Malcolm watched from above, not sure whether to follow. Zsa-Zsa turned round and faced the doorway of the farm.

“Trotsky! Trotsky! Come here immediately!” she cried.

Within seconds, the farm sheepdog had appeared.

“Woof! Woof woof woof! Woof woof!”

OK, thought Malcolm. Clearly, I don’t understand dog.

“Yes, yes. Whatever. Oy!” said Zsa-Zsa, looking up at him. “What’s your name?”

“Malcolm!”

“Malcolm? What kind of a name for a cat is that?”

“It’s not a name for a cat. It’s a name for a human. Cats aren’t called things like that.”

“Hmm. You say that, but I once heard the humans talking about a cat called – get this – Dr. Seuss. That’s a cat who’s a doctor! Not even a vet!”

Malcolm sighed. “That’s the name of the author, not the cat,” he said.

“What’s an author?” said Zsa-Zsa.

“It’s … never mind. Anyway, the Cat in the Hat isn’t a real cat,” he said.

Zsa-Zsa frowned. “Course it is. I saw a picture: furry, whiskers, tail, the lot.”

“The big long hat didn’t trouble you at all?”

“Nope. I assumed he was cold. Anyway, Malc—”

“Don’t call me Malc!”

“I’ll call you what I like. Malc – come down here!”

Malcolm looked down. Directly down. The ground suddenly seemed a long way off. He looked back to Zsa-Zsa. Trotsky the dog was with her, looking up at him, his tongue hanging expectantly out of his mouth.

“How do I do that?”

“Tsk! You’re a cat!”

“No, I’ve told you, I’m a—”

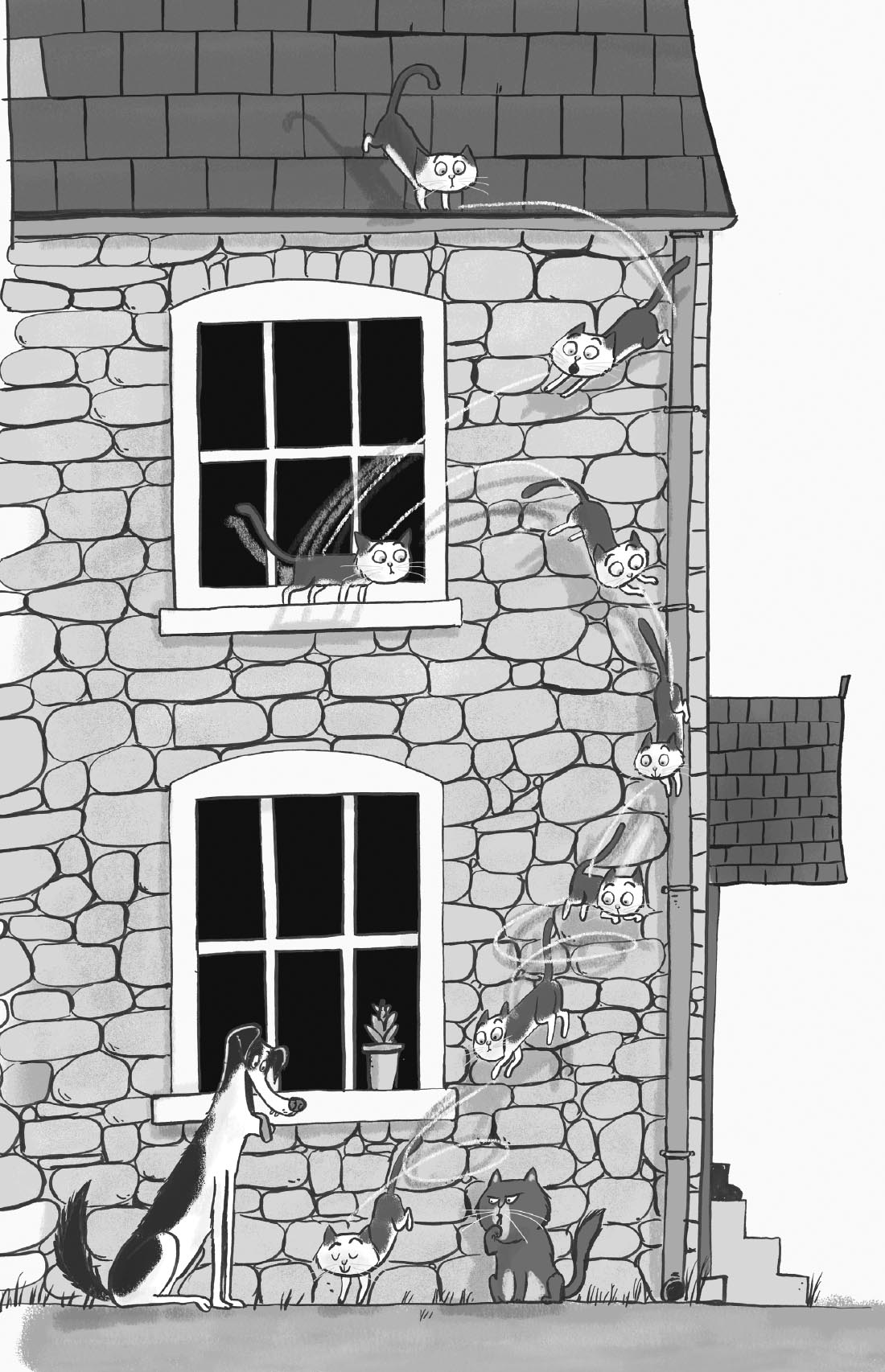

“Look, even if your catamanny story about being a boy really is true – and I have to admit I haven’t seen a cat with eyes that blue before – you’re definitely rocking a cat’s body right now. So I’m pretty sure that a hop on to the guttering, a shimmy down to the window, and a leap from there to here is going to be no problem.”

Malcolm looked down again. It really looked high. Once, back when he had been a human boy – which was starting to feel like quite a long time ago – he had gone swimming with the school, and various boys had dared each other to dive from the top diving board at his local swimming pool. Barry, Lukas, Taj and Morris had all done it (although Morris had more fallen off than dived). But Malcolm couldn’t: it looked not that high from the side of the pool, but once he’d walked up the ladder, right to the end of the board and looked down at the water, it felt like he was on top of a mountain. So, after trembling there for a bit, he just came down again, feeling sure that everyone in his year was looking at him and laughing.

This wasn’t as high as that. Although proportionately it was, Malcolm thought, seeing as back then he had been four-and-a-half feet high, whereas now his head was about eight inches off the ground, or rather, the roof. So in terms of his present size, the drop was actually much, much higher.

So he just crouched there for a while, not knowing what to do and feeling scared. Then he heard Zsa-Zsa shout:

“Come on, Malc!”

“Pardon?” said Malcolm.

“I said come on, Malc! We haven’t got all day!”

Two things got under Malcolm’s fur about this.

“Don’t call me Malc!”

“Why not? It’s short for Malcolm. All cats get their names shortened. Gav and Mav call me Zee-Zee.”

“That isn’t shorter!”

“Eh?”

“Zee-Zee takes as long to say as Zsa-Zsa!”

Zsa-Zsa yawned: this may or may not have been because she was bored. It was a cat yawn.

“Just come down, Malc!!”

Right, that’s it, thought Malcolm. And in his anger, he just leapt into the air. For a moment, his paws whirled madly, as if he had no idea how to direct his flight.

But then suddenly, as if propelled by some internal steering wheel, his sleek cat body twirled towards the gutter, his back legs bouncing elegantly off it, directing him down towards the window ledge, where he landed for a split-second before bounding up again, and – by now thoroughly enjoying himself – spinning round in mid-air, twice, before settling, finally, on the grass exactly in between Trotsky and Zsa-Zsa.

Zsa-Zsa looked at him, wearily. “Yeah. Very un-catlike. I must say.”

“That was fun!!” said Malcolm. “It was brilliant!”

“Modest too …” said Zsa-Zsa. “Oh, wait a minute,” she added pointedly, her ears cocked. “What’s that noise?”

“What noise?”

“That noise,” said Zsa-Zsa.

Malcolm listened. He could hear a nice, comforting sound, a continuous breathy vibration, which sounded something like phommm-pharrrr …

“Where’s that coming from?” he said.

“You! It’s called purring, Mr I’m-Not-A-Cat! Anyway, Trotsky …?”

“Woof?”

“Can you ask the tortoises if this cat – Malcolm – was, just a minute ago, a tortoise?”

“Woof woof woof?”

“Yes, I know it’s weird. Just ask them.”

“Woof woof!”

“You won’t look stupid. Or at least, no more stupid than you do when you sniff another dog’s bum.”

“Woof!”

“I do not. Well. Only if it’s a cat I know really well.”

Looking like he wasn’t at all sure about that assertion, Trotsky turned round. So did Malcolm and Zsa-Zsa. Benny and Bjornita were approaching them. Slowly.29

Trotsky went off towards them.

Malcolm asked Zsa-Zsa: “How come Trotsky’s just doing what you ask him? I thought dogs didn’t like cats?”

Zsa-Zsa stared at him. “Now I’m starting to think you might be telling the truth about being a boy …”

“Why?”

“Because all real cats know that that whole cats v dogs thing is just an act. It’s something we do for the humans: for their cartoons and stuff. In real life, we get on really well. Just as long as dogs know their place, of course.”

“Woof woof woof!” said Trotsky. Zsa-Zsa and Malcolm turned round. Benny and Bjornita had finally got close enough.

“OK, Trotsky, ask them! Ask them if Malc here was just one of them …”

“Woof!”

Trotsky crouched down. He sniffed at Benny. Then Bjornita. Malcolm watched, not entirely convinced the dog was going to talk to the tortoises. It looked more like he was about to eat them.

Then he went, in a low growl:

“Sausages sausages sausages. Sausages.” His head whirled round, nodding towards Malcolm. “Sausages; sau-saaaaa-gesss.” His head whirled back to the tortoises. “Sausages sausages sausages?”

“Yes,” said Benny. “If that’s Malcolm, he was just with us.”

“And definitely, then, he looked like a tortoise,” said Bjornita.

“Oh!” said Malcolm. “I can understand you two! Maybe … then … I can understand the languages of animals I’ve … been …?”

“Sorry,” said Zsa-Zsa, “now it sounds like you’re just saying ‘sausages’…”

“I can talk to the tortoises! Hi, Benny! Hi, Bjornita!”

“Hello, Malc!” said Benny.

“Don’t call me Malc!”

“I understand that,” said Bjornita. “Malc-olm. How’s life as a cat now?”

“It’s great!”

“I see. Better than being a tortoise?”

“Er …”

Bjornita turned away, haughtily. “Well, I think your silence speaks volumes. Doesn’t it, Benny?”

“What do you mean, Bjornita?”

“I mean, clearly, he thinks it’s better being a cat than a tortoise …”

“Well,” said Benny, “it probably is.”

“Don’t say that.”

“Sorry. But sometimes I think I’d quite like fur. And speed. And people stroking me. And lots of photos of me looking cute on the internet.”

“Hello?” said Zsa-Zsa. “I have no idea what you chaps are saying to each other. But I am still here. And I am still waiting for an answer to the question: was this cat very recently a tortoise?”

“Woof woof woof!” said Trotsky.

“Oh, use your cat words, Trotsky,” said Zsa-Zsa.

“Woof … woof woof …?” he said quietly.

“Don’t be silly. Your accent isn’t stupid.”

Trotsky raised his eyes, looking a bit ashamed.30 Then he said:

“Yeeeesss. Zeee Tortoize lady-one and not lady-one, zeey sayy zat zey are thinking zat zis kitty is yes Malcolm the boy-human who was also just now a tortoise yes.”

Zsa-Zsa looked at Malcolm. “Blimey …” she said.

“You see!” said Malcolm, feeling vindicated at last.

“… I’d forgotten quite how stupid his accent in fact is.”