Ch. 15

BARNACLES AND SEA CANDIES

No great and enduring volume can ever be written on the flea, although many there be who have tried it.

Ishmael, “The Fossil Whale”

Melville represented mid-nineteenth-century knowledge of small pelagic organisms in “Brit” and likely in “The Whiteness of the Whale” with his bioluminescent milky sea. In a few other scenes in the novel, Melville wrote of still more kinds of small invertebrates, notably barnacles and whale lice.

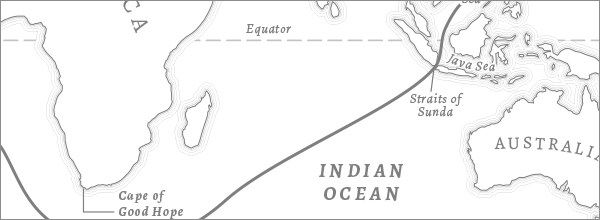

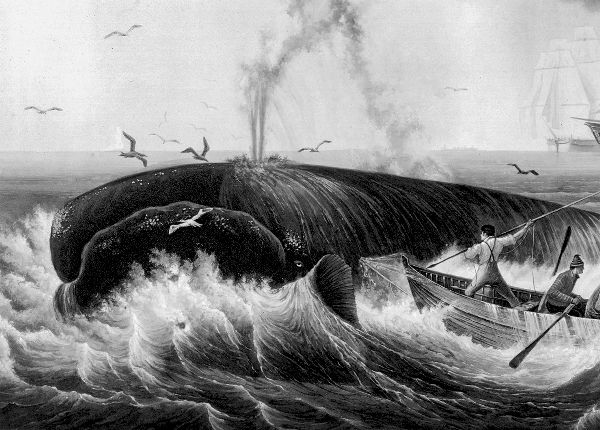

In “Cetology” Ishmael writes of the Pequod rolling on the waves “side by side with the barnacled hulls of the leviathan.” In “Less Erroneous Pictures of Whales,” Ishmael extols the vivacity and accuracy of a French painting by Ambroise Louis Garnery, which he believes properly depicts a right whale hunt, including where “sea fowls are pecking at the small crabs, shell-fish, and other sea candies and maccaroni, which the Right Whale sometimes carries on his pestilent back.” Ishmael gives far more detail, in fact, about the life on the whale’s head than is in the actual painting (see fig. 30).1

FIG 30. Detail of Pêche de la Baleine by Ambroise Louis Garnery (1835), engraved by Frédéric Martens, one of the paintings that Ishmael respects in “Less Erroneous Pictures of Whales.”

Later in the novel in the middle of the Indian Ocean, Ahab orders the men to kill a right whale and hack off the head to lash to the side of the Pequod, opposite a sperm whale’s head. Ishmael leads the reader over to the rail to look down on the little ecosystem on the right whale’s skin:

If you fix your eye upon this strange, crested, comb-like incrustation on the top of the mass—this green, barnacled thing, which the Greenlanders call the “crown,” and the Southern fishers the “bonnet” of the Right Whale . . . when you watch those live crabs that nestle here on this bonnet, such an idea will be almost sure to occur to you; unless, indeed, your fancy has been fixed by the technical term “crown” also bestowed upon it; in which case you will take great interest in thinking how this mighty monster is actually a diademed king of the sea, whose green crown has been put together for him in this marvellous manner.2

Biologists today refer to the patches of hard skin tissue that Ishmael calls the “bonnet” or “crown” as the whale’s callosities, a word less in use in Melville’s day regarding marine mammals. Modern scientists, beginning with the Soviet ecologist S. K. Klumov in the early 1960s, identify individual right whales by photographing this pattern of growth on their heads. Within the first several months of life each right whale develops a tough keratinized tissue on his or her lower lip, chin, above the eyes, and from the tip of the upper lip to back around the blowhole—similar to the locations of human facial hair. (See plate 4.) The callosities usually have, in fact, as Ishmael notes, a few hairs sprouting out from within. Once formed, the whale callosities are then colonized, especially by cyamids and barnacles.3

The cyamids, which Ishmael refers to as crabs and maybe also sea candies, were known to naturalists as “whale lice” or “crab lice,” a common name that’s still in use today. Although they indeed look like little crabs or even our own hair-infesting insects, cyamids are flattened amphipods. There are about forty species. They can be so host specific that researchers have used them as “tags” to help identify the historical and geographic separation of right whale species. Cyamids are about the size of your thumbnail. They have three pairs of back legs evolved to dig and hook into the whale’s skin.4

Barnacles also live on the right whale’s callosities. Perhaps twenty or so species of “whale barnacles” (of the subclass Cirripedia) may live on a variety of marine mammals. In order to hang on, the Tubicenella major barnacle, which is common on the southern right whale, builds an accordion-style column of shell that burrows deeply into the callosity. The gorgeous Coronula diadema barnacle has evolved a distinct hexagonal opening. Linnaeus gave this species its scientific name in the eighteenth century. Darwin identified and named its close relative in 1854, Coronula reginae. If Melville knew the genus name, he worked it into his puns in “The Right Whale’s Head,” appreciating the Latin reference to crown.5

Cyamids and barnacles feed off scraps from their whale hosts as well as phytoplankton floating past. Cyamids also eat flakes of the whale’s skin. Although there’s little evidence that barnacles and cyamids do any real harm to the whale, either of these hitchhikers can introduce irritation and, just like on a boat, reduce the whale’s swimming efficiency (which adds to Ishmael’s analogy of the whaleship’s fouled hull as compared to the whale’s body). A compelling recent theory is that the hairs in the callosities might even sense the movement of cyamids, which in aquaria studies actually rise up when copepods are nearby. Maybe this helps the whale hosts identify passing schools of plankton?

In a vision similar to Ishmael’s “Brit,” Dr. Bennett in 1840 wrote that “the True-Whale [right whale] of the South . . . has its body encrusted with barnacles and other parasites, often to the extent of resembling a rugged rock.”6 While sailing in the South Atlantic aboard the Clara Bell, Robert Weir wrote in his journal something similar about the invertebrate hitchhikers, although less affectionately than Ishmael:

The right whale is a very dirty mamal compared to others of the same tribe. I have noticed they are covered with small insects very much resembling crabs—about half an inch in diameter. On the end of their nose is a bunch of barnacles about 18 inches wide this the whalemen call his bonnet. And when you see a whale just rising out of water it has the appearance of a rock, the barnacles are enormous—as much as two inches deep—the boys often roast them and eat them the same as oysters.7

Ishmael makes it clear, accurately, that the sperm whale has no callosities and barely any barnacles or any other fouling, likely due to their deep diving. The sperm whale’s smooth skin, aside from the scars of battle, was simply another way to elevate the sperm whale as the new monarch of the seas, with Moby Dick as the clean, unencumbered high emperor.