Ch. 23

MOTHER CAREY’S CHICKENS

Omen? omen?—the dictionary! If the gods think to speak outright to man, they will honorably speak outright; not shake heads, and give an old wives’ darkling hint.—Begone!

Ahab, “The Chase—First Day”

One night soon after the ship enters the Pacific, the ocean where he will meet the White Whale, Ahab clops over on his ivory leg to visit with Perth, the blacksmith.

“Withdrawing his iron from the fire,” Ishmael says, “[Perth] began hammering it upon the anvil—the red mass sending off the sparks in thick hovering flights, some of which flew close to Ahab.”

“Are these thy Mother Carey’s chickens, Perth,” asks Ahab, referring to the sparks, “they are always flying in thy wake; birds of good omen, too, but not to all;—look here, they burn; but thou—thou liv’st among them without a scorch.”1

Although this bird is mentioned only once directly by name in Moby-Dick, it’s a compelling animal on which to hover for a moment before the Pequod sails into the tempest. Again, Melville leans on sailors’ experience with ocean species while also drawing upon sailors’ lore and his numerous fish documents on his farmhouse shelves.

A Mother Carey’s chicken is a storm petrel. Most ornithologists today agree to about twenty-two separate species of these birds in two families, the Hydrobatidae and the Oceanitidae. Nearly all storm petrels have mostly charcoal-brown feathers, blue-black webbed feet, and a black beak with a short tubenose to excrete salt—like tiny albatrosses. Generally only a bit heavier and longer than your average swallow, with similarly shaped wings, storm petrels are the smallest of the ocean-going seabirds. Yet storm petrels can survive several months or longer on the cold open ocean, in part due to a thick layer of fat under the feathers. Aboard the Charles W. Morgan, James Osborn read exulting prose about storm petrels in his copy of Good’s Book of Nature, which included, inaccurately, that these birds survived on oil alone, especially from dead whales and fish. The word petrel might come from “Petrello,” Italian for little Peter, since these birds pitter-patter over the surface, more often nibbling on plankton or fish eggs while still in the air, a behavior that has evoked for some the biblical story of St. Peter stepping over the waves. Ahab’s comparison to these birds as sparks flying aft is appropriate, because when not hovering just over the surface, the storm petrel’s flight is quick and sharp. They’re known to follow ships, perhaps to benefit from the food stirred up in a vessel’s wake.2

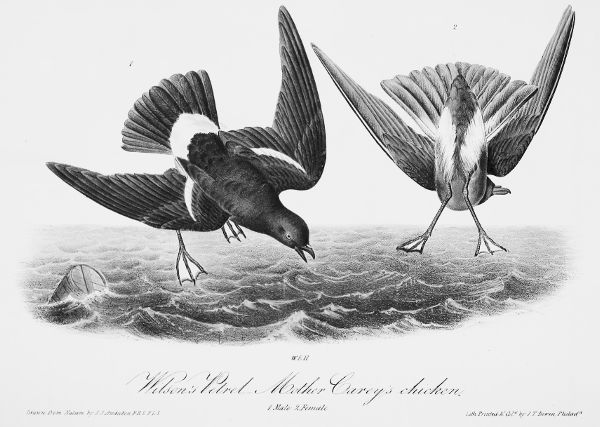

Sailors in Melville’s time, like Ahab, did indeed call storm petrels “Mother Carey’s chickens,” which might derive from the Latin Mater Cara, meaning Virgin Mary, the protector of sailors. The common name was so well known that in the 1830s John James Audubon felt compelled to add it to the label of his painting of two Wilson’s storm petrels (see fig. 45).3

FIG 45. John James Audubon’s Wilson’s Petrel—Mother Carey’s chicken (Oceanites oceanicus) in his Birds of America (1827–1838).

Before writing Moby-Dick Melville surely heard them called Mother Carey’s chickens at sea. As one example of how sailors like Melville used the common name, consider an entry on August 19, 1849, by harpooner Isaac Jessup of the Long Island whaleship Sheffield. Two days outward bound, he wrote: “To day is the 1st Sabbath I spend on sea & I must own it is far from a pleasant one. Seasickness is taking away all my strength & rendering me unfit for labor of any kind. Of home or church or anything else I have scarcely thought. Our course is changed to easterly. Mother Carey’s chickens are abundant.” I love that little entry not just as an example of the sailor’s name for storm petrels, but also for its reminder of the strains of life at sea and the ever-present lens of the Christian faith for so many American mariners—the Starbucks out at sea.4

And Melville clearly had a soft spot for storm petrels. In his “The Encantadas” (1854), published only a couple years after Moby-Dick, Melville wrote in more detail about storm petrels, describing them as “this mysterious humming-bird of ocean, which had it but brilliancy of hue might from its evanescent liveliness be almost called its butterfly, yet whose chirrup under the stern is ominous to mariners as to the peasant the death-tick sounding from behind the chimney jam.”5

Just as Coleridge drew from sailors’ superstitions with his albatross in “The Ancient Mariner” and Melville did earlier in Moby-Dick with his “sea-ravens” in “The Spirit-Spout,” Melville used Mother Carey’s chickens for poetic effect in “The Forge.” Melville knew that sailors often associated storm petrels with dangerous weather. In that passage from “The Encantadas,” the storm petrels’ chicken-like clucking frightens the mariners. Though some superstitious voyagers believed the birds were divinely sent to warn them of danger, to aid the men, other mariners thought these petrels caused the storms and even that the birds were a morph of witches. Mad Ahab welcomes the Mother Carey’s chickens as a good omen, a sign of the coming typhoon.6

Storm petrels do not cause storms, of course, but their visibility to humans may increase during times of heavy weather, as Melville’s fish documents explained, because the little birds seek refuge on or near ships, or, perhaps, more likely, this is simply a time when ships are sharing the same element with these tough seabirds. I once held one that had landed and got trapped in a small boat of our schooner during a gale in the Caribbean Sea. It felt as light as a child’s balled sock. When I worked on a lobsterboat in Long Island Sound, we saw storm petrels only during nasty weather. Presumably they were blown in by a gale from the North Atlantic, or that’s simply when they prefer to come closer to shore. And once when sailing quietly on the Grand Banks on a small boat, I saw storm petrels trailing astern. It was the first time I had ever heard their chirrupy-chirping sound. Storm petrels have a light clucking, chortling call, which I think might also have contributed to the “chickens” nickname. They followed astern of my boat for a couple days, appearing around dusk and early evening. There was something spooky and bat-like about their little black following flight.7

In “The Forge,” after Ahab’s dark comment about the blacksmith’s sparks flying astern like Mother Carey’s chickens, the captain asks Perth to forge a harpoon strong enough to kill the White Whale. In one of the most heretical scenes in the novel, Ahab then commands the harpooners to come temper the iron with their blood, blessing the weapon under the name of the Devil. The image of the sooty gray Mother Carey’s chickens as sparks sets this scene, charges the lighting, for the literal and metaphorical storms that loom at the end of this chapter and in the days to follow.