Caecina and Valens

Early on 2 January Vitellius sent messengers from his headquarters at Cologne to the four legionary commanders of Lower Germany at Bonn, Neuss and Vetera, reporting the mutinous attitude of the Fourth and Twenty-Second Legions at Mainz communicated to him late on the previous evening. He put it to his lieutenants that they must either fight the rebels and remain faithful to their oath of loyalty to Galba, or, if the unity of the forces in Germany was thought worth preservation, nominate their own emperor. Prompt choice of a ruler, he added, would be safer than a prolonged search for one.

This well-weighed and diplomatically-phrased dispatch earned an immediate and enthusiastic response. At midday the commander of the First Legion, stationed at Bonn only twenty miles away, entered the walled city of Cologne at the head of his legionary and auxiliary cavalry, made his way to the governor’s palace on the bank of the Rhine, and hailed Aulus Vitellius as Imperator. Vitellius accepted the acclamation and was carried in procession through the busiest streets of the city, holding a drawn sword, allegedly that of Julius Caesar, which someone had taken from the Temple of Mars and thrust into his hand.

In offering Vitellius the purple, the hard-headed and unscrupulous Fabius Valens must have known that his action would not be unwelcome. This in turn implies prior discussions between Vitellius and the two officers who were to be his marshals, Caecina and Valens, and the speed with which the movements gathered way points in the same direction. The lead offered was eagerly followed by Fabius Fabullus and Munius Lupercus, commanding respectively the Fifth and Fifteenth Legions stationed at Vetera, and by Numisius Rufus of the Sixteenth at Neuss. On the third day of January the Mainz garrison dropped its protestation of loyalty to the Senate and People of Rome and recognized Vitellius as emperor; and in due course the adherence of the outlying Twenty-First at Windisch was confirmed.

It is not difficult to reconstruct the considerations that induced Vitellius to accept this dangerous eminence. Some rational and not entirely selfish calculations may be attributed to him. If Galba on the strength of the acclamations of a single legion believed—and rightly believed—that he had a duty and a capacity to replace Nero, might not similar confidence and a similar duty be felt by the chosen candidate of seven legions ? Legionaries were after all Roman citizens, spokesmen of the community at least as qualified to speak as the mob of Rome or even the Praetorians. There were not many places outside Italy, and few within it outside Rome, where it was possible for 35,000 Roman citizens to voice any, let alone a united, opinion. If ancestry were still a criterion of fitness to rule, Vitellius could point to a father who had achieved in the reigns of Tiberius and Claudius the high distinction of three consulships; and as consul in 48 and governor of Africa thereafter, he could at the age of fifty-four look back to a career if not of distinction yet of moderate success. He felt himself to be popular with his men, and he was undoubtedly easy-going, unpretentious, open-handed. Without vaulting ambition, he was willing to accept a leadership strongly pressed upon him by his subordinates. In any event Galba could not last long, and his death looked like bringing a new coup d’état. If the armed forces serving outside Italy were now to appoint their commander-in-chief, no army group had a better right to nominate one than that of the Rhine.

The attitude of the legionaries was more positive and self-interested.* Though recruited primarily from Italy and highly Romanized areas, they had acquired from long service in one place a cohesion among themselves and a sort of local loyalty. A soldier had two countries: Italy and his camp. In theory and in law Roman legions were subordinate to their commander-in-chief, the emperor acting as the executive arm of the Roman Senate and People. They could be moved from one part of the wide empire to the other as he decided. In fact, none of the formations then under the command of Flaccus and Vitellius had been in Germany for less than twenty-eight years, and one—the Fifteenth—had occupied the same headquarters for fifty-nine years. As the term of legionary service was of twenty years, this implies—all allowance made for cross-postings—that many of the men, young and old, had served all their lives in the same legion and the same area of Germany. They had formed local attachments of every kind. But the policy of Galba, who had already moved the Tenth Legion from Pannonia to Spain after a stay of only five years, might well herald a threat to this comfortable immobility. Indeed common prudence was bound to suggest to Galba that troops prepared to make an emperor of Verginius Rufus should not be allowed a second chance of demonstrating their power: the legions in Germany were faced with the near certainty that the friend of Vindex would gradually avenge him by scattering them to the four corners of the world. If, however, Vitellius were to become emperor at the cost of a walk to Rome, there would be prospects of pickings—promotion, for example, to the Praetorian Guard at vastly greater rates of pay; or failing this, the assurance of returning to one’s old locality under an easy master. And the local population of civilians, among whom time-expired veterans formed a noticeable element in the garrison towns, were equally enthusiastic for Vitellius; the Treviri and the Lingones, Galba’s victims, equally friendly.

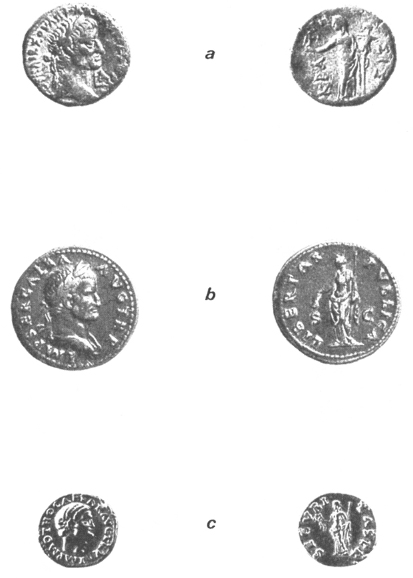

The enthusiasm translated itself into practical forms. Both troops and civilians offered contributions to the cause, the former their savings lying in the military chests of the legions, their sword-belts, medals and silver parade equipment; the latter money, equipment, horses. The metal was used to mint a coinage which we may plausibly identify with the so-called military issues of 69—coins showing, for instance, clasped hands symbolizing union and loyalty with the hopeful legend FIDES EXERCITVVM or the even more buoyant FIDES PRAETORIANORVM,, but containing no mention of Vitellius, whose constitutional scruples apparently forbade the assumption upon the coinage of the recognition of the Senate and People of Rome formally to be accorded to him in April. But the troops gave him the title ‘Germanicus’, something less than an imperial one, yet with happy associations. (It was of the type applied to the commander successful in a military campaign on the frontier, like ‘Africanus’ or ‘Dacicus’, though there had been no campaign as yet.) ‘Augustus’ he was less anxious to assume, and ‘Caesar’ he became only in the last desperate days of his reign.18

A strategy was quickly formulated, or revealed. While token forces were left in the headquarters establishments along the Rhine, something between a third and a half of the legionary strength, plus a large number of auxiliary units of infantry and cavalry, were to move on Rome and displace Galba—or, as it was soon known, Otho. The need to maintain and strengthen communication between the Rhine and Rome, the difficulty of feeding large numbers of marching men and the strategy of invasion dictated a two-pronged advance. One would be led by Caecina, the other by Valens, with units drawn respectively from the Upper and Lower Military Districts. In due course Vitellius would follow with the remainder of the forces available.

The prospects for the campaign were good. The governors of Britain, of Belgian and Central Gaul, and of Raetia declared their adherence. The first of these provinces provided drafts of legionaries. Thus Spain with its single legion—the Sixth, the formation which had acclaimed Galba in April 68—presented only a slight threat. A key legionary garrison, that of Pannonia, nearest to Italy, seemed no problem, for L. Tampius Flavianus, its governor, was a relative of Vitellius. In Syria Mucianus was hardly a military menace, and had little in common with Vespasian in Judaea, himself tied down by the Jewish War. In Italy itself there was a hotch-potch of fragmented forces, none deeply attached to Galba. Apart from this, the Roman legionary order of battle comprised only the three formations widely spaced along the lower Danube against a continual threat of incursion from the north, two legions in far-off Egypt, and a single one in the province of Africa. Vitellius seemed to himself to dispose of an overwhelming military superiority. Nevertheless, it was decided to strike at once and to begin the long march southwards in order to cross the Alps at the earliest possible opportunity.

Fabius Valens was to take the longer route from the Rhineland via Lyon to the Mt Genèvre Pass, which, though not the lowest of the Alpine passes, is comparatively sheltered and easy. Its choice might well surprise an enemy guarding against an invasion which in the winter months seemed most probable by the easiest route of all, the Ligurian coast road. Caecina was allotted the shorter but much more strenuous passage by the Great St Bernard, which in any event would have to be controlled sooner or later since in summer it provided the quickest communication between Rome and Rhine. The two forces could effect a junction at Pavia or Milan. The exact numerical strengths of these forces it is difficult to determine. Tacitus’ account, not readily explicable on our information, assigns to Valens about 40,000 men and to Caecina 30,000. Both figures are probably exaggerated and look suspiciously like an approximate estimate of the total strength of the Rhine garrisons: 5,000 to a legion, with auxiliaries roughly as numerous. But Vitellius did not contemplate stripping the long and vital Rhine frontier of all its troops. On the other hand we may accept the historian’s statement that Valens received drafts of legionaries drawn from the formations of the Lower District, together with the main body of the Fifth at Vetera and with auxiliary cavalry; to Caecina was given the Twenty-First from Windisch together with corresponding supporting troops. Each commander was also to be allotted some of the amphibious Batavian cavalry skilled in crossing their native and all other rivers, and with them a few German cohorts recruited east of the Rhine and possessing similar training. After all it might be necessary to force a defended Po.

A fortnight’s hard staff work enabled both commanders to be on the road by the second half of January. Valens’ route lay through Trier, the capital of the friendly Treviri. At Metz their neighbours the Mediomatrici were predictably less friendly, and though the townsfolk showed every civility to a dangerous guest, the nervous troops were involved in a panicky outbreak which hostile propaganda alleged to have cost 4,000 lives. After this—whatever the true figure—the provincials were so alarmed that on the approach of the marching column (as later at Vienne, under suspicion for its connection with Vindex) whole communities went out to meet the Vitellian force with white flags and pleas for mercy. Women and children prostrated themselves along the highways, and every conceivable concession was made which could speed the irascible visitor upon his way.19

News of Galba’s assassination and Otho’s accession reached Valens about 23 January, when he was at Toul. The information signified little, except that the Vitellians now had the moral advantage of confronting an adversary whose title to empire was considerably worse than their own. For the Gauls, and indeed for the Roman world at large, the future seemed even more sinister and unpredictable than it was already: the Vitellians were not turning back.

At Langres the army was joined by a portion of the eight Batavian cohorts, others travelling via Besançon to reinforce Caecina’s men; what the local Lingones chiefly remembered afterwards was a squabble between the Batavians and the legionaries, typical of many. At Chalon-sur-Saône one reached the valley of that river, and at its confluence with the Rhone lay the capital of the Three Gauls, Lyon. The city offered the warm welcome to be expected. The First (Italian) Legion, commanded by Manlius Valens and consisting of Italians six-foot tall—chosen by Nero and given the grandiose title of ‘The Phalanx of Alexander the Great’—and an auxiliary cavalry regiment were pressed into Fabius Valens’ service, though the Eighteenth (Urban) Cohort was left at Lyon, where it was normally stationed to police the largest city on the west. Vienne, on the other hand, paid for its past activities by losing its right to possess a local militia and by handing out heavy protection money to Valens. At Luc-en-Diois, in the Drôme valley, it is alleged that he threatened to set fire to the town, one of the two capitals of the Vocontii, unless the tribute demanded was paid.

The long catalogue of woes may be plausibly attributed to stories retailed to Pliny the Elder, an important source for Tacitus and others. In 70, when he was perhaps an imperial agent in Gaul, one can well imagine the eagerness with which local magnates would have apprised a financial official of the havoc they had suffered at the hands of a faction against which Pliny’s master Vespasian had rebelled and, equally well, the ready credence given by that official to allegations providing most acceptable propaganda material.

At Gap, in early March, it was necessary to detach some 2,600 men to meet an Othonian naval invasion of the Ligurian coast. In the latter part of the month Valens and his army were crossing the Mt Genèvre into Italy (the winter was mild, or spring early), and at its end they were in Turin. The march had gone well. A truculent attitude and a good choice of time and route had secured them an uninterrupted passage. Otho’s maritime expedition had had little influence upon the advance, and though the detachment diverted to deal with it had been largely unsuccessful and a cry tor further help met Valens at Pavia, he refused to fritter away any more men on what proved in the end a blind alley. Indeed his troops wanted no diminution of their strength now that they were almost in sight of the enemy.

Caecina’s progress was more strenuous. In the first half of January he left Mainz in advance of his troops, and travelling on horseback up the bank of the Rhine arrived at the low plateau near the confluence of the Aare and the Reuss, upon which lay the permanent camp of the Twenty-First Legion at Windisch near Brugg in the Aargau. The situation he found there was one of some confusion, and he was faced by a task involving more than a winter crossing of the Alps.

The fortress lies towards the north-east end of the long and wide strath that runs from the Lake of Genèva to that of Constance between the Jura and the Bernese Oberland. This corridor leading from the Rhineland to Italy was inhabited by the Helvetians, once famous as a populous warrior-tribe whose emigrants had presented a severe challenge to Julius Caesar 126 years before as he trailed them to central France and fought hard with them in the Saône-et-Loire. In 69 they had long enjoyed the benefits of the Roman peace, and their industry, productive soil and position upon a main highway of travel and trade had brought a prosperity destined soon to be increased under the Flavian régime. As a gesture to their warlike past, the Romans allowed them the privilege—it was not an onerous one—of manning some of the forts along the Rhine towards Baden. Of these Zurzach was one of the most important. The garrisons of these forts were raised and paid by the Helvetians and formed no part of the regular Roman army: honour was satisfied and money saved.

The events of these days are narrated by Tacitus in some detail. No less than three prominent Helvetians are named. This attentiveness is explicable by the use of Flavian sources concerned to honour the régime. In his later years, Vespasian’s father had carried on a banking business in the Helvetian capital Avenches, lured perhaps by developments associated with the conquest of Britain and the improvement of the Great St. Bernard route. Indeed, the future emperor, during his service in Upper Germany and Britain, may have left his infant son Titus to be brought up at Avenches near his grandfather. At any rate, an inscription survives there, a dedication to a lady described as educatrici Augusti nostri. The grant of the title of colonia and the upsurge of building in Flavian times seem to attest imperial favour and a desire to offer recompense for the hard days of early 69.20*

The trouble at Windisch initially involved an act of looting. The pay for the men garrisoning the Helvetian frontier forts was sent down at regular intervals from Avenches. The route followed by the paymasters crossed the bridge over the Aare that lay a little to the north-west of the legionary camp. Early in January, discipline being unsettled by the news from Cologne and Mainz, some rowdies of the Twenty-First held up the paymasters on their way and stole the pay. The Helvetians were not prepared to put up with this sort of treatment. Feelings ran high, and about a week later an opportunity for revenge occurred. Somewhere on the main road west or east of Windisch their militia arrested a centurion with a small escort of legionary soldiers: they were carrying an appeal for support from the Rhine armies to the garrison of Pannonia, east of Raetia and Noricum. This smelt like treason. The messengers were kept in confinement, perhaps in the hope of obtaining restitution for the loss of the money. Such tactics were not well advised, and the Helvetians were foolish to take a revenge which was not only of doubtful legality but presented a direct challenge to a powerful army.

The resulting tension that confronted Caecina as he arrived constituted a threat to his line of communications. He immediately moved out the Twenty-First Legion in an exercise of systematic devastation of the lowlands. This even included an attack on the nearby spa of Baden, which the troops knew well and which, in the sheltered valley of the lower Limmat, had developed from a village to a holiday town and watering-place where you could bathe and take the sulphur waters in the comfort and scenic beauties typical of this and all other spas. Archaeology reveals a burnt stratum attesting a conflagration, perhaps of this year. The Helvetians now sounded a general tocsin and called up men long unused to war. Caecina replied by summoning to his assistance auxiliary units stationed not far to the east in Raetia (probably at Bregenz), and caught the motley Helvetian levy between two fires. There seems to have been no set battle, but a series of skirmishes lacking all firm military direction by the inexperienced Helvetian leaders. The case was hopeless, and illustrates the nature of Roman imperialism: beneficial if you worked with it, and what else could you do ? Even if competent as soldiers, the people could not then have found refuge behind the long-disused and crumbling walls of the hill forts they had maintained before the Romans came. Towards the end of January, after a few days of chaos, the Helvetian conscripts threw away their arms and made for the fastnesses of the Mons Vocetius, sometimes—though without great probability—identified with the Bozberg between Basel and Brugg.* A cohort of Thracians was promptly ordered to drive them down from the height, and other auxiliaries, from Germany and Raetia, beat the forested area and killed the skulkers in their hiding-places. Casualties were heavy among the Helvetians.21

By the time this mopping up was completed, the drafts allotted from the Fourth and Twenty-Second Legions had arrived in Windisch from Mainz, and in the first week of February Caecina moved towards the Helvetian capital, eighty miles away, with a substantial army of some 9,000 legionaries and perhaps twice that number of auxiliaries. Further resistance was not to be contemplated. The Helvetian leaders sent out plenipotentiaries to negotiate a surrender. Despite the vigour of the repression, understandable without positing any particular venom on Caecina’s part, the Roman was sensible enough to avoid vindictive terms that might implant an enduring resentment and present a renewed peril. One Helvetian leader regarded as particularly responsible for the call to arms was executed forthwith. The fate of the rest was left to Vitellius, still at Cologne. A representative party of Helvetians were sent there under Roman escort. At the audience, the Rhineland troops breathed out fire and slaughter, and thrust their weapons and fists under the noses of the unfortunates. Even Vitellius made a show of verbal severity. But he was quite prepared to deal gently with them. In any case there were mitigating circumstances, and the Helvetians had already paid a heavy price for trying to ride the high horse. No further executions were exacted, nor did Avenches suffer.

It was about 23 February before the party returned from Cologne. Caecina had employed the interval in very necessary preparations for the rigours of an Alpine crossing made before the date at which the passes are normally open. Whether the higher parts of the Great St Bernard * route were or were not capable of taking wheeled traffic—in Augustus’ time they were not, and the evidence of Roman paving at the top may be later than A.D. 69—it would have been madness to rely upon the normal legionary transport. Horses and mules had to be requisitioned and the baggage of the waggons redistributed.22

Amid these preoccupations good news came to reward Caecina for his determination. A unit stationed in the Po valley had declared for Vitellius. It was the Silian cavalry regiment which had served in Africa during Vitellius’ popular period of office there as governor, had been earmarked by Nero for his Eastern campaign, sent to Alexandria and then recalled in view of the threat from Vindex in Gaul. At the moment it was marking time in the Eleventh Region of Italy, which contained the important towns of Milan, Novara, Ivrea and Vercelli. Towards 22 January the officers of this unit, on hearing first of the revolt of Vitellius and then of the death of Galba, had to decide their attitude to the usurper and assassin Otho. They were not acquainted with him personally, and finally decided that they preferred the devil whom they knew, perhaps also calculating that a timely change of front might win them considerable prizes in a contest in which the odds seemed heavily weighted in favour of Vitellius’ seven legions. These considerations they put to their men, who agreed. Some elements of the unit were sent to bring the news to Caecina and await instructions.

Caecina gave them a hearty welcome, and immediately sent off some auxiliary infantry from Gaul, Lusitania and Britain, as well as cavalry from Germany and the unit called the Petra’s Horse’ to consolidate the position in the Eleventh Region, where the turncoat regiment seems at this moment to have been the sole unit.

Less reassuring was the attitude of Noricum, where the pro-Othonian governor, Petronius Urbicus, had mustered his auxiliary forces and cut the bridges over the Inn at Innsbruck-Wilten and Rosenheim. It was clear that the Vitellians were not going to have it all their own way. Upon reflection Caecina decided that any attempt to deal with this danger from the flank—and after all Urbicus had no legions, and the cutting of the bridges was essentially a defensive act—must be postponed. The vital thing was to exploit the mild weather and the lucky situation in northern Italy.

Towards the end of February he set his heavy column in motion. The legionaries toiled up the long slopes from Martigny towards the promised land. The weather held, and the long ascent went without a hitch. Early in March Caecina stood in Italy: he had stolen the race from his rival and colleague Valens by almost four weeks and found himself master of the north-western portion of the Po valley, the storehouse of Italy, famous for its millet, pigs, wool, and wine stored in pitched jars larger than houses.23

The months of January and February, during which Valens and Caecina were known to be making their several ways towards northern Italy with the evident intention of displacing Otho, saw signs throughout the empire of the growing unease which sprang from the apparently inevitable return of civil war, the ultimate disaster which the principate was instituted to prevent. In Rome the foreboding was heightened by the feeling that the capital, above all other places, would lie at the mercy either of an Otho or of a Vitellius exasperated by war and elated by victory.

In the East similar, if less urgent, doubts and fears existed. Galba had been promptly recognized by Vespasian when the news of his accession reached Judaea in late June 68. Military operations against the Jews were suspended. In December, after notifying Galba of his intentions, he sent off his son Titus, now twenty-nine years old and a competent commander of the Fifteenth (Apollinarian) Legion in Judaea, to pay his respects to the new emperor in Rome, where it was known that Galba had finally arrived.

Titus was a man of charm and talent. Though short and tubby, he enjoyed good looks and great strength. He had an unusually retentive memory, and a capacity for learning all the skills of peace and war. He handled arms and rode a horse like an expert, and had a ready knack for composing poetry and speeches both in Latin and Greek, whether extempore or not. He was something of a musician, too, having a pleasant competence as a singer and harpist. A minor accomplishment was that he was good at shorthand: he had achieved a high speed and would compete with his secretaries for fun. He could imitate any man’s handwriting and often claimed that he might have made a first-rate forger. His affability and generosity are best illustrated by a dictum of his dating from the time when he was emperor: at dinner one evening he realized that he had conferred no favour in the last twelve hours and exclaimed, ‘My friends, I have wasted a day!’ Such varied talents and virtues could hardly fail to win admirers. On his December journey he was accompanied by one of them, King Agrippa II, ten years his senior, ruler of Golan and a large area east and north-east of the Sea of Galilee. Agrippa was a typical figure in the organization of Roman rule: a client-king, controlling a small border state with some degree of independent action, and suffered to keep his little court so long as he preserved order and maintained friendly relations with Rome. Agrippa had every inducement to hope that Titus would one day be emperor, or at least a member of the governing élite.

As it was winter they avoided the open sea and coasted along the southern flank of Anatolia in warships. Towards the end of January they had reached Corinth, where one transhipped to the western Gulf. Here they heard the disturbing news of Galba’s assassination and the near-certainty of an invasion of Italy by Vitellius. Titus reviewed the difficult position anxiously with Agrippa and some advisers. Finally he decided against putting himself in a false and possibly dangerous situation: he would return at speed to Vespasian for further consultation. Agrippa, however, continued on his way to the capital, where he remained the eyes and ears of the Flavians until secretly summoned home on the proclamation of Vespasian as emperor in July. He at any rate was safe enough in Rome under Otho: he had come in the irreproachable guise of a client-king, a friend and ally of the Roman people, owing allegiance to whatever emperor destiny—or the Roman people—should select.

Titus traversed once more the Aegean. But despite the need for speed he chose the easterly route, being determined to put in at Ephesus to discuss the situation with the local governor, C. Fonteius Agrippa.* The interview was encouraging: Anatolia was solidly behind a Flavian claim to empire. Then, sailing from cape to cape to make up time, he set course for Rhodes, and then with continuing good weather, risked a direct passage to Caesarea. This voyage meant a long open stint of 250 miles to western Cyprus (three days, probably, at sea with luck) and the 205 miles from Paphos to Caesarea. At Paphos he paid a quick visit to the famous Temple of Venus with its vast riches and strange aniconic cult emblem, a truncated cone. Titus did his duty as a sightseer and then asked the oracle of the shrine if the weather would hold and make a continuation of the direct passage possible. Yes, it seemed it would. Then, offering a more lavish sacrifice, he enquired of his own future in veiled language: ‘Shall I succeed in what I am hoping and planning?’ The priest Sostratus was discreet and well-informed. The omens offered by the livers were favourable: but would Titus be pleased to see him in private? The two conferred, and Titus emerged from the interview reassured and confident. What kind of optimism this was we can guess, but at least the open crossing was performed without incident. When he reached Caesarea, the Roman capital of Judaea, he found that the armies of Syria and Judaea had recognized Otho as emperor.

The purpose and implications of Titus’ journey have been long debated. The account survives in a number of allusions; and the fullest version, that of Tacitus, is, as usual, the best. But even his account is obscure in some particulars, and the abortive trip seems hardly worth a mention. But it must have figured prominently in the accounts of the Flavian historians, no doubt because it seemed to demonstrate the loyalty of Vespasian and his faction to the last respectable emperor, Galba, and perhaps hinted that they were the chosen instruments of a mysterious providence revealing its purposes soon after Galba’s death. But we are entitled to ask whether it was really necessary for Vespasian to send his son—admittedly in a lull in the fighting—on a potentially dangerous winter voyage merely to pay personally those respects which he must have offered to Galba in Spain months before by letter. A second reason is produced by Tacitus: Titus was of the right age to seek office—an illusion to the fact that on 30 December 68 he had completed his twenty-ninth year, and could consequently hold the praetorship.* It was quite legitimate for army officers serving abroad to return to Rome with their general’s permission to sue for civil offices. Titus could therefore plead this as a publicly acceptable reason for the journey. But the fundamental cause must be sought in the rumours of an impending adoption which developed in Rome after Galba’s arrival and which could have reached the ears of Vespasian by December. Certainly, as Titus travelled westwards, public opinion on his route believed that here was a possible heir for Galba. Crowds met him at his landfalls. Clearly, one should be polite to a potential emperor. After this, the sudden disappointment of Corinth must have been a considerable blow even to a sanguine nature accustomed to easy success. He could expect no gratitude either from Otho or from Vitellius for a journey ostensibly undertaken in the first place as a tribute to Galba; and it might be dangerous to put himself as a hostage into the hands of the new master, whoever he was to be.

If the reasons for the journey, and its commemoration, are not quite clear, Titus’ second enquiry of the oracle makes us wonder whether he was already contemplating the possibility of a Flavian bid for the principate. If this were so, it would explode the claim advanced by some of the Flavian historians that only in June did Vespasian reluctantly accede to the pressures of his followers. No clear answer to this problem is possible. Under Nero prominence was dangerous. Since the death of Corbulo at Nero’s jealous insistence in October 66—shortly before Vespasian’s appointment to Judaea in February 67—every important governor and commander must have felt himself to be balancing on a knife-edge. In such years inactivity was a virtue, as Galba had believed. But a man charged with repressing a Jewish insurrection could hardly be inactive. Unless the campaign—incredibly—failed, success must bring danger. The war must not be prosecuted too quickly. Nevertheless, Vespasian’s reputation grew steadily. The initial jealousies between the governors of Judaea and Syria soon turned to consultation and mutual confidence. In this process Titus was credited with a considerable part, and already in October 67 he had paid a visit to Mucianus, though we know nothing of the motive for it. From July 68 onwards a degree of positive collaboration was achieved, which, since it was not disloyal to Galba, must have envisaged the day, surely not far distant, when his successor would be chosen. It is therefore likely that in February or March 69, on the return of Titus to Judaea, the fears and ambitions of the Flavian faction had crystallized into a decision to await the outcome of the imminent conflict between Otho and Vitellius, with possibly some forward planning for either of the two possibilities: the defeat of Otho, the defeat of Valens and Caecina. Only with the news of the First Battle of Cremona at the end of April could firm decisions be taken; and these were based on the interaction of the attitudes of the legionaries and of the Flavian leaders. These attitudes seem broadly to have coincided: Vitellius and his people were incompetent and intolerable; and the chances of a successful Flavian intervention were manifestly good. It was not possible for contemporary Roman historians to write a detailed account of these transactions unless the confidential memoirs of Vespasian, Mucianus, Titus and Tiberius Alexander were accessible to them, which is highly unlikely, and we can hardly blame Tacitus if, writing thirty years after the events, he leaves many things in obscurity. With a good deal of obscurity we must ourselves be content. Only one thing is certain: the final decision of Vespasian to claim the empire was not taken until May or June 69.

Some alarm was caused by the appearance of the first in a series of false Neros. Nero had died in a small villa four miles from Rome in circumstances not entirely clear, and since the Senate declared him a public enemy he cannot have received the honour of a state burial in the glare of publicity. In Greece his appearances at games and competitions in person in 67, eccentric and fantastic as they were, his declaration of the freedom of Greece, his attempt to dig a canal through the Isthmus of Corinth and his lavish concessions gave him a degree of publicity accorded to few, if any, of his predecessors. After June 68 rumours circulated that he was still alive. Pretenders claiming to be Nero arose in 68, in the reign of Titus and in 88, and three and a half centuries later St Augustine asserts that many people of his day thought that Nero never died, but that he lived on in the age and vigour in which he was supposed to have been slain, until the time should come when he would be revealed and restored to his kingdom. Such a depth of credulity explains the flutter of excitement surrounding the present impersonation. In the autumn of 68 Nonius Calpurnius Asprenas, appointed governor of Galatia and Pamphylia by Galba, who in uniting these two provinces reverted to Augustus’ arrangement which Claudius had abandoned, was proceeding with two triremes across the Aegean to Ephesus. He put in at Kythnos, a minor island of the Cyclades group famous chiefly for its cheeses and hot springs, but lying on the Athens-Delos route and used as a port of refuge in the not infrequent event, even in summer, of squally Aegean weather. While Asprenas was in harbour, the captains of his two ships were approached and invited to meet a man who claimed to be Nero. They agreed. There was certainly a facial resemblance, and the impostor shared Nero’s singing and lyre-playing abilities. In fact he appears to have been a slave from the Pontus, or, according to other versions, a freedman from Italy. From merchants’ slaves, deserters and soldiers on leave or posting, who happened to pass to and from the East, he had gathered a band of followers, some armed. There was talk of him in Corinth and Ephesus. His request to the trierarchs, made with a pathetic appeal to their ‘loyalty’, was that they should take him to Syria or Egypt. In their perplexity, the captains diplomatically replied that they would have to win over their men, and would return when all was ready. But they faithfully reported the whole story to Asprenas. The governor had no hesitations: whether the man was Nero or not, he must be got rid of. The unknown individual was killed at his orders, and the corpse, its head notable for its glance, hair and ferocious expression, was carried away by the party when they left for Ephesus, and from there sent to Rome. The removal of this claimant did not preclude a number of successors, and in Trajan’s reign Dio Chrysostom, and somewhat earlier the author of the Apocalypse seem to attest contemporary rumours concerning a surviving Nero.24

A more impressive story came from Moesia. In January, stimulated, if stimulus were necessary, by rumours of impending civil war in the empire, 9,000 wild and exulting horsemen of the Rhoxolani, an ever westward-pressing Sarmatian tribe now probably roaming the area north of the delta of the Danube, moved upstream, crossed the frozen river between Gigen and Svištov, and in a sudden incursion cut to pieces the local garrison of two auxiliary cohorts. After this easy victory the invaders loaded themselves with the loot for which they had come and prepared to re-cross the river. But now their luck turned. The early spring which facilitated Caecina’s crossing of the Great St Bernard melted the ice of the Danube. The snow turned to slush, the tracks became slippery and the furious gallop of the Rhoxolani declined to the pace of a plodding caravan. On a rainy day they were caught by the seasoned Third Legion, moving eastwards from its headquarters at Gigen. This formation could look back to many battle honours dating to the late republic, and a few years before had exchanged the burning suns of Syria for the bleak mountains of Armenia and a toughening-up under a hard commander, Corbulo. In 68 they had been transferred to the Danube area. Now, a few months after their arrival, they were to show that they knew how to cope with wintry conditions and the cavalry of the steppes. Moving swiftly they fell upon the encumbered barbarians. Pilum-discharge was followed by the sword, according to the drill-book. The mass of the Sarmatians had little or no defensive armour, for they relied on their horses’ speed; and the chiefs, though formidable in the charge with lances and enormous four-foot-long swords, double-handed and twice the length of the Roman weapon, were helpless when bogged down and dismounted: they floundered about like rhinoceroses in cuirasses of iron-plating or toughened leather far more cumbrous than the flexible loricae segmentatae of the Romans. Most of the enemy succumbed to this well-executed assault, a few made their escape to the Dobrogea and the Delta, where they perished of their wounds or of damp and exposure.

PLATE 1 Coins of Galba (a and b) and Otho (c)

PLATE 2 Coins of Vitellius (a, b and c) and Vespasian (d)

This was the kind of police action continually demanded of the defenders of the southern bank of the Danube, but it had been conducted with exemplary speed and effectiveness. By the second half of February all was over. When the news reached Rome, Otho distributed handsome awards to the governor of Moesia, Marcus Aponius Saturninus, and all the three legionary commanders. There was an element of bribery in this; but if Aponius’ statue in triumphal guise set up in the hemicycle of the Forum of Augustus was cheaply acquired, Aurelius Fulvus, the commander of the Third, certainly deserved the award of an ivory ceremonial stool and the right to wear an embroidered toga. In any case, the victory delighted Otho, and though he had no part in it personally, it seemed to give him an added prestige. On i March, when according to an immemorial annual custom the Vestal Virgins renewed the sacred fire that symbolized Rome’s eternity, a laurel wreath was placed over the palace entrance in a ceremony itself commemorated by the assiduous Brethren of the Fields, led by their vice-president, Otho’s brother Titianus. Such lavish self-congratulation seems to betray a lack of confidence, but the necessity for the operation demonstrated the importance of the watch on the Danube.

In Corsica the governor Decumus Picarius rashly declared for Vitellius and was at first followed by the ignorant and sheep-like populace, especially after he executed two Romans (one a naval officer) who had disagreed with this venture. But when the natives discovered that the governor’s new allegiance involved their own conscription and military training, it became less popular. A conspiracy was formed and the governor was assassinated when helpless—in the bath. His immediate staff were also disposed of. Their heads, like those of outlaws or false Neros, were taken to Rome by the conspirators in person, optimistically hoping for a reward. But they got neither thanks from Otho nor punishment from Vitellius, neither of whom had the time or inclination to bother about such tiny people. Indeed, in the worldwide upheaval, the smaller units of the empire counted for little: they could only look helplessly on at the struggle of the giants.

In the neighbouring island of Sardinia no such reckless coups and counter-coups were attempted; but the chance survival of a first-hand piece of evidence gives us perhaps a better impression of the day-to-day work of a provincial governor even in a year of crisis. In 1866 a bronze inscribed tablet, now in the museum at Sassari, was found by peasants near the village of Esterzili in the south-east central portion of the island east of the upper Flumendosa. Boundary disputes are endemic in Mediterranean civilizations, and on high bare ground such as this there was a standing tendency for the poorer mountaineers to attempt to trespass on richer land below. The inscription runs:

18 March in the consulship of the emperor Otho Caesar Augustus, verified copy of an entry in the portable volume of statutes of L. Helvius Agrippa proconsul exhibited by the quaestorial secretary Cn. Egnatius Fuscus, the said entry being document number 5, heads 8, 9 and 10 as follows:

On 13 March L. Helvius Agrippa proconsul reviewed the case and pronounced sentence:

WHEREAS for the public good it is desirable to abide by judicial decisions once made, and in the matter of the Patulcenses the highly respected imperial procurator M. Juventius Rixa [A.D. 66/67] more than once pronounced that the territory of the Patulcenses should remain unchanged according to the delimitation published by M. Marcellus on a bronze tablet [in 115 B.C.] and on the last occasion pronounced that because the Galillenses frequentiy reopened the issue and disobeyed his decree, he had wished to punish them, but in consideration of the clemency of the emperor best and greatest had been content to admonish them in an edict that they should be still and abide by judicial decisions once made and at latest by 1 October next [A.D. 66] should evacuate the farm-lands belonging to the Patulcenses and should surrender them with vacant possession; and that if they persevered in their disobedience, he would severely punish the ring-leaders of rebellion AND WHEREAS afterwards the highly distinguished senator Caecilius Simplex [proconsul A.D. 67/68] when approached by the Galillenses in connexion with the same dispute with the assurance that they would produce a document referring to the matter from the imperial chancellery pronounced that it was a humane action that postponement should be granted to the petitioners to prove their case and in fact granted them the space of three months up to i December [A.D. 67] on the understanding that unless a constitution had been produced by that date he would follow that which existed in the province

NOW THEREFORE having myself been approached by the Galillenses excusing themselves for the fact that the constitution had not yet arrived and having granted respite until 1 February next [A.D. 69] and understanding that a delay is desired by the farmers in occupation of the lands in dispute I HEREBY ORDAIN AND PRONOUNCE that the Galilenses [sic] shall by 1 April next [A.D. 69] depart from the lands of the Patulcenses Campani upon which they some time ago trespassed. If they do not obey this ordinance and pronouncement, let them know that they will incur punishment for their longstanding disobedience which has already been repeatedly denounced. PRESENT IN COUNCIL

M. Julius Romulus, Vice-Governor; T. Atilius Sabinus, Financial Secretary; M. Stertinius Rufus junior; Sex. Aelius Modestus; P. Lucretius Clemens; M. Domitius Vitalis; M. Justus Fidus; M. Stertinius Rufus IN WITNESS WHEREOF THE FOLLOWING HAVE AFFIXED THEIR SEALS: [eleven names]25

Here are some instructive insights into Roman documentation and above all into the relations between a Roman administration and the provincials: the obstinate occupation of neighbours’ land, the official care to refer to and abide by decisions delivered many years previously, the weakness of the system of annually changing senatorial governors, the ineffective repetition of threats of punishment not clearly specified and not applied. In the eyes of a senatorial Roman governor (and the province had in 67 become senatorial instead of imperial, although an imperial decree (‘constitution’)—if previously or now existing—would be valid) such little squabbles over land were matters of slight importance, and delay was encouraged by the troubles of 68 and 69. It was, of course, inconceivable that Nero, Galba, Otho or their civil service would have either the time or the interest to deal with petty matters in a remote and only partly Romanized country. Similar disputes occurred continually in every corner of the Mediterranean world. We may compare, for instance, the appointment of arbitrators by Pompeius Silvanus, governor of Dalmatia, made in this very year or shortly before—officials whose thankless task it was to sort out longstanding boundary arguments between small communities behind Zadar, in one of the few fruitful areas of the Dalmatian coast. Nevertheless we should perhaps praise the patient and careful legalism of the Romans rather than condemn the ease with which trespassers—if such they were—could cock a snook at the authorities. Incidentally, if it is true, as seems likely, that the Sardinian governor’s legal draughtsmen were not ignorant in March of the consular arrangements made by Otho at least a month earlier, we learn from the inscription that Otho had not, as is generally believed, resigned the consulship at the end of February 69. Like Vitellius, he may have declared himself consul perpetuus.26

While Corsica was murdering its ambitious governor and Sardinia disputing on tribal boundaries, to their north the Ligurian campaign was in full swing—if that is not too grandiose a title for the rather tentative fighting caused by the Othonian amphibious expedition along the coast of Liguria. The nature of this fighting illustrates another aspect of civil war: the impact upon civilians of troops whose discipline and sense of responsibility to a firmly constituted authority have evaporated.

In February, on hearing that Valens and Caecina were on the way, Otho decided that, despite his lack of legionary troops near at hand, some attempt would have to be made to bar the most obvious point of entry into Italy from the north-west. Snow could reasonably be expected to block most of the Alpine passes until April; but the Aurelian Way (Aries-Aix-Fréjus-Antibes-Cimiez-Ventimiglia-Genoa-Pisa-Rome) presented an easy route even in winter. Only a few months before, when Otho had marched along it from Spain, he was reminded, by inscriptions upon milestones, of the extensive work carried out on it by Nero in 58. The highway was in good repair and near sea-level. He would now use what resources he had to dominate the coast road into the Var and possibly enter Gaul. And whatever his shortage of legionaries, he felt he could rely on his Praetorians and the fleet—especially those naval personnel set upon by Galba when he entered Rome and since then enrolled in a legion by himself, even though the formation had not yet been formally constituted and given a name, number and eagle. To these men were added some Urban Cohorts, admittedly of slight military value, and drafts from the Praetorians. The mixed force was to be commanded by two senior centurions, Antonius Novellus and Suedius Clemens, together with Aemilius Pacensis, to whom—perhaps for services rendered in January—Otho had restored the rank of tribune of the Urban Cohort, of which Galba had deprived him. The outset of the expedition was scarcely propitious. When it got under way on about 10 February, the weather being kindly, Aemilius Pacensis was for reasons unknown put under arrest by his own troops, while Antonius Novellus proved to be a nonentity. In this three-cornered rivalry, Titus Suedius Clemens came clearly out on top. Even Tacitus gives him grudging praise for his determination, and he was to continue his career under the Flavians: in 81 he turns up again as camp commandant of the Third (Cyrenaican) and Twenty-Second Legions stationed in Egypt. It was perhaps a good thing that there seemed to be no sign of the appearance of Valens’ army on the coast, and if Clemens’ intelligence was good and he had learned that the Vitellian commander had turned off the Rhone valley into that of the Drôme with the evident intention of using the Mt Genevre Pass, he may well have reported this immediately to Otho, whose plan of campaign it obviously affected. By the beginning of March, having sorted out its command structure, the expedition was approaching the little province of the Maritime Alps, whose chief towns were Cimiez (behind Nice) and Vence, and whose hinterland embraced the valleys of the Var, the Vésubie and the Tinée. The local governor, Marius Maturus, was vigorous and pro-Vitellian, and did his best to keep out the unwelcome intruders. He called up the mountaineers of his province, but this amateur militia (he had nothing else, it seems) was quite unable to face even third-rate Roman troops. In a brush east of Cimiez it was scattered to its remote hillsides, where the Othonians had neither the will nor the knowledge to follow. There was no booty to be had from men who lived by herding sheep in the mountains, their diet mutton, milk and a drink made from barley.27

But this attempt at resistance, however ineffectual, induced an ugly temper and the Othonians turned (somewhat illogically, surely) against the Italian district around Ventimiglia immediately to the east. The disorderly troops proceeded to burn and plunder with a brutality rendered even more frightful by the total lack of precautions everywhere against such an unforeseen emergency. The men were away in the fields, the farmhouses were open and defenceless. As the farmers and their wives and children ran out, they met their end, victims of war in what they thought was peace. Among these victims was Julia Procilla, the mother of Agricola, Tacitus’ father-in-law. A rich lady from Fréjus, she had estates outside Ventimiglia. When the news of the fatal disaster reached Rome, where Agricola was perhaps still continuing the temple inventory assigned him by Galba, he set out north to pay his last respects and settle up the family affairs. His presence in the area of Ventimiglia and Fréjus during the summer months of 69 stimulated the historian’s knowledge of, and interest in, events in that quarter.

The news of this Othonian activity on the coast had been reported to Valens at Gap in early March by messengers sent no doubt by Marius Maturus over the mountains via Digne. In response, Valens detached two auxiliary cohorts, four troops of unidentified cavalry and a whole regiment of Treviran horse under its commander Julius Classicus, a name fated to recur. The total effective can hardly have exceeded 2,600 and may have been less. These troops, with some additional forces of little value, proceeded to Fréjus, where a proportion was left as a rearguard. About 22 March, perhaps between Menton and Ventimiglia, contact was made with the Othonians, who had less cavalry, but more infantry—and above all a fleet. While the land forces were engaged, the fleet sailed past behind the Vitellians and completed a discomfiture begun by a failed cavalry charge. Only dusk, if we are to believe Tacitus, saved the small Vitellian force from annihilation. A few days later, they were reinforced from Fréjus and suddenly attacked the Othonian camp, with initial success; but their opponents rallied and once more inflicted and also suffered some losses. In this last encounter there was no clear victory for either side and by tacit consent a truce was called, the Vitellians going back as far as Antibes and the Othonians as far as Albenga. Eighty miles now separated the opponents. The long withdrawal by the Vitellians is understandable: they desired proximity to their reserves at Fréjus and a gap between themselves and the victors; as for the Othonians, who had proved superior, the move may be explained by a desire to keep an eye on the passes through the Apennines from the plain of Piedmont where Valens had now arrived. An appeal to him by the Vitellian coastal force at the end of March was, after some hesitations, rejected.

The Ligurian campaign has been dismissed by historians as a pointless and ill-conducted foray, or elevated into a totally incredible attempt at a grandiose Othonian pincers movement. The truth lies somewhere between these views. Though Otho may have been a knave, he was not a fool. The wish to close an obviously open door in the face of an invader believed likely to enter by it is not folly; nor was it folly on the part of Suedius Clemens to move back to Albenga. Thus, though Otho’s expedition failed to secure a footing in Southern Gaul or to detach substantial portions of the southern Vitellian army, it did, along with other factors, direct Valens’ thrust towards Pavia and Cremona, and destroy any thought of turning the Othonian position on the Po by the use of the coast road to Rome. It was in the plains of northern Italy that the campaign would be won and lost.

In the first week of March Caecina Alienus led the Twenty-First Legion and his other heavy troops through Aosta down the valley of the Dora Baltea to Ivrea and the other cities of the Eleventh Region, already occupied by his light forces. He encountered no resistance, and discipline was good: it was vital to make a favourable impression upon Italy. However, when Caecina had occasion to address reception committees properly dressed in togas, eyebrows were raised when he appeared in the military dress (breeches, a practical garment in the north now being adopted by the army, and a general’s bright cloak) normally laid aside in a civilian context. His wife, too, made tongues wag: instead of preserving a decent decorum, she paraded in public on horseback in a loud purple dress. Women had no business to flaunt themselves in this brazen manner.

Before Caecina reached the Po, his auxiliaries had already approached it at various points on its upper course. They found that it was defended by light Othonian forces of no great military value. They had mopped up a few troops of cavalry and 1,000 sailors of the Ravenna fleet between Pavia and Piacenza. Opposite the latter city, the amphibious Batavian and German cavalry used their special skills to cross the River Po and make prisoners of a few Othonian reconnaissance parties sent out from the city, whose centre lay more than a kilometre south of the bank; while north of the river and downstream, the invaders actually captured a cohort of Pannonians near Cremona, and may already at this early date have occupied the town. By this advance they had crossed the River Adda, moving from the Eleventh to the Tenth Region, which was otherwise in Othonian hands. Cremona now, or a little later, gave the Vitellians a warm welcome, and continued to do so for much of the year.

By 20 March Caecina and his legionaries were on the Po. Elated by the easy successes of his auxiliaries, the general now tried a head-on attack upon Piacenza. For some ten days this key town had been held by a spirited Othonian commander, Titus Vestricius Spurinna, now in his forties, known many years later to the Younger Pliny as a lively old man with a fund of anecdotes relating to his long and distinguished career and his many acquaintances. The commander’s enterprise and discretion supplied the deficiencies of his troops. These were only some 2,700 in number, of which 1,500 were provided by three Praetorian cohorts more accustomed to ceremonial duties in Rome than to marching, digging and fighting. In addition he had 1,000 men drawn from the various infantry vexillations in Rome and a few cavalry. Prudence dictated strengthening the defences of Piacenza, but the men were truculent and suspicious of the command, scented treachery to Otho, and after hearing on their arrival of the behaviour of the Silian cavalry regiment and the reverses near Pavia and at Cremona, demanded some sort of offensive. Unable to control these would-be heroes, Spurinna determined to teach them a lesson. If they desired to venture out against the enemy, well and good: he would be their leader. About 11 March, he quietly moved the Praetorians out on a long route-march westwards, but on the south side of the river, using the Via Postumia and ostensibly making towards Pavia. There was, he knew, little real risk in this, for Caecina’s legionaries were still some 120 miles away in the neighbourhood of Novara, and Valens had not even reached the Alps. Towards evening, he turned off the Via Postumia down a side road leading to a minor crossing point, and ordered his men to encamp for the night at Pievetta. The long day’s march of seventeen miles was followed by digging rendered more onerous by the smallness of the force. Blistered feet and hands, weariness and muscle-ache worked marvels. The hotheads began to take a different view of the grandeur of war. The next morning, the older and less excitable men pointed out to their subdued comrades the danger involved in the exposure in open country of 1,500 Praetorians to many times that number of hardened legionaries. The centurions and tribunes made use of the changed attitude, and the troops had to agree that there was much to be said for Spurinna’s policy of resisting the enemy behind the walls of the well-stocked city of Piacenza. Finally Spurinna explained his proposals without indulging in recriminations, and the whole force trooped back to the fortress, a small reconnaissance party being left at the river crossing. A week was available for reinforcing the city walls, neglected, like those of the Helvetians’ forts, in a century of peace, for heightening the parapets and for providing arms and some training in the technique of defence. By the time Caecina did arrive, the Othonian force at Piacenza was in better heart and improved form; but Spurinna immediately reported the arrival of the enemy, and their apparent strength, to his colleague Annius Gallus. Gallus had left Rome together with Spurinna but had turned off the Aemilian Way. No authority gives us a clear account of Gallus’ movement at this time, but probability suggests that he first of all occupied the crossing points of the Po below Cremona, those at Brescello and Ostiglia—the bridges here would have to be guarded, and their possession enabled Gallus to face westwards on both banks of the Po. At the moment of receiving Spurinna’s warning he seems to have been operating in the area of Verona with the slightly optimistic idea of welcoming the inflowing Danube troops. He now decided that his presence at Piacenza was vital, and set off south-westwards.28*

At Piacenza, the two-day encounter began with a few verbal exchanges that led to nothing. Then the Vitellian commander launched a vigorous but careless assault. The men approached the walls with bibulous bravado, after the main meal of the day, well washed down. Their use of slingshots and inflammatory missiles proved a failure, the only effective result being the destruction of the amphitheatre outside the walls, the biggest in Italy, and apparently now used as a strong-point in the defensive scheme. Afterwards, gossip attributed the loss, quite unrealistically, to a few jealous Cremonese camp followers in Caecina’s army: Cremona had no such splendid building.

Soon after first light on the following day a much more determined attack was mounted. Admittedly not much could be achieved by the wild assaults of the German auxiliaries who with bared bodies and native battle songs clashed their shields over their heads in a preliminary war dance. Such primitive warriors could not stand up to the rain of javelins and stones from the walls. The Vitellian legionaries understood their business better. Heavy fire was directed at the ramparts to keep the defenders as far as possible behind the merlons and provide cover for the attack below, where the standard techniques of tortoise, mound and mantlet were employed to pierce the wall; and men wielding crowbars attacked the gates. At suitable points the Othonians hurled down millstones collected for the purpose, and many of the attackers beneath were crushed to death. Finally, after a hard struggle, the attack had to be called off, and Caecina retired in discomfiture across the Po to his base at Cremona, less than two days’ march (30 Roman miles) distant.

The failure at Piacenza was a regrettable check for Caecina, but perhaps hardly the disaster that the admirers of Spurinna may have represented it to be. Clearly, at some time or other the defences along the Po had to be probed, and if Piacenza proved too strong there were plenty of other crossings. As the Vitellians marched away, they were joined by naval personnel detached from the Ravenna fleet under a centurion who knew Caecina and by Julius Briganticus, the commander of a cavalry regiment, nephew—and enemy—of the Batavian leader Civilis, and now a lone wolf far from his territory with only a few followers.

As for Spurinna, on discovering that the enemy had stolen away to the north-east he wrote to his colleague Annius Gallus countermanding any reinforcement of Piacenza. The danger point was now Cremona. On receiving the news, Gallus halted his force, consisting of the First (Support) Legion, two Praetorian cohorts and a cavalry element (totalling perhaps 6,500), at a small village on the Postumian Way called Bedriacum. It lay north of the Po and roughly midway between Cremona and Mantua, commanding a road junction. The name of this tiny spot, as insignificant as its modern successor Tornata, was to be famous—and ill-omened—in Roman history.