Reconstructing Charleston in the Shadow of Slavery

TWO YEARS AFTER CHARLESTON FREEDPEOPLE CONCLUDED their extended wake for slavery, an astonishing meeting convened in the city. The purpose: to stamp out the last vestiges of the peculiar institution. On a windy and rainy January afternoon in 1868, 121 delegates to the state’s constitutional convention gathered in the elegant Charleston Club House on Meeting Street, just south of Broad. Seventy-two of the men who came to redraft the South Carolina constitution were African American, and forty-one had once been slaves. For the first time in history, South Carolina’s black majority would have a voice in the state’s future.1

An hour before the opening session on January 14, black Charlestonians had begun lining the sidewalk across from the Club House. Others wandered through the building’s handsome grounds. When the doors to the hall opened around noon, the black crowd rushed inside. Few whites joined them.2

While African Americans thrilled at the opportunity to witness history in the making, white South Carolinians fretted about the revolutionary developments under way. “Our Black and Tan members have gone to Charleston to meet in Convention on tomorrow,” wrote a Spartanburg planter in his journal on January 13. “There the negroes are to make laws to rule white people. For bid it, Fates.” The next day, the Charleston Daily News remarked, “To-day marks the commencement of a new and sad era in our history. The Carolina of old—with her peace, her prosperity and her freedom—is, for the present, dead.”3

Charleston Mercury editor Robert B. Rhett Jr. and his brother Edmund were struck by the contrast between the gentlemen who had built the Charleston Club House and the diverse collection that assembled there on that January afternoon. Noting the blustery weather that rattled the windows during much of the first day’s proceedings, they ventured that “it would have taken but a slight stretch of a superstitious imagination, to fancy that the ghosts of the departed Carolinians . . . had risen from their graves, and come to enter their protest against the awful desecration.” To make matters worse, the Rhetts vented, one black delegate had the audacity to dress entirely in gray, an affront to Confederate veterans everywhere.4

For Confederate stalwarts like the Rhetts, the memory of slavery cast a long shadow over the 1868 constitutional convention. Predictably, the Charleston brothers played up the antebellum status of the delegates to what they dubbed “the Great Ringed-Streaked and Striped Negro Convention” in their firebrand newspaper, which they had revived in 1866. The Mercury, which claimed the largest circulation in the city, ran a monthlong series of mostly critical portraits for its conservative readership. The Rhetts mocked ex-slave delegates’ vocabulary, grammar, morals, and behavior, comparing some African American participants to baboons and orangutans.5

The convention delegates themselves—almost all of whom counted themselves Republicans—also refracted the gathering through the prism of slavery, albeit from a different angle. On January 15, convention president Albert G. Mackey, a white Unionist physician from Charleston, noted that the meeting was the first constitutional convention in state history untainted by the stain of slavery. Previous conventions had prevented many South Carolinians from exercising “the elective franchise, because slavery, that vile relic of barbarism, had thrown its blighting influence upon the minds of the people.” While ex-Confederates denounced the 1868 convention as being representative of everything that had gone wrong over the past few years, Mackey and his fellow Republicans—black and white alike—viewed the 121 delegates as the embodiment of what was possible in a South Carolina that had rid itself of slavery and all that went along with it.6

The Civil War may have broken the yoke of bondage, but it could hardly erase the memory of the institution. The wounds of having once been counted as property—of having been beaten, raped, or sold away from loved ones—were still fresh for countless black southerners. So, too, was the sense of betrayal that many white southerners felt when they learned that the enslaved were not the happy, devoted servants they had imagined them to be. The ghosts of the enslaved past were especially haunting in Charleston, where just about every resident had a firsthand familiarity with slavery. Throughout the next decade, as Republicans and Democrats struggled for political supremacy across the city, state, and the rest of the Reconstruction South, these memories—positive and negative, real and imagined—surfaced over and over.

* * * *

BY THE MIDDLE of 1865, most white South Carolinians had made their peace with the reality that they were, as Emma Holmes put it, “a conquered people.” Following President Andrew Johnson’s directive, Unionists and Confederates took the oath of allegiance, pledging to support not only the United States and its laws but also all wartime proclamations regarding emancipation. When a Charleston delegation visited Johnson in Washington, D.C., that summer, the new president told them that though slavery had been destroyed by war, it would be best if it were also ended by law. Hoping to bring military occupation to a swift end, the delegation heeded Johnson’s advice. In September, a state constitutional convention—the last all-white meeting of its kind—admitted that slavery, having been destroyed by the United States government, would not be reestablished in South Carolina. The following month, in accordance with Johnson’s restoration plan, a special session of the state General Assembly ratified the Thirteenth Amendment, which abolished slavery. The institution that had brought great wealth to a few South Carolinians and suffering to so many was over.7

Still, in the months that followed, the state’s white citizenry worked to limit the social and economic effects of emancipation by passing the Black Codes. These measures gave freedpeople some new rights and liberties. They could now make contracts, buy and sell property, and sue or be sued. But the Black Codes, like similar statutes passed across the South, also delineated legal constraints that applied solely to African Americans. South Carolina limited blacks’ rights of travel and gun ownership, charged black tradesmen significant license fees, and created a separate district court system for African Americans. Black children as young as two could be apprenticed out to masters, while judicial officers were given the power to whip adult servants and return runaway servants to their employers.8

Provisional governor Benjamin F. Perry justified the Black Codes using a paternalistic logic rooted in the culture of the Old South. Positing former slaves as children in need of protection not only from the outside world but also from themselves, he argued that the new laws provided essential safeguards. As Edmund Rhett wrote in October 1865, “the general interest of both the white man and the negro requires that he should be kept . . . as near to the condition of slavery as possible.” Slavery was dead and buried, but its specter still hung over South Carolina.9

Little wonder, then, that opponents of the Black Codes also turned to remembrances of slavery as they made their case against the offensive measures—and others like them. The South Carolina Leader, a Republican newspaper founded in Charleston by several printers from a Pennsylvania regiment, took direct aim at the Black Codes. The new laws, insisted the weekly’s white editors on December 16, were little more than an expression of the “average of the justice and humanity which the late slaveholders possess.” In the same issue, the paper ran a column from the Boston Journal that ridiculed the Black Codes as evidence that South Carolina had given up slavery in name but hoped to retain it in fact. And when planters in Bennettsville, near the North Carolina border, drafted a set of resolutions about contracting with and disciplining freedpeople on the first Monday in December, the South Carolina Leader reminded readers of the doleful meaning the day had for black South Carolinians. Before the war, counties had staged sale days on the first Monday of every month, during which town squares were transformed into open markets for the auctioning of all sorts of property, including slaves. But no more. This “is a day which will never again be the occasion of divorcing husband from wife and separating children from parents—a day which never again will witness the sale of ‘female domestics guaranteed’ to the highest bidder,” maintained the Leader. Yet the resolutions adopted in Bennettsville, which required freedpeople to gain permission to find a new employer and asserted the right of planters to discipline their workers, were a troubling reminder that planters still fancied themselves “lord[s] of the manor.”10

Palmetto State planters, however, struggled to reassert their lordly status, at least in the short run. Indeed, just weeks after the General Assembly began passing the Black Codes, General Daniel E. Sickles, the military commander of South Carolina, declared them null and void. Nevertheless, the South Carolina Leader determined to keep memories of slavery and the Civil War fresh in the minds of its readers, if only to delegitimize further efforts to circumscribe black rights. In early 1866 the Leader began publishing a column called “Secession Gleams,” reprinting extracts from southern writing produced during the conflict. The January 6 edition included a sermon that was first delivered in Yorkville, South Carolina, in 1861, in the wake of the Confederate victory at the First Battle of Bull Run. “The eminence of the South,” John T. Wightman had proclaimed, “is the result of her domestic slavery, the feature which gives character to her history and which marshals the mighty events now at work for her defence [sic] and perpetuity.” A week later, the Republican weekly reproduced an 1861 letter written by L.W. Spratt. In it, the South Carolina fire-eater argued that the Confederacy, founded as “a Slave Republic,” should “own slavery as the source” of its authority by repealing its ban on the transatlantic slave trade.11

Ex-Confederates were less eager to remind South Carolinians about the secessionist past, especially with the Union Army still present in the state. Yet they could hardly forget slavery with the consequences of its demise all around them. More than a year after the end of the war, Charleston remained a wreck—worse than even Richmond or Columbia, according to a New York Times correspondent, who described “the tall, towering chimneys, standing alone amid flowering shrubbery, and neglected but beautiful gardens; the broken marble slabs and pieces of statuary that lay amid the waving grass of elegant lawns.”12

To most former Confederates, the state’s political fortunes were equally grim. White South Carolinians fumed over Republicans’ refusal to seat southern congressional delegations in Washington, D.C., as well as the passage of the Civil Rights Act, which outlawed discriminatory statutes like the Black Codes. To make matters worse, with the Military Reconstruction Acts of 1867, Republicans in Congress paved the way for black male suffrage in the South. The prospect of living under a “negro constitution” and watching African American men vote and serve in political office led Robert and Edmund Rhett to denounce emancipation, nearly three years after Appomattox. “We did not and do not believe that the negro is fit to be free, and not being fit to be free, we do not believe that he is fit to vote,” they announced in the Charleston Mercury on April 2, 1868. “We do not believe that all men have, or ever will have, or even ought to have equal rights. We, therefore, believe that slavery was justified—not only justified, but in the highest degree humane.”13

Many white South Carolinians agreed that slavery had been a righteous institution, but few of them followed the Rhetts in publicly framing emancipation as a mistake. More often, ex-Confederates accepted that slavery was gone for good. In the fall of 1866, Confederate general Wade Hampton III clarified his position on abolition before a group of his former soldiers. Although Hampton objected to the means by which the North had secured the end of slavery—excluding rebel states from the Union until they ratified the Thirteenth Amendment—he consented to the result. “The deed has been done, and, I for one, do honestly declare that I never wish to see it revoked,” he stated.14

This did not mean, however, that Hampton repudiated slavery itself. On the contrary, the Charleston native—a wealthy planter who had owned hundreds of slaves before the war—regaled the civilizing influence of the peculiar institution on the slave. “Under our paternal care, from a mere handful he grew to be a mighty host,” Hampton told his fellow veterans in October 1866. “He came to us a heathen, we made him a Christian. Idle, vicious, savage in his own country; in ours he became industrious, gentle, civilized.”15

The following March, in response to Congress’s decision to extend the vote to southern black men, Hampton pitched this paternalistic message to a group of freedpeople in the state capital. In a speech that was widely covered across the country, he appealed to soon-to-be-enfranchised Columbians on the basis of the benevolent record of slaveholders like him. “I hope that as my past conduct to you has made you look upon me as your friend, so my advice and actions in the future will but confirm you in that belief,” Hampton said. “How will you vote?” he then asked his black audience. “Will you choose men who are ignorant of all law—all science of Government, to make your laws and to frame your Government? Will you place in office these strangers who have flocked here to plunder what little is left to us? Or will you trust the men amongst whom you have lived heretofore—amongst whom you must always live?” Having dismissed former slaves and northern carpetbaggers as unfit for government office, Hampton insisted that the third course was the most prudent, for it was in southern whites’ interest to ensure that African Americans were prosperous and content.16

Charleston’s conservative press cheered Hampton’s plea. The Daily News pronounced his speech to be representative of the convictions of most white southerners. The Charleston Courier, which after a short stint as a Unionist paper had returned to local, conservative hands in late 1865, reproduced the general’s address in full. Echoing Hampton’s sentiments, Courier editor and Confederate veteran Thomas Y. Simons insisted that white South Carolinians had readily embraced emancipation once the war ended. Like many of his brethren, Simons doubted the wisdom of giving African American men the ballot. But now he simply hoped every citizen of the state would exercise the vote judiciously. The editor was particularly frustrated by the deep well of moral capital that emancipation provided the Republican Party. “The truth is, that the freedom of the late slaves did not spring from any sentiment of real philanthropy on the part of the North,” argued Simons. Instead, Republicans embraced emancipation only when the Union Army became desperate for more recruits. Simons urged black South Carolinians not to be swayed by Republican propaganda but rather to put their trust in “their reliable friends” around them. This particular friend did not remind his readers that before the war he had told the South Carolina legislature that the election of a “Black Republican” to the presidency presented a mortal threat to slavery.17

Unsurprisingly, South Carolina Republicans took issue with such appeals. The Charleston Advocate, a new Republican weekly, insisted that Wade Hampton and his fellow planters “held the colored man in brutal slavery, and sold him as a dumb brute in the shambles.” How “dare they to refer to slavery, and set themselves up as the colored man’s best friends in whom he should confide.” Francis L. Cardozo, a freeborn black Charlestonian who had left for Scotland as a young man but returned during Reconstruction, also dismissed the idea. “Who advocated and laid down millions of treasure and thousands of lives to maintain this great wrong [of slavery] and oppression to our people?” he asked a large crowd that assembled at Military Hall three days after Hampton’s March address. “Who but the Southern whites, who now pretend to be our best friends, and claim our united action with them.”18

* * * *

JUDGING BY THE election that fall, South Carolina’s black majority put little stock in Hampton’s and other planters’ attempts to curry favor. In late November 1867, ex-slaves turned out en masse to vote for the proposed state constitutional convention, trumping a conservative plan to boycott the election and thereby block the convention by denying it the requisite level of participation. What’s more, they elected a slate of delegates that included only a handful of former masters.19

Two months later, on January 14, 1868, the South Carolina Constitutional Convention convened at the Charleston Club House. Technically, the Reconstruction Acts required that they draft a document that fully conformed to the U.S. Constitution and gave the vote to both black and white men. But the interracial group of delegates who assembled in Charleston on that rainy day understood their task as something far greater. “It is our duty,” announced Beaufort delegate J.J. Wright, a Pennsylvania-born black, “to destroy all the elements of the institution of slavery.”20

Chief among such elements was South Carolina’s uniquely undemocratic political culture. Fears of servile insurrection had undermined political dissent in the state and, as a result, inhibited the establishment of a legitimate two-party system. And while most states in the antebellum period held popular elections for president and governor, South Carolina left those choices (and a host of others) up to its legislature. By means of malapportionment, formidable property qualifications for voting, and even higher qualifications for officeholding, Lowcountry rice planters and Upcountry cotton planters had long dominated the General Assembly.21

From the start, convention delegates made it clear that they planned to dismantle South Carolina’s undemocratic system rather than reap its benefits. They cut back significantly on the power of the General Assembly and ensured that the state would popularly elect presidential electors as well as the governor. The convention also eliminated property ownership qualifications for serving in the legislature and stipulated that wealth would not be a factor in determining representation in its lower house. Finally, the new constitution provided for universal manhood suffrage.22

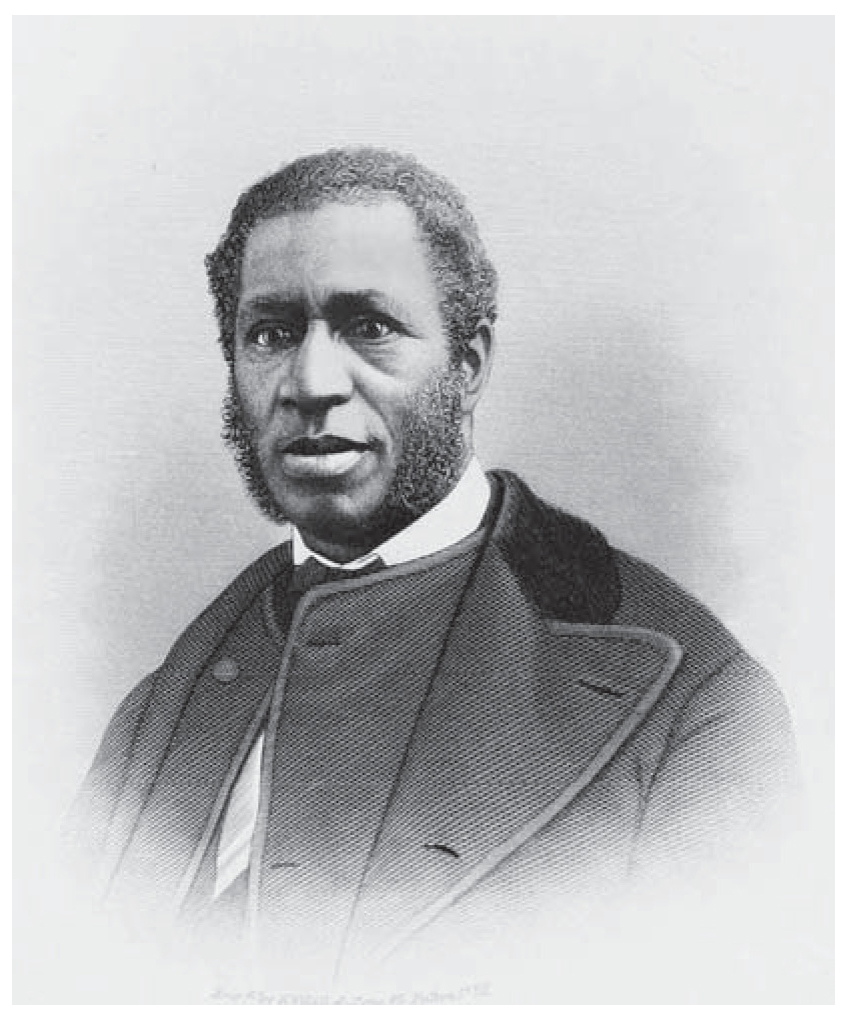

Richard “Daddy” Cain moved to Charleston in 1865 to help resurrect its African Methodist Episcopal church. He was also a delegate to the 1868 South Carolina Constitutional Convention.

Early on, a few delegates tried to restrict suffrage rights to those who could read and write. Yet several others strenuously objected to this provision, highlighting the blind eye that it turned toward the educational constraints placed upon South Carolina slaves. Literacy restrictions, Virginia-born minister Richard H. Cain told his fellow delegates, were an antebellum holdover inconsistent with the new era of progress. “Daddy” Cain, as his parishioners admiringly called him, had come to Charleston in the spring of 1865 to help reestablish the African Methodist Episcopal congregation, four decades after its church building had been destroyed. A short, charismatic man with a powerful voice, Cain built the new Emanuel A.M.E. Church, whose sanctuary was designed by Denmark Vesey’s son Robert, into a large, influential congregation. “In this Constitution,” Cain reasoned at the 1868 convention, “we do not wish to leave a jot or title upon which anything can be built to remind our children of their former state of slavery.” Such arguments helped convince the convention to vote in near unanimity not to include this remnant of the peculiar institution in the new constitution.23

Recollections of slavery shaped convention debates over debtor relief, too. Delegates who wanted to punish slave dealers, for instance, introduced an ordinance to negate all debts incurred through the purchase of slaves. Some opponents of this measure insisted that contracts from slave sales were the same as any other contracts and should be respected as such. Others made explicitly antislavery arguments against the proposed ordinance. Simeon Corley, a white delegate from Lexington, questioned the legitimacy of a measure that appeared to treat those who sold slaves as more culpable than those who bought them. “Is there any difference between the seller and buyer in a moral sense?” he asked.24

Most of Corley’s fellow delegates thought there was. “I regard the seller of the slave as the principal, and the buyer as the accessory,” pronounced African American delegate Robert Elliott. “A few years ago the popular verdict of this country was passed upon the slave seller and the slave buyer, and both were found guilty of the enormous crime of slavery. The buyer of the slave received his sentence, which was the loss of the slave, and we are now to pass sentence upon the seller. We propose that he shall be punished by the loss of his money.” Several of Elliott’s allies singled out professional slave traders as particularly unworthy of sympathy. “Many of these men to whom these debts are due, are those who trafficked in slaves and came from all parts of the United States,” insisted J.J. Wright. “They came from the Northeast and the West . . . with vessels bringing in a cargo of slaves, sold them to the people of the South, put what money they could in their pockets, and went back where they belonged.”25

Wright’s comments reveal a curious feature of this debate. By placing most of the blame for the peculiar institution on the shoulders of slave traders, supporters of the measure seemed to want to absolve South Carolina, in particular, and the South, more generally, of the sin of slavery. William J. Whipper, a Pennsylvania-born black delegate who also represented Beaufort, went further than Wright in defending his adopted state. “Be it said to the eternal honor of South Carolina, she opposed the institution, and it was not until a renegade dog forced the bone upon her, and made it into dollars and cents, that she consented,” concluded Whipper. The black delegate thereby anticipated an argument that in the decades that followed would become a staple of the Lost Cause liturgy.26

Other supporters of the ordinance to forgive slave-sale debt focused on the broader message that it would send across the globe. Freeborn Charlestonian Alonzo J. Ransier supported the proposed mea sure because he could not condone the recognition of human chattel. Daniel H. Chamberlain, a Massachusetts native and future governor of the state, agreed. He viewed the ordinance as the natural by-product of northern victory in the Civil War: “The confederacy fell, and with it fell slavery; with it fell property in man; with it fell every claim and every obligation which rested on the basis of slavery.” Shortly after Chamberlain spoke, the convention members overwhelmingly voted to have their state’s new constitution invalidate debts contracted for the purchase of slaves.27

Memories of slavery also fueled white conservatives’ objections to the convention proceedings. “Can there be anything more abhorrent to the feelings of an honorable man,” wondered former governor Benjamin F. Perry, “than to see these renegades & adventurers, black & white, from all the northern states coming here associating with our former slaves and the vilest of the white race in order to form organic laws for the gentlemen of South Carolina?” Robert and Edmund Rhett did not think so. They kept up a steady drumbeat against the convention in the pages of the Charleston Mercury, ridiculing the proceedings and satirizing its delegates. So offensive was the paper’s early coverage that the convention briefly considered banning the Charleston Mercury’s reporter from the Charleston Club House.28

Seething over the idea that their former field hands and domestics were being allowed to write the state’s constitution, the Rhett brothers painted portraits of black delegates that emphasized their enslaved pasts. The Mercury described Sumter representative Samuel Lee as “an excellent house servant . . . [who] understands waiting on table, to which he has been trained” and characterized Greenville delegate Wilson Cook as respectable and compliant, despite “his ambition to attend public meetings and make speeches.” Even freeborn black delegates evoked slavery for the Rhetts. Their paper represented Pennsylvanian William J. Whipper as “a genuine negro, black and kinky headed, who, in the days of slavery, would have been esteemed a likely fellow for a house servant or a coachman.”29

Certain memories provided a ray of hope for defenders of the planter class. Of Abbeville’s Hutson J. Lomax, the Mercury proclaimed: “He was a well behaved servant, and, as he grew up, he was allowed by his master to learn the trade of a carpenter. . . . He was a faithful slave during the late war, and did not appear to undergo any great change in consequence of the ‘emancipation’ proclamation.” But any hope that men like Lomax might demonstrate the same fidelity in freedom as they appeared to have shown in chains did not last long. “The grand purpose of the negro constitution is to set up and establish negro rule in South Carolina,” concluded the Mercury after the convention closed in March 1868.30

Later that year, ex-Confederates watched in horror as the state’s black majority ratified the new, racially egalitarian constitution and elected a slew of black and white Republicans to local, state, and national offices. In Charleston, voters chose Gilbert Pillsbury, a Massachusetts abolitionist who had come to the state to work for the Freedmen’s Bureau, as mayor and a full slate of Republicans as aldermen. At the state level, white Ohioan Robert K. Scott was elected governor, and Republicans won large majorities in both houses of the General Assembly. Remarkably, 60 percent of the new lower house was black.31

As Republicans assumed political power across the state that fall, the South’s most infamous conservative newspaper folded once again. Unable to pay its bills, the Rhetts stopped publishing the Mercury in October and subsequently printed a broadside bidding farewell to their subscribers. Although distraught about the new regime that had elevated inferior blacks over civilized whites, Robert Barnwell Rhett Sr., who penned the valediction under his son Robert’s name, remained defiant. He maintained that the southern people would neither forgive nor forget. “The negro serves a purpose for Southern Independence far greater than his numbers or presence tells against it,” he stated. “There is no ground of forgetfulness—no possibility of forgiveness, with these black, moving memorials of our wrongs, polluting our sight.”32

* * * *

WHILE WHITE CONSERVATIVES like the Rhetts stewed, Republicans enjoyed the fruits of political empowerment. The Union Army occupation of the city between 1865 and 1868 and the Republican Party’s control of local and state government for much of the decade that followed ensured that former slaves and their allies had a prominent voice. After a three-year hiatus, Charleston Unionists resumed their Decoration Day ceremonies in 1868, though not at the Martyrs of the Race Course cemetery. The Union burial ground had fallen into disrepair, and eventually the remains of the prisoners who died there were removed to a federal cemetery in Beaufort. The May 30, 1868, ceremony, marked according to the directions of the Grand Army of the Republic (GAR), the North’s veterans association, was held at Military Hall. A crowd of fifty or so white Unionists gathered at the Gothic structure on Wentworth Street for the service. The Civil War, insisted New York colonel A.J. Willard, had been the tragic result of the South’s “perverted” institution of slavery, which checked the progress of civil rights and universal suffrage.33

Black Charlestonians played a bigger role in later Decoration Day services, which were held at Magnolia Cemetery, where some Union dead had been interred. Organized by the Robert Gould Shaw Post No. 1 of the GAR and a committee of Unionist ladies, the May 1869 ceremony boasted a crowd of more than two thousand people, most of whom were African American. The orations that day included a speech by black state representative Alonzo J. Ransier. One year later, a large, mostly African American crowd assembled around a flag-draped stand, upon which sat former Union officers as well as black and white officeholders, including William J. Whipper, who, like Ransier, moved into the legislature after serving as a constitutional convention delegate.34

Slavery continued to be a prominent topic at these integrated services. At the 1870 Decoration Day ceremony, General William Gurney, who had relocated from New York to Charleston after the war, underscored the institution’s centrality to the Civil War. He acknowledged the sacrifices of soldiers on both sides of the conflict, but Gurney insisted that Union men had given their lives to destroy human bondage, while Confederates had gone to war for an outdated and effete idea. Whipper, too, balanced a tribute to Confederate bravery with a clear statement about the superiority of the Union cause. One side fought “for liberty, which was brought over in the ship which landed its living freight on Plymouth Rock; the other for the maintenance of an oppression which was brought to this country in a low black schooner which sailed upon the James River in 1620.”35

By the early 1870s, the remains of most Union soldiers in Charleston had been removed to national cemeteries in Beaufort and Florence, undercutting Decoration Day ceremonies in the city. But local African Americans and Unionists still marked the end of slavery on Emancipation Day (January 1), Independence Day (July 4), and three or four other annual freedom festivals, just as they had since 1865.36

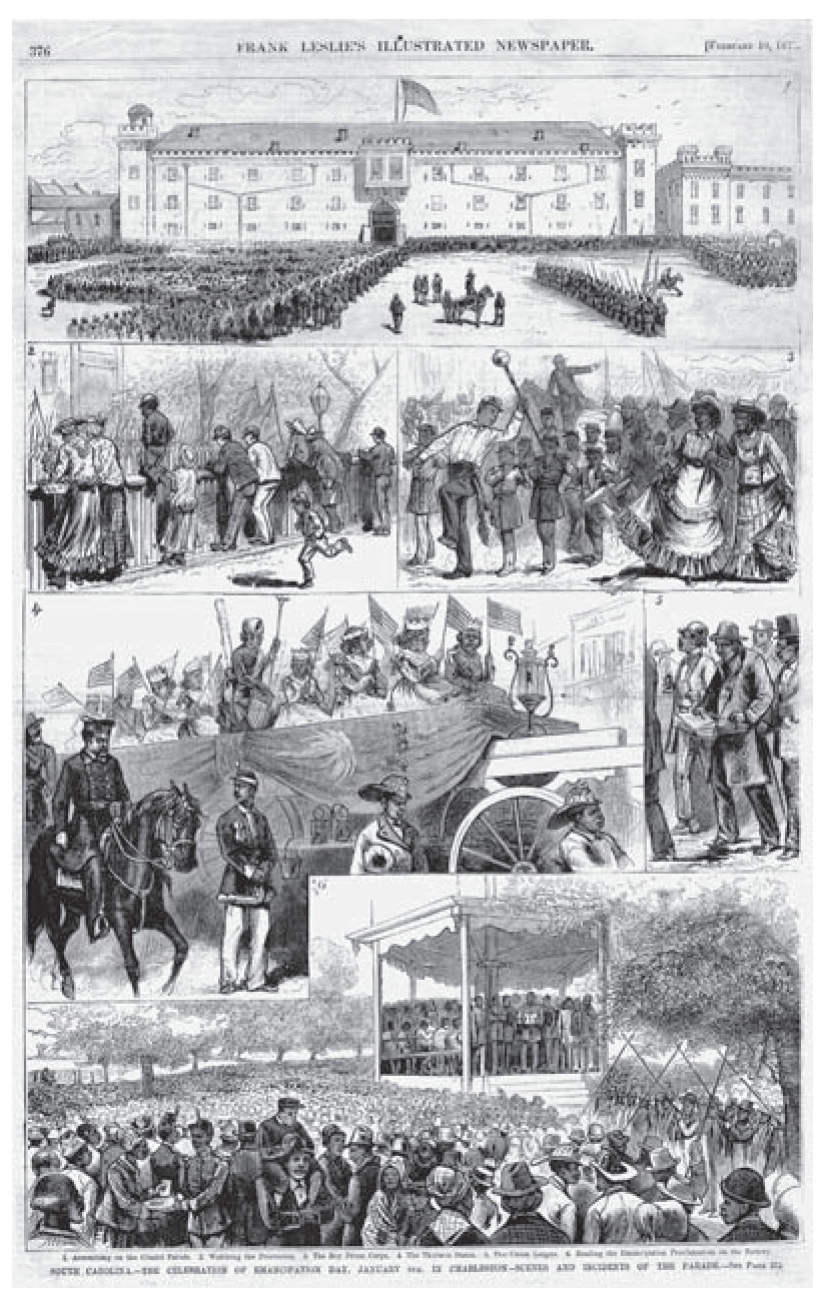

“South Carolina—The Celebration of Emancipation Day, January 8th in Charleston—Scenes and Incidents of the Parade.” From Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, February 10, 1877.

The parades accompanying these celebrations followed routes carefully plotted to dramatize freedpeople’s newfound status. The Emancipation Day procession on January 2, 1871, for instance, commenced at the Citadel Green, marched north up Meeting Street, west on John Street, and then south along King Street. In a symbolic statement that few could have missed, the route took the armed black procession around not just the Citadel Green, but also the military academy that the defenders of slavery had long called home. The parade then moved south on King Street, east on Hasell Street, and then south again along Meeting, where it passed directly west of the city’s slave-trading district. The parade ended at White Point Garden at the Battery, where African Americans had been prohibited from gathering from the 1840s until the end of the Civil War.37

Charleston’s freedom pageants became larger, more elaborate, and more political in the 1870s. “The entire state government” came to town on Emancipation Day in 1874, sneered the Charleston News and Courier, “from the Governor to the thousand and one pages who draw three dollars per diem during the session of the Legislature.” By that point, black militia companies from Charleston and neighboring towns were a conspicuous feature on Emancipation Day and the Fourth of July. Each holiday, thousands of Lowcountry African Americans lined up early to watch their armed brethren, many decked out in the dark blue uniforms of the state militia, march in orderly fashion through city streets. These martial displays intertwined past and present. Led by mounted officers, including ex-slaves Robert Smalls and Samuel Dickerson, the black companies were often named for abolitionists and other black heroes. The 1876 Fourth of July parade included the Lincoln Rifle Guard, the Attucks Light Infantry, the Douglass Light Infantry, the Delany Light Infantry, and the Garrison Light Infantry. The sight of former slaves carrying muskets with bayonets and unsheathed swords no doubt inspired pride in the black crowd and fear in the few whites who ventured out to watch. But the processions were also a practical reminder of the military force that kept at bay the white paramilitary groups, including the Ku Klux Klan and hundreds of rifle and sabre clubs, hoping to end Republican rule in the South and return white supremacist Democrats to power.38

The parades typically ended at the Battery, where enormous crowds bought peanuts, cakes, fried fish, and sassafras beer from vendors camped out in shady spots in White Point Garden. The scene was especially festive on the Fourth of July. “The whole colored population seemed to have turned out into the open air,” reported the Daily News on July 5, 1872, “and the gardens were so densely thronged that it was only with the utmost difficulty that locomotion was possible amid the booths, stalls and sightseers.”39

Still, the black men and women who congregated along the Battery and in White Point Garden on the Fourth—many of whom had come in from the Sea Islands—found space to perform ring dances from dawn to dusk. In form, the dances resembled the ring shout, in which enslaved men and women had danced in a circle, stomping their feet, clapping their hands, and singing in a call-and-response fashion. In substance, these Fourth of July rituals drew on a second enslaved tradition—mocking the formal manners and customs of the planter class in song and dance. Postbellum ring dances provided Charleston’s freedpeople a chance to poke fun at elite courtship rituals as they celebrated their emancipation. The rituals also afforded black women, largely excluded from the parades and speakers’ platforms, a public role in Charleston’s festivals of freedom. In 1876, the News and Courier described the “Toola-loo,” a popular new ring song and dance that became a staple of later commemorations. About two dozen participants—evenly split between men and women—formed a ring, into which one of the female dancers would move while the others began to sing and clap. “Go hunt your lover, Too-la-loo!/Go find your lover, Too-la-loo!” they urged the lady in the center, who eventually chose one man to join her in the ring. While hundreds of revelers danced the Too-la-loo in 1876, hundreds more gathered around the White Point Garden music stand to listen to speeches. Among the most well-attended orations that afternoon, grumbled the News and Courier, was the “rambling political harangue” delivered by “Daddy” Cain.40

An 1851 view of the lower peninsula showing the Battery and White Point Garden, which played host to annual Emancipation Day and Fourth of July celebrations after the Civil War.

Many of the addresses delivered as a part of prior Fourth of July and Emancipation Day celebrations had been similarly political. Speakers at these events often used references to slavery to promote black and Republican candidates for office. At the 1870 Fourth of July commemoration at White Point Garden, Martin R. Delany warned black Charlestonians not to trust white politicians but rather to support black leaders like him lest they find themselves back in chains. The following year, Samuel Dickerson lauded Republican principles and the party’s role in destroying slavery. To the dismay of the Daily News, the freedman’s Emancipation Day address brought in “much inflammatory matter by a comparison between the present and former condition of the colored people in this state.”41

Such memories, no doubt, were painful to many South Carolina freedpeople. After black abolitionist Frances Ellen Watkins Harper toured the state in 1867, she wrote, “The South is a sad place, it is so rife with mournful memories and sad revelations of the past. Here you listen to heart-saddening stories of grievous old wrongs, for the shadows of the past have not been fully lifted from the minds of the former victims of slavery.” However distressing, Charleston’s black community refused to let locals forget about its enslaved past. And if a freedperson wanted a permanent memento, she could pay $2.50 for a “magnificent” copy of the Emancipation Proclamation, which were advertised for sale in the Charleston Courier.42

* * * *

ALTHOUGH WHITE CHARLESTONIANS were not above making money by helping to hawk emancipationist mementos, they endlessly carped about black festivals of freedom. Nathaniel Russell Middleton told his daughter that the Fourth was “a dreadful day” for white Charlestonians that would “not have been permitted in a civilized community.” While white citizens “showed proper respect for the day by the suspension of all business,” noted the Daily News in 1866, black residents put on an extravagant Fourth of July celebration. “Childlike, he loves a holiday,” the paper complained of the typical freedman.43

Some members of Charleston’s African American elite—concerned about maintaining social distance from former slaves—were also frustrated by such displays. On the eve of Emancipation Day in 1867, the New York Times reported that freeborn black Charlestonians “look coldly upon this demonstration of their more recently emancipated brethren, for whom they take no pains to conceal their contempt.” But it was white residents who complained the loudest. In 1869, Charleston Courier editor Thomas Y. Simons smarted that what had once been a day for the white citizenry to shoot off their rusty muskets and drink mint juleps had become a day for African American revelry. Using a name intended to evoke African Americans’ formerly servile status, he wrote that “Cuffee takes the place of the former celebrants of the day. . . . Cuffee shoulders the time-honored flint muskets of the beats.”44

Prominent merchant Jacob F. Schirmer was the city’s most consistent and vitriolic critic of these black celebrations, though he confined his complaints to his journal. In 1866 Schirmer lamented that the nation’s holiday had become “a nigger day”: “Nigger procession[,] nigger dinner and balls and promenades,” and “scarcely a white person seen in the streets.” One year later, he called the Fourth “the Day the Niggers now celebrate, and the whites stay home and work.” Schirmer struggled to find the words to describe what took place at White Point Garden under the blazing hot sun of July 4, 1872. “All of the African race” seemed to have come out for the festivities.45

White Charlestonians also staged commemorations of their own. In the spring of 1866, a group of women determined to shower local Confederates with the same affection that the city’s black citizenry had bestowed upon the Union soldiers buried in the Martyrs of the Race Course cemetery one year earlier. To this end, they formed the Ladies’ Memorial Association of Charleston (LMAC), which, like similar groups founded in Richmond, Vicksburg, and Augusta, drew its supporters mainly from middle-class and elite circles. The LMAC sponsored the region’s first Confederate Decoration Day ceremony, which was held on June 16, 1866, the anniversary of the nearby Battle of Secessionville. It seemed like the Sabbath in Charleston that day, with most stores closing before noon and churches across the city holding services. Confederate graves in the downtown area were decorated with flowers, and, despite heavy rains, men, women, and children packed carriages and train cars for the two-mile ride up to Magnolia Cemetery.

The solemn afternoon ceremonies took place on a makeshift stage erected next to the burial ground. The lead orator for the service was John L. Girardeau, a white Confederate chaplain who before the war had been the minister for Zion Presbyterian Church’s large black congregation. “We are here as mourners to-day,” he reminded the predominantly female crowd. “Simply retrospective in its character, it has no covert political complexion, and no latent and insidious reference to the future.” In contrast to later Confederate Decoration Day ceremonies, this first event largely steered clear of anything that might be perceived as controversial or sectionally divisive.46

That fall, the LMAC was joined by the Survivors’ Association of Charleston (SAC), one of the nation’s first Confederate veterans organizations. The SAC also found support among city bluebloods, including members of the Gaillard, Manigault, and Rutledge families, who proclaimed it their duty to assist impoverished veterans as well as Confederate widows and orphans. Strident ex-Confederates Cornelius Irvine Walker and Edward McCrady Jr. were among the founding members of the SAC, yet the group initially focused its attention on nonpartisan activities, such as encouraging medical assistance to the wounded, securing jobs for the destitute, and documenting individuals who had fought for the Confederacy. In the short run, the Survivors took a back seat when it came to public commemorations, ceding control to their female counterparts in the LMAC, who, following Victorian mores, were assumed to be apolitical and thus no threat to sectional reunion.47

For the next several years, the city’s Confederate memorial demonstrations were as staid as the original Confederate Decoration Day. The presence of the Union Army, as well as the advent of black political power, kept partisan displays in check. Following General Daniel E. Sickles’s December 1866 order that Confederate memorial organizations should confine themselves to charity and memorial services, the LMAC concentrated on establishing the Home for the Mothers, Widows, and Daughters of Confederate Soldiers on Broad Street, installing Confederate headstones, and quietly decorating graves at Magnolia.48

In the early 1870s, however, the LMAC began sponsoring more elaborate Decoration Day events, which featured spirited addresses by ex-Confederates. Meanwhile, former rebel soldiers flocked to join veterans organizations, such as the SAC, which gained a wider influence in 1869, when it expanded into the statewide Survivors’ Association of South Carolina (SASC). As it grew, the SASC added a second objective to its philanthropic work: honoring “the dead and the principles for which they sacrificed their lives, by collecting and preserving facts for a full and impartial history” of the war. It was the duty of all veterans who survived the war to ensure that the Confederate cause “should not be forgotten, or suffered to be distorted or misrepresented by their enemies,” wrote one veteran to Edward McCrady, chairman of the SASC executive committee, in 1871. Under the influence of the SASC and the LMAC, Charleston took its first steps toward becoming an epicenter of the Lost Cause.49

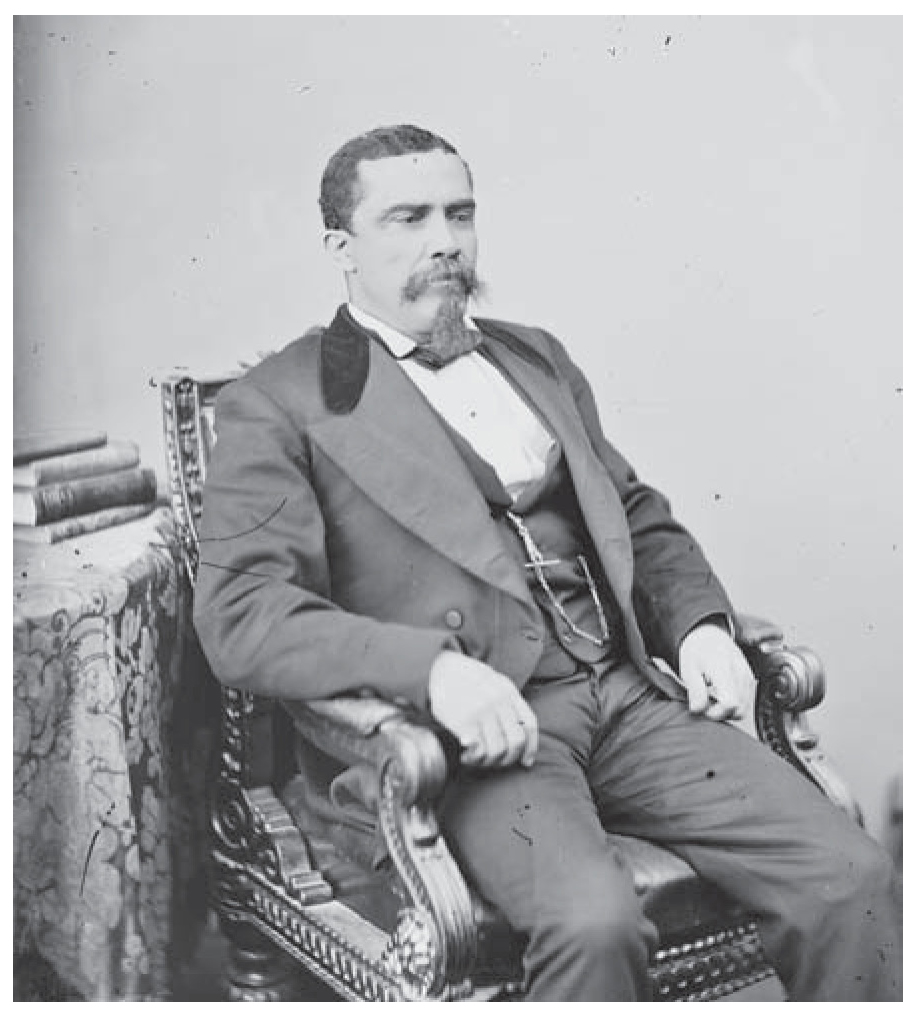

Coined by Richmond Examiner editor Edward A. Pollard, who published The Lost Cause; A New Southern History of the War of the Confederates in 1866, the term “the Lost Cause” quickly became shorthand for a southern defense of the Confederacy. Like many myths, the Lost Cause comprised a host of arguments and rationalizations, but two of them, which are neatly encapsulated in the phrase itself, loom the largest. First, the Confederate Army had no real chance to win the Civil War. Facing off against a superior force—with greater resources and manpower—Confederate soldiers had waged a valiant, yet ultimately doomed, fight. That the boys in gray had lasted as long as they did was a testament to their bravery, fortitude, and military prowess. Second, the cause for which Confederates fought was, in fact, a cause worth fighting, even dying, for. This second central component implicitly raised a crucial question: had the Confederacy launched a devastating, four-year war to defend slavery?50

Before the war, as we have seen, this was no question at all. Southerners announced loudly and proudly that they went to war to preserve an institution they viewed as the foundation of their economy, society, and culture. After the war, however, the answers ex-Confederates gave to the question were not nearly so honest or straightforward. Some white southerners readily admitted that the war had been waged to protect slavery, but many others—worried about losing the moral high ground to proponents of an emancipationist vision of the war—scrambled to distance the Confederacy from the peculiar institution. At times, this meant simply highlighting more easily defensible causes. “We contended for a great principle,” Reverend John Bachman told a small group of ladies at the first meeting of the LMAC on May 14, 1866. “The right of self-government; a principle for which our fathers fought and bled.”51

Other Lost Cause partisans insisted that while slavery played a role in the Civil War, it paled in comparison to more noble goals and principles. At an 1871 Magnolia Cemetery ceremony honoring the return of the remains of South Carolinians who had fallen at Gettysburg, Reverend John L. Girardeau insisted that the preservation of slavery was less important to Confederates than was the maintenance of the “fundamental principles of government, of social order, of civil or religious liberty.” With an eye as much on the Radical Republican threats of the present as on the Confederate past, he urged South Carolinians to keep up the fight that the deceased had started. “Heroes of Gettysburg! Champions of constitutional rights! Martyrs for regulated liberty! Once again, farewell! . . . Rest ye, here, Soldiers of a defeated—God grant it may not be a wholly lost—Cause!”52

Girardeau’s memorial address underscores another reason why Lost Cause prophets in the late 1860s and 1870s de-emphasized slavery. Immersed in a struggle against Republican rule, they gravitated toward arguments that spoke directly to Reconstruction politics. With slavery relegated to the dustbin of history, hitching the Lost Cause to contemporary concerns—like states’ rights, low taxes, and the protection of constitutional liberties—seemed an effective way to turn it into a useable past.53

Putting the Lost Cause to work, however, necessitated a good measure of willful forgetting. Confederate memorialists proved equal to the task. “The world has been wickedly taught and foolishly believes that we resorted to war solely to preserve our institution of African slavery,” General John S. Preston told a SASC meeting in Columbia in 1870. If anyone knew what had led to the Civil War, it was Preston, who not only attended the South Carolina Secession Convention but also served as the state’s official delegate to Virginia’s secession convention. The North and South were antagonistic societies whose differences were fundamentally rooted in slavery and race, he had told the Virginia convention in February 1861. But a decade later, Preston preached that slavery had not been the animating cause of secession at all.54

In the same vein, South Carolina’s leading fire-eater Robert Barnwell Rhett Sr. had made a career out of urging southern states to secede from the Union in defense of the peculiar institution. Yet when he sat down to write his Civil War memoir in the late 1860s and early 1870s, Rhett minimized the role of slavery in precipitating the secession crisis. He even censored himself. After pasting into his memoir portions of an 1860 speech, Rhett crossed out a line in which he maintained that the North’s sectional tyranny was “organized on a hatred of the institution of slavery.”55

The defensive posture struck by Preston and Rhett highlights an important point—one that can be obscured by our tendency to reason backward from later developments. By the early twentieth century, Lost Cause tenets had become widely accepted, and not just in the South. During Reconstruction, however, they functioned as a countermemory rather than as the master narrative, especially in cities like Charleston. Lost Cause proponents there began on the defensive, and, in classic fashion, they started from the local and personal, fashioning a narrative of the Civil War that directly opposed the emancipationist vision of the conflict, which predominated. As Thavolia Glymph has argued, “The Lost Cause movement stands as an explicit rejoinder to the memory-work of black southerners”—and, it should be added, their white Republican allies—“not the other way around.”56

* * * *

WHILE WHITE SOUTH Carolinians worked to disassociate slavery from the Confederate cause, Republicans in the state invoked memories of the peculiar institution every chance they could get. Thriving on the moral capital provided by emancipation, party leaders reminded South Carolina voters—most of whom were former slaves—that it was Democrats who had supported and fought to maintain slavery, while Republicans had presided over its demise. Just as northern representatives, such as Pennsylvania congressman Thaddeus Stevens, invoked the terrible costs of the Civil War to motivate predominantly white electorates—the “bloody shirt” appeal—South Carolina Republicans deployed memories of human bondage to motivate the state’s many black voters. In the Palmetto State, in other words, shaking the shackles of slavery was a more potent rhetorical tool than waving the bloody shirt.57

Charleston’s Republican newspapers, such as the short-lived Free Press, cast their Democratic opponents as “the old states-rights pro-slavery element” and peppered columns on contemporary political issues with references to “the crimes of slavery.” Meanwhile, Republican operatives distributed campaign literature that accused the postbellum Democratic Party of having a proslavery agenda. In the months preceding the presidential election of 1868, the Charleston Daily News reproduced a campaign document that the paper claimed had been widely circulated across the South. Intended to drum up support for Republican candidate Ulysses S. Grant, the document consisted of a series of questions and answers that painted the Democratic Party as being dominated by Confederates and slaveholders who hoped to return freedpeople to bondage.58

Republicans also stoked memories of slavery at public rallies and in interviews with northern newspapers. When State Executive Committee chair Alonzo Ransier spoke at an 1869 protest, he offered a passionate denunciation of life under slavery. The following year, while campaigning in Spartanburg as the Republican nominee for lieutenant governor, Ransier framed the election as rooted in a lingering divide over the question of human bondage. The 1870 race pitted incumbent governor Robert K. Scott and Ransier against Richard B. Carpenter and his running mate M.C. Butler, who had been nominated by the fusionist Reform Party. Although this new party had pledged its support for black political equality, Ransier viewed it as little more than a proslavery wolf in sheep’s clothing. The Republicans, he insisted, were the genuine antislavery article.59

By portraying slavery as a partisan issue, Ransier sought both to defame his political rivals and to attract support from some white voters. Slavery not only put black men in chains, he argued, it also prevented poor white men from being able to support their families. Ransier was not the only South Carolina Republican who thought that poor whites could be swayed by shaking the shackles of slavery. The Free Press targeted rank-and-file veterans of the Confederate Army during these years. Former rebel soldiers, insisted the Charleston weekly before the April 1868 state election, had “never heard of Republicanism except through a press which caricatures its exponents, misrepresents its ideas, [and] vilifies its practices.” The Free Press editors, however, believed that a full explication of party doctrine, as well as a reminder of the lowly place nonslaveholding whites had played in the state’s antebellum pecking order, would yield Republican converts.60

It was not just officeholders like Ransier and Republican newspapers like the Free Press that infused recollections of slavery into political debates. Former slaves did, too. During the Charleston mayoral election of 1871, Charleston Democrats tried to build bridges to black voters by highlighting the party’s diverse slate, which included Irish, German, and African American candidates. Unconvinced by this argument, black residents displayed a campaign banner that pointedly asked, “We have played together you say, but were we ever whipped together?”61

Alonzo J. Ransier was a freeborn black Charlestonian who became lieutenant governor of South Carolina and a U.S. congressman during Reconstruction.

In the meantime, conservative politicians scrambled to avoid being tainted by the brush of slavery. Decrying the nefarious “parrot cry” about the institution, they complained that each new election cycle brought about the same accusations. Just weeks before voters decided the 1870 gubernatorial race, the Charleston Daily News denounced the claim spread by Republican incumbent Robert K. Scott and his allies that white conservatives sought to restore slavery. Black South Carolinians were free and would remain so, insisted the paper’s editor, Frank Dawson. “Neither this State, nor the whole South,” would “restore African Slavery,” even if it could.62

In 1874, Dawson’s newly founded Charleston News and Courier published numerous accounts of Republicans telling blacks that they would be re-enslaved if their conservative opponents prevailed. This notion was ludicrous, maintained Dawson, but it was an effective trick nonetheless. After Republicans retained control of the governorship and the General Assembly in elections a few weeks later, the Charleston editor blamed the state’s Republican newspapers: “The Scalawag and Carpet-Bag organs in this State continue to fume and fret and to invoke the memories of Slavery and Sumter, to enable them to retain their hold upon the negro.”63

South Carolina conservatives not only dismissed Republican charges that they had supported or hoped to reintroduce slavery; at times they used their own memories of slavery—however fanciful—to recriminate the Republican Party and its actions. The Charleston Mercury pronounced in October 1868, “Whilst Radical emissaries are traversing the South, and striving to excite the black against the white population, on account of the past institution of slavery, it may not be useless to show the part the Northern people took in putting it upon this continent.” To this end, Rhett’s paper published a table suggesting that New England slave traders had imported far more slaves into Charleston between 1804 and 1808 (when the trade was outlawed by federal law) than had South Carolinians. When Charleston native and Washington College president W.J. Rivers addressed the South Carolina Historical Society eight years later, he focused on the flawed process of Republican-led emancipation. Southerners should not be blamed for the institution, maintained Rivers, who added that they might have voluntarily ended slavery given sufficient time.64

A few South Carolina Democrats went further than Rivers, framing their party, or white conservatives more generally, as the real abolitionist force in the state. Charleston Courier editor Thomas Y. Simons made a special appeal to black voters to support the Democratic Party on the basis of its emancipatory actions. “By the act of the white people of her own soil, slavery was forever abolished within her limits,” he insisted in an August 1868 editorial. Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation was of questionable legality, but “the white race here, in Convention assembled, removed of their own accord, all doubts, by declaring as a part of the fundamental law, the extinction forever of slavery.” Ignoring the Johnson administration’s stipulation that South Carolina could not return to the Union unless it ratified the Thirteenth Amendment, Simons concluded that the state’s freedpeople “owe their unquestioned freedom and equality before the law” to “their old masters.”65

This misinformation campaign reached its zenith during the election of 1876. That year, South Carolina Democrats had high hopes that homegrown hero and gubernatorial candidate Wade Hampton would enable them to break the Republican stranglehold in the state. Democrats in most other former Confederate states had already achieved this feat, combining fraud, harassment, and violence to reassert their political dominance. In 1876, South Carolina was one of only three states that had yet to be “redeemed,” a term white southerners employed so as to invest the reassertion of white supremacy with biblical authority. Since blacks in South Carolina enjoyed an electoral advantage of between twenty thousand and thirty thousand votes, Redemption there seemed to necessitate something more than the usual tactics—actually attracting some African American support. Thus, South Carolina Democrats formulated a two-pronged approach. Following Confederate general Martin W. Gary’s “Edgefield Plan,” thousands of rifle and sabre club members from across the state sought to limit Republican turnout by donning red shirts, arming themselves to the teeth, and terrorizing Republicans. At the same time, Hampton and other leading Democrats sought to win over at least a few black voters with calls for peace, moderation, and equal rights for all.66

One of the central planks of the latter strategy involved challenging the Republican Party’s antislavery record. On September 27, 1876, the News and Courier published an open letter by Democratic ex-governor Benjamin Perry to Hampton’s opponent, Republican incumbent Daniel Chamberlain. In this lengthy, front-page epistle, which was entitled “Who Freed the Slaves?” Perry noted that “the colored people have been told over and again by their unprincipled leaders that if they voted for the Democratic party, they would be thrown back into slavery again.” Perry took issue with Chamberlain’s claim that the Republicans had liberated the enslaved and thus deserved the support of black voters. Instead, like Thomas Y. Simons, Perry credited the planter class for emancipation. “The State Convention of South Carolina, representing all the slaveholders of the State, did almost unanimously, in 1865, abolish slavery, and declare in their constitution that it should never exist again in the State,” he insisted. “In this way, and in no other, was slavery abolished in South Carolina.”

Next, Perry set his sights on the Republicans’ antebellum record on slavery. Conflating the Republican Party in particular with the North in general, Perry offered an indictment of Republican racial attitudes and actions that ran roughshod over the historical record. Despite the fact that the party was not founded until the mid-1850s, he claimed that its members had not only introduced and profited from the African slave trade, but also had “owned slaves themselves and kept them till the population of the Northern States became so dense that slave labor was no longer profitable.” Perry balanced such exaggeration and misinformation with well-founded critiques of Republican timidity when it came to embracing an antislavery agenda in the early stages of the war. He failed to contextualize his criticism of Republican failings, however, and entirely ignored the Confederacy’s proslavery agenda.67

Hampton supporters echoed Perry’s points on the campaign trail. So, too, did a handful of former slaves. At a Democratic club meeting in Summerville, for instance, freedman John Gregory publicly declared himself a victim of Republican lies. For eight years, party leaders had “made him believe that to vote with the white men of the State was to assist them in returning slavery upon his race.” But now Gregory “realized that this was only the argument of men who wished to retain themselves in office and power.”68

The disputed nature of the 1876 election—which was marred by ballot stuffing, intimidation, and outright violence, including two bloody riots in Charleston—makes it impossible to determine the effectiveness of this propaganda campaign. Both Republicans and Democrats claimed victory in the races for governor and control of the General Assembly. The outcome of the presidential election, which pitted Republican Rutherford B. Hayes against Democrat Samuel J. Tilden, was also in question when voting closed on November 8, as several southern states, including South Carolina, recorded contested results. In the pivotal race for governor, estimates of blacks who voted for Hampton ranged from 3,000 (according to Chamberlain’s camp) to 17,000 (according to Hampton’s). Whatever the case, the conservative drumbeat about slavery that fall makes it clear that Democrats believed that certain memories of human bondage—carefully shaped and deployed by party operatives—might bring black voters into their column.69

* * * *

WHITE CONSERVATIVES DEVOTED far less time to denouncing shackle shaking after the Bargain of 1877. This backroom deal ended the disputed 1876 presidential election in favor of Republican candidate Hayes and, in the process, brought Reconstruction to a close in South Carolina (and Louisiana). Once President Hayes removed federal troops from the statehouse in April, Chamberlain and his Republican allies were forced to surrender their offices. Hampton and his Red Shirts had redeemed South Carolina. By the end of the year, Democrats would take over not just the state government but also most local municipalities, including Charleston. Through control of election machinery, coercion, and eventually legal disenfranchisement, white conservatives instituted a political mono poly that would last into the 1960s.70

Invocations of slavery no longer seemed so politically potent in this new context. An 1880 News and Courier column on a Republican rally in Darlington County, for instance, buried the topic in its lengthy list of outlandish and thus benign grievances: “The speeches were about as usual, the main idea being that the Democrats are allied to the Devil; don’t furnish public schools; will restore negroes to slavery; will repeal the Thirteenth, Fourteenth and Fifteenth amendments.”71

White complaints about black festivals of freedom also began to fade as Republican political power dwindled. In 1877, the News and Courier praised the Emancipation Day celebration, which had been postponed to January 8 because of the chaos that followed the disputed election, as the best the city had seen. “A noticeable feature of the celebration,” held the paper, “was the almost entire absence of anything like politics, which might possibly be accounted for by the absence of the white carpet-bag element which was once a prominent feature in these celebrations.” Fifteen years later, in 1892, the News and Courier again complimented the Emancipation Day parade staged by black militia companies for being “entirely devoid of any of those unpleasant features which have marred the occasion in the recent past.”72

Fourth of July commemorations after 1876 were similarly devoid of politics. African Americans continued to celebrate the day by flooding city streets and parks, buying food and drink in White Point Garden, and dancing the Too-la-loo, which became shorthand for black celebration of the holiday. And, remarkably, African American militia companies—which were not disbanded but rather were relegated to ceremonial duties after the return of Democratic rule—also kept parading through downtown Charleston on the Fourth through the late 1890s. Judging by local newspaper coverage, however, the holiday was strictly commemorative and festive after Redemption. In a nod to the leader of the new political order that produced this change, the News and Courier’s 1877 column on the celebration was titled “A Hampton Fourth of July.”73

Slavery remained a topic at such celebrations, but decoupled from Republican politics it no longer seemed so threatening to white Charlestonians. The battle over how to remember slavery, the Civil War, and emancipation would rage on for decades—and, as we shall see in chapter 4, Charleston Lost Causers, including News and Courier editor Dawson, played a prominent role in this fight. But things were different after Reconstruction, and nothing symbolized this new context better than a large statue erected a decade after Redemption. In April 1887, on the south side of the Citadel Green, white Charlestonians unveiled a monument to John C. Calhoun—slavery’s greatest champion.74