Ch. 21

WHALE SKELETONS AND FOSSILS

But to a large and thorough sweeping comprehension of him, it behoves me now to unbutton him still further, and untagging the points of his hose, unbuckling his garters, and casting loose the hooks and the eyes of the joints of his innermost bones, set him before you in his ultimatum; that is to say, in his unconditional skeleton.

Ishmael, “A Bower in the Arsacides”

Having already described him in most of his present habitatory and anatomical peculiarities, it now remains to magnify him in an archæological, fossiliferous, and antediluvian point of view.

Ishmael, “The Fossil Whale”

Biding his time until the season-on-the-line as he percolates on the White Whale, Ahab steers the Pequod up through the South China Sea. Ishmael, meanwhile, continues to dissect the whale through the processing and trying out of the blubber. The remaining and deepest duties of this anatomization are to examine the animal’s skeletal system, which leads inevitably to some whale-sized themes that he believes to be worthy of a condor’s quill and a crater full of ink. In these three chapters, “A Bower in the Arsacides,” “Measurement of the Whale Skeleton,” and “The Fossil Whale,” Ishmael engages with comparative anatomy and catastrophism, with the natural theology of the day, and with the pre-Origin of Species understanding of bone, fossil, and man’s place in what nineteenth-century natural philosophers had been learning to be a wide and evermore ancient universe.

WHALE SKELETONS

For nearly fifty years Ewan Fordyce has studied whale bones and fossils. He has spent a good part of his career on his knees brushing dirt off fossilized fragments or with a chainsaw freeing a block of lime from a quarry before the miners obliterate the treasures inside. Primarily from this post in New Zealand, but also with other paleontologists from all over the world, he’s found dozens of extinct species of ancient whales, giant penguins, and a thirty-foot-long proto-white shark. His office, his lab, and the basement storage under the museum that he manages are piled high with specimens, from tiny cases of grain-sized foraminifera to eight-foot-long blocks of stone and dirt on palettes. In his office, lab, museum, and basement are shells, rocks, beaks, and teeth. For comparison purposes, he collects bones of extant species of whales, too, some of which are propped up against storage shelves as casually as you’d lean a broom against a closet.

Every moment of his research over a blink of a half-century has reminded Fordyce of how Homo sapiens represents the briefest of ticks in deep time. I don’t know whether he’s always been this way, but this perspective seems to have honed a nearly hypnotic, kindly calm to him. Occasionally what he says is actually quite biting and even depressing, yet his delivery is so gentle and even that I barely realize its darkness until later.

It starts easily enough. Fordyce thumbs across the pages of his own dusty copy of the novel. “I remember parts of Moby-Dick being really quite exact and revealing,” he says. “But when I reread Melville on the skeleton, I think he didn’t do a very good job. I was waiting to read about the skull of the sperm whale shaped like a Roman chariot, for example, which is a widely used analogy. But instead we’re left groping in the dark trying to understand what he was looking at. He seems to be struggling, really. With anatomy.”1

Fordyce’s point is fair. Ishmael had given some description of the skull and jaw in “The Nut,” but in “Bower in the Arsacides” and “Measurement of the Whale Skeleton,” although Ishmael suggests a quantitative rigor, he is thin on what the skeleton actually looks like. To open his description in this chapter pair, Ishmael explains that he once visited the island of Tranque (a small island off Chile) in the Arsacides (the Solomon Islands, the entirely other side of the Pacific). Here Ishmael visits a skeleton that the Pacific Islanders had reconstructed from a beached sperm whale. This sperm whale skeleton on Tranque, overgrown with ivy, is seventy-two-feet long, he says, twenty feet of which is the skull and jaw. Fordyce corroborates Ishmael’s claim that a sperm whale’s skeleton represents about four-fifths of the animal in life. Ishmael believes then that this whale would have been ninety feet in his skin. Ishmael says the animal would’ve weighed about ninety tons, equivalent to a village of 1,100 people. This is also reasonable if a sperm whale were indeed ever that long.2

When he wrote Moby-Dick, Melville did not have the opportunity to stand on the balcony of Great Mammal Hall at Harvard with Rob Nawojchik, nose to nose with three whale skeletons of three different species. Nor could he examine a range of cetacean fossil bones with the likes of Ewan Fordyce in a museum in New Zealand. At Harvard, it was not until 1865 that Agassiz’s son Alexander organized the acquisition of the museum’s first whale skeleton, a North Atlantic right whale from Cape Cod. The articulation of Harvard’s full sperm whale skeleton, from an animal killed in the Azores, wasn’t completed for display until 1891, the year Melville died. I’m actually fairly certain that before writing Moby-Dick Melville never saw an actual full whale skeleton of any species, in any of his travels, even during his short visit to Paris where he could’ve seen the baleen whale skeleton at Baron Cuvier’s natural history museum, the one that Emerson described in his Boston lecture on natural history in the 1830s.3 (See fig. 38.)

FIG. 38. Baleen whale skeleton at the Museum of Natural History, Paris, by Victor Vincent Adam (c.1830).

In “Bower in the Arsacides” Ishmael explains that he must be truthful in his measurements, because he knows of whale skeletons that exist in museums and curators could call him out on any exaggerations. Ishmael mentions the baleen whale skeletons in Hull and the sperm whale skeleton on the Yorkshire coast, at Burton Constable, which all truly existed and still do. But Melville never traveled to these places. The “Greenland or River Whale” skeleton that Ishmael mentions in Manchester, New Hampshire, he likely plucked verbatim from Thoreau’s A Week on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers (1849). I suspect this was only a beluga or a narwhal skeleton, anyway. So it seems the most of a large whale skeleton that Melville ever saw in person was the skull or lower jaw. He certainly saw illustrations of sperm whale skulls printed in his encyclopedia and perhaps in a scientific journal or two. (See earlier fig. 7.) He also saw line art of full baleen whale skeletons in a couple of his fish documents, but he could not have seen a complete illustration of a full sperm whale skeleton, since no one had published anything like this anywhere before 1851.4

Melville seems to have gotten most of his skeletal information from Surgeon Beale’s detailed descriptions of the skeleton of a sperm whale that beached near the North Sea village of Burton Constable in 1825. Beale described, for example, forty-four vertebrae; Ishmael says “forty and odd” for his skeleton. Beale wrote that the last one is “nearly round, and is about 11/2 inches in diameter”; Ishmael calls his final vertebra two inches in width, “something like a white billiard-ball,” with two still smaller ones lost because the “little cannibal urchins, the priest’s children” stole them to play marbles.5

In 1818 Baron Cuvier purchased in London a large but damaged sperm whale skeleton. This seems to have been unknown even to Beale, who thought the only full sperm whale skeleton in collections was the one in Burton Constable. Ishmael’s suggestion that Sir Constable himself wanted to make money off the sight was probably a poke at P. T. Barnum and others whose natural history displays in America in the 1800s ran parallel and often intersected with the more august collections, such as those being rapidly assembled by Louis Agassiz at Harvard and by the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia. The latter was the first one in America, opening its doors in 1812. The tens of thousands of specimens that had returned from the Wilkes Expedition, and which would later form that early core of the Smithsonian Institution, were largely unattended even by 1851—and the scientifics certainly did not bring back full whale skeletons.6

Part of the problem was what remains true even for Fordyce today: whale skeletons were hard to find, to transport, to put together, and then to manage because of the weeping oil that seeps regularly from the bones for years, making a stink and a mess. Over their entire careers, Agassiz and Barnum were eager for a large whale skeleton of any species. But they never got one. When Dr. Jackson dissected the baby sperm whale that had been brought up to Boston on a railway car in 1842, for the first fully documented dissection of a sperm whale on shore, he had to bring the cartload of organs by horse over to the Medical College at Harvard. This was after he stitched the whale back together, presumably for continued public display by an entrepreneur of some kind.7

It was not until 1851 that a curator and artist named William S. Wall at the Australian Museum in Sydney published a booklet that Melville would’ve loved to have seen as he was finishing up the novel. Wall described what seems to be the first full sperm whale skeleton assembled, which he then illustrated himself (see fig. 39). Wall had read in the newspaper about a roughly thirty-seven-foot whale towed in by a merchant schooner. After convincing the captain that he needed to have the entire whale, including the lower jaw—which the captain wanted as a souvenir—Wall found four former whalemen from Portugal to help him clean up the carcass and tow it to a beach of an island in the harbor. Here he got special permission to store and cover it in a lime mixture. Wall tracked down the tail, which had been cut off with the blubber and brought to market. Two months later, as the skeleton was nearly clean, he found the missing right flipper at a beach on the other side of the harbor, thanks to a report by a couple boys who described a “strange fish” on the rocks. Wall said the smell of the whole process and the preparation of the skeleton was “most offensive to the senses.”8

FIG. 39. An approximately thirty-foot long skeleton of a sperm whale curated and illustrated by William S. Wall at the Australian Museum in Sydney (1851). Wall believed this to be a separate species, which he called Catodon Australis. Note the vestigial hind limb bones (fig. 4), which he cut out of another sperm whale.

The only parts missing from Wall’s skeleton were the vestigial pelvis bones. “The pelvis is hard to find,” Fordyce tells me. “You need to know where to look. They’re long and thin, floating there. About this size.” He found a bone on a shelf and held it up. “They’re a missing link.”

Fortunately, soon after finding his whale, Wall found another sperm whale, this one beached. From this he intrepidly dug out a set of these bones, despite, he says, “some danger from the heavy surf which broke over it.” Although Wall understood at the time that cetaceans had vestigial bones that matched the developed pelvis and “hinder legs of ordinary mammals,” he did not discuss them in his booklet as any kind of meaningful missing link. For his part, Beale simply described the “rudimentary pelvis” without comment as to any evolutionary significance. Agassiz figured that vestigial parts were part of God’s patterning, an affinity with other mammals that He just reduced when making a whale. Ishmael doesn’t say anything about the whale’s vestigial pelvis. Seemingly useless parts, however, was one of the evidences for the transmutation, the fluidity, of species. Darwin would argue a few years later in Origin of Species for evolution by natural selection by, in part, discussing the “rudimentary, atrophied, or aborted organs,” such as the vestigial wings on some insects, “the mammae of male mammals,” and the teeth in fetal baleen whales that then disappear as they grow.9

Back in Sydney, Wall argued that the sperm whale that he articulated was an entirely different species. He created multiple tables with various measurements in comparison to published details of Cuvier’s skeletons and the Burton Constable whale, exacting data that Melville would’ve loved to chide. Wall compiled a table of the length and the circumference of each of the forty-four vertebrae, including the last “globular” one with a length of but three-quarters of an inch.10

Ishmael’s measurements in Moby-Dick are more meaningful to the novel beyond simply satirizing detail-oriented scientists. Ishmael mentions a few times that the skeleton only reveals so much about the whale in life, emphasizing the unknowability of the animal, and thus the sea more broadly, especially to those who spend their lives ashore. This scene of the skeleton in the grove has deep biblical connections, too, including from the Book of Job. God says to Job, when considering the leviathan with smoke coming out of its nostrils: “Canst thou draw out leviathan with a hook? or his tongue with a cord which thou lettest down?” Job’s leviathan cannot be measured in Moby-Dick. The slapstick chiefs, in turn, whacking each other with yardsticks, knock the foolishness all the way across the globe—not just to Pacific Islanders, but to the scientists and priests in America and Europe who argue over the odd inches of truth. Ishmael ends “The Fossil Whale” with American sailors worshipping a whale skeleton in the Mediterranean, being no less reverent or foolish. The “Bower in the Arsacides” scene might even parody the description of a visit by the Wilkes Expedition to a Pacific island that they had named Bowditch Island, after the famous American navigator-mathematician. The expedition’s officers convinced an old priest to allow them into a temple, in and around which the Americans conducted a sort of quantitative anthropology, measuring the height of the idols and the dimensions of the tables upon which their gods sat.11

Ishmael’s measurement of the skeleton, with its comic and spiritual elements, is a prime example of scholar Jennifer Baker’s emphasis on Ishmael’s “honest wonders.” Ishmael aims to impress the reader with the size of the whale. This often requires quantifiable, accurate measurements to convey how extraordinary are the facts on their own, without embellishment. Baker found that in one of Emerson’s lectures in Boston, he explained a sentiment that would be Melville’s approach to depicting nearly all of the natural history in the novel: “The poet loses himself in imaginations and for want of accuracy is a mere fabulist; his instincts unmake themselves and are tedious words. The savant on the other hand losing sight of the end of his inquiries in the perfection of his manipulations becomes an apothecary, a pedant. I fully believe in both, in the poetry and in the dissection.”12

In other words, Ishmael’s epic yarn needs the numbers. He wants to be fact-checked by the curators of the museums. Ishmael wants you to know, however, that these measurements are but one facet. Ishmael, the polymath, is all about your interdisciplinary studies at a time before the bifurcation of the humanities and the sciences or any categories of right or left brain. Ishmael was all about empiricism and Romanticism. Idealism and materialism. Locke and Kant. A tattoo of a poem on his arm beside a tattoo of the measurements of a sperm whale skeleton.

FOSSIL HISTORY OF THE SPERM WHALE

After showing off a floor-to-ceiling cast of the fossilized bones of an extinct baleen whale that is about twenty-six million years old, Fordyce (sneezes) walks me over to one of his prized finds. This is behind glass: a “shark-toothed dolphin” skull that is over twenty-four million years old. It has triangular, serrated teeth rather than the more conical teeth of toothed whales today. This shark-toothed dolphin might have echolocated and perhaps fed on the giant penguins of its epoch.

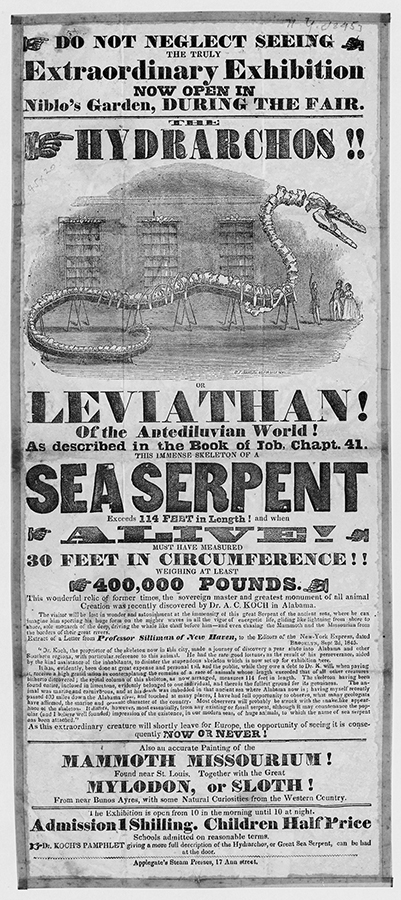

This shark-toothed dolphin skull also looks to me like the head of a massive crocodile. Or even the skull of the basilosaurus that Ishmael describes in “The Fossil Whale.” Fordyce says that Ishmael’s was a true story, one that actually helps explain why this shark-toothed dolphin skull in front of us is not a reptile. In 1839 an American physician named Richard Harlan brought to London some fossilized fragments from a specimen in Alabama that he believed to be a giant reptile. He had named it basilosaurus, which means “king of the reptiles.” Fordyce says, “Harlan was widely interpreted as a bit useless, but he would have been struggling with what resources he had at the time.” Harlan packed the teeth, perhaps rolled in flannel, and brought them across the Atlantic to London where at the Royal College of Surgeons Richard Owen (“who was really quite brilliant,” Fordyce says) examined the remains of this basilosaurus specimen. Owen noticed that the teeth were worn down. Reptile and shark teeth have evolved to fall out, while these fossilized teeth had two distinct roots to anchor it into sockets in the jaw, like mammals. Owen proposed to change the name to Zeuglodon, which means “yoked tooth.” This name did not stick, and scientists today recognize the first naming, however inappropriate. A few years after Owen’s identification that it was actually an early whale—one of the first fully aquatic cetaceans, it turns out—a fossiliferous collector named Albert Koch collected enough basilosaurus fossils to build, with perhaps other bones and a few rocks, his own extinct “sea serpent.” Spurring international debate as to its veracity, involving the likes of Richard Owen and Charles Lyell, Koch took his skeleton creation to New York City in 1845, then to Boston and abroad, exhibiting it as “Hydrarchos” and playing off the Leviathan in Job that lived before the time of Noah’s flood.13 (See fig. 40.)

FIG. 40. Broadside for Albert Koch’s New York City exhibit of the (inaccurately) articulated fossil bones of Basilosaurus sp. (1845).

In Melville’s day, fossils and the recognition of extinction did much to shake the Western world. Baron Cuvier presided as the authority over these sciences in the 1820s. Richard Owen did so in London in the 1830s and ’40s. Louis Agassiz carried this torch in America. In 1842 Owen famously coined the very name “dinosaur.” Discoveries of this kind stretched the notion of Genesis and God’s creation of a perfect world. Fordyce explains that it was geology and paleontology that forced the shifting of paradigms. These were the most public sciences of the day and the most staggering to natural theologians, which included Owen and Agassiz. The three-volume work by Scottish geologist Charles Lyell, Principles of Geology (1830–33), for example, not only was profound scientifically, but also was a huge popular hit read by a wide range of audiences. One of Lyell’s major points was that the Earth was far older than previously recognized. The Earth was constantly, very slowly rising, subsiding, changing in the same ways that could be observed today—sedimentation, erosion, a small earthquake here, a little eruption there—slowly, incrementally, changing the Earth over millions and millions of years. Melville was among those readers of Lyell, or at least other texts that summarized current geology and paleontology. In his novels before Moby-Dick, Melville engaged, with a layman’s understanding and often with humor, not only with the theories of coral reef and atoll formation, but also with interpretations of the layers of earth deposits and fossil discoveries. For part of the basilosaurus story, for example, Melville stole outright a bit of poetry from Owen’s scientific paper on the topic (which Melville likely read in his encyclopedia). Ishmael’s wild, lovely proto-Darwinian closing line about the mutations of the globe getting blotted out of existence is almost verbatim from the closing words of Owen’s paper.14

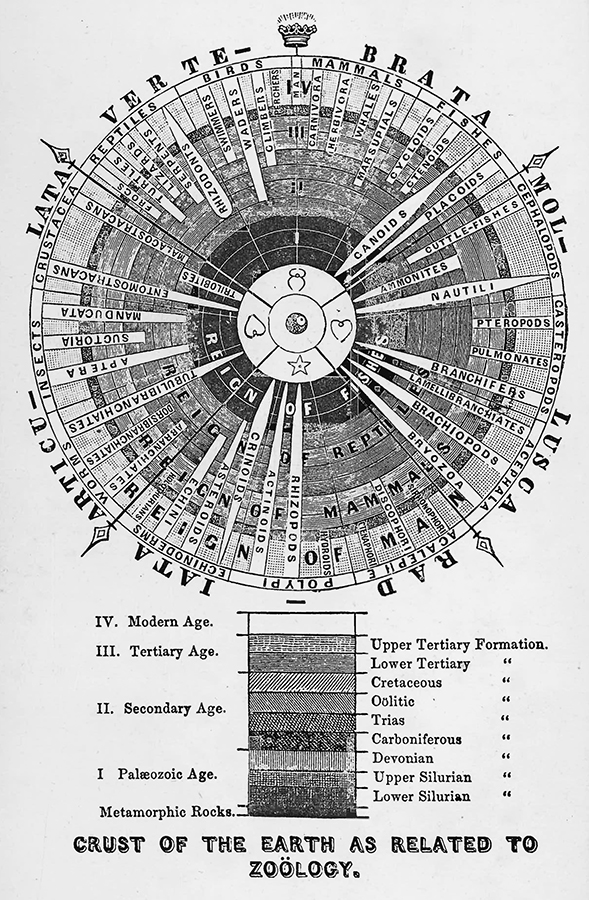

Though Ishmael ends Moby-Dick with a biblical reference to the Earth at 5,000 years at the Flood, in other parts of the novel, such as in “The Fountain,” he recognizes our planet as on the order of “millions of ages” old before Noah built the ark. Louis Agassiz and others in the 1840s organized the fossilized ages into primary, secondary, and tertiary periods. Lyell divided these still further. In “The Fossil Whale” Ishmael relays what he might have learned through Agassiz, that extinct whales, even basilosaurus, appeared only in the tertiary fossil layers. This has proven true. In the nineteenth century naturalists dated the rocks by relative age, looking at the layers of rock and the fossils preserved within, which they then compared to the sedimentation rates that they could observe in the present day. Agassiz, from his natural-theological desk, organized the historical layers of the Earth while retaining the supremacy of man as king, as God’s chosen species. (See fig. 41.)

FIG. 41. The frontispiece of Agassiz and Gould’s Principles of Zoology (1851). Note how “man” sits at the top with a crown, within the Modern Age, the “Reign of Man.”

While sailing aboard the Beagle, Darwin grew particularly inspired by Lyell’s work on geologic processes and fossils. He became far more interested in how atolls formed and why he found shells in the hills of the Andes than he was about finches or the causes of bioluminescence. Darwin was regularly seasick during his passages aboard the Beagle. So he spent any time he could ashore “geologizing.” In “The Fossil Whale” Ishmael allows himself to also be swept away with the cosmic significance of the new understanding of the breadth and age of the Earth and the universe, while still swirling this into his masthead natural theology:

When I stand among these mighty Leviathan skeletons, skulls, tusks, jaws, ribs, and vertebræ, all characterized by partial resemblances to the existing breeds of sea-monsters; but at the same time bearing on the other hand similar affinities to the annihilated antechronical Leviathans, their incalculable seniors; I am, by a flood, borne back to that wondrous period, ere time itself can be said to have begun; for time began with man. Here Saturn’s grey chaos rolls over me, and I obtain dim, shuddering glimpses into those Polar eternities; when wedged bastions of ice pressed hard upon what are now the Tropics; and in all the 25,000 miles of this world’s circumference, not an inhabitable hand’s breath of land was visible. Then the whole world was the whale’s; and, king of creation, he left his wake along the present lines of the Andes and the Himmalehs. Who can show a pedigree like Leviathan? Ahab’s harpoon had shed older blood than the Pharaohs’.15

Ishmael stretches the geographic extent of the ice age, and he describes more of an Agassizian catastrophism. Yet Fordyce says: “I thought Melville was good there. The Himalayas are uplifted marine rocks, and those contain rocks from Eocene times and the first transitional whales, such as the pakicetids. So Melville was spot on. Where there were now mountain ranges, there were once whales. It doesn’t work for the Andes. The Andes are volcanic rock. They’re erupted. Whereas the Himalayas are sedimentary rock, they’re uplifted from the sea. But I thought that Melville was really good there.”16

In closing, I ask Fordyce what he thinks of the new name so many are using for this epoch, the Anthropocene. Fordyce says without the faintest shift in tone or calm: “Shocking. True. I’m a paleontologist, so I deal with the impotence of past life, and almost everything I deal with is extinct—so to me extinction is a natural process. It’s the fate of all species. Most of them are going to go extinct without leaving descendants, and a few are going to leave descendants. Their lineage alone persists. So it is a natural cycle of doom. Then the next question is: should people be accelerating this? Well, I don’t think so at all. And I see no hope either. I think it’s truly hopeless. You just have to read Darwin and Wallace’s paper of 1858 and you realize that they’re talking about the struggle of nature, the balance of nature. There is always an excess of young produced. And the numbers in populations never rise because the Earth is saturated. And our species is saturating it furiously. I’m deeply pessimistic.”

In Moby-Dick these three scenes on whale skeletons and fossils do not seem to plunge Ishmael into a state of helplessness, but instead into a state of wonder in the smallness and insignificance of the human race. Ishmael lives on an ocean that seemed ferocious and beyond the fingerprint of humanity. Yet he was clearly rattled by the new notions of deep time and how this might displace God as the ultimate singular designer and creator. These anxieties and ponderings play out in Ishmael’s musings and Ahab’s rages.

Put another way, a century later in 1945, which was still before the confirmation that whales definitively evolved from land mammals and even before the recognition of plate tectonics, scholar Elizabeth Foster wrote about the effect of developments in geology on our author’s psyche: “At some time between Typee and Moby-Dick, Melville’s universe changed: the benevolent hand of a Father disappeared from the tiller of the world.”17