fourteen

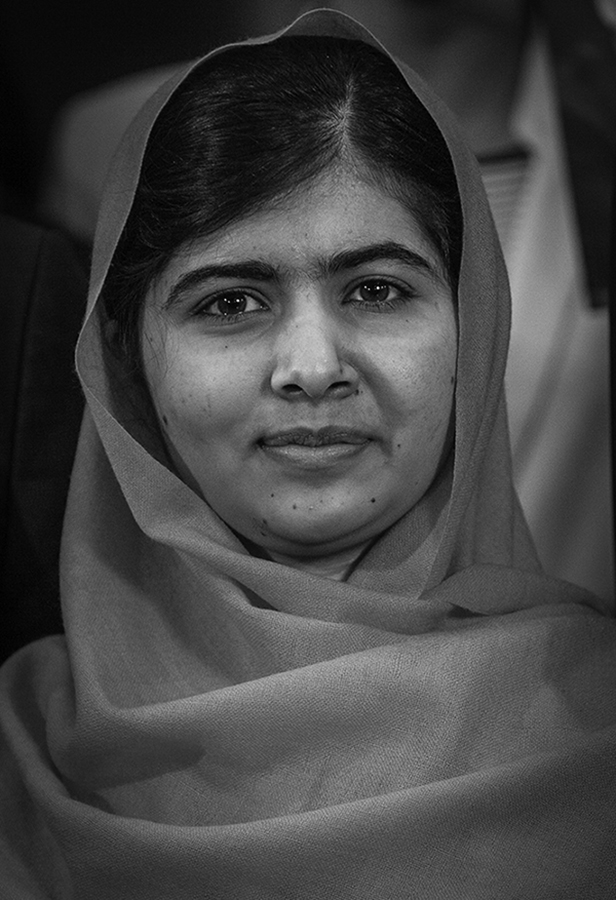

Malala Yousafzai

1997–

1997 (July 12): Born in Mingora, in the Swat district of Pakistan.

1999: Brother Khushal born.

2001 (Sept. 11): Attacks on US World Trade Center and Pentagon; war in Afghanistan begins soon after.

2002: Brother Atal born.

2005 (Oct.): Massive earthquake strikes Pakistan.

2007 (July): Militants seize the Red Mosque in Islamabad.

2007 (Sept.): Taliban gains effective control over the Swat Valley.

2007 (Oct.): Dozens die in terrorist attack on parade in honor of former prime minister Benazir Bhutto, who had just returned from exile.

2007 (Oct.–Nov.): First Pakistani Army invasion of Swat Valley.

2007 (Dec. 27): Benazir Bhutto assassinated.

2008: Taliban destroys hundreds of girls’ schools in Pakistan.

2008 (Sept. 1): Gives first public speech.

2008 (Dec.): Taliban bans girls from attending school in Swat; later amends edict to allow education if properly dressed.

2009 (Jan. 3): Writes first blog post for BBC Urdu under pseudonym “Gul Makai.”

2009 (Feb. 16): Taliban and Pakistani government strike peace deal, allowing Islamic law in Swat.

2009 (Feb. 22): Permanent ceasefire announced; lasts until May.

2009 (Mar.): Stops blogging. Subject of short New York Times documentary.

2009 (May 1): Second Pakistani Army invasion of Swat Valley; becomes IDP (internally displaced person) along with entire family.

2009 (July 24): Returns to Swat Valley; on journey back, asks American diplomat Richard Holbrooke for help with girls’ education.

2009 (Aug. 1): Returns to school.

2009 (Dec.): Becomes widely known as the person behind “Gul Makai” blog posts.

2010–11: Balances school with campaigning for education. Taliban commits targeted attacks and assassinations throughout Pakistan.

2010 (July): Torrential rainfall causes mass flooding affecting more than 14 million in Pakistan.

2011 (May 2): American forces kill Osama bin Laden in Abbottabad, Pakistan.

2011: Awarded Pakistan’s first National Peace Award for Youth (Dec. 20). Archbishop Desmond Tutu nominates Malala for KidsRights Foundation International Children’s Peace Prize.

2012 (Jan.): School in Karachi named in Malala’s honor. Taliban issues public threat against Malala’s life.

2012 (Aug. 3): Family friend Zahid Kahn shot by Taliban.

2012 (Oct. 9): Shot in the head as she rides home from school; two classmates also wounded.

2012 (Oct. 12): International outrage over Malala’s shooting grows; Pakistani government offers reward for information.

2012 (Oct. 15): Airlifted to England to continue treatment. UN Special Envoy for Global Education launches “I Am Malala” online petition.

2012 (Oct. 16): Awakens in Birmingham, England.

2012 (Dec. 31): Named runner-up for Time Person of the Year.

2013 (Feb. 3): Undergoes final surgery before release.

2013 (Feb. 8): Released from Queen Elizabeth Hospital.

2013 (Mar. 19): Returns to high school.

2013 (July 12): Addresses the United Nations General Assembly on right to universal education; UN declares July 12, her birthday, “Malala Day.”

2013 (Sept. 6): Wins the International Children’s Peace Prize.

2013: Meets US president Barack Obama and the Queen of England.

2013 (Oct.): Establishes the Malala Fund.

2013 (Oct. 8): Publishes autobiography I Am Malala. Taliban renews threat against her life.

2013 (Nov. 20): Awarded Sakharov Prize.

2013 (Dec. 10): Awarded United Nations Human Rights Prize, award given out only once every five years.

2014: Wins World Children’s Prize; donates $50,000 to schools in Gaza.

2014 (July 12): Visits Nigeria to speak to victims and condemn Boko Haram for misusing Islam.

2014 (Sept. 12): Ten men arrested for participation in attempt to assassinate Malala.

2014 (Oct. 10): Becomes youngest-ever recipient of the Nobel Peace Prize.

2014 (Oct. 21): Becomes honorary Canadian citizen after unanimous House of Commons vote.

2014 (Dec.): Taliban kills around 150 people, mostly children, in attack on school in Peshawar, Pakistan.

2015 (July 12): Celebrates 18th birthday with opening of school in Lebanon.

2015: Documentary He Named Me Malala released internationally; wins Grammy Award for Best Children’s Album for recorded version of her book.

2015 (June 5): Two people sentenced to life in prison for attempt to murder Malala; eight others acquitted.

2016 (July 12): Marks her 19th birthday with refugee girls in Kenya and Rwanda.

2016 (Sept. 7): Launches #YesAllGirls campaign in support of universal education for girls.

2017 (Apr.–Sept.): “Girl Power Trip,” a public awareness–raising mission to Africa, the Middle East, Latin America, and North America.

2017 (Apr. 10): Becomes a UN Messenger of Peace.

2017 (Aug. 17): Announces acceptance to Oxford University, where she remains a student at the time of publication.

2018 (Mar. 29): Visits Pakistan for the first time since being shot.

Malala Yousafzai did not become an advocate for girls’ education because the Taliban tried to murder her for going to school. The Taliban tried to murder Malala because she was already a famous advocate for girls’ education. At a time when many grown adults hid in fear, she stood up to the militants ruining her beloved Pakistan. The Taliban was bombing schools for girls and assassinating well-protected government leaders, and yet she willingly became the public face of a campaign to ensure girls could go to school. Radical fundamentalists, trying to limit women to the home, found themselves confronted in the public square by a teenage girl.

The attack failed to silence her. Nor did it change her focus. Instead, it stiffened her resolve—and made her an instant international celebrity, with far more influence than before. Those who took a moment to study her life encountered a profoundly inspirational young woman of vision and convictions with a mission for her life. Addressing the United Nations, mere months after the shooting, Malala described how her life had changed:

On the 9th of October 2012, the Taliban shot me on the left side of my forehead. They shot my friends too. They thought that the bullets would silence us. But they failed. And then, out of that silence came thousands of voices. The terrorists thought that they would change our aims and stop our ambitions but nothing changed in my life except this: Weakness, fear and hopelessness died. Strength, power and courage was born. I am the same Malala. My ambitions are the same. My hopes are the same. My dreams are the same.1

You may be wondering how one as young as Malala Yousafzai could be standing alongside some of the biggest names and brightest lights of modern history. By the time you finish this chapter, we trust you will wonder no longer. Malala’s story forces us to ponder some of the most pernicious problems of our time: oppression of girls and women, limits on access to education, religious fundamentalism, the plight of refugees, and international terrorism. Our guide through these thorny topics is a young woman who has demonstrated unmistakable grace and poise and earned the mantle of moral leadership. As you read on, we believe you will find inspiration in the story of a young woman from a poor town in Pakistan who dared to speak up for girls everywhere.

HISTORICAL CONTEXT

Pakistan was born at midnight on August 14, 1947. Under British rule, the nations we know today as Pakistan, Bangladesh, and India were all one territory. The territorial divide at the end of British control only left more conflict in its wake. India and Pakistan fought wars in 1947, 1965, and 1971, the last of which would transform what was then East Pakistan into the nation of Bangladesh. The relationship between India and Pakistan remains tense, especially over the contested region of Kashmir, and the bitterness between the two nuclear powers leaves many experts nervous about ramifications of future conflict.

Though a young nation on paper, Pakistan boasts regions home to ancient and proud civilizations. The Swat Valley, where Malala grew up, was once filled with ancient Buddhist temples. Islam came to the area in the eleventh century. It is also an ethnically and linguistically diverse land. Malala’s last name, Yousafzai, is also the name of her tribe, one of the largest of the Pashtun people, who span across Afghanistan and Pakistan. The Swat Valley joined Pakistan in 1947 but remained, for the first few years, an autonomous region under local rule. Malala says she and her neighbors considered themselves “first as Swati and then Pashtun, before Pakistani.”2

The region has a turbulent recent history. Malala is named after Malalai, the Pashtun “Joan of Arc” who died as a martyr in 1880 leading her people against British occupation. She was a poor shepherd girl who went out to tend to the wounded and, seeing her people in retreat, hoisted a flag and inspired her people to follow her into battle before dying in the fighting. Assassinations and military coups marred the first decades of Pakistan’s independence. In 1971, General Zia ul-Haq seized power in a military coup. He was an international pariah until the USSR invaded Afghanistan in 1979. Suddenly, Western powers saw General Zia as a bulwark against the Soviets.

After Zia died in a plane crash in 1988, Benazir Bhutto became the first female prime minister in the Islamic world. She and a man named Nawaz Sharif would trade control, amid allegations of corruption and army intervention, for years to come. In 1999, General Pervez Musharraf seized power, and once again the international community rained condemnations until they needed his assistance to fight the terrorist group Al-Qaeda and the fundamentalist Islamic government of Afghanistan, the Taliban.

The Taliban would not exist without Western intervention. During the decade-long fight against the Soviets in Afghanistan, the Pakistan intelligence agency (ISI) and the American Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) funded and supported the mujahideen, “freedom fighters,” who preceded the Taliban and Al-Qaeda. Many of these were Pashtun like Malala, while countless other Pashtuns spilled over the border and settled as refugees in the Swat Valley. To resist the Soviets, General Zia promoted the idea of armed jihad, and fundamentalist Muslim teachers rose to prominence encouraging the young men of Swat to go fight in the name of Islam. Volunteers from across the Islamic world came to join them, including a charismatic young Saudi billionaire named Osama bin Laden.

Islam grew out of the teachings of the Prophet Muhammad in the early 600s, and it swept across the Middle East, Africa, and southeastern Europe over the following century. After the Prophet’s death in 622, an internal struggle ensued over whether leadership would fall to his close allies or his family. That conflict began the split between Shia (or Shiite) and Sunni Muslims, the two largest groups within Islam today. Most of Pakistan is Sunni, as are the Yousafzais. Among Sunnis in Pakistan there are dozens of distinct groups. Islam has always included as many conflicting and diverse interpretations, theologies, and practices as any major religion—mystics and legalists, traditionalists and modernists, liberals and conservatives.

The Taliban, who seized power in Afghanistan in 1996 after the withdrawal of the Russians in 1988 and who famously sheltered Al-Qaeda, represent a fundamentalist, extremist strain within Islam. Most of the people where Malala grew up were conservative Muslims and yet deplored the Taliban and their version of Islam. It might help to imagine a conservative county in the southern United States, one where most people attend church regularly, falling under the thumb of medieval-style Crusaders determined to kill infidels in the name of Christ.

In her autobiography, Malala disapprovingly cites General Zia’s attempt to curtail women’s rights, rewrite history books to disparage other religions, and launch campaigns of religious education. What Zia and other leaders failed to do was bring widespread economic opportunity. Facing poverty and few chances to get ahead in life, people felt the conflicting appeals of secularism and socialism on the one hand and militant Islam on the other. Pakistan today struggles with high rates of poverty like other former colonies. More than a third of the country lives below the poverty line. There is also a growing gap between urban wealth and rural poverty.

Poverty and lack of education are two sides of the same coin. The global poor routinely face obstacles to education, which makes it harder to escape economic systems rigged against them. Women and girls bear the brunt of both. They are more likely to be uneducated and more likely to live in poverty. Sexism is perhaps the world’s oldest prejudice, and it manifests itself everywhere. It simply becomes most noticeable in societies where men impose cruel restrictions, including denying women an education.

The Malala Fund estimates that more than 130 million girls around the world do not have access to an education, while more conservative estimates place the number around 66 million. The reasons span from parents who do not believe girls should be educated, to child labor, forced marriage, prohibitive costs, violent conflicts, refugee crises, and a simple lack of schools. Malala could easily have been one of those girls, or merely offered prayers of thanks that she was not. Instead, she made it her cause to speak up on their behalf. “I am not a lone voice. I am many,” she insisted in her Nobel Prize acceptance speech. “I am those 66 million girls who are deprived of education. And today I am not raising my voice, it is the voice of those 66 million girls.”3

EARLY AND PRIVATE LIFE

The first child of Ziauddin and Toor Pekai Yousafzai, Malala Yousafzai was born on July 12, 1997. Her parents lost a child, stillborn, in 1995. The arrival of a girl brought condolences from some neighbors, but her father, Ziauddin, was overjoyed and broke sexist precedent by adding Malala to the family registry. It was not the last time Ziauddin would open doors to Malala that other fathers might have slammed shut. Mingora, where she was born, was the largest town in the Swat Valley but small compared to major cities. The Swat Valley itself was a place of stunning natural beauty—the “Switzerland” of Pakistan, with towering mountains and lush greenery beneath deep blue skies—that was once a major tourist destination.

“We knew what it was like to be hungry,” Malala recalls of her youth, citing it as motivation for her family’s charity efforts.4 The family was more secure as Malala grew older and her father’s school became more successful. By the time she was a young teen, they had a television and money for books and DVDs. Malala loved the Twilight series and American shows such as Ugly Betty. Two years after she was born, a brother, Khushal, arrived, and her youngest brother, Atal, joined three years after Khushal. Girls from school play a bigger role in Malala’s stories of her childhood than do her brothers, but she seems to have had as typical of a sibling relationship as was possible under the circumstances. Lots of sisters fight with their brothers, but few admit to doing so in a speech accepting the Nobel Peace Prize.

Two events in Malala’s young life seem to have had a profound effect. First, she recalls passing an area where people dumped their trash and spying small children crawling over the rubbish pile. It devastated her, and she talked to her father about why no one would help such children. Memory of the incident constantly reminded her that there were others in greater need, no matter how difficult her life. Second, she recounts a period in her childhood when she started stealing from a friend and lying about it to her parents. Her parents caught on quickly and waited for her to confess. Even though she was only seven at the time, she tells the story with great shame, claiming, “Since that day, I have never lied or stolen. . . . I also stopped wearing jewelry, because I asked, ‘What are these baubles which tempt me? Why should I lose my character for a few metal trinkets?’”5

Those significant events are nothing next to the influence of her parents. Malala’s mother and father had a “love marriage,” not an arranged one. They came from neighboring villages, and Ziauddin courted Toor Pekai even though their powerful grandfathers did not get along.

Toor Pekai is a pious woman from a family of strong women, though in many ways she embraces the same gender roles that her husband encouraged their daughter to challenge. She spent most of the time with her young children while Ziauddin pursued a career and got involved in various causes. She could neither read nor speak English until recent years. Nor did she, until recently, speak publicly about Malala. Malala would later say her mother inspired her to “be patient and to always speak the truth—which we strongly believe is the true message of Islam.”6 Despite never going to school, she wanted her daughter to study and gave her the courage to continue. She was also a counselor to Ziauddin in his career and political campaigning.

Nevertheless, Malala’s father, Ziauddin, was the more significant influence on her life. As a young man growing up in the Swat Valley, he felt the pull of the jihadis who promised glory when his only other option appeared to be a life in the mines. But the secular nationalism of Toor Pekai’s brother also appealed to him, and Malala claims he ended up somewhere in the middle. Despite a stammer at a young age, Ziauddin won a college speech competition with a thundering attack on those who believed Islam so weak that banning books was necessary. His father wanted him to become a doctor, but he dreamed of starting a school in the Swat Valley. And despite fallouts with business partners, money troubles, and even flooding, he pursued that dream successfully.

Ziauddin was committed from the start to teaching girls and passed down his love of education to his daughter. Malala was the light of Ziauddin’s life. In a foreboding move, he named her after a woman who inspired her people—but fell in battle. Some in the family objected because the name “Malala” means “grief-stricken,” but Ziauddin insisted. Ziauddin’s passion for education became Malala’s passion. So, too, did his political activism, both before and after the Taliban arrived in the Swat Valley. From him, she learned public speaking and how to write her own remarks. In her Nobel Prize acceptance speech, Malala thanked her father “for not clipping my wings and for letting me fly.”7 When asked what her life would be like if she were an ordinary girl, Malala replied, “I am an ordinary girl. But if I had an ordinary mother and father, I would have two children now.”8

It seems redundant to say that the family placed a premium on education. Malala was always first or second in her class. Watch her speak and you will see an agile and thoughtful mind at work. She learned English as well as math, science, history, and more. Later, she would talk about reading Stephen Hawking’s A Brief History of Time—no easy book—as a mental escape from life under the Taliban. Later, she would admit to struggling with the adjustment to tougher standards at her school in Britain. In 2017, she began collegiate studies at Oxford.

The Yousafzais are a devout Muslim family. In her autobiography, Malala talks about keeping the five pillars of Islam: faith, prayer, charity, fasting, and the pilgrimage to Mecca. She recounts that the British nurses who cared for her after she was shot did not realize quite how conservative she is. They bought her clothing she would never wear, and Malala had to ask them to turn off a movie, Bend It Like Beckham, the story of a young girl throwing off cultural constraints, after a scene she found too risqué.

The Taliban accuses Malala of joining forces with secularism to oppose Islam, but the truth could not be more different. She makes it clear, in fact, that her faith drove her to speak up. “We could not just stand by and see those injustices of the terrorists denying our rights, ruthlessly killing people and misusing the name of Islam,” she said in her Nobel Prize speech. “We decided to raise our voice and tell them: Have you not learned that in the Holy Quran Allah says: if you kill one person it is as if you kill the whole humanity?”9

At the United Nations, Malala criticized Talib who “think that God is a tiny, little conservative being who would send girls to the hell just because of going to school.” Terrorists are “misusing the name of Islam and Pashtun society for their own personal benefits,” she declared, and they do not realize that “Islam says that it is not only each child’s right to get education, rather it is their duty and responsibility.”10 She criticizes the Taliban not as an outsider but as a Muslim offended at the distortion of her faith by a radical sect.

Hardship, poverty, conflict, lack of education, and turbulent change create room for the message of evil people to grow. That is exactly what happened in Malala’s beloved Swat Valley. Her autobiography drips with sadness for the idyllic life of her childhood. They might not have had much, but the Swat Valley was a beautiful place to live. Malala attended school with the same group of girls for years, and they became close confidants and friendly rivals. Once a year her parents would take the kids to visit the family village high up in the valley. Millions of people read about Malala’s childhood and see similarities with their own. That all changed, though, when the Taliban came to Swat.

VOCATION

Maulana Sufi Fazlullah had the most popular radio talk show in the Swat Valley—so popular, in fact, that it earned him the nickname “the Radio Mullah.” At first, he gained listeners with a popular, folksy style, interpreting the news of the day through a hard-line Islamic lens. In turbulent times, people tend to gravitate to those, like Fazlullah, who speak with certainty and paint the world in black-and-white terms. Fazlullah was the leader of the Swat Valley Taliban, and he used his radio show to gain a following and to incite violence against those who opposed him.

Malala says the Swat Valley had always been more conservative than the rest of the country, and some young men went to fight alongside the Taliban after the United States invaded in 2001. Hard-line Islamic groups also won affection by providing aid in Swat after a devastating 2005 earthquake. Many locals were upset when American drone strikes aimed at terrorist leaders claimed civilian lives. In addition, men who received little respect in Pakistani society thought they could find glory by joining the militants. Most people could not read Arabic, the language of the Qur’an, and were easy prey for radicals who lied about or misinterpreted its teachings.

These events all made for ripe territory for Fazlullah. He presented himself as a great Islamic scholar, even though, as Ziauddin kept pointing out, he was a high-school dropout. He also won support by holding tribunals to judge cases that might have taken years in the slow, corrupt Pakistani system. He encouraged a hard-line obedience to one radical interpretation of Islamic law and would praise, by name, local people who followed his advice or helped his cause. He used his radio show to encourage charitable works and build a public following. And what the Taliban could not do with propaganda, they did with violence: people were flogged, attacked in the streets, and killed, or they simply disappeared.

The local authorities either joined the Taliban or stayed out of the way. By mid-2007, Fazlullah and the Taliban had effective control over the valley. In 2007, the Pakistani Army made a first attempt to push them out, but militants returned as soon as the army retreated. Life under Taliban control was harsh and terrifying. Malala recalls men and women being murdered and their bodies left in the public square of Mingora. Western movies and DVDs were banned, and offending materials were routinely burned in giant bonfires. Assassinations and bombings targeted government officials or political opponents.

Many who never liked the Taliban, or later came to hate them, were nevertheless scared into silence. Ziauddin was one of those who resisted the Taliban, but he had to do so cautiously for fear of reprisal. One of his priorities was protecting his school from interference by local Taliban-friendly mullahs. He eventually became one of the spokesmen of an informal local group opposing the Taliban. It made him a direct target, and he took to sleeping away from home to keep his family safe.

Women faced some of the cruelest measures. The Taliban demanded that women always have a male relative as an escort when in public and that they dress conservatively in a full burqa (a veil that covered their entire head and concealed their face and eyes). Malala and her family instead wear a hijab, a loose scarf that covers the head and hair but not the face. Women who did not dress according to the conservative standards of the Taliban were attacked on the streets. The Taliban especially hated the idea of educating girls. In 2008, they bombed around four hundred girls’ schools, including a prominent college for women. In December 2008, they issued an edict closing all schools for girls starting in January 2009 but later permitted girls to go to school so long as they wore a full burqa.

It was this attack on women that spurred Malala to follow her father into resistance. She had been horrified in December 2007 when militants assassinated one of her role models, former prime minister Benazir Bhutto. “When we learned she was dead,” Malala writes, “my heart said to me, ‘Why don’t you go there and fight for women’s rights?’”11 No one felt safe after Bhutto’s death, but the repeated school bombings left Malala more convinced than ever of the need to speak out.

In September 2008, she gave her first public speech, in Peshawar, titled, “How Dare the Taliban Take Away My Basic Right to Education?” In January 2009, BBC Urdu invited her to write a blog about her experiences under the pseudonym “Gul Mukai.” For months, her blog painted a powerful portrait of a life in which ordinary school days mixed with horrific violence and fear. She stopped writing in March, but her public appearances caught the attention of journalists, including from the New York Times, which produced a documentary about her.

In May 2009, the Pakistani Army invaded Swat once more. The fighting lasted months, during which Malala and her family fled. The Yousafzais, along with countless others, became internally displaced persons, or IDPs, a category of refugees growing in large numbers across the world. Luckily, they were able to return, and by July the family was back in Swat, only to find her father’s school ransacked. Once again, they rebuilt. The Taliban never regained the public legitimacy they had previously, but they never went away. The army insisted that there were no more Taliban in Swat. Locals disagreed; they had just gone underground. The next few years brought continued bombings and killings, but the violence now seemed carefully targeted.

Malala returned to school but was never again a normal student. She continued speaking to the press and pushing for the right to education whenever she could. Her campaign for girls won the attention of Archbishop Desmond Tutu, who nominated her for the International Children’s Peace Prize of KidsRights. “I know the importance of education because my pens and books were taken from me by force,” she told an audience at the KidsRights gala. “But the girls of Swat are not afraid of anyone. We have continued with our education.”12 In 2011, the prime minister of Pakistan awarded her with the nation’s first-ever National Youth Peace Prize. (She accepted with a long list of demands, including rebuilt schools and a university for girls in Swat.) Malala decided that she would use the prize to start a foundation and convene her first conference, prioritizing street children and kids trapped in child labor.

The attention made her a target. In January 2012, the Taliban issued a public threat against Malala’s life. Friends and family had long warned that Ziauddin was a target, but all except Malala’s mother thought that even the Taliban would not harm a girl. Malala would check around the house obsessively before going to sleep at night and brainstorm how she might respond if someone came to kill her or throw acid on her. She would throw a shoe, she thought, before deciding that doing so would make her too similar to the Taliban. Instead, she believed that if she could talk to her assailant she could change his mind. In her years of campaigning, Malala showed that bravery and fear can live inside the same person.

After the public threat, Malala stood firm. Her father told her that maybe they should quit campaigning until things cooled down. “How can we do that?” she replied. “You were the one who said if we believe in something greater than our lives, then our voices will only multiply even if we are dead. We can’t disown our campaign!”13 She refused to go away to boarding school. She found refuge in prayer. “The Taliban think we are not Muslims but we are,” she reflected. “We believe in God more than they do and we trust him to protect us.”14 She took the precautions that she could. Her mother insisted she ride a rickshaw to and from school instead of walking.

Malala knew the stakes. “I had two options,” she later said. “One was to remain silent and wait to be killed. And the second was to speak up and then be killed. I chose the second one. I decided to speak up.”15

On October 9, 2012, Malala Yousafzai was in the van going home from school—sitting on a bench with her classmates in the open back—when two men stepped out in the road and stopped it. One asked, “Who is Malala?” before firing. She must have ducked, because the bullet struck her above the left eye, exited below her ear, and embedded in her shoulder. Malala didn’t even hear them ask her name, “or I would have explained to them why they should let us girls go to school as well as their own sisters and daughters.”16 Two other girls were wounded as well, though neither as seriously as Malala.

The next hours and days were a blur. The driver sped to the local hospital. The army took over and airlifted her to Peshawar. A CT scan there revealed the injury to be far more severe than first thought. Bits of splintered bone had penetrated her brain, sending her into shock. The talented military surgeon made a gutsy call: to operate, removing part of her skull and giving space for the brain to swell and heal. It saved her life, but no one knew that yet. She developed an infection, and for a time all the family could do was wait and pray. A specialist in pediatric intensive care from the Children’s Hospital of Birmingham, Dr. Fiona Reynolds, was in Pakistan. She agreed to consult when she heard Malala’s story. She said that Malala might not recover without better aftercare, and eventually it was agreed that Malala would be airlifted to Birmingham, England.

“If she’d died,” Dr. Reynolds said afterward, “I would have killed Pakistan’s Mother Teresa.”17 Malala was moved to another hospital within Pakistan, again under army control—with snipers on the roof and streets closed. Then, with the help of the ruling family of the United Arab Emirates, who loaned their private jet, the doctors transported her to England on October 15. Because the Taliban still wants her dead, she did not attempt to return home until March 2018, when she made a brief visit.

Malala woke up in Birmingham one week after the shooting, wondering where her family was. They had trouble with passports and politics until her mother threatened a hunger strike, and they arrived ten days later. It was now clear that Malala would live, but it was some time, and more operations, before it was clear that she would recover cognitively or be able to smile and speak clearly.

Nothing could have prepared Malala for the next few years of her life. The horror of her attempted murder made international headlines. Gordon Brown, the former prime minister of the United Kingdom and then UN Special Envoy for Global Education, launched an “I Am Malala” online petition that quickly surpassed one million signatures. Global leaders shared their condolences, including the children of Benazir Bhutto, who sent Malala two of their mother’s shawls. Malala’s miraculous survival added to her celebrity. So, too, did her insistence that she bore no ill will and wanted no revenge. Her only regret was that the men who shot her never got to hear what she had to say. “I do not even hate the Talib who shot me,” she later said. “Even if there is a gun in my hand and he stands in front of me. I would not shoot him.”18

After Malala was reunited with her parents and brothers, the family settled in Birmingham, England. Her father became a diplomatic attaché for Pakistan and an adviser to the United Nations. Her mother started studying English. Malala went back to school. None of it was easy for people so far from home and unable to return without risking death, but there was a semblance of normality to it. At the same time, there is nothing ordinary about a girl of sixteen addressing the United Nations—or, on October 10, 2014, becoming the youngest-ever recipient of the Nobel Peace Prize, an award she shared with Indian children’s advocate Kailash Satyarthi.

In October 2013, Malala created the Malala Fund, which advocates for girls’ education around the world, funded by the prize money from various awards. She has traveled the world—funding and opening schools, meeting with elected officials, and using her star power to advocate for girls’ education. In Nigeria, she condemned Boko Haram militants for misusing the name of Islam. In the United States, she told President Barak Obama to stop CIA drone bombings and oppose terrorism through education instead of war. Her autobiography and a documentary about her life put a global spotlight on the barriers keeping girls out of schools. In country after country, she met with both leaders of nations and fellow girls, just like her, who want to study and learn and pursue their dreams. Everywhere she goes, she shares the same message:

We must not forget that millions of people are suffering from poverty, injustice and ignorance. We must not forget that millions of children are out of schools. We must not forget that our sisters and brothers are waiting for a bright peaceful future. So let us wage a global struggle against illiteracy, poverty and terrorism and let us pick up our books and pens. They are our most powerful weapons. One child, one teacher, one pen and one book can change the world.19

LEGACY AND CRITICISM

Malala is still writing her story. It is too early to say what her final legacy will be. Yet parts of the picture are clear. In her speech to the United Nations, she asked for world leaders to pursue peace deals that protect the dignity and rights of women and children, for free compulsory education for every child on the planet, for support from developed nations for educational opportunities for girls in the developing world, and for freedom and equality for all women. She also called on governments to take action against terrorism and violence and for all communities to “reject prejudice based on caste, creed, sect, religion or gender.”20 These points form the foundation of her moral vision.

No matter what she does with the rest of her life, she will always be remembered as a voice for education, specifically the education of girls. She believes education is a human right. When Taliban allies insisted that she wished to indoctrinate students into Western ways, she replied, “Education is education. We should learn everything and then choose which path to follow. Education is neither Eastern nor Western, it is human.”21

Malala challenges those willing to overlook glaring disparities in access to education. “It is not time to tell the world leaders to realise how important education is—they already know it—their own children are in good schools,” she told the Nobel Committee. “Now it is time to call them to take action for the rest of the world’s children.”22 In public appearances, she critiques people who think basic literacy is sufficient for the children of the poor but want advanced math and science for their own kids. She also directly confronts those who claim her goals of worldwide education are idealistic and untethered from the realities of cost, feasibility, and effectiveness. She asked the world leaders assembled in Oslo, “Why is it that countries which we call ‘strong’ are so powerful in creating wars but are so weak in bringing peace? Why is it that giving guns is so easy but giving books is so hard? Why is it, why is it that making tanks is so easy, but building schools is so hard?”23

Human society the world over still fails to recognize the full human dignity of more than half the human race: women. The underlying cause is the same whether prejudice takes the form of pay disparities or sexual violence, slavery, or limits on personal freedom. Malala encourages women to fight back. “There was a time when women social activists asked men to stand up for their rights,” Malala told the United Nations. “But, this time, we will do it by ourselves.”24 Studies have shown that the most powerful intervention in poor communities is to provide education, independence, and financial resources to women.25 Malala looks past these utilitarian grounds to moral ones, and her life story thus becomes an inspiration to all those wondering whether fighting would make a difference. “There is a saying in the Quran, ‘The falsehood has to go and the truth will prevail,’” she writes in her autobiography. “If one man, Fazlullah, can destroy everything, why can’t one girl change it?”26

We live in an era of rising prejudice, hate, and misunderstanding of Islam in the West, and a clash-of-cultures mentality within some Muslim communities. Malala is a focal point for interfaith dialogue. It would be unfair to make Malala a spokesperson for the world’s Muslims. Yet she is more representative of her fellow Muslims than are extremists such as the Taliban.

Every faith faces internal battles with authoritarian and often violent fundamentalists within its ranks. The struggle today is not between secularism and backward religion but within religions themselves over whether misguided people will get away with twisting words of faith and love to glorify themselves and do violence to others. The Taliban makes every effort to paint Malala as a bad Muslim—claiming that the attempt on her life was because she was promoting secularism and citing an interview in which she listed as role models not only Benazir Bhutto but also former US president Barack Obama, one of the militants’ chief enemies.

When Malala was young, friends and family criticized Malala’s father, Ziauddin. It was he who ran the school she attended and refused to stop educating girls. It was he who campaigned against the Taliban and criticized the mullahs as being dangerous purveyors of poor interpretations of the faith. Friends, family, and outside observers thought Ziauddin was putting Malala in danger. Whether he allowed Malala to speak out or pushed her to do so, the result was that his daughter was in harm’s way. But when Ziauddin started to blame himself for making Malala a target, it was Malala’s mother who sharply insisted, “You never groomed her to become a criminal or a terrorist. She stood for a noble cause.”27

Her relative youth and inexperience raise questions. Her commitment to education mirrors her father’s. Has she merely embraced his cause as her own in the midst of a turbulent childhood? Would the world know her name if the Taliban had not tried to kill her? She just recently began university studies, a time when many young people challenge and change their own beliefs. Will her vision remain the same?

Malala became famous challenging radicals in her own tradition. Yet as a conservative Muslim, she is an unlikely hero for secular audiences or Western countries prone to anti-Islam hysteria. She fits neatly in no category. For instance, even though she is a longtime advocate for women and girls, she faced criticism for at first refusing to use the word “feminist.” She then encountered a different backlash after embracing the “tricky word” and declaring, “Feminism is another word for equality.”28 Malala is easily criticized for the same reason she is compelling: she is young, her views are evolving, and she is trying to stand with feet planted in two worlds that seem to be moving farther apart. That is the burden that will rest on Malala’s shoulders in the years to come.

Malala is not universally popular back home in Pakistan. At first, the attempt on her life provoked a groundswell of support. In the years since, it has largely faded. Some ill will toward her stems from geopolitical issues. The attention on Malala conveniently paints only the Taliban as monsters, ignoring the death toll of Western and US-led military interventions, including drone strikes that often claim the lives of innocent bystanders. Given the role of Western governments in creating the Taliban, supporting Pakistani dictatorships, and destabilizing the region, many rightly point out that attention on Malala could serve as a distraction from Western complicity in the ongoing turmoil in that part of the world.

Others turn their ire on Malala and her family. Some claim that the West loves Malala only for her areas of disagreement with some Muslims, turning her into a secular heroine and another chance for Western people to claim the superiority of their values. The family has come under fire for not returning to Pakistan (until 2018), despite the death threats, and for their now-comfortable Western lifestyle. Her family’s success reminds many of the lack of social mobility for millions in Pakistan, and her celebrity makes some ask why other victims of the Taliban are not given equal love and honor. Finally, mirroring the way those in Kolkata feel about Mother Teresa, some Pakistanis believe that she shames Pakistan by shining a light on problems it shares with many countries.

If there is a measure of truth in any of this, it seems the blame lies with the West’s rush to embrace Malala and not with the young woman herself. Malala is an example of how extraordinary people can rise above their circumstances and create heroic change. She is also a reminder that political decisions made thousands of miles away can have real and destructive ramifications on the lives of millions. We write this book in the United States, a nation that hovers behind the scenes of Malala’s story, never far removed from the bloodshed and terror that Malala experienced. If Malala’s stand for education is to mean anything, it should encourage people to educate themselves on what their country’s policies will mean in the lives of people half a world away. We can admire the woman and look at underlying causes. Her cry for education would insist we do both.

While Malala was still lying in her hospital bed, the Muslim chaplain at the hospital told her of the outpouring of love from around the world. “Rehanna told me that thousands and millions of people and children had supported me and prayed for me,” Malala writes. “Then I realized that people had saved my life. I had been spared for a reason.”29 We do not yet know what Malala’s full legacy will be. A man fired three shots at a group of young girls and failed to kill anyone. His target, Malala, survived despite being shot in the face. She continues to captivate the world today. It all adds up to a sense of the miraculous—that perhaps God is working in the world by keeping her around. Here is someone spared to advance a sacred mission that is not yet complete.

LEADERSHIP LESSONS

Malala Yousafzai’s life and work offer a number of important lessons about moral leadership:

- Never underestimate family. We have talked about the importance of family for every leader, and Malala is a quintessential example. Consider what lessons and values you inherited from your own family.

- Unearned suffering is redemptive. We should never make an idol out of suffering. Nevertheless, there is something about innocents who suffer for no reason that compels us to act. The fact that Malala was so young heightened global moral sympathy for her.

- Combine gifts and practice. Malala was always bright, articulate, and a natural leader. She also practiced writing and delivering speeches in school, and had experience with press and government officials, all of which left her poised beyond her years when she suddenly became a global figure.

- Faith traditions are contested. It is important to distinguish between different versions of the “same” faith. All faiths are contested. We dare not make sweeping generalizations about other religions. Many of the moral leaders in this book strove to articulate a different version of faith from the one popular in the society around them.

- Don’t underestimate young people. The world is biased against the very old and the very young. Defenders of the status quo often dismiss reform movements as the work of kids who will one day see the light. On the contrary, young people ask questions and pose answers that shake up moribund systems.

Malala Yousafzai is the only leader in this volume who is still alive today. Including a living leader carries some amount of risk. Moral leaders are, after all, as prone to failure, weakness, blind spots, and wrongheaded decisions as the rest of us. Other leaders have lived long enough to tarnish their legacies. We hope that will not be the case for Malala. We are optimistic because, while young, she has been remarkably consistent and unflinching.

She has already accomplished so much, yet she admits that she is just getting started. “People prayed to God to spare me, and I was spared for a reason—to use my life for helping people,” she wrote in her autobiography.30 She concludes:

I love my God. I thank my Allah. . . . By giving me this height to reach people, he has also given me great responsibilities. Peace in every home, every street, every village, every country—this is my dream. Education for every boy and every girl in the world. To sit down on a chair and read my books with all my friends at school is my right. To see each and every human being with a smile of happiness is my wish. I am Malala. My world has changed but I have not.31

We await the next chapter in the life of the girl from the Swat Valley who became an international inspiration—and a moral leader worth studying.

DISCUSSION QUESTIONS

- Describe the role Malala’s father, Ziauddin, played in her life. What do you like or dislike?

- How does Malala’s faith differ from the religious ideas of the Taliban?

- Check recent news for coverage of Malala since this book was published. Does it fit with what you already know? Differ?

- Did Malala’s youth help or hurt her cause?

- Search the internet for and watch a video of an interview of Malala. What do you find most striking listening to her speak?

FOR FURTHER READING

He Named Me Malala [documentary], directed by Davis Guggenheim. Fox Searchlight Pictures, 2015.

Yousafzai, Malala. “Address to the United Nations.” The United Nations, July 12, 2013. http://www.un.org/News/dh/infocus/malala_speach.pdf.

———. I Am Malala: The Girl Who Stood Up for Education and Was Shot by the Taliban. New York: Back Bay Books, 2013.

———. “Nobel Lecture.” Nobelprize.org. Nobel Media AB, December 10, 2014. https://www.nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/peace/laureates/2014/yousafzai-lecture_en.html.

1. Malala Yousafzai, “Address to the United Nations,” The United Nations, July 12, 2013, http://www.un.org/News/dh/infocus/malala_speach.pdf.

2. Malala Yousafzai, I Am Malala: The Girl Who Stood Up for Education and Was Shot by the Taliban (New York: Back Bay Books, 2013), 25.

3. Malala Yousafzai, “Nobel Lecture,” Nobelprize.org, Nobel Media AB, December 10, 2014, https://www.nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/peace/laureates/2014/yousafzai-lecture_en.html.

4. Yousafzai, I Am Malala, 18.

5. Yousafzai, I Am Malala, 71–72.

6. Yousafzai, “Nobel Lecture.”

7. Yousafzai, “Nobel Lecture.”

8. Malala Yousafzai, in documentary He Named Me Malala, directed by Davis Guggenheim, Fox Searchlight Pictures, 2015.

9. Yousafzai, “Nobel Lecture.”

10. Yousafzai, “Address to the United Nations.”

11. Yousafzai, I Am Malala, 133.

12. Yousafzai, I Am Malala, 214.

13. Yousafzai, I Am Malala, 224–25.

14. Yousafzai, I Am Malala, 237.

15. Yousafzai, “Nobel Lecture.”

16. Yousafzai, I Am Malala, 242.

17. Yousafzai, I Am Malala, 263.

18. Yousafzai, “Address to the United Nations.”

19. Yousafzai, “Address to the United Nations.”

20. Yousafzai, “Address to the United Nations.”

21. Yousafzai, I Am Malala, 162.

22. Yousafzai, “Nobel Lecture.”

23. Yousafzai, “Nobel Lecture.”

24. Yousafzai, “Address to the United Nations.”

25. Center for High Impact Philanthropy, “The XX Factor: A Comprehensive Framework for Improving the Lives of Women and Girls,” The University of Pennsylvania, 2017, https://www.impact.upenn.edu/the-xx-factor/.

26. Yousafzai, I Am Malala, 142–43.

27. Abdul Hai Kaka, “The Wind beneath Her Wings: A Look at the Family behind Malala,” RadioFreeEurope/RadioLiberty, November 5, 2013, https://www.rferl.org/a/pakistan-gandhara-malala-family/25159006.html.

28. Press Association, “Malala Yousafzai Tells Emma Watson: I’m a Feminist Thanks to You,” The Guardian, November 5, 2015, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/nov/05/malala-yousafzai-tells-emma-watson-im-a-feminist-thanks-to-you.

29. Yousafzai, I Am Malala, 288.

30. Yousafzai, I Am Malala, 301.

31. Yousafzai, I Am Malala, 313.