The First Battle of Cremona

The task confronting the Othonian commanders was no easy one. To construct a camp in close proximity to a hostile force was a difficult operation, though it was not infrequently done in battle with undisciplined barbarians, and Roman troops were trained in the necessary drill. But as the cumbrous army moved off, an observer might have been forgiven for supposing that it was setting out for a distant campaign, not for an imminent engagement. On the narrow road was a large part of the Othonian army, laden with all the equipment, including timber ready cut, necessary for constructing the advanced camp, to be sited some four miles only from that of the enemy, close to Caecina’s bridge over the Po, which was also defended. The distance involved, twenty miles, was decidedly in excess of what could be covered in one day if massive digging operations were necessary on arrival. A start was therefore made on 13 April, and in order to achieve such secrecy as was attainable in a manoeuvre extending over two days, it was decided that on the first of these they should not venture within the probable range of enemy reconnaissance, about a dozen miles.33

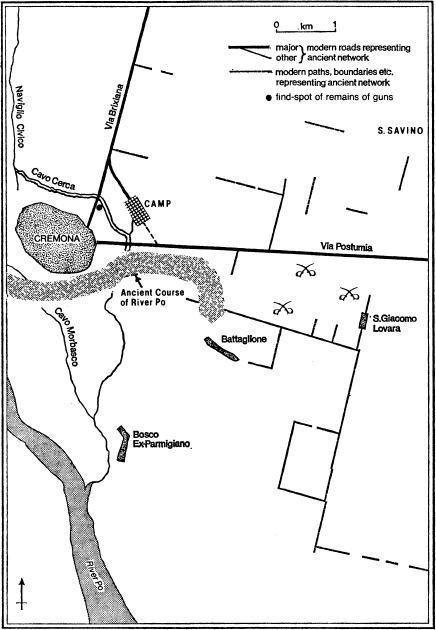

On the afternoon of 13 April the army moved out of camp westward, and having covered four miles only encamped between the modern villages of Voltido and Recorfano, at the apex of the triangle whose long sides are formed by the Via Postumia and the grid track through Recorfano, and upon whose hypotenuse lies the village of Tornata.* The command selected a site which, as peevish critics remarked, managed to be without water in a countryside full of streams in spring spate. The complaint is trivial, for water cannot have been far away, but it well illustrates the childish recriminations with which military men sometimes stud their memoirs. The important aim, secrecy, was achieved, for it was not on the evening of 13 April but only on the morning of the following day that the Vitellian scouts reported the advance of the Othonians, now very much nearer Cremona. For the same reason the first day’s camp, like that which they had just left, lay slightly off the line of the highroad. Brief as the distance from Bedriacum was, it was worth covering on the 13th; it enabled the next day’s march to fall slightly short of the normal infantry prescription.* Given an early start, they could march sixteen miles in five hours and still have plenty of time for digging. Roman practice suggests that the camp construction would have been done by one legion while the rest stood on guard, and several hours’ work with the spade would be necessary in view of the size of the army.

Fig.3 The site of the First Battle of cremona

That evening Titianus and the generals debated the following day’s route. They had to decide whether, and how far, to follow the main road on 14 April. The use of the centuriation limites, paths or tracks parallel and at right angles to the highroad, would eventually bring them to the desired position. But these dirt tracks and baulk paths were muddy in spring, and would inevitably slow the advance of the baggage vehicles and therefore of the whole army to two miles an hour or less. This was intolerable. Most of the day would be consumed by such a slow and painful advance. On the other hand, the use of the metalled Via Postumia, while speeding up the rate of march, would also increase the risk of detection, for wherever else the Vitellian scouts might or might not be, they must certainly be expected to patrol the main thoroughfare. Tacitus, however, seems to conceive of the debate as hinging on the desirability or otherwise of waiting until Otho appeared with his Praetorian escort. This is quite certainly a serious misconception. It had already been decided by Otho on 12 April, with the consent of Suetonius and Celsus and therefore a fortiori with that of the obsequious Titianus and Proculus, that the emperor would hold Brescello: that issue at least cannot have arisen at this point, though it no doubt did in many a post-mortem afterwards. And the historian uses language * which could be understood (and usually is understood) to mean: ‘They hesitated whether to fight’—as if that decision, too, had not been thoroughly thrashed out and settled at the council of war at Bedriacum. But the words are also capable of bearing a different, and preferable, sense: ‘Debate arose on the chances of a battle developing during the march.’ This is intelligible. The difficulty was to know how best to compromise between the two alternatives. How soon or how late should the advantage of speed on the highway be exchanged for greater security on the by-way? Should they take the turn to S. Giacomo Lovara, less than four miles from the Cremona camp, but leading by the shortest route to the bridge area? Or should they travel south of the Via Postumia by safe, slow tracks? Suetonius Paulinus characteristically voted for the latter, even though it would involve a late arrival.

But the historian cannot always read the secret thoughts of men. We cannot exclude the possibility that caution and patriotism may, at the back of Suetonius’ mind, have toyed with the possibility of a compromise between the generals on both sides before the fatal battle started. For this, time was necessary. There are a number of hints in our sources that there was a widespread fear on the Othonian side of ‘treachery’—a fear not diminished by the calculation that such a solution would avoid the shame and loss involved in warfare between Roman and Roman.

The debate on the evening of 13 April was indecisive. It was continued on the next morning and had not reached a conclusion when a Numidian horseman brought an urgent message from Otho, pressing for speed at all costs. But what event had occurred since 12 April to render this curious hastener necessary? There are two possibilities. Titianus and Proculus, neither of them experienced in active warfare, may have felt unable to come to a decision without consulting Otho; and if so, the exchange of messages could have been made between Voltido and Brescello during the night of 13/14 April. Alternatively, Otho himself may have received news which increased his anxiety. Had Flavius Sabinus discovered the absence of his two Praetorian tribunes on the errand described below, and had he believed that his whole force, to whom he had just come as a stranger, was unreliable? Whatever the cause of Otho’s desire for haste—and the phenomenon was debated at length by contemporaries—it tilted the balance of decision. Titianus and Proculus, outvoted though they were by Suetonius, Celsus and others, used their rank to overrule all further opposition: the army would keep to the Via Postumia and take the more dangerous S. Giacomo turn. The van was to consist of two auxiliary cavalry regiments, whose task it would be to ward off an attack or create a diversion beyond the road junction which constituted the danger point of closest approach to the enemy. Then the sequence was to be the First (Support) Legion, the Praetorians, the Thirteenth Legion and the 2,000-strong advance party of the Fourteenth Legion, the baggage being interspersed between the formations. The whole column would be supplemented by auxiliaries.

A little later on the same morning, Caecina was supervising the construction, or rather the reconstruction, of the bridge near the confluence of the Cavo Cerca and the Po, when the commanders of two Othonian Praetorian cohorts came up to him. They asked for an interview. As things turned out, the interview never took place, and on these men and their proposals the historical tradition seems to have derived no information from the memoirs or recollections of Caecina, who had no reason to speculate on the hypothetical proposals of a defeated enemy. Consequently, Tacitus, too, is silent on their identity and intention. Their démarche invites surmise. The disposition of the Praetorian cohorts is known. Of the three originally assigned to Spurinna in March, one had been taken away from him by the time of the Castors engagement: at this, three—clearly Gallus’ two and Spurinna’s one—were present. The remainder—apart from the drafts given to Suedius Clemens—accompanied Otho from Rome and were now mostly with him at Brescello, while one or two may have been left with the Bedriacum army. The obvious answer to our question on the identity of the two cohort commanders is that the units concerned are those which Spurinna was ordered to bring eastwards to reinforce the gladiators south of Cremona, a movement which must have taken place on 13 April. Otho’s transfer of the command at this point from Macer to Flavius Sabinus is described as welcome to the gladiators; but we have no information concerning the reaction of the two Praetorian cohorts when they found that Spurinna had been ordered to move them from the city which they had defended so successfully and brigade them with gladiators under a new general. They—or their officers—may have decided that Otho’s cause, now guided or misguided by Titianus and Proculus, stood little chance against the combination of Caecina’s and Valens’ armies if conclusions were to be tried immediately. So far speculation. What is certain, and consistent with the theory, is that the attack launched on 14 April by the gladiators (there is no mention precisely of the Praetorians) was a failure, and that after the battle violent language was used about the treason of certain elements.* Since this charge cannot be levelled against the main body of the Othonians at the First Battle of Cremona, it may relate to the only other Praetorian force in the offing: the two cohorts on the south bank. The intention of the interview sought with Caecina by the commanders was almost certainly to explore the possibility of avoiding a head-on collision of the legions by some sort of political compromise, almost certainly a protest against the futility of civil war. Whether this attempt should be described, to use Tacitus’ terms, as ‘treachery’ or as ‘some honourable plan’ designed to avoid pointless bloodshed is an academic, if not a philosophical, question. In the event, the interview fell through, and the battle was fought.

Scarcely had the tribunes begun to speak to Caecina than their words were cut short by the arrival of scouts who told the Vitellian general that the enemy army was at hand. Dismissing the officers, Caecina mounted his horse and made at full gallop the ten- or fifteen-minute ride to the main camp three miles away. Here he found that the legions had already been alerted, and arms issued to them. They were now drawing lots to determine the order of march and of array. The First Battle of Cremona was about to begin.

All warfare and all battles are to a degree enveloped in chaos and confusion. The somewhat conflicting and unsatisfactory evidence for the course of the First Battle of Cremona (as it should be called) attests the piecemeal impressions left upon observers by the various aspects of a loosely and untidily fought engagement. Both the nature of the terrain and the character of the Othonian marching column divided the battle into a series of almost independent encounters. What is quite clear is that the Vitellians were more firmly led and enjoyed better intelligence, a higher degree of preparedness and coordination, and above all superior numbers. No one who studies the circumstances can be in the least surprised by the upshot.

While the legions of Caecina and Valens were drawing lots, the Vitellian cavalry galloped out of the camp eastwards towards the enemy. Despite numerical superiority, they were repulsed by the Othonian vanguard, consisting of two cavalry regiments, one from Pannonia and one from Moesia, the latter a very early arrival from that area. In the interval since the Vitellian scouts warned Caecina (and no doubt Valens, too, at approximately the same time) of the Othonian advance, the forces of Titianus and Proculus had approached the turn to S. Giacomo Lovara. While the infantry and interspersed baggage began to turn left towards the Po and the bridge, the two cavalry units had continued onward along the Via Postumia with the intention of engaging, or at any rate distracting, the Vitellians, who, if one considered the obstacles to sight presented by the dense vineyards on the east of the town, might be expected not to know precisely what was afoot. It is evident that this supposition was unduly optimistic. But the Othonian cavalry did their work well, and it is perhaps not too venturesome to see here the competence that Marius Celsus had already demonstrated at the Castors. So effective were they that the Vitellian auxiliary cavalry would have been pushed right back to the walls of the camp, had not their vanguard legion, the First (Italian), emerged to stem the rout. Drawing their swords, they compelled the retreating horsemen to face about and resume the fight.

By this time the leading Othonian legion, the First (Support), had moved on to the branch road and made its way about a mile from the junction, emerging into more open country as it drew nearer to the Po. But behind it, and along the Via Postumia in the direction of Bedriacum, there was considerable disorder and confusion. The formations were divided and slowed up by the baggage trains, and there seems to have been little cavalry to provide a screen. Visibility was poor. The solid supports upon which the vines were trained and trellised impeded both the visual tactical signals upon which a Roman army heavily depended, and the movements themselves which those signals were designed to control. While the Praetorians in the middle of the marching column seem to have remained on and around the main road, the Thirteenth and the vexillation of the Fourteenth had to deploy to the right to form some kind of line no doubt parallel with the north-south lines of the centuriation grid at that point. Some men were able to see and rally round their legionary and manipular standards, others were looking for them. There was a confused hubbub of rushing and shouting troops—an evil augury in any force representative of an army which prided itself upon its discipline, its clear chain of command and its coherence in battle. An unfortunate rumour added to the disarray. For some reason or other—treachery was afterwards alleged, or else a rumour intentionally spread by Vitellian agents—the men of I (Support) got it into their heads that their Vitellian opponents had decided to desert to their side. The cheers and greetings of the Othonians were answered by fierce yells and abuse. This incident was doubly unfortunate for the Othonians. It convinced the Vitellians that they had no fight in them, and I (Support) sapped the morale of its fellow formations by creating the suspicion that it meant to desert. A further difficulty was the presence in and around the Via Postumia of minor watercourses, obstacles sufficient to slow up infantry. Even the highroad presented a problem by its relative narrowness. It was not raised on an embankment above the surrounding countryside as Tacitus, perhaps misled by the word agger in his sources, seems to imply and as some modern historians confidently assert; but the term is justified by the presence of drainage ditches on either side, which still survive in an attenuated—or sometimes an amplified—form, spanned occasionally by culverts giving access to the fields. But the main impediment to the orderly deployment was probably the watercourses whose modern descendants bear the names of the Roggia Gambara and the Dugale Dossolo, flowing south, and the Roggia Emilia and Dugale Gambalone, flowing east. This was not the kind of land envisaged in the training manuals of the Roman army.

As one approached the Po, the landscape opened up. Neither ditches nor vineyards troubled the inexperienced but spirited First (Support) as it faced the Vitellian Twenty-First (Hurricane) Legion. The latter, like its fellows, had marched out from the camp in good order, knowing where to go and what to do. The Othonian formation, raised by Nero from naval personnel and formally embodied by Galba, probably in the preceding December, had never fought a legionary battle before. But it was well-led, in high spirits and eager to win its spurs. In an initial dash—after recovering from the effects of the misunderstanding—it overran the front ranks of its opponents and carried off their eagle. This was the ultimate disgrace for a Roman legion. Smarting under it, the Vitellians charged the attackers in return, killing the commander Orfidius Benignus and capturing not indeed the eagle, but a number of standards and flags. The effect on the First (Support) Legion of this severe counter-attack, and especially of the loss of its commander, seems to have been that it fell back and left the troops on its right in an exposed position.

At the other end of the Othonian line, at or north of S. Savino, the Thirteenth and the advance party of the Fourteenth, apparently unprotected by auxiliary and cavalry forces and infantry, faced the Vitellian Fifth Legion. While some details are not clear here, the 2,000-strong vexillation apparently found itself enveloped. It was rolled up from the north, while the Thirteenth under Vedius Aquila (who seems to have lost his head) could not hold the attack of the Fifth, led by the popular Fabius Fabullus. It was here that the unpreparedness of the Othonians for battle was most marked, and here that the obstacles of vine and ditch were most prominent. Lateral contact seems to have been lost, in Roman eyes a cardinal error. The Othonian right wing began to yield ground as the left had done.

PLATE 3 An inscription commemorating piso and his widow verania

PLATE 4 The text of a decree by Lucius Helvius Agrippa, Governor of sardinia

PLATE 5 Otho as Pharaoh of Egypt

The heaviest fighting was in the centre where along and alongside the Via Postumia the Othonian Praetorian cohorts, who cannot have been more than five in number with a strength of 2,500 men, faced the First (Italian) Legion. The latter had already shown its determination by quelling the panic of the Vitellian cavalry. It faced equally determined adversaries in the Othonian Praetorians, than whom nobody had more to lose by defeat. Here, as it turned out, the issue of the whole campaign was decided. The two sides fought hand to hand, throwing against each other the weight of their bodies and bossed shields. The usual discharge of javelins had been discarded, and swords and axes were used to pierce helmets and armour. It was a measure of the desperate folly of this war that these opponents often knew each other personally. Whereas the navy men of the First (Support) Legion had never seen troops long stationed in Windisch, and whereas the Thirteenth (in Pannonia from A.D. 46) and the draft of the itinerant Fourteenth (in Britain from 43 to 67) had nothing in common with the Fifth, in which, cross-postings excepted, there served no single individual who could remember any other station than Vetera in Lower Germany, the contestants in the centre had probably trained side by side. The Othonian Praetorians—substantially the Praetorians of Galba and Nero—must surely have met or worked alongside the men of the First (Italian) when both formations were training for Nero’s campaign in the East in 67, perhaps already in 66. Many will have recognized a comrade in the enemy ranks.* A battle between such evenly matched enemies was inevitably bitter and for long undecided; high praise must be given to those numerically and in other ways at a disadvantage—the Othonians. But when the left and right wings of their army yielded, even the devotion of the Praetorians to their emperor availed no more.

The final blow to any chance of an Othonian recovery was one which no one on their side could have anticipated. On the afternoon of 14 April, in accordance with Otho’s instructions, Flavius Sabinus had placed his gladiators in the Ravenna galleys and got them across the Po to deliver the diversionary attack on the Vitellians from the south. This, together with the advance of the cavalry from Pannonia and Moesia, was designed to prevent the Vitellians from interfering with the Othonian advance and the proposed construction of the forward camp. In our sources there is no mention of the two Praetorian cohorts brought up from Piacenza on the previous day. We may guess the reason. It was an incident which Spurinna, whatever his penchant for dinner-table reminiscences in after days, can scarcely have been pleased to remember, still less to relate. Flavius Sabinus had noticed early in the day that the commanders of the two cohorts had disappeared. Officers do not disappear unless they mean treachery, especially on the eve of a battle. Sabinus had concluded that, if the tribunes were traitors, it would be best to keep the troops they commanded out of the way. They took no part in the foray or the battle, and it is their absence or their treason whose condemnation is obscurely voiced in our sources. Without Praetorian support, the small band of gladiators succeeded in crossing the river. In view of the near certainty that the Vitellians were well-informed of the situation, they were probably allowed to do so. When they had proceeded some way from the bank, they were suddenly attacked by the Batavians under Alfenus Varus. Most of them fled back to the Po, where they were cut to pieces by other Batavian cohorts stationed there to block the retreat. The victors, having disposed of the would-be diversionary attack, marched rapidly north-eastwards to join in the main battle. Since the First (Support) Legion had retired, they made contact with the reeling Praetorians and made doubly certain their collapse.*

The battle was now decisively won by the Vitellians. The surviving Othonians, left, right and centre, streamed back to the distant camp fourteen miles away. On the retreat, too, losses were heavy. The roads—the Via Postumia and the limites parallel to it—were choked with dead. Few prisoners were taken. The two Roman armies had fought well in an evil cause, and the Othonians had no reason to feel ashamed of their performance. Their ranks had been broken, but not their spirit. It was some consolation to them to reflect that a large part of their forces had not been committed, and that more were arriving from the Danube. Those who had fought at the First Battle of Cremona had been heavily outnumbered, the victims, they felt, of incompetent leadership and treachery. There was no reason why the tables should not be turned.

Once the Othonian front had collapsed, Caecina and Valens marshalled their forces and moved cautiously forward towards Bedriacum. But dusk was now near. Although they had no tools to dig a proper textbook camp, having come straight from battle, lightly laden, an attack with tired troops upon the strongly-held enemy camp was quite out of the question. Besides, there was a hope that a night’s delay and reflection might induce an Othonian capitulation. Of the morale of the defenders of Bedriacum little was known, and the nearness of their Danubian reinforcements constituted yet another hazard. Every consideration prompted the Vitellians to keep a respectful distance between themselves and Bedriacum. In fact, they bivouacked under arms at a point five miles short of the enemy camp, a little to the west of Voltido.

Meanwhile, what of the Othonian leaders ? They knew the facts, and were guided by the hard logic of the event, not by emotion. Indeed, when the tide of battle turned irreversibly against them, Proculus and Paulinus displayed a prudent disregard for honour. They abandoned their retreating troops and fled westwards from the area of Cremona, making their way by devious and different routes towards their new master from the Rhineland. Of their movements, until they turned up to eat humble pie before Vitellius at Lyon less than ten days later, we know nothing. But dates and distances suppose a hasty journey to secure the audience grudgingly and contemptuously granted. The first Othonian commander to regain Bedriacum, Vedius Aquila, was greeted with jeers and catcalls: it seems that the commander of the Thirteenth (Gemina) was incautious enough to return before nightfall and was immediately surrounded by a noisy mob of troublemakers and runaways, eager to find a scapegoat for defeat. Titianus and Celsus were luckier—or more cautious: by dusk, sentries had been posted and some sort of discipline imposed by Annius Gallus, who, still convalescent from his fall, had been moved to Bedriacum since the council of war and left in charge of the camp during the battle. He appealed for unity, and was listened to with respect. Titianus and Celsus entered unseen and unmolested.

Early on the next morning (15 April), Marius Celsus called together the senior officers to decide between resistance and capitulation. With good reason or by a convenient fiction, he claimed the knowledge that Otho would not wish them to prolong a civil war when the initial contact had been so much in his disfavour. Indeed, Otho would never have plotted against Galba had he known that civil dissension would follow. What good had Cato and Scipio done by prolonging futile fighting in Africa after Caesar had won at Pharsalia? And at that time, in 46 B.C., the struggle had been for liberty versus autocracy, not in favour of this or that emperor. Even in defeat men should employ cool reason in preference to desperate courage. Celsus’ arguments were effective. Since Otho, still alive at Brescello, might have been, but was not, consulted, we must assume that Celsus’ version of the emperor’s attitude was believed. Even his brother did not dissent from it.

It was therefore decided to send Celsus himself to the enemy as a plenipotentiary, offering recognition of Vitellius and a reconciliation of the armies. Before he returned, some time elapsed, longer than that required by a ten-mile journey and by the negotiation of such simple terms. Titianus began to have second thoughts, and manned the walls more heavily in the fear that Celsus had been refused a hearing; and perhaps this last flicker of defiance had been stirred by fresh news of the approach of the Fourteenth Legion from the north-east. If Valens and Caecina had proved difficult, the Othonians could still give a good account of themselves. But soon the watchmen saw Caecina as he rode up on horseback, raising his right hand in a conciliatory salute; soon Celsus himself returned unharmed, though a rough reception from the victims of the Castors battle had had to be checked by their centurions and by the intervention of Caecina. Agreement had been reached, and all was well. The gates of the camp swung open, and the two armies fraternized as passionately as they had fought. The bitterness of some individuals had been swamped by a wider tide of relief: the frightful revenant of civil war had departed, it seemed, and the men of the usurper Marcus Otho swore allegiance to the usurper Aulus Vitellius.

At Brescello Otho and his Praetorians awaited the issue of the battle. Otho was ready to exploit victory or take the consequences of defeat. Whichever way things went, he knew what he would do. Late on the evening of 14 April the ill rumours that travel fast had covered the forty miles from Cremona. Then, during the night and the next morning, wounded men straggled in from the battlefield, telling the full extent of the disaster.

The reaction of the Praetorians was not perhaps surprising. As the men who owed most to Otho and had most to lose by his fall, they had an interest in encouraging him to stand fast and fight another day. But self-interest was reinforced by personal devotion. Since January Otho had grown to the stature of his office, inspiring a loyalty and affection hardly paralleled in the Long Year. The parasite and dilettante had become a leader. On the morning of 15 April there was an emotional scene. The troops gathered in a mass to hear him speak, to offer their own appeals. Distant onlookers saluted Otho, the nearer bystanders threw themselves at his feet, some even clutched his hands. Plotius Firmus, the prefect, expressed the general feeling, and urged Otho not to give up. His appeal was reinforced by a message brought by Moesian mounted elements who had arrived at Bedriacum on 13 April just in time to participate in the battle. After the defeat they had ridden hard to Brescello, forseeing the necessity of offsetting the bad news by providing the latest information of the advance from the Danube. They reported that when, on 9 April, they had left Aquileia, the frontier town of Italy on the north-east, the main party of the Seventh (Galbian) Legion from Petronell had just entered the town: it might be expected in Bedriacum in the course of the next five days. The legionary commander, Antonius Primus, was full of enthusiasm. What was more, the Fourteenth with its great fighting reputation was much nearer: it should arrive at any moment. Behind both came the larger forces of Moesia. There could be no question but that the campaign could be carried on with good prospects of success.

None of these arguments had much effect upon Otho’s resolution: he had no intention of being the cause of further Roman bloodshed. Having failed in the first encounter, it was his duty to renounce his position. Thanking the troops in a dignified speech, he blamed Vitellius for the outbreak of the civil war, and said that he wished to be judged by posterity on the example he had set in preventing its prolongation. Peace demanded his death, and upon this he was irrevocably decided.

He then summoned his staff in order of seniority and paid them his farewells: they were to get away quickly and avoid attracting Vitellius’ annoyance by procrastination. When his followers wept, he restrained their emotional displays with calmness and intrepidity. To those departing up- or downstream along the Po he allocated the available units of the Ravenna fleet, and gave to land travellers horses and diplomata. Any potentially incriminating documents were destroyed. Such loose money as was available he distributed carefully and systematically to each according to his rank and needs. The approach of death had turned the gambler into a man of charity and prudence.

Among his suite was his nephew, the son of Otho Titianus, the young lad Salvius Cocceianus, who had accompanied his father and uncle to see what war was like. The boy was frightened by the sinister turn of events, broken-hearted by the reality of defeat and death. Otho took care to comfort him, saying that Vitellius was not after all an ogre: in return for the immunity accorded to his own mother, wife and children in Rome, he would undoubtedly spare Cocceianus and his father. ‘I had intended,’ he went on, ‘to make you my heir, but thought it best to wait until the position was clear. Now it cannot be. But you must face life with head erect. My last word is this: don’t forget that your uncle was an emperor—and don’t remember it too often either.’ Otho’s estimate of Vitellius’ character was shrewd enough. The boy lived to celebrate his uncle’s birthday for many years. But his memory was too good. In the end devotion helped to secure his death at the whim of Domitian.

After this, Otho dismissed everyone from his presence and rested for a while. Then, in privacy, he wrote two farewell messages. One was to his sister, the other to Statilia Messallina, Nero’s talented and beautiful widow, whom he had planned to marry.* While he was so busied, he was distracted by a sudden disturbance. In the streets of Brescello the Praetorians were threatening the departing senators, especially Ver-ginius Rufus, whom they were holding prisoner within the walls of his lodging. If Otho had renounced the principate, better Verginius than Vitellius! Such hopes were vain. Verginius was even more reluctant in 69 than he had been in 68. Otho reprimanded the ringleaders of the riot in no uncertain terms, secured an end to the disturbances, and personally bade farewell to each of the grandees as they left, making sure that none was molested. Apart from the Praetorian cohorts there was soon no one left except a personal confidential freedman and some servants. From Bedriacum there was no word. One blow at least Otho was spared.

Towards evening he quenched his thirst with a draught of cold water, called for two daggers, carefully tested the blade of each, and placed the sharper one beneath his pillow. Then he went to bed, passing a quiet night and by all accounts enjoying some sleep. At daybreak on 16 April he called his freedman, satisfied himself once more that none of his entourage was left, and told the man: ‘Go and show yourself to the Praetorians, unless you wish to die at their hands: otherwise they will suspect you of having assisted me to die.’ When the man had gone, Otho held the dagger upright with both hands, and fell upon it with the full weight of his body. One groan, and all was over. As the servants accompanied by the Praetorian prefect forced their way in, they found, half concealed and half revealed by his hands, one single wound, in the heart.

The funeral took place immediately. This was what Otho himself had requested, fearing the treatment meted out to Galba three months before. Those Praetorians who were chosen to bear him to the pyre were proud to perform this last service. Emotion ran high. As the cortege passed, the troops crowded around, kissed the wound and hand and feet of the dead man. Those further off knelt. Some indeed committed suicide beside the pyre, not because they were beholden to him for any favour except the privilege of Praetorian service, nor from any fear of the vengeance of Vitellius, but because they were devoted to Otho and wished to share his moment of glory. Afterwards, at Bedriacum, Piacenza, at the camp of the Seventh (Galbian) Legion and that opposite Cremona, there were some officers and men who performed the same frightening act of self-immolation. It is hard to think of any Roman leader who had received such tributes of adoration and despair.

The Praetorian prefect Plotius Firmus acted sensibly. He assembled the troops as soon as possible after the funeral and administered the oath of allegiance to Vitellius. Some of the men refused, and tried to storm Verginius’ billet, but the latter slipped away by a back door and foiled the untimely and unwelcome compulsion. The oath was then sworn by all, and the tribune Rubrius Gallus conveyed to Caecina their adherence, which was accepted. Hostilities now ceased everywhere, and the scattered Othonian formations were told to stand fast pending orders from Vitellius.

The situation was less straightforward for the members of the Senate who had been compelled to follow Otho northwards. They were in a serious predicament. Left behind at Modena, they will have received the news of the defeat at Cremona by the afternoon or evening of 15 April. The troops escorting them—in theory a guard of honour, in fact gaolers—refused to credit the report. Distrusting the fidelity of the senators to Otho, they spied on their every movement and word. Proper deliberation became impossible. Whether Otho intended to fight on, whether indeed he was still alive, was not known. To delay recognition of Vitellius was imprudent: it might be fatal to accord it. Between their fears of future disfavour or immediate death, only evasive and temporizing attitudes could be adopted. Divided in space from their fellow-senators, internally riven by dissension and jealousy, hamstrung by fear of the Praetorians, they could do nothing. Ambitious little men sought to make capital out of the indecision of the prominent, who had to walk with extreme care; and unfortunately the local town council, forgetting the rump in Rome, had put them in an even falser position by addressing them as ‘Conscript Fathers’, as if they possessed or had themselves claimed a constitutional status. The least objectionable decision would be to retire a little towards Rome, an action which could perhaps be explained away whatever happened. The move of twenty-five miles to Bologna providentially occupied most of 16 April.* Perhaps the situation would become clearer. At their new headquarters, desperate for reliable news, they went to the length of posting pickets on the Aemilian Way, the road from Ostiglia and all the minor tracks leading in from the north-west. Thus they managed to intercept the freedman of Otho carrying his farewell messages to his sister and Messallina, written on the previous evening. But all he could tell them was that when he left Brescello the emperor was still alive, concerned only to serve those who would outlive him; for Otho himself life held no more attractions. The mention of the firmness of the defeated emperor was a tacit reproach. The hearers were ashamed to probe further. But they could now assume that Otho was by this time dead, and in their own minds they made their peace with Vitellius. His brother Lucius was present when they met to deliberate anew. Tacitus remarks cynically, and perhaps truly, that he was already courting the attention of the flatterers. Suddenly a new arrival threw the Senate into fresh consternation. Coenus, another of Otho’s freedmen, had turned up. Leaving Brescello later than his colleague and bound equally for Rome, he found that, by the time he had reached Bologna, rumours of Otho’s death had overtaken him. These rumours automatically invalidated warrants signed by an emperor who was, it seemed, no longer alive. The agents of the imperial post at the mansiones were naturally unwilling to supply horses to an Othonian and so court the displeasure of their new master. A bold lie helped Coenus for the moment. The Fourteenth Legion, he asserted, had arrived at Bedriacum on 15 April, joined forces with the garrison there, and defeated the Vitellians bivouacked in the open five miles away to the west. The fabrication was plausible enough. A man well-informed of the military situation might be excused for falling a victim to the deception. At any rate, Coenus achieved his aim, and got away to Rome with his refreshed diplomata. It was true that retribution was shortly to overtake him when the truth was known in the capital, for the authorities there could not afford to be seen to have connived at an act so dangerous to the new régime.

Meanwhile this new development made things even more impossible for the senators at Bologna. Their departure from Modena might after all be interpreted as disloyalty to Otho—if Otho still lived. It would be best to hold no more meetings. It was only on 17 April that the miserable men were put out of their agony. A dispatch from Valens gave details of the Battle of Cremona and confirmed Otho’s death. The forlorn politicians made their own ways back to Rome, keen now to be present at the first official expression of new-found loyalty.

Before the pickets were posted on the roads leading into Bologna, dispatch riders carrying official news of Otho’s death—certified presumably by Plotius Firmus and Otho’s secretary Secundus—had already passed through, not bothering about the Othonian senators who at that moment were installing themselves in the town. Their instructions were to travel at maximum speed to the capital, for it was vital that the rump of the Senate in Rome should be prevented from taking in ignorance any action tending to demonstrate loyalty to an emperor now dead and a cause now lost. A desperately hard ride took them the 344 miles to Rome in less than three days. On 18 April, the penultimate day of the Festival of Ceres, the Senate was hurriedly convoked to hear the fatal and auspicious news. The city prefect, Flavius Sabinus, forthwith administered the oath to the garrison of Rome, substantially now the cohorts of the City and the Watch. The news was brought to the theatre, where there were performances from the 12th to the 18th, and there the audience applauded when the new emperor was named. There was indeed little else that they could do—except for one spontaneous gesture. Adorned with laurel leaves and flowers, they made the round of the temples of Rome, carrying in procession busts of Galba hurriedly removed on 15 January, and, as it seems, since then piously preserved. As a climax to the procession the garlands were heaped in a great mound around the Basin of Curtius, the place stained with the blood of the emperor who had died before their eyes and whom they had been powerless to save. Only by such symbolic acts could the common people of Rome protest against military powers over whom they could exercise no control.

The Senate, however, had to look to the future. It met on the following day to recognize Vitellius. Policy prompted messages of congratulation and thanks to him and the armies of Germany, conveying intimations of the grant to Aulus Vitellius of all the imperial prerogatives—the post of commander-in-chief, the annually renewable power of a tribune of the people, the title of Augustus, together with all the other powers and privileges as granted to Augustus, Tiberius and Claudius. Soon a letter from Fabius Valens addressed to the Senate via the consuls gave details of what had happened as seen from the side of the victors. It was framed in moderate and decent terms; but there were some sticklers for protocol who felt that Caecina Alienus had observed the proprieties better by reporting, as convention prescribed, only to his superior officer Aulus Vitellius. It seemed that already it was possible to detect a slight difference between the blunt professional soldier and his more pliable and politically-minded colleague.

Thus ended the three months’ rule of the usurper Marcus Otho, begun by an act of murderous treachery, ended with a deed of patriotic self-sacrifice. The emperor retains a small but permanent niche in the record provided by Roman historians and poets. Nothing, of course, could excuse in their or our eyes the brutality of the January assassinations, though there were those who sought to find mitigating circumstances in an alleged intention to restore the republic. The time was long past for any such ambition. Whether Piso or Otho, enjoying similar support from those who are faithful servants of any régime, would have made the better ruler, it would be interesting—and most idle—to speculate. What Rome needed was a period of prudent and economical government, and collaboration between emperor and Senate; and it may be that Vitellius was much less likely than either of the other two to secure this end. But the view of Mommsen and others that Otho’s decision not to fight on has no merit, since his life was inevitably forfeit to the victor, is contradicted by a close study of the military situation in April 69. Of this redeeming credit Otho ought not to be deprived, and young Martial was echoing the almost unanimous tradition of the historians when, recalling in Domitian’s reign the Long Year of 69, he penned a prim and simple tribute, whose point, discreetly understated, is that while Julius Caesar was an autocrat whose life was ended by the hands of others, and Cato of Utica a life-long champion of the republic who committed suicide in despair, Otho excelled both; an emperor, he died of his own free choice to help others:

When civil war still in the balance lay

And mincing Otho might have won the day,

Bloodshed too costly did he spare his land,

And pierced his heart with an unfaltering hand.

Caesar to Cato yields, while both drew breath:

Greater than both is Otho in his death.*