nine

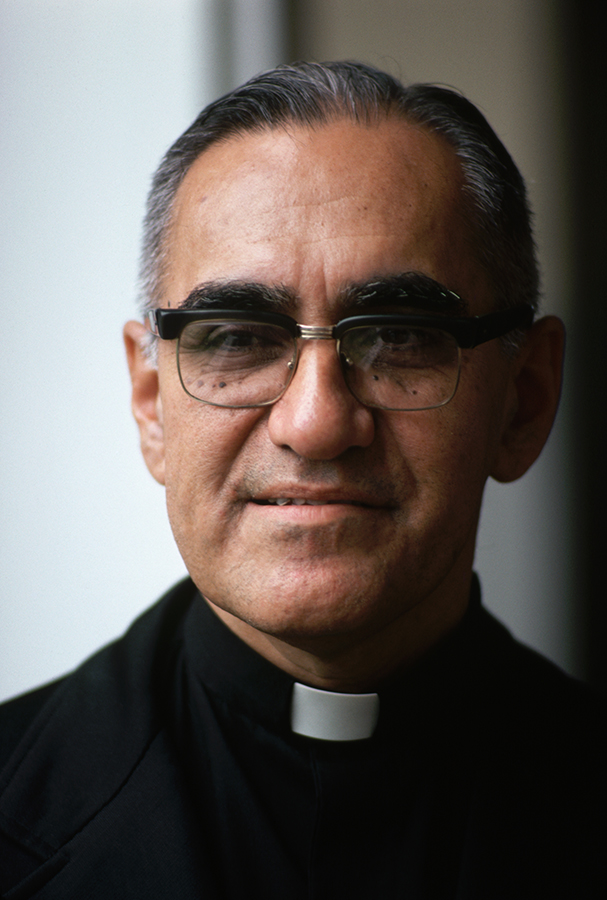

Oscar Romero

1917–80

1917 (Aug. 15): Born in Ciudad Barrios, El Salvador.

1918 (May 11): Baptized in Ciudad Barrios.

1930: Enters minor seminary in San Miguel.

1937: Studies at major seminary in San Salvador, then Pio Latino College in Rome. Father dies.

1938–41: Studies in Rome at Pio Latino College and Gregorian University.

1939 (Sept.): World War II begins.

1941: Receives theology degree.

1942 (Apr. 4): Ordained as a priest in Rome.

1942: Begins doctoral studies in ascetical theology.

1943 (Aug.): Leaves Rome for El Salvador; detained in Cuba.

1943 (Dec.): Arrives in El Salvador.

1944 (Jan. 11): Celebrates first Mass in Ciudad Barrios.

1944–67: Appointed as parish priest in Anamorós; shortly after, begins 23 years as diocesan secretary and chaplain in San Miguel.

1945: World War II ends.

1953: Undertakes Spiritual Exercises of St. Ignatius Loyola.

1961: Mother dies.

1962–65: Second Vatican Council transforms church’s posture toward the world.

1967: Becomes secretary of the Salvadoran Bishops’ Conference. Befriends Jesuit priest Rutilio Grande. Receives title “monsignor” after 25 years ordained.

1968: Attends Medellín Conference of CELAM.

1970 (June 21): Installed as auxiliary bishop of San Salvador.

1971: Edits archdiocesan newspaper Orientación. Fr. Rutilio Grande becomes parish priest in Aguilares.

1972: Colonel Arturo Molina becomes president despite his election loss.

1974 (Dec. 14): Installed as bishop of Santiago de Maria.

1975 (June 21): Tres Calles massacre; writes letter of protest to president.

1975 (July 30): Salvadoran military kills 40 students; Romero chides those who occupy San Salvador Cathedral in protest.

1976 (Aug. 6): Preaches against so-called new Christologies in San Salvador.

1976 (Nov. 28): Issues pastoral letter condemning treatment of farmworkers.

1977 (Feb. 20): Installed as archbishop of San Salvador; General Carlos Humberto Romero (no relation) announced as next president after fraudulent election.

1977 (Feb. 28): Dozens killed protesting presidency.

1977 (Mar. 12): Fr. Rutilio Grande and two companions assassinated.

1977 (Mar. 20): Conducts single open Mass before national cathedral in Grande’s honor.

1977 (Mar. 26): Meets with Pope Paul VI.

1977 (Apr. 10): Publishes first pastoral letter, The Easter Church.

1977 (May 11): Fr. Alfonso Navarro assassinated.

1977 (May 19): National Guard attacks Aguilares.

1977 (June 19): National Guard allows Romero into Aguilares to celebrate Mass.

1977 (June 21): Paramilitary group “White Warrior Union” threatens to kill any Jesuits remaining in country within 30 days.

1977 (July 1): Refuses to attend presidential inauguration in protest.

1977 (Aug. 6): Publishes second pastoral letter, The Church, the Body of Christ in History.

1977 (Nov. 24): Government passes Law for Defense of Public Order.

1978 (Feb. 14): Awarded degree from Georgetown University for defense of human rights.

1978 (June): Second visit with Pope Paul VI.

1978 (Aug. 6): Issues third pastoral letter, The Church and Popular Political Organizations. Pope Paul VI dies.

1978 (Oct.): Karol Wojtyla installed as Pope John Paul II.

1978 (Nov.): Nominated for 1979 Nobel Peace Prize. Another priest murdered under suspicious circumstances.

1978 (Dec. 14): Argentine archbishop Antonio Quarracino visits to investigate situation.

1979 (Jan. 20): Security forces kill Fr. Octavio Ortiz and four teenagers.

1979 (Jan. 22): Arrives at Puebla CELAM meeting.

1979 (May 7): Meets with Pope John Paul II.

1979 (May 8): Police forces kill 25 and wound 75 in front of the national cathedral.

1979 (June 20): Fr. Rafael Palacios assassinated.

1979 (July 19): Sandinistas overthrow Somoza dictatorship in Nicaragua.

1979 (Aug. 4): National Guardsmen assassinate Fr. Alirio Macías.

1979 (Aug. 6): Issues fourth pastoral letter, The Church’s Mission amid the National Crisis.

1979 (Sept. 29): Soldiers kill a Romero friend, peasant leader Apolinario Serrano.

1979 (Oct. 15): Military coup overthrows General Carlos Humberto Romero and installs new junta.

1980 (Jan. 2): Civilian-military government collapses; military forms new junta.

1980 (Jan. 22): 20 killed and 120 wounded on anniversary of 1932 peasant uprising.

1980 (Feb. 2): Visits Belgium to receive honorary degree from Catholic University of Louvain.

1980 (Feb. 17): Writes open letter to US president Jimmy Carter pleading for end to US aid for security forces.

1980 (Feb. 18): Bomb destroys Salvadoran church radio station, YSAX.

1980 (Mar. 7): Criticizes government efforts at reform via repression.

1980 (Mar. 9): Bomb discovered near altar before Romero homily.

1980 (Mar. 10): Remaining center-right civilian members of government resign to protest right-wing assassination of a colleague.

1980 (Mar. 23): Delivers sermon demanding that army cease killing and that soldiers defy orders to hurt civilians.

1980 (Mar. 24): Assassinated conducting Mass.

Something changed inside Oscar Romero on the night of March 12, 1977, looking down at the body of his friend Rutilio Grande. Grande, a Jesuit priest who had presided at the installation of Romero as auxiliary bishop, had gone on to become a beloved parish priest who allied himself with the suffering poor of his church. A few hours earlier, Grande had been driving in a car with an elderly man, a sixteen-year-old boy, and three small children, when a hail of gunfire fell on the vehicle. The bullets, flying from multiple directions, killed all but the three children. The priest was struck twelve times and died instantly. Grande was the first priest murdered in the wave of violence that preceded El Salvador’s thirteen-year civil war beginning in 1980. He would not be the last.

Overseeing the church of El Salvador at the time was Romero, a conservative Catholic leader whose appointment as archbishop had been a cause for celebration among the rich oligarchy. Their hopes would be dashed. In the wake of Grande’s killing, Romero began speaking out against illegal killings, preaching on behalf of the poor, and turning the potent resources of the church to the aid of the oppressed. Within three years, he was the face of the moral resistance to the toxic alliance of the military and the rich elite in his homeland. Soon after, he joined his friend Grande in suffering the ultimate cost of standing with the poor.

Romero always downplayed the idea that he experienced a conversion. But most biographers and theologians who have studied Romero believe there was a point when he chose a new path. Jon Sobrino, a young priest who was in the room that night and went on to become one of the most prominent theologians from the Americas, pinpoints the moment Romero saw Grande dead before him. Afterward, the archbishop conducted Mass. He sat for hours with the campesinos, the peasant poor, and listened to their stories of exploitation, poverty, abuse, and violence. Then he went about the work that would make him a beloved figure, a moral leader, and a heroic martyr.

HISTORICAL CONTEXT

In 1932, poor peasants in El Salvador decided to fight back. For too long, a handful of elite landowners and their allies had walked all over the working farmers of the small nation hugging the west coast of Central America. Colonial occupation and concentrated political power had left a small group of people with most of the productive land, control of the nation’s banks, and a firm grip on the government. The campesinos could barely afford to feed their families. So the campesinos fought back—and the military regime retaliated. In an event that would come to be known as La Matanza, literally “The Slaughter,” the military killed thirty thousand people and crushed the rebellion.

For the next fifty years, military governments brutally ruled El Salvador. At risk of oversimplification, it is worth noting three important actors in this decades-long drama. The first was the military and allied police forces. A center-right conservative force, the military sometimes promoted measured reforms, often to forestall revolution. Its top priority, though, was preserving order and maintaining a grip on power. The rural-based National Guard had few qualms about putting down demonstrations with violence, and the military regime created and actively supported paramilitary organizations. These armed squads had military-grade weapons and organization but were not part of official state forces.

The second group included far-right organizations and the landowners they represented. A small group of wealthy elites—an oligarchy—shared power with the military and controlled most of the land, industries, and wealth of the nation. This tiny fraction, less than 1 percent, of Salvadorans owned more than 40 percent of the land—especially the most productive farmland that produced coffee, sugarcane, and cotton for export to rich nations such as the United States. They also controlled banks and industry and, lacking any check on their power, freely exploited the poor of the country. Outright corruption under the guise of capitalism kept elites in charge and denied campesinos any hope for improvement. Elites funded far-right political groups and paramilitary organizations that supported their interests, often with violence and terror.

The third group consisted of the broad mass of the people, including campesinos and the smaller group of urban laborers. They worked seasonal jobs for low pay, and the lucky ones scraped a livelihood out of small plots of land. Roughly one-third of poor families had no access to fresh water, two-thirds of rural women gave birth without medical care, and almost three-quarters of rural children were undernourished.1

Attempts to band together for better pay or conditions met with violent crackdowns. Groups such as FECCAS (Federación Cristiana de Campesinos Salvadoreños, Christian Federation of Salvadoran Peasants), a Christian-inspired rural organizing movement, joined forces with the Union of Rural Workers (Unión de Trabajadores del Campo, UTC), urban laborers and the poor, and students and teachers. Such leftist organizations usually began with struggling people uniting for collective economic power. They became more militant in response to government repression. Many became political organizations that sought representation in government and reforms including land redistribution, nationalization of corrupt industries, and protections for the poor. Some leftist groups turned to violence and found conditions ripe for recruiting supporters.

Oscar Romero lived his last decades against the backdrop of global maneuvering between Soviet communism and Western democratic capitalism. Though the capitalist West and Communist East had united to defeat Nazi Germany and the Axis powers, victory opened the door to immediate rivalry. The postwar era marked the beginning of the Cold War between the United States and Russia—a time of heightened tensions, nuclear threats, and simmering conflict.

The United States government conducted Cold War foreign policy based on the “domino theory,” the idea that if one nation fell to communism, so would another, until, like a row of dominos, entire continents would fall. Western governments intervened militarily and with weapons sales in order to prop up anti-Communist governments around the world. Assuming that populist movements were Communist fronts, the US usually sided with right-wing forces. Populist movements also threatened US neocolonial economic interests, especially in Latin America, where the export economy served the US rather than local needs. At the School of the Americas in Fort Benning, Georgia, the United States trained foreign military forces to fight against communism. In practice, many who received training did not distinguish between Communists and poor people’s movements, and some used US training and weapons to commit horrific atrocities.

The Catholic Church had been of two minds from the moment it first gave conquistadores papal approval to claim Central and South America for Spain and Portugal. The official church, with its land holdings and senior clergy from Europe, was a dedicated ally of colonial governments and the new aristocracy. At the same time, Jesuit and Franciscan missionaries who lived and worked among the people often became the fiercest defenders of the enslaved, indigenous peoples, and the rural poor. In the 1960s and 1970s, this divide resurfaced again in deeply Catholic Latin America in the form of liberation theology.

Young Romero typified the traditional teaching when he told his flock, in the words of one campesino, “that God knew what He was doing by putting us last in line, and that afterwards we would be assured a place in heaven.”2 In contrast, liberation theology asserts God’s “preferential option for the poor.” It holds that the church should actively take the side of the poor against powerful interests and repressive governments. Liberation theology adopted the teaching methods of Brazilian educator Paulo Freire. Instead of listening to priests’ theological justifications for poverty, the people met in small groups, called comunidades de base or “base communities.” They shared experiences, identified the systems that kept them poor, and shared their insights with clergy.

Because liberation theology leaned on class-based methods of social analysis borrowed from Karl Marx, conservative Catholics viewed it with suspicion. Rome suppressed its supporters and punished priests who openly engaged in politics. It nevertheless spread quickly and inspired millions of impoverished people. In El Salvador, it produced sharp divisions. Many Jesuits embraced action on behalf of the poor and despised, to the point where one popular right-wing slogan urged, “Be a patriot, kill a priest.”3 On the other side, defending a more traditional view of the church, was Oscar Romero. At least, that is, until March 12, 1977.

EARLY AND PRIVATE LIFE

Oscar Arnulfo Romero y Galdámez was born on August 15, 1917, in Ciudad Barrios, a small town in the east of El Salvador. He was the second of eight children, six boys and two girls, born to Santos Romero and Guadalupe de Jesús Galdámez. His father, Santos, worked as a telegraph operator and postmaster and cultivated a small plot of land. Oscar’s mother, Guadalupe, cared for the children. Their home had no electricity, and Romero knew nothing of luxury. They rented the upstairs floor to tenants, forcing Romero’s mother to do many household chores outside in the rain. She was ill repeatedly and eventually lost the use of one arm. Santos, meanwhile, lost his land to an exploitative moneylender.

It is challenging to trace the influence of Romero’s family, perhaps because he had matured so much before his pivotal years. He adored his mother, and she left Ciudad Barrios to live near her son after he entered the priesthood. Romero seemed to have a different relationship with his father. Though Santos was not particularly pious, he taught his children to pray and instilled in Oscar a love of music. But the elder Romero wanted his son to learn a trade and frowned on Oscar’s choice of the priesthood. Santos died in 1937, while his son was still at seminary.

Young Oscar bore a striking physical resemblance to his mother and seemed to take after her personally as well. He was shy, quiet, and kind—qualities that stayed with him all his life. He later described himself as “meek.”4 He suffered a severe illness as a child, though we know little about it. A serious child who never broke the rules, he was also one of the most devout and pious local children. He was constantly in prayer, going well beyond the practices taught him by his father and mother. When he was thirteen years old—and apprenticed to a carpenter at the time—a bishop asked him what he wanted to do with his life. “I would like to be a priest!” the young man replied. “You will become a bishop,” the older man predicted.5

Romero’s early piety evolved into an intense spiritual regimen. Like Gandhi but never to his degree, Romero was an ascetic. He denied himself indulgences and followed a demanding, even harsh, rule of life. He maintained an intense prayer schedule, often rising in the middle of the night. He also underwent days of fasting and long periods of silent prayer and meditation, and, later, he worked through the Spiritual Exercises of St. Ignatius Loyola. As all Roman Catholic priests, Romero was celibate.

Romero went to public school as a child before pausing his academic education to follow his father’s wishes and learn carpentry. In 1930, after deciding he wanted to be a priest, he entered the minor seminary in San Miguel, El Salvador. He studied briefly at the major seminary in San Salvador and then departed for Pio Latino College in Rome. He continued his education at Pio Latino and then Gregorian University. In 1942, he began graduate studies at Gregorian, selecting as his subject the ascetical theology of sixteenth-century Spaniard Luis de la Puente.

“I’ve been thinking of how far a soul can ascend if it lets itself be possessed entirely by God,” he wrote as he began work.6 Such all-encompassing surrender to God defined his life. Early on, he followed de la Puenta in his focus on internal transformation and growing into holiness. Coming of age before Vatican II, he joined his contemporaries in seeking to protect the church from modern skepticism, states, and ideologies. Only later did his mystical spirituality turn outward toward relationships and the suffering around him.

Biographers have noted that Romero suffered from loneliness, estrangement, anxiety, obsessive-compulsive tendencies, and what his spiritual director described as scrupulosity. He laudably sought psychotherapy throughout his life. Damian Zynda, while noting that a sure diagnosis would be inappropriate, believes Romero suffered from Obsessive-Compulsive Personality Disorder, with its “preoccupation with orderliness, perfectionism, and personal and interpersonal control, at the expense of flexibility, openness, and efficiency.”7 Zynda says we can see some of these symptoms in Romero’s obsession with careful lists and agendas and his insistence on perfecting himself and those around him.

During the first half of his life, guilt often troubled the young priest. He seemed to imagine God as a strict and unforgiving judge constantly disappointed in Romero’s sinful errors. He sought to perfect himself through self-denial and to seek absolution through self-punishment. As he rose through a rapidly changing church, he found himself overwhelmed, lonely, and depressed. To his credit, he sought the advice of a spiritual director and a psychoanalyst. His transformation came as he began to see the freely flowing love and compassionate grace of God.

Romero was ordained as a priest in Rome. Despite receiving his degree in 1941, he had been too young for ordination and had to wait a year. By 1943, World War II made it untenable for him to continue his graduate studies in Rome. In August, he set sail for El Salvador. Romero and his traveling companions were detained in Cuba for three months—under suspicion because they were traveling from Axis power Italy. Arriving home in December, the young priest celebrated his first solemn Mass in Ciudad Barrios. It was the beginning of a career in El Salvador that took him to the pinnacle of the church.

VOCATION

The first decades of Oscar Romero’s career bear little resemblance to the tumultuous last three. Romero kept his head down and remained focused on the church and his core priestly duties. He was appointed parish priest in Anamorós in 1943 but quickly left the post to become the diocesan secretary in San Miguel. For twenty-three years, he served there and as chaplain of the small chapel of San Francisco. His radio programs on Catholic life and spirituality also left him well-known throughout the countryside.

The Vatican II conference unleashed sweeping changes and provided momentum to those who had long chafed at the church’s alliance with conservative powers. Events came to a head after the 1968 meeting of the Latin American Episcopal Council (Consejo Episcopal Latinoamericano, CELAM) in Medellín, Colombia. There the Latin American bishops produced documents committing the church to standing with the poor against military violence and economic impoverishment. Romero attended Medellín but felt unsteady in the new church. He preferred the traditional liturgy and practice, and was wary of change.

Romero demanded charity from the rich and offered hope of an afterlife to the poor but saw danger in the church taking sides in political disputes. After he became auxiliary bishop and editor of the archdiocesan newspaper Orientación, he used his platform to attack Jesuits whom he described as preaching Marxism. In person, the timid Romero became obstinate and flustered at any political talk. He was aghast at priests who openly called government elections fraudulent and labeled them subversives. As late as 1976, Romero was still criticizing these trends, even preaching against so-called new Christologies, but winds of change were sweeping through the man too. He had been spending more time in spiritual direction and on retreat, and befriended a Jesuit, Father Rutilio Grande, who presided at his installation as auxiliary bishop. In 1974, he was reassigned and became bishop of Santiago de Maria. Suddenly, Romero was no longer running in the same social circles as the powerful and wealthy. Now he was the leader of a flock of the poor and desperate. Listening to their stories of hardship cracked his shell. In his homilies and pastoral letters, he began to reflect on their concerns and denounce the ill treatment of farmworkers.

In June 1975, protesters blocked roads in Romero’s diocese to call attention to unjust conditions. The National Guard responded by entering the Tres Calles neighborhood and killing six relatives of the organizers, none of whom had been involved. Romero arrived the next morning and heard how National Guardsmen had bound, machine gunned, and hacked their victims with machetes. Horrified, he visited the National Guard barracks to register a complaint and later submitted a report in a private letter to the president of El Salvador, a personal acquaintance. It was a typically conservative response to such an outrage—made in private, trusting the authorities to respond—but also evidenced his slow transformation.

The leader of the church in El Salvador, Archbishop Chávez of San Salvador, had invited liberation theologians into the country and butted heads with Romero, his second in command as auxiliary bishop. It was Chávez who transferred Romero to Santiago de Maria. The oligarchy and military thus saw Chávez’s 1977 retirement as the perfect opportunity to pull a thorn from their side. Auxiliary Bishop Arturo Rivera y Damas, who shared Chávez’s leanings, was in line to succeed him. But Rome tended to see all populist movements as antichurch Communist fronts and favored, instead, a conservative, government-friendly pick: Oscar Romero.

Romero was installed as archbishop of San Salvador on February 20, 1977, in a surprisingly simple ceremony. The assassination of Fr. Grande came within weeks. The Sunday after Grande’s murder, Archbishop Romero closed all churches and announced he would instead perform a single Mass, la misa única, in front of the Metropolitan Cathedral in San Salvador. Romero was nervous beforehand, and perhaps afraid, but his words stirred the crowd of one hundred thousand gathered in the streets. The crowd in turn adopted Romero. As one priest present that day put it, “There is baptism by water, and there is baptism by blood. But there is also baptism by the people.”8

Who knows when Romero’s conversion to the poor began, but la misa única made it complete. At almost sixty years old, the safe, establishment-friendly pick of Rome and El Salvador’s elite had become the voice of the brokenhearted and long-despised. “I think that, as Archbishop Romero stood gazing at the mortal remains of Rutilio Grande, the scales fell from his eyes,” Jon Sobrino later said. Bishop Arturo Rivera y Damas, Romero’s onetime rival who became his ally and successor, agreed: “One martyr gave life to another martyr. Before the cadaver of Father Rutilio Grande, Monseñor Romero . . . felt that call of Christ to overcome his natural human timidity and to be filled with the fortitude of the apostle.”9

As for Romero himself, he acknowledged a shift while downplaying the notion of a conversion. “When I went to seminary . . . I started to forget about where I came from. I started creating another world,” he told a friend who asked. “Then they sent me to Santiago de Maria, and I ran into extreme poverty again. Those children were dying just because of the water they were drinking, those campesinos killing themselves in the harvest. . . . When I saw Rutilio dead, I thought, ‘If they killed him for what he was doing, it’s my job to go down that same road.’ . . . So yes, I changed. But I also came back home again.”10 It seems fair to say that something had been stirring in Oscar Romero for some time, and it blossomed in the days surrounding Grande’s death.

The military government was becoming more repressive and the right-wing paramilitary groups more aggressive. In May, Romero was once again called to the site of the assassination of a priest, in what became a sad ritual. One week later, the National Guard attacked the town of Aguilares, occupied it, turned the parish church into a barracks, and refused to allow anyone in, including Romero. When the National Guard finally relented one month later, Romero arrived to find the church destroyed and the Blessed Sacrament desecrated. He conducted Mass and told the poor campesinos, “You are the image of the divine victim ‘pierced for our offenses,’ . . . you are Christ today, suffering in history.”11 Then he led a march through town, right before the watchful eyes of the heavily armed National Guard troops.

Tensions continued to rise throughout the rest of 1977. Angry at the lack of progress investigating Grande’s murder, Romero boycotted the inauguration of the new president, General Carlos Humberto Romero. The government passed the Law for Defense of Public Order, which shredded due process, civil rights, and legal protections under the pretense of maintaining national security. For a decade, popular movements demanding reforms had been on the rise. The government and right wing increasingly turned to violence—murders of priests and mass killings, which had been rare since the 1930s—to reassert control. As such horrors became commonplace, the popular organizations became more radical, and some on the far left responded with violence. A deadly civil war seemed inevitable.

Romero responded to the mounting repression in 1978 and 1979 with the moral authority of his position. He mobilized church resources to assist the poor, especially those who had been victims of violence. He created a Legal Aid Office that compiled accounts of human rights abuses. He opened the doors of seminaries and other church properties to those who had been forced to flee their homes. Making wise use of his immense platform, Romero also became the voice of truth in El Salvador.

The far right controlled many media outlets and intimidated the rest into silence. Killings were hushed up and innocent victims accused of being Communist provocateurs. Some families never knew which military unit or far-right paramilitary organization killed their loved ones. Others had to fight a concocted story excusing the murder. Romero investigated the details and publicly reported the results from the pulpit on Sundays. He spent hours on careful preparation of his sermons, listening to allies and friends among the poor, and then took the pulpit with a handful of notes and spoke from the heart. He also rediscovered the power of his talent for radio communication. His sermons and messages were broadcast throughout the country and became a source of hope for millions.

Romero denounced the injustice of the system and defended the rights of the poor. “In our country the right they are demanding is hardly more than the right to survive, to escape from misery,” he said.12 In his homilies, he insisted, “We cannot segregate God’s word from the historical reality in which it is proclaimed. It would not then be God’s word. . . . It would be a pious book, a Bible that is just a book in our library. It becomes God’s word because it vivifies, enlightens, contrasts, repudiates, praises what is going on today in this society.”13 Above all, he made poverty and violence a moral cause. “Nothing is so important to the church as human life, as the human person, above all, the person of the poor and the oppressed,” he preached. “That bloodshed, those deaths, are beyond all politics. They touch the very heart of God.”14

In June 1977, a far-right paramilitary group gave Jesuits thirty days to leave El Salvador or be killed. In 1979, Father Octavio Ortiz was killed along with four teenagers while at a Catholic retreat center. The police claimed the occupants had fired on them, but Romero had known Ortiz since the latter was a small boy and knew it was impossible. A trickle of individual murders and disappearances turned into a flood. In May 1979, the military fired on peaceful demonstrators in front of the national cathedral, killing and wounding dozens. Foreign journalists caught the gruesome event on tape.

In July 1979, the Sandinista rebels overthrew the Somoza dictatorship in Nicaragua. It was a final warning sign for the Salvadoran military government. A cadre of junior officers mounted a coup against General Romero (no relation) on October 15, 1979, formed a joint civilian-military government, and promised reforms. Romero was hopeful and tepidly welcomed the new junta. His stance angered some allies. By early 1980, though, Romero had lost hope. The unstable government collapsed and re-formed, and tensions soared in the wake of another mass shooting. In March, after a far-right group assassinated one of the leaders of the Christian Democrat Party, the remaining civilian members of the government resigned.

In February, Romero had written a public letter to US president Jimmy Carter, begging the United States to cease its military and financial support of repressive El Salvadoran regimes. He read the letter aloud at Sunday services, broadcast over the radio. The next day the church radio station was bombed.

Romero had always known his life was under threat. He knew it the moment he looked at the body of Rutilio Grande and decided to pick up where his friend left off. But he came to peace with his potential fate. “I must tell you that, as a Christian, I do not believe in death without resurrection,” he said shortly before his death. “If they kill me I will rise again in the Salvadoran people.”15 He recognized death as a possible consequence of letting his soul become entirely possessed by God. In early March, a bomb was found near the altar where Romero was to preach. He told journalists he forgave and blessed whoever might kill him and told friends, “When what I’m expecting to happen, happens, I want to be alone, so it’s only me they get. I don’t want anyone else to suffer.”16

On March 23, 1980, Romero delivered a homily, again broadcast on the radio. Once more, he listed the deaths and disappearances. Once more, he denounced the violence and oppression. This time he pleaded with ordinary soldiers—most Catholics, just like their officers and the oligarchs in power—to defy orders to hurt civilians: “In the name of God, and in the name of this long-suffering people, whose laments rise to heaven every day more tumultuous, I beseech you, I beg you, I command you in the name of God: ‘Stop the repression!’”17

The next afternoon, Romero performed a funeral Mass in the chapel of Divine Providence Hospital, where he had made his residence since becoming archbishop. “One must not love oneself so much as to avoid getting involved in the risks of life that history demands of us,” he told those gathered. “Those who out of love for Christ give themselves to the service of others will live, like the grain of wheat that dies, but only apparently . . . the harvest comes about only because it dies, allowing itself to be sacrificed in the earth and destroyed.”18 Moments later, as he stood before the altar, a shot rang out, and a single bullet pierced Oscar Romero’s heart.

LEGACY AND CRITICISM

Liberation theologian Gustavo Gutiérrez once remarked, “The life and death of Monseñor Romero divides the recent history of the Latin American church into a before and after.”19 What did he mean? Certainly not that Romero’s death ended the violence. Romero’s funeral, in fact, became the site of a bloodbath when army soldiers once again fired on an unarmed crowd. National Guard and army massacres claimed 600 civilians in May and another 800 in December. In 1980, El Salvador tipped over into outright civil war. The army and right-wing death squads turned Romero’s homeland into a killing field. At least 75,000 were killed, 7,000 disappeared, and more than 1,500,000 were displaced from their homes. According to the postconflict UN Truth Commission, right-wing groups were responsible for 95 percent of civilian deaths.20

Despite Romero’s protestations, US military aid continued flowing. One-third of the population fled for safety in the United States, some without proper documentation. Though the civil war ended in 1992, crime remains high. We cannot hope to consider contemporary political flash points—from immigration to the rise of the predominantly Salvadoran MS-13 gang—without understanding the history of Romero’s country.21

Nor does Gutiérrez imply that Romero was the only Christian martyr in El Salvador. In 1980, National Guard soldiers raped and murdered four US nuns. In 1989, Salvadoran army troops shot and killed six Jesuit priests, their housekeeper, and her teenage daughter. Both incidents incited worldwide condemnation. Yet the fact remains that Romero was archbishop and the representative of the Roman Catholic Church in El Salvador. He was the first Catholic bishop murdered in a church since English soldiers struck down the archbishop of Canterbury, Thomas Becket, in 1170.22

Gutiérrez observes that Romero tilted the direction of the church in Latin America decisively in favor of the poor. His martyrdom marked the conversion of the church itself. Romero became an inspiration to many in the church in Latin America and gave them the courage to speak out. Where once the church had been a conservative institution with a growing liberationist element, it became a church of the poor that sought balance with its conservative tradition.

In his own lifetime, Romero faced severe criticism from his fellow Catholics. The landowners and military men responsible for brutal crackdowns were practicing Catholics. There were also fellow clergy who opposed his moves and even offered written dissents to his pastoral letters. El Salvadoran journalist Carlos Dada writes, “Conservative Salvadoran bishops were blessing military tanks, blaming Liberation Theology for the military attacks against the Church, and speaking against Romero to Rome.”23 Rome itself was antagonistic toward Romero and dispatched envoys to investigate him. In 1979, Romero met with Pope John Paul II in Rome. He disappointed Romero by directing the archbishop to seek a better relationship with the government.

Romero grew as an individual throughout his life. As he accepted greater responsibility, he allowed it to change him. He sought spiritual direction and expert psychological help to heal and grow as an individual. He had the soul of a mystic, eventually becoming “possessed entirely by God,” not through silent meditation or fasting but through solidarity with the despised of the earth. He reminds us that, as embodied creatures, our spirituality is also a matter of how we relate to others.

Oscar Romero’s life, like Mother Teresa’s, calls all of us to greater compassion and action on behalf of the global poor. The two represent different models of how to respond to extreme poverty. For all their seeming differences, Mother Teresa and Oscar Romero shared a radical commitment to the poor. Romero was not a theologian, but he was a gifted communicator who left us with a powerful moral vision. Scott Wright says Romero’s spirituality comes down to three themes: “the dignity of the human person, the salvation of people in history, and the transcendent dimension of liberation.”24 According to Jon Sobrino, Romero made Catholic social teaching on the poor specific and concrete, pointing to the landless peasants, the starving laborers, the widows of the disappeared, the children sick and dying. Romero insisted that those poor were not just individuals in need of charity but a multitude that could become agents of their own liberation.25 As he wrote in his fourth pastoral letter:

The church would betray its own love for God and its fidelity to the gospel if it stopped being the “voice for the voiceless,” a defender of the rights of the poor, a promoter of every just aspiration for liberation, a guide, an empowerer, a humanizer of every legitimate struggle to achieve a more just society, a society that prepares the way for the true kingdom of God. This demands of the church a greater presence among the poor. It ought to be in solidarity with them, running the risks they run, enduring the persecution that is their fate, ready to give the greatest possible testimony to its love by defending and promoting those who were first in Jesus’ love.26

Romero challenges both Christians who conflate religion with politics and those who limit Christ’s mission to personal salvation instead of the renewal of all creation. “The church wants to offer no other contribution than that of the gospel,” he insisted, before noting that the gospel is “the full salvation and betterment of men and women, a salvation that also involves the structures within which Salvadorans live, so that, rather than get in their way, the structures can help them live out their lives as children of God.”27

Romero, a man of intense spirituality, crafted a vision of a holistic faith. “Without God, there can be no true concept of liberation.”28 Authentic Christian liberation involves “the whole person,” not just the soul, “demands a conversion of heart and mind, is not satisfied with merely structural changes,” and, of course, “excludes violence.” He continues, “Faith and politics ought to be united in a Christian who has a political vocation, but they are not to be identified. . . . Faith ought to inspire political action but not be mistaken for it.”29

The willingness to critique structures is a source of confusion about Marxism and liberation theology. Catholic conservatives saw Romero giving succor to the popular movements that demanded land reform, nationalization, and wealth redistribution. Many thought him a closet Marxist. They criticized his relationships with leaders of popular organizations and accused him of overstepping his authority and interfering in matters that were not the affair of the church. Though Romero condemned all violence, conservatives accused him of conveniently overlooking leftist violence.

For most of his life Romero had a brittle, prickly personality. He sought perfection in himself and responded harshly to criticism. He started off friendly with the elite and reluctant to offend them. He shied away from confrontation, especially while pursuing his ambitions. In his years as archbishop, however, he welcomed critique and humbly considered its merit, while retaining the willpower to maintain his convictions even when others were not pleased. His personal growth is evidence that his conversion was not just a shift of ideology but a deep spiritual transformation.

What of that conversion, though? Romero was alive for the massacre of peasants in 1932. He lived his whole adult life in El Salvador watching military regimes come and go. He grew up poor and could not claim ignorance of the extreme poverty around him. What took so long? It is not unfair to claim that Romero embraced the cause only when, as he put it, the fight came to the altar. What about those, such as Rutilio Grande, who saw the situation clearly from the start? Should Grande be the subject of this chapter, not Romero? We praised Dietrich Bonhoeffer for seeing injustice early. For consistency’s sake, we should fault Romero for failing to do so.

And yet, some humility is required. All of us have misjudged a situation or taken too long to realize our own complicity. We should honor Romero for the courage to make an abrupt change when it would have been far easier to sink into defensive stubbornness. We are too quick today to dismiss those who are “late to the party.” We question their moral character for taking so long to realize what was obvious to us. Romero reminds us that human beings are constantly growing. His legacy should caution us not to make an idol of consistency but value where people end up.

Oscar Romero remains controversial. Many who opposed him then are still alive today. No one was ever charged or convicted for his death. Reasonable suspicion points to two men. Roberto D’Aubuisson likely gave the order. He was a former major in the Salvadoran army and leader of a paramilitary terrorist organization credited with the rise of death squads during the civil war. He went on to become a popular far-right political figure before dying in the early 1990s. Captain Álvaro Rafael Savaria likely pulled the trigger. He fled to the United States. He was later briefly arrested and held for extradition before a right-wing Salvadoran government dropped the request.

Many of the people who funded, supported, and protected Romero’s killers remain powerful and wealthy. For these people, Romero is still what he always was: a misguided priest who forgot his place and got what was coming to him. To the poor of El Salvador, however, he remains a beloved figure. Soon after his death, long before there was any momentum for his canonization within the Catholic Church, the people were already calling him “Saint Romero.”

His reception within the Catholic Church today mirrors the tensions in his own time. No one wants to appear to oppose a martyr of the church. Yet many still insist that he abandoned the gospel of Jesus Christ and adopted a heretical theology that baptizes class warfare. Many prominent Catholics in El Salvador, who give generously to the church, were political opponents of Romero. Unfortunately, some Romero supporters have sought to make him more palatable by presenting him as a martyr for his Christian faith, not the cause of the impoverished. Remembering Romero this way distorts his legacy and tears apart two things—following God and siding with the poor—that he believed to be inseparable. As Romero once noted, “Not any and every priest has been persecuted, not any and every institution has been attacked. That part of the church has been attacked and persecuted that put itself on the side of the people and went to the people’s defense.”30

Debate continues over whether Pope John Paul II supported Romero during his life and, later, the cause of his canonization. Despite their icy meeting, Pope John Paul II demanded to pray at Romero’s tomb in the San Salvador cathedral during a visit to El Salvador. The evidence seems clear, however, that Pope John Paul II was in no hurry to canonize someone whose theology he had condemned, and the Salvadoran government lobbied against honoring Romero. After John Paul II’s death, the cause of Romero’s canonization became “unblocked.”31

Romero was beatified in 2015 by Pope Francis, himself an Argentinian cardinal before becoming pope. “We say of that world of the poor that it is the key to understanding the Christian faith, to understanding the activity of the Church and the political dimensions of the faith,” Romero said shortly before his death. “It is the poor who tell us what the world is, and what the Church’s service to the world should be.”32 Oscar Romero’s legacy lives on in Pope Francis’s call for the Catholic Church to become “a poor church, for the poor.”33

LEADERSHIP LESSONS

Oscar Romero’s life and work offer a number of important lessons about moral leadership:

- It is never too late. You may have spent an entire career in one line of work or a lifetime with certain beliefs, but it is never too late to change. What you do tomorrow better defines you as a leader than what you did yesterday.

- Practice self-examination. Romero dared to look at himself in the mirror and to grow as an individual over the course of his life. Never let the pursuit of perfection be such a high ideal that it is unattainable, but never cease trying to improve and become a better version of yourself.

- Evaluate structures. Seeing the whole forest—not just the trees—is a hard skill to learn but an important one to master. Study the structures of human communities, how systems interconnect, who benefits, and who suffers. It will help you better work with individuals within those systems and create change at a far larger scale.

- Develop communication and listening skills. Romero had a talent for communicating over the radio all his life. Understanding technology, especially communications technology, helps leaders reach people in new ways. Where Romero changed was in realizing that the best communicators spend more time listening than they do speaking.

- Responsibility changes you. As archbishop, in the capital city, Romero had a responsibility to look after his flock and to protect the church and its clergy—and he changed from the man he was. Do not assume that you will remain the same person once you have responsibility to protect and care for others. It changes all of us.

Oscar Romero stands at the forefront of a theology in which Christians are called to participate in a kingdom of God that is beyond our control or comprehension. Such a theology belies easy categorization. It refuses to idolize wealth or power, or to sacrifice human beings in the name of national security or social order. Yet it does not shy away from the brutalities of the human heart:

How easy it is to denounce structural injustice, institutionalized violence, social sin! And it is true, this sin is everywhere, but where are the roots of this social sin? In the heart of every human being. Present-day society is a sort of anonymous world in which no one is willing to admit guilt, and everyone is responsible. We are all sinners, and we have all contributed to this massive crime and violence in our country. Salvation begins with the human person, with human dignity, with saving every person from sin.34

Romero did not just minister to the poor; he also tried to evangelize the society that made them poor. Perhaps that is his legacy—testifying to the repercussions of bringing God’s justice into a fallen world:

It is very easy to be servants of the word without disturbing the world: a very spiritualized word, a word without any commitment to history, a word that can sound in any part of the world because it belongs to no part of the world. A word like that creates no problems, starts no problems. What starts conflicts and persecutions, what marks the genuine church, is the word that, burning like the prophets, proclaims and accuses . . . this is the hard service of the word. But God’s Spirit goes with the prophet, with the preacher, for he is Christ, who keeps on proclaiming his reign to the people of all times.35

DISCUSSION QUESTIONS

- What do you think of Oscar Romero’s conversion? What caused it?

- Compare Mother Teresa’s and Oscar Romero’s approaches to poverty. Which do you find most compelling? Why?

- How did Romero’s spirituality affect his sense of vocation?

- What do you make of Romero’s childhood and the effect it had on his later conversion?

- What was the relationship between Romero and John Paul II? How does it change your opinion of each man?

FOR FURTHER READING

Brockman, James R. Romero: A Life; The Essential Biography of a Modern Martyr and Christian Hero. Maryknoll, NY: Orbis, 2005.

Romero, Oscar. The Church Cannot Remain Silent: Unpublished Letters and Other Writings. Translated by Gene Palumbo and Dinah Livingstone. Maryknoll, NY: Orbis, 2016.

———. Voice of the Voiceless: The Four Pastoral Letters and Other Statements. Translated by Michael J. Walsh. Maryknoll, NY: Orbis, 1985.

Wright, Scott. Oscar Romero and the Communion of the Saints. Maryknoll, NY: Orbis, 2009.

Zynda, Damian. Archbishop Oscar Romero: A Disciple Who Revealed the Glory of God. Scranton, PA: University of Scranton Press, 2010.

1. James R. Brockman, Romero: A Life; The Essential Biography of a Modern Martyr and Christian Hero (Maryknoll, NY: Orbis, 2005), 214.

2. Scott Wright, Oscar Romero and the Communion of the Saints (Maryknoll, NY: Orbis, 2009), 24.

3. Wright, Oscar Romero, 41.

4. Wright, Oscar Romero, 14.

5. Wright, Oscar Romero, 9.

6. Damian Zynda, Archbishop Oscar Romero: A Disciple Who Revealed the Glory of God (Scranton, PA: University of Scranton Press, 2010), 1.

7. Damian Zynda, “Archbishop Oscar Romero: A Life Witness to the Glory of God,” in Archbishop Romero and Spiritual Leadership in the Modern World, ed. Robert S. Pelton (Lanham, MD: Lexington, 2015), 47.

8. Wright, Oscar Romero, 49.

9. Wright, Oscar Romero, 50.

10. Wright, Oscar Romero, 53.

11. Wright, Oscar Romero, 59.

12. Wright, Oscar Romero, 78.

13. Wright, Oscar Romero, 68.

14. Wright, Oscar Romero, 126.

15. Wright, Oscar Romero, 137.

16. Wright, Oscar Romero, 126.

17. Wright, Oscar Romero, 130.

18. Oscar Romero, “Last Homily of Archbishop Romero,” in Voice of the Voiceless: The Four Pastoral Letters and Other Statements, trans. Michael J. Walsh (Maryknoll, NY: Orbis, 1985), 191–92.

19. Wright, Oscar Romero, 136.

20. Wright, Oscar Romero, 4.

21. Wright, Oscar Romero, 5.

22. Carlos Dada, “The Beatification of Oscar Romero,” New Yorker, May 19, 2015, https://www.newyorker.com/news/news-desk/the-beatification-of-oscar-romero.

23. Dada, “Beatification of Oscar Romero.”

24. Wright, Oscar Romero, 129.

25. Jon Sobrino, “A Theologian’s View of Oscar Romero,” in Voice of the Voiceless, 40–41.

26. Romero, “Fourth Pastoral Letter,” in Voice of the Voiceless, 138.

27. Romero, “Fourth Pastoral Letter,” in Voice of the Voiceless, 128.

28. Wright, Oscar Romero, 129.

29. Romero, “Third Pastoral Letter,” in Voice of the Voiceless, 99–100.

30. Wright, Oscar Romero, 133.

31. Dada, “Beatification of Oscar Romero.”

32. Romero, “Political Dimensions of the Faith,” in Voice of the Voiceless, 179.

33. “Pope Francis Wants ‘Poor Church for the Poor,’” BBC News, March 16, 2013, http://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-21812545.

34. Wright, Oscar Romero, 128.

35. Wright, Oscar Romero, 90.