two

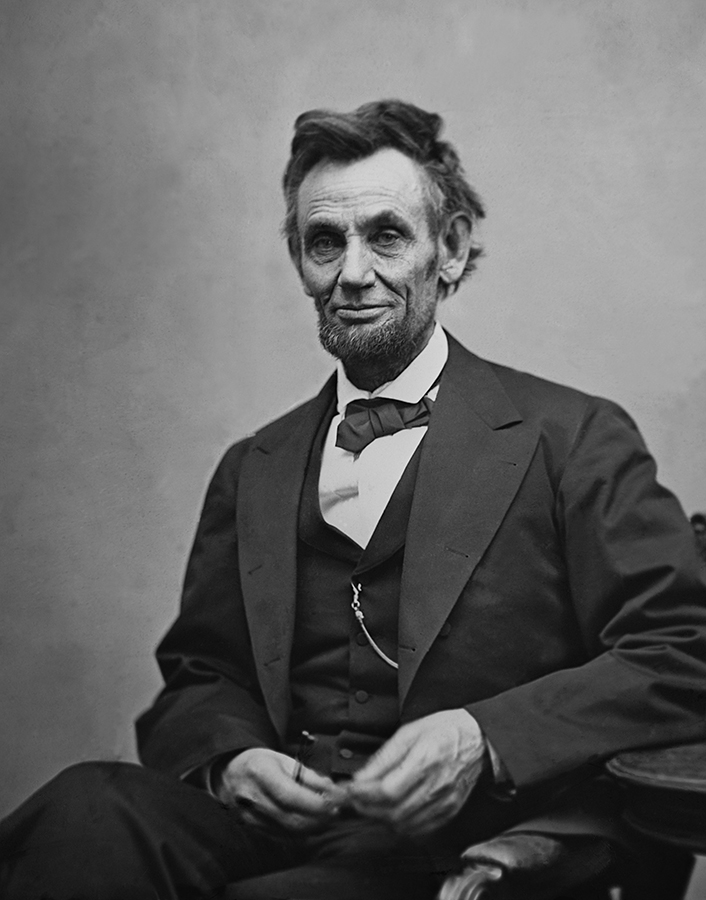

Abraham Lincoln

1809–65

1809 (Feb. 12): Born in Hardin County, Kentucky, to Thomas Lincoln and Nancy Hanks Lincoln.

1816: Lincolns forced to move to Perry County, Indiana.

1818: Nancy Lincoln dies at 34, along with other family members, of “milk sickness.”

1819: Thomas Lincoln marries Sarah Bush Johnston, mother of three.

1828: Sarah, Abraham’s older sister, dies at 21, in childbirth. Lincoln makes first flatboat trip to New Orleans.

1830: Lincolns move again, to Macon County, Illinois.

1831: Abraham leaves home to move to New Salem, Illinois; works as clerk in a store; does some flatboat work.

1832: Buys half-interest in a store with William Berry in New Salem; store would later go bankrupt and Berry would die penniless in 1835, leaving Lincoln saddled with massive debt.

1832 (Mar.): Runs for Illinois General Assembly, at 23, and places eighth out of 13 candidates.

1832 (Apr.–June): Enlists and serves in Black Hawk War; elected captain of his New Salem company.

1833: Appointed local postmaster through help of friends. Works as a self-taught surveyor.

1834: Elected to Illinois General Assembly, as a Whig, to first of four successive terms.

1835: Lincoln’s first love, Ann Rutledge, dies of typhoid fever.

1836: Admitted to Illinois bar, self-taught.

1837: Helps get capital of Illinois moved to Springfield. Lincoln moves there and begins law practice with John T. Stuart. Makes first public statement of opposition to slavery.

1839: Begins stormy courtship with 21-year-old Mary Todd of Kentucky. Travels as a circuit lawyer, gets to know larger territory.

1842: Chooses not to seek reelection to Illinois General Assembly.

1842 (Nov.): Marries Mary Todd.

1843: Son Robert born.

1846: Elected to Congress, as a Whig, from Illinois; serves one term, 1847–49. Son Edward born.

1850: Edward tragically dies at four years old. Son William born.

1851: Thomas Lincoln, Abraham’s father, dies.

1853: Son Thomas “Tad” Lincoln born.

1854: Delivers Peoria speech opposing the Kansas-Nebraska Act. Runs for Senate as a Whig but loses narrowly in Illinois Assembly vote. Becomes nationally known.

1856: Leaves Whigs; joins newly formed Republican Party.

1858: Runs for Senate as a Republican; delivers famous House Divided speech; participates in seven electrifying debates against Stephen A. Douglas; loses the election while gaining national fame.

1860 (Feb.): Gives famous Cooper Union speech in New York City. Touted as presidential candidate.

1860 (May): Nominated as Republican presidential candidate, beating a host of more established political figures.

1860 (Nov.): Elected 16th president of the United States, the first Republican president, defeating three other candidates.

1861 (Mar. 4): Inaugurated president. Seven Southern states had already seceded by Feb. 1.

1861 (Apr. 12): South Carolina fires on Fort Sumter; Civil War begins.

1862 (Feb.): Son William, or “Willie,” dies; Mary unhinged by grief.

1862 (Sept. 24): Suspends habeas corpus nationally to suppress rebellion; 13,000 arrests.

1863 (Jan. 1): Issues Emancipation Proclamation, freeing slaves in rebel states.

1863 (July): Battle of Gettysburg.

1863 (Nov. 19): Delivers Gettysburg Address.

1864 (Nov.): Reelected president after Civil War turns in North’s favor, defeating Democrat and former general George McClellan. Lincoln endorses Thirteenth Amendment abolishing slavery; McClellan opposes.

1865 (Jan.): Thirteenth Amendment passes House.

1865 (Mar.): Delivers second inaugural address.

1865 (Apr. 13): Robert E. Lee surrenders to Ulysses S. Grant at Appomattox.

1865 (Apr. 14): John Wilkes Booth shoots Lincoln in the head on Good Friday, at Ford’s Theatre.

1865 (Apr. 15): Dies at 7:22 a.m.

In 1832, at the youthful age of twenty-three, Abraham Lincoln mounted a campaign for a seat in the Illinois state legislature. In the speech kicking off his campaign, you can already spy his ease with words, his modesty, his humor, and his clear political program: “Fellow Citizens: I presume you know who I am. My name is Abraham Lincoln. My politics is short and sweet, like an old woman’s dance. I am in favor of a national bank, a high and protective tariff, and the internal improvement system. If elected, I will be thankful. If beaten, I can do as I have been doing, work for a living.”1

Noticeably absent? Any reference to slavery—though it was already a potent and inflammatory political issue. The emancipation of the millions of enslaved people and the end of a system of forced labor, rape, and torture were not yet a part of Lincoln’s political thinking. Neither was there any sense of a higher power working through him. For much of his life, Lincoln was a stalwart member of the Whigs, a political party focused on making national infrastructure investments to boost industry. He was not a lifelong antislavery crusader—nor, it could be argued, a lifelong person of faith. His early campaign speeches reflect a man with gifts, but those gifts were deployed to win support for the Whig Party while scraping out a living on the legal circuit. Lincoln was charming, witty, and brilliant, and certainly outworked his peers. But for much of his early life he was what we might dismiss today as a mere partisan loyalist—and not a particularly successful one at that.

We tend to assume that great moral leaders are born moral, become leaders, and are quickly recognized as great. Lincoln, however, is one of those whose cause did not grasp him until later in his life. His peers tended to see an affable and intelligent man, but not a great man. He was well liked and hardworking—but not a moral beacon, not in those early years. He had doubts about just about everything and avoided church.

It was only in the last few years of his life, forged in a crucible of national crisis and civil war, that Abraham became the Lincoln many admire today. His many gifts and skills—through fits and starts, perennial failures, and family tragedies—were brought to bear on the great need of his time. His singular understanding of the role of the Almighty in this world allowed him to find meaning in disaster and drove him to do what was just in spite of the consequences. His tendency toward self-deprecation left him open to the need for a public confession of the sins of an entire nation.

Thirty-three years after that first political speech, Abraham Lincoln addressed the nation as an accidental Republican president turned wartime leader who had won reelection to a second term while supporting a constitutional amendment to ban slavery. Circumstances had left their mark on the man and his words. By the time he rose to deliver his second inaugural address, on a rainy, downcast day, his words were strikingly different from those of the young Whig: “Fondly do we hope—fervently do we pray—that this mighty scourge of war may speedily pass away. Yet, if God wills that it continue, until all the wealth piled by the bond-man’s two hundred and fifty years of unrequited toil shall be sunk, and until every drop of blood drawn with the lash, shall be paid by another drawn with the sword, as was said three thousand years ago, so still it must be said ‘the judgments of the Lord are true and righteous altogether.’”2

HISTORICAL CONTEXT

In 1776, the writers of the American Declaration of Independence sonorously declared: “All men are created equal.” Yet America’s founding reality contradicted that admirable founding dream. Many of the signers of that declaration owned other human beings as property; its primary author, Thomas Jefferson, notoriously raped one of his slaves and fathered children by her. The Constitution of the United States is a brilliant political document, but it entrenched America’s founding sin by declaring that enslaved black Americans counted as only three-fifths of a person on census counts and by denying voting rights to slaves and free women alike.

We wrote earlier that studying great lives can connect us with history, and here is a prime example. We are not the first generation to argue about the legacy of the founders, nor the second, nor the third. The gulf between words and deeds was apparent already when Abraham Lincoln was a young man launching his first political campaign. People were already debating how to reconcile the inspiring dream of what America could be with the nightmarish reality of slavery, conquest, and systems of racial degradation and cruelty. To cling to the dream and refuse to look at the nightmare not only leaves us willfully blind today, but it makes it impossible to learn from countless Americans, such as Abraham Lincoln, who wrestled with exactly that tension in their own time.

The nation Abraham Lincoln was born into in 1809 was built on slavery. Northern banks funded the purchase of slaves, Southern planters relied on slave labor to produce cotton, and coastal merchants shipped that cotton overseas. The young nation’s wealth, as Lincoln himself noted, came from “the bond-man’s two hundred and fifty years of unrequited toil.”3 Race laws were enforced via the “one-drop rule,” which held that any person with even the slightest African ancestry was to be considered black. Slavery was not time-limited indentured servitude but race-based chattel slavery—people bought, sold, bred, held for life, and traded based on the color of their skin.

The defense of slavery, then, was not merely about the prejudice of individual slaveholders or about maintaining their way of life. Racism is the combination of prejudice and power. Racial prejudice authorized and perpetuated slavery, and the institution of slavery made the young nation a moral disaster and an economic power. Even after the end of slavery, that prejudice would combine with and feed off other power structures. Racism continued in the Jim Crow South, in redlining in the North, and in structural barriers to wealth, health, and education today. Simply put, there was a massive amount of money and power tied up in maintaining and expanding the institution of slavery. All of this is crucial to understanding why our nation would tear itself apart in the deadliest war in its history.

In addition to plantation slavery, America had also been a country of small farms, with families scratching out subsistence from the land, and a nation of merchants, tradesmen, and bankers. Nothing like the industrial economy of one century later or the service economy of today existed at the time. But America was changing economically as industry and wage labor grew.

The Democratic-Republicans (later shortened to Democrats, a term we will use throughout) of this time represented the so-called Jeffersonian ideal of a nation of small landed farmers. With President Andrew Jackson as their standard-bearer, they fought for agrarian populism—which, at the time, meant defending the rights of landed white men. They supported slavery and a uniform economy centered in agriculture, and feared centralized economic and political power. In contrast, the Whig Party stood for a strong central government, business, banking and trade, and economic diversity, including a growing industrial sector, and was split internally on slavery. The Whig Party also rode the wave of the Second Great Awakening, a passionate Christian revival movement that filled the nation with evangelical fervor, and relied on the support of the resulting waves of ardent Methodists and Baptists who sought a strong national culture and morality.

There were Northern Democrats who opposed the expansion of slavery, and Southern Whigs who supported it. For most of Abraham Lincoln’s life, the question was whether or not slavery should be allowed to expand. Only the hard-core abolitionists looked on the plight of those already enslaved and demanded their liberty. One of the questions we must ask ourselves is whether Lincoln pushed emancipation forward—or was reluctantly pulled.

EARLY AND PRIVATE LIFE

By the time Abraham Lincoln was an adult, loss and grief were already familiar companions. Born in 1809 in Kentucky, Abraham Lincoln was raised by a father, Thomas—a tough, unforgiving man. Thomas was an orphan who had lost his father to an attack by indigenous Americans as white settlers pushed west. Illiterate but hardworking, Thomas eked out a living from the land and kept his family constantly in motion in pursuit of new opportunities. He and Abraham had a conflicted relationship. Tom was a serious and severe person, one whom we today might label abusive. There were also rumors that Tom was not, in fact, Abraham’s father. To young Abraham, Tom represented ignorance, brutality, lack of hope, and the near-bondage of a poor farming life. Suffice it to say, the two were not close. Years later, Abraham would not attend his father’s funeral.

Lincoln’s mother, Nancy Hanks Lincoln, was warm and loving. Yet the hard life took its toll on her. She died in 1818 of a “milk sickness” that also claimed other members of the family and left young Abraham without a mother at the tender age of eight. A year after his wife’s death, Thomas Lincoln remarried. Abraham’s new stepmother, Sarah Bush Johnston, was herself a mother of three. That meant more mouths to feed for a poor subsistence-farming family. But for Lincoln, it also meant a nurturing and caring parental presence in his life that his father would never have provided.

Abraham was the second of three children. Lincoln’s younger brother, Thomas, died in infancy, and his older sister, Sarah, died in childbirth at age twenty-one. His father frequently uprooted the family throughout his childhood—moving from Kentucky to Illinois, first to Perry County and then Macon County. By the time Lincoln was twenty-one years old, he had lost two siblings and a mother and had been forced to move and start over repeatedly.

The grinding misery and piercing tragedy of Lincoln’s dirt-poor farm upbringing drove him to escape that life. He left home as soon as he could and moved to New Salem, Illinois. He wanted to make money, and he wanted an America where men like him could decide their own fates instead of being trapped at the mercy of the harvest. He clerked in a store, worked on flat-bottom boats, and later opened an ill-fated shop with a friend, the failure of which left him in debt for years. He first ran for office at the age of twenty-three and was already an ardent Whig determined to foster a new economy of trade and business. In Abraham Lincoln: Redeemer President, Allen Guelzo convincingly argues that Lincoln viewed the independent farming life, which Thomas Jefferson elevated as the American ideal, to be quite nearly a form of slavery.

Growing up poor on a working farm did not offer much opportunity for education. As a young man, Lincoln received around four winters’ worth of school. But he was self-taught—an autodidact—and made up for lack of training with relentless curiosity and passion. He read everything he could get his hands on, from Shakespeare to poetry, self-improvement books, and newspapers. He taught himself law by poring over legal textbooks. His friends testified to his remarkable memory and the way the books he read shaped his character and language. One of those books—though he read it more as literature than as a devotional text—was the Bible.

Abraham Lincoln was raised in a rigidly Calvinist home. Calvinism is a strain of Protestant Christianity that historically has emphasized the total depravity of humankind and an implacable, almighty God who predestines some for salvation and the rest for eternal punishment. The faith system of Lincoln’s youth left little room for human will or free choice, emphasizing human helplessness before God—leaving Lincoln with a melancholy resignation that God had already determined in advance the course of human lives. Lincoln hated the dour religion of his younger years and mocked it repeatedly.

Lincoln read the Bible and could quote it with ease, but that did not make him a Christian. He became a skeptic and a doubter, perhaps even an agnostic or atheist. In his twenties, his friends talked him out of publishing a book dismissing many of the claims the Bible made about revelation, inspiration, miracles, and Jesus. He rarely attended church, though he was nominally a member of various congregations throughout his life. As his political career progressed, he faced pressure to speak more openly of his faith, and after his death, friends would defend his legacy by painting him as a consistent Christian in a time when that was expected. But it seems clear that Lincoln was a skeptic. In fact, he desperately wished he could overcome that skepticism and become more devout. He might even have suspected, with something between resignation and despair, that he was not someone God had chosen for salvation, even though he desperately wanted to believe.

Yet no American president has brought a religious interpretation to great world events the way Abraham Lincoln did. Influenced by Enlightenment ideas, Lincoln struggled with the notion of a personal relationship with God or Jesus as Savior. But the strict Calvinism of his youth shone through. He eventually developed a concept he termed the “Doctrine of Necessity.” He disparaged human free will and insisted that people act based on motives that are driven by their interests. In this sense all are predestined to the course they take. This is a fatalist and secularized version of Calvinism, without any loving and personal God. Yet eventually he seemed to recover at least some version of a doctrine of divine providence, in which God uses people for divine purposes in the world. Dark as it may seem, one can also see how such a belief system might help a young man cope with loss and a life of turmoil and physical labor—not to mention a great civil war.

Though full of stories and capable of a great sense of humor when called on, Lincoln nevertheless had a melancholic nature. One early bright spot in his life in New Salem was Ann Rutledge, whom he was determined to marry. He was devastated when she died, likely of typhoid fever, in 1835. Instead, he stumbled through a rocky courtship of Mary Todd, the daughter of a prominent and highly connected Whig family. He promised to marry her, before breaking the engagement after falling for another young woman. He remained a man who felt boxed in by forces outside his control and bore tremendous guilt over his initial failure to keep his promise to Mary. More out of obligation than anything else, he married her in 1842. The union was not an easy one.

Mary Todd grew up in comfort and was unprepared for the rugged life Lincoln could offer. Theirs was a rocky marriage that a friend described as “domestic hell.”4 Though she cared deeply about Lincoln, Mary Todd’s depressive nature did not mesh well with his natural melancholy. They would butt heads throughout their marriage, especially as she started having to play the role of the dutiful political wife. Together, they had four sons: Robert (1843–1926), Edward (1846–50), William (1850–62), and Thomas “Tad” (1853–71). Note the grievous losses of three sons at young ages. The Lincoln marriage was stormy, tumultuous, and sad, certainly no haven for Lincoln from the chaos brewing in the country around him.

VOCATION

Abraham Lincoln had two objectives in his early adulthood: escaping his father and the family farm, and winning political office. He was an ardent Whig and devoted follower of Henry Clay, focused on national improvements that he thought would create opportunity for upward advancement for young men like him. As a political figure, Lincoln was only a moderate success for most of his life. He was sufficiently popular in New Salem to be elected captain of a company of militiamen in the brief armed conflict known as the Black Hawk War and to be set up as postmaster by friends, earning a steady income. He lost his first race for the Illinois legislature but later won a seat and even took on a leading role among Whigs in office. He served one term in the US Congress before upholding his pledge to forgo reelection to give a turn to others. He lost a handful of political contests, including campaigns for a US Senate seat representing Illinois in 1854 and, most famously, in 1858. He lost that latter contest to Stephen Douglas, who for years in Illinois politics was Lincoln’s Democratic rival.

Lincoln did become a successful lawyer. Life on the legal circuit, surrounded by other ambitious and connected men, also helped his political fortunes. Though self-taught in law, he had an astonishing memory that served him well during piercing cross-examination, and he combined razor-sharp logic with dry humor to unsettle witnesses and win cases. He brought that same potent combination to a famous series of debates with Douglas in 1858 and to the speeches in the run-up to 1860 that put his name on the national map.

His tough childhood shaped him, but he became the man we remember today during the long years between 1832 and 1860. The poor farm boy became a small-town clerk, flatboat man, failed store owner, jack-of-all-trades postmaster, surveyor, lawyer, legislator, twice-failed Senate candidate, and die-hard Whig—then leader of a new Republican Party, surprise presidential nominee, unlikely president-elect with no popular-vote mandate, and eventually president of a nation on the brink of war before he was even sworn into office. To track Lincoln’s career during this time is to follow the evolution of his views on slavery, the leading issue of the era.

Lincoln was raised in an antislavery church in territories that did not allow slavery, so from the start he was unlikely to end up as a friend of the institution. He felt enslaved by his father and that way of life—an inadequate comparison, no doubt, but one that left him predisposed to empathize with slaves who sought liberty. He believed slavery to be morally wrong but, like many throughout history who did not carry the weight of injustice on their own shoulders, seemed content to let it die out slowly. For many years, he felt that the economic and social disruption that would result from immediate emancipation outweighed moral concerns.

This was a strategy of containment, not abolition. Even though abolition was a burgeoning national movement, Lincoln steered clear of bold postures. Opposed to bondage in general, he seemed to have little sensitivity to black slavery specifically. He even made the occasional comment expressing racial prejudice. Until late in his career, he expected that, if slavery were to be abolished, black Americans who had lived for generations in America would nevertheless return to Africa. He supported various colonization proposals.

The Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854 forced Lincoln to a new clarity. It would make the expansion of slavery contingent on popular vote, not bounded by the geographical limits of the earlier Missouri Compromise. Lincoln had long believed that slavery would die out if it had nowhere to grow. But if slavery were to expand, its exploitation of black labor would inevitably undercut white labor as well. The result would be a system in which both black Americans and whites like Lincoln would face exploitation from landed elites. Lincoln never favored slavery, but he opposed it with more vigor once expansion was a possibility.

The lawyer in Lincoln started reframing the case. After 1854, he began to talk about slavery as something the founders tolerated as a necessity for union, but only as a concession. He made appeals based on the founding American principles of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness, reinterpreting old ideas for the situation of his day. In a famous 1854 speech in Peoria, Illinois, these themes ring out:

Now congress declares this [policy of prohibiting slavery in new territory] ought never to have been; and the like of it, must never be again. The sacred right of self-government is grossly violated by it! We even find some men, who drew their first breath, and every other breath of their lives, under this very restriction, now live in dread of absolute suffocation, if they should be restricted in the “sacred right” of taking slaves to Nebraska. That perfect liberty they sigh for—the liberty of making slaves of other people—Jefferson never thought of; their own father never thought of; they never thought of themselves, a year ago.5

But to expound on such notions also required new moral arguments based on the humanity of enslaved people and every human’s aspirations to improve her circumstances. Abolitionism was still a bit extreme for cautious politicians, but there was a latent moral revulsion against slavery that Lincoln began to tap into and to find within himself. As he campaigned across Illinois between 1854 and 1858, his speeches more and more focused on the immorality of slavery and the inevitability of conflict over it:

“A house divided against itself cannot stand.” I believe this government cannot endure, permanently half slave and half free. I do not expect the Union to be dissolved—I do not expect the house to fall—but I do expect it will cease to be divided. It will become all one thing or all the other. Either the opponents of slavery, will arrest the further spread of it, and place it where the public mind shall rest in the belief that it is in the course of ultimate extinction; or its advocates will push it forward, till it shall become alike lawful in all the States, old as well as new—North as well as South.6

That House Divided speech, as it came to be called, on June 16, 1858, is one that may seem familiar and admirable to our ears but caused no small amount of grief to Lincoln in his lifetime. Critics seized on it and insisted that Lincoln was threatening violence if the South did not buckle. He was at great pains to clarify that the speech was descriptive, not prescriptive. He was articulating the reality as he saw it, one in which slavery must either win out or disappear, not, as opponents claimed, pushing for a path of violent conflict. Still, it likely cost him a seat in the US Senate. Even though he made himself a national name in his 1858 Senate debates with Stephen Douglas, he was forced to spend time defending that speech. His peers in the state legislature, which still had authority to pick senators at that time, chose Douglas instead.

Lincoln had just lost two elections in a row, and yet the way he evoked both moral principle and American values to denounce slavery drew national notice. In 1860, a handful of famous and well-known politicians vied for the presidential nomination of the new Republican Party. With the Whig Party in a state of collapse and the Democrats split between Northern and Southern wings over slavery, all assembled at the Republican convention knew that their candidate stood a surprising chance of winning the presidency that year. They had as options men of long-held, fervent principle; men with years of governing experience; and politically powerful, well-connected men. They chose Abraham Lincoln.

In the end, he was second choice of most people—a man with a sufficient track record against slavery, from his debates with Douglas and a famous speech at Cooper Union, but not one who seemed too radical. On election day 1860, he was the first choice of just enough people, winning the presidency with 180 electoral votes but only 40 percent of the vote. Southern states began seceding even before he was sworn in, and the American Civil War officially began a few months after.

There are enough accounts of that war to fill endless libraries. What interests us is the continuing evolution of a man who seemed shockingly unqualified for the presidency into a moral leader we remember today. Part of the explanation lies in the crushing weight on his shoulders after taking office. In the crucible of war, the immorality of slavery became clearer and clearer to him. What began as a fight to preserve the Union became, in his mind, a war over slavery. But that is not where he started. Consider his first inaugural address:

I have no purpose, directly or indirectly, to interfere with the institution of slavery in the States where it exists. I believe I have no lawful right to do so, and I have no inclination to do so. Those who nominated and elected me did so with full knowledge that I had made this and many similar declarations and had never recanted them; and more than this, they placed in the platform for my acceptance, and as a law to themselves and to me, the clear and emphatic resolution which I now read: “Resolved, That the maintenance inviolate of the rights of the States, and especially the right of each State to order and control its own domestic institutions according to its own judgment exclusively, is essential to that balance of power on which the perfection and endurance of our political fabric depend; and we denounce the lawless invasion by armed force of the soil of any State or Territory, no matter what pretext, as among the gravest of crimes.”7

Perhaps he was so laser-focused on reassuring Southern states and avoiding war that he was willing to put slavery aside. Or perhaps it had not yet become the life-changing moral cause that grasped the last few years of his life.

In a private and meaning-laden “Meditation on the Divine Will,” written in September 1862, Lincoln tries to find meaning in the carnage around the country, now nearly two years into the Civil War. Sounding quite Calvinist, he begins with the premise that God’s will prevails. But what is God’s will in relation to this terrible war? That leads him to muse, “In the present civil war it is quite possible that God’s purpose is something different from the purpose of either party—and yet the human instrumentalities, working just as they do, are of the best adaptation to effect His purpose. I am almost ready to say that this is probably true—that God wills this contest, and wills that it shall not end yet.”8

God could end the war, Lincoln suggests, and yet has not. If one of the two sides is in the right, then why would God not reward them with swift victory? God must have another, inscrutable plan. God had put him in office. God had taken two of his children and the sons of countless other fathers and mothers. “The real heart of Lincoln’s personal religious anguish,” Allen Guelzo maintains, was “the deep sense of helplessness before a distant and implacable judge who revealed himself only through crisis and death, whom Lincoln would have wanted to love if only the Judge had given him the grace to do the loving.”9

As Lincoln pondered such notions, he faced the daily pressure from abolitionists to act amid the ongoing failure of the larger and better-supplied Union Army to win the war. He knew, on a strategic level, that slavery united the Confederacy and fed its cause. Then there were black Americans themselves, who sought refuge behind Union lines whenever they could and in many instances returned to fight bravely as Union soldiers. Surely, they were not fighting to preserve the prewar status quo.

Perhaps the answer was right in front of him. Perhaps what God demanded, the true reason the Almighty permitted such bloodshed, was liberty for the enslaved. According to Lincoln’s secretary of the treasury, Salmon Chase, Lincoln offered a promise to God sometime in the fall of 1862. Out of character as it may seem, especially for a man like Lincoln with an impersonal view of the divine and such public doubts, Chase was likely telling the truth. Lincoln, it seemed, had made a private vow to God: if you give us victory, I will free the slaves. When he shared this decision with his cabinet, he faced opposition. Some feared it would rally the Confederates; others thought it might be seen as the desperate measure of a losing side.

He agreed to delay but would not be dissuaded. At the first sign of positive news from the front, he announced the Emancipation Proclamation. Issued January 1, 1863, it was a limited document that freed only slaves in Confederate states and only during the course of the war. It was a signal of unmistakable intent, though, an intent Lincoln articulated more and more in his public speeches. By fall of 1863, in his now-famous, then-overlooked Gettysburg Address, he cast the war as leading to a rededication to America’s founding ideals. The sacrifice of those who gave “the last full measure of devotion” would inspire those who remained to wipe the stain of slavery off the founding egalitarian ideal.10

Before long, Lincoln had thrown his weight behind a proposed constitutional amendment to ban slavery—not based on wartime powers, not based on seizing rebel property, not only in states that had seceded, but nationally, permanently, and unequivocally. Some members of his own cabinet opposed the move, and passage through the House was in doubt down to the final days. It took intense political horse-trading to get it done. Lincoln now felt such moral urgency that nothing would stand in his way. “The greatest measure of the nineteenth century,” the radical Republican Thaddeus Stevens declared of the constitutional amendment, “was passed by corruption, aided and abetted by the purest man in America.”11

In Lincoln’s second inaugural address, quoted above, all the threads come together. The great and horrid bloodletting is recast as the price to be paid for 250 years of slavery. Blood drawn by sword for blood drawn by lash: a terrible punishment, one that seems simultaneously just, cruel, and ultimately insufficient. Lincoln saw the end of that bloody war. He did not live to see the Thirteenth Amendment ratified. If he had lived, perhaps he would have prevented the eventual Republican betrayal of freed persons that ended Reconstruction and left millions at the mercy of Jim Crow and the lynching tree. But on Good Friday, 1865, an assassin’s bullet struck down Abraham Lincoln. A few hours later, early Saturday morning, he took his last breath.

LEGACY AND CRITICISM

It would be fair to say that Abraham Lincoln was well liked for most of his life until, for a few years at the very end of his days, he was both despised and beloved in equal measure. What may come as a surprise is that he was despised well before he was loved. Many in the South needed to hear only of his opposition to slavery to dismiss him. But Northerners did not line up uniformly behind him either, even after the nation was at war. Some felt his intransigence and unnecessary provocations led to a war that might have been avoided. Abolitionists, meanwhile, questioned his devotion to their cause, and free black men and women wondered about his moral compass. In the early days of the war, almost all, regardless of political persuasion, doubted his ability to lead the Union to victory.

Part of the initial bias was related to his style and demeanor. He had a rough-hewn look and a country self-presentation, full of frontier stories and folksy wisdom. From the start, he was criticized for not having the appearance and civilized bearing of a president. Lincoln managed to distinguish between the helpful criticism and the unhelpful. Knocks on his style he shrugged off with that same folksy attitude—after all, he had been through worse. Critiques of his leadership, on the other hand, he appears to have evaluated for how they might help him improve.

The undercurrent to all of this was a life of loss and grief. It left Lincoln grounded and always able to differentiate between the important and the ephemeral. Small ups and downs pale in comparison to the loss of a parent or a child. He also seemed to have developed confidence that he could muddle through and emerge, still standing, on the other side of great turmoil. At the same time, he felt deep melancholy. Throughout his life, he would fall into periods of what we would today call depression. His life shows that great leaders are not immune to mental illness; greatness, rather, flows out of acknowledging it and responding. Lincoln’s experience in darkness helped him guide the country through its own night.

Lincoln also had integrity. He was tactful and strategic about his image, as all politicians are. But he seemed unwilling to be artificial to impress audiences. He was a doubter in a religiously minded party in a devout country. It would have been all too easy to heap up empty words—after all, he had been reading the Bible his entire life—and win over those who called him an atheist or agnostic. We live in an era when public pronouncements of deep faith are so common that they have almost lost their meaning. We know that in many cases, we are being deceived. Rarely if ever does one sense that Lincoln faked certainty in matters of faith in order to win admirers.

Lincoln seemed altogether blind to the secession threat during his presidential transition and first months in office. Too often, there is a temptation to look back and see Lincoln as a master strategist playing chess when all others were playing checkers. The fairer portrait acknowledges that despite his gifts he was unprepared for the responsibilities he assumed. He seemed convinced in the early months that Southern states would never go so far as to secede, and so failed to take steps to prevent it or prepare for the aftermath.

Once war was announced, he skewed wildly between deferring too greatly to his generals and micromanaging them. One of those generals, George McClellan, was so famously reluctant to attack that Lincoln once wrote him to ask whether he could borrow the Army of the Potomac if McClellan did not intend to use it. Their tumultuous relationship continued through 1864, when the now-former general McClellan ran for president against Lincoln. In summary, Lincoln’s first year or more in office gave little sign that he was equipped for the job. Perusal of a shelf of books on the American Civil War—or five minutes with your average Civil War buff—will demonstrate that Lincoln’s management of the war and the general Union strategy are matters of fierce debate even today.

During his time in office, Lincoln suspended habeas corpus and limited press freedom. Under the cover of emergency wartime measures, he took steps that critics then and now deem undemocratic, even dictatorial, and resulted in the arrest of more than thirteen thousand people. He was accused of presiding over a massive centralization of power in the hands of the federal government and trampling the Constitution of the United States. Are such steps ever justifiable? Only to save the Union? Only to emancipate millions of enslaved people? The sole clear conclusion is that leadership requires taking the risk of making difficult, unpopular, even wrong decisions and bearing the consequences.

We have noted already that Lincoln struck an unhappy balance between abolitionists and Republican conservatives. There is a temptation to make an idol of centrism. But in this case, one of the poles was toleration of slavery and the other liberty for millions of human beings who had lived in unspeakably cruel bondage for generations. Lincoln was quick to see threats to fellow white laborers from expanding slavery and slow to see the image of God in the black faces of the already enslaved. Yet there is also a temptation to dismiss all those who did not arrive at the right answer at the earliest possible moment. A respectful engagement of Lincoln’s life mournfully acknowledges his lateness. Then it must recognize that he made abolishing slavery his and the nation’s moral cause, even as some told him it was foolish, and millions more were willing to fight and die to preserve it.

How, then, should we remember Lincoln today? It likely depends on your own context. Lincoln might be the great emancipator—or the man who had to be pushed and pulled into opposing an abject evil. He might be the man who precipitated a needless war with his radical attacks on state sovereignty—or the leader who risked war to preserve a union. He might be the visionary leader who saw the future need for a powerful national government, banking, and infrastructure—or the uncritical lawyer for big railroads who helped industry concentrate political power. To come to an understanding of Lincoln’s life requires us first to look at our own lives, assumptions, and beliefs. We study moral leaders to learn about ourselves.

One of the reasons we include Lincoln as a moral leader is the way he finally centered slavery as the defining moral issue at stake in the Civil War. Lincoln did so with a fantastic work of public theology: part redemptive, part reconciling, all distinctively Calvinist. “Providence was what allowed him to overrule the moral limitations of liberalism,” writes Allen Guelzo. “To do liberalism’s greatest deed—the emancipation of the slaves—Lincoln had to step outside liberalism and surrender himself to an overruling divine providence whose conclusions he had by no means prejudged.”12 To respect human self-determination requires reckoning with human determination to dominate others. Doing so, for Lincoln, required providence.

In the end, Lincoln produced a theological interpretation of the war, slavery, and its meaning for one nation’s soul. He drew on a major strand of America’s religious heritage to make sense of the war in such a way that America could move forward after the war. The war was, for Lincoln, the divine punishment for a nation—North and South—that had tolerated and embraced the degradation of slavery. Mature, chastened, more religious than political, this recasting came from one who wished for faith he never seemed to be able to embody, one whose doubts and uncertainty fit a national mood, one whose belief in providence helped the Illinois flatboat man chart a course through rocky waters.

Abraham Lincoln’s life and work offer a number of important lessons about moral leadership:

- Character is formed in suffering and struggle. If Lincoln had never faced tragedy and loss, the Civil War might have overwhelmed him. The hard moments in your life are an opportunity to learn about yourself. Events, no matter how tragic, can help you discover unknown gifts and new sources of energy and strength.

- Personal ambition can drive us to great things. We distrust ambitious people even as our culture rewards and honors ambition. We should distinguish between personal ambition that leads to selfish acquisition of wealth and power, and ambition that drives people to positions where they can promote justice and deliverance.

- Convictions must be allowed to grow. We admire people of strong convictions, and we should. We must give even more admiration to those who manage to hold strong convictions while questioning them, reconsidering them, changing them, and fitting them to tough and different situations they face.

- Theology has a role in public life. There are endless debates about the roles of the church and state and the relationship between the two. But to remove theology and any God-talk from public life can leave people without a frame of reference to understand history, what is at stake, and what to do next.

- Be resilient, never give up, and learn from mistakes. After years of failed attempts at political office, including two losing Senate races, Lincoln pondered withdrawing from politics—mere years before he became one of the most admired presidents in American history.

- Leadership always provokes criticism. It is impossible to be in a position of leadership without receiving criticism. Leaders rise or fall based on how they respond to critiques and what lessons they are willing to learn from those who critique them.

In the decades after the Civil War, millions of black Americans tasted both freedom and a bitter backlash. Reconstruction was abandoned, and Jim Crow became the law of the land. In the process, the memory of the war was tailored to fit the needs of the time. Among white Americans, a myth of the Blue and the Gray arose from attempts to make sense of the tragedy and heal the divide. This myth deemphasized slavery and cast the Civil War as a regrettable yet honorable contest between equals who fought for their homes and traditions. This myth united white Americans while ignoring the formerly enslaved. Alongside this myth, there has been a sectional approach to remembering the war that casts it either as a fight to end Southern backwardness or the result of unchecked Northern aggression. It is easier for white Americans to remember the war as a battle over states’ rights or as the fault of other people’s prejudice than to make a full confession of national complicity in the horrors of slavery.

That was never Lincoln’s approach. Lincoln called the nation to confession. He himself had never owned slaves and could have pointed to his hardscrabble upbringing to insist that he never benefited from slavery. Instead, he declared himself and all Americans complicit in a great evil and sought to bear the consequences. If he had lived, perhaps such a confessional attitude might have saved Reconstruction and lanced the boil of racism that still thrives today. Sadly, his life was cut short—but his memory still speaks.

DISCUSSION QUESTIONS

- What do you make of the profound suffering that Abraham Lincoln experienced in his life? How did it shape him as a leader?

- Would you describe Lincoln as a person of faith? What kind of faith? What role did it play in his life and presidency?

- Lincoln gave some of the most important speeches in American history. Name one that you find especially significant, and discuss reasons why.

- Settle the issue once and for all: for Abraham Lincoln, was the Civil War about ending slavery?

- What role did Lincoln’s family life, from childhood to his relationship with Mary Todd, play in his professional life?

Donald, David Herbert. Lincoln. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1995.

Guelzo, Allen C. Abraham Lincoln: Redeemer President. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2003.

Keneally, Thomas. Abraham Lincoln: A Life. New York: Penguin, 2003.

Lincoln, Abraham. The Language of Liberty: The Political Speeches and Writings of Abraham Lincoln. Edited by Joseph R. Fornieri. Washington, DC: Regnery, 2009.

Lowenthal, David. The Mind and Art of Abraham Lincoln, Philosopher Statesman. Lanham, MD: Lexington, 2012.

White, Ronald C., Jr. Lincoln: A Biography. New York: Random House, 2009.

1. Allen C. Guelzo, Abraham Lincoln: Redeemer President (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2003), 65.

2. Abraham Lincoln, “Second Inaugural Address,” in The Language of Liberty: The Political Speeches and Writings of Abraham Lincoln, ed. Joseph R. Fornieri (Washington, DC: Regnery, 2009), 712.

3. Lincoln, “Second Inaugural Address,” in Language of Liberty, 712.

4. Guelzo, Abraham Lincoln, 112.

5. Lincoln, “The Repeal of the Missouri Compromise and the Propriety of Its Restoration,” in Language of Liberty, 153.

6. Lincoln, “A House Divided,” in Language of Liberty, 224.

7. Lincoln, “First Inaugural Address,” in Language of Liberty, 581–82.

8. Lincoln, “Meditation on the Divine Will,” in Language of Liberty, 798–99.

9. Guelzo, Abraham Lincoln, 446.

10. Lincoln, “The Gettysburg Address,” in Language of Liberty, 801.

11. Guelzo, Abraham Lincoln, 401.

12. Guelzo, Abraham Lincoln, 447.