Ch. 10

SWORD-FISH AND LIVELY GROUNDS

They supposed a sword-fish had stabbed her, gentlemen.

Ishmael, “The Town Ho’s Story”

After the Pequod rounds the Cape of Good Hope, Ishmael begins the long yarn “The Town Ho’s Story” with a whaleship leaking: “they supposed a sword-fish had stabbed her.”1 Melville was fascinated with swordfish (Xiphias gladius). In Mardi, he wrote an entire chapter about this animal, extolling its solitary warrior characteristics and satirizing scientific attempts at classification, working through some ideas he’d later use to explore the cetology of the sperm whale.

To explore Ishmael’s yarn, I turned to Linda Greenlaw, swordfisherman and author, to find out what she thinks of actual nineteenth-century reports of swordfish stabbing holes into wood hulls.

“It’s hard to believe,” she says. “And I’ll tell you why. Swordfish go after prey with their bill. They do use it as a weapon. But they don’t stab. They slash with it. Right? They’re not going to swim at something and skewer it. When they swim through a school of fish, they slash, and then they come back and eat what they’ve injured. I’ve seen many swordfish fighting on a hook, and: it’s this.” She motioned a flat hand side to side, as if aggressively dusting off the table. “When you land them on the deck of a boat: it’s this.”2

Greenlaw goes back to holding her mug of tea. We’re in her dining room in Maine.

“It’s like a shark when they latch onto something, and they shake their head,” she continues. “Now, could a swordfish slash at a wooden boat and happen to pierce it? I mean, I guess if the boat were really tender. I was never ever, ever nervous about a boat being hurt, damaged, by a fish—even when I was on my first boat, which was wood. Obviously, I can’t say it’s never happened. ‘Course, maybe it did.”

And, amazingly, it did.

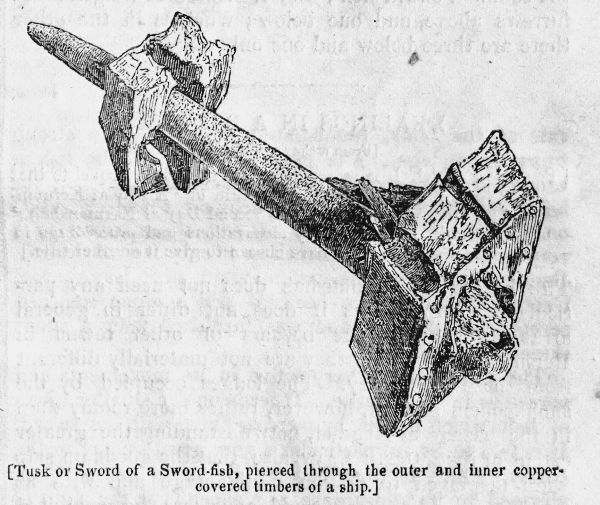

Before sitting down to write Moby-Dick, Melville had heard of swordfish or other billfish stabbing into the hulls of wood vessels. By the nineteenth century, some sailors and naturalists had differentiated between swordfish and the billfish, the latter being the marlin and sailfish now in the family Istiophoridae. But for Melville and other fellow whalemen “sword-fish” could really have referred to any of these large predatory fish with a long bill. (See earlier fig. 3.) Baron Cuvier, in his volume on fish that Melville owned and marked up, mentions swordfish, sailfish, and sawfish all recorded leaving a bill or two in wood hulls. Melville might have read about such an instance in Liverpool in 1839 when he was ashore during his first voyage. A piece of wood from the ship Priscilla that had a swordfish bill rammed through the outer planking was on display. In 1840 Dr. Bennett wrote an account of the Foxhound, a whaleship that had a swordfish bill stuck through the protective copper underneath the ship’s water line. As with the Priscilla, the fish’s bill broke off like a bee’s stinger and remained in the ship’s plank from the South Seas all the way home. Two years later, when Melville was ashore in the Marquesas, a whaleship named the London Packet had to haul out in that harbor to make repairs to a leak that they believed was caused by a billfish. At the Natural History Museum in London is a hunk of ship’s timber from about 1832, near the width and length of your shin, which had been stabbed by two separate marlin right next to each other—and the pieces of bill are still stuck in the wood. It’s almost certain that Melville saw this exact piece of wood when he toured the British Museum on his trip to London just before he began writing Moby-Dick. Perhaps the image stuck with him? I’ve held that chunk of wood myself. The bills are wedged into the fibers as if driven with a sledgehammer. The rostra come in at different angles. I could still see where the copper sheathing had once been nailed over—which the bills had pierced straight through.3 (See fig. 23.)

FIG. 23. A swordfish bill speared through ship timbers, as illustrated in the Penny Magazine (1835).

So the part about a swordfish causing a leak in a wooden whaleship is not a stretch in Ishmael’s yarn “The Town Ho’s Story,” although it was a matter of fascination among mariners and the public at the time. We know of no actual sinkings by swordfish, marlin, or sailfish bills, but they definitely pierced the wood hulls of sailing ships.

Why these fish stick into the hulls of ships remains a mystery. Even mariners and biologists today still do not have a good understanding of how swordfish might use their bills—if the extended rostra have evolved for anything other than for slashing smaller fish for food or as a deterrence from predation at the mouths of sharks and killer whales. Swordfish have relatively small mouths. Greenlaw explains that they barely have teeth, so they gulp up the chunks of fish they’ve slashed up. Their bills, on both males and females, can grow to a third of their total length. Swordfish can weigh over 1,100 pounds and, according to a recent study by a team of scientists in Taiwan who study propulsion dynamics, swordfish can swim nearly eighty miles per hour, faster than any other fish in the world.4

In “Cetology,” Ishmael implies a knowledge of the swordfish’s use of its bill, but he never follows through with what he thinks that is exactly. Dr. Bennett observed from his ship’s rail in the 1830s, however, exactly what Greenlaw explains: swordfish slashing back and forth through a school of smaller fish. Thus, might a reasonable explanation be that they stab a hull accidentally when slashing through a school of fish congregating under a slow-moving ship in the open ocean?

Greenlaw isn’t sure. She says that swordfish are always aware of a boat’s hull. And when she’s examined the stomachs of swordfish, it seems their diet is primarily deepwater fish and squid. Swordfish usually are not interested in a few surface schooling fish.

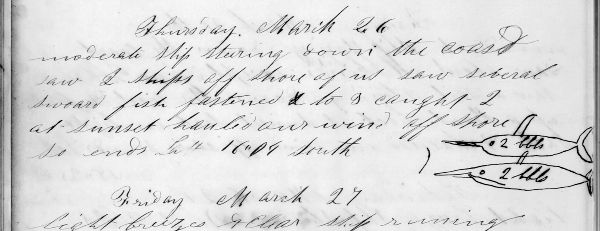

American whalemen sometimes rowed up and harpooned swordfish from their boats for food or entertainment, or to practice their harpooning skills. The largest of fish were even sliced up and put in the try works to yield a couple gallons of oil. Baron Cuvier in 1834 wrote that harpooning for swordfish was “precisely the whale fishery in miniature.” In January 1844, for example, the men of the Charles W. Morgan lowered after swordfish and caught one off the coast of Peru—while Melville was sailing homeward bound in the same region aboard the United States. Two years later, also off the Peruvian coast, the men of the Commodore Morris harpooned three swordfish and were able to capture two of them. Beside this entry the logkeeper drew the swordfish and marked that they got two barrels of oil from each (see fig. 24).5

FIG. 24. Logbook entry from the whaleship Commodore Morris, recording the capture of two swordfish, which they boiled out for oil (1846).

Whalemen could row fast enough to catch a swordfish?

“Sure,” Greenlaw says. “Now that I believe. If you know what you’re doing. In most parts of the world it’s rare for swordfish to hang out at the surface. But if you’re in an area like Georges Bank or off Nova Scotia where they do surface, and you go on them the right way, it’s not that difficult to harpoon them. When they’re on the surface, they’re kind of lolly-gagging along.”

At the time, Surgeon Beale and his fellow naturalists, along with the whalemen, believed that swordfish were predators on great whales, or at the very least an annoyance. Beale wrote of part of a swordfish bill impaled in the body of a beached whale in Yorkshire, England, and he also discussed a theory that sperm whales might breach to escape these fish. In 1856 artist-whaleman Robert Weir wrote in his journal: “Saw a very large sword fish this morning, that deadly enemy of the Sperm Whale. That is excepting ourselves and other whalemen.”6

Twenty-first-century biologists do not believe that swordfish are predators of whales, or even of dolphins or small porpoises, although they concede that very occasionally a billfish might injure a marine mammal for reasons still unknown. It’s more likely the other way around. Sperm whales, or more commonly orcas, will occasionally eat a swordfish or two. Yet swordfish interactions with whales and ship hulls are still not explained. Recent underwater video has recorded swordfish and marlin attacking oil rigs and getting their bills stuck in pipelines. In 1967, at the depth of 2,000 feet, a large swordfish mortally impaled itself into an edge of the steel submersible Alvin, and it remains a mystery as to why.7

LIVELY GROUNDS AND SHIFTING BASELINES

American whalemen of the nineteenth century observed fish at sea regularly, especially in prolific areas like the Peru Current off South America. Here the abundance of plankton supports baleen whales directly and sperm whales indirectly by feeding squid and swordfish, marlin, and shark populations. Highly productive waters like those off the west coast of South America also provide food for enormous schools of anchovetas (Engraulis ringens), which in turn feed baleen whales and enormous populations of seabirds, a range of medium-sized fish, such as mahi-mahi, several species of tuna, and then the billfish.

In “Stubb kills a Whale,” Ishmael identifies the coast off Peru as a “lively ground,” an ocean region loaded with flying fish, mahi-mahi, and “other vivacious denizens.” Scientists today believe that these regions were once even far more lively than they are now, in part because of the effects of American whaling, but more so due to the large-scale industrial fishing of the second half of the twentieth century. Only in the 1850s, largely begun by zoologist Karl Ernst von Baer in Russia, did naturalists begin to examine and encourage the keeping of fisheries data in terms of catches, location, season, and fishing gear. Baer combed historical resources from monasteries to the archives of local governments in order to understand what was actually present in the past. He pushed for centralized, long-term data for the future. Even in 1854, Baer described what we now refer to as the shifting baseline: that past natural environments always seem more prolific—the fish “back then” were always more numerous and larger.8

The anecdotal reports of the Pacific from trusted sources, like Surgeon Beale, certainly suggest a more populous ocean in the southeastern Pacific. Beale wrote of schools of hundreds of swordfish. Once off the coast of Chile he described just how prolific the waters were in which his whaleship sailed:

The irregular and desert shore hemmed in the great ocean, which now swarmed with living creatures. The humpbacked whale sported in the smooth water, his polished skin glistening in the rays of the scorching sun; seals also, at a small distance from the shore, were lying as if asleep upon the surface, basking in the heat. Hundreds of large albacore and bonito [two species of tuna] now crowded our vessel, and gave employment to those who could be spared from the duties of the ship, in catching them with the hook. The ugly sun-fish [Mola sp.] now and then came floating by, and gave the young harpooner a chance of shewing his newly-acquired dexterity, by plunging the barbed iron into their grisly bodies. The ferocious sword-fish frequently shewed himself, much to the terror of the bonito and albacore, which shot through the fluid element with wonderful velocity, to escape from their voracious pursuers. The varieties of polypi [squid/octopus] and medusæ [jellyfish] which abound here are immense, and would find the naturalist with employment for a century.9

From his natural theological ship’s rail, Beale recorded miles of seabirds flying over the sea and a variety of species along the coast—flamingoes, cormorants, penguins, and pelicans—all of which, he said, reflect on “the wisdom and greatness of Him . . . to animate the wilderness.”10

The perspective and knowledge of Linda Greenlaw, one of the most successful fishermen in modern day New England, has much to teach us about Ishmael’s views in Moby-Dick. Greenlaw wrote in Seaworthy that harpooning swordfish from the bow of a boat is “the most primitive and fundamental” way to kill these animals. She thought the “frenzied sensation” might be a feeling she shared with “the whalers of old.” Although Greenlaw received a liberal arts college education, she sees her real education in life at sea. Greenlaw simply loves to fish—swordfish, tuna, lobster, halibut. As a twenty-first-century commercial hunter, she has little spiritual or cultural connection to fish. She has fished in some of the roughest weather to support herself and the families of the men whom she leads. Her self-respect, her identity, is in putting food on people’s tables. Greenlaw tells me she learns about the biology of marine animals to help her catch more fish and to do so before the other fishermen can. Modern fisheries biologists have been of little help to her, she says. Similar to Ishmael’s perspective on the naturalists ashore in 1851, Greenlaw wrote in 2010: “I had read most of the small amount of literature available on the biology of swordfish, and some of it is contradictory, indicating how little is actually known. Personal experience and observations through the course of my twenty-year work-study had taught me most of what I know about the behavior of swordfish.”11

In this way, little has changed since the nineteenth century in terms of a divide between the fishermen who are out there every day and the scientists studying the matter with more limited experience on the water. The more significant difference, which Melville would never have considered, is that scientists now have a voice in managing fisheries—an idea that grates on Greenlaw.

Melville would, however, have been able to identify with how in her books Greenlaw wants the reader to know the blood, sweat, and tears that go into the fish that you’re plopping on your grill. In 1816 Sir Walter Scott famously wrote a character in The Antiquary who said: “It’s no fish ye’re buying—it’s men’s lives.” Melville followed in kind when in “The Affidavit” Ishmael says: “For God’s sake, be economical with your lamps and candles! not a gallon you burn, but at least one drop of man’s blood was spilled for it.”12