AS WHITE CHARLESTONIANS IMPOSED JIM CROW LAWS and customs on their hometown, they transformed it from the Cradle of the Confederacy into a cradle of the Lost Cause. Enthusiasm for all things Confederate seemed boundless during these years. The city’s earliest Civil War memory organizations, including the Ladies’ Calhoun Monument Association, the Ladies’ Memorial Association of Charleston (LMAC), and the Survivors’ Association of Charleston (SAC), continued to meet regularly, stage Memorial Day services, sponsor lectures on the conflict, and install Confederate monuments and memorials. They were often joined in these activities by local militia groups, including the Sumter Guards, the Washington Light Infantry, the Charleston Light Dragoons, and, after the Citadel reopened in the early 1880s, its cadets.1

Toward the end of the nineteenth century, white Charlestonians embraced the new wave of Confederate remembrance that swept across the South. In the summer of 1893, some 150 veteran members of the SAC resolved to transform the group into Camp Sumter of the United Confederate Veterans (UCV), a national organization created in 1889. The following November the junior members of the SAC—who as sons of veterans were prohibited from joining the UCV—formed Camp Moultrie of the newly organized Sons of Confederate Veterans (SCV). That same month, at the urging of the Charleston News and Courier, several Charleston women formed the fourth chapter of the recently established United Daughters of the Confederacy (UDC), which became South Carolina’s leading chapter. Over the next decade, Charleston UDC members opened the Confederate Museum in Market Hall on Meeting Street to display war relics and began publishing a monthly ladies magazine, the Keystone, which served as the official organ of the Daughters in southeastern states. Meanwhile, local men founded two additional SCV camps and three more UCV camps.2

A souvenir program from the 1899 United Confederate Veterans national reunion, held in Charleston.

In 1899, Charleston played host to the United Confederate Veterans national convention. Seven thousand veterans crowded into Thomson Auditorium, hastily erected specifically for the event, to attend the day’s opening meeting. “It is peculiarly fitting, sirs,” pronounced one of the speakers, “that this, your last great Reunion of the nineteenth century, should be held in historic old Charleston, which is well called the Cradle of the Confederacy. Here—where the tocsin of war was first sounded—where so much of the history of that great struggle was enacted, and where the very atmosphere is instinct with hallowed memories of that war.” Observing the feverish preparations for the reunion, North Carolina publisher Walter Hines Page wrote that Charlestonians “talk about that meeting as devout Jews might talk about assembling of all the tribes of Jerusalem.”3

Reminders of the city’s Confederate sympathies were everywhere. Statues and memorials to ideological inspirations such as Calhoun, military leaders such as P.G.T. Beauregard, and the Confederate fallen dotted the landscape, from White Point Garden at the Battery to Magnolia Cemetery on the northern outskirts of town. After 1901, Charleston even had a tribute to Henry Timrod, the Confederacy’s unofficial poet laureate. Not far from the Timrod Memorial in Washington Square lay a more animate memorial to the Confederate cause: the Home for the Mothers, Widows, and Daughters of Confederate Soldiers. Founded in 1867 by LMAC president Mary A. Snowden, her sister, and a handful of other women, the Confederate Home was located on a sizable Broad Street property. Over the next six decades, it provided food and shelter to Confederate mothers, widows, and daughters as well as a private education to young women.4

Outsiders were struck by the prevalence of the Confederate flag and near absence of America’s banner in Jim Crow Charleston. One northern tourist claimed to have seen some fifty Confederate flags when he visited in 1885. Ohio transplant John Bennett observed that American flags were not displayed in front of city homes until after World War I. Many white Charlestonians, meanwhile, rejected the reconciliationist spirit that took hold of the country, north and south, during this period. Asked in 1889 whether they would be willing to celebrate Confederate Memorial Day on the same day that the northerners observed their own Memorial Day, several directresses of the LMAC rejected the notion. The bitterness and cruelty of the war had been largely forgiven, explained one member, “but we cannot mix up principles and sentiments as such a change in the day would imply.”5

Unwilling to give up any ground in the struggle over how the Civil War would be remembered, groups like the LMAC made Charleston among the South’s most important sites of Confederate veneration. In this crusade, they were helped immeasurably by a small coterie of Charleston journalists, editors, and historians, individuals who helped reshape the Lost Cause from countermemory into master narrative, not just across the South but across much of the country.6

* * * *

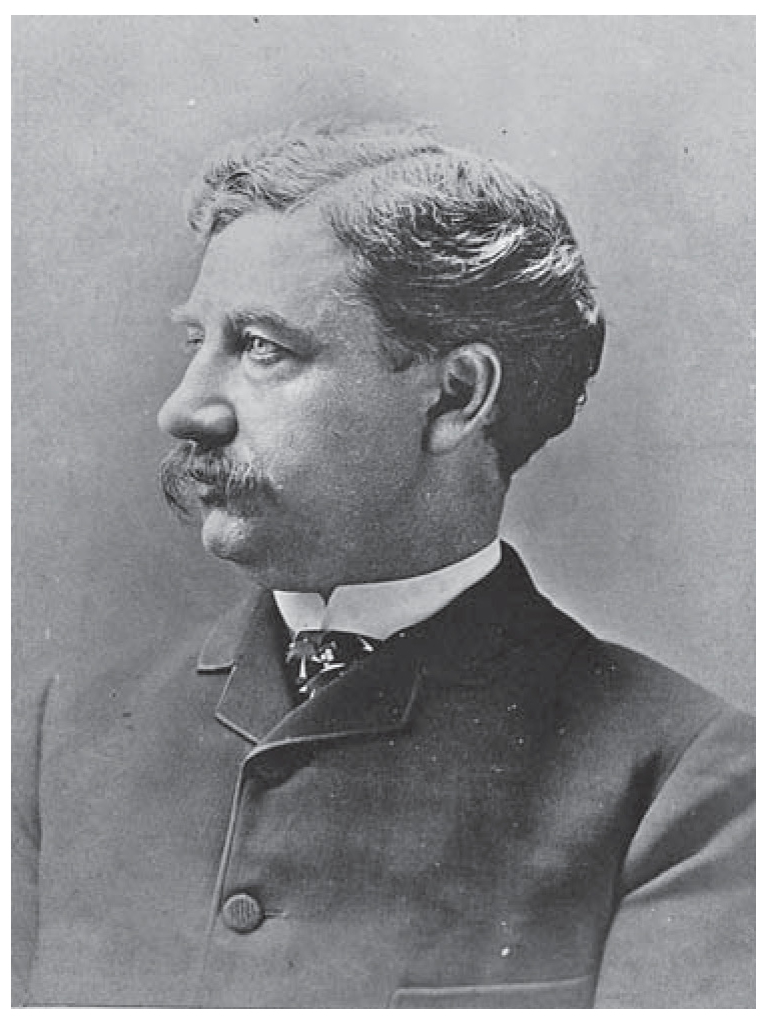

THE CHIEF VEHICLE for spreading Lost Cause gospel in Jim Crow Charleston was the Charleston News and Courier, which between 1873 and 1910 was edited by Frank Dawson and James C. Hemphill. Swept up by the Confederate cause, English-born Dawson had left his native country in 1862 to fight with the secessionists, seeing action at Fredericksburg, Gettysburg, and Spotsylvania. Following a brief stint at two Richmond newspapers after the war, he moved to Charleston in late 1866 to become an assistant editor for the Charleston Mercury. Dawson only lasted about a year at the struggling newspaper before buying a share first of the Charleston News and later the Charleston Courier, which the Englishman and his partners combined into the Charleston News and Courier in 1873.7

English-born Frank Dawson, ca. 1888, was a Confederate veteran and editor of the Charleston News and Courier.

Dawson turned the News and Courier into one of the South’s leading papers. As of 1880, only two New Orleans newspapers enjoyed greater daily readership in the states of the former Confederacy. Under Dawson’s stewardship, the News and Courier doubled in size and expanded its reach throughout the state by delivering the paper by railroad. “Never in South Carolina’s turbulent history has a single paper so dominated the thought of the state,” according to historian Robert H. Woody.8

The News and Courier continued to enjoy the widest daily circulation in South Carolina after James C. Hemphill took charge in 1889. Like so many other Old South apologists of his generation, this Upcountry South Carolinian compensated for being born too late to participate in the Civil War by becoming active in Confederate memory organizations and activities. In 1890, Hemphill was one of the honored guests at the unveiling of the monument to Robert E. Lee in Richmond, Virginia. Eight years later, Hemphill served on the executive committee for the 1899 national UCV reunion.9

Broad Street offices of the influential Charleston News and Courier, champion of the Lost Cause, ca. 1870s–1880s.

Under both Dawson and Hemphill, the News and Courier crafted an idealized picture of the Old South and the noble soldiers who had fought to defend it. To be sure, the editors were not entirely stuck in the past. In the face of an apathetic business class in Charleston, Dawson and Hemphill used the News and Courier to trumpet the same sort of economic revitalization that was at the center of Atlantan Henry W. Grady’s New South ethos. Yet they also worried that calls for a New South could easily be misconstrued as a critique of the Old South and the Confederacy. “It is not for the sons to apologize for their fathers,” wrote Dawson in 1886. “They need no apology . . . . The South fought for the right—for the undying principle of self-government . . . which was as ‘eternally right’ in 1860 as in 1776.” Hemphill was even more outspoken when it came to denouncing Grady’s vision for a New South, publishing a column that critiqued the phrase for conveying “the suggestion of an old South, sullen, rancorous, impracticable and reactionary.”10

With Dawson and Hemphill at the helm, the News and Courier did more to downplay slavery as a cause of the Civil War than perhaps any other newspaper in the region. Indeed, judging by a June 1885 article in the Upcountry Laurensville Herald, the News and Courier had a reputation for its tireless defenses of the Confederacy on precisely this score. Just one month earlier, Frank Dawson had reprinted an account of a postwar interview with Robert E. Lee in which the general said that he had been disturbed by northern claims that “the object of the war had been to secure the perpetuation of slavery.” This was “not true,” insisted Lee, who “rejoiced that slavery is abolished.” Dawson, for his part, added that Lee’s sentiments reflected the general consensus across the South, positing that “Grant’s army would have made short work of their opponents if they had encountered only those Confederates who were fighting for the perpetuation of slavery.” The Laurensville Herald took issue with these claims. The North understood that emancipation would follow with Union victory, the paper argued, and the Confederate Army consisted chiefly of slaveholders and their sons.11

Unwilling to let this challenge go unmet, Dawson reprinted the Herald column and published a lengthy rejoinder that responded to its claims point by point. The Charleston editor excerpted Lincoln, painting a picture of a president who went to war solely to preserve the Union and who, when he finally embraced emancipation, did so not for principled reasons but rather as a military necessity. Turning to the question of the motivations for secession, Dawson declared, “Our position is that slavery was merely the immediate cause, or provocation, of the war, and not the fundamental cause.” The conflict was rooted in basic philosophical differences that dated back to the birth of the nation—differences over the scope and power of the federal government. Finally, Dawson sought to debunk the Laurensville Herald’s claim that the Confederate war had been fought by slaveholders and their sons by reproducing estimates of the extent of slave ownership among southerners made by secessionist editor James D.B. DeBow. According to the News and Courier’s calculations—which relied on numbers that DeBow himself had publicly disavowed in 1860—only one out of every thirty-six Confederate citizens owned a slave and, as of 1864, ten out of every eleven Confederate soldiers were non slaveholders.12

Dawson’s position on the relationship between slavery and the Civil War contrasted sharply with that espoused by fellow New South newspaperman Henry W. Grady. The influential editor of the Atlanta Constitution, Grady was a tireless promoter of economic revitalization in the South and sectional reconciliation with the North. Although he believed that slavery was not without its benefits, especially for African Americans, Grady called for an end to sectional hostilities based on a mutual acceptance of the war’s righteous outcome. “There have been elaborate efforts made by so-called statesmen to cover up the real cause of the war,” declared Grady in 1882, “but there is not a man of common sense in the south to-day who is not aware of the fact that there would have been no war if there had been no slavery.”13

Dawson would have none of this. Reproducing a critique of Grady originally published by the Mobile Register, the Charleston editor chastised the Atlanta Constitution “for dragging forward the skeleton of Slavery as the cause of the war.” Uncowed, Grady fired back with a series of editorials aimed at both the Register and the News and Courier—newspapers, he marveled, that questioned the idea that slavery was essential to the coming of the war. “Our esteemed contemporaries assert—or, rather, they intimate, that the war was fought in defense of local self-government,” wrote Grady. How is it possible, he wondered, for the South to have lost the war for self-government but nonetheless retained full control of local affairs?14

In his response, Dawson admitted that slavery contributed to the conflict and even allowed that had there “been no slavery there would have been no war.” But, the Englishman added, it could just as accurately be asserted “that if there had been no United States there would have been no secession.” Invoking his own service in the Confederate Army, Dawson also denied that his fellow soldiers had fought for slavery. Grady’s insistence that “they were willing to dissolve the Union, and sacrifice their own blood and the blood of their children, for no other or higher reason than to save their negroes and enhance the value of the slaves by establishing a ‘Slaveholding Confederacy’” was an insult to “the whole Southern people,” concluded Dawson.15

As Dawson’s exchanges with both Grady and the editor of the Laurensville Herald illustrate, the Charleston newspaperman did not suppress dissenting voices when it came to slavery and the Civil War. The same was true of his successor, James Hemphill, who also went out of his way to provide room in the News and Courier for other perspectives, if only to hammer home the validity of his own. Five years after he took charge of the paper, Hemphill reproduced portions of a Rhode Island newspaper column that claimed that the Civil War was waged to perpetuate slavery. If this were the case, asked Hemphill, what did the North go to war to accomplish? Highlighting comments by Lincoln and William Tecumseh Sherman that suggested that the war had been fought neither to end slavery nor to help African Americans, the editor held that it was difficult to understand why the Confederacy went to war “to defend an institution that was not assailed.”16

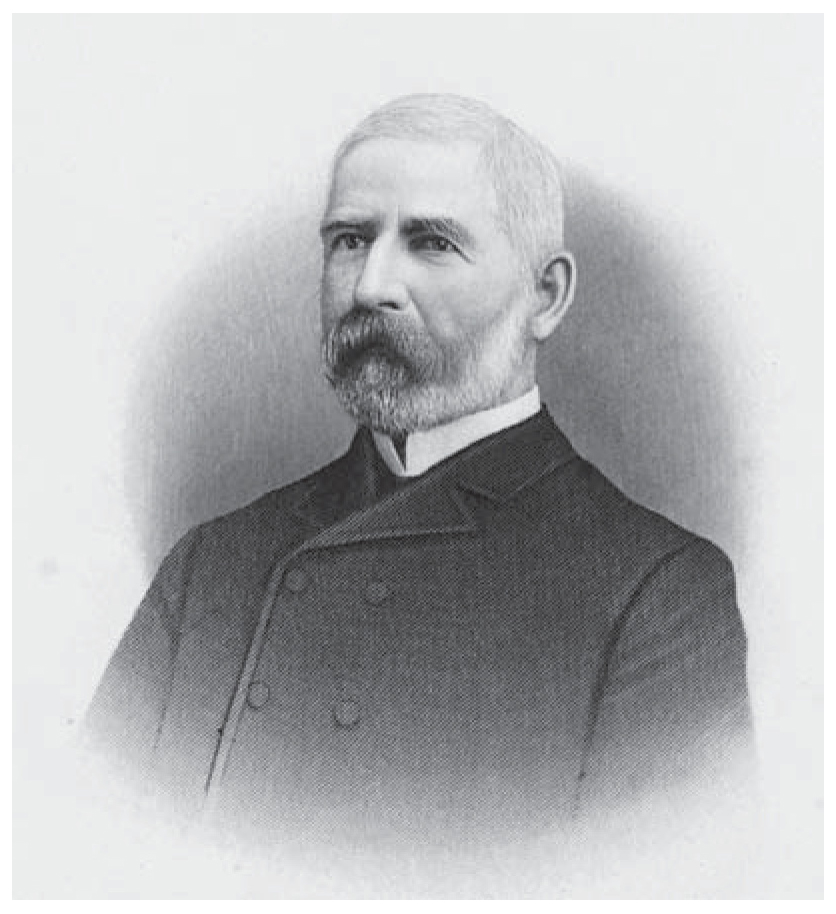

The News and Courier was not alone in this fight over the memory of the war. Charleston veterans who had achieved positions of leadership in local historical, educational, and publishing circles lent crucial support. Perhaps the most prominent was Edward McCrady. A Confederate officer who had suffered multiple injuries during the war, McCrady was a long-serving state representative with a thriving law practice. But his heart was in the past. A founding member of the SAC, McCrady wrote several histories of early South Carolina and served as president of the South Carolina Historical Society and vice president of the even more influential American Historical Association. McCrady also regularly addressed reunions of Confederate veterans, and a number of these speeches were reprinted in the Southern Historical Society Papers, one of the nation’s leading Lost Cause founts.17

“We did not fight for slavery,” McCrady pronounced before a group of veterans in Williston, South Carolina, on July 14, 1882. “Slavery, a burden imposed upon us by former generations of the world, a burden increased upon us by the falsely-pretended philanthropic legislation of northern States . . . , was not the cause of the war.” Instead, McCrady held that slavery was merely “the incidents upon which the differences between the North and the South, and from which differences the war was inevitable from the foundation of our government, did but turn.” The real crux of the matter, he concluded, was the right of South Carolinians to control the affairs of their state, especially its race relations, without outside interference.18

McCrady’s explanation—describing slavery not as the cause of the conflict but rather as incidental—was, as historian David Blight has observed, “almost omnipresent in Lost Cause rhetoric.” A few years after McCrady framed slavery as incidental, his longtime SAC colleague Cornelius Irvine Walker echoed this defense at a Memorial Day gathering held at Magnolia Cemetery. A native Charlestonian from a family with an established paper and publishing firm, Walker, like McCrady, played a leading role in Confederate resistance and remembrance. He was a founding member of the SAC, worked to redeem South Carolina by forming the Carolina Rifle Club, helped reopen the Citadel, and served as commander of the state division of the UCV and commander in chief of the national UCV. As head of the firm Walker, Evans, & Cogswell, which produced numerous early guidebooks, Walker was also a loud voice in Charleston’s publishing and tourism industries. He even authored his own visitor’s guide.19

Charleston attorney and historian Edward McCrady Jr. was a Confederate veteran and Lost Cause prophet.

When Walker addressed those who had gathered at Magnolia for the twentieth century’s first Confederate Memorial Day, on May 10, 1900, he spent much of his time defending the immortal principle of states’ rights, which, as he put it, “we all imbibed at our mother’s breast.” Evoking and contradicting Alexander Stephens’s cornerstone metaphor—which held that the Confederacy was founded on the “great truth” of slavery—the Charleston veteran pronounced: “On this rock of States’ rights was the secession of the Southern States founded and on it was builded [sic] the Southern Confederacy. We were but upholding the principles of our forefathers and those of the original thirteen States.” The UCV leader declared that Confederate soldiers did not go to war to prevent the liberation of its slaves but rather to stop Union soldiers from desecrating their homes. In the end, Walker concluded, “slavery . . . was a mere incident of the struggle, not its cause.”20

* * * *

ONE CURIOUS FEATURE of Lost Cause rhetoric is its conflicted position on slavery. Spokesmen like McCrady and Walker dismissed slavery as incidental to the Confederate struggle, and yet they devoted a great deal of ink to highlighting the centrality of slavery in the Old South. This almost bifurcated conversation forced Confederate enthusiasts to walk a fine line between defending an institution that many people viewed as outdated, if not unjust and inhumane, and renouncing the beliefs and practices of their forebears—which were, after all, central to their own identity. To solve this dilemma, Lost Causers deployed two distinct arguments. Some attempted to absolve the South of responsibility for slavery. Others mounted a full-throated defense of the institution as a civilizing influence. A few made both points simultaneously, despite the seeming incompatibility of these positions—why, after all, would one bother to deny the South’s culpability for slavery if one believed it had been a good thing? In every case, however, the project was the same, even if the contradictions remained: reinforcing the moral sanctity of the Lost Cause.

Many Confederate memorialists insisted that slavery was a burden that had been imposed on the South by outsiders. “We of this generation had no part in the establishment of slavery in this country,” Edward McCrady told the veterans who gathered in Williston in 1882. Nor did he blame his southern ancestors. McCrady instead pointed his finger at England, from which the South had inherited slavery, and the North, which had transported thousands of slaves from Africa to ports like Charleston and then later cast its enslaved people off on the South through the bogus philanthropy of emancipation. Replete with countless facts and figures to support it, McCrady’s disquisition no doubt convinced its sympathetic audience that Rhode Island was chiefly responsible for South Carolina’s slave trade.21

Dawson and Hemphill likewise took great pains to exonerate the South of any responsibility for the institution of slavery. New Englanders and Englishmen monopolized the slave trade, Dawson insisted on April 19, 1885, while the South’s antislavery sentiment “grew stronger and stronger, until it was arrested, and turned back upon itself, so to speak, by the fanatical action of Northern agitators.” A few weeks later, Dawson printed a letter to the editor that went one step further. Opposition to slavery, insisted the News and Courier’s Camden correspondent, had been so strong in South Carolina in the early nineteenth century that in 1816 a number of planters and other gentlemen from the Upcountry formulated a plan to end both the slave trade and slavery itself. “No more forcible language,” he maintained, “was ever used by the Anti-slavery party than was found in that document; sentiments that would have rejoiced the philanthropic heart of Phillips, Garrison, Tappan or Sumner, and others of that ilk.”22

Robert E. Lee’s grandson Robert E. Lee III took this specious line of argument to extraordinary lengths when he visited Charleston in January 1909. He was in town to celebrate his grandfather’s birthday, which by then was a state holiday in South Carolina and three other southern states. Southerners never trafficked in slaves, Lee told the large audience sitting in German Artillery Hall (formerly Military Hall), which was located just a few blocks north of Charleston’s slave-trading district. Running roughshod over the historical record, he also maintained that the South had tried to solve the problem of slavery only to be defeated by Great Britain and later the New England states. “The Federal Constitution called for emancipation of all slaves in 1800, but the influence of the New England delegates had this date changed to 1820, which later resulted in the Missouri Compromise,” he argued. Notwithstanding these nonsensical claims, the local media printed fawning accounts of Lee’s speech. The monthly ladies journal the Keystone, which was published in Charleston by United Daughters of the Confederacy members Mary B. and Louisa B. Poppenheim, called the address “a wonderful presentation of the subject, epigrammatic and condensed, presenting historic truths in so simple, clear and direct a form that the average intelligence was able to grasp many salient historic points.”23

When Lost Cause stalwarts were not denying responsibility for slavery, they were vigorously defending its merits. In 1873, for example, Dawson published a column responding to a New York Evening Post article that suggested that it was slaves’ uncompensated labor that had made possible the luxurious lifestyle of the master class. This gross misrepresentation of southern slavery demanded correction, insisted the News and Courier editor. “In exchange for the labor of the working hands, in a family of slaves, the planter gave clothing, shelter and medical attendance to the whole family, young and old; the children, too young to work, were fed and clad, and the like was done for those who were too old to work,” he wrote. “This was what the planter paid his slaves, and it is more than most ordinary field hands can make now.”24

Charleston’s Lost Causers also sought to downplay the fear of slave insurrection. In an 1879 speech before the Washington Light Infantry that received front-page coverage in the News and Courier, former Citadel professor Hugh S. Thompson offered a sanitized outline of the military academy’s origins. The Citadel, he explained, was built as a cost-cutting measure that allowed state officials to save money by substituting cadets for the paid guards who watched over the war munitions stored in Charleston. Glossing over the main reason that Charleston kept a formidable stockpile of weapons—to put down slave rebellions—the future governor of the state spun a reassuring tale to the members of the infantry, many of whom, like Thompson himself, were Citadel graduates.25

To be fair, local whites did not entirely dismiss the threat of slave revolts. In 1885, Dawson provided a lengthy account of the 1822 Denmark Vesey conspiracy in a Sunday edition of the News and Courier. The article highlighted the ruthlessness of Vesey and his colleagues, insisting that they had planned to pan out through city streets, murdering any white person they found. The larger point drawn from this episode, however, was not that the slave regime was so brutal that even a free black like Vesey was willing to contemplate armed insurrection. Rather, it was that the failed uprising proved the rule of slaveholder benevolence. Conveniently overlooking insurrections such as the Stono Rebellion, which erupted in 1739 just to the south of the city, the paper concluded that Vesey’s conspiracy was “the only attempted insurrection of any importance which took place in South Carolina.” This article reflected Dawson’s belief that slavery, though ultimately a doomed institution, was for black Americans “the best condition in every way that has been devised.”26

Two decades later, in 1901, James Hemphill similarly refracted the Vesey conspiracy through the lens of slave fidelity, noting that the plot was foiled by faithful slaves whom Vesey had asked for assistance. Hemphill, in fact, was an even more enthusiastic defender of “the good old days of slavery,” as he characterized the prewar period, than his predecessor was. A quarter century after emancipation, the editor worried that memories of the sectional crisis were quickly fading. Worse still, “the younger generation are growing up to believe that slavery was unredeemed brutality, inconsistent with civilization, and the least said about it the better.”27

Like Dawson and Hemphill, many white Charlestonians highlighted the benevolence of antebellum slaveholders by emphasizing the loyalty that slaves had shown when white men marched off to war. “Behind these magnificent troops,” insisted Citadel professor J. Colton Lynes in 1905, “were millions of contented slaves, who tilled the fields and furnished them food and forage.” In his history of early South Carolina, Edward McCrady contrasted the fidelity slaves had demonstrated during the Civil War with the willingness of their enslaved forebears to assist British invaders during the Revolution. The relationship between masters and the enslaved had improved significantly during the nineteenth century, he held, so much so that when Confederate men left to fight in the Civil War there was not one instance of slave rebellion against the white women and children left behind.28

McCrady may have learned this loyal slave narrative from his old College of Charleston history professor Frederick A. Porcher, who taught generations of young men that slavery was a paternalistic institution. Porcher, who preceded McCrady as president of the South Carolina Historical Society, lampooned the idea that slavery was a necessary evil and confessed in his memoirs that he was inclined to accept the theory that enslaved labor provided the most secure foundation for republican institutions. Like McCrady, Porcher believed that the behavior of the enslaved during the Civil War illustrated slave contentment. He stressed to his students that despite the chaos of the conflict and the provocations of Lincoln and the Union Army, the enslaved never endeavored to break the chains of bondage. Remarkably, however, Porcher’s insistence on wartime fidelity contradicted his own experiences during the war. When approximately eighty slaves fled Lowcountry planter John Berkley Grimball in March 1862, for example, the professor conducted a letter-writing campaign in an effort to recover the runaways.29

By the turn of the twentieth century, the loyal slave trope had become a national phenomenon. Plantation school authors such as Joel Chandler Harris and Thomas Nelson Page crafted stories, often narrated in dialect by aging ex-slaves, that portrayed the Old South as a place of moonlight-and-magnolia romance and loving bonds between master and servant. Fictional mammies such as Aunt Jemima were used to hawk pancake batter mix, and southern newspapers touted the fidelity of ex-slaves in obituaries and coverage of Confederate reunions. “Uncle William is now bowed with age,” reported the Charleston Evening Post of one former body servant who attended the 1899 UCV meeting in Charleston. But he “is as devoted to the memories of the Confederacy as any man who has come to the Reunion.” Three years earlier, the tiny upstate town of Fort Mill, South Carolina, had even erected a monument to slave fidelity.30

Charleston’s Confederate memorialists also kept antebellum debates over slavery alive, regularly lambasting abolitionists, including Harriet Beecher Stowe, John Brown, and the Grimké sisters. In the early twentieth century, UDC member Louisa B. Poppenheim wrote Alexander S. Salley, the secretary of the Historical Commission of South Carolina, for information about Charleston-born abolitionists Sarah and Angelina Grimké. Although reared in a prominent planter family, the sisters—who were the white aunts of Archibald Grimké—rejected slavery and their hometown to become prominent northern activists. “Those women,” replied Salley, a Charlestonian himself, “were unbalanced mentally, morally, and socially, and the capable historical or literary critic of to-day would anywhere regard it as a case of histeria [sic] to see them put down as exponents of the best in the South.” Salley encouraged Poppenheim, who with her sister Mary published the Keystone, a UDC organ, to “kill the myth if you can and stick a steel pen charged with your brightest sarcasm into its carcass if you cannot kill it.”31

White Charlestonians were equally disparaging of Harriet Beecher Stowe and Uncle Tom’s Cabin, which loomed larger in the southern white imagination than perhaps any other book, save the Bible. Stowe’s antislavery novel is “entirely lacking in anything like pure literary taste,” insisted the Charleston Courier in 1869, seventeen years after it was originally released. After the publication of a new edition of Uncle Tom’s Cabin in 1885, the News and Courier urged southerners to read the novel in order to understand how it “caused the South to be placed in a false position in the eyes of the world.” A decade later, Charleston-born Mary Esther Huger raised questions about Uncle Tom’s perfect character in a history she penned for her granddaughter. “A Bishop of our Church, after reading the story, said, ‘if slavery made men such Christians as Uncle Tom, it was a pity, all men were not slaves,’” Huger wrote.32

Nostalgia for the Old South led some Charlestonians to conclude that emancipation had been an unfortunate development. Although Confederate memorialists rarely called for a return to slavery, they often cast the New South in an unflattering light when compared to life before the war. These comparisons had political value. Just as Republican candidates had used unvarnished recollections of slavery as political weapons during Reconstruction, southern whites turned the Lost Cause into a vehicle by which not only to venerate the past but also to critique the present. White remembrances of slavery, in other words, were an effective way to defend Jim Crow laws and practices—measures that Lost Causers believed would curb the problems unleashed by emancipation.33

Citadel professor J. Colton Lynes insisted that free black people in the early twentieth century were worse off than their enslaved forebears. “As a rule, those negroes who are old enough to have experience worth remembering do not hesitate to declare that the state of bondage was far happier,” he argued. Lynes insisted that now most blacks were surly and prone to criminal activities. Ben Tillman focused his ire on one crime in particular: black-on-white rape. Under the civilizing institution of slavery, this outrage had been unheard of, the South Carolina politician suggested in a 1903 speech. Then, turning to the present, Tillman asked, “What is the situation now? Take your morning paper and read it any day in the year, and there is hardly a day in which our sensibilities are not wrought up and our passions aroused or our pity aroused by some tale of horror and woe.” Tillman chose not to speak directly to his preferred method for handling the supposed epidemic of the African “fiend” who, as he put it, lurks around every corner of the South “to see if some helpless white woman can be murdered or brutalized.” But few people who read these words could have had any doubt where Tillman—who was known for his lynching pledge—stood on the question.34

Pitchfork Ben was not alone in using white memories of slavery to justify lynching. Four years earlier, in the wake of the brutal lynching of Sam Hose—a black laborer accused (likely falsely) of murdering a Georgia planter and then raping his wife—a writer to the Charleston Evening Post attributed such crimes directly to emancipation. “In the days of slavery the crime was unknown,” wrote a correspondent calling himself “G.” “Women were left unprotected on a plantation of several hundred negroes; and during the war not a white man [was] within miles. These offenders are from a class that have grown up since the days of slavery, and are subject to no control whatever.” In the absence of southern slavery and its civilizing effect, “G” concluded, the only answer to beasts like Hose was the lynch mob.35

* * * *

BY THE TURN of the century, when Charleston hosted the national UCV convention, local Lost Causers had spent the better part of three decades touting the righteousness of the Confederacy and all for which it had stood. Some northerners, bent on sectional reconciliation, were fooled by this shell game. Union veteran and Massachusetts blue blood Charles Francis Adams Jr., who came to Charleston in late 1902 to lecture to the city’s New England Society, was one. Edward McCrady toured him around the city and accompanied him on a harbor cruise. At the New England Society’s annual banquet, Adams no doubt pleased his hosts by ignoring sectional differences over slavery, focusing instead on disputes over the question of state versus national sovereignty that extended back to the founding of the nation. In his mind, the Civil War was the inevitable culmination of a constitutional conflict, and, as such, both the Union and the Confederacy had been correct.36

Reflecting the reconciliationist temperament of the day, a number of northern and southern newspapers cheered Adams’s address. At the same time, however, several northern dailies, including the New York Evening Post and the Springfield Republican, adamantly dissented. Even Charles Francis Adams had his limits. In the months before Adams’s Charleston visit, McCrady had directed his publisher to send the northerner his two volumes on South Carolina during the American Revolution. After perusing the work, Adams raised objections to McCrady’s theories about slave loyalty during the Civil War. In particular, Adams questioned McCrady’s suggestion that the unwillingness of the enslaved to rise up against their masters reflected the benign nature of antebellum slavery. On the contrary, the former Union officer argued that soldiers like him knew that the enslaved “longed for freedom,” for they flocked to federal lines whenever possible.37

Before the Civil War, white southerners had decried any unflattering characterization of slavery. Such portraits seemed equally threatening at the dawn of the twentieth century—decades after slavery had ended. There was, for one, a generational crisis, as children were now being born to parents who themselves lacked direct knowledge of slavery or the war. “There is an enemy at your door constantly threatening, constantly aggressive . . . injecting into history the untruths which desecrate the memory of your ancestors, those from whom you claim to be descendants,” Major Theodore G. Barker admonished Charleston’s original Sons of Confederate Veterans camp in 1895. “It is a solemn work, and one befitting the worthy descendants of such men, to protect in history the truth that has been handed down to you.”38

The expansion of public education had the potential to make matters worse, since the North was home to most textbook authors and publishers. Would southern children be forced to learn about the Civil War from Union-slanted history textbooks? This fear was so acute in 1890s South Carolina that it appeared to be the only issue—beyond the righteousness of the Lost Cause itself—that could unite the white citizenry, which was deeply divided between supporters of traditional conservatives like Wade Hampton and those of the new, race-baiting governor, Ben Tillman. Although irate over the General Assembly’s decision to give Hampton’s U.S. Senate seat to a member of the Tillman faction, the pro-Hampton News and Courier admitted in 1890 that it agreed “most heartily” with Tillman when it came to the degradation of the Confederacy in textbooks. As Hemphill wrote, “Too frequent reference cannot be made to what Governor Tillman says with so much force in his inaugural address upon the subject of text books for our public schools.” Education, in short, became a chief front in the memory battle over the next three decades.39

Many white southerners sought to impart the proper lessons within the privacy of their own homes. By the end of the nineteenth century, Charlestonian Mary Esther Huger had become frustrated by her granddaughter’s ignorance of the conflict between North and South. “She had never heard any reason given for the civil war, except that the Southerners had Negro slaves, & the Northerners thought they ought to be made free,” explained Huger. So she wrote her own narrative of the Civil War. Others made a point of directing their Lost Cause appeals directly to the southern youth. “My young friends who have grown up since the war, educated from the modern histories, (so called,) I commend this especially to you,” proclaimed Cornelius Irvine Walker in his 1900 Memorial Day address at Magnolia Cemetery. Walker believed that it was older southerners’ duty to preserve the memory of Confederate heroes and martyrs for the benefit of “the younger generation, who should be taught that their fathers fought a good fight, in a pure cause, and fought it well.”40

At the national level, members of the newly formed United Confederate Veterans and United Daughters of the Confederacy launched a movement to make sure their sons and daughters were not exposed to “long-legged Yankee lies.” Responding to the efforts of the Grand Army of the Republic to scrutinize school history textbooks for signs of Confederate sympathies, the UCV and UDC created historical committees that labored to dispel a whole host of northern ideas about, and interpretations of, the war. Sometimes they focused southerners’ attention on simple matters of nomenclature. “Never use the word ‘civil’ in connection with the ‘War between the States,’” Mary B. Poppenheim advised her fellow UDC members in 1902, for it erroneously suggested that the United States was a single whole, rather than a confederation of states. Poppenheim preferred “The Confederate War” or, better yet, “The War between the States.” In other moments, Confederate heritage groups focused on broader issues like the legality of secession. As always, the place of slavery in the history of the war and the South in general loomed larger than any other concern.41

Charlestonians played an outsized role in this memory campaign. Native sons Ellison Capers, known as the Orator Laureate of the Lost Cause, and Stephen D. Lee were leading members of the UCV Historical Committee. Even more influential was Mary B. Poppenheim. Descended from a prosperous planter family, Poppenheim had learned as a child to love the Confederacy. Her father, a veteran of Hampton’s Legion, settled his family in Charleston after the Civil War, where he became a successful merchant and active participant in local Confederate groups. Poppenheim inherited his enthusiasm for the region’s past, eventually becoming an avid student of American history while at Vassar College in the 1880s. After returning to Charleston, she joined the LMAC and helped to found the city’s United Daughters of the Confederacy chapter. One of the earliest women accepted as a member of the South Carolina Historical Society, Poppenheim wrote and edited books and chapters about the Civil War and the UDC. Over the next quarter century, she served as president of South Carolina’s UDC division and president-general of the national organization, chairman of the national UDC committee on education, and UDC historian at the local, state, and national levels. Most important, with the help of her sister Louisa, she produced a monthly women’s journal, the Keystone, from 1899 until 1913. The UDC’s official organ in North Carolina, South Carolina, and Virginia, the Keystone reached women across the South and as far away as California and Maine. Through her UDC efforts and Keystone stewardship, Poppenheim did as much to popularize the cult of the Lost Cause as any person in the early twentieth century.42

Charleston native Mary B. Poppenheim served as president-general of the United Daughters of the Confederacy and published the Keystone, a monthly women’s journal that served as the group’s organ for the southeastern states.

Poppenheim was one of several Daughters who redirected the UDC toward promoting a southern interpretation of the war in textbooks at its fourth annual meeting, held in Baltimore in 1897. She drew the members’ attention to a recent publication, Southern Statesmen of the Old Régime, written by a University of the South professor, which offered unflattering portraits of John C. Calhoun and Jefferson Davis. The textbook “tends to prejudice students against these prominent expounders of the doctrine of State’s rights,” she concluded. The UDC’s original 1894 constitution had pledged “to collect and preserve the material for a truthful history of the war between the Confederate States and the United States of America,” she reminded the delegates, yet southern minds were in danger of being “poisoned at the very fountain heads of learning.” Two years later, in her Keystone report on the UDC annual meeting in Richmond, Poppenheim asserted that “no better work can be done by the women of any community than to preserve the facts of history pure and free from prejudice. . . . Truth, at any cost, should be their watchword.”43

Under Poppenheim’s direction, the South Carolina UDC Historical Committee sought to counter northern interpretations by collecting, preserving, and publishing historical manuscripts about the war and encouraging southern historians to write their own accounts of the conflict. As she reported at the state UDC meeting in 1902, the committee also prepared programs of study to be used by individual chapters across the state, including one on the history of American slavery, which proved especially popular. Seven years later, the Keystone published outlines of several of its historical programs, which de-emphasized slavery as a cause of the war while also suggesting that emancipation in the South was inevitable. Praising the work of the Historical Committee, state UDC president Harriet S. Burnet held that its efforts were the natural complement to the monuments that Confederate women had been busily erecting across the southern landscape: “Let every woman in the South see to it that the heroism of our beloved South land be not only written in bronze and stone, but let a historical record be made to be read of all men.”44

In addition to her work on behalf of the Historical Committee, Poppenheim used the Keystone to keep UDC members in Virginia, the Carolinas, and elsewhere abreast of other work the group was doing to protect the Confederate legacy. Like the News and Courier, the journal functioned as a clearinghouse for Lost Cause events and ideas. In 1904, Poppenheim reported on a new state initiative to supplement what South Carolina children learned about the Civil War in school by organizing auxiliary youth chapters under the guidance of local parent chapters. As older southerners passed away, the UDC had to ensure the next generation was armed with a proper understanding of the conflict. At the local level, the Keystone reported, Charleston’s UDC chapter maintained the Confederate Museum, which it actively encouraged school groups to visit, and sponsored an essay contest “to awaken in the children of this generation an interest in the history of the ‘Lost Cause.’” The committee that organized the contest, which included Poppenheim, put up $10 in gold as a yearly prize and, unsurprisingly, selected the causes of South Carolina secession as its first subject.45

Poppenheim and her UDC colleagues kept careful watch of the textbooks used in the state’s public schools as well. In early 1905, the Historical Committee sent every chapter in the state a circular that covered a number of topics, including the textbook question. In addition, the Keystone identified appropriate textbooks and histories as well as books that the UCV viewed as biased against the South.46

At the annual meeting of the South Carolina division of the UDC, held in Camden in December 1903, Poppenheim focused the Daughters’ attention on one objectionable text in particular: Edward Eggleston’s A History of the United States and Its People. Assigned in numerous southern schools, including those in Charleston, Eggleston’s textbook held that slavery caused the Civil War. In the years that followed, Mary, her sister Louisa, and other UDC members led a crusade to remove Eggleston’s book, and other unfair histories, from South Carolina classrooms. The Historical Committee circulated lists of acceptable and troubling books to all UDC chapters, and members pressured local school districts and principals to adhere to them.47

In late 1905, Poppenheim, who was now president of the state UDC division, cheerfully informed her fellow Daughters that the public schools in Columbia had decided to replace Eggleston’s history with a UCV-approved book. The Poppenheim sisters’ work eventually paid the same dividends at home. In October 1907, Charleston School Superintendent H.P. Archer announced that the city had exchanged Eggleston’s history for Waddy Thompson’s A History of the United States. The latter textbook subordinated slavery to states’ rights as a cause of the war, while succinctly and vaguely concluding that “the underlying cause of the war between the sections was the conflict of Northern and Southern interests.”48

Several years later, in 1914, Mary B. Poppenheim felt comfortable declaring mission accomplished on at least one front of this memory campaign. Speaking as national chair of the UDC’s Committee on Education to an audience in Savannah, Georgia, Poppenheim said that she was frequently asked what she thought about endowing chairs in southern history at southern colleges and universities. Having proclaimed at the 1897 UDC convention that the “fountain heads of learning” were poisoned, she insisted in 1914 that they were now pure. Two decades of UDC work “has borne rich fruits for the harvests of truth,” Poppenheim concluded. Now, we “must look elsewhere for the contamination.” Three years later, at the twenty-third annual UDC convention in Dallas, Poppenheim was again brimming with optimism. Holding up a recent Yale University Press announcement for the publication of a fifty-volume history of the United States, the chair of education underscored the fact that three of the four men writing the volumes covering the years 1861 to 1865 either had been or were employed at southern colleges and universities.49

By this point, state officials in Columbia were lending a hand. Acting upon the request of the South Carolina state superintendent of schools, Mary C. Simms Oliphant updated an 1860 history of the state written by her grandfather, Charleston poet and writer William Gilmore Simms. The state adopted The Simms History of South Carolina in 1917, and, over the course of nine editions, it remained an official South Carolina textbook until 1985. For nearly seventy years, countless South Carolinian schoolchildren—black and white, upstate and Lowcountry—learned about the history of their state from one of the Old South’s leading proslavery apologists and his descendant.50

One measure of the success of this Confederate memory work in South Carolina was the children’s catechism produced by the state division of the UDC. In the first three decades of the twentieth century, UDC divisions in North Carolina, South Carolina, and Texas, as well as the national organization, produced catechisms modeled on Christian books of instruction, which laid out the basic tenets of faith in a simple, often question-and-answer format. Most of these catechisms approached slavery through the standard litany of evasions (it was not the cause of the war), excuses (the South was not to blame for it), and mischaracterizations (it was a benevolent system of caring masters and devoted servants). But South Carolina’s version, produced by Mrs. St. John Alison Lawton around 1919, entirely ignored the region’s history of slavery, the slave trade, and debates about what caused the Civil War. Those subjects and questions, in South Carolina at least, were settled.51

* * * *

ON JUNE 5, 1916, just weeks after its fiftieth anniversary celebration, the Ladies’ Memorial Association of Charleston, the city’s original Confederate memory organization, gathered for its annual meeting at president Videau Legare Beckwith’s Church Street home. Beckwith told the group that she had received a letter from Mary B. Poppenheim, who as an LMAC officer was also in attendance that day. In her letter, Poppenheim reported that she had recently stumbled upon an account of the 1865 Martyrs of the Race Course ceremony published in the Christian Herald. Although born, raised, and still living in the city, Poppenheim had never heard of the 1865 Decoration Day service, so she asked Beckwith, also a native Charlestonian, what she could find out about the event. “I regret that I was unable to gather any official information in answer to this,” Beckwith responded. The fact that two leading Charleston women, both of whom were devoted to Civil War commemoration, knew nothing of their city’s first Decoration Day is telling: white Charleston’s memory of the war did not extend to the festivals of freedom that took place in 1865. The Lost Cause, like all manifestations of social memory, was a selective approach to the past. It involved forgetting as well as remembering.52

Knowledge of the Martyrs of the Race Course ceremony, to be fair, had faded fast in many places. After Ladies’ Memorial Associations across the South flocked to Confederate graves in 1866, northern newspapers reminded their readers that this custom was initiated by James Redpath and the black citizens of Charleston. But by 1868, when the Grand Army of the Republic called for its members to honor the federal dead in an annual May ceremony, numerous observers insisted that the northern veterans organization was trying to usurp a tradition begun by white southern women. The debate over the origins of Decoration Day lingered for decades.53

Poppenheim, Beckwith, and other early-twentieth-century Confederate memory stalwarts most certainly recalled another memorial service held at the Washington Race Course. On April 11, 1902, Wade Hampton died, bringing the state to a virtual standstill. For many South Carolinians, the state’s Redeemer general rivaled Robert E. Lee as the embodiment of the Lost Cause. In recognition of this native son, Poppenheim and her fellow Daughters hosted a memorial with hundreds of mourners one day after Hampton’s death. The services were conducted in a new auditorium, which had been built for the South Carolina Inter-State and West Indian Exposition, a world’s fair being held at the Washington Race Course and the surrounding area in 1901 and 1902.54

Soon after, South Carolinians started raising money to build a more permanent tribute to Hampton. While many state residents hoped to install a monument to the Confederate hero on the capitol grounds in Columbia, Charlestonians thought that their city was a better location. In the end, however, the Columbia site won out.55

White Charlestonians eventually made their peace with the Columbia monument to Hampton, which was installed in 1906, but they also built a memorial of their own, renaming the Washington Race Course in Hampton’s honor in 1903. This, in some ways, was the city’s final act of Redemption. The site of a black-built tribute to the loyalty of Union soldiers in 1865, the old racetrack became the symbolic home of loyalty to white supremacy. And despite the sizable black population in adjacent neighborhoods, Hampton Park swiftly became a whites-only space.56