ON FEBRUARY 13, 1906, BOSTON MINISTER GEORGE F. Durgin sailed out of New York City amidst a rainstorm. Clearer skies greeted his ship four days later as it steamed into Charleston Harbor on Saturday morning. Despite the inviting weather, the crew advised the passengers not to disembark early, as residents got up late. After spending the day wandering around the sleepy city, it appeared to Durgin as if the city never awoke at all. The city’s drowsy atmosphere was compounded by its dilapidated appearance. Apart from several public buildings and one gorgeous residential neighborhood, Charleston seemed entirely neglected by its occupants. “Paint is wanting everywhere; churches need renovation,” Durgin observed. “It looks as though the city had slept right through the earthquake of twenty years ago, and was waiting patiently for the resurrection.”1

Yet if any place deserved to rise from the dead, Durgin suggested, it was Charleston. There were so many interesting things to see in the old city. Durgin’s first stop was the grave of John C. Calhoun. Too bad that Calhoun had fatally wed “all his magnificent powers to a doomed and unrighteous cause,” he concluded. Durgin also visited St. Michael’s Church, noting that he followed in the footsteps of George Washington and Robert E. Lee, as well as what he thought was the city’s slave market. Simultaneously fascinated and troubled by Charleston’s many Lost Cause memorials, he wrote that “there are Confederate monuments, with Confederate inscriptions and abounding Confederate sentiment.”2

When Henry James toured Charleston the previous February, he had been struck by many of the same things as Durgin: St. Michael’s Church, the quiet city streets, its evocation of the past. To the American author, who had spent decades living overseas, Charleston seemed not so much asleep as empty. Comparing Charleston to a “vacant cage which used in the other time to emit sounds . . . audible as far away as in the listening North,” James wondered how, in such a great society, “can everything so have gone?” Could it be that slavery had been “the only focus of life” and with its abolition no other interest was left? “To say ‘yes’ seems the only way to account for the degree of vacancy,” he reasoned.3

Even so, the beautiful, noble old homes captured his imagination. “I had to take refuge here in the fact that everything appeared thoroughly to antedate, to refer itself to the larger, the less vitiated past that had closed a quarter of a century or so before the War,” James concluded. Charleston’s refuge, he implied, lay in its early years. Passed over by the industrial transformations of the New South, Charleston teemed with magnificent old buildings, which despite (and in some ways because of) their state of disrepair evoked a distant, aristocratic past. For northern tourists like Durgin and James, the city beckoned as a window into a foreign world, a stepping-stone back in time.4

* * * *

THE TRANSFORMATION OF Charleston into a tourist mecca was a long one, and not, as it may seem to visitors today, an easy development for a city so steeped in history. The seeds of its eventual success were planted in the years after the Civil War, when a full-blown tourism industry began to take off in the South. Before the war, wealthy planters took their families to the springs of Virginia during the summer, and some northerners, primarily journalists, traveled to the South to document the region’s issues. These pilgrimages resumed once hostilities had ceased, and by the 1880s the South had gone from a problem to be explained to a destination to be enjoyed. Part of this change had to do with new patterns of travel. Once the provenance of the elite, travel was democratized during the second half of the nineteenth century. Many northern, middle-class families could now afford tourist excursions, and employers increasingly granted paid vacations.

There was also the special allure of the South, which travel writers and resort owners trumpeted in promotional literature. The region offered salutary benefits—warm weather, mineral springs—for the sick and exhausted. For those unhappy that former stomping grounds like Saratoga had been discovered by the masses, southern locales provided exclusivity. Finally, for individuals suffering from the ennui that accompanied life in the standardized, uniform North, the South presented opportunities for unique experiences, chances to encounter distinctive people and places—unusual foliage, an old plantation, or even an aging Confederate veteran.5

Charleston was a tourist attraction during these years, but it certainly was not the primary one. Southbound travelers tended to patronize the spas of Virginia and West Virginia or make their way to the mountains of western North Carolina and eastern Tennessee, viewed as a frontier-like retreat from the modern world. Many others chose the eastern coast of Florida, the most popular southern destination in the late nineteenth century. This growing tourist trade all but bypassed Charleston. Most northern visitors to the city did not make it their final destination; Charleston was simply a stopover en route to and from Florida.6

In 1873, Massachusetts-born journalist Edward King did visit Charleston. He immediately recognized that the past exerted a great deal of power in the city. In contrast to “our new and smartly painted Northern towns,” King wrote, “in Charleston the houses and streets have an air of dignified repose and solidity.” Oliver Bell Bunce, a New York journalist writing for Appleton’s Journal’s “Picturesque America” series, visited Charleston in the early 1870s, too. “It is quite possible,” Bunce observed, “the somewhat rude surface and antique color of the brick houses of Charleston would fail to please the taste of Northerners reared amid the supreme newness of our always reconstructing cities.”7

But Charleston was picturesque to those who knew where to look and how to appreciate it—a project these writers’ travelogues helped facilitate—providing just the contrast and novelty many northern travelers sought. Constance Woolson, who described the city for Harper’s in 1875, delighted in its ancient homes and gardens, which had not “been swept away by the crowding population, the manufactories, the haste and bustle, of the busy North.” Woolson, King, and Bunce all waxed rhapsodic about the ruins they stumbled upon, reliquaries of a former civilization or, like the many plantations outside the city, “sorrowful ghosts lamenting the past.”8

Charleston appealed as a vacation spot the same way a quaint New England village did, as a preindustrial refuge from modern life. According to these writers, the plantations outside of the city existed to enchant. Every spring, Woolson observed, northern tourists, stopping over in Charleston on the way home from Florida, visited Magnolia Plantation, which had burned during the war but whose “bewitchingly lovely” gardens were opened to the public in 1870. Many lost themselves in “the glowing aisles of azaleas.” Bunce was also taken with Magnolia. “This place is almost a paradise,” he exclaimed, overwhelmed by how the “tropical splendor of bloom” combined with the “overgrown pathways, unweeded beds, and the blackened walls of the homestead” to create a scene of both beauty and desolation.9

But race and the vestiges of slavery made Charleston distinct from northern destinations. At Magnolia, where freedmen who lived and worked on the plantation guided visitors through the grounds, Bunce and his party were welcomed by an elderly man “with all the dignity and deportment of the old school.” Edward King found that Lowcountry blacks “still maintain their old-time servility toward their former masters” and that whites, when asked if their former slaves had changed much in manners or habits since emancipation, answered with an emphatic, “No!” Ex-slaves exuded an exoticism that proved irresistible to northern white travelers. In both the city and the surrounding countryside, blacks were a spectacle, their sartorial preferences for “gay colors” and “extravagant” and “gaudy” apparel a wonder to these northern eyes. Though it may have been low and degraded, African American character ultimately offered “an endless source of amusement.”10

From the beginnings of postwar Charleston tourism, then, African Americans were a tourist attraction, like the antiquated churches and plantations that made the area so unique. White visitors saw them—barely removed from an Old South setting, if at all—as a picturesque, even entertaining, aspect of the local scenery. These portraits of blacks functioned like magnolias and Spanish moss, as “a signifier of the Old South” to northern tourists not only craving novelty but also taken with fantasies of white supremacy and black docility. In this way, the remnants of slavery, whether human or architectural, helped foster sectional reconciliation, their aesthetic attributes deflecting from their political content. Oliver Bunce wrote that his outing to the plantations along the Ashley River united his traveling companions—a varied group of northerners, southerners, and Englishmen—in a spirit of amicable camaraderie, defusing the sectional tensions that still smoldered in the 1870s: “The political elements composing the party were as antagonistic as possible; but, regardless of North or South, the Ku-Klux, or the fifteenth amendment, we gathered in peace.”11

What stands out most about this northern travel literature is the way that it differs from local guidebooks of the same era. The Charleston City Guide, issued in 1872, and the Guide to Charleston, published in 1875 and again in 1884, barely acknowledged that blacks were a part of the area’s past or present at all. These locally produced books also kept the institution of slavery at arm’s length, never alluding to its role in making possible Charlestonians’ “accumulation of great wealth” or in inciting the Civil War. More generally, these Charleston tourism tracts contained few, if any, of the colorful descriptions of plantations or even contemporary African Americans that northern travel writers provided to their readers. Unlike King, Bunce, and Woolson, in other words, early Charleston tourism writers seemed unaware of the fact that visitors might be drawn to former slaves and plantation ruins as alluring reminders of days gone by. Instead, they simply pointed out the places within the city that tourists should put on their itinerary—from religious sites and government buildings to educational institutions and public parks.12

As local guidebooks attest, by the 1870s and 1880s a few Charlestonians, at least, appreciated that some of their city’s charms were worth promoting. The natural calamities that brought the Lowcountry to its knees, however, did not make the prospect easy. An 1885 hurricane and the 1886 earthquake caused millions of dollars in damages, funneling scarce resources into rebuilding efforts. Still, enterprising Charlestonians knew an opportunity when they saw one. Frank Dawson, Frederick W. Wagener, and other businessmen organized Gala Week for November 1887, deciding to use the recent disaster to their advantage. This “monster excursion,” as Dawson called it, would bring in throngs of tourists to witness the city’s post-earthquake progress, to see that it was now “a bright, clean, vigorous city, full of life and activity.” He was right. By the middle of Gala Week, hotels were so overcrowded that proprietors turned billiard tables into makeshift beds.13

If Charleston was going to attract more tourists, it needed better amenities. In 1888, Frederick W. Wagener led a campaign to build a new hotel at the Battery but failed to raise the necessary funds. Four years later, Governor Ben Tillman’s dispensary law went into effect, limiting the sale of alcohol to state-run dispensaries. While Charlestonians ignored the law, drinking at home or in “blind tigers,” early versions of speakeasies, the statute proved a thorn in the side of tourism boosters since hotels and restaurants could not satisfy patrons desiring a drink.14

Despite these setbacks, enthusiasm for tourism ran high among Charleston’s New South boosters, and the end of the nineteenth century gave birth to several major efforts to attract visitors to the city. The Young Men’s Business League organized a South Carolina reunion of Confederate veterans in 1898, which in turn inspired a larger campaign to attract the 1899 national meeting of the United Confederate Veterans, considered a resounding success. The 1901–2 South Carolina Inter-State and West Indian Exposition represented a bright spot for tourism as well, though the fair ultimately failed to pay its own bills. Owing to a combination of problems—including local indifference, inclement weather, and black opposition—the Exposition was the first of its kind to be put into receivership.15

Henry James’s 1905 trip to Charleston—where, as he wrote, “history has been the right great artist”—came on the heels of these events. Like so many northern travelers who had visited Charleston since the end of the Civil War, James was smitten, almost despite himself. Even though the Old South that James glimpsed in Charleston “was the one that had been so utterly in the wrong,” he preferred it to the New South, which had “not yet quite found the effective way romantically.” Looking around the city, he concluded “that the South is in the predicament of having to be tragic, as it were, in order to beguile.”16

* * * *

CHARLESTON TOURISM BOOSTERS happily played to this beguilingly tragic aesthetic by showcasing their majestic mansions with peeling paint and unkempt gardens. Most of them recoiled, however, at visitor interest in artifacts and sites that spoke—or at least appeared to speak—to the human tragedy of slavery too directly. Northern tourists, for one, clamored to take home their own slave badges, relics unique to Charleston’s antebellum system of urban slavery. Used as early as the 1750s, slave badges—pieces of metal stamped with the year of issue, a badge number, and an occupational category—identified Charleston slaves hired out by their owners to work for someone else.17

Charleston required slaves hired out by their masters to carry or wear metal slave badges such as these. At the end of the nineteenth century, local merchants began hawking badges, many fake, to tourists.

Demand for the now obsolete tags was not an immediate postwar development, as white Charlestonians, and some blacks, at least, appear to have forgotten about their existence. A News and Courier article in 1889 reported that “a lot of old brass pass badges which were used by slaves before the war” had been obtained by a stockbroker from an elderly black man, an event that prompted much talk around the city. Six years after the stockbroker’s discovery, some collectors in Charleston concluded that the badges might appeal to relic seekers. In 1895, a vendor placed a wanted ad in the Evening Post, soliciting Confederate money, Confederate buttons, and slave badges, presumably to sell them as souvenirs.18

By the time the Exposition opened in 1901, the tourist market for slave badges—both real and counterfeit—was roaring, a development that did not sit well with some. Daniel Elliott Huger Smith, a Confederate veteran who was a leading member of the South Carolina Historical Society from the 1890s until the early 1930s, denounced this “most ridiculous trade” in which “very ordinary bits of brass” were sold as slave badges at steep prices. “Doubtless many have been dispersed over the North,” he ventured, “as curiosities of slavery.”19

The most detailed report of this activity came from John Bennett, an Ohio-born artist and writer who himself arrived as a tourist in 1898 and never left. Four years earlier, Bennett had vacationed at Salt Sulphur Springs, West Virginia, where he befriended the Smythe family of Charleston—Augustine, his wife, Louisa, and their daughter, Susan. After a series of illnesses affected his health, Bennett chose to recuperate in Charleston. By 1899, John and Susan were engaged.20

Like so many northern visitors, Bennett was taken with the city and its environs. Of Medway, a plantation outside the city where the couple spent time before their wedding, Bennett wrote that it was “the pathos and sadness that hangs over everything in this land that wrings me closest [to] the heart.” When, a few months before the couple’s April 1902 wedding, Bennett discovered that downtown shops were pedaling slave badges—most of which were counterfeits—to tourists in the city for the Exposition, he was naturally interested. But after talking to a few of these unsuspecting visitors, combing through Augustine’s law books, and consulting any number of “the genuine old negro of the genuine old days,” Bennett grew indignant. Both the buyers and sellers earned his scorn—the former for their mistaken impressions of the peculiar institution, the latter for catering to such notions with fake artifacts and fake history.21

In a News and Courier article intended to set the record straight, Bennett’s sarcasm was palpable. He took a jab at tourists, who were “full of innocent Northern eagerness to carry home a trophy, some trophy of ‘the old, old South’ of the days when every morning made a mock of the Fourth of July with the re-echoing and explosive cracks of the ‘nigger driver’s whip,’ when all the swamps were full of runaway slaves.” Trinket-shop owners on King Street obliged this curiosity, he wrote, by offering what they claimed to be slave badges but were really nothing more than tags for railroad lockers. Rather than detailing the real purpose of the badges in the hiring-out system, these unscrupulous entrepreneurs told tourists that they were substitutes for brands that allowed owners to claim runaway slaves. Some dealers went so far as to imply that the tags had been affixed to slaves’ bodies with safety pins or metal rings.22

Bennett lay part of the blame for the misinformation surrounding slave badges at the feet of white Charlestonians, especially the younger generation. It knew nothing of slavery and the Old South and could not refute the tall tales spun by King Street dealers. He also had harsh words for Harriet Beecher Stowe, the South’s perennial scapegoat. The average tourist, he complained, was proud of his “precious relic of ‘the old regime’ so maligned by Harriet Stowe, who must stand to the end responsible for many just such frauds as this,” thus proclaiming the faked slave badges—in an extraordinary leap of logic—one of Stowe’s many odious legacies.23

In addition to the slave badges, local businesses peddled postcards that spoke to slavery and the slave trade. One early-twentieth-century postcard featured a picture of buzzards and a lady in front of the City Market stalls, described as “a part of the Old Slave Market,” a common but somewhat confusing term used to describe the open-air sheds. Although slaves had worked in the City Market stalls—hawking meat, fish, and produce—human chattel had not been sold there. Intentionally or not, postcards like this one led some tourists to mistake it for a slave auction site. After exploring the complex in 1906, Illinois-born poet Vachel Lindsay wrote that he felt like he was “being stifled in bloody tiger lilies.” On the one hand, Lindsay found “packed in those long stalls the ghosts of a wonderful civilization.” On the other hand, “there is a clanking of chains and a rattle of angry skeletons.” Visitors in this period could also buy postcards that featured an actual slave market, the former Ryan’s Mart at 6 Chalmers Street. A 1920s card of this building—which was referred to interchangeably as the Old Slave Mart and the Old Slave Market in the early twentieth century—proclaimed it “a dilapidated but quaint little structure” that “is all that remains of the once flourishing traffic in slaves.”24

This postcard was somewhat exceptional, as forthright discussion about the city’s slave-trading past was rare. An updated 1911 Guide to Charleston, S.C., which drew on the earlier 1875 and 1884 versions, listed the “Old Slave Market, So-Called” at 6 Chalmers Street in its street-by-street narrative of historic sites. Its very inclusion seems to have been a result of tourist interest. “Many visitors to the city,” the text read, “particularly those who have imbibed the traditional prejudices against old time Southern slavery, enquire for the tourists’ traditional ‘Slave Market.’” “As a matter of fact no such market existed in the city,” asserted the guidebook, penned by Confederate memory stalwart Cornelius Irvine Walker. The Guide to Charleston, S.C. allowed that slave brokers did, in fact, conduct sales from several buildings in “the neighborhood of Broad, State and Church Streets,” but it nonetheless held that “no general market” for the sale of slaves existed. What’s more, Walker held that “most of the Southern owners of slaves never sold them, and the workers on the various plantations passed by inheritance from father to son.”25

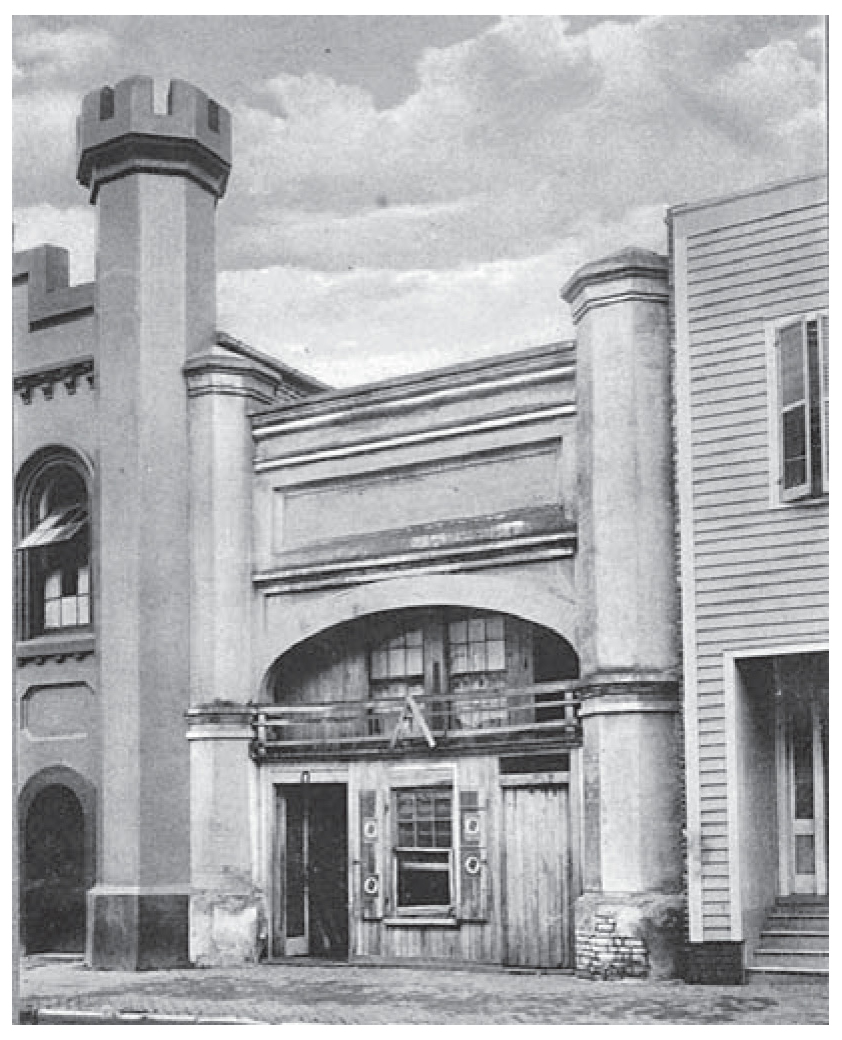

Ryan’s Mart at 6 Chalmers Street was the city’s leading slave-trading site in the late 1850s and early 1860s. To the consternation of some whites, it became a popular tourist destination in the early twentieth century.

The eagerness of northern tourists to confront the slave past in its less sanitized form surprised and annoyed Walker and some of his fellow residents—though not all, as the thriving business in slave badges and postcards suggests. Tourist interest threatened not only to air their ancestors’ dirty laundry in public but also to spoil the feeling of sectional reconciliation many tourist encounters were intended to nurture. Yet controversy sold. Indeed, Civil War prison camps became tourist attractions in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, at least in part because of their divisive nature. In 1899, a group of northern businessmen purchased and moved a Confederate prison from Richmond, Virginia, to their hometown of Chicago, where they operated the Libby War Museum for the next decade. Southerners also capitalized on the commercial potential of Civil War prisons. In the mid-1890s, the residents of Thomasville, Georgia, seized on the town’s proximity to the infamous Andersonville Prison as an economic boon. The Thomasville Review advertised Andersonville as a “must see” site that was a “Mecca for thousands of tourists each year.”26

* * * *

NOT ALL CHARLESTON tourists, of course, were white. “The number of excursionists that are brought to Charleston every week would populate a large town,” reported the Indianapolis Freeman, quoting an unidentified black Charleston newspaper in 1890, which stated that African Americans were among this tourist throng, even though “they cry poor.” Where these tourists were from, and what they did and visited once they arrived, is not entirely clear. Did they buy slave badges, real or other wise? Did they read the same guidebooks as white visitors?27

The city was not overly interested in the African American tourism market during these years, but it did attempt to attract black tourists to the Exposition in 1901–2. The effort largely fell flat. As a writer for a black Washington, D.C., newspaper attested, Charleston did not necessarily strike African American visitors as charming. On a trip to the city in the run-up to the Exposition, he was asked by a local if he liked Charleston. “Presumably,” he quipped, “the asker of any such question never expects to get a frank and honest expression of opinion from the person to whom it is addressed.” To this tourist, Charleston seemed hopelessly hidebound by tradition, a charge he leveled against both white and black residents. He found the deference to tradition off-putting. The “slowness with which they move and the tendency not to do things simply because it is not custom,” he complained, “unnerves me and irritates me almost beyond expression.”28

One wonders if this writer took issue with the area’s racial customs, for some travelers certainly did. William D. Crum, assistant commissioner of the Negro Department at the Exposition, observed that poor train facilities prevented many African Americans from other cities and states from attending the world’s fair. The New York Age heard reports that “all sorts of discriminations were permitted on the Exposition grounds” and concluded that black tourists would have numbered in the thousands had these issues been addressed.29

Still, some African Americans ignored the inconveniences of Jim Crow travel—which included the fact that the first hotels catering to black visitors did not open until the second decade of the twentieth century—and put Charleston on their itinerary. One man writing for the Indianapolis Freeman in 1905, who signed his essay as simply a “Wanderer,” insisted that “historic old Charleston is worth the price of a visit.” In stark contrast to the Lost Cause vision pedaled by local chapters of the UDC and UCV, he urged an emancipationist reading of Civil War sites in the area. Fort Sumter, argued the Wanderer, demanded attention. This was so because it “is almost as closely associated with our emancipation as the proclamation itself.” He also reminded readers that the harbor in which the fort sat had provided the backdrop for Robert Smalls’s daring escape aboard a Confederate supply boat. According to the Wanderer, Charleston Harbor was to be celebrated for its connection to black freedom.30

The Wanderer also commented upon the Calhoun Monument, noting that the city had outgrown the statue, “as the greater portion of it is now in the rear of the man in bronze,” an accurate assessment of the city’s northward population shift. But he intended the observation metaphorically as well: “As the city has outgrown the monument so too this great people are outgrowing many things for which Mr. Calhoun stood.” Rather than condemning the statue as a symbol of both slavery and segregation, as local blacks were inclined to do, the Wanderer viewed the memorial as a relic from a bygone era. As proof, he listed black Charlestonians who excelled as teachers, businessmen, ministers, and lawyers. Signing off with a plea for all to promote goodwill between the two races in the city, the Wanderer’s optimistic reading of the Calhoun Monument would surely have struck some black residents as naive.31

A number of leading African Americans visited Charleston in the early twentieth century, too. In 1906, Archibald Grimké, his brother Francis, and three other well-known black South Carolinians who had moved north came back home. They rode a trolley through the center of the city and visited several historical sites, including Calhoun’s tomb. A decade later, just after local black activists founded the Charleston chapter of the NAACP, W.E.B. Du Bois traveled to the city. Mamie Garvin Fields was part of the committee that gave the black scholar and reformer what they thought of as the “grand tour.” They drove a car around town, visiting the old Custom House and the Old Slave Mart, among other sites. As Fields later recalled, “Most of those places that we showed off with all our city pride had to do with slavery, which brought our people to South Carolina in the first place.” Du Bois, however, was not interested in seeing these vestiges of the Old South. “All you are showing me is what the white people did,” he announced at one point. “I want to see what the colored people of Charleston have built.” His guides then took him to the black YMCA and YWCA, but Du Bois dismissed them as the outposts of national organizations and chided Fields and her colleagues to do more.32

Du Bois was more charitable toward Charleston’s black institutions in an editorial he penned for the Crisis not long after his trip. “Mighty are the churches of colored Charleston,” he proclaimed. And as he reconstructed his visit to the capital of American slavery, Du Bois found that human bondage permeated his memories. “Between her guardian rivers and looking across the sea toward Africa,” he wrote of the city, “sits this little Old Lady (her cheek teasingly tinged to every tantalizing shade of the darker blood) with her shoulder ever toward the street and her little laced and rusty fan beside her cheek, while long verandas of her soul stretch down the backyard into slavery.” He saw slavery’s shadow in black churches such as St. Mark’s Episcopal Church, which had been “softened with the souls of fathers and grandfathers who knew Cato of Stono, and Denmark Vesey.” While resting “in the quiet reason of Plymouth Church,” founded by former slaves after emancipation, Du Bois looked across town “to the white tower of St. Michael’s, topping a church of another and seemingly lesser world where a slave once did the deed of a man.”33

* * * *

THE REAL PUSH to attract white tourists to Charleston came after World War I. The war itself proved instrumental, halting American tourist traffic to Europe and redirecting it toward domestic resorts. The advent of automobile tourism also helped, since formerly inaccessible places—and Charleston, with its minimal rail service, was certainly among them—awaited discovery by the adventurous motorist. But the first task on this front was improving the region’s dangerous and at times incomplete roads. Formed in 1921, the South Atlantic Coastal Highway Association spearheaded the good roads effort in the Lowcountry, planning an Atlantic Coast Highway that linked Wilmington, North Carolina, to Jacksonville, Florida, and that passed through Charleston. The project was completed by the end of the decade, the peninsula now connected to the Sea Islands, beaches, and plantations that surrounded it by bridges over the Ashley and Cooper rivers. Easier travel to outlying plantations was especially important, as many tourists hoped to take in the famous “flower gardens,” the common term for area plantations, during their stay in Charleston.34

Thomas Stoney, elected mayor in 1923, made tourism a priority from his first days in office. He informed Charlestonians in his inaugural address that he would promote the city as a tourist resort in every possible manner. The next year, he proclaimed Charleston “America’s Most Historic City,” while at the same time advocating for the modern amenities a thriving tourism industry demanded—paved streets, electric lights, an improved rail station, and, over time, a new airport, a city golf course, and a yacht basin. Charleston welcomed two new luxury hotels in 1924. The first, the Francis Marion, sat at the western edge of Marion Square and stood as a testament to the changing order in Charleston. A group of local investors bought the land and raised the $1,250,000 needed to complete the 312-room structure. The Fort Sumter Hotel, which could accommodate 350 guests, welcomed its first visitors early that summer. Built on the Battery, the spot Frederick Wagener had coveted back in 1888 and deemed holy ground by some, the hotel provided vistas of Charleston Harbor and Fort Sumter.35

Private initiatives complemented municipal efforts to turn Charleston into a tourist resort. For the Society for the Preservation of Old Dwellings (SPOD), however, the immediate goal was not to show off the city’s treasures, but simply to save them. Organized by a coterie of elite Charlestonians, the SPOD looked around the city with growing alarm. The encroachment of modernity, in addition to years of neglect born of the aristocracy’s relative lack of capital, endangered some of Charleston’s grandest and most historic homes. In April 1920, Susan Pringle Frost, the group’s first president, gathered together twenty-nine women and three men to stop the demolition of the Joseph Manigault House, located not too far from Marion Square. This excellent example of Adamstyle architecture, which had been built in 1802–3 for rice planter Joseph Manigault, was to be replaced by automobile garages. The Manigault House was not alone. By the end of the decade, the SPOD had also turned its attention to saving the Heyward-Washington House, which sat next to Cabbage Row—rechristened “Catfish Row” by DuBose Heyward in his 1925 novel Porgy.36

To rescue these homes and return them to their former glory, the women of the SPOD raised money, donated furniture, and educated the public about the importance of maintaining Charleston’s distinctive architectural treasures. In their personal quest to maintain the Miles Brewton House—the residence that had dazzled Bostonian Josiah Quincy back in 1773 and later became the Pringle ancestral home—Susan Pringle Frost and her sisters not only led tours but also raised revenue by renting rooms in the winter to visiting northerners. The lengths to which SPOD members went to salvage homes sometimes strained the limits of good sense. In 1922, Nell Pringle, vice president of the SPOD and Frost’s cousin by marriage, convinced her soon-to-be-unemployed husband to assume the debts of the Manigault House, which totaled $40,000, placing a considerable burden upon the family of eight.37

A postcard, ca. 1901, of the Miles Brewton House. Preservationist Susan Pringle Frost and her sisters rented out rooms and led tours to raise money to maintain this double house on lower King Street.

This early preservation movement also contributed to the whitening of the peninsula. As was true across the rest of the Jim Crow South, segregation, racial violence, and declining economic prospects drove many black Charlestonians northward in the early twentieth century. By 1930, both the city and the state of South Carolina had a white majority. Preservationists simultaneously turned the lower portions of the peninsula into white enclaves. Tradd Street, which one Charlestonian complained “was infested with negro dives of the lowest kind whose . . . orgies keep up all night,” earned Susan Pringle Frost’s ire in the late 1910s and 1920s. She oversaw the restoration of homes on the street and the concurrent removal of black tenants, who were forced to make way for white residents. “Today it is one of the most popular and attractive residential streets in the city,” Alston Deas, the first male president of the SPOD, proclaimed in 1928. The SPOD and other preservationists, in short, played a major role in instituting residential segregation in a city that had historically been integrated.38

Significantly, too, the SPOD insisted that its work was commensurate with a modern, thriving Charleston. Historic preservation not only protected the city’s priceless cultural heritage but also acted as a tourist draw (attracting money to defray the costs of preservation in the process) and fit with the commercial development of the city. “I want to emphasize that members of our society are not opposed to progress,” wrote Rosa M. Marks in a letter to the News and Courier. “We are most anxious to see industries and everything that would advance a city commercially come to Charleston and we will do every thing to help. But we want them properly located and not at the expense of the beauty and charm of Charleston’s distinctiveness.” After all, Marks argued, “this distinctiveness annually brings so many visitors to our city.” Mayor Stoney shared the preservationists’ vision. In 1929, he urged the city council to create the City Planning and Zoning Commission, and under his stewardship Charleston became the first city in the United States to pass a planning and zoning ordinance, which designated twenty-three downtown blocks as the “Old and Historic District.” The 1931 ordinance also created the Board of Architectural Review to approve architectural changes to structures in the protected district.39

With this act, the city acknowledged the economic value of its old buildings, effectively rejecting those who were skeptical about a future that was too indebted to the past. Although tensions between proponents of preservation and development persisted, the city threw its economic lot in with history. Commodifying Charleston’s past represented the most realistic route to economic progress. By 1929–30, the roughly 47,000 tourists who visited contributed $4 million to the local economy, making tourism the city’s largest industry. But Charleston had to be on guard. Two other cities took issue with its claim to be America’s Most Historic City and hoped to reap their just rewards from the title. Fredericksburg, Virginia, spoke out first, challenging the Charleston Chamber of Commerce to a debate on the issue. Williamsburg then joined the fray, and though it ridiculed the debate as a stunt “beneath [our] dignity,” it defended its superior antiquity. “If they want history,” one resident announced, “let them come to Williamsburg to get it.”40

* * * *

NOTWITHSTANDING THE CHALLENGES of its Virginia rivals, plenty of tourists went to Charleston for their history in the interwar period. The stories they heard had been carefully crafted by a group of local whites eager to showcase their city’s attractions and reaffirm their vision of the past. The women of the SPOD, for example, believed that the overzealous pursuit of modernity threatened both ancient buildings and white historical memory. If they lost the former, they also lost the latter—“an old order of culture,” in Susan Pringle Frost’s words. After the SPOD incorporated in 1928 and was reorganized under male leadership, the organization successfully lobbied the state legislature for tax exemptions for two of its houses and acquired federal funding for preservation efforts. By the late 1920s, the private spaces of the white elite were gradually becoming the sites of official public memory, supported by the weight of individual citizens and government institutions alike.41

The female members of the SPOD, for their part, hoped to defend a romantic memory of domesticity. As they ushered visitors through the homes they had rescued, these preservationists framed the dwellings as repositories of familial, and feminine, values, regaling tourists with legends of those who had lived there. They also stressed the colonial, revolutionary, and antebellum significance of the homes they guarded. SPOD members did little to connect them to secession, the Civil War, or slavery. Their work—and their particular brand of historical amnesia—played to the Colonial Revival craze of their day. Even locals with family histories that spoke more directly to the sectional crisis, such as Josephine Rhett Bacot, who was the daughter and granddaughter of antebellum fire-eaters Robert B. Rhett Jr. and Robert B. Rhett Sr., stressed that Charleston was “pre-eminently a Colonial city.”42

More generally, tourist narratives like the SPOD’s reflected the broader desire for sectional reconciliation ushered in by the Spanish-American War and World War I, as well as for a national culture constructed from a shared past. Although Confederate memory groups remained popular in the city, many early-twentieth-century Charlestonians acted as if they, too, were ready to let the war go. On the fiftieth anniversary of the firing on Fort Sumter in 1911, for instance, locals decided not to stage any public commemoration of the event. And tours to Fort Sumter, potentially the most divisive site to northern visitors, promoted reconciliation rather than recalling past antagonisms. Beginning in 1926, cruise boats left twice a day from a pier near the Fort Sumter Hotel, carrying thousands of tourists to the island fort every year by the end of the 1930s. Several small memorials on the grounds—one to Major Robert Anderson, another to Union defenders of the fort—illustrated the site’s symbolism of American, rather than Confederate, patriotism. The captain of the boat, a Syrian-born man named Shan Baitary who was a naturalized American citizen, drove home the point. According to one northern travel writer, Baitary finished his tour by “summing up the story of Sumter and expressing satisfaction that we are again a united people under one flag.”43

Interwar Charlestonians did not entirely elide what they viewed as the unique elements of life in the Lowcountry, nor did they ignore their southern heritage. The SPOD, like similar preservation organizations such as the Society for the Preservation of Spirituals and the short-lived Society for the Preservation of Manners and Customs of the South Carolina Low Country, sought to preserve the region’s traditions and culture. Charlestonians were also quick to capitalize on the city’s role in the sectional crisis and the Civil War after the publication of Gone with the Wind in 1936 and the release of the movie in 1939. In conjunction with the local premiere of the film, the Charleston Museum staged a “Gone with the Wind” exhibition, which ran throughout the winter tourist season. Featuring period dresses, jewelry, and other artifacts, the exhibition was a resounding hit, attracting 23,000 visitors.44

Still, the attention the SPOD paid to the city’s colonial past, as well as their disinterest in sectionally divisive elements, served to nationalize Charleston’s history, better enabling non-Charlestonians to consume and make their own. So, too, did the work of the Historical Commission of Charleston, created by the city council in 1933 to preserve and promote Charleston’s history. In 1935, for instance, the commission produced historical dramatizations for radio as a way to advertise Charleston’s lively history to listeners near and far. Most of the scripts testified to the commission’s deep interest in the city’s pirate, colonial, and Revolutionary War history.45

On Church Street, where a vibrant row of businesses catering to tourists sprang up during the 1920s, visitors could buy any number of guidebooks and pamphlets to help them learn of the city’s history and to determine which sites were worth seeking out. The list of must-sees included many of the same spots tourists had visited since the 1870s, though after 1931 their historical significance was officially affirmed since most of them lay within the protected historic district. A tour designed by the Historical Commission of Charleston took visitors from the Francis Marion Hotel, east along Calhoun past the old Citadel, and down Meeting Street toward the Old Powder Magazine and St. Philip’s and the Huguenot churches. After making their way toward to the Battery, they headed back up to Meeting and Broad, passing by various government buildings, and then to Church, Tradd, and Legare streets to view significant Charleston homes. Indicating the influences of the SPOD and other preservationists, visitors were much more likely than before to be pointed toward private residences—like the Heyward/Washington House, the Miles Brewton House, and the Rutledge, Rhett, Izard, Gibbes, and Elliott homes.46

As at the historic homes overseen by preservationists, the literature provided to tourists highlighted the national over the sectional, making little room for the Civil War. And even when the conflict warranted some mention, guidebook writers, like preservationists, ventured no further chronologically, giving the impression that the city’s history stopped in 1861. Picturesque Charleston, published in 1930, was typical. It celebrated the “varied characteristics of the city’s founder stock,” describing the English, Caribbean, French, and German origins of its early settlers, Charleston’s colorful brushes with piracy, its Revolutionary War skirmishes, and the fact that it was the location of “the first shot of the war between the States.” Fast-forwarding through nearly six decades during which apparently nothing of note transpired, Picturesque Charleston claimed that today the city was a paradise for “the student of the historic, the searcher after quiet, [and] the sportsman.”47

The authors of these guidebooks showed their debt to earlier Lost Cause thinkers when it came to slavery, a topic that was not divisive as long as it was presented in a flattering light. A few, like Picturesque Charleston, ignored the peculiar institution altogether. Other tourism guidebooks briefly mentioned slavery, if only to deny certain realities about it or defend it. In his 1939 Charleston: Azaleas and Old Bricks, Samuel Gaillard Stoney, an elite Charlestonian of Huguenot heritage who was an architect and preservationist, candidly acknowledged that slavery provided “the basis of most of the wealth” in the city. And yet despite its injustices, he insisted that slavery was “suited admirably . . . to the temperament of the Low-Country Negro.”48

Thomas Petigru Lesesne’s 1932 Landmarks of Charleston—which remained one of the most popular guides of the city two decades after it was first published—borrowed liberally from Cornelius Irvine Walker’s 1911 guidebook in challenging the common description of the Old Slave Mart. Echoing the influential Confederate memory maker, Lesesne questioned the slave-trading history of the Chalmers Street site, calling it the “Mythical Old Slave Market.” A descendant of two notable South Carolina families and a longtime News and Courier editor, Lesesne explained his objection at length: “Authorities are positive in saying that nowhere in Charleston was there a constituted slave market for the public auctioning of blacks from Africa.” Bemoaning that tourists were informed to the contrary, Lesesne also agreed with Walker in concluding that southern slaves “were in better care than were the peasantry in any other part of the world.”49

* * * *

THE ONE GUIDEBOOK from this period that stood out for the way it addressed slavery was produced, at least in part, by writers who were not native to Charleston. Researched and written by employees of the Federal Writers’ Project (FWP), a Works Progress Administration (WPA) program established in 1935, South Carolina: A Guide to the Palmetto State placed slavery at the center of the city’s and state’s history. Though largely bereft of sites related to the black past, the section on what to see in Charleston listed the Old Slave Mart as one of many places in the city where slaves had been sold. More generally, the guidebook identified slavery as the catalyst for the Civil War and recounted a history of slave insurrections, including Vesey’s failed plot, and white efforts to suppress them. A handful of Charlestonians—such as author Herbert Ravenel Sass, who was prone to romantic renderings of slavery in his own writing—served as consultants to the Columbia-based staff. But Louise Jones DuBose, the assistant director of the guide in Columbia and a sociologist by training, pushed her fellow southerners to be open-minded about what went into the guide. Even more influential was the FWP office in Washington, D.C., led by Negro Affairs editor Sterling Brown. A prominent black poet and English professor at Howard University, Brown and his staff closely monitored all state guidebook drafts to make sure that African Americans and their history and culture were neither ignored nor misrepresented.50

More remarkable than the WPA’s guide was the material assembled by black FWP writers as part of the South Carolina Negro Writers’ Project (SCNWP). In 1936, Henry Alsberg, the FWP national director, created the Office of Negro Affairs in order to ensure that African Americans would have a role in researching and writing the WPA state guidebooks. Following Alsberg’s instructions, Mabel Montgomery, South Carolina’s FWP director, enlisted ten black writers to collect information and draft essays about African American history and culture in South Carolina. These essays were to have been included in the state guide, as well as in a planned Negro Guide, though the latter volume was never published and only a fraction of the research made its way into South Carolina: A Guide to the Palmetto State. Still, the draft essays produced by the SCNWP writers, including Charlestonians Mildred Hare, Augustus Ladson, and Robert L. Nelson, outline an alternative approach to the past rooted as much, if not more, in black memory as in white.51

More than a dozen of the draft essays explored the history of slavery, emancipation, and Reconstruction. In researching these subjects, the SCNWP authors pushed far beyond traditional (white) source material. Augustus Ladson, for instance, interviewed several black Charlestonians, including Thomas E. Miller, for his history of the Vesey conspiracy. Meanwhile, the essay on slavery in South Carolina referred not only to Edward McCrady’s South Carolina Under Royal Government but also to the work of pioneering black historians Carter Woodson and W.E.B. Du Bois. Robert L. Nelson likewise balanced the perspective offered by Mary C. Simms Oliphant in her influential textbook The Simms History of South Carolina with the insights of Affie Singleton, an eighty-three-year-old former slave.52

Overall, the drafts were a far cry from what interwar visitors read when they came to Charleston. Armed with African American sources as well as testimony from ex-slaves and their descendants, the SCNWP writers crafted essays with a fresh and often critical perspective on South Carolina history. One essay, called “Negro Contributions to South Carolina,” underscored the horrors of the slave trade: “Slaves were bought and sold at the fairs in markets and at public auction. Family members would be divided, probably not to unite again in life. When love for parent by children and love of children by parent would be expressed in weeping, only whippings followed.” Other essays highlighted slaves’ quest for education or resistance to bondage. Despite being transported to a foreign land, separated from their family and friends, and distinguished by a skin color that made escape difficult, insisted one piece, “many slaves did run away, suicides were by no means uncommon, and every colony showed the fear of insurrections.”53

Three essays even offered detailed explications of slave plots and rebellions, including the 1739 Stono Insurrection and Vesey’s 1822 conspiracy. And the essay on the Stono uprising went so far as to justify slave rebellion in the name of liberty. “All humanity has the spirit of freedom planted deep within it, and will risk all in the barest hope of gaining it,” it began. Later, after highlighting the bloody outcome of the insurrection, the essay concluded that the extent “of the rebellion made it evident that there must have been some substantial cause for this feeling of hatred evinced by so many Negroes toward their masters. The Negro slaves were human, and only a spark was needed to set such tinder into flame.”54

* * * *

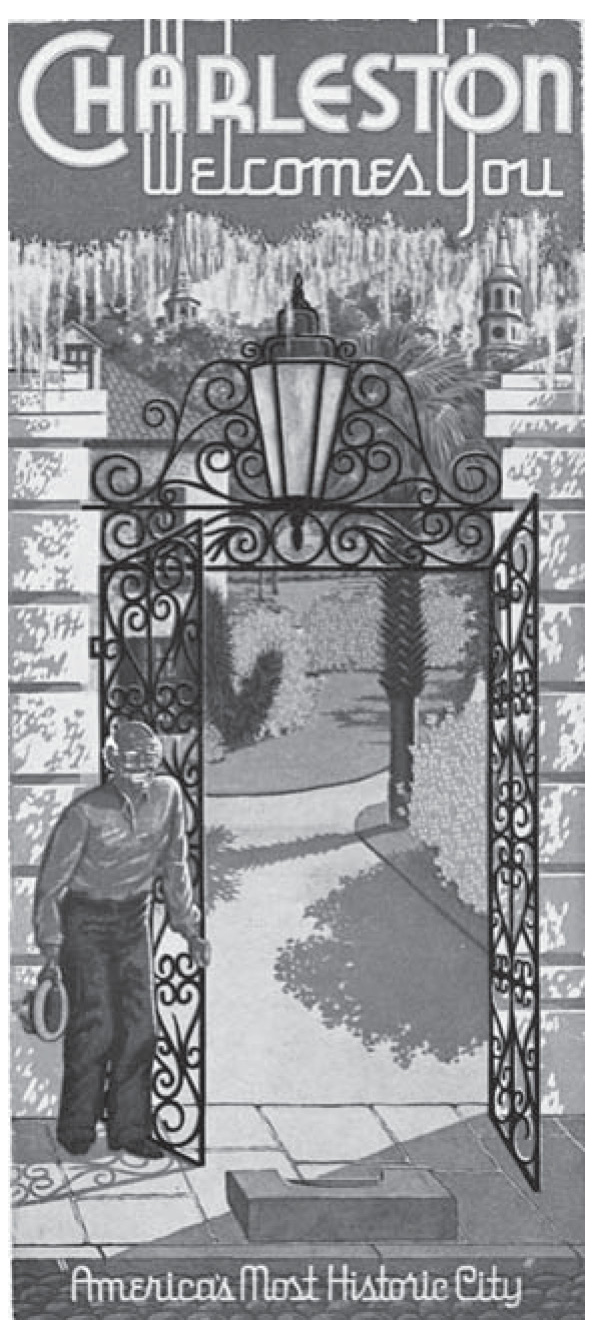

SINCE THE SOUTH Carolina Negro Writers’ Project essays remained unpublished, how visitors or tourism officials might have responded to the counternarrative they offered is unclear. It is certainly difficult to imagine a white Charlestonian admitting that rebellion was a reasonable response to enslavement. One simply did not say such things, even when prompted by tourists. Instead, most interwar Charleston boosters answered visitor interest in slavery by channeling it in a direction they preferred—by showcasing the loyal slave and his modern-day descendant. In her popular Street Strolls Around Charleston, South Carolina, Miriam Bellangee Wilson teased visitors with the possibility that they might see a mammy, or “mauma,” as they were called in the Lowcountry—“one of the fast disappearing type of loyal, true, and faithful house servants” with “snow white kinky hair.” A later edition of Wilson’s guidebook included a sketch of a black man in the guide, “an example,” read the caption, “of the fine old type [of] Negro[,] honest, intelligent, trustworthy.” Tourist pamphlets like “Charleston Welcomes You” also promised visitors that they would encounter a typical “darkey” during their stay. The cover of this brief guide featured a drawing of the city behind a wrought-iron fence. An elderly black man, hat in hand, stood opening the gate, a tourist’s very own loyal servant.55

This 1938 tourist brochure, “Charleston Welcomes You,” employed the faithful slave trope to advertise “America’s Most Historic City.”

Contemporary black Charlestonians also evoked the primitive and the exotic to out-of-town visitors. Sam Stoney informed readers of Charleston: Azaleas and Old Bricks that behind the city’s lavish mansions could be found “shanty communities that out-Africa Africa in some of their works and ways.” “Charleston Welcomes You” included a photograph of basket weavers and another of flower women, the latter group popularized by local artist Elizabeth O’Neill Verner. From her studio on Atlantic Street, Verner sold her drawings of the women to tourists eager to take home a piece of Charleston’s unique culture for themselves. She rendered flower women as features of the landscape, a charming aspect of nature, rather than as individuals. As she wrote in 1925, “one paints [the negro] as readily and fittingly into the landscape as a tree or marsh.”56

Verner’s interest in local blacks was not singular. In fact, she was a member of a small but significant group of white novelists, poets, painters, and singers who put Lowcountry African Americans and their culture at the center of their most significant creations. Headlined by DuBose Heyward, Julia Peterkin, and Josephine Pinckney, these artists sparked what today is known as the Charleston Renaissance. Although overshadowed by the Harlem Renaissance and the Fugitive and Agrarian movements in Nashville, this cultural movement produced important artistic organizations, such as the Poetry Society of South Carolina and the Charleston Etchers’ Club, and renowned novels such as Heyward’s best-selling Porgy and Peterkin’s Pulitzer Prize–winning Scarlet Sister Mary (1929). These novels, like many of the paintings, poems, and performances created during the Charleston Renaissance, focused squarely on the Lowcountry’s racial past and present, though in a manner that was less critical than the more probing works of southern contemporaries such as William Faulkner.57

That many Charleston Renaissance artists spent a good deal of time exploring black history and culture is not altogether surprising. After all, the 1920s were, in the words of Langston Hughes, “the period when the Negro was in vogue.” African American literature, sculpture, dancing, and especially music seemed both exotic and authentically American to white audiences drawn to jazz and the blues in the speakeasies of Harlem and Chicago. The Charleston Renaissance also reflected the rise of a regionalist artistic movement, which promoted regional folk culture of the American hinterland rather than the mass culture of Hollywood and Madison Avenue. For the artists and writers of the Charleston Renaissance, the ideals of the Old South in the Lowcountry could be resurrected, both to reestablish social order in modern society and to make money. And nothing distinguished the antebellum Lowcountry more than the slave culture that had developed on the plantations that surrounded Charleston.58

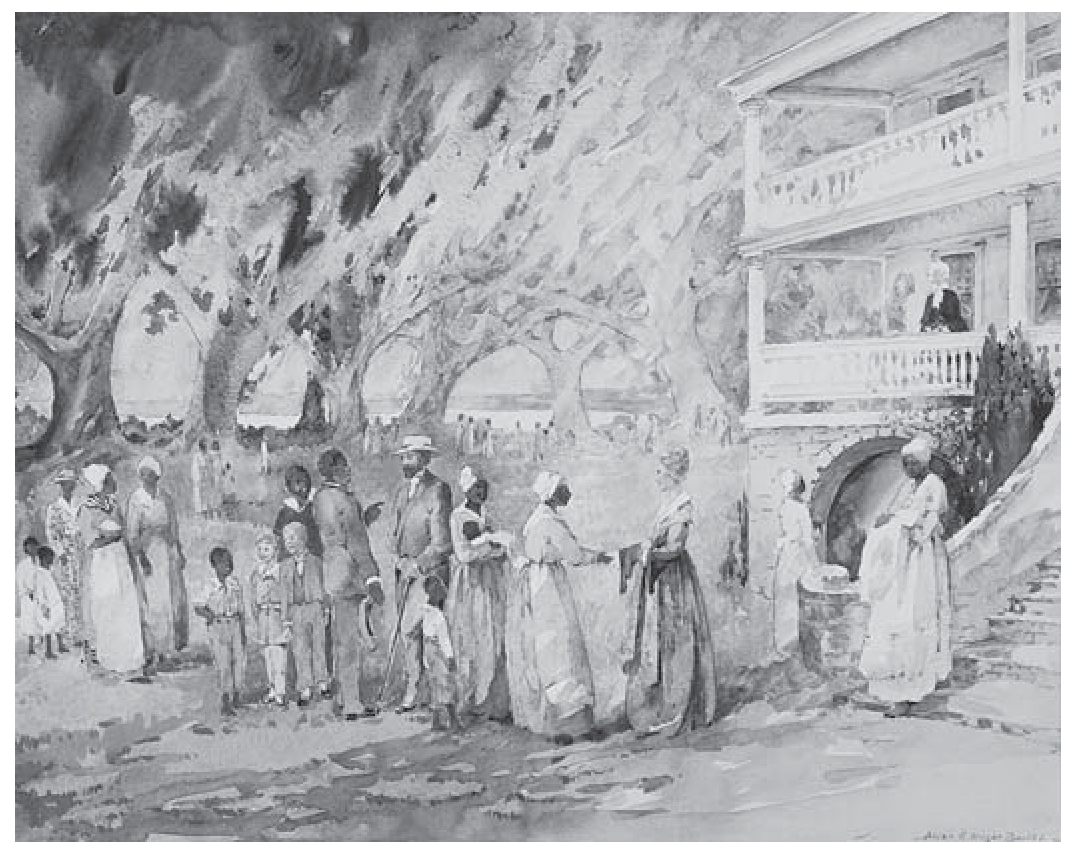

Alice Ravenel Huger Smith’s watercolor Sunday Morning at the Great House, ca. 1935, idealized life on an antebellum rice plantation.

Watercolorist Alice Ravenel Huger Smith, to take one example, created ethereal renderings of life on an antebellum rice plantation based on family memories. Born into a distinguished family in 1876, Smith learned to exalt Charleston’s past from her paternal grandmother, Eliza C.M. Huger Smith, and her father, Daniel Elliott Huger Smith, a Confederate veteran and amateur historian. In the mid-1920s, Smith brought these recollections to life with wistful watercolors of Lowcountry plantations and their surroundings. In 1936, she collected thirty of her impressionistic pieces in A Carolina Rice Plantation of the Fifties. The book, which also included a historical narrative written by her cousin, Herbert Ravenel Sass, and chapters from her father’s unpublished memoirs, sought to re-create and preserve a slice of plantation life in the 1850s for the generations that followed. “I threw the book back to the Golden Age before the Confederate War so as to give the right atmosphere because in my day times were hard,” Smith later explained.59

In contrast to the economic travails of Depression-era South Carolina, her watercolors, awash in the warm glow of her pastel pallet, evoke a genteel and affluent past in which both master and slave enjoyed life on the Carolina rice plantation. Art critics across the country took Smith’s rice paintings at face value, calling them “valuable historical documents.” So, too, did the tourists who frequented her studio, which was located on the opposite side of Atlantic Street from Elizabeth O’Neill Verner’s. Some came to buy art, while others sought out her shop to enjoy refreshments and to listen to Smith and her father (who made daily visits) spin stories about Charleston’s past that were every bit as dreamy as her watercolors.60

Charleston Renaissance author DuBose Heyward also looked back to a golden age in his best-selling novel Porgy, though his halcyon era was not the 1850s but rather the more recent past, “when men, not yet old, were boys in an ancient, beautiful city that time had forgotten before it destroyed.” Heyward came from old planter stock, but his father had died young, leaving his mother, Janie, to raise and support her family as one of several white Gullah impersonators in the city. Janie Heyward’s gift for storytelling, knowledge of Gullah, and enthusiasm for local history had a profound influence on DuBose’s literary career. He was also shaped by his job as a cotton checker on the docks of Charleston’s warehouse district, gaining an intimate look at the tenements, saloons, and bordellos that proliferated there.61

He drew on this exposure to working-class life in Porgy, which is set in Catfish Row in a dilapidated mansion turned black tenement. The tragic love story of a crippled beggar named Porgy and a drug-addicted prostitute named Bess, Heyward’s novel offers sympathetic, multidimensional portraits of its African American characters that contrast sharply with both the faceless slaves in Smith’s plantation watercolors and the racist caricatures found in the works of Joel Chandler Harris and Thomas Nelson Page. Yet like the works of Smith, Harris, and Page, Porgy played to predominant racial stereotypes. Heyward described blacks living in 1920s Charleston as “exotic as the Congo, and still able to abandon themselves utterly to the wild joy of fantastic play.” Evoking the paternalist ethos that Charleston’s blue bloods had long proclaimed, and on occasion lived up to, Heyward described Porgy’s world as the high tide of beggary: “His plea for help produced the simple reactions of a generous impulse, a movement of the hand, and the gift of a coin, instead of the elaborate and terrifying process of organized philanthropy.” And Porgy’s tragic conclusion—with the representative New Negro character, Sportin’ Life, driven out of Catfish Row, an intoxicated Bess lured to Savannah by stevedores, and Porgy left alone to mourn the loss of his loved one—suggests that the free future did not bode as well for Lowcountry blacks as had their enslaved past.62

Heyward echoed this point in a 1931 essay that touched on the Denmark Vesey conspiracy. One fact revealed by the trial record of the foiled 1822 insurrection, Heyward wrote, was that in southern courts of law enslaved people merited better treatment than their liberated descendants, albeit in deference to masters’ property rights rather than humanitarian considerations for the bondperson. He and his wife, Dorothy, an Ohio native who co-authored the stage adaptation of Porgy, were particularly taken with the Vesey conspiracy. Dorothy eventually wrote a play about the affair that was produced on Broadway in 1948. “The story of Denmark Vesey,” she explained, even “as told in the driest reference books, seems to have been dreamed up by a ‘true thriller’ writer after six martinis.” Though Dorothy found Vesey’s story intoxicating and displayed greater sympathy toward the “amazing” revolutionary than her fellow white Charlestonians, she placed the internal struggle of George Wilson, one of the slaves who betrayed the plot, at the center of her play. “George cannot sacrifice his master for the freedom of the Negro race,” explained a New York Times critic after watching the 1948 production. “His personal loyalties take precedence over his racial loyalties. This is the basic conflict of the play.” In the end, Dorothy counterbalanced the liberationist themes in her drama with the trope of the faithful slave.63

Although Dorothy Heyward’s Vesey play did not attract much of an audience, the wild success of her husband’s 1925 novel Porgy and the subsequent play and opera (the latter was called Porgy and Bess) was instrumental in placing the city and its black residents on the tourist itinerary. To many visitors clutching a copy of a guide like Miriam Bellangee Wilson’s Street Strolls, Cabbage Row—the inspiration for Heyward’s Catfish Row—was a site worth seeing. Its imagined inhabitants served as authentic primitives from an earlier age, though some guidebooks, like Wilson’s, also pointed out that Cabbage Row had recently been “reclaimed” by whites. By the mid-1930s, locals banked on the fact that Heyward’s works would bolster interest in Charleston and bring in deep-pocketed outsiders who would “give the gentry a chance to remove a lot of those ‘For Rent’ and ‘For Sale’ signs which grace most of the porticoed residences.”64

However much Porgy was the reason, big spenders did, in fact, come. Some stayed for months on end. Throughout the 1920s and 1930s, families with names like Guggenheim, Roosevelt, Vanderbilt, and du Pont acquired Lowcountry homes and plantations so that they could escape cold and drab northern cities during the winter. Elliman, Huyler, and Mullally, Inc., a real estate firm with an office on Church Street and one in New York City, facilitated these purchases for Yankees wanting their own little slice of Lowcountry romance.65

While northern snowbirds lent a hand in this preservationist campaign, they also put some southern traditions at risk. In a 1933 application to the Board of Architectural Review (BAR) for a permit to extend a fence at his Tradd Street home, for instance, C.W. Porter seems to have made reference to “slave quarters” behind the house. In response, architect Albert Simons, who was the most important voice on the BAR, wrote to the city engineer that “Lieutenant Porter might be interested to know that the servants’ quarters were never referred to as ‘slave quarters’ even in slavery times. The term ‘slave quarters’ is a recent invention of our winter colonists, the general use of which should be discouraged.”66

White Charlestonians not only taught northerners how to talk about their new properties, they also accommodated the tourist demand for encounters with traditional “darkeys” by incorporating them prominently into the Azalea Festival. Designed to draw thousands of visitors to the city during the lean years of the Depression, this celebration was first held in 1933. In addition to the usual parades, concerts, and pageants (both beauty and historical), for example, festival organizers arranged a street-crying contest for the city’s African American vegetable, seafood, and flower peddlers. One of the most popular attractions, a multiday exhibition of blacks husking rice, was staged at the Charleston Museum by Theodore D. Ravenel, who owned a rice plantation on the Combahee River. Each year, Ravenel brought in several African Americans to perform the husking process. In anticipation of the 1937 demonstrations, the News and Courier reported that the field hands “will be dressed in their field-working clothes and in all probability they will chant plantation songs as they go about their tasks.” They did sing during the shows, and because attendance was so high, the demonstration was extended for an additional week.67

This emphasis on the racial “other” typified urban tourism in the United States in the interwar years. Boosters in many American cities presented racial minorities as sights to take in rather than social problems, as many white middle-class travelers might have otherwise seen them. Their presence suggested an unchanging order that obscured contemporary divisions while at the same time making white visitors confident of their own status. San Francisco’s guidebook writers highlighted the Chinese presence. By the 1930s, as New Orleans began to cultivate a vibrant tourist industry to counter its Depression-era woes, so-called “darkeys” occupied much the same place in the tourist landscape as they did in Charleston. Dressing as mammies to sell pralines and playing the comical jester in Mardi Gras parades, they blended into the Crescent City scenery as charmingly as azaleas in full bloom.68

But even New Orleans—for all its sights and spectacles—could not hold a candle to Charleston when it came to the exploitation of its black residents and their culture. Renowned African explorer Mary L. Jobe Akeley hammered home this point when she attended the 1937 Azalea Festival. Listening to the chanting of Charleston’s rice huskers, Akeley told the News and Courier that she felt as if she were transported back to Africa. As the paper bragged, “She said she would shut her eyes and imagine herself back in the Congo, among savages more primitive than those she visited on her last trip.”69