ONE

How Companies Transform

In 2012, Lowe’s, the North American hardware retailer, was in a familiar spot. Despite being one of the leading home improvement retailers (selling hammers, paint, and other products to the $30 billion North American DIY and professional market), Lowe’s never seemed able to catch up to archrival The Home Depot, let alone be first in its industry. To make matters worse, a quick glance at a retail outlet map revealed an overwhelming sea of stores saturating the market. Searching for growth, Lowe’s had begun expansion forays into Canada, Mexico, and Australia. But results had been disappointing; an acquisition attempt had been publicly thwarted in Canada, while store closings and corporate layoffs were taking place in the United States.1 Meanwhile, several promising innovation efforts had fallen flat, leading to more losses and unfulfilled growth promises. As Lowe’s faced its future under the harsh spotlight of quarterly earnings pressure, the retailer seemed caught in the same bind that troubles so many other large companies: the company was big, profitable, risk-averse, and tethered by quarterly earnings. Its own success in retail meant that it lacked the motivation, capabilities, or support from shareholders to do something transformational. The future looked like more of the same; Lowe’s expected a grinding battle to try to break out of second place.

Fast-forward six years to 2018. Lowe’s has helped send the first 3-D printer into outer space, developed the first 3-D print and scan services in stores, and built some of the first 3-D imaging capabilities in the world.2 It has also introduced some of the first retail robots in actual use; they greet customers in stores and take inventory at night.3 Lowe’s is also developing exosuits—external robotic skeletons that help workers carry heavy items.4 Even more surprising, it sold augmented-reality (AR) phones through a collaboration with Google and Lenovo.5 More importantly, these imaginative initiatives are succeeding. The phone flew off shelves, and the 3-D imaging capabilities have been shown to increase conversion of online sales for some items by more than 50 percent.6 The robots are addressing the expensive challenge of keeping accurate inventory when you have a hundred thousand-plus in-store products. The exosuits have generated interest from around the world.7

In addition, Lowe’s reputation for innovation has risen dramatically. The company became an unlikely number one in retail innovation on the Fortune World’s Most Admired Companies list and number one for AR or virtual reality (VR) on Fast Company’s Most Innovative Companies list, even higher than the company that makes the leading 3-D development platform! Meanwhile, since 2012, the stock price increased nearly threefold, adding $45 billion in market capitalization to the company. But what’s more important than all these measures, Lowe’s itself has begun to change—from an ossified giant in the past to an agile, adaptable company taking charge of its future. By any measure, something transformational happened.

Who We Are, and Why We Wrote This Book

Transformation may be one of the hardest things leaders are called on to do. By transformation, we mean seeing the possible, valuable futures for your organization and then successfully overcoming the barriers to creating that future. An organization undergoing transformation might lead a disruptive new business model, a radical innovation, a strategy reorientation, a cultural makeover, or some other significant change. But transformation always requires you to dream bigger about what else your organization can do and then to do something meaningful about it.

Leaders know that their job is to lead transformation to keep pace with technology and an ever-changing business environment. They also know that they are bound to fail doing so. But this discouraging outcome is not because they can’t solve a technological or strategic problem. Leaders will fail because of intractable human problems associated with change—problems such as fear, habits, politics, and lack of imagination. These challenges have always plagued humans, but what if we had a way to transcend them?

This book reveals a radical new method for doing just that—for driving the kind of change described above at Lowe’s and for addressing the real, human challenges of change. As an author team, we bring a unique perspective to this topic. Written by the executive who designed and implemented the process we describe in this book (Kyle), the neuroscientist who designed measurement tools for applying this process to unfamiliar territories (Thomas), and the academic who explains why and how the process works (Nathan), the book introduces an innovative yet proven way of creating breakthrough change. Demonstrated at Lowe’s and Walmart—large organizations that are slow to change—the transformation process and tools have also been used successfully by organizations such as IKEA, Pepsi, Google, Microsoft, XPRIZE, the United Nations, and many others we cannot name. Most importantly, the transformation process has been applied not just by the Googles of the world, but by everyday companies, governments, and nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) to create real change.

Our goal with this book is to describe the transformation process and tools that worked for us and for leaders at many organizations around the world. Rather than describe what we have done individually, much of the time we used the term we to emphasize this shared journey to communicate to you the tools to create an inspiring vision and then to make it happen. We hope to provide you with a road map for leading transformation in your company. Although we can’t cover everything about transformation in a single book, and we each came from different starting points—manager, scientist, professor—all of us sought to answer the same question: how can leaders create breakthrough change? That’s what we hope you will get from this book—a new perspective, a new process, and a new, if not even a bit unusual, set of tools for leading transformation.

Let’s begin by diving deeper into how Lowe’s achieved the kind of results described above.

How Did Lowe’s Transform?

Although you might be tempted to focus on the technology—the robots, the exosuits, or a store in space—the transformation at Lowe’s isn’t about the technology. Instead, the change occurred through a human-centered process designed to overcome the key bottlenecks to transformation. What was the process? Forewarning: the answer may sound a bit outlandish at first. But we are simply applying old tools redesigned in new ways and new tools based on several decades of behavioral science. We then use these tools to address ancient human challenges, namely, the incrementalism, fear, and habits that hold organizations back from transformational change. (For details on these tools, see the sidebar “The Research Foundations of This Book.”)

For example, to develop the tools delivered on AR phones, we started by assembling Lowe’s data about consumer needs and technology trends and then shared this data with a panel of science fiction writers (yes, science fiction, as in Star Wars).8 We then asked the writers to imagine the near future—five to ten years away—when Lowe’s would solve a critical customer problem using technology. The writers returned with a wild array of stories, complete with dystopian overlords in some cases. But surprisingly, many stories converged around a key theme: using VR and AR to address the challenge of envisioning how to remodel a home and then communicate that vision to others.9 We then worked, over several rounds of iteration, to develop a strategic narrative about what the future could be. When we say narrative, we mean a real story, one with a dramatic arc, a protagonist (the user), a dilemma (the customer problem), and a resolution. Then we converted the story into a comic book and distributed it to the executives (yes, comic books … just imagine handing a comic book to your CEO, who has built a reputation and career as a no-nonsense operator who demands results).

But we didn’t stop there. We started building prototypes right away and put high-resolution electroencephalograph (EEG) headsets and eye trackers on customers to understand their reactions to both the stories and the prototypes.10 Using applied neuroscience, we could see the things users couldn’t tell us, for example, how their brains overheated when the users were immersed in VR or how they liked the AR better when the simulation was actually less, rather than more, realistic.11 Most importantly, we could gather live data on people’s reactions and correlate it with a behavioral database to provide data-driven indicators about the best path forward. Along the way, we also intentionally used this information as currency to attract marquee partners such as Google and Microsoft and collaborated with them to provide Lowe’s access to their best technology and teams.

Of course, the transformation wasn’t devoid of struggle and resistance. Although several visionary senior leaders had championed the change, the organization was just at the beginning of the transformation journey.12

For a moment, put yourself back in time to 2012, during the winter of VR, when people remembered VR technology primarily as a failed technology from the 1990s. It was long before people started talking about VR or AR as useful technologies. Kyle had joined Lowe’s the year before with a personal goal of trying to test his theories about how to transform the average big company. (Although it’s fun to talk about Amazon or Google, it’s another matter for a legacy operating company to transform itself.) Thanks to the support of several visionary executives, Kyle had recently gotten his big chance to apply these ideas to transform Lowe’s. Using his science fiction approach, he began to prepare to present to the rest of the staff the AR and VR vision he had created.

Kyle had a great deal of trepidation about the upcoming presentation at Lowe’s. Experience had taught him about the dangers of presenting an unusual idea that challenges the status quo. Recently, he had presented to a group of executives from across several industries (some details disguised to protect identities) about the possibilities of AR and VR. In the meeting, he had described how AR could change the future of how customers interact with many products and services. As he was standing in front of the group, presenting the possibilities, a senior executive from the construction industry started booing. Loudly.

Surprised, Kyle paused to catch his breath.

Then the executive leaned forward in his chair and in a loud voice said, “No, no, no. Nope.” The executive continued: “We studied this exact technology, and it’s ten years away from even getting started. This is a dead end.”

As people shifted uneasily in their seats, Kyle stood momentarily stunned. The presentation could hardly be going worse, he thought.

Then, recovering, he reached into his backpack and responded, “Well, we’ve already done it. I have it right here.” He pulled out an iPad with an Occipital camera—a new kind of camera that could take the measurements of a space when the instrument was pointed around a room. He demonstrated how he could do just this with the camera and next demonstrated how to view a few preloaded digital objects in the actual room on the iPad. In this way, he showed how a user could envision remodeling a space in real time, instantly visualizing a new couch or refrigerator in their space.13

Now the stunned silence seemed to be one of approval. Kyle heard a few wows. At the time, few people were talking about AR, and Pokémon Go had not yet been launched. This technology was truly new. The mixed group of executives began to leave their seats to get a closer look. A few tried out the camera, measuring the stage and then placing a digital refrigerator next to the podium to see how it fit in the space. After a few minutes of using the AR device, the attendees retook their seats. Kyle continued presenting, but after the audience had seen how he had turned science fiction into reality, the tone in the room had completely changed.

Fortunately, when Kyle presented the AR and VR project at Lowe’s, the presentation went more smoothly, with no one shouting him down. The story gave the leaders a reason to believe in a more attractive possible future, and the comic book helped communicate the big opportunity. The prototyping process, as Kyle described it, would benefit from Lowe’s working with uncommon partners—organizations that a company might not normally work with, but which could help it move into new areas—and would demonstrate the feasibility of the vision described in the story. The executives wouldn’t need to wait for Microsoft or Google to bring the technology to them. Even more audacious: Lowe’s could do the work itself!

At the time, Facebook hadn’t yet purchased Oculus Rift, and no one was talking about the future of AR or VR. This technology was truly new. The conversation became not about how AR was impossible for a company like Lowe’s, but instead about how Lowe’s could be the one to lead it. By the end of the process, the Lowe’s leadership team was focused on the opportunity: Lowe’s could become a different kind of company, one that created the future rather than letting it just happen.

Five years later, mixed-reality devices had become the rage. Oculus Rift had been acquired for $2 billion by Facebook and had since begun selling headsets to consumers. Google Cardboard had made VR accessible to everyone. And Pokémon Go had been downloaded by half a billion people in the first two months of its release and made an average of $2 million a day (and over $1 billion in total) as a free app.14 In 2017, Michael Porter wrote a Harvard Business Review article about how every company needed an AR strategy.15 But while other companies were scrambling to understand how to use AR or VR in their business, Lowe’s was already benefitting from it. The retailer was first in applying AR to the massive home improvement market, partnering with Lenovo and Google to introduce an AR-enabled phone for sale for $500 in stores and online—surprising by any measure—but the “digital power tool” sold out in short order, with little marketing.16

Most importantly, as Kyle successfully applied the transformation process repeatedly to more initiatives (specifically, those described at the beginning of this chapter), Lowe’s began to transform itself. The ossified operator of the past was quickly becoming an agile competitor that could dream bigger, execute on those dreams, and create its own future. It has since evolved from a home improvement retailer to a purpose-driven, home improvement technology company, officially changing its designation with shareholders and moving into spaces no one would have imagined years ago.

In addition to AR, exosuits, 3-D printing, imaging services, and robots, Lowe’s is redefining the idea of stores, home improvement, and home building. For example, could a store be a hybrid between your physical home and a virtual store? Could a store be mobile only? In terms of what home improvement means, could managing apartments be home improvement? Could education be part of home improvement, too? And, for example, could home building products be made directly from recycled materials brought by customers, and could materials be printed onsite instead of shipped from stores?17 Lowe’s teams are energized by their opportunities. In short, Lowe’s is undergoing a major transformation to become the kind of company ready for the future. Whether its transformation continues will depend, in part, on applying the ideas described in this book.

The Research Foundations of This Book: A New Behavioral Science of Transformation

This book begins differently than do most books. Although all three authors have PhD training and their recommendations are based on three decades of behavioral research, the book is not an academic’s perspective on how to lead change. Instead, the book describes what worked in real organizations to create change and how to repeat it. Thus, our goal is not to create an A-to-Z encyclopedia, a comprehensive handbook of transformation. Nor do we report on the research on transformation. Instead, we hope to give you access to the tools to lead a transformation. We also aim to start a conversation about the new or redesigned tools that are based on behavioral science and that will allow us to finally break through the human barriers to better futures.

To develop the tools we describe here, we drew on the established research, and our own research, across multiple related disciplines. Specifically, we took insights from behavioral economics, psychology, social psychology, applied neuroscience, and innovation.a In drawing on these domains, instead of rattling off lists of issues, biases, and limitation (the behavioral sciences alone have identified hundreds of biases and forces affecting our behavior), we focused on the critical behavioral traps we see in the real world—the fear, habits, politics, and incremental thinking that hold organizations back from doing what they say they will do. For example, when we talk about incremental thinking and how to overcome it, we are considering all the literature from psychology (e.g., confirmation bias, relatedness bias, and anchoring), neuroscience (e.g., neural responses to risk and uncertainty and neural mechanisms of creativity), and innovation (e.g., incremental innovation and ideation).

In light of this research (including our own contributions to these fields), we conducted additional research directly related to the ideas in the book. For example, we examined the Global 500 companies and their stated missions to understand if and how they use any form of narrative, as described in the book. We also conducted studies on other topics in this book, such as how to generate a greater number of novel ideas, how stories influence persuasion, and which media are the most persuasive. Finally, we designed and tested the tools in the book. For example, Thomas is perhaps the world’s foremost expert on neuroprototyping (i.e., the use of applied neuroscience tools to understand how people respond at a neural level to new products), having developed some of the most relevant applications of neuroscience to innovation and transformation problems.

But instead of reporting these studies as a listicle of findings, we acknowledge this research and then focus on how to use the tools developed to lead transformation. Although some of the names and situations are disguised to protect identities, we describe tools that we have tested and used in real organizations to overcome the common barriers to transformation. We openly acknowledge that these tools are not fail-proof, comprehensive, or relevant to every situation. No tools are. Instead, they simply address the behavioral traps we have identified as the most challenging, and they have worked for us.

Throughout the book, various endnotes cite the research underlying these tools, and sidebars dig deeper into the relevant research and mechanisms. A list of foundational readings is also included at the end of the book. The “Digital Toolbox” sections in each chapter present an online repository of tools, templates, and training that you can use or develop to fit your situation as you apply these ideas in your own organization.

Finally, the opportunities to further develop the science of transformation are also the reason we are creating the Transformation Lab, an interdisciplinary center to explore and design the tools we need to navigate the future. Because of the exponential growth in computing power, we are entering an era of unprecedented change and uncertainty. Many of the tools designed for a previous era of relative organizational and economic stability, an era of coordination and control, will fail in the era of uncertainty, which requires adaptation and change. The Transformation Lab is dedicated to discovering, encouraging, redesigning, and sharing the theories, frameworks, processes, and tools for a world of uncertainty.

This book is the first step in the effort to shape this new body of work.

a. For behavioral economics, psychology, and social psychology, see Dan Ariely, Predictably Irrational: The Hidden Forces That Shape Our Decisions (New York: HarperCollins, 2009); Daniel Kahneman, Thinking, Fast and Slow (New York: Macmillan, 2011); Richard H. Thaler, Misbehaving: The Making of Behavioral Economics (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2016); and Lee Ross and Richard Nisbett, The Person and the Situation: Perspectives of Social Psychology (London: Pinter and Martin, 2011). For applied neuroscience, see Joseph LeDoux, The Emotional Brain: The Mysterious Underpinnings of Emotional Life (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1998); Antonio Damasio, Descartes’ Error: Emotion, Reason, and the Human Brain (New York: Penguin, 2005), for summaries; and Eric R. Kandel, ed., Principles of Neuroscience, 5th ed. (New York: McGraw-Hill Education/Medical, 2012). For innovation, see Nathan Furr and Jeffrey H. Dyer, The Innovator’s Method: Bringing the Lean Startup into Your Organization (Boston: Harvard Business Review Press, 2014); Jeffrey H. Dyer, Hal Gregersen, and Clayton M. Christensen, The Innovator’s DNA: Mastering the Five Skills of Disruptive Innovators (Boston: Harvard Business Review Press, 2011); and Clayton M. Christensen, The Innovator’s Dilemma: When New Technologies Cause Great Firms to Fail (Boston: Harvard Business Review Press, 2016).

Each technological and behavioral change was the outcome of a process that Kyle applied over and over to effect a true transformation at Lowe’s. In that fateful meeting with Lowe’s executives, when Kyle showed them the comic book, the executives (and Lowe’s) were transformed. Kyle had applied the transformation process to create a bigger vision for the future and then to build that future. This transformation process invited resisters to jump on board and allowed the organization to suspend disbelief long enough to make a change.

The transformation did not result from an overarching mandate to change, followed by a roster of initiatives executed with militaristic force. Instead, the transformation occurred through the repetition of the process described in this book, building up the organization’s confidence and capabilities until, through many small-t transformations, Lowe’s made a big-T transformation. The core of the business continues to grow, and Lowe’s is ready for the future. Although technology played a role in Lowe’s transformation, it does not play a role in every transformation, and it is not the main character of the story. Instead, the real crux of the transformation depended on something much more common and fundamental: a set of tools to overcome the common behavioral barriers to transformation.

The Transformation Process: Three Steps to Take Charge of Your Company’s Future

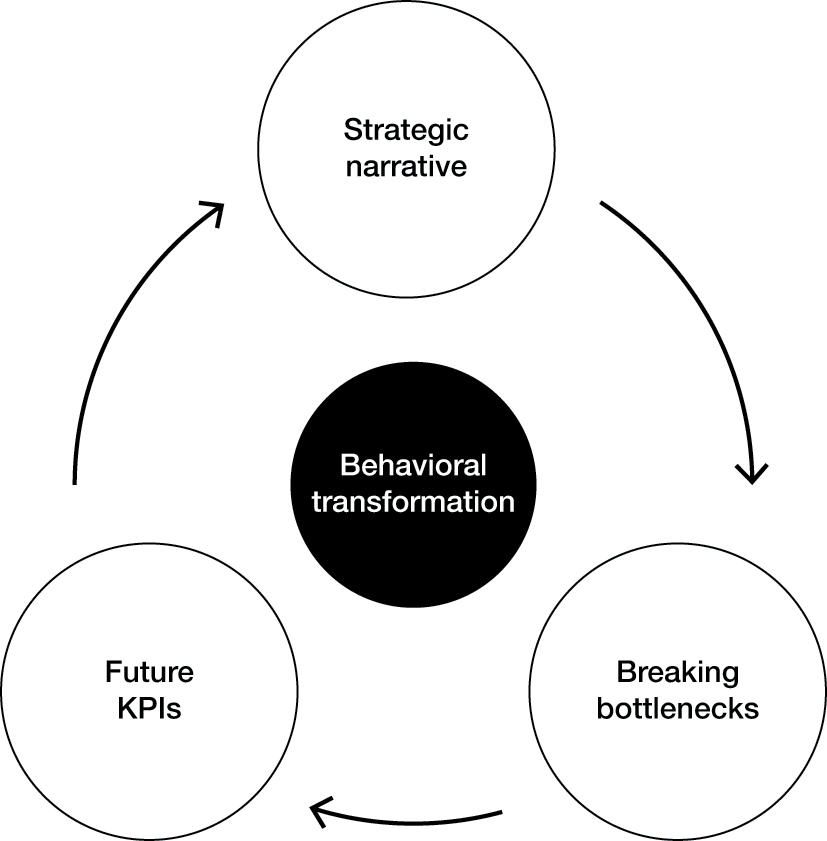

The process we describe for tackling some of the most difficult human limitations to transformation has three steps, all of which are based on behavioral science (e.g., psychology and neuroscience) (figure 1-1). Great transformers from the past—people who understood intuitively how to apply these ideas—often used these tools or elements of them. We simply describe the tools more concretely and how to use them.

Envisioning the Future: Using Science Fiction and Strategic Narrative

One of the biggest limitations to creating the future is the human tendency toward narrow thinking, or seeing only incremental improvements to the status quo. In contrast, we admire innovators like Elon Musk or Jeff Bezos precisely because they dream bigger, dare bigger, and then inspire those around them to change the world. When we interviewed Musk and his team at Tesla, what surprised us most was how Musk’s vision to change the world to a renewable, electric vehicle future had infected everyone at the company. Common engineers, assembly-line workers, and even custodians truly believe they are changing the world, not just making cars. One leader told us confidentially, “We don’t have the best engineers in the world, but they believe in what we are doing so much, we can do amazing things with them.” How can we do the same thing in the organizations we lead? How can we break free of incrementalism, dream bigger, and inspire people to follow us?

Leading transformation: three interrelated and iterative steps

Note: KPIs, key performance indicators

Our framework begins with a strategic narrative about a possible future. The narrative’s content and structure inspires people, dispels disbelief, and compels transformation. Before you dismiss this step as old news, consider that although business leaders talk about stories in big organizations, most leaders really have no clue about how to use them properly. In our analysis of Global 500 companies, less than 10 percent of companies appeared to have any meaningful story, and fewer used it well. But stories are one of humankind’s oldest and most powerful tools. Since the time when we humans gathered around the fire (and still do), stories have opened our eyes to what is possible, suspended our disbelief, and stirred our hearts into action. The power of story has its roots in evolutionary psychology: recent neuroscience research reveals that stories release a rush of neurochemicals that can literally sync people’s brains with one another and motivate action.18 When used properly, a story can help people see the future and can transform them from adversaries into advocates working hard to create that future.

In our transformation process, we focus on constructing strategic narratives based on a radical reenvisioning of what is possible. We use tools like speculative fiction to help us break the bonds of incrementalism and then to create a narrative that truly motivates and inspires those around us. The resulting story involves a protagonist, a dilemma, and a resolution, all built into a narrative arc that gives us reason to believe. We then find a compelling way of telling the story—a dramatic medium such as comics, videos, or even hip-hop (figure 1-2). Ultimately, what matters is finding a way of storytelling that overcomes your audience’s natural resistance. Our research reveals that the visual format often helps people suspend their critical mind and engage with the emotion of the story. In chapter 2, we will show you how to create a story that can inspire commitment and change necessary to take charge of your future.

Breaking Bottlenecks: Using Decision Maps and Archetypes

We aren’t the first people to talk about telling a powerful story (although we may be the first to use science fiction writers and comic books in the C-suite), but many people who have created stories have still wrecked on the rocks of routine. Developing the story may be the easier part. Navigating the rat’s nest of motivations, politics, and routines in any big company may be the hardest part. Few statistics exist to reveal how many initiatives are derailed by the decision bottlenecks in an organization, but in a recent survey, 72 percent of senior executives believed that bad strategic decisions were as frequent as, or more frequent than, good decisions in their organizations.19

There is no simple formula to overcome these challenges, but by applying tools rooted in behavioral science, you can find better ways to identify and break the bottlenecks. These tools are the focus of chapter 3. To start breaking these bottlenecks, we begin by asking a simple question: what kind of organization do you work in? This often-unasked question reveals deep insights about what the organization values and the organization’s dominant nomenclature, or language, required to communicate and get things done. Then we map out the informal and formal decision process by creating a decision bottleneck map. Next we identify the individual archetypes—the primary roles that decision makers play—and where they sit in the key decision holdups. Using this critical information, we can look at the organization’s habits and use them as bottleneck breakers to facilitate a transformation.

We’ll describe several common habits of organizations, but one of the most underappreciated involves a company’s tendency to overlook abundance. For example, Lowe’s initially overlooked the value of the millions of customers walking into its stores wanting to learn—the ideal environment for experimenting with new technologies. But through our guidance, Lowe’s learned to recognize the value of this abundance and turn it into a currency to attract some of the world’s leading partners, such as Microsoft and Google.

Navigating the Unknown: Using Applied Neuroscience and Future Key Performance Indicators (fKPIs)

Doing something new, whether it be transformation or innovation, almost always creates fear and resistance. Voltaire, the French philosopher, once wrote, “Our wretched species is so made that those who walk on the well-trodden path always throw stones at those who are showing a new road.”20 In addition to encountering resistance from others, when you pioneer into new territory, you rarely see many signposts that you are heading in the right direction. You are the one blazing the trail. Thus, you have few data points to reinforce your own confidence that you are on the right track.

To overcome the fear that accompanies doing something new, you need data-driven indicators that you are on course, both to guide your choices and to create confidence among those you lead. Unfortunately, most of the measurement tools available are built to assess past performance and so are unreliable indicators of an uncertain future. For example, tools like focus groups or customer feedback can be notoriously dangerous when you are designing new-to-the-world products. Gianfranco Zaccai, who developed the Aeron chair, the Reebok Pump, and the Swiffer, used to say, “I’ve never seen innovation come out of a focus group.”21

To move into the future, we need new tools and measures to accurately understand what direction to go. Chapter 4 shows how to use artifact trails, experimental design, and data-driven indicators to obtain signposts as you break new territory. You also learn how to create confidence in those around you so that they are inspired to join you. Specifically, we start by identifying the end goal, then work backward to define an artifact trail—the series of small, observable activities and prototypes that can act as small wins to keep enthusiasm high. We then define the future key performance indicators (fKPIs, where the lowercase f represents the function of how you create the future) and the experimental design needed to reliably generate defensible measures of the direction you are going. Typically, we use a tool like the experimental design canvas, described in the book, to choose the fKPIs needed to navigate the future. Then we apply the best tools we can find to generate these fKPIs.

Our favorite tool, and perhaps the most valuable one, to navigate the unknown is applied neuroscience. This tool generates data that can reveal what people don’t even know about themselves. To use applied neuroscience for transformation, we used four research-based measures—engagement, emotion, overload, and attention—which we correlate to actual behaviors to predict the best path forward.22 We compiled this data to help Lowe’s choose between mixed reality, VR, and AR—and the decision helped the company collaborate in the launch of one of the first commercially available AR phones, which we described earlier. Although neuroscience may be the Ferrari of experimental design tools and remarkably inexpensive when sourced from a reliable vendor, the key is not the neuroscience. Instead, the focus is on designing new fKPIs to overcome fear and give you the confidence to move into the future.

Taking Charge of Your Future

In this book, we describe some of the many possible tools for leading transformation by addressing the ultimate bottleneck, the human element of transformation. Don’t be confused by the technologies, the science fiction, or the comics. What we care about is behavior change. We have applied these same ideas at companies like Pepsi, where there was little technology involved—just transformation. Similarly, we applied the tools at Svensk Film, to help it explore how to transform itself from a film company that owns cinemas and produces movies to a company that creates experiences and inspires passion, an emotion the company can now objectively measure using applied neuroscience and use as a guide on its journey. Ultimately, the transformation process is designed to help people overcome the incrementalism, routine, and fear that holds back transformation. To help you apply the transformation process, we will describe how to create strategic narratives, break bottlenecks, and create fKPIs that allow you to chart a real path to an exciting future. We will also emphasize the Trojan horse approach to transformation: rather than attacking transformation head-on, we propose that you create many small, realizable transformations that will add up to a major transformation—the same way that Lowe’s built up many small-t changes that ultimately added up to a big-T transformation.

We recognize that the approach in this book isn’t the only road to transformation and that we don’t describe all the available tools. We welcome the addition of new tools, of which there will be many more. All of us are at the beginning of a conversation, not at the end of it. Many of you will no doubt develop even better tools to address the behavioral limitations described here or new tools to address the barriers we have not addressed.

In closing, we are certain of one thing: the future, as a fixed destination to be reached at some impending date, does not actually exist. Although you may pay smart consultants to help you understand that future, they can’t tell you what it will be either, because no one knows the future. They can’t know the future, because there is no predetermined future out there other than the one you create!

Ultimately, this book is about recognizing this simple idea: that you can envision the future you want to create, and then by working with these tools, in collaboration with uncommon partners, you can take charge of the future for your organization. Of course, there are constraints. You cannot wave a magic wand. But the future only happens when someone takes action and creates it. If we learn one thing from innovators like Musk, Bezos, or Jobs, it’s that they had the gumption to create the future they imagined. So if someone is going to create the future, why not you? You can take charge of your future and shape it in the direction you hope it will go.

As more of us realize this point, the future will become ever more dynamic. For those who are trying to hide in the old, walled gardens of supposed competitive advantage, this new approach will feel like a threat and will create unbearable uncertainty. But uncertainty is only one side of the coin—the side we see when others seem to be changing the world in which we live. The other side of the coin is possibility—the possibility that as the barriers to participate, create, and interact come down, the possible new futures we can create together will only increase. This book is about taking charge of your future.