Ch. 14

FRESH FARE

Yet now and then you find some of these Nantucketers who have a genuine relish for that particular part of the Sperm Whale designated by Stubb; comprising the tapering extremity of the body.

Ishmael, “Stubb’s Supper”

While the sharks are eating whale meat above, sharkish Stubb is eating a whale steak, a piece from near the animal’s tail. In “The Whale as a Dish,” Ishmael opens with the declaration: “That mortal man should feed upon the creature that feeds his lamp, and, like Stubb, eat him by his own light, as you may say; this seems so outlandish a thing that one must needs go a little into the history and philosophy of it.”1

THE WHALEMAN’S DIET

Whalemen under sail in the 1840s and ’50s ate mostly salted beef and pork, salted cod, hard biscuit, rice, and a regional collection of vegetables that would not spoil as quickly, such as potatoes, onions, squashes, and beans. They had molasses as a sweetener for weekly “duff.” They drank water and coffee. By Melville’s time, scurvy was largely a disease of the past, even on lengthy voyages with few port stops. In “The Decanter,” Ishmael jokes about scurvy when describing hardtack with weevils: “The bread—but that couldn’t be helped; besides, it was an anti-scorbutic; in short, the bread contained the only fresh fare they had.”2

Moby-Dick is piled high with discussions of food, beginning immediately with “Loomings” and Ishmael’s comic mumblings about broiled fowl, continuing all the way through to “The Decanter,” in which he extols the virtues of the food on British whaleships (despite the rotten bread). How well the whalemen ate in terms of volume and quality on these ships is a matter for scholarly debate. One morning, as we toured the galley of the Charles W. Morgan, food historian Sandy Oliver tells me she thinks the records of the men served bread infested with cockroaches and weevils are true, but did not occur as often as it’s represented today. It made no sense to have men weak and unable to hunt effectively. On the other hand, some scholars believe that whaleship owners were more often penny-pinchers, like Peleg and Bildad, so that the desire for more and better food was the primary motivation for desertion by the time whalemen arrived in the Pacific. In the first paragraph of Melville’s very first book, the opening to Typee in which he brags about his six months at sea, he laments the loss of their fresh bananas, sweet potatoes, yams, and delicious oranges: “There is nothing left us but salt-horse and sea-biscuit.” (Seaman told stories of occasionally being fed horsemeat—Ishmael jokes in Moby-Dick that it can be camel—but the salted meat they normally ate was cow beef.) Most whaleship captains by midcentury, however, planned enough to acquire fruits and vegetables to supplement the seamen’s diet. They thought ahead along their network of suppliers for fresh food and water at a range of trading posts that had been established for whalemen all across the islands of the Pacific. For example, when Melville escaped from his Tahitian jail after his second whaleship, he worked on a farm in Moorea that cultivated sweet potatoes, taro, yams, and sugar cane.3

A half century earlier, when whalemen first began hunting in the Pacific, the food networks were far more sparse and scurvy was still a major concern. The most illuminating of Melville’s fish documents about sailor-fare was that by James Colnett of the Royal Navy, the same captain who reported on eighteen- to twenty-foot sharks. In 1798, Colnett published the narrative of his Pacific voyage, funded in part by the Enderby whaling family in order to gather information for whaling voyages. It was Colnett’s illustration of a sperm whale with an enormous eye that Ishmael ridicules in “Monstrous Pictures of Whales” (see fig. 28). Colnett had learned the importance of crew health as a midshipman on James Cook’s second circumnavigation, and a significant part of the mission of Colnett’s voyage in the 1790s seems to have been to plan for food for the future whaling fleet.4

FIG. 28. James Colnett’s cub sperm whale and diagram for cutting into a whale (1798), which Ishmael ridicules because of the enormous eye.

Colnett sailed from England with two live cows and regularly kept pigs and chickens on board. When anchoring besides islands or along coasts in the Pacific, the men of the Rattler ate a variety of fish species. They also ate coconuts, fruit of the “molie tree,” shellfish, a variety of sea and land birds, as well as the Ancient Mariner’s sea snakes—in the belly of which they found more fish. They ate “alligator,” which was more likely crocodile. They shot two or three monkeys, presumably for food. They made soup from turtles and from large flocks of sea ducks (Anas spp.). With a Spanish ship, Colnett traded for pumpkin, chickens, two sheep, two bags of bread, and twelve (presumably beef) tongues. On the Galápagos, they captured the immense Galápagos tortoises (Chelonoidis spp.), animals that were just beginning to be discovered by the whalemen, who would go on to capture these reptiles by the thousands, precipitating the loss of three species to extinction and leaving the rest vulnerable or critically endangered. Colnett wrote that the tortoise “was considered by all of us as the most delicious food we had ever tasted.” Ishmael refers to them as “Gallipagos terrapin,” and Melville likely heaved a few himself off the islands while aboard the Acushnet. Whalemen kept these tortoises alive for months aboard ship to provide fresh meat. On Cocos Island (now a national park of Costa Rica), Colnett ordered the introduction of a pair of pigs and goats. Rats, unfortunately, were already well established on Cocos. In another bay on Cocos Island he had his seamen plant “garden seeds, of every kind.”5

While out whaling at sea, they ate “sun-fish” (Mola spp.). They ate “devil-fish,” which were likely rays. The crew of the Rattler also “saw dolphins and porpoises in abundance, and took many of the latter, which we mixed with salt pork, and made excellent sausages.” For men who had scurvy symptoms, Colnett gave them preserved fruits, pickles, fresh bread, and three times a day “twenty drops of elixir of vitriol, and half a pint of wine.” The men recovered.6

A half century later, by Melville’s day, whalemen like Captain Lawrence on the Commodore Morris had far more options for fresh food around the Pacific. After rounding Cape Horn, Lawrence sailed to Mocha Island in 1850 to load up two barrels of potatoes, five pigs (who would later have piglets), two roosters, and twenty-five pumpkins. At other islands throughout the voyage, Lawrence’s crew captured, gathered, or traded for fish, peaches, yams, and the eggs of “mutton birds [likely shearwaters, Puffinus spp.], which are very good eating they resemble a hens egg.” On the “Nancytucket Island” of the South Pacific, his seaman collected about a “half barrel of gulls eggs and eight curlews.” At one point Lawrence flogged the cook for “wasting provision.”7

In short, the diet of American whalemen in the mid-nineteenth century was mostly salted meat and bread, but it was also varied and regularly mixed with fresh meat, fruits, and vegetables whenever possible.

DID NINETEENTH-CENTURY WHALEMEN EAT WHALE?

Like Colnett’s crew, the whalemen of the Charles W. Morgan and the other whaleships captured and ate a variety of smaller toothed whales, such as dolphins and pilot whales.8 (See fig. 29.)

FIG 29. Whaleman Thomas White’s watercolor of harpooning dolphins from the bowsprit aboard the Sunbeam (1862), standing on the part of the ship often known as the “dolphin striker” (although this name is likely more for the iron point that might hit a dolphin that was bow-riding). In color, this image shows a splash of red blood underneath the dolphin just beneath the men.

Reverend Cheever wrote that, “as every one knows,” the whalemen harpooned and ate dolphin, known as “sea beef.” The cook used the dolphin oil for cooking. Robert Weir wrote that dolphin meat tasted like veal. John Jones, the steward of the whaleship Eliza Adams, wrote in 1852: “Got orders to make 10 000 balls of it,” referring to meat from seven pilot whales killed off Cape Horn. Thus true to culinary life at sea, Ishmael in Moby-Dick extols the flavor of dolphin meat and explains that many people, including the monks in Scotland, have enjoyed meatballs made of porpoise.9

Yet for all of that diversity of diet, need for fresh food, and regular eating of smaller marine mammals, there is less evidence that whalemen like Stubb actually ate the meat from the larger cetaceans with a “genuine relish,” especially meat from their regular catch of sperm or right whales. Ishmael puns accurately that Stubb’s taste is rare, but it was not unprecedented. Ishmael says he liked to fry ship’s biscuit in the oil of the tryworks. Melville likely buttressed his own experience and developed some of his foodie ideas—and the relish pun—from J. Ross Browne, who wrote of “delicious” whale oil biscuits during night-watches, as well as the frying up of sperm whale brains. Browne wrote, too, that “certain portions of the whale’s flesh are also eaten with relish, though, to my thinking, not a very great luxury, being coarse and strong.” Browne added that whale meat was better mixed with potatoes, like the porpoise balls, but was gobbled up by the men just for the variety, just as they’d eat “with as much relish” roast beef back on land.10

Cruising up in the Arctic for bowheads, Scoresby wrote that if whale meat was cleared of fat, broiled, and seasoned with salt and pepper, it was “not unlike coarse beef.” Like other whalemen, Captain Scoresby recommended the meat from younger whales, or at least the more tender parts. Dr. Bennett, for his part, described the delicacy of meat from small humpback whales. Scoresby heard whale breast milk is “well-flavoured,” and it was Bennett who wrote about sampling this milk: “it has a very rich taste.” In turn, Ishmael mentions that whale milk is “very sweet and rich,” adding that “it might do well with strawberries.” Whaleman-artist John F. Martin wrote in his journal about frying pieces of the right whale’s lip: “When eaten with pepper & vinegar it tastes very much like soused tripe.”11

Aboard Colnett’s Rattler, the men ate the heart of a young sperm whale—the very same one that was the model for the outline with the large eye. Colnett’s cook baked the heart into a “sea-pye,” which “afforded an excellent meal.” Even as late as 1912, Robert Cushman Murphy, a naturalist aboard an American whaleship, reported their chef making a meal of dolphin fish, sperm whale balls, and baked beans.12

So why, if it was so available, was whale meat not an even more regular, even daily part of their diet? If they had chosen to, the whalemen could have surely smoked, dried, or salted the meat. A large portion of the men would have had experience with this from farm and coastal fishing work.

Ishmael takes up the question in “The Whale as a Dish,” in which most of the history appears accurate. Ishmael explains that despite the long and royal tradition of eating whale meat, American whalemen did not eat it regularly, beyond dolphins and pilot whales, because there was just too much of it all at once during the butchering process, and that whale meat on the whole was just too fatty and rich for their taste. Sperm whale muscle is a dark, red meat filled with the myoglobin that enables the whale to dive so deeply. Even today, baleen whales, such as the minkes eaten in Iceland, are known to taste better. Only the Japanese and small pockets of Indonesians, historically and presently, have eaten sperm whale on a regular basis.13

Melville’s use of whale meat for the novel works in part to tickle perceptions of the exotic. The author knew, as is still often the case today, that whale meat is stigmatized as for only the uncivilized, the sharkish. This Melville implies with Queequeg and subsequently with Stubb, as well as with his story of the British whalemen forced to eat whale in the polar regions—as if those men had lowered themselves to the level of the Eskimo. Environmental historian Nancy Shoemaker found that many of the sailors considered eating whale meat too savage, too otherly. They’d try it once or twice to have the story to tell back home, or even if they ate it often in some manner, they had no interest when they returned. Whale meat was considered food for Native Americans, Inuit, and Pacific Islanders. Ishmael explains early in the novel that even food cooked rare is heathenish and implies a taste for human flesh: “We will not speak of all Queequeg’s peculiarities here; how he eschewed coffee and hot rolls, and applied his undivided attention to beefsteaks, done rare.” Melville’s perception that whale meat was for savage tribes only strengthens the image of Stubb eating rare whale meat as sharklike—no better or worse than the sea animals gnawing at the freshly killed meat beside the Pequod.14

At home in the United States in the nineteenth century, whale meat was considered food for the lower classes. In Cape Cod, published serially beginning in 1855, Thoreau learned that local boys ate sandwiches with blubber from pilot whales driven onto the beach. An older fisherman said he actually preferred pilot whale meat to beef. Thoreau didn’t try it. In his narrative he quickly added that in previous decades in France “blackfish were used as food by the poor.” Thoreau’s implication here is that whale meat was a necessity of poverty. (It’s a fun, if surely coincidental, detail that Stubb is from Cape Cod.15)

As today, food avoidances and taste tended to be more often culturally driven social constructions, even if these choices might have had historical roots in logistics or health. In Melville’s America, of course, vegetarianism and more ethical eating was not as significant a movement as it is today, but Ishmael’s closing comments in “The Whale as a Dish,” certainly show these ideas had begun to arise. In “Cetology” Ishmael shows that we can hold opposing ideas together at the same time. The anthropomorphized playfulness of the “huzzah porpoise” reaches even the most hard-hearted of mariners: “He always swims in hilarious shoals . . . They are accounted a lucky omen. If you yourself can withstand three cheers at beholding these vivacious fish, then heaven help ye.” Then, immediately after this celebration of these animals, Ishmael explains that they make “good eating” and a plump porpoise will amount to about one gallon of “exceedingly valuable oil.” The sailors held a hunter’s reverence for a dolphin right alongside the desire to eat it or use it for daily living.16

Shoemaker explained that the modern debate over whaling is often about animal sentience and environmental ethics, but it’s also tied intricately with food, with taste, which extends across and beyond indigenous cultures, such as the bowhead and beluga-eating Inuit, and the industrial, high tech countries such as Japan, which sends its hunters all the way to the Antarctic to capture the meat. Both the Japanese and the Inuit can trace their hunting and eating of whales back over one thousand years.

Ishmael has two closing points in his “history and philosophy” of eating whale meat. The first, as we discussed earlier when talking swordfish, is to again remind the reader sitting comfortably at home to respect and recognize the whalemen out at sea, men who are in the ugly business of bringing home the whale oil. The second is to point out the hypocrisy of those ashore who might condescendingly judge those who choose to eat meat, use animal products, or even hunt the whales in the first place. This is an argument used by representatives of the current whaling nations—Japan, Norway, and Iceland—against those that judge the practice most vehemently: the people in animal-advocacy groups who use the products of animals such as cows and pigs in their daily lives, even while arguing the very cases against killing animals. Ishmael chides a fictional “Society for the Suppression of Cruelty to Ganders.” In 1840 Queen Victoria agreed to add “Royal” to the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals in England, and the SPCA had been active in England even then for about fifteen years, but there was yet no organized animal advocacy movement in the United States at the time of Moby-Dick. Whaling nations today ask why the United States can allow indigenous whaling from their own shores off Alaska, or, more significantly, why killing a “free range” minke whale, whose population seems stable and healthy in the North Atlantic according to both the IWC and the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species, is worse than tying up and fattening a baby cow for veal.17

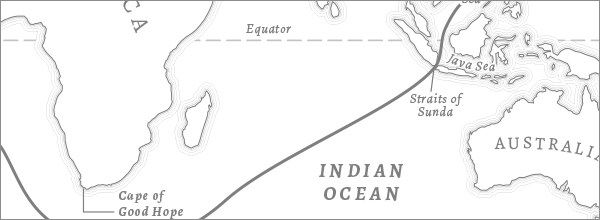

Deeper still, as the Pequod continues eastward in the Indian Ocean, Ishmael in “The Whale as a Dish” subtly equalizes humans and nonhuman animals: “Go to the meat-market of a Saturday night and see the crowds of live bipeds staring up at the long rows of dead quadrupeds. Does not that sight take a tooth out of the cannibal’s jaw? Cannibals? Who is not a cannibal?”

One sub-Arctic night in Reykjavík, Iceland, I am on my way down along the wharf to go on a whale watch when I notice, opposite the whale watch boat, two black-hulled ships named the Hvalur 8 and the Hvalur 9. The two whale hunting vessels, named for the whale, each have white masthead capsules for the lookouts, evolutions of Scoresby’s crow’s nests that Ishmael chides in “The Mast-Head.” Even at midnight it is light outside, because of the high latitude. On the whale watch we see a few minke whales in the distance, but otherwise it is a quiet ride out in the fjord beyond the capital. After we return to the dock, I hear some other tourists talking about finding a restaurant to dine on whale meat, despite walking past a large blue sign at the head of the wharf with a smiling cartoon whale that says: “Meet Us, Don’t Eat Us.” The sign is sponsored by the International Fund for Animal Welfare and the Icelandic Whale Watching Association, the latter of which advertises a list of local “whale friendly” restaurants that will not serve whale meat.18

The next day a painter working on Hvalur 8 tells me that the whale hunting boats are at the dock for repairs. They hunt on another part of the coast. According to the documentary Breach (2015), however, in previous years a whale watching vessel and a whale hunting ship were out on these waters of Hólmasund at the same time, within view of each other. Once the hunter boat steamed by with a couple dead whales dragged alongside in full view of the whale watchers. Tourists continue to eat whale meat in the restaurants in Reykjavík. Whale is eaten by some current Icelanders but it’s apparently not a meal that has deep roots in Icelandic culture. According to a 2017 report in the Iceland Review, sixty-five percent of the minke whale meat is sold to restaurants, primarily to tourists.19

I go to a restaurant that serves whale. But I chicken out.