Ch. 22

DOES THE WHALE DIMINISH?

The moot point is, whether Leviathan can long endure so wide a chase, and so remorseless a havoc; whether he must not at last be exterminated from the waters, and the last whale, like the last man, smoke his last pipe, and then himself evaporate in the final puff.

Ishmael, “Does the Whale Diminish?”

As the Pequod continues northeasterly toward the open Pacific, ever searching for the first glimpse of the White Whale, Ishmael spins his final essay on the natural history of ocean life. “Does the Whale Diminish?” is a punctuation mark to finish the dissection and anatomization of the whale as an animal. By the end of this chapter Ishmael puts to rest all his factual elements about the process of whaling and its significance, and all the information about the natural history of the sperm whale and its fellow ocean inhabitants, all that he feels he needs as background and scaffold before entering into his final act of the drama.

In “Does the Whale’s Magnitude Diminish?—Will He Perish?,” the full name at the start of the chapter, Ishmael confronts human effects on whaling populations. He answers these two questions by concluding: no, the magnitude of whales has not diminished over the centuries—whales are actually at their largest in his present day; and no, whales will not go extinct—although hunting has cut their numbers and influenced their behavior.

DOES THE WHALE’S MAGNITUDE DIMINISH?

In “Does the Whale Diminish?” Ishmael lists the Zeuglodon fossil skeleton found in Alabama as measuring less than seventy feet. He believes this to be the longest known whalelike fossil found on record at the time. This seems true. Ishmael explains that the “ancient naturalists” of Greece, such as Pliny and Aldrovandus, were comically incorrect in their claims that whales were acres wide and eight hundred feet long. Ishmael continues that even in his present day the accounts of sober naturalists greatly exaggerate due to misinformation and lack of experience firsthand. For example, he says, French naturalist Lacépède lists the right whale as three hundred twenty-eight feet long.1

Ishmael is correct that most of the historical measurements of whale length and girth were far overestimated. Similar to his treatment of stories about the giant squid, Ishmael tolerates no absurd historical exaggerations, yet he permits himself a smaller stretch in the tradition of a sailor’s yarn. So “on whalemen’s authority” Ishmael declares that sperm whales can reach one hundred feet long from head to flukes. He never states the actual length of the White Whale himself, only writing of its “unwonted magnitude,” which leaves the rest to the reader’s imagination—within, er, reasonable parameters. None of Melville’s fish documents claim the sighting of a sperm whale of one hundred feet. Nor have I found any similar record, other than the dubious secondhand claim that in 1859 a Swedish whaleman captured a 110-foot-long Mocha Dick. Owen Chase estimated that the whale that sank the Essex was eighty-five feet long. Surgeon Beale, by presumably measuring the half-sunk dead whale alongside against the length of the ship’s deck—if not sending a Queequeg-like harpooner down with a tape measure—recorded an eighty-four-foot sperm whale. The Nantucket Whaling Museum has an eighteen-foot-long sperm whale jaw, which experts believe might, by proportion, match that of a whale of eighty feet. In 1874 whaleman-author William Davis claimed that he once measured a seventy-nine-foot sperm whale, and Davis heard from another captain that they had caught a sperm whale off New Zealand that was ninety feet long, with a jaw that was eighteen feet. In 1895 the whaleship Desdemona captured a whale that they measured at over ninety feet. The New Bedford Whaling Museum has two of this whale’s teeth, the largest ever brought home, which are at 113/4″ long. The men would’ve wrenched these teeth out of the whale’s jaw by lashing it on deck.2 (See fig. 42.)

FIG. 42. Francis Allyn Olmsted’s illustration, “Pulling Teeth,” from a large sperm whale’s jaw (1841).

Today, sperm whale experts are skeptical of even Beale’s eighty-four-footer (as was Dr. Bennett at the time). Marine biologist Randall Reeves estimates that the maximum size of male sperm whales is about sixty feet, which still weighs some 120,000 pounds. Sperm whales are the most sexually dimorphic of any whale. Female sperm whales average less than thirty-six feet and weigh less than half of the largest males.3

Ishmael’s logic is suspect when he compares the size of current animals to those of historical populations by using old illustrations and other ancient references. I read Ishmael as tongue-in-cheek here. Though he believed the gist of the matter, I don’t think he really bought into his own pseudoscientific comparisons any more than he peddled in phrenology. Making Moby Dick the largest sperm whale and thus the largest predator that has ever lived serves his yarn and elevates still more his white monster.

In these comic comparisons, Ishmael also continually elevates sailor knowledge and experience above the naturalists ashore, making fun of scientific discourse. He places whales, cattle, and humans all on the same plane, thinking about them all as animal species responding to environmental factors. Literary scholar Elizabeth Schultz argued that this equalization was more revolutionary than it might seem to the twenty-first-century reader. Melville created in the novel a “cetacean-human kinship” that was ahead of his time, encouraging a sympathy for the whale.4

Although twenty-first-century biologists agree with Ishmael that whales over previous centuries were not three times larger than they were in the 1850s, a team of researchers from universities in Zurich and Tasmania recently looked at historical data that recorded whale length and found some controversial trends that potentially turn Ishmael’s question about the diminishment of the whale’s magnitude on its head, and perhaps temper our skepticism of enormous sperm whales reported by nineteenth-century whalemen. The researchers, led by Christopher Clements, looked at the data collected by the IWC of the reported kills from 1900 until 1986, which was when the international moratorium on the hunting of large whales went into effect. During this time whale populations showed a reduction in their average length when stressed by hunting. The case of the sperm whales was most dramatic. Their average length decreased from the start and just kept decreasing until whales killed in the 1980s measured on average 13.1 feet shorter than those killed in 1905, an over twenty percent reduction in average length! Perhaps this was simply due to hunters selectively killing the largest whales available and moving down, but the researchers claim that with sperm whales they can look back at the data and see warning signs that the sperm whale population was nearing a tipping point of overexploitation, even forty years before, four generations of whales.5

Could it be then, unknown to Melville and his contemporaries, that the average sperm whale’s magnitude had already been diminishing by the peak of American open boat whaling in the 1840s, a hunt that had begun impacting sperm whales since the 1700s?

WILL HE PERISH?

Ishmael recognizes that the topic of the potential extinction of whales at the harpoons of human hunting has been of some debate in the 1840s, especially in consideration of the number of mast-headers searching the globe “into the remotest secret drawers and lockers of the world.”6

Ishmael begins the discussion by comparing the whale’s fate to the pending extinction of the buffalo. He recognizes that “the cause of [the buffalo’s] wondrous extermination was the spear of man,” but compares the situation to the inefficiency of American whaling. In comparison to men killing forty thousand buffalo in four years, he says, American whaleships on a four-year voyage were content with some forty whales. Ishmael chooses his numbers for poetry, but they are accurate, at least in terms of whaling: a typical successful whaling voyage in the 1840s would capture approximately thirty to sixty whales—and kill or injure several more that they were unable to collect and bring back to the ship. The totals of whales killed for a given voyage were greatly dependent on how many barrels of oil each whale yielded. Catching one or two whales a month on average was considered a successful trip. Ishmael does admit, however, that it was getting harder to find whales—the ships have had to sail farther and farther—and that he believes the hunting by whaleships around the world has actually altered sperm whale behavior.7

The right whales, in particular, he says accurately, were not as commonly found in their previously known regions. Regardless, Ishmael does not believe the right whale population is in danger. He says of right whales (which included bowheads as he knew them):

For they are only being driven from promontory to cape; and if one coast is no longer enlivened with their jets, then, be sure, some other and remoter strand has been very recently startled by the unfamiliar spectacle.

Furthermore: concerning these last mentioned Leviathans, they have two firm fortresses, which, in all human probability, will for ever remain impregnable. And as upon the invasion of their valleys, the frosty Swiss have retreated to their mountains; so, hunted from the savannas and glades of the middle seas, the whale-bone whales can at last resort to their Polar citadels, and diving under the ultimate glassy barriers and walls there, come up among icy fields and floes; and in a charmed circle of everlasting December, bid defiance to all pursuit from man.8

Though Ishmael says that American hunters have taken far more right whales—fifty to one compared to sperm whales—the right whales, he says, are much like elephants in that they can survive the loss of enormous numbers, especially because the whales have such vast “pasture” in which to dwell. Whales, like elephants, Ishmael says, have such long lifespans that it extends their species’ survival. Thus Ishmael concludes confidently: “In Noah’s flood he despised Noah’s ark; and if ever the world is to be again flooded, like the Netherlands, to kill off its rats, then the eternal whale will still survive, and rearing upon the topmost crest of the equatorial flood, spout his frothed defiance to the skies.”9

From a maritime history perspective, Ishmael’s position on the sustainability of whale populations is unremarkable, even reasonable. The nineteenth-century whalemen had observed that they were depleting whales in various regions as they sailed farther and farther from New England to catch whales. This often happened quickly. For example, within the two decades of the 1830s and ’40s, the whalemen hunted so many thousands of right whales off the coast off New Zealand that they crashed the local population by an estimated 90 percent. The whalemen then moved up into the North Pacific. Within the decade of the 1840s, which Ishmael recounts as an example of abundance without yet seeing the other end, the men killed tens of thousands of right whales so quickly that this region too was abandoned to go still farther north for bowheads. A whaleman in 1845, whose opinion Melville read in his fish documents, recognized the suddenly poor catches and wrote that “the poor whale is doomed to utter extermination, or at least, so near to it that too few will remain to tempt the cupidity of man.” This whaleman, Mr. M. E. Bowles, predicted the global whale industry, for any species, would be abandoned within a century. Right whales, like Steller’s sea cows, were coastal and slow enough to be more easily caught by open boat whalemen. Right whales were, essentially, sequentially extirpated in a clear, traceable pattern from the North Atlantic around South America and South Africa into the Pacific. Melville and his contemporaries had not yet seen the widespread developments of a long-range explosive harpoon or the twentieth-century technologies that enabled whaling of all species in polar seas with massive diesel-powered engines and wire winches that reeled full-sized whales onto the deck of a steel-hulled ship so the carcasses could be flensed and processed by a few men as it motored off to kill more whales.10

Although human hunting might have reduced the global sperm whale population by about thirty percent in the nineteenth century, sperm whale global health seems to have been less affected than that of right whales. It might be simply that since the sperm whale’s range is so much larger and farther offshore that their contact with humans was reduced. Melville’s idea that sperm and right whales were swimming away and joining together in larger schools, to avoid the ships and harpoons, was also the perception of at least some American whalemen at the time. It made sense. The hunters depended on this idea to justify the reduction of the whales that they saw and could catch. But it wasn’t simply that men were scaring the whales away. They were systematically depleting local populations of sperm whales, too.11

Much of Ishmael’s logic on this question of extinction, despite his attempts at scientific reasoning, are suspect when viewed in hindsight, due, I think, more to misunderstanding than humor. Today, when biologists talk about the survivability of species, the focus is not just on predation, but about reproductive fitness—ideas that Darwin advanced a few years after Moby-Dick, although Ishmael does explain that the gestation period of a mother sperm whale was about nine months (it’s actually probably closer to between fourteen and sixteen months). Ishmael does not talk, as a conservation biologist would today, about fecundity or even food availability. Melville and his contemporaries did not know that while a female sperm whale might indeed live to eighty years or older, she gives birth to only one calf every four to six years, and this rate decreases as she gets older, until she probably no longer gives birth at all.12

In “Does the Whale Diminish?” Ishmael believes that whales probably attain “the age of a century and more.” This fits poetically, building Schultz’s cetacean-human kinship, or a “fraternal congenerity” as scholar Robert Zoellner put it. This longevity is actually not outrageous or beyond the thinking then or today. Right whales, of either gender, live at least to sixty or seventy. Earlier, in “The Pequod meets the Virgin,” Ishmael tells of an extraordinary find in an old sperm whale that they harpooned: “A lance-head of stone being found in him, not far from the buried iron, the flesh perfectly firm about it. Who had darted that stone lance? And when? It might have been darted by some Nor’ West Indian long before America was discovered.” In recent decades the scientists and local Inupiat in sub-Arctic Alaska have found a few old harpoon tips of stone and iron buried in the blubber of captured bowheads. Researchers who have dated these harpoons, along with studying the amino acids in the animal’s eyes, believe that bowheads indeed live to well over one hundred, and even, just maybe, over two hundred years. Melville was surely aware that if there is any trait in animals, or even trees, that creates respect and reverence for our fellow organisms on Earth, it is age.13

Now, the most significant point that Ishmael avoids in regard to extinction and depletion, which is more understood today, is that sperm whales had nearly no predation threats for millions of years before humans were able to enter their habitat. Sperm whales evolved long life spans, social groups, long-term raising of single offspring, big brains, large size, and deep-diving abilities to thrive in a very specific niche in the ocean. Orcas, as a pack, can occasionally take a large whale, but biologists do not believe they have any global effect on their populations. If you remove human hunting and return to the era when Ahab first sailed into the Pacific on his first voyage, the era of the late 1790s and the voyage of James Colnett and the publication of “The Ancient Mariner,” sperm whale populations in the Pacific were limited almost entirely, if not completely, by fluctuations in their food source and competition within their species.

ISHMAEL AND AMERICAN ECO-GUILT

The notion that an animal or plant could go extinct was in the mainstream consciousness in Melville’s time. Species extinction, however, was usually folded by naturalists such as Louis Agassiz into terms that taught that God chose to eradicate certain animals from the Earth with floods and ice ages as part of the progress toward the creation of Adam and Eve. Extinction was part of God’s design. This perception potentially absolved humans of responsibility, because even much of the general public understood by the 1850s that human action, such as hunting, destruction of wild habitat, and general human occupation had threatened local animal and plant-life.14

As early as 1833 an author in the American Journal of Science and Arts concluded his essay on the global fur trade in this way:

The advanced state of geographical science shows that no new countries remain to be explored. In North America, the animals are slowly decreasing from the persevering efforts and the indiscriminate slaughter practised by the hunters, and by the appropriation to the uses of man of those forests and rivers which have afforded them food and protection. They recede with the aborigines, before the tide of civilization, but a diminished supply will remain in the mountains, and uncultivated tracts of this and other countries, if the avidity of the hunter can be restrained within proper limitations.15

This passage was reprinted and paraphrased in multiple other publications, in addition to being read in the halls of Congress. In 1856 Thoreau lamented the loss of large mammals in Concord, Massachusetts—the bear, deer, wolf, lynx, and beaver—due to hunting for food and to protect livestock. In “The Cabin Table” in Moby-Dick, Ahab “lived in the world, as the last of the Grisly Bears lived in settled Missouri.”16

Later in “Does the Whale Diminish?” Ishmael singles out the precarious thinning of buffalo herds because this was on the mind of his contemporaries in America. In his The California and Oregon Trail, Parkman observed that the herds of buffalo had moved westward, and though he witnessed them in astounding abundance, he knew the expansion of new Americans on their way to Oregon and California would exterminate the buffalo as well as the nomadic, indigenous people that depended on them. In 1849 Parkman does not use if, but “When the buffalo are extinct.”17

Though Melville saw the fragility of animal populations on land, he thought those of the sea were different. He represented through Ishmael the views of the experts he wanted to trust on this point, such as Surgeon Beale, who at sea in the 1830s sailed in the new and prolific sperm whale fishery off Japan. Beale believed in a sustainability of whaling that Ishmael echoed almost exactly. “Such is the boundless space of ocean throughout which it exists,” Beale wrote, “that the whales scarcely appear to be reduced in number. But they are much more difficult to get near than they were some years back, on account of the frequent harassing they have met with from boats and ships.” Beale believed the sperm whales were simply becoming more cautious, with an “instinctive cunning” to avoid humans.18

Others observers, such as the merchant Charles W. Morgan in a speech to the New Bedford Lyceum in 1830, explained that one would think the sperm whales would be in danger and “this destruction must eventuate in their extermination,” particularly in considering the whale only has one offspring and they hadn’t ever had enemies before man. But Morgan contradicted this, declaring the greater danger was actually “an oversupply.” Then, in a revision of the speech only seven years later, Morgan acknowledged that the voyages were taking longer and “a full ship being now the same exception to a general rule.”

In 1841 Charles Wilkes reported after returning from his circumnavigation some concern about whale populations. In his “Currents and Whaling” chapter, the one that Melville incorporated carefully into “The Chart,” Wilkes wrote that there is “ample room for a vast fleet” in the Pacific, with space for more ships, but “an opinion has indeed gained ground within a few years that the whales are diminishing in numbers; but this surmise, as far as I have learned from the numerous inquiries, does not appear well founded.” Ishmael says this idea has been put forth by “recondite Nantucketers,” to give it gravitas relevant to the novel, but he closely follows the path of Wilkes’s rhetorical arguments.19

Thus, Ishmael’s belief that whales can survive the pressure of American hunting in the 1850s reflected the mainstream knowledge of his day. At this point in the novel, as Melville builds up to Ahab’s battle, he couldn’t possibly show any vulnerability or potential extinction of whales or show his whalemen heroes as careless to their profession’s future harvest. Ishmael’s arguments, especially from our perspective today, are “wishful, if not desperate, thinking,” according to scholar Elizabeth Schultz. With his recognition of the impending loss of buffalo, with the novel ending the way it does, with his faith in man shaken, Melville’s depiction of whales as even potentially vulnerable reveals his concerns about the sustainability of humanity’s industrial drive.20

Consider this: what did Ishmael have to feel suicidal about in “Loomings” at the start of the novel? Why was he walking and brooding along the streets and docks of southern Manhattan wanting to turn a pistol and ball to his head? What was it really about the sea for Ishmael that was cure? He asks, “Are the green fields gone?” Later in “The Grand Armada” he says that even the islands of Indonesia are unsafe from “the all-grasping western world.” Even in the farthest reaches of the Pacific islands, Melville and his protagonist were aware of man’s heavy hand in habitat destruction and overhunting. Ishmael chooses not to travel west from New York City to cure his urban ills. He goes to sea.21

Melville and his contemporaries did not know of too many full extinctions at sea, other than, for example, the Steller’s sea cow and the spectacled cormorant up in the far Aleutians or the loss of the great auk in the Canadian Maritimes. But American mariners certainly knew that their coast looked different in 1851 than it had in 1651. They knew this was a result of overfishing and overhunting. The Caribbean monk seal was a rare sighting by 1851—they would be extinct by the mid-twentieth century. Atlantic salmon were in steep decline, locally eradicated in places, due to the damning of rivers and overfishing with weirs. Hunters extirpated North Atlantic right whales from the waters of New England by the mid-1700s, due to shore-based hunting and a long history of whaling in the Gulf of Maine, which might’ve begun as early as the 1500s. The North Atlantic population of the gray whale was already mysteriously extinct or nearly so before seemingly any European or even Native American hunting. In 1839 an entry in the popular The Naturalist’s Library lamented the wasteful, selfish destruction of the entire population of fur seals in the South Shetland Islands in only two years, over 320,000 animals.22

In 2015 a research team led by Douglas McCauley looked at global extinctions at sea in comparison to those on land. They found that our effect on species in the marine environment has been thousands of years slower than in terrestrial environments. Although the rate of extinction in the ocean is far less—at least as far as we can tell—we have had our effect over the past couple hundred years. And a tipping point might be ahead. McCauley’s group found that humans have “profoundly” decreased the abundance of large whales and smaller marine fauna (see plate 8). Considering threats of climate change, mismanagement, and habitat loss in the coming decades, McCauley and his colleagues concluded: “Today’s low rates of marine extinction may be the prelude to a major extinction pulse, similar to that observed on land during the industrial revolution, as the footprint of human ocean use widens.” They looked at factors such as global warming, increased shipping traffic, increased dead zones, and the increasing mining of the ocean floor. Animals at sea certainly have more wild space to roam and potentially can respond more naturally to global warming and ocean acidification, but they too can be overwhelmed. Ishmael’s “polar citadels,” which he believed would harbor whales, are now melting and opening up lanes for shipping traffic, new areas for fishing, and further and farther all-grasping.23

Perhaps we’ve underestimated the psychological and sociological effects of the Industrial Revolution on those that were in its earlier gears. Just as so many of us do today, Melville, Thoreau, and others of their generation also felt socially and individually guilty about human impact on the natural world—even if this helplessness might have been tempered or rationalized in a larger perception of God’s role in the natural order and what Americans had begun to term manifest destiny. Is the foul, choking, smoking scene of “The Try-Works,” in which the whalemen are “burning a corpse,” an indictment of Ishmael’s industrial age? Tortured Ahab sees his mind and fate on railroad tracks. Melville is fully aware, and seemingly more sympathetic than most, of the soil on which he stands—on which still waged the systematic genocide of Native Americans. Melville saw firsthand the foul impacts of Western man on Polynesian cultures in the South Pacific. He read of it happening in the American West. Did Ishmael hope that he could escape back out to sea, to get away from all of these visions, back to the true “pre-adamite” wild, a pure ocean beyond the touch of man?24

If Ishmael begins to recognize that whales are endangered by hunting, if these endless reefs are no longer pristine, this might be just too all-crippling, just too Pip-like maddening—right?

WHALE POPULATIONS TODAY

Although it’s nearly impossible to calculate how many whales early Native Americans, Indonesians, Japanese, and Europeans killed when they first starting pushing off their coasts in order to harpoon or net coastal marine mammals, recent scientists, such as Tim Smith and his colleagues of the World Whaling History Project, have worked with a variety of source material, including Maury’s logbooks, as well as a range of sampling methods and statistical models to get a sense of how many whales there were before Melville’s day.

In comparison to nineteenth-century whaling under sail from small boats, modern twentieth-century industrial whaling was far more devastating to whales, especially the large rorquals. The open boat killing of sperm whales peaked in the late 1830s at about five thousand sperm whales a year. The discovery of petroleum in 1859 and the Civil War greatly diminished the open boat whaling fleet around the world, but then sperm whale kills began to rise again in the mid-1920s, unrelated to, although poetically beside, the last voyage of the Charles W. Morgan and the wreck outside New Bedford of the last working American whaleship, the Wanderer, in 1922. Twentieth-century whalemen, capable of capturing the large and fast rorquals, found new markets for whale products. Several large nations, including the US, killed and used whales for farm animal feed and for other products such as margarine, soap, bone meal, and cosmetics. Baleen was nearly useless, replaced by light metals and then plastics, but spermaceti oil continued to have a market as a high-grade lubricant as well as in a range of products such as inks, detergents, cosmetics, and hydraulic fluids. The Japanese and Norwegians also caught whales for human food. The modern hunt of sperm whales peaked in the mid-1960s, with a global catch by all nations of close to 22,000 sperm whales killed per year. And many of the modern industrial hunters turned to sperm whales only after the blue, sei, and fin whales proved harder to find.25

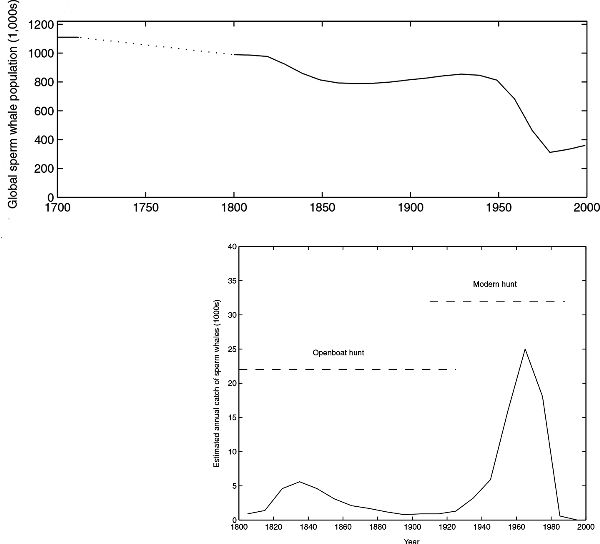

Hal Whitehead has overlaid the numbers of sperm whales killed by commercial hunting against his best possible estimates and modeling of sperm whale global populations (see fig. 43). He cautiously suggested that about 1.1 million sperm whales swam the global ocean before the start of the 1700s, before Nantucket whalemen began capturing them regularly off New England. By the publication of Moby-Dick, there were perhaps some 800,000 sperm whales left, and then, at the nadir, down to about 300,000 sperm whales anywhere in all oceans. Whitehead believes that the moratorium in the 1980s came just in time—before a full crash of the global sperm whale population. No one has been able to conduct a systematic, reliable global population count of sperm whales since then, but as of 2018 the IUCN lists sperm whales tentatively as “vulnerable.”26

FIG. 43. Estimated global sperm whale population, 1700–1999 (above), and estimated sperm whales captured and killed by hunting, 1800–1999 (Whitehead, 2003). The lower figure does not account for the significant numbers of sperm whales killed or injured that whalemen were unable to bring back to the ship to process. The upper figure, however, does incorporate estimates of those “stuck but lost.”

Ishmael suggests in “Does the Whale Diminish?” that sperm whales are aggregating into large armies for protection. This might not have been as absurd as it sounds. Modern biologists have found that sperm whales in the Atlantic rarely join their matriarchal units together, swimming as ten to twelve females and offspring, while those in the Pacific almost always join units, forming clans of about twenty or thirty individuals. Observers from Captain James Cook to Frederick Bennett to Hal Whitehead have observed scenes of thousands of whales together in transit. It’s not out of the realm of possibility that these clans would ally together, especially if the mothers of these units are killed, but the evidence is not strong enough that human hunting under sail adjusted sperm whale behavior in this way. Whitehead and Rendell believe the large Pacific clans of sperm whales might aggregate to help each other to defend against killer whales.27

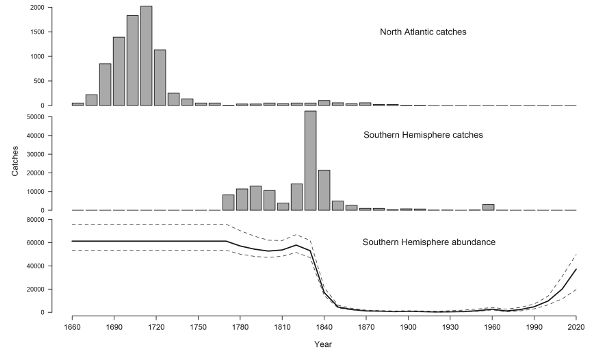

For the right whales, estimating global populations and historic hunting pressure has overlapping but different sets of complexities. Right whales seem less equipped to survive human predation. The number of North Atlantic right whales killed probably reached its peak a century earlier at over 2,000 animals for the decade between 1710 and 1720. By the mid-1700s whalemen barely found and harpooned any right whales at all along the North American coast.28 (See fig. 44.)

FIG. 44. Based on historical logbooks and other data, the capture of North Atlantic right whales peaked in the early 1700s (top, Laist, 2017), while the captures of southern right whales peaked in the 1830s (middle, IWC, 2001). Note the difference in scale: how many more southern right whales were killed throughout the Southern Hemisphere, but catches for both areas are greatly underestimated due to loss of records. Below is the estimated trajectory of abundance of southern right whales based on mtDNA research from current whales (Jackson, et al., 2008). Researchers have not yet been able to do this abundance modeling with the right whales of the Northern Hemisphere, but both species never recovered and are in imminent danger of extinction.

Over the course of the Charles W. Morgan’s thirty-seven whaling voyages from 1841–1921, the longest run of any whaleship in history, the men killed very few North Atlantic right whales, if any—ever. This species is today the most critically endangered of the large whales. In Moby-Dick Melville did not have the men of the Pequod lower their boats to try to catch whales until the South Atlantic. This was historically accurate. In 1849 Captain McKenzie wrote to Maury that for his whole career he “never did—nor ever expected to find right whales on the out ward passage till I reached Lattd 30.˚ South.” On the first voyage of the Charles W. Morgan, the men did not see a whale until forty days into the voyage when they attempted to harpoon a pilot whale just north of the equator, off what is now Liberia. A month later they spotted a couple southern right whales off El Rio de la Plata. Then, on the other side of Cape Horn they finally caught a small female sperm whale. The Commodore Morris, leaving Woods Hole in the summer of 1845, did much better, spotting near the Azores two pods of sperm whales less than three weeks into the trip, capturing one large one. By the time they were at Cape Horn, they’d seen sperm whales, pilot whales, humpbacks, and finbacks, but, no kills and no sightings of right whales of either species. They weren’t wasting time, anyway, as they were now bound for the Pacific where the chances were far better.29

Right whale expert David Laist believes that pre-hunting populations of North Atlantic right whales might have been ten to twenty thousand individuals. Likely because of long, sustained early hunting by man and now primarily because of ship strikes, entanglements with fishing gear, stress from ocean noise, and shifts in copepod abundance with climate change, the North Atlantic right whale is now the lone critically endangered species of large whale. A recent analysis in 2015 found that only 458 individuals of North Atlantic right whales remain on Earth. And any slow recovery seems to have been reversed, judging from recent deaths and lack of births. For the southern right whales, the pre-hunting historical abundance was likely anywhere from 55,000 to over 100,000 individuals, with open-boat whaling beginning in earnest in the late 1700s when whalemen began to travel down to the South Atlantic and then into the Indian Ocean and the Pacific. The southern right whale population across the entire hemisphere is now probably over 25,000 individuals, and is on the rise from a low in the 1920s of only three hundred or so, at the brink of extinction. The North Pacific right whales, which Melville never hunted but which are the animals Ishmael mentions as being killed by the thousands in the “north-west,” the Gulf of Alaska, are now as precariously endangered as the North Atlantic right whales, although very little is known as to their true numbers.30

THOREAU’S OCEAN: THE SAME AS AHAB’S, ISHMAEL’S, AND NOAH’S

In October 1849 Thoreau began a series of trips to Cape Cod, that thin strip of land that embraces Massachusetts and Cape Cod Bays and points out to the Gulf of Maine. Today this is, and likely has been for millennia, the spring habitat of the North Atlantic right whale. Although there remain less than five hundred individuals on Earth, I’ve seen them eating in April right off the beach, skim-feeding for copepods, for brit. The North Atlantic right whale spends the summers feeding on zooplankton concentrations in coastal New England and the Canadian Maritimes and then swims south in the winter to mate and give birth off the coast of Georgia and Florida. They raise one calf every three to five years and have a twelve-month gestation cycle that has evolved to match that migration.31

Thoreau almost certainly never saw a North Atlantic right whale. Melville probably didn’t, either. The seemingly imminent loss of the North Atlantic right whale, which likely would’ve already happened decades ago if it weren’t for the inspiring and committed work led by a handful of biologists and environmentalists working out of Provincetown and elsewhere, is not simply about a loss of diversity or even a blow to human cultural values. The loss of whale abundance in the waters off New England has far-reaching ecological implications that are only beginning to be understood. The reduction of the relative abundance of large whales since human hunting has affected entire ocean ecosystems. By using genetic data, Joe Roman and Steve Palumbi estimated that the population of humpbacks, fins, and minke whales in the Gulf of Maine before whaling was between six and twenty times more than today. In other words, where researchers now estimate 10,000 humpback whales, Roman and Palumbi believe there was once near a quarter million.32

The impact of this loss of whale abundance is not simply that there would now be more squid and fish in the water. Whales energize ocean ecosystems; they are crucial in “lively grounds” from the top down. Even today in their diminished populations, baleen whales are enormous consumers and predators, skimming and gulping, for example, between eight to eighteen percent of all net primary productivity off the northeast continental shelf of North America.33 Roman, along with another colleague, James McCarthy, estimated that all that marine mammal excrement in the Gulf of Maine accounts for more input of nitrogen—a nutrient essential for phytoplankton—than all of the rivers that feed into this shoulder of the Atlantic.34 And the individual and aggregate biomass of large whales when they die, sink, and decay, creates entire localized ecosystems as they degrade. Thus, just as predators and grazers are essential to healthy ecosystems on land, when more whales swam in the Gulf of Maine, marine life of all kinds was more abundant—more swordfish, more herring, more copepods—far more than what Melville would’ve seen sailing away from New England in 1841.

As Melville was composing Moby-Dick, Thoreau was walking along the beaches of Cape Cod, judging the locals eating pilot whale sandwiches. He was stunned by the open expanse of beach and indifferent sea. Thoreau wrote in Cape Cod:

Though once there were more whales cast up here, I think that it was never more wild than now. We do not associate the idea of antiquity with the ocean, nor wonder how it looked a thousand years ago, as we do of the land, for it was equally wild and unfathomable always. The Indians have left no traces on its surface, but it is the same to the civilized man and the savage. The aspect of the shore only has changed. The ocean is a wilderness reaching round the globe, wilder than a Bengal jungle, and fuller of monsters, washing the very wharves of our cities and the gardens of our sea-side residences. Serpents, bears, hyenas, tigers, rapidly vanish as civilization advances, but the most populous and civilized city cannot scare a shark far from its wharves. It is no further advanced than Singapore, with its tigers, in this respect. The Boston papers had never told me that there were seals in the harbor. I had always associated these with the Esquimaux and other outlandish people. Yet from the parlor windows all along the coast you may see families of them sporting on the flats. They were as strange to me as the merman would be. Ladies who never walk in the woods, sail over the sea. To go to sea! Why, it is to have the experience of Noah,—to realize the deluge. Every vessel is an ark.35

Thoreau’s perspective on the ocean was that it was a cold, indifferent, wild otherworld. His view, in print only a few years after Moby-Dick, has poignant convergent similarities to Ahab’s final thoughts at the masthead, the day he was to die in the hunt for the White Whale, as well as Ishmael’s apostrophe to the merciless ocean in “Brit.” Both Melville and Thoreau compared the American view of the shore to that of the sea. They both saw a cold reality to the shipwreck and the storm.

For all its ferocity and indifference and otherness—its outlandishness—the ocean in the American mid-nineteenth century still held the healing, reassuring view of a watery wilderness beyond human reach.