of secret agents, to defend human rights and freedom, and to establish democracy for the nation!”10

Before handing her writing to the guards, Lin Zhao read it aloud into the open space between the outside wall and the gangways so that those on the lower floors could also hear her. Similar to the Alcatraz Federal Penitentiary, the five tiers inside a Tilanqiao block shared a large open space, so that activities on all tiers could be monitored simultaneously. This allowed Lin Zhao to “publicize” her protest, as she told her mother in her blood letter the next day.

She also told her mother that, beginning on November 1, she would “write my Blood Letters Home in Protest in an orderly manner so that in the future they will form a separate volume in my collected works ‘Freedom Writings.’ I have given these letters the general title ‘To Mother.’”

Lin Zhao recalled that her family used to own a book entitled A Mother Fights Hitler. She had been deeply moved when she first read it “because I could not but estimate that, one day, I might encounter the same destiny as the lawyer [Hans] Litten! And that is to become an imprisoned one under the tyrannical rule!”11 Her own experience had borne out that premonition, but “compared to the tyrannical rule of the Chinese Communists, Hitler’s fascism is almost nothing!” She continued:

I wanted to write some more, but I am very tired. Those without the experience won’t know: although you don’t bleed a lot when you write a blood letter, still it drains your mental energy! Moreover I have already written three protest statements in blood today! I cannot help it.… I am practically speaking in my own blood every day! However, they see it as usual and nothing startling!…

I am tired. Let me write you again tomorrow! My Mama, I wish you from afar peaceful dreams tonight!

Your daughter Zhao,

November 1, 1967, the Lord’s calendar

No. 14 of Lin Zhao’s blood letters to her mother was entitled “The Farce on the Sabbath Day,” which she wrote on November 5. “Dear Mama, there was a scene of farce just today: led by a female guard who had inflicted serious insults and injury on me, and whom I had cursed before, a motley crowd gathered in front of my cell to sing wildly,” she reported. “There were songs that wish Mao Zedong ten thousand years, that denounce reactionaries.… You can’t call it a struggle session, because it didn’t look like one, nor did it look like a demonstration. They were thrusting their arms and stomping their feet, acting like buffoons!”

The buffoonery on display was in fact no laughing matter but was meant to be a straight-faced revolutionary ritual. Since the beginning of 1967, when a People’s Liberation Army Daily editorial called on all Chinese to be “boundlessly loyal to Chairman Mao,” collective expressions of “three loyalties and four boundless loves” had steadily gained popularity and would eventually be sublimated into the “loyalty dance,” representing tens of thousands of hearts beating in unison for the great leader. The dance would be invoked during meetings, at street intersections, and on buses, trains, or airplanes. Prisons were hardly off limits.12

Among the revolutionary inmates whom the guard brought that day was one of Lin Zhao’s tormentors, a former prostitute. “But when you think about it, these totalitarian thieves are not much more reputable than prostitutes!” Lin Zhao told her mother.

“What did I do then? I praised the buttocks of Mao Zedong, their stinky progenitor of lowlife, as the greatest buttocks! I chanted long live prostitutes of both the private and public kinds! Long live male prostitutes and long live public toilets!” She found herself getting into the act. “And to express my profound appreciation and heartfelt adoration of Mao Zedong Thought, I put on my head a pair of underpants that had been torn by them in a previous scuffle and a pair of long pants that had been splashed with sewage water, waving the leg parts, mincing about, and singing.… In sum: it was a scene of total devilry!”

Some in the crowd started chortling. “You may not believe it but even I could not help chortling!” Lin Zhao added. “At the very end, a fool jumped out from the crowd and, prostrating herself on the ground, kowtowed to me! That’s when they made an excuse to exit the stage all at once! Good Heavens! There should be such a thing in this world!”

The farce in front of Lin Zhao’s cell that day convinced her that there was no point continuing to write her blood protest statements, which she had been sending to the prison authorities almost daily for about three weeks. “Since the military takeover of prison by upper-strata totalitarianists, they have been doing whatever they want, with no regard for any law!” she wrote. Meanwhile, she would “persevere in writing these daily blood letters home. Not only are they true records of my life and feelings during this period, they are also forceful denunciations of these totalitarian thieves! Dear Mama, my battle is hard, but it also tempers me and makes me more mature and stronger! Sabbath-day blessings to you!”13

On November 8, Lin Zhao dumped her ration of drinking water and then went on an all-morning protest. Through the iron bars of her cell, she shouted about her family’s past work for the CCP, including her own. These reminiscences triggered “irrepressible grief and indignation so that I broke into tears and started weeping,” she told her mother.14

Cold Porridge, Cold Meal, and Cold Water

(No. 18 of Blood Letters Home in Protest)

Dear Mama, it is getting cold. Are you all well? I miss you all, even though there is nothing that I can do for you, just as there is nothing that you can do for me.

At dusk I retrieved the cold lunch that I had left at the door underneath my blood writing, which I did as a protest. I brought it back in a little early…

It’s getting cold; the cold wind rattles the window panes, but I am still sleeping on the concrete floor and my quilt is not yet sewn up!… It was so windy today but they purposely had an inmate housekeeper open the window near my cell to let the wind blow at me.…

I will write to you again tomorrow, my Mama. Now I am going to read aloud my letter. The last few days I have been reading aloud into the open space my blood letters to you, so that more people may know what I have encountered! I wish you good night, dear Mama!”

Your daughter Zhao,

November 9, 1967, the Lord’s calendar

Lin Zhao called her nineteenth letter home, dated November 10, “The ‘Cold Water’ that the Heavenly Father Splashed into the Prison.” As Shanghai’s winter crept in, her thoughts turned to her increasingly dire conditions. “Mama, if you can now see the scene outside my cell door, you will surely be aghast with fury.” She had smashed her wooden chamber pot once before, and to prevent herself from repeating the act, she had shoved the pot far out onto the gangway, where it now sat in a puddle of dirty water, food residue, and human waste. For days, the unsightly scene remained untouched. Nobody cleaned up the mess. “The smell of my own feces is a lot sweeter and lovelier than [the slogan] Long live Mao Zedong,” she added.

There was another puddle nearby. “The other puddle is the cold water that the Heavenly Father has splashed into the prison… rain water, heavenly water.” It had rained for several days, and the roof near Lin Zhao’s cell had leaked. On that day, the rainwater had mixed with the wastewater.

But what significance does it have that is worth mentioning?… This time, the Heavenly Father—my good Heavenly Father—has splashed cold water into the prison. Maybe it was to comfort me, and to show me that the Heavenly Father would splash into prison through a leaking roof the “cold water” I had asked for; maybe it was to spur me on: it shows that the Heavenly Father quite approves of and also directly participates in my water-splashing protests! In any event, I treat this seemingly trivial occurrence as a supernatural testimony.… Dear Mama, I really experienced many astonishing things that bear witness to the Heavenly Father and to the Holy Spirit! Alas, why is there no heaven above my head?”15

In this way, with her mind overwrought but her will intact, Lin Zhao clung to her faith. “There is no greater joy for me as a select soldier of Christ than to know for sure that what I plan to do accords with the Lord’s will,” she added.16

“DEAR MAMA, ARE you dead?!” Lin Zhao’s letter of November 12 began. “One day, anybody reading this out-of-the-blue, illogical sentence would likely wonder: what kind of writing is this?” While she was singing “God Be with You till We Meet Again” the previous night to mourn the death of Ke Qingshi, the guard grew irritated and rebuked her: “You were not so sad when your mother died!”

Lin Zhao admitted that, under normal circumstances, she would have understood that to be just a “tiresome curse.” But she was well aware of Xu Xianmin’s chronic heart ailments and high blood pressure. And she worried that her blood letters might have directed the wrath of the proletarian dictatorship toward her family. “Will they be prompted to persecute you and Younger Brother and Younger Sister?… In the past several years, I have got you all into enough troubles. For that reason, Younger Brother has chastised me and called me the most selfish person in the world!”17

Lin Zhao had been stung before by criticism from her younger brother Peng Enhua, who had grown angry over her stubborn refusal to give up her opposition to the CCP, which had already turned her family members into political pariahs and could have, at any time, even graver consequences. Throughout the Mao era, individuals’ political offenses had always implicated their families, prompting divorces and severing of other family ties—called “drawing a clear line.” Even an urn that contained the ash of a Rightist or counterrevolutionary family member could be a dreaded liability if kept in the home.18

Lin Zhao was not unaware of the implications of her actions for her family but decided that, in her fight as an “independent, free person for the basic human rights endowed by Heaven,” she could not be bound by “considerations for the safety of either myself or my loved ones!”19

By 1967, Lin Zhao’s family had not only become political and social outcasts, they were also bearing a crushing financial burden to support her in prison. The family’s money, such as it was, had evaporated after the Five-Antis Campaign of 1952, when the private bus company Xu Xianmin cofounded was nationalized. By the mid-1950s, Xu Xianmin was unable to afford the better TB medicines for Lin Zhao and Peng Lingfan.

In 1955, based on her exceptional grades, the precocious Lingfan had gained admission into Shanghai No. 2 Medical College, from which she graduated in 1960. She found a job as a physician in a community hospital in Shanghai just before Lin Zhao’s arrest. But Lingfan’s income was modest, and she lived away from home, in a dorm room of her hospital. Enhua, though a bright student, had been unable to attend college, most likely because of his eldest sister’s incarceration as an “active counterrevolutionary.” During the 1960s, he devoted himself to the study of Japanese haiku, about as far from politics as one could get.20

With dwindling resources, Xu Xianmin, who received a monthly stipend of only twelve yuan, had trouble keeping up with Lin Zhao’s requests for money and supplies. The family at times complained about the list of items she wanted from them. Lin Zhao admitted that it had been selfish of her to request supplies from home. “Our family has got into no small trouble because of me. What right do I have to ask for things? On the other hand, Mama, no matter what circumstances one finds herself in, there is always the wish to rebuild one’s life.… And as long as one’s life drags on, there will naturally be various needs in life, and that is something I cannot help with.” She was torn between her guilt and her craving for canned food, glucose powder, soap, shampoo powder, used clothing, stamps, and money, which she could spend on other necessities such as toilet tissue.21

“I have been unable to repay you in any way for the favor of nurturing me or to bring you some consolation in your old age,” Lin Zhao had written her mother in July 1967, after she was again hospitalized. “Instead, I have brought you grave distress. It breaks my heart whenever I think of this!” All she could offer her mother were prayers. “Oh, Lord, Please bless my mother’s life!… I am willing to have my own lifespan shortened so that my mother can live longer! Let Mother live until the day when righteousness triumphs!”22

BY MID-NOVEMBER, THE cessation of family visits had brought considerable hardships, including a lack of money with which to buy toilet tissue. Blood writing was also becoming more difficult, as her blood became thinner and coagulation worsened.23

Lin Zhao’s mother had urged her during one visit to “endure some idleness.” “But you don’t know that I am by nature incapable of inactivity!” she explained in her letter of November 15. “Apart from writing, there seem to be endless chores to do.” Even though the abuse and cold weather had sapped her energy, she was “giving full play to the spirit of Robinson Crusoe.” When an old pair of pongee pants wore out at the hips, she took them apart and altered them.24

At Tilanqiao, inmates could borrow sewing needles for a few hours twice a month. On the other days, she could still hand-sew “almost any clothing” even without a needle, employing a technique she had picked up at the Shanghai No. 1 Detention House: she would use a bamboo pick to poke holes in a piece of cloth and guide the thread through with a strand of hair. “Our circumstances are somewhat different from those of Robinson’s… I’d rather be Robinson! What happiness it is to be close to nature! Even those cannibalistic savages can be seen as unaffected and simple to be point of being lovely when compared to the totalitarianists who are filled with evil!”25

Without family visits or spending money, prison life grew more difficult by the day. Her intermittent hunger strikes left her lips parched and her body feverish. Yet she continued to write her blood letters. “In the past month, these blood letters home have run into approximately 20,000 to 30,000 characters,” she wrote Xu Xianmin on November 16. “In the future, they will make up yet another volume of either my complete published works or a posthumous collection of my papers.”26

Her supplies were running low, she told her mother. She still possessed a few sheets of writing paper but only one envelope. “This month, they did not let me draw on my big account!”—there was no money left in it. Cash brought by family during prison visits was left with the authorities and its amount entered into a notebook—called the big account—from which purchases were deducted. “I already ran out of stamps and toilet tissue, and I have to wipe my poop with my hand!”27

After nearly a month of writing her daily blood letters home, Lin Zhao came to realize that they had had no impact. She had handed her letters to the guards each day to be sent to her mother but had not received any words from home. On Sunday, November 19, as she sang hymns and conducted her one-person worship in her cell, she began to feel “a lack of intensity in my fighting spirit to merely give vent to my sentiments about home.” She admitted to herself that she had sunken deeper into despair and hatred; it appeared that the “totalitarian scoundrels are all beyond cure.” She was ready to bid farewell to the previous stage of struggle, as her mind turned to the prospect of “fortifying the wall and clearing the fields”—by which she meant the scorched-earth tactics she had previously foresworn.28

“Dear Mama,” Lin Zhao wrote in the thirtieth daily blood letter, on November 21. “I am going to bring to a close for now the protest letters addressed to Mother! On the one hand, I don’t know how you’ve been lately. On the other hand… the theme has become a bit narrow in view of the struggle I am faced with.” The physical and emotional toll that the totalitarian rule had taken on her was no different from that experienced by “my fellow countrymen throughout China,” she noted.

As she turned her thoughts to other themes, she was also running out of ideas for her letters to her mother. From a literary perspective, writings must be natural, she explained, particularly in the case of those dealing with emotions. She recalled the words of the great Song dynasty poet Su Dongpo that “writings should be like drifting clouds and flowing water.” They “drift when they should drift, and stop when they must stop.… It would be pointless to affect one’s feelings or to write for the sake of writing.”29 On November 22, she wrote the last blood letter home, acknowledging that her sanguinary protest had failed.

I Am Willing to Submit to the Lord’s Will

(No. 31 of Blood Letters Home in Protest)

Dear Mama: After today’s blood letter home in protest, starting tomorrow, I will bring this theme to a stop. Of course you and I will not forget: tomorrow is the seventh anniversary of Daddy’s death!…

In the past several days I have thought a lot… at times quite painfully, because I was reflecting deeply on my own mistakes!… Some of them were because of my inexperience in struggle, which are easier to correct; others have to do with the rashness in my own personality, which I have to examine in a fundamental way!… In any case, generally speaking, I tend to be overconfident in handling various problems! This is a serious problem especially for a Christian! There is too much of “me”; as a result there is too little, or almost nothing, of the Lord!… I affirm myself too much! And I forget my Lord! I forget that, in my proper station, I am but a servant!… Alas, dear Mama, how hard it is for faith to come from the flesh!… On the outside, I appear to have quite a bit of faith, but that is only faith in myself!… What am I able to do without the Lord’s permission, without the Lord guiding and keeping me?…

Dear Mama, I am willing to learn to submit to the Lord’s will.… Let me turn over all my pains, hopes, and dreams to my Lord and let my heart and soul become the sacred temple where I worship the Lord!… I am quite willing to be silent so that I can think deeply and pray: may the Heavenly Father help me prevail over the devil!

Dear Mama… in the bleakness of my mood I send you and Younger Brother and Younger Sister my painful love and thoughts from afar.

Your daughter Zhao,

November 22, 1967, the Lord’s calendar

Lin Zhao’s sudden urge to plunge herself into self-denying submission to God’s will was uncharacteristic but not entirely surprising. It is true that there had been little quietist spirituality in her early Christian upbringing—the reformist social Christianity the Southern Methodists had introduced to Laura Haygood students during the 1940s tended not to cultivate any mystical quietism. On the other hand, an indigenous Chinese Christian spirituality—most forcefully articulated in the end-time “dispensationalist” theology of Watchman Nee, founder of the homegrown group called the Little Flock—had taken firm root by the time of the Communist takeover in 1949. It impelled a believer to go to extravagant lengths to deny the flesh and crucify oneself in Christ.30

During her initial pretrial incarceration in Tilanqiao in 1963, Lin Zhao had come into contact with Yu Yile, the independent preacher and graduate of the Christian Bible Institute of Nanjing, who may have passed on to her the mystical theology of Watchman Nee. Apparently Yu had tried, without success, to bleach Lin Zhao’s Christian faith of political activism. Now that her protest had been stonewalled, she found the theology of yielding increasingly relevant and appealing.31

But even if Lin Zhao was “willing to be silent,” she was clearly incapable of actually doing so. The following day, to commemorate the anniversary of her father’s death, she fasted and, suddenly energized, embarked on three writing projects. In the first piece, a blood-inked declaration, she explained the basis of her political stand. It included the precept, articulated by a seventeenth-century Confucian scholar, that “the rise and fall of all under heaven is the responsibility of every ordinary person.” It also included Western democratic ideals, which the United Nations had come to embody, and “the humanism and the ethics of love rooted in Christian teachings.”

She had come to realize her own political naïveté—her belief that reasoned remonstration would lead to changes in the totalitarian rule, or that the Communist leaders might repent of their sins. There had been “errors” on her part in the preceding months: she had overestimated the importance of her opposition to the CCP. She now recognized that she was only “one ordinary soldier in the general warfare of free humanity against communism and against tyranny.”32

IN MAO’S CHINA at the time, there was hardly any sign of the “general warfare of free humanity against communism” that Lin Zhao had imagined. Yet there were a few others who had the audacity to question, however momentarily, the CCP revolution. At a time when the majority in China were gripped by “the starkest madness” of revolutionary “sense”—to borrow Emily Dickinson’s words—they, like Lin Zhao, were driven by the “madness” of “divinest Sense.”33

In 1965, Wang Peiying, a housekeeper working for the Ministry of Railways in Beijing who had been treated for mental illness, withdrew her CCP membership, citing the party’s degeneration from a party of liberators to one of pampered and privileged oppressors. She was arrested in 1968 and sentenced to death in 1970. As she was being paraded through the streets on the way to the execution ground—standing in the back of a truck—the guards tied a rope around her neck to prevent her from shouting protests. They did it so tight that the rope strangled her before they reached the destination.34

In Shanghai, counterrevolutionary madness doomed one of the best-known musicians in China. Lu Hong’en, a classical pianist and conductor of Shanghai Symphony Orchestra, was treated for schizophrenia in January 1965. A year later, Lu’s symptoms returned. At a political study session in May, he publicly disputed an editorial by Yao Wenyuan entitled “On ‘Three-Family Village.’” Like his earlier editorial attacking Wu Han’s play Hai Rui Dismissed from Office, Yao’s new article was used by Mao to bring down the party leadership in Beijing, a prelude to the Great Helmsman’s final assault on President Liu Shaoqi, who would be denounced as “China’s Khrushchev.”

In his agitated state, Lu Hong’en defended Khrushchev’s “revisionism” and chanted “Long live Khrushchev.” He had long been known for his politically inept straight talk. At an earlier group study session, he responded to Mao’s 1942 “Talks at the Yan’an Forum on Literature and Art” by asking: “Should Beethoven look up to workers, peasants, and soldiers or should it be the other way round?” His advice—which soon enough was deemed evidence of his “bone-deep hatred for workers, peasants, and soldiers”—had been that the latter should take the time to learn to understand symphonic music. Instead of being sent back to the mental hospital, Lu was arrested and put into Shanghai’s No. 1 Detention House.35

As the Cultural Revolution gathered steam, public denunciations of reactionaries became a favorite part of the revolutionary liturgy. To show off their newfound power, many rebel groups went to the Shanghai No. 1 Detention House to borrow high-profile inmates for their denunciation meetings. Lu was in high demand.

In a packed theater, forced to wear a dunce cap, Lu remained oblivious to the world around him, which had been turned upside down. He was scornful of the revolutionary “model plays” that Mao’s wife had championed, which he privately called rubbish. Their exclusive performance would lead to the “destruction of the tradition,” he warned the crowd. At that point, angry revolutionary rebels rushed forward and ripped his mouth. As his cellmate recalled, Lu returned to the jail bloodied and unable to chew his food—but still humming “Ode to Joy” from Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony.36

Within months, repeated denunciations, brutal handcuffing, and beatings reduced Lu Hong’en, then in his late forties, to a graying and balding shadow of himself. He also experienced bouts of madness during which he screamed in terror that “the witch”—Mao’s wife, Jiang Qing—had come for him. He developed a conditioned reflex to the color red and would rush to smash or bite anything that color; he would also bite inanimate objects that had the syllable mao in their names, be it a towel (maojin) or a sweater (maoyi). “In this ‘great revolution’ stirred up by the witch, I, Lu Hong’en, would rather be a counterrevolutionary,” he declared. He asked his fellow political prisoner Liu Wenzhong—the disabled brother of the executed counterrevolutionary Liu Wenhui—to visit Vienna and lay a bouquet of flowers on Beethoven’s grave for him if he ever got a chance. Thirty-three years later, Liu made good on his promise.37

Lu had been raised a Catholic. Like Lin Zhao, he found solace in hymns and prayers during his more than two years at the No. 1 Detention House. On April 27, 1968, Lu and six other “active counterrevolutionaries” were sentenced to death at a public trial held in Shanghai’s Cultural Revolution Square—formerly the Cultural Square—as part of a ritualistic cleansing of Chinese society ahead of May 1, International Workers’ Day. The condemned were then “immediately sent under guard to the execution ground to be shot by firing squad,” Liberation Daily reported. “At that moment, the revolutionary masses both inside and outside the square broke into a prolonged chanting of slogans. There was not a single person who did not clap his hands in joy.”38

“From being an art of unbearable sensations punishment has become an economy of suspended rights,” Michel Foucault wrote of the evolution of the Western penal system since the Enlightenment. The modern “rituals of execution,” he observed, have been characterized by “the disappearance of the spectacle and the elimination of pain.” Revolutionary China kept both.39

CUT OFF FROM the world, Lin Zhao probably knew nothing about what befell other “enemies of the people.” However, after almost seven years behind bars, she had few illusions about the stark reality outside Tilanqiao. “I do know about Auschwitz and many other concentration camps,” she wrote, “and I know Khrushchev’s ‘Secret Speech’”—the 1956 address in which he denounced Stalin’s cult of personality and “his intolerance, his brutality, and his abuse of power” in the vicious purges. “But what can you find therein that is comparable to all that I am talking about? Simple death, even cruel physical torture, seems almost lovely compared to the vicious humiliation and barbaric trampling that one has to endure!”40

Lin Zhao titled the second piece she wrote on the anniversary of her father’s death “Battle Song of My Heart and Soul!—I Cry Out to Humanity.” She did it in ink. As “one small, young soldier” holding out on the battlefield, “I appeal in anguish to free humanity to please extend righteous sympathy to the Chinese masses who have been enslaved, oppressed, trampled, hurt, and dehumanized,” she wrote. Her only hope was for her case to come before “the supreme court of humanity’s conscience.”

“I have persisted in wrestling my basic human rights from the totalitarian system and from Communist demons, because I am human! As an independent, free person, I am entitled to my birthright, which is my share of God-given, intact human rights!” And since her individual rights were “inseparable” from those of her compatriots, “our fight for ourselves is also the fight for our country… and for all the enslaved.”41

“Prison is the battleground for my resistance!” she wrote, reiterating a declaration she had made years before. Given the political reality in Mao’s China, “this is the only battleground for true resisters.” The “internal battleground,” on the other hand, “is the heart and soul of the resister.”42

“Father’s Blood,” Lin Zhao’s last long piece of writing, ran to about 14,500 blood-inked characters. She started writing on November 23 and finished on December 14. It was her attempt to come to terms with the loss of her father and with her own troubled relations with him. Coming one month after her arrest in October 1960, his gruesome death had been hidden from her until late summer the following year. “It was entirely my fault that we had a fraught relationship,” she wrote—a realization that had come too late, she admitted.

His death could not be deemed meaningless or futile, she maintained. If nothing else, he had refused to bend to the evil power of the Communist regime. Denounced as a “historical counterrevolutionary,” he had refused to plead guilty, as she herself now did. “Thank God! For the past eighteen years, there still remained in the foul-smelling Chinese mainland some so-called ‘diehards’ who refused to bow and ‘plead guilty’ before the Communists,” she wrote. They had struggled to maintain the “Chinese code of honor,” as articulated in the ancient teaching that “a scholar may be killed but would not be insulted.”

Yet, destroying the human dignity and moral confidence of the individual was precisely the goal of the CCP, she argued. It had sought victory through “defilement” and would step on the head of whoever refused to bow. She was reminded of a fable in which a “stinky fly” flew up the sacred Mount Tai to defecate. “After that, it buzzed triumphantly, proclaiming: what is extraordinary about Mount Tai, after all? I shitted on top of it!”

As Lin Zhao put it, the CCP had created masses of downtrodden heretical people, or yimin, a term she coined to refer to all those who had found themselves victims of political purges and who were “more despised than the untouchables in the Indian caste system.”43 The abuse and persecution were so pervasive that “monks in Buddhist temples were forced to draw up ‘patriotic covenants’: they vowed not to chant sutras to expiate the sins of the ‘counterrevolutionaries’ who died!” she observed.

That left the heretical people with but one escape—through death, “which has become both protest and release.” They left behind “a puddle of blood as silent protest in grief and indignation.” She admitted that she had also attempted suicide more than once. She continued:

Blood! Blood! As a Christian I wish to plead with all the Christian churches and the Holy See in Rome: judge the multitude of suicides in mainland China with fairness!… Do not view all the suicides of the victims of Communist… rule as spiritual evil!… God’s gift of life should have been in itself beautiful! Therefore it is sin to lightly dispose of it!… But it is precisely in order to protect the beauty, dignity, freedom, and purity of life that multitudes of victims in China have forsaken their precious lives in resolute protest against the defilement and trampling of life.… I imagine that the Heavenly Father will not necessarily pronounce their suicides sinful but will instead pardon the afflicted souls with compassion! Therefore, righteous and holy churches, please hold a memorial service, or a holy Mass for the repose of the soul, for those who died under the tyrannical rule in mainland China!

Without such sympathy, Lin Zhao asked, where could the dead “find a trace of human warmth to cover their wronged bones”? It was only by imagining a listening, free humanity that she could find solace. “It is only when I think of you, and picture myself pouring out my heart to you, that my anguished yet numbed heart and soul feel the human warmth.”44

IN THE PAST, Xu Xianmin’s visits had meant a brief respite for Lin Zhao from her lonely torment, but now those visits had stopped. “Dear Mama! Are you alive?” she asked once again in a letter dated December 16. The prison had finally given her toilet tissue, she reported, but her menstrual period, which she sometimes missed for months, had stopped once again.45

On December 29, 1967, a cold, icy day, Lin Zhao at last received a letter from her mother that had been sent three days earlier. The extent of self-censorship in the letter is unclear. It explained that she had been gravely sick and near death, only to be brought back to life in the hospital. “Therefore what the comrade in charge told you was completely correct,” she wrote. Cryptically, she admitted that “I have not had the courage to write back to you. Nor have I had the courage to come see you. Your action and your language have been too excitable, too absurd, and too nonsensical.” She added that her two other children and her friends had urged her to cut off contact.

Xu Xianmin also told Lin Zhao that she had previously looked upon the monthly prison visits and the correspondence between them as fulfilling “my utmost desire in life,” but she had come to see that both only occasioned disappointment and pain. She once passed out on her way home from prison. “You are a part of me. Why do you insist on creating such serious consequences?… Do you still have a trace of love for me?” She pleaded with Lin Zhao to “become sensible again” and to listen to her, and promised to come see her in prison the following month if her own health improved.46 Xu Xianmin did not know that she would never see her daughter again.

Lin Zhao received the letter in the evening, a few hours after her brother delivered a package of supplies from home, but she was not granted a family visit that day. “Seeing your handwriting and knowing that you are still alive, that was my only consolation! Dear Mama! This has become nearly the only thing that I care about now.” She had broken down in a fit of crying a few days earlier when she put on the gray sweater her mother had given her, but “entrusting you into the hands of the Heavenly Father” was the only thing she could do. “Oh, Heavenly Father… I ask of nothing other than keeping Mother’s physical life!”47

In Lin Zhao’s last extant letter to her mother, written in ink and dated January 14, 1968, she responded to Xu Xianmin’s complaint that she had been “nonsensical.” It was true, Lin Zhao allowed, that she had been accused of being nonsensical ever since she was in the No. 1 Detention House. But “what am I being ‘nonsensical’ about? Am I the one who is being ‘nonsensical’?”

She told her mother that she could understand what she was going through, due in part to her own encounter with the mother of Zoya A. Kosmodem’yanskaya while she was a student at Peking University. A young Soviet heroine during the Great Patriotic War, Zoya was a household name in China in the 1950s. As a member of a guerilla group that operated behind enemy lines, Zoya was captured by the Germans. She was stripped, given some two hundred belt lashes, and forced to go outside in her underwear and walk barefoot in the snow. She refused to disclose the identity of her comrades, even during merciless torture.

On November 29, 1941, Zoya was hanged after making a rousing speech: “You hang me now but I am not alone. There are 200 million of us. You won’t hang everybody. I shall be avenged.… Victory will be ours.” In 1942, Zoya was awarded the order of Hero of the Soviet Union. Lyubov Timofeyevna Kosmodem’yanskaya, Zoya’s mother, memorialized Zoya and her brother, also a hero in the war, in her book, The Story of Zoya and Shura, which was first published in a Chinese edition in 1952.48

“It was around 1955 or 1956 when I met her, at Peking University. She made a brief speech to the students,” Lin Zhao explained to her mother. After the speech, Lin Zhao and around a dozen other students escorted Zoya’s mother to her car, presented her with flowers, asked for her autograph, shook her hand, and kissed her. As the car was about to pull away, the heroine’s mother smiled and waved to the students. “Strangely, it was that last glimpse of her… that left an odd feeling and an indelible impression!… Alas, Mama, you did not know this: her smile, though filled with a mother’s love, was one of profound loneliness; it quite betrayed a desolation deep inside her heart!”

Every time Lin Zhao thought of that smile, she could not help wondering: “As a mother, would she rather her own children died heroes or lived as mediocrities or, say, average people? Sincere as the warmth of young people in another country might be, what good was that to her? Could she find a bit of compensation in our flowers and hugs for the emptiness in her heart?”

Lin Zhao reflected on her guilt over having hurt her family, not only her mother but also her siblings and father. “I earnestly hope that, one day, I will be able to make it up to Younger Brother and Younger Sister!” Meanwhile, she agreed that the advice that friends and family had given Xu Xianmin “is completely right! Please never mind me!” she implored. “Entrust everything to God.… Didn’t the Bible tell us not to worry about tomorrow?”49

DID LIN ZHAO sense that the end was near? She was not privy to her death sentence, which was prepared sometime in late 1967 and still awaiting final approval. Yet her last letter displayed little of her characteristic feistiness. It was more meditative and resigned than most of her earlier writings and was tinged with both sorrow and regret, as if she was giving a final account of her life.

“In my deep thoughts, I examine solemnly the history of my own life and repent of the sins that I have committed,” she wrote. “Alas, dear Mama, I had been self-satisfied and self-approving about the straight path of my life and the simple life experience I had had, but when I look at my whole life from the point of view of the repentance of sins, I feel a shock and a deep sorrow that I had never felt before!” Even though “I have no blood on my hands” during the land reform of the early 1950s, “was I not more or less splashed with some blood?” she asked.

Turning to her personal life, Lin Zhao made a cryptic reference to an indiscretion while she was in college. “After the ‘Anti-Rightist,’ in a fin de siècle mood, I abandoned myself to my feelings.” It was a “small lapse in virtue” that was nevertheless used later as “loathsome ‘evidence’” against her. It is unclear whether she was hinting at some brief sexual intimacy with Gan Cui, when they thought they were getting married, or even possibly with her Peking University friend Yang Huarong. The latter, in his reminiscence of the winter of 1957–1958 that he and Lin Zhao shared as political outcasts, mentions that they were “quite intimate with each other” as they tried to “fend off the cold of the winter evenings.”50

Lin Zhao herself had also written in “Chatters of a Spirit Couple” that, in the desolation of the days during the Anti-Rightist Campaign, she and a fellow political outcast had tried to “douse our sorrows with a drink from the cup of Venus.” She now wanted her siblings to “make sure to remember the lesson that I have learned” and handle romantic love with “care and prudence”; and she wished them “respectable, happy marriages.” Lin Zhao also pleaded with her mother to moderate her strong personality, to examine herself, and to confront any “mistake or even sin.”51

She was confident that her mother shared her views. Despite the close watch kept over prison visits and the censorship of her family’s communications with her, Lin Zhao might have learned that her mother converted to Christianity in the early 1960s and was baptized in a bathtub in an underground house church.52

Lin Zhao’s final and the most important confession in the letter concerned a strange “sin” of betrayal she had committed against her mother. During the early 1940s, after Xu Xianmin returned from Western China to the Suzhou area as an undercover agent in the resistance movement against the Japanese, she had entrusted Lin Zhao to the care of her own mother. In time, the grandmother developed an obsessive suspicion regarding Xu, who mingled frequently with men in her covert work. She pressed Lin Zhao to reveal any unsavory details about Xu and would cry and make a scene and accuse Lin Zhao of shielding her mother unless she conveyed lurid secrets.

“In the end, I had no choice but to tell lies and make up stories, which I no longer remember after all these years, something ludicrous in any event,” Lin Zhao wrote. It got to a point where “I became scared whenever I thought of it!… And I realized that if she kept forcing me to continue with those lies, I could not wash myself clean even if I jumped into the Yellow River.”

Lin Zhao did attempt to retract some of those tales later on, only to bring down on herself storms of fury from her grandmother that she was taking her mother’s side. “Mama! The Heavenly Father above knows that I agonized over this for quite some time.… This sin from the past had lain buried in my memory for more than twenty years. I have only dug it out in recent days as I examined my whole life and went through a thorough repentance.” She was making the confession, she added, to “relieve my soul of this part of the burden of guilt.… Dear Mama, are you able to forgive me?”53

As for the present, Lin Zhao assured her mother that she was experiencing no internal turmoil. “They are trying to force me to make an exit, but I am incapable of exiting this stage. Therefore, if they won’t let you come, so be it.” She added that if the prison gate were to be opened for her by “certain people”—with unacceptable conditions attached, she implied—“I won’t even walk out! Speaking of being nonsensical, that is how nonsensical I will be!” She closed the letter telling her mother that she had not eaten that day and was deeply tired.

That night, in a burst of fantasy, Lin Zhao added a postscript consisting of a long list of items she would love to get from home. It began with the usual necessities such as toothpaste, socks, used clothing, a washbasin, a straw mat, pens, composition books, notebooks. Then, her imagination took flight:

I want to eat, Mama! Stew for me a pot of beef, and also slow-cook a pot of lamb. Prepare for me a salted pig head.… Roast a chicken or a duck. Go get a loan if you don’t have the money.…

Don’t cut back on fish either. Steam a lot of salted ribbonfish, fresh milk fish. The mandarin fish needs to be cooked whole.…

And the moon cake, and Chinese New Year cake, dumplings, spring rolls, pot stickers… and zongzi [sticky rice wrapped in broad bamboo leaves]… crackers, fruit cakes… When you run out of the rationing coupons for grains, go ask for them like a begging monk.…

And sausage… duck livers, pig tongues… eels and soft-shell turtles, all simply steamed, to be brought to me in the steam pot.

And—etcetera, etcetera. Load them onto a truck and bring them.… Feed me.… Pig head! Pig head! Pig head!…

Hey! Now after I wrote all this, I took another look at it and I laughed! How often does one get to have a hearty laugh in this world of dust?…

I am sending you a daughter’s love and longing, my Mama!54

The fantasy was in season: in two weeks, another Chinese New Year would be ushered in; in each home, on New Year’s Eve, there would be a family reunion dinner, the most lavish of the entire year—or so it was in her childhood and adolescent memories.

LIN ZHAO’S PRISON writings, which were returned to her family in 1982, include nothing from her final three and a half months in Tilanqiao. Did she stop writing altogether? That seems unlikely. Was her stationery taken away from her, as had happened during her time in the No. 1 Detention House? That is possible, but she would have continued writing in her own blood—although she would not have had the opportunity to copy the words onto her notebook using a pen, as she had been doing.

According to the judge who reviewed Lin Zhao’s prison files in 1981 for her posthumous rehabilitation, prison rules at the time dictated that the writings of the executed not be destroyed. They were to be gathered into the inmate’s files. What was eventually returned to Lin Zhao’s family came from her secondary file. The rest, which would have included her interrogation records and possibly her other writings deemed as key evidence of her counterrevolutionary crimes, was sent to a storage facility for classified archives outside Shanghai, where it remains.55 Until her primary file is declassified and made public, what she wrote after January 14, 1968, remains a mystery.

Shanghai High People’s Court records show that on April 16, 1968, the Military Control Committee in charge of Shanghai’s public security and judicial system formally approved her death sentence.56 The verdict ends with the following, which Lin Zhao would have scorned as much for its shoddy composition and revolutionary clichés as for the miscarriage of justice it represented:

Throughout the interrogation process, Criminal Lin refused to plead guilty and displayed instead extremely rotten attitudes.

The counterrevolutionary criminal Lin Zhao started out as a counterrevolutionary of grievous crimes. During the reform-through-imprisonment period, she stubbornly stuck to her counterrevolutionary stand and continued counterrevolutionary activities inside prison. She is truly a diehard, unrepentant counterrevolutionary. In order to defend to the death our great leader Chairman Mao, to defend to the death the invincible Mao Zedong Thought, and to defend to the death the Party Central Committee headed by Chairman Mao, as well as to strengthen proletarian dictatorship… this committee issues the following verdict:

Death sentence for the counterrevolutionary criminal Lin Zhao, to be carried out immediately.57

Strangely, the verdict carries a serial number indicating that it was initially prepared in late 1967. Why there was such a delay remains a puzzle. In any event, on April 19, the Shanghai Revolutionary Committee, of which Zhang Chunqiao and Yao Wenyuan—ideological stewards of Mao’s Cultural Revolution—were head and first deputy head respectively, signed off on the execution warrant. “Criminal Lin made no demand in response to the sentence,” a formulaic note in her court file reads. In reality, Lin Zhao reportedly did her last blood writing upon receiving the verdict. It reads, “History shall pronounce me innocent.”

On the same day, as a matter of formality, the verdict was referred to the Supreme People’s Court in Beijing for final approval—a remarkable gesture toward nominal legal procedure amid a general breakdown of law and order across the country.58

By 1968, the Supreme People’s Court had all but lost its judicial functions, a culmination of political developments since the 1950s. In 1963, the Supreme People’s Court and the Supreme People’s Procuratorate began to combine their respective roles. The two institutions’ joint work report for that year—delivered to the National People’s Congress that oversaw both—highlighted their support of the political campaigns then underway. Beginning in 1964, when the third People’s Congress was formed (each served for five years), “class struggle” became the dominant theme for both the Supreme People’s Court and the Supreme People’s Procuratorate. Their overriding goal was to “beat back the enemies’ savage onslaught.” Even civil cases were to be handled with a view to carrying out “class struggle.” Any questioning by the Supreme People’s Court of Lin Zhao’s death warrant was thus inconceivable. Its approval was granted on April 23.59

BY THAT TIME, Lin Zhao had been moved from the Women’s Block to Building No. 3, the special ward for political prisoners, which also served as a holding place for those in transition into or out of prison, including inmates on the death row. A five-story brick structure completed in 1920—it was the oldest cell block in service inside Tilanqiao—Building No. 3 stands near the northwest corner of the prison, a few meters away from Zhoushan Road outside the prison wall. Originally called Cell Block F.G.—a reference to the two wards, F and G, inside it—it was euphemistically renamed the Humaneness Block in the late 1940s, during the last years of the Nationalist rule. After 1949, under the new Communist government, which had no use for Confucian sentimentalism, it became Building No. 3, until the Cultural Revolution eventually militarized its name into Squadron No. 3.60

Lin Zhao was left in a cell on the otherwise empty fifth floor, where the effect of any shouting would be minimized. The prison took further precautions to prevent her from ideologically contaminating anyone: a tight rubber hood, called the Monkey King cap, was placed over her head. It covered her entire face, leaving only a narrow slit around her eyes and an opening for her nose to allow her to see and breathe. The hood was only removed at mealtime. During this period, Lin Zhao was almost certainly handcuffed behind her back and was likely in fetters as well.61

Lin Zhao’s “Monkey King cap.” Oil painting by artist and filmmaker Hu Jie. Used with permission from Hu Jie.

On April 29, Lin Zhao was taken to a choreographed “public sentencing meeting” at the one-thousand-seat prison auditorium, a massive gray structure at the northeastern corner of the prison that stands atop Tilanqiao’s former open execution ground.62 As was customary, other inmates were summoned to attend the meeting, to lend their revolutionary indignation to the condemnation of the most notorious “antireform element” at Tilanqiao and to be shown the consequences of resistance.

Lin Zhao arrived not from her cell but from the prison hospital, where she had been taken after coughing up a massive amount of blood in another flare-up of tuberculosis. When the soldiers acting under the order of the Military Control Committee at Tilanqiao rushed into the ward for Lin Zhao, she was in bed, hooked up to an intravenous line. As the doctor who had been treating her later recalled, her weight had dropped to about seventy pounds but her eyes still flashed with intensity. “You diehard, unrepentant counterrevolutionary,” one of the soldiers cried out, “your last day is here.” Lin Zhao calmly asked for permission to change out of the hospital gown, a request that was denied. She then asked a nurse to bid farewell for her to her doctor. The doctor, hiding in the room next door, heard the commotion but silently remained there, out of her sight, trembling.63

As shouts of revolutionary slogans reverberated around the auditorium that afternoon, Lin Zhao stood soundless on the dais, her face and neck flushed—as a former inmate who was in the audience recalled—and her mouth stuffed with a rubbery gag, called the shut-up pear, that expanded in the inmate’s mouth at any attempt to speak. As a precaution lest the gag malfunctioned, a thin plastic rope was also wound around her neck, to be tightened if necessary, as a backup silencing device.64

IN THE LATE 1960s, many public executions in Shanghai took place at the Target Ground, five kilometers to the northwest of Tilanqiao Prison, where an artificial mound at the end of a shooting range had been built by the Japanese army following its occupation of Shanghai in 1937. After 1949, it remained in use as a firing range for troops and local militia but later doubled as an execution ground. During the Cultural Revolution, a column of trucks would sometimes be seen carrying the condemned—tied up with ropes, two or more to a truck—from their public trials through the streets of Shanghai to the Target Ground. “Counterrevolutionary criminal” Shan Songlin’s execution on August 28, 1967, most likely happened at the Target Ground.65

According to Lin Zhao’s sister Peng Lingfan, a family friend’s young son, who occasionally worked at the then decommissioned Longhua Airport in Shanghai, claimed to have witnessed Lin Zhao’s execution. At about 3:30 p.m. on April 29, he reported, two military jeeps sped onto a Longhua Airport runway and then came to a sudden stop. Two armed men dragged out a woman with her hands tied behind her back and her mouth stuffed with a gag. She looked as if she was wearing a hospital gown. From a distance, the boy recognized her as Lin Zhao. One of the men gave her a kick on the back, and she fell forward on her knees. At that point, two other personnel emerged and fired a shot at her. She fell but then raised herself from the ground and struggled to inch forward. Two more shots were fired, and she went limp. They then dragged her body into the other jeep and sped off.66

In reality, however, Lin Zhao’s execution did not take place at Longhua Airport or the Target Ground. The retired judge who presided over Lin Zhao’s rehabilitation confirmed that there was indeed an execution ground at the time next to Longhua Airport but revealed that Lin Zhao was not taken there. Instead, after the sentencing meeting, she was shot at a location within Tilanqiao. This revelation accords with other credible accounts, including the recollections of a former inmate housekeeper, who claimed that Lin Zhao’s execution took place in the back of the auditorium.67

What went through Lin Zhao’s mind as she was led out to be shot that afternoon, her hands tied behind her back? She could not have been taken entirely by surprise, however secretively the execution order had been passed down the chain of command. In January 1966, more than two years earlier, she had reflected on her political dissent and its probable outcome: “Under the current circumstances, besides treating the prison as her homestead, Lin Zhao only looks to the execution ground as her final place of repose!” Her “long-cherished hope” was to “turn my purest heart and my youthful blood into an exclamation mark in the epic of the struggle of free humanity,” she wrote. “By nature people find joy in life; I alone find joy in death!”68

Meanwhile, Mao’s revolution surged on, enraptured by its own purity and its moral triumph over both its domestic enemies and Western imperialists. The day of Lin Zhao’s execution, the New China News Agency announced that a historic pamphlet by Mao, entitled “Statement by Comrade Mao Zedong, Chairman of the Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party, in Support of the Afro-American Struggle Against Violent Repression”—Mao had written it within days of the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. on April 4—had been translated into seven languages including English, French, and Spanish.

“Some days ago, Martin Luther King, the Afro-American clergyman, was suddenly assassinated by the U.S. imperialists,” Mao wrote. “Martin Luther King was an exponent of nonviolence. Nevertheless, the U.S. imperialists… used counterrevolutionary violence and killed him in cold blood.”69

THE EARLIEST MEDIA report on Lin Zhao in the post-Mao era, a People’s Daily article published in January 1981, contained a detail about her death that has since been etched in the popular memory: after her execution, officials delivered the news to her mother and demanded a five-cent bullet fee, since Lin Zhao had wasted a people’s bullet. The article’s source was Lin Zhao’s sister Peng Lingfan, who apparently heard about the bullet fee from her mother and who later published her own accounts of the incident, which included additional dramatic details.70

Lin Zhao herself had commented on the Communist state’s practice of demanding a bullet fee. In her letter to the editors of People’s Daily in 1965, she wrote that, outside the official media, “one hears that when a man is sentenced to death, he has to pay for the bullet he gets. One bullet costs just over a dime, it is not a big deal if I have to buy that with my own money.” At least, she observed, that was a straightforward way to die and allowed one to “bleed in broad daylight and before people’s eyes.” It was preferable, she added, to having her blood “dripping drop by drop in a dark corner”—a description of her state, at the time.71

During the Cultural Revolution, the collection of bullet fees had great symbolic value to revolutionaries. Following the public trial and execution of Liu Wenhui as a counterrevolutionary on March 27, 1967, a mob of “revolutionary rebels” and indignant neighbors, led by an officer from the ward police station, descended on his home shouting “down with” slogans while the police collected a bullet fee from his mother. Likewise, after the execution of the musician Lu Hong’en two days before that of Lin Zhao, the authorities demanded a bullet fee from his wife.72

The collection of bullet fees was not the only means of inflicting additional pain and shame on the family of the condemned. On August 28, 1967, the day of Shan Songlin’s public trial and execution, an official arrived at his home to announce the execution and to instruct the family to “draw a clear line” between themselves and Shan. He also had Shan’s death warrant posted on the wall outside his house, as a neighborhood crowd rushed in to smash the door and the windows.

When Shan’s wife and children arrived at the crematorium to claim his ashes, the staff greeted them by vigorously reciting in unison a passage from The Little Red Book: “Whoever stands on the side of the revolutionary people, he is a revolutionary. Whoever stands on the side of the imperialists, the feudalists, and the bureaucratic capitalists, he is a counterrevolutionary. Whoever merely stands with the revolutionary people verbally but acts otherwise, he is only a verbal revolutionary.” Shan’s family returned home that night without his ashes.73

Soon afterward, the Red Guards arrived to search Shan’s house and to remove all pictures of him. “They not only annihilated his body,” Shan’s son reminisced, “they also wanted to wipe off his memory from our hearts.” To atone for Shan’s counterrevolutionary crime, his widow was made to kneel in front of a Mao portrait. Finally, Shan’s small house was confiscated and the entire family thrown out into the street.74

In the course of a few decades, Mao’s revolution had transformed the soulless apathy of the average Chinese that had sickened Lu Xun into a frenzied hatred toward class enemies—and into an equally feverish fear that one would be torched by the fire of the revolution unless it is redirected toward others—colleagues, neighbors, friends, and, in some cases, even one’s own kin. Thirty-two years later, Shan’s widow died from her heart trouble. Her last words were: “If there is rebirth, I vow to never re-enter the womb in China!”75

UNLIKE THE PUBLIC sentencing of condemned counterrevolutionaries in Shanghai—usually conducted in the city’s Cultural Revolution Square in those days—Lin Zhao’s trial and execution took place within Tilanqiao’s high walls and was kept out of the public eye. Therefore, no mob appeared outside her home to vent their class hatred. The five-cent bullet fee was likely collected by an officer from the ward police station. It was part of a routine revolutionary ritual, intended to drive home the point that Lin Zhao’s crime against the party and the people was such that her family must pay to have her cleansed from the revolutionary land.76