NEARLY TWO DOZEN FIRES BURNED OUT OF CONTROL across Charleston on Saturday, February 18, 1865, as the Union Army moved into the Cradle of the Confederacy. The brutal 545-day siege had reduced much of the city to rubble, leaving gaping holes in buildings across the lower peninsula. Witnesses compared Charleston to the ruins at Pompeii.

But the city quickly came alive as the Union soldiers advanced into Charleston—and not just because they helped to put out the flames. Thousands of former slaves thrilled at the sight of their liberators, most of whom were members of the 21st United States Colored Troops. “As boat after boat landed, on the morning of the 18th, our troops were received with cheers, prayers, cries, and countless benedictions by the negroes,” wrote Kane O’Donnell, correspondent for the Philadelphia Press. “The colored soldiers were hugged and kissed by the women of their race, and clasped in the arms of brothers.” Just hours after the liberation of the city, hundreds of men, women, and children welcomed a company of the black 54th Massachusetts Infantry, which marched across the Citadel Green. “Shawls, aprons, hats, everything was waved,” observed northern minister C.H. Corey. “Old men wept. The young women danced, and jumped, and cried, and laughed.”1

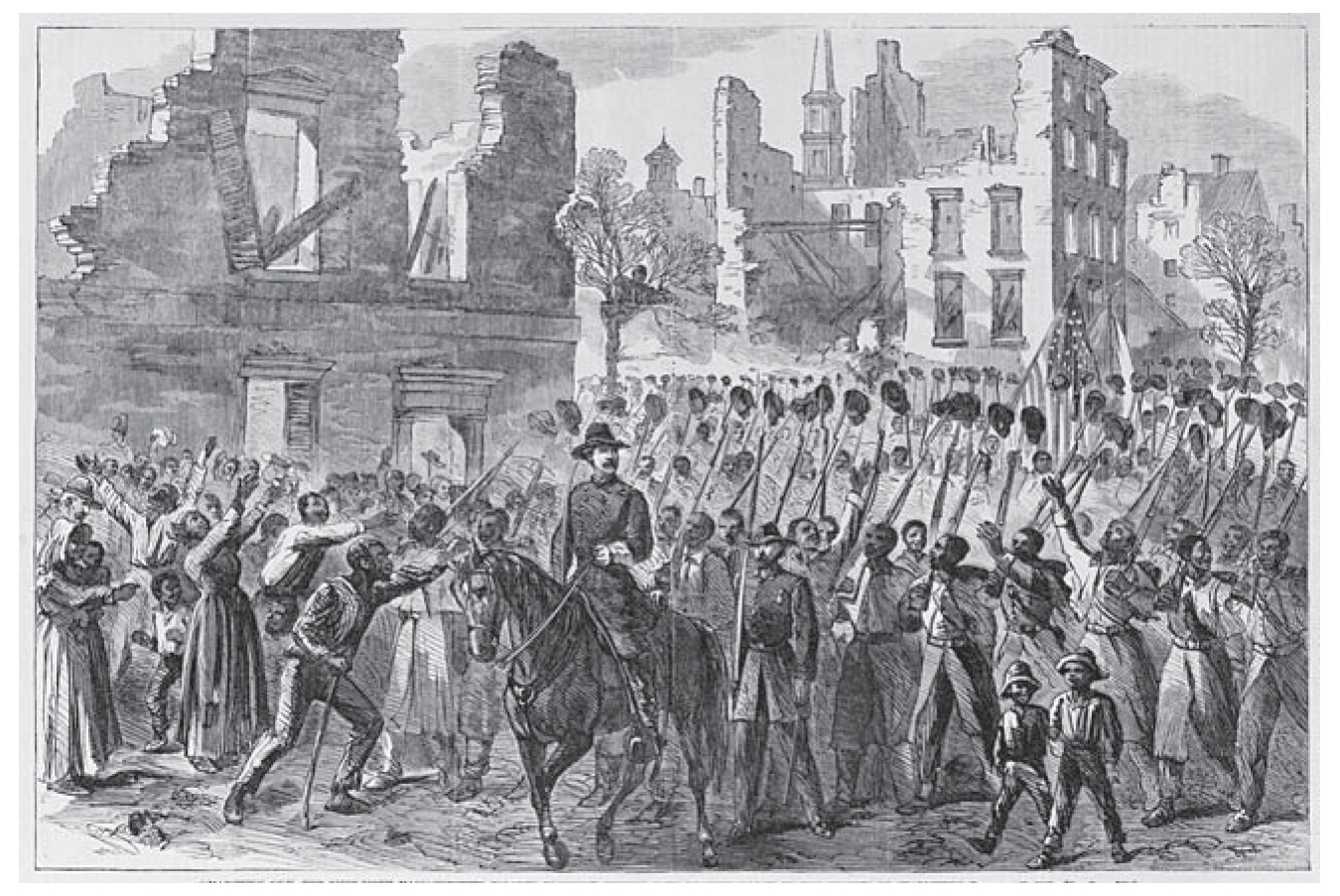

Three days later, on February 21, the Massachusetts 55th Regiment arrived, singing “John Brown’s Body” to the African American crowds that cheered them on. “Imagine, if you can,” wrote New-York Tribune correspondent James Redpath, “this stirring song chanted with the most rapturous, most exultant emphasis, by a regiment of negro troops, who have been lying in sight of Charleston for nearly two years—as they trod with tumultuous delight along the streets of this pro-Slavery city.” Some of the men in the 55th had once walked Charleston streets as slaves. But now they proudly marched through Charleston as free men, American soldiers, and saviors of the nation. Freedpeople assembled again on February 27 to receive the rest of the Massachusetts 54th. “On the day we entered that rebellious city, the streets were thronged,” commented John H.W.N. Collins, a black sergeant. “I saw an old colored woman with a crutch,—for she could not walk without one, having served all her life in bondage,—who, on seeing us, got so happy, that she threw down her crutch, and shouted that the year of Jubilee had come.”2

After a lengthy Union siege, much of Charleston was in ruins when the Union Army occupied the city in 1865.

Over the next several months, as the Civil War ground to a halt, local freedmen and -women and the occupying Union force came together time and again to mark Union victory and the end of the peculiar institution with parades, commemorations, and other public demonstrations. Collectively, they transformed Charleston from the birthplace of secession into the burial ground for slavery. Although the city had been practically burned to the ground, revelry reigned. In this opening stage of the long struggle over the memory of slavery, former slaves and their allies held the upper hand.

On February 21, 1865, the Massachusetts 55th marched into the city singing “John Brown’s Body” to the delight of the black citizenry. From Harper’s Weekly, March 18, 1865.

* * * *

THROUGHOUT THE SPRING and summer of 1865, freedpeople flocked to Charleston. Some had lived all their lives in the Piedmont, Upcountry, or the surrounding Sea Islands; others were returning home after being removed to the interior by their masters. Believing that “freedom was free-er” in towns and cities than on isolated plantations, these former bondpeople made Charleston an African American–majority city once more.3

As was true across the South, Charleston’s freedpeople set about rebuilding their lives and reconstructing their families as best they could. Once-trusted servants wasted little time in demonstrating where their true allegiance lay. Less than two weeks after the city fell, one thousand black Charlestonians joined the Union Army, a brisk pace that kept up through April under the stewardship of Major Martin R. Delany, the first black officer commissioned at that rank. Among the new recruits was fifteen-year-old Archibald Grimké, who emerged from the shadows to serve as an officer’s boy.4

These new volunteers joined with more seasoned Union soldiers and the rest of the city’s black population to mark the death of slavery with a yearlong wake. From impromptu gatherings to elaborately planned affairs, these “festivals of freedom”—as the black abolitionist William C. Nell once dubbed such pageants—helped put slavery at the center of Civil War commemoration.5

Perhaps the most memorable festival of freedom that spring occurred on Tuesday, March 21, when between four thousand and ten thousand people gathered at the Citadel Green. It was a scene laden with irony. For decades the park had served as a parade ground for the adjacent South Carolina Military Academy, also known as the Citadel. But now the square where white cadets charged with protecting the city against slave insurrection had conducted public exercises became the gathering point for a parade of black Union soldiers and countless African Americans. According to New-York Tribune reporter James Redpath, the assembled viewed the procession as “a celebration of their deliverance from bondage and ostracism; a jubilee of freedom, a hosannah to their deliverers.”

The parade, which stretched more than two miles long, started at about 1 p.m. under rainy skies. It took several hours to wind its way down King Street to the Battery at the base of the peninsula and then back to the Citadel Green. Led by dignitaries on horseback and a marching band, the procession also included tradesmen, fire companies, and nearly two thousand recently enrolled schoolchildren. A company of boys marched behind a banner reading “We know no masters but ourselves.” They were followed by “A Car of Liberty,” which carried fifteen young women representing the fifteen slave states. Clad in white dresses—outfits no doubt chosen to evoke the purity and virtue once associated exclusively with white womanhood—they refuted the lowly status assigned to black women, enslaved or free. The 21st U.S. Colored Troops participated in the procession, too. With armed black men marching through town, southern white nightmares appeared to be coming true.

As if to put the lie to planter mythology about unruly blacks in need of discipline, Unionist accounts highlighted the order of the African American parade. Even the schoolchildren, with no experience and just one hour’s training, “kept in line, closed up, and were under perfect control,” reported James Redpath. The lone exception to this rule came with the students’ rendition of “John Brown’s Body,” which they sang throughout the march. Although they had been instructed to omit the verse, “We’ll hang Jeff. Davis on a sour apple tree!” they belted it out again and again.

The most striking feature of the freedpeople’s procession was a large mule-drawn cart bearing a sign that read, “A number of negroes for sale.” The cart also carried an auction block and four African Americans—one man, two women, and a child—all of whom had been sold at some point in their lives. The man playing the role of auctioneer cried out to the crowd along the parade route, “How much am I offered for this good cook? . . . Who bids?” Behind the mock auction cart trailed a simulated slave coffle comprising some sixty men “tied to a rope—in imitation of the gangs who used often to be led through these streets on their way from Virginia to the sugar-fields of Louisiana.”6

The participants in this carnivalesque bit of street theater meant to ridicule the chattel system that had victimized millions of black southerners, and the show did, in fact, produce “much merriment,” according to one observer. Yet, as Redpath wrote, “old women burst into tears as they saw this tableau, and forgetting that it was a mimic scene, shouted wildly: ‘Give me back my children! Give me back my children!’” Just a couple of months removed from the final slave sale in Charleston—a mock auction of a different sort, with the slave system crumbling around it—the tableau may well have touched a still-raw nerve. Or, perhaps their emotional display was a calculated move intended to remind those watching the parade—and those who would read about it from afar—that although slavery was over, the pain of what it had cost them endured. Following the auction cart and slave coffle came a more unambiguously humorous element of the tableau: a hearse carrying a coffin labeled “Slavery,” which elicited laughter from the audience.

This mock funeral harkened back to the raucous funeral rites performed by the enslaved in many southern cities as well as to a broader American tradition that dated back to the 1700s. During the Revolution, patriots marched through the streets with caskets, testifying to their anger at the actions of British authorities. More recently, in 1854, Boston abolitionists protesting the rendition of runaway slave Anthony Burns had suspended a large black coffin, with the word “Liberty” painted on it in white, along the route by which Burns was marched back into bondage under armed guard. Now, the tables were turned, and the funeral march was for slavery, not freedom. Scrawled in chalk on the hearse were the inscriptions “Slavery Is Dead,” “Who Owns Him,” “No One,” and “Sumter Dug His Grave on the 13th of April, 1861.” A long train of female mourners dressed in black followed behind the coffin, their smiling faces the only tell of their true sentiments.7

“Charleston never before witnessed such a spectacle,” concluded the New York Times correspondent of the day’s events. “Of course, this innovation was by no means pleasant to the old residents, but they had sense enough to keep their thoughts to themselves. The only expressions of dislike I heard uttered proceeded from a knot of young ladies standing on a balcony, who declared the whole affair was ‘shameful,’ ‘disgraceful.’”8

Surrounded by black soldiers and their former slaves, the few whites who remained in Charleston were too chastened to protest. Although a handful of Confederates insisted that their cause was not yet lost, most locals scrambled to demonstrate their allegiance to the United States by taking the loyalty oath. Northerners marveled at the new climate in Charleston. “I have given utterance to my most radical sentiments to try their temper, and have not even succeeded in making any one threaten me by word, look or gesture,” noted Boston Daily Journal correspondent Charles Coffin in late February. “William Lloyd Garrison or Wendell Phillips or Henry Ward Beecher can speak their minds in the open air . . . without fear of molestation.”9

Three weeks later, Garrison and Beecher would do just that. The abolitionists traveled south to Charleston along with hundreds of allies for the first government-sponsored festival of freedom, held on April 14, 1865, which was, coincidentally, Good Friday. Four years earlier to the day, Major Robert Anderson had lowered the American flag, surrendering the federal installation at Fort Sumter to Confederate General P.G.T. Beauregard and inaugurating four years of war. Now, just days after Robert E. Lee and his Army of Northern Virginia had yielded to Ulysses S. Grant at Appomattox Court House, signaling an end to the Civil War, Anderson returned to raise the very same flag in the very same place. Many Americans viewed Charleston as the Cradle of the Confederacy. Hereafter, predicted one northern minister, the city would be known as “at once its cradle and its grave.”10

President Abraham Lincoln and his cabinet understood the symbolic significance of the occasion. While the flag-raising ceremony itself signaled political and military victory, they made sure to include individuals who would underscore the revolutionary social changes wrought by the conflict. Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton asked Henry Ward Beecher, a renowned orator and vocal critic of slavery, to give the ceremony’s keynote address. A good portion of Beecher’s Brooklyn congregation joined him on the venture. Stanton also invited William Lloyd Garrison—the most famous abolitionist in America, a man who had once publicly burned the Constitution—and British abolitionist George Thompson to attend the ceremony as official guests of the government. Several other prominent opponents of slavery joined Beecher, Garrison, and Thompson, including black reformer and army major Martin R. Delany, newspapermen Theodore Tilton and Joshua Leavitt, and Senator Henry Wilson of Massachusetts. Among the homegrown abolitionists were Robert Smalls, the former slave who had dramatically seized his freedom by commandeering the Confederate ship the Planter in Charleston three years earlier, and Robert Vesey, son of Denmark Vesey.11

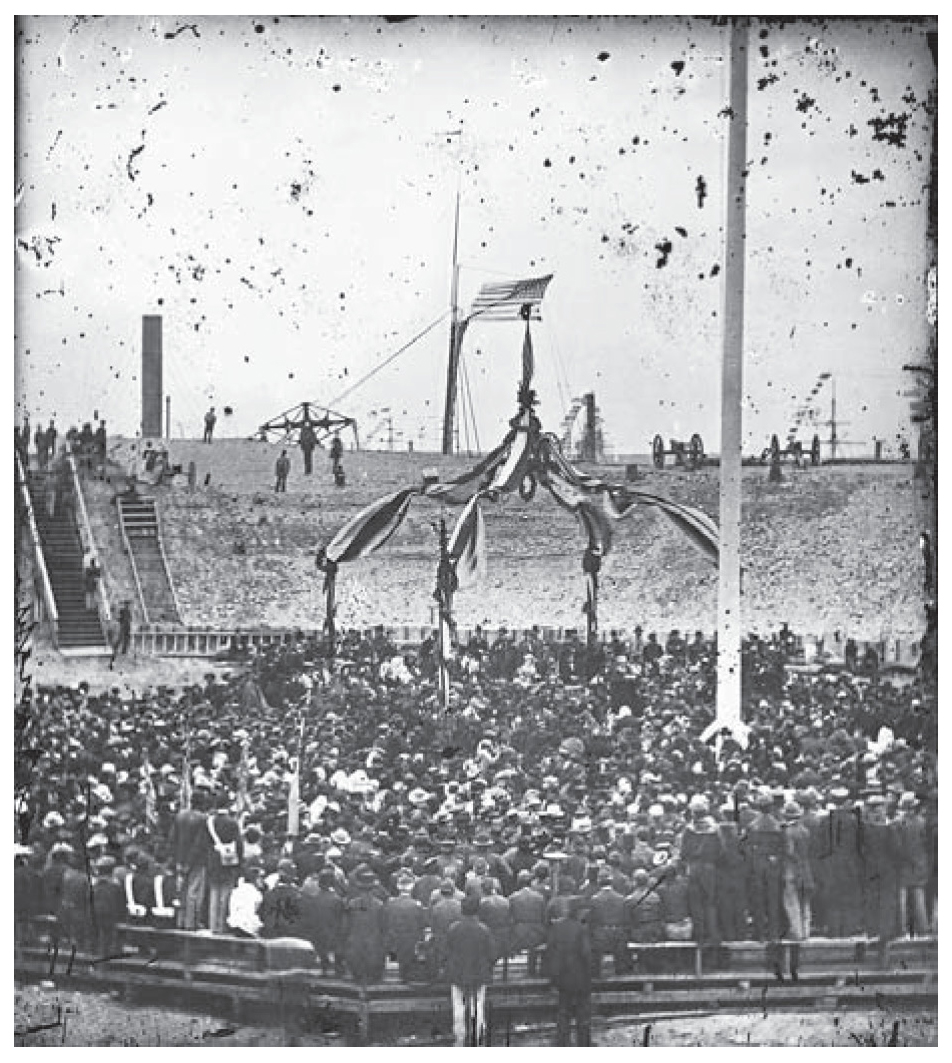

At ten o’clock in the morning on April 14, boats began ferrying people—northern and southern, soldier and civilian, white and black, all now free—out to Fort Sumter. Some made the short journey in steamships, while a number of the freedpeople ventured into the water in flats and dugouts, hoping that they might be picked up by a larger vessel, perhaps the legendary Planter. Still captained by Smalls, the ship ferried ex-slaves to Fort Sumter under an overcast sky.12

Like Charleston, the tiny man-made island at the mouth of the harbor was a bombed-out shell of its former self. “Fort Sumter is a Coliseum of ruins,” Theodore Tilton wrote. “Battered, shapeless, overthrown, it stands in its brokenness a fit monument of the broken rebellion.” More than three thousand people, including members of a black regiment commanded by Beecher’s brother James, filled the fort, some spilling out onto its crumbing walls.

The ceremony opened with a song, a short prayer, and recitations of several psalms as well as Major Anderson’s 1861 dispatch of surrender. Then, after saying a few words, Anderson and a dozen men, including George Thompson, lifted the enormous flag that had been taken down four years before. As “the old smoke-stained, shot-pierced flag” rose, so, too, did everyone in the fort. Waving hats and handkerchiefs, the spectators erupted with shouts, laughter, and tears when the flag reached its peak. “It was the most exciting moment in my life when the flag went up,” wrote Brooklyn pastor Theodore Cuyler.

On April 14, 1865, thousands of people gathered at Fort Sumter for a flag-raising ceremony that commemorated the end of the Civil War.

Beecher approached his keynote address, which followed soon after, in a spirit of Christian forgiveness. He pulled no punches, however, in assigning blame for the war—“the ambitious, educated, plotting political leaders of the South”—or in praising its radical results. “The soil has drunk blood, and is glutted,” he admitted, but the time had come “to rejoice and give thanks.” In unfolding the flag at Fort Sumter, the assembled were restoring the peace and sovereignty of the nation. “No more war! No more accursed secession! No more slavery, that spawned them both!” Beecher intoned to great applause.13

That evening, Major General Quincy A. Gillmore hosted a banquet at the Charleston Hotel. After dinner, the guests offered up a series of toasts. Abraham Lincoln was on the mind of many that night. Perhaps most moving were the words of Garrison, a longtime critic of the president. “Of one thing I feel sure,” announced the editor, “either he has become a Garrisonian Abolitionist or I have become a Lincoln Emancipationist.” Whatever the case, Garrison concluded that Lincoln’s “brave heart beats for human freedom everywhere.” Little did he or anyone else in Charleston know that the president’s brave heart would not beat much longer. For that same night, as abolitionists and federal officers in the Charleston Hotel cheered the maintenance of the Union and the end of slavery, Lincoln’s assassin John Wilkes Booth made it clear that for some Confederates the war was not over.14

Charleston still had its fair share of unreconstructed rebels, too. Writing from her residence on South Bay Street on April 14, Maria Middleton Doar fumed over the “crowds of Negro women accompanied by men in uniform parading on the battery” while they waited for the flag to be raised at Fort Sumter. “There is to be a ball tonight at Cousin W[illiam Middleton]’s house,” she told a cousin. “Would you believe that some Charleston ladies are going[?]” Doar was happy to report that “most of those who have been insulted by invitations have indignantly refused.”15

Outside the city, Confederate sympathizers also stewed. In May, Emma Holmes, an elite young woman who had moved from Charleston to Camden midway through the war, wrote in her diary that the word from home was that a “grand Union glorification” had taken place on Good Friday. Among the fooleries of the day, she complained, were the flag-raising ceremony, a parade of the city’s black residents, and a “‘promiscuous’ ball” held at the Middleton residence—the same ball that troubled Maria Middleton Doar. Holmes found a measure of satisfaction in reports out of Charleston that “the really respectable class of free negroes, whom we used to employ as tailors, boot makers . . . etc., won’t associate at all with the ‘parvenue free.’”16

Other white southerners traded stories—some true, many false or exaggerated—of the theft and destruction of private property, plots of black insurrection, and worse. Perhaps prompted by the Slavery Is Dead procession on March 21, a Newberry, South Carolina, newspaper reported on April 6 that a group of black Charlestonians had recently put up slave trader John S. Riggs at a mock auction. The following week, Emma LeConte, of Columbia, seethed in her diary that Charleston recently “had a most absurd procession described in glowing colors and celebrating the Death of Slavery.” It was a world turned upside down. “Abolitionists delivered addresses on the superiority of the black race over white. . . . Also, ‘As Christ died for the human race, so John Brown died for the negroes,’ etc., etc.” Emancipation aroused white southerners’ deepest fears. “Abolition seems to be in full black” in Charleston, reported the Columbia Phoenix on March 21. “From the rumors which reach us, miscegenation is soon likely to follow.”17

* * * *

OPPONENTS OF SLAVERY rejoiced over the news of Charleston’s festivals of freedom. In Columbia, the newly liberated asked for “permission to follow the example of Charleston negroes and bury slavery with pomp and ceremony.” Up north, hundreds of thousands of Americans read the moving columns on the city’s emancipation published in newspapers such as the New-York Tribune, the Boston Daily Journal, and the Philadelphia Press. Much of this coverage also featured reporters’ firsthand accounts of their search for the remains of Charleston’s slave regime. Inspired by such stories, scores of northerners made pilgrimages to the former capital of American slavery, touring its holy sites—the slave-trading district, the Work House, the Citadel, the offices of the Charleston Mercury—and often picking up a keepsake or two to take back home.18

These excursions reflected the popularity of memento collecting in the nineteenth century, when middle-class Americans traveled to historical sites to gather relics that they believed would help them forge a deeper connection with the nation’s past. This phenomenon reached its apex during the Civil War. Soldiers and civilians in both the North and the South saved objects that reminded them of the conflict, from fragments of battle-scarred trees to bullets that had pierced loved ones.19

In early April, abolitionist Theodore Tilton visited the place many believed was the ideological epicenter of both slavery and the Civil War: the gravesite of John C. Calhoun. No fan of Calhoun, Tilton was nonetheless disturbed to find that relic seekers had desecrated the statesman’s tomb. The New York editor chose a less destructive method to acquire his memento of Charleston, plucking some clover growing near the ruins of Institute Hall, where the Ordinance of Secession had been signed in 1860. James Redpath, for his part, grabbed a keepsake from the Charleston Mercury offices. When the antislavery reporter had visited the battered newspaper headquarters in late February, he found some printer’s type that editor Robert B. Rhett Jr. had set up for its final issue. Redpath absconded with it “for posterity.”20

Redpath also joined with a number of other northern visitors who pillaged Charleston’s slave-trading district for what he called “relics of barbarism.” After Charleston had outlawed public slave sales outside the Exchange Building, most auctions had been conducted in the buildings and offices clustered on Chalmers and State streets. Charles Coffin recorded a detailed account of his visit to Ryan’s Mart, the most prominent of such venues. The Boston Daily Journal correspondent entered the Chalmers Street complex through an iron gate, above which sat the word “Mart” in gilt letters. Behind the gate, he found a sizable hall, with an auction table running the length of the structure and ending at a locked door. With the help of a freedman, Coffin broke through the wooden door, gaining entry to the rest of the complex. At one end of the yard, which was walled in on all sides, was the four-story brick prison known as Ryan’s Jail. Next to the hall was a small room—“the place where women were subjected to the lascivious gaze of brutal men.”

Coffin focused his gaze on “the steps, up which thousands of men, women and children have walked to their places on the table, to be knocked off to the highest bidder.” The journalist decided to take the steps back with him to New England. “Perhaps,” he reasoned, “Gov. Andrew, or Wendell Phillips, or Wm. Lloyd Garrison . . . would like to make a speech from those steps.” Coffin also secured two locks and the gilt letters from the front of Ryan’s Mart. Other accounts suggested that Coffin and his colleagues acquired a slave-market bell, manacles, and the correspondence of local slave dealers. These abolitionist raiders did not sweep Charleston’s slave markets clean, however. Among the items they left behind was a slave trader’s desk on which someone had inscribed antislavery messages from William Lloyd Garrison and John Brown.21

Many slavery relics did find their way into the hands of northern reformers. Wendell Phillips was reported to have received a slave-market bell as a gift from a Massachusetts man, most likely James Redpath. Philadelphia Press correspondent Kane O’Donnell gathered papers from several slave marts. His newspaper subsequently published excerpts from these documents, which included correspondence between Charleston slave dealers and prominent public figures, such as former governor James Henry Hammond and the Confederacy’s first two secretaries of the treasury, Christopher Memminger and George Trenholm.22

A few weeks after he toured the slave-trading district, on March 9, 1865, Charles Coffin officially presented some relics to the Eleventh Ward Freedmen’s Aid Society at the Boston Music Hall before a large audience. In a striking display, the auction block steps from Ryan’s Mart were placed on the very stage from which antislavery minister Theodore Parker once rained invective down upon slaveholders in his Sunday sermons. The lock to the slave pen was placed on the Music Hall’s desk, and the gilt letters “Mart” were suspended from the organ. Coffin regaled the crowd with stories about the Charleston slave trade, reading from a broker’s papers.

Later, fulfilling the wish Coffin had expressed when he salvaged the auction block steps, William Lloyd Garrison mounted them in order to put “the accursed thing under his feet.” Standing atop the steps—portals into the enslaved past—the abolitionist editor sought to enhance his connection to the people for whom he had fought so long. The Music Hall crowd erupted in thunderous applause, waving white handkerchiefs in celebration, before Garrison offered a lengthy lecture. Over the next few weeks, Garrison, George Thompson, and other antislavery colleagues re-created this scene at Freedmen’s Aid Society meetings in Lowell and Leicester.23

One month after Garrison mounted the auction block steps in Boston, he and Thompson set sail for Charleston for the April 14 flag-raising ceremony at Fort Sumter. While in Charleston, Garrison and many of his antislavery colleagues combed the city in search of slave sites. Although northern teacher Laura Towne’s sightseeing was limited by seasickness, she made sure to see the Work House. Still standing amidst the burned-out shells of homes and businesses in the lower part of the peninsula, the Gothic building looked “like a giant in his lair.” Towne wanted to confirm that the building she found was, indeed, the despised Sugar House, so she asked an elderly black woman standing nearby. “Dat’s it,” she responded, “but it’s all played out now.”24

Other visitors that weekend followed the path blazed by Coffin and Redpath. After describing the tiny dens that held the enslaved on their way to the auction block as “dark, filthy, and horrible” in the Independent, for instance, Brooklyn minister H.M. Gallaher noted the too-good-to-be-true name of one of the city’s slave-auction firms: Clinckscales and Boozer. “Well,” Gallaher concluded sarcastically, “they will clink no more the dollar that has blood upon it, and booze no longer on the money that made mad a slave mother.”25

Henry Ward Beecher strolled through Charleston on Saturday morning, April 15, the day after the Fort Sumter flag raising, seeing reminders of slavery—and its demise—all over town. At one point, he called on former governor William Aiken Jr., who lived in an imposing home not far from the Citadel Green. Aiken had owned close to one thousand slaves before the war. Beecher hoped to talk about the future with Aiken, a prominent Unionist, but the governor seemed drawn incessantly back to one point: “The President ought not to have issued his Proclamation.” Aiken spoke of his relationship with his slaves in “couleur de rose.” The governor’s tales were familiar. “There is a liturgy on this subject,” wrote Beecher. “You may take a thousand Southerners at Saratoga and Newport, and they will all repeat the same story of their care and nurture of the slaves, and of the addiction of the slaves to them.” The next day, Beecher spoke directly to Aiken’s former slaves, who gave him an altogether different impression. “We shall never know what slavery is,” he concluded, “until the slaves tell us.”26

Later that morning, Beecher joined George Thompson, Henry Wilson, Theodore Tilton, and Garrison on a visit to John C. Calhoun’s tomb. “All this great crop of war,” maintained Beecher, “is from the dragon-toothed doctrines that were sowed by the hands of that dangerous man.” In what one eyewitness described as being among the most striking scenes of the extraordinary weekend, Garrison put his hand on the simple marble slab, which was inscribed with just a single name: Calhoun. “Down into a deeper grave than this slavery has gone,” he said, “and for it there is no resurrection.” The abolitionists stood in silence as Garrison’s pithy obituary hung in the air before walking the short distance over to the Citadel Green. Thirty years earlier, white Charlestonians had gathered on that parade ground to burn antislavery tracts and an effigy of Garrison in a large bonfire. But on April 15, 1865, the Citadel Green played host to thousands of black Charlestonians who were listening to the words of Martin R. Delany.27

That afternoon, a vast crowd packed into Zion Presbyterian Church, adjacent to the green on the corner of Calhoun and Meeting streets, to listen to speeches by Garrison, Thompson, and Henry Wilson, among others. At the start of the program, an ex-slave named Samuel Dickerson came forward with his two small daughters, each of whom carried a bouquet of flowers. Dickerson, who would become a lawyer and Republican activist in the decade that followed, welcomed Garrison with moving words. The Massachusetts abolitionist replied that he was incapable of expressing the overwhelming emotions he felt as he listened to Dickerson and looked into the faces of the enormous audience. Reminding them that he had been fighting slavery for nearly four decades, Garrison confessed that he thought this day would never come. “Thank God this day you are free,” he proclaimed to great cheers. “And be assured that once free you are free forever.” Garrison also read from a record book that someone had recovered from a slave-trading firm, as well as a recent newspaper advertisement for “an active boy about fourteen years old.” Looking out at the black masses before him, the abolitionist editor asked, “Have any of you got such a boy to sell?” The crowd began to sway back and forth, scream, cry, and shout “No!”—an uncomfortable response reminiscent of the reaction elicited by the mock slave auction in March. At the close of the meeting, black Charlestonians escorted the abolitionists back to the Charleston Hotel, forming a procession that seemed a mile long.28

On Monday, April 17, as Beecher, Garrison, Thompson, and company prepared to leave Charleston, the crowds were even larger. “The streets were full of colored people,” wrote Beecher, who noted that Union soldiers, including Garrison’s own son George Thompson Garrison, had been busy liberating thousands of slaves from nearby plantations. Though desperately poor, the freedpeople who joined Garrison and his colleagues at the wharf offered whatever tokens of gratitude they could spare. Some carried roses, others honeysuckles. Samuel Dickerson offered another eloquent speech, and black children belted out songs. At ten o’clock in the morning, the abolitionists sailed out of Charleston, watching as Dickerson knelt at the wharf’s edge, one arm draped around his daughters and the other holding the American flag.29

* * * *

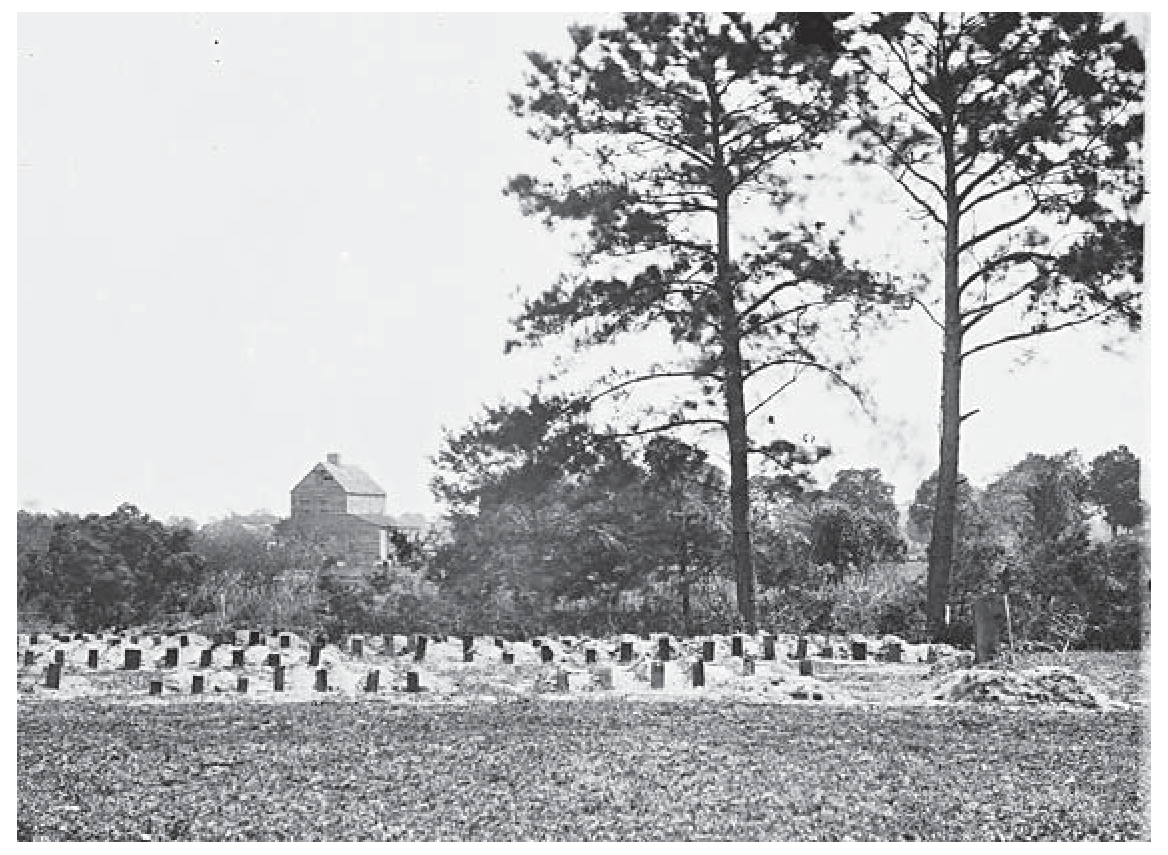

ALL SPRING, BLACK Charlestonians like Dickerson and Unionists in the city celebrated the end of the war and the demise of slavery with demonstrations, large and small. On May 1, 1865, they offered another elaborate tribute—this time to a group that had not only fought but also died for black freedom. On the northern outskirts of town, the remains of 257 Union prisoners of war were buried in unmarked graves. Held in a Confederate prison camp at Washington Race Course, these soldiers had suffered and died in the final year of the war. Union officers, northern reformers, and Charleston’s black community determined that their sacrifices should not be forgotten. By creating a suitable cemetery in which to bury the prisoners who had perished there, they sought to put the final nail in the coffin of slavery. In the process, they initiated the national day of remembrance that was originally called Decoration Day and is today marked as Memorial Day.30

The Union prisoners’ ordeal contrasted sharply with the experiences of those who had frequented the Washington Race Course before the Civil War. Since its opening in the early 1790s, the horse track had been the center of the South Carolina elite’s social world. Each winter, the region’s planter class gathered in Charleston, mingling at parties and watching the horses run. Even as wealthy southerners lost interest in horse racing by the 1840s in cities like Baltimore, Norfolk, and Richmond, South Carolina elites continued to congregate for—and invest significant meaning in—the Charleston races.31

The Civil War, however, brought the yearly festivities at the Washington track to an abrupt halt, and by 1864 the once grand venue was overgrown with grass, the judges’ stand looking as if it might fall over at any moment. Confederate forces built a makeshift prison there to hold between six thousand and ten thousand Union captives who in mid-1864 were evacuated from Georgia prisons, including the infamous one at Andersonville. The Charleston prison was not much better. “We had no tents and no shelter whatsoever furnished us,” wrote a Connecticut sergeant major of the wretched conditions. All the soldiers had to protect them from the elements were a few blankets, which “were of little use when it rained.” And rain it did. That September it seemed to pour day and night, making life at the racecourse even more miserable than usual. Weakened by the horrid conditions that they had endured at Andersonville, many of the prisoners stood little chance. “Men died about as fast, in proportion to their numbers, as at Andersonville,” explained one Massachusetts soldier. “Scurvy, diarrhea, and fever swept the prisoners off in vast numbers.”32

Local whites displayed little compassion for these Union captives. “I am sorry to say that I never heard of a native white doing any thing for the assistance of our prisoners in Charleston,” recalled an observer in 1865. Charleston’s black community, in contrast, fed the starving men. Some gave bread to the sickly Andersonville prisoners as they were marched into the city, while others brought food out to the racecourse prison, only to be driven away by the rebels. When Henry Ward Beecher visited for the Fort Sumter ceremony, he met four black women who had been whipped for secretly providing food, bandages, and medicine to the Union captives.33

As yellow fever swept through Charleston in the fall of 1864, Confederate officials decided to remove the prisoners held at the racecourse to Florence, South Carolina. They left behind hundreds of deceased prisoners, who had been rudely buried in a few rows without any grave markers. The following spring, on March 26, 1865, just days after the Slavery Is Dead parade, James Redpath and several other northern visitors ventured out to the Washington Race Course to see these graves.34

As a war correspondent for the New-York Tribune, Redpath had come to Charleston with Union troops one month earlier. It was not his first visit. After emigrating from Scotland to the United States in 1849, Redpath had traveled throughout the South secretly interviewing slaves, including in Charleston, and then telling their tales in abolitionist newspapers. He was thrilled not only to be able to report on the liberation of Charleston in the spring of 1865, but also to be offered the position of superintendent of education once there. Redpath swiftly reopened five city schools, enrolling children of all races for the first time. He also helped found a new black orphan asylum, named for Union martyr Robert Gould Shaw, in an East Bay Street mansion.35

Not long after he arrived in Charleston, Redpath began hearing tales about the racecourse prison. “The colored population here tell fateful stories of the sufferings of our prisoners, while many of the [ex-Confederate] oath-takers pretend to deny that any cruelties were practiced,” he wrote. “But their testimony is like their oath—false and for a purpose.” Beyond the memories guarded by Charleston’s black citizenry, the only traces of the racecourse prisoners that Redpath and his companions could find when they visited the site in March were small pieces of wood with numbers painted on them. The graveyard, such as it was, sat in an open space not far from the track. Nothing was erected to protect the graves from grazing cattle.36

In the spring of 1865, black Charlestonians cleaned up and built a fence to protect the Union burial ground at the Washington Race Course.

Outraged by this show of disrespect to the Union dead, Redpath and company formed themselves into a committee to raise money to construct a more appropriate gravesite. The committee was headed by Redpath and consisted chiefly of white Union officers, reformers, and ministers, though it included at least one local African American: Robert C. DeLarge, a freeborn black who would later serve in the House of Representatives. They immediately drafted a circular that solicited contributions of ten cents from all loyal South Carolinians in order to “give everyone the privilege and debar none from aiding this noble work.” In response to this appeal, approximately five thousand African Americans met at Zion Presbyterian Church, where twenty-eight local black men agreed to build a fence for the racecourse gravesite.37

This was not the first time local blacks had sought to commemorate the sacrifices of Union soldiers. In July 1863, Colonel Robert Gould Shaw had led the 54th Massachusetts Infantry on a failed frontal assault of nearby Fort Wagner, leaving Shaw and many of his men dead. Soon after, the surviving members of the Massachusetts regiment, although still unpaid because of a dispute over unequal wages, began to raise a sum of nearly $3,000 for a monument to Shaw and his men. The Sea Island freedpeople contributed to the effort, too. In the end, however, the planned memorial to Shaw and his men, who were buried together in the sands of Morris Island, was abandoned for fears that the shifting ground, both literal and ideological, would put the monument in jeopardy. Instead, at the behest of local donors, the money was used to fund a black school in Charleston, which, like the orphanage, was named for Shaw.38

When black Charlestonians built the Martyrs of the Race Course cemetery in April 1865, they picked up where the Sea Island freedpeople had left off. Two new black voluntary associations, the Friends of the Martyrs and the Patriotic Association of Colored Men, cleaned up the grounds and raised the graves of the more than 250 soldiers who had died there. The men also crafted a ten-foot-high, whitewashed fence that surrounded the cemetery, using lumber that they had salvaged from several nearby buildings. General John P. Hatch, Union commander in the city, had offered to secure these materials at government expense, but the black volunteers “would not yield the honor to the Quartermaster’s Department.” They also painted a “Martyrs of the Race Course” sign “by their own initiation,” according to Union physician Henry Marcy and others. All told, Redpath estimated that the black volunteers put in more than two hundred days of work, adding that they “asked and received no material recompense what ever.”39

Black Charlestonians were responsible not only for building the Martyrs of the Race Course cemetery but also for the success of the Decoration Day ceremony on May 1. African American men, women, and children constituted the bulk of the ten-thousand-person crowd that turned up at the Washington Race Course to celebrate the cemetery’s dedication. Local blacks even accounted for the military presence. When General Hatch got wind that a large contingent of black residents was headed out to the racecourse to mark the graves of the deceased prisoners, he decided to send two regiments and a military band to accompany them.40

The weather was unusually warm that spring day, the intense sun reminding Esther Hill Hawks of August. A northern physician and educator who worked with Sea Island freedpeople, Hawks joined black schoolchildren from the recently opened Morris Street School as they marched north along King Street toward the Washington Race Course. In 1822, Denmark Vesey and five fellow insurrectionists, shackled in leg irons, had been paraded past a large crowd on their way to the gallows along a similar route. The children’s procession forty-three years later was a remarkable reversal of the city’s racial politics—a reminder that the white minority’s terrifying rule was over. Although Vesey and his co-conspirators had been intentionally deprived of a proper burial, the same would not be true for the white soldiers who also died for freedom.41

Once the parade reached the Martyrs of the Race Course cemetery, the schoolchildren adorned the graves with flowers, and the rest of the procession paid their respects. Then, the parade made its way out of the cemetery, and the gate was shut, leaving just a small group of former slaves to dedicate the space. One white citizen got inside the fence, but he was ordered to leave for having recently “boasted of being a South Carolinian who would not submit to the enfranchisement of the only loyal people here.” Those gathered inside then offered prayers, read Bible passages, and sang hymns before joining the rest of the crowd at the judges’ stand. Later, the crowd listened to speeches by Union officers and prominent locals and was treated to a formal drill by the soldiers. The festivities lasted well into the evening.42

* * * *

AS WEALTHY CHARLESTONIANS made their way back into the city in the summer and fall of 1865, some found their elegant homes in tatters. Cotton broker and Confederate officer Francis J. Porcher learned that his East Battery mansion had recently been “occupied by Charles Macbeth’s plantation negroes, with their pigs & poultry.” Union soldiers had driven the freedpeople out, but a Yankee who operated a saloon on Broad Street had taken their place. The Porchers hoped to return to the house by November. Henry William DeSaussure advised his father not to return to Charleston at all. “The city is filled up with negro troops insolent & overbearing,” he wrote. “It requires great patience and self control to be able to get along.”43

Some planters were shocked to hear their former slaves criticize them for the first time, while others chafed at what William Middleton called “the utter topsy-turveying of all our institutions.” DeSaussure railed that white Charlestonians suffered the indignity of a nightly curfew—once the burden reserved for their slaves. “It is impossible to describe the condition of the city,” Henry W. Ravenel wrote fellow Charlestonian Augustin L. Taveau on June 27. “It is so unlike anything we could imagine—Negroes shoving white persons off the walk—Negro women dress in the most outré style, all with veils and parasols for which they have an especial fancy.” A couple months earlier, Ravenel had held out hope that “our institution of slavery as it existed before the war with some modifications, may be retained, & amendments to the Constitution defining the Rights of the States [adopted],” but he eventually accepted that slavery was gone for good.44

Meanwhile, Taveau published a letter in the New-York Tribune highlighting the fundamental challenge that emancipation posed to the planter worldview. “The conduct of the Negro in the late crisis of our affairs has convinced me that we were all laboring under a delusion,” he wrote. “Born and raised amid the institution, like a great many others, I believed it was necessary to our welfare, if not to our very existence. I believed that these people were content, happy and attached to their masters.” But now, thinking back over the previous few years, Taveau could not help but wonder, “If they were content, happy and attached to their masters, why did they desert him in the moment of his need and flock to an enemy whom they did not know[?]” Lowcountry planter Louis Manigault, who was a family friend of Taveau, agreed, copying Taveau’s “correct Remarks” into his journal.45

While Charleston planters’ cherished fantasies were being turned on their head, their hometown was being turned inside out. Walking the streets of the city in July, Republican Carl Schurz found African American sentinels standing guard at every public building. Whereas it once was a punishable offense to educate black children, they now filled classrooms across Charleston. In the center of the city, Schurz wrote, the Citadel—“a large castle-like building, in which the chivalric youth of South Carolina was educated for the task of perpetuating slavery by force of arms”—was occupied by the black soldiers in the Massachusetts 54th. “This is a world of compensations,” concluded Schurz. Although some elite women again shopped on King Street in the morning and walked along the Battery in the evening, others avoided the new reality. As one Charleston lady explained, “We very rarely go out, the streets are so niggery and the Yankees so numerous.”46

White Charlestonians complained, too, about the outpouring of sympathy for Union soldiers at Washington Race Course. After returning north in mid-June, James Redpath reported that the construction of the Martyrs of the Race Course cemetery “enraged the Rebels.” Local whites also lobbied to shut down the Fourth of July celebration planned by the black community. To their dismay, however, Major General Quincy A. Gillmore, commander of the Department of the South, ensured that the holiday was marked. On July 4, 1865, a large group assembled at Zion Presbyterian Church for the city’s Fourth of July ceremony. Just as Frederick Douglass had thirteen years earlier in his famous Fifth of July address, the speakers juxtaposed Independence Day ideals with the realities of chattel slavery. The Civil War had altered the meaning of the holiday for black Americans, bursting the “bands of slavery,” in the words of one orator, and allowing four million citizens to at last “bask in the sunshine of liberty.”47

One month later, black Charlestonians convened again, this time on the anniversary of emancipation in Great Britain. Since the 1830s, black communities from Massachusetts to Canada had commemorated the end of slavery in the British Empire on the first day of August. Leaping at the opportunity to celebrate West Indian emancipation for the first time, African Americans in Charleston put on an elaborate banquet, which featured a fine selection of refreshments, as well as a parade of benevolent society members outfitted in handsome regalia.48

The city’s lengthy jubilee climaxed four months later, on January 1, with a barbecue held on the anniversary of Lincoln’s 1863 Emancipation Proclamation. The year 1866 broke cloudy and damp, turning Charleston’s streets into mud. “Yet nothing could chill the ardor and enthusiasm of the occasion,” observed the South Carolina Leader, a new Republican weekly. At ten o’clock in the morning, the procession made its way north from the Battery up to Washington Race Course, where a speaker’s stand was set up not far from the Martyrs of the Race Course cemetery. The crowd of perhaps ten thousand was almost entirely black.

The program lasted from twelve until four o’clock and included numerous appeals to not lose sight of all that had changed over the last four years. Reverend Alonzo Webster, a white missionary from Vermont, evoked the harrowing journeys of runaways who were pursued deep into the New England countryside by slavery’s hounds. Freedman Samuel Dickerson said he felt like he was in a dream from which he was scared to be awakened, and General Rufus Saxton underscored the fact that the destruction of slavery had not come easily. Two years earlier, when he met with Beaufort freedpeople on New Year’s Day, 1864, “clouds and darkness seemed to hang over our country’s cause,” said Saxton. Now, not only had the Confederacy surrendered, but the U.S. Constitution had been amended to outlaw slavery once and for all. For the first time on Emancipation Day, he could proudly proclaim that “the United States of America does not recognize the right in man to hold property in human flesh.” The crowd listened attentively to the lengthy speeches. Afterward, they were rewarded with a large barbeque. “Not a single disturbance or accident of any kind occurred during the day,” concluded the South Carolina Leader, “and all went ‘merry as a marriage bell.’”49

* * * *

THE SUCCESS OF Charleston’s first Emancipation Day, like most festivals of freedom over the preceding year, did not mean that former Confederates had come to terms with such demonstrations and all they represented. According to one source, who recounted white reactions to the Emancipation Day celebration, “the citizens generally, and the late nigger drivers in particular, sneered most profoundly at the whole affair.” They whispered that “the police were going to interfere and quash the whole matter; but on counting noses, and calculating consequences, the project was prudently abandoned.”50

Ex-Confederates compensated by complaining. Jacob F. Schirmer, a prominent Charleston native, scribbled in his journal that the freedpeople returned from the Emancipation Day festivities drunk from consuming copious quantities of liquor. And the Charleston Daily News parodied the New Year’s Day event in a column dripping with sarcasm. It was “a day of jubilee—a JUBILEE JUBILORUM—a one-sided game of chequers, in which the black men were all kings, and the white all privates, except a few, who, having gotten into the enemy’s ‘back line,’ deserted their colors, and were crowned as black kings.” The parade consisted of “lordly knights” with “coal-black masks” and “a long row of darkey civilians, wearing each a badge.” These were not the “old copper badges, which, in the good old times, or perhaps they may prefer the expression the bad old times—old masters was wont to purchase” for them, “but a badge of honor, a small piece of ribbon, which cost little or nothing, and for which they themselves had paid handsomely.” Having traded their slave badges for worthless replacements, snickered the Daily News correspondent, they merrily marched on, “indiscriminately mixed up, without regard to size; tall niggers with low hats walked with short niggers with tall hats—some sported umbrellas, some walking canes.”

The correspondent was equally galled by what he saw at the Washington Race Course. “The old Jockey Club House, where in days of yore the beauty and fashion of Carolina were wont to congregate now filled with negro men and negro women!” Although little troubled by the words of the black participants, he was sickened by what their white counterparts had to say. “One would-be orator made a speech,” wrote the correspondent breathlessly, “in which he first bragged about being a Vermonter, then tried to stir up the negroes by insidious remarks, calculated to make their thoughts revert to the days of their slavery.”51

Charleston was an altogether different place at the dawn of 1866 than it had been eleven months earlier. Slavery and the Confederacy were dead and buried, and their apologists—outnumbered and outgunned—could do little more than carp about these changes and ridicule those who championed them. In the years that followed, the battle over the memory of slavery would grow more pitched, as whites and blacks confronted the great task before them—how to reconstruct their city, state, and nation.