“THIS IS ONE OF LONDON’S BEASTLIEST AFTERNOONS,” complained Philip Hewitt-Myring, an English journalist, in the winter of 1929. “It is bitterly cold outside,” he wrote, “and a clammy white fog is pressed hard against the windows and even forceing [sic] its way into the room through crevices that only a London fog could find.” On bleak days such as this one, Hewitt-Myring transported himself back in time and across the Atlantic to Charleston, where the year before he had spent three glorious spring weeks. Memories of the “quiet sun-drenched streets,” the “lovely old houses,” and “Magnolia Gardens . . . at the height of their beauty” cheered him, breaking through the impenetrable fog. What made these images all the more vivid and moving, he added, was that they were “set to music”—“the music of the rise and fall of the Spirituals which has haunted me ever since . . . I first heard it in Charleston.”1

Hewitt-Myring shared this reverie in a letter to the group that had taught him to appreciate the slave spirituals of Lowcountry South Carolina: the Society for the Preservation of Spirituals. For Hewitt-Myring, the singing troupe—which performed regularly in the 1920s and 1930s—was Charleston’s top attraction. As the Walter Hines Page Memorial Traveling Fellow in Journalism, Hewitt-Myring had chronicled his tourist experiences in Charleston for the News and Courier. Like English journalist Frank Dawson before him, Philip Hewitt-Myring was smitten with the city. Although 1920s Charleston bustled with tourists—unlike the sleepy city of Dawson’s day—it still retained plenty of its Old South charm. In fact, it was Charleston’s aged feel and its intimate connection to history that Hewitt-Myring found so alluring. The Society for the Preservation of Spirituals epitomized these qualities. In one of his final dispatches, he told his readers that he would be staying in Charleston for another week, mainly to attend the troupe’s upcoming spring concert, though he had already heard the group twice before. Betraying none of the reserve for which his countrymen were known, Hewitt-Myring declared that after each performance he “emerged . . . slightly drunk with the beauty of an entirely new and unforgettable experience.” It was impossible to write a series of articles about Charleston “without some reference to so piquant an ingredient in the city’s life,” he concluded, and so Hewitt-Myring dedicated an entire News and Courier column to the group.2

Remarkably, this piquant society—whose slave spirituals spiced up Charleston’s culture and intoxicated tourists like Hewitt-Myring—was entirely white. Although they sang music composed by the slaves who had toiled in South Carolina’s rice and cotton fields, members of the Society for the Preservation of Spirituals descended from the masters and mistresses who owned them. Born too late to have personally known life in the Old South, nearly all of them had been reared on nearby plantations by black maumas. Having left their homes for professional life in Charleston, they waxed romantic not only about the beautiful songs of former slaves but also about the loving bonds that they believed had characterized black and white relations on the antebellum plantation.3

The Society for the Preservation of Spirituals viewed performing spirituals and preserving them for posterity as its responsibility. In his lavish praise of the troupe, Hewitt-Myring never questioned this curious act of cultural stewardship. He even went so far as to claim that the white singers understood and performed slave spirituals better than blacks did anyway. The Englishman’s love affair with the Society for the Preservation of Spirituals, and with Charleston more generally, was especially passionate and eventually personal. By the end of his trip, the SPS had repaid his kindness, electing him an honorary member, and he went on to marry fellow journalist Eleanor Ball, daughter of William Watts Ball, editor of the Charleston News and Courier from 1927 to 1951.4

Yet Hewitt-Myring was not alone in his fervor for the city and its spirituals singers. Thousands of other travelers also discovered Charleston in the interwar years, helping to forge the quintessential tourist experience. During their stay in the historic city, visitors were entertained not just by the Society for the Preservation of Spirituals but also by three rival groups that emerged on its coattails: the Plantation Melody Singers, the Southern Home Spirituals, and the Plantation Echoes. Like the Society for the Preservation of Spirituals, the first two troupes consisted of elite whites. The Plantation Echoes, in contrast, was exclusively black, and a handful of members had once been enslaved themselves. Still, the message this black group conveyed through its performances, which were carefully staged by its white director, dovetailed with Charleston’s white spirituals troupes.

By the late 1920s, Charleston had become, quite simply, a place worthy “of musical pilgrimage,” in the words of Atlantic Monthly writer Mark Antony De Wolfe Howe. After a 1930 visit, Howe reported that the Great Depression had sapped the funds necessary for a restoration of the city’s physical monuments. So local preservationists had turned their attention to a different sort of commemorative campaign. To Howe’s mind, these singers had salvaged songs that seemed “to spring as inevitably from Charleston soil as the porticoed, seaward-looking houses that could be found nowhere else.”5

Along with several prominent whites who performed as Gullah raconteurs—regaling listeners with tales told in the dialect of Lowcountry slaves—these elites did more than entertain their audiences. They crafted a commemorative soundscape for Jim Crow Charleston.

* * * *

AT THE DAWN of the twentieth century, few locals would have predicted that the sounds of slavery would become all the rage in the interwar period. Indeed, not long after moving to Charleston in 1898, Ohio-born writer and fake slave badge critic John Bennett had tried in vain to find a publisher for a collection of 150 spirituals he had assembled with his new bride, Susan Smythe, and her sister. Reflecting on the popularity of the Society for the Preservation of Spirituals three decades later, Bennett told his children, “Mother and I were many years too soon. We started the interest here however; if that be any credit.”6

Members of the elite Charleston society into which Bennett had married were indifferent to the history and culture of freedpeople at the turn of the century. The young Yankee transplant, however, was mesmerized by Lowcountry blacks, past and present. Struggling to understand the Gullah dialect he heard on the streets of Charleston, he felt as if he “had entered a world of which he knew little or nothing . . . and to which he was [to be] forever a stranger and an alien.” Unlike so many of his new neighbors, he wanted to understand this world, an impetus in keeping with his relatively liberal racial politics.7

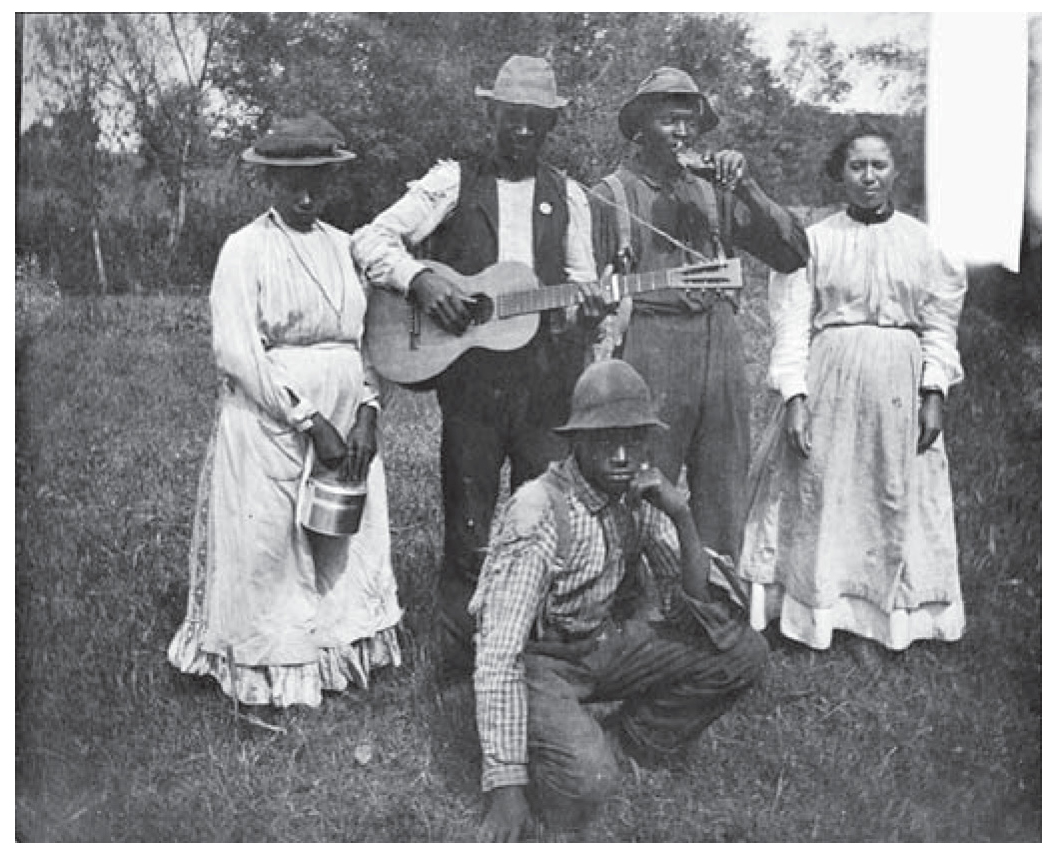

Fascinated with African American culture, Ohio-born John Bennett photographed these black workers at Woodburn Plantation, owned by his wife’s family, ca. 1905.

While on his 1902 honeymoon at the Smythes’ Woodburn Plantation in Pendleton, a summer resort for Charlestonians in the Upcountry, Bennett paid black children to sing spirituals for him. He began working with his wife and sister-in-law to transcribe the lyrics and sound out the music. He also mined his father-in-law’s library for works on African and southern history as well as a trunk of dusty documents from the Smythes’ Medway Plantation in nearby Berkeley County. Bennett augmented this course of study by making trips to the Charleston Library Society to learn about the African backgrounds of the people who had been transported to the city to be sold at auction. Recording his research in a series of scrapbooks that covered anything he could find on Gullah history, language, and culture, he taught himself to speak the dialect in the process.8

Charleston visitors regularly remarked on the distinctive sound of the slave-born tongue, which drew heavily on West African vocabulary and grammar. Like native whites, they tended to dismiss it as broken English. “The lowland negro of South Carolina has a barbaric dialect,” wrote New England journalist Edward King in 1875. “The English words seem to tumble all at once from his mouth, and to get sadly mixed whenever he endeavors to speak.” But Bennett, who published several pioneering studies of Gullah, concluded that it was much more than just flawed English. “It is the oddest negro patois in America; the most African; unaltered it is one of the oldest; if not the oldest, certainly it is the most archaic, and well worth the scientific and scholarly study which has been given the dialects of the Mississippi Delta, of Haiti, and of Martinique,” he wrote in the South Atlantic Quarterly in 1909.9

Bennett gave public lectures on Gullah music and folklore and, on occasion, performed spirituals while strumming along on a guitar. He tapped Gullah as a source for his fictional work as well. For his 1906 novel, The Treasure of Peyre Gaillard, Bennett combined family history, local legend, and his extensive research into Lowcountry slavery. When Booker T. Washington wanted to find out more about Sea Island spirituals, he wrote to Bennett for assistance. The Charleston author responded that he would send Washington a book for the Tuskegee Library.10

Though recognized as a Gullah expert in scholarly circles, Bennett never achieved popular acclaim. Society types deemed his work too salacious, as he never shied away from Gullah folktales that dealt with taboo subjects, such as miscegenation. Others dismissed it as too academic. But Bennett did inspire several successors who helped popularize Gullah history, songs, and storytelling. There was, for one, Bennett’s nephew by marriage, the architect and preservationist Sam Stoney, who had become interested in the language and culture as a young man listening to Bennett tell his dialect stories. By the late 1920s, Stoney’s proficiency in Gullah helped him get a job as dialogue coach for the northern actors cast in the stage version of DuBose Heyward’s novel Porgy. In the decades that followed, Stoney co-authored a collection of black creation tales, Black Genesis, and regularly spoke on and told stories in Gullah at events in Charleston and beyond. Like his uncle, Stoney developed a reputation for his insight into Gullah language and culture.11

Even more important was DuBose Heyward, whose novel, play, and opera thrust Gullah onto the national stage. A protégé of John Bennett, DuBose “spoke Gullah like a Gullah,” insisted his wife, Dorothy, and much of the dialogue of Porgy is rendered in the dialect. Indeed, DuBose joined Sam Stoney as a Gullah tutor for the actors in Porgy, which debuted in New York in the fall of 1927. He and Dorothy, with whom he adapted the novel for the stage, also included in the play a number of Gullah spirituals that had been collected by a group that DuBose had helped to found five years earlier: the Society for the Preservation of Spirituals.12

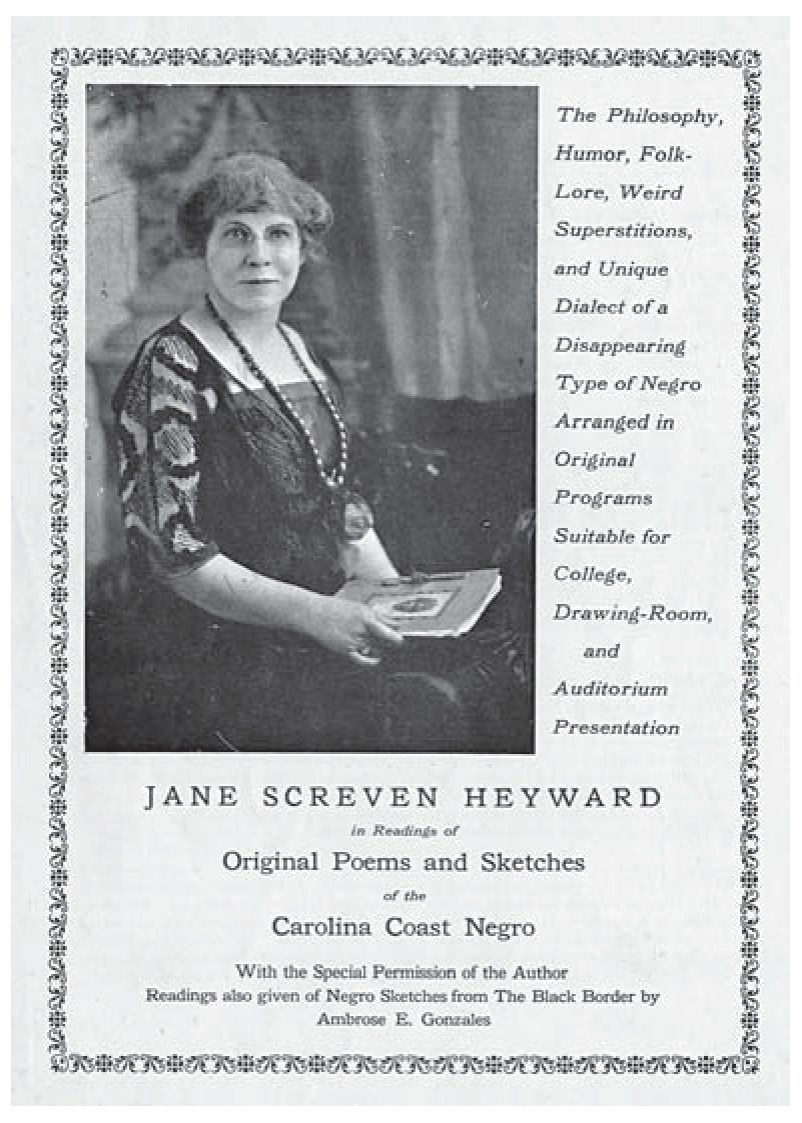

DuBose Heyward’s passion for Gullah music and folklore had been shaped not only by Bennett but also by his mother, Janie Screven DuBose Heyward, Charleston’s most influential Gullah impersonator. Despite her aristocratic pedigree (she descended from the DuBose family and married into the Heywards), Heyward took up professional writing when she was widowed as a young woman and forced to support her children. After publishing Songs of the Charleston Darkey in 1912, Janie Heyward began entertaining thousands of people from across the United States, sharing stories of slavery at the very moment that the city began to cultivate its special connection to history and to court tourists in earnest. By the early 1920s, she was Charleston’s go-to black raconteur.13

The idea that whites understood black culture and could thus perform blackness was hardly new. Blackface minstrels had enthralled white Americans since the early 1800s. By the turn of the century, white writers and raconteurs used black dialect and folktales to entertain audiences north and south, mimicking the slave on stage just as writers of the plantation school did on the page. Specializing in tales of slave mammies, women ranked as the most enthusiastic of these early-twentieth-century storytellers. More than simply entertainers, these slave impersonators cast themselves as serious interpreters of a bygone era. Performing in settings as varied as meetings of the United Daughters of the Confederacy and Chautauqua lectures, private parlors and hotel lobbies, they did important memory work in the service of the Lost Cause.14

Janie Heyward was among the most popular, her style and content more pleasing than John Bennett’s had ever been. Pundits regularly compared her to the leading lights of plantation-school literature. “What Nelson Page was to Virginia and Joel Chandler Harris was to Georgia in immortalizing this unique dialect and the relationship between master and slave . . . Mrs. Heyward was to South Carolina,” pronounced one observer. Like Harris and Page, Heyward’s dialect readings, which included her own stories and poems as well as folktales and jokes she collected from local blacks, placed the faithful slave front and center. It was a type she claimed to know from her upbringing on her family’s cotton plantations. As she announced in the introduction to one of her shows, “We of the Southland have as our heritage from our Slave holding ancestors, the understanding knowledge of the loving sympathy which existed in the old time between master and man.” Left to their own devices, she asserted, slaves had guarded their masters’ family and property during the Civil War. The “darkeys” to whom Heyward claimed to give voice thought little of emancipation, sometimes mocking it. Upon seeing a streetcar for the first time, she told her audiences, one Charleston black exclaimed, “My God! Deh Yankee too sma’at! Fus’ him is free deh Nigger, An’ now look! Him is free deh MULE.” In “What Mauma Thinks of Freedom,” such jocularity gave way to a plaintive nostalgia for slavery. Mauma proclaimed she had been “happy in de ole time,” missing the food, clothing, and shelter she had enjoyed under her generous master. Freedom afforded no such material comforts. Mauma concluded, “I wish Mass Lincoln happy mam/Wherebber he may be;/But I long foh deh ole, ole days/Befoh deh name ob ‘Free.’”15

Janie Screven DuBose Heyward, mother of Porgy author DuBose Heyward, entertained as a Gullah impersonator in the early twentieth century.

Through her dialect shows, Heyward hoped to “keep the spirit of mutual kindliness alive,” and at times she seemed optimistic that it might survive. But each of Heyward’s shows was also an act of preservation, an attempt to stop the march of time. The “old time darkey” she portrayed, Heyward observed at the beginning of one show, “has now passed from our civilization, going out with those conditions which produced it.” If she could not prevent his passing, at least she could offer stories, which came from her “heart and memory.” Audiences could then make them their own.16

According to white press accounts, this gift—Heyward’s ability to instill her memory of slavery into the hearts and minds of listeners—was invaluable. As a Savannah newspaper remarked after Heyward performed in the city in 1922, few people were privileged enough to have had their own maumas and thus have known slaves’ fidelity personally. But, this paper noted, Heyward transported audience members into the past, giving them a glimpse of what they had missed. This was an especially pressing issue for younger generations, who were born after emancipation had robbed them of their birthright. While Heyward’s readings were “wonderfully entertaining,” the News and Courier wrote, they were also “educational in their scope, and it is hoped that the school children will be able to enjoy hearing her in this recital as well as the grown folks.”17

The most notable aspect of Heyward’s performances was the skill with which she imitated the southern “darkey,” though skill was not the word her admirers used. “Mrs. Heyward impersonates her characters in an easy natural manner,” commented the Charleston Evening Post in 1924. The closeness she shared with her subjects represented the source of her purported authenticity, eliminating the need for acting. Like most of her fellow female performers, Heyward did not don the burnt cork mask that was the hallmark of the minstrel tradition or otherwise attempt to appear black. Despite—and perhaps to some extent because of—this lack of artifice, Heyward seemed to embody the southern “darkey” to white spectators. She performed with “a complete absence of affectation,” concluded one reporter.18

As word of Heyward’s readings spread, she was invited to perform by groups all over South Carolina, North Carolina, Virginia, Georgia, and Florida. In 1923, the Victor Talking Machine Company welcomed her to its Camden, New Jersey, studio to make records so that future generations might learn about the soon-to-be-extinct “darkey.” Non-Charlestonians were fascinated by the history she brought to life. In fact, Heyward owed much of her publishing success to an editor at Neale Publishing Company in New York, who had run across “What Mauma Thinks of Freedom” in a magazine in 1905.19

Many who congregated to hear her readings in Charleston were white tourists. Heyward regularly entertained visitors in the lobbies of the Francis Marion and Fort Sumter hotels. An announcement for one Fort Sumter Hotel performance entreated the public in general to attend, but sought to entice “particularly those who are sojourning in Charleston for a short time only.” “Visitors coming to Charleston for the first time,” it continued, “will be delighted by the ‘gullah’ stories told by Mrs. Heyward and with her perfect rendition of the dialect of the coast negroes.”20

Locals were confident, too, that Heyward’s shows would help northern audiences grasp an important truth. “Many years ago a distorted description of Southern slavery fanned the flames of great hate,” wrote an author from nearby Walterboro. Heyward’s performances, he held, provided a necessary corrective to this warped view of the Old South by recreating “an almost forgotten atmosphere of personal loyalty and feudal affection which once bound slave to master.”21

* * * *

THE MOST ACCLAIMED wardens of the whitewashed soundscape of slavery rose to prominence at the same time Janie Heyward was enjoying her popularity. Founded in the fall of 1922, the Society for the Preservation of Spirituals (SPS) included Heyward’s son DuBose and Sam Stoney, as well as scions of other prominent Lowcountry families, such as the Balls, Ravenels, Draytons, Porchers, Smythes, Pinckneys, Grimkés, and Hugers. Reared on plantations but now residing in Charleston, these homesick writers, lawyers, and bankers started meeting at each other’s homes to sing the Gullah spirituals they had loved as children. Initially little more than a private social club, the SPS quickly evolved into an organization that focused on performing and preserving spirituals for the broader public.22

Although the forty-seven founding members of the SPS had been born after the Civil War, most of them met the essential requirements of being the “descendants of plantation owners and slave owners” and “reared under the plantation traditions.” These membership restrictions—combined with a stipulation that the members could not be trained singers—made the SPS “perhaps the most unique society in existence,” ventured the Savannah Press after a 1926 performance. “You either lived on a plantation or you didn’t, and you can’t use political influence or money or good looks or any other handy asset to turn that trick for you.” This plantation pedigree, in turn, established the group’s authority on slave spirituals and its right to preserve them for future generations. Without even a hint of self-consciousness, these descendants of white slaveholders believed they were the appropriate guardians of this remnant of slave culture.23

From its beginnings, the group insisted that it was not a minstrel troupe. Modern scholarship on blackface minstrelsy emphasizes how the wildly popular art form afforded white performers and their often urban, working-class audiences a way to cross racial boundaries and safely explore fantasies about African American people and their culture. Yet like Janie Heyward, the SPS did not black up. Although the singers followed the blackface tradition of appropriating African American culture, they avoided the gaudy costumes and buffoonery that had characterized minstrelsy since the early nineteenth century. The SPS sang the songs of the enslaved but dressed like the masters and mistresses of the Old South. These elite Charleston men and women never let audiences forget where they stood in the city’s racial and social pecking order.24

Within two weeks of the society’s first show at a home on the Battery, however, there was concern that the troupe’s energetic performances “might be mistaken for a burlesque on the religious practice of the negroes, or the catch-penny mimicry of the familiar ‘black-face comedian,’” as SPS secretary Arthur J. Stoney stated at the group’s next meeting. Stoney recommended that to prevent any such misunderstanding, members do away with the ecstatic and rhythmic movements they had copied from blacks—the stomping and clapping that were essential accompaniments to Gullah spirituals—and simply sing. His suggestion did not go over well with his fellow spiritualists. “It was apparent from the glances directed at their Secretary,” Stoney reported in the minutes of the meeting, “that they reserved the right to shake, rattle and roll, when they got good and ready.” The society decided, instead, to begin each performance with an explanation that the intent was not to lampoon spirituals but rather to preserve them as relics of southern folklore.25

The SPS felt an obligation to do this important cultural work because, it believed, blacks themselves were not doing so. Fears over the future of slave spirituals had a long history. As early as 1868, an article in Lippincott’s Magazine of Literature observed that emancipation was resulting in “the rapid disuse of a class of songs long popular with negro slaves.” White abolitionists such as Thomas Wentworth Higginson, Charles Pickard Ware, and Lucy McKim Garrison tried to keep the tradition alive, publishing several collections of slave spirituals, including those sung in the Lowcountry. So, too, did black students—many of whom were former slaves—at Fisk University, in Nashville, Tennessee. In 1871, the Fisk Jubilee Singers embarked upon a multiyear tour throughout the North and Europe, performing spirituals to raise money for their financially distressed institution. They succeeded and, in the process, provided their white audiences with their first exposure to slave spirituals. One of the original Jubilee Singers was Benjamin M. Holmes, the Charleston-born slave who, as we saw in the prelude, had read the Emancipation Proclamation to his fellow prisoners in a pen in his hometown’s slave-trading district.26

Members of the all-white Society for the Preservation of Spirituals singing, clapping, and stomping in the Gullah style at a show, ca. 1955.

By the turn of the century, educational initiatives, transportation improvements, and demographic changes threatened the spirituals tradition, even on the isolated Sea Islands. As thousands of rural African Americans left for cities north and south (including Charleston) during the Great Migration, some lost touch with the music and culture of their ancestors. Meanwhile, rising literacy rates increased demand for printed hymnals in black churches, some of which preferred to deposit reminders of slavery—like spirituals—in the dustbin of history. “There would be no negro spirituals today,” concluded black tenor Ernest Johnson in 1929, “if it was not for the whites, who were responsible for their preservation, as the negro was desirous of forgetting everything associated with his slave days.”27

This was a gross overstatement. Spirituals remained important in the lives of many African Americans and a key part of the black singer’s repertoire well into the twentieth century. Reminiscing about growing up in Charleston in the 1920s and 1930s, College of Charleston professor Eugene C. Hunt noted the role that spirituals had played in his family. Hunt’s fellow Avery Normal Institute students also regularly performed spirituals in this period. Future civil rights leader Septima Poinsette Clark, who attended Avery from 1912 to 1916, recalled that the school choir sang spirituals for American Missionary Association trustees every time they visited the school, though at the time she, personally, disliked the songs because she did not appreciate their history. Avery students also raised money for the school by singing spirituals for white audiences.28

The SPS’s fear over the fate of black spirituals also reflected anxiety over the rumored passing of the old-time “darkey.” Both “the primitive negro” and his spirituals were fast dying out, one SPS admirer observed in 1930, ruined by “the canker of ‘civilization.’” But, according to this view, the country black untainted by excessive education had not yet entirely disappeared, which provided concerned whites an opportunity. Having grown up on area plantations, SPS members believed that they enjoyed an intimate familiarity with former slaves and their descendants, as well as with Gullah language and culture. “Often it was not until going off to college that the strong influence on their pronunciation of English was diminished,” insisted the son of an early SPS leader. The society’s Committee on Expeditions built upon these foundations by staying in regular contact with both white and black acquaintances in the surrounding countryside and setting up trips to plantations and churches where traditional black singing still occurred. Interracial tutorials, these trips took on the air of ethnographic expeditions, as SPS members ventured to remote locales to observe “natives” singing spirituals firsthand. After outings, a Committee on Research and Preservation documented each spiritual’s origin and history to create a record for future generations. The group took pride in the fact that the songs it performed were indigenous and exclusive to the Charleston area.29

The plantation excursions arranged by the SPS often occurred at night and, when possible, on evenings with a full moon. Certainly, there was a practical benefit to a full moon, since the light made it easier to see the assembled group perform. But a full moon also helped create the ambiance the preservationists hoped to find. Katherine C. Hutson, chair of the Committee on Research and Preservation, let readers of the News and Courier into this enchanted world in an article she published in 1929:

Imagine . . . yourself on a plantation in Coastal Carolina on a summer evening . . . and as you stand, wrapt in the witchery of the night, there steals from somewhere in the shadows a low wailing song. . . . The plaintive song increases in volume as new voices take up the melody and the tom-tom beats are gradually interspersed with the rhythmic staccato of hand clapping . . . and gradually, as one stirring from a dream, we realize that we have come upon a plantation praise house, the place where spirituals are born. Could any one fail to thrill at such a disclosure?30

Early on, the SPS attempted to re-create this thrill for its own pleasure and for small groups in private homes or at charitable functions around the city. By the mid-1920s, the society’s crowds and ambitions had expanded, and in the auditoriums where it performed, the SPS used elaborate stage scenery to evoke an antebellum plantation at nighttime. The group employed portable lights, some outfitted with blue bulbs that gave the impression of moonlight, and surrounded the singers with cuttings from azaleas, palms, and, of course, live oaks draped with Spanish moss. Male singers donned “tuxedos and broad, bow ties of the cavalier days and the women, Southern belles up to the southern tradition of beauty,” appeared in crinoline dresses. “One could shut one’s eyes and fancy the old plantation cabins, in dim light with dusky figures gathered in a circle, creating a native music out of Bible stories and prayers and a simple faith,” enthused the Savannah Morning News.31

The songs themselves began in a “slow, wailing manner,” with one singer giving the first line of each verse and the rest of the chorus then joining in. As the spirituals built to a crescendo, the group clapped, stomped, and cried out “spontaneous ejaculations toward the end of the measure, such as ‘Oh, Lord,’ or ‘Come own.’” SPS members gave themselves over to “an orgy of religion,” according to one observer. Crowds often joined in, seizing the opportunity to experiment with playing black themselves. “Before the concert was half over the audience was beating out the rhythms and was almost singing with them,” wrote the Savannah correspondent. “Another half hour and everyone would have been shouting.” Performances typically included over a dozen songs and consisted of two halves and an intermission, though audience members did not always leave their seats during the break. While the singers rested halfway through a 1924 show at Charleston High School, Janie Heyward took the stage to entertain with her Gullah readings.32

The letters that admirers wrote to the society make it clear that many fell under just the kind of spell Katherine C. Hutson hoped to achieve. “There is something about the singing of these old melodies by our own people,” one Charlestonian wrote to the SPS in 1931, “which always appeals to me and arouses in me a feeling of personal gratitude for the pleasure they give me.” Philip Hewitt-Myring, the group’s perennial fan and cheerleader, believed it was the performers’ unique love for, and knowledge of, the songs that combined to move even those who, like himself, had not been raised under plantation conditions. A Greenville lawyer marveled at the white troupe’s capacity to accurately reproduce black music. “The concert your society gave was different—nothing like it that I have heard—except the old-time darkey himself,” he wrote SPS president Harold “Dick” Reeves in 1928.33

Many doubted that African Americans themselves could do as well. According to the News and Courier, educational advances and “cultivated singing” hindered blacks’ own ability to perform spirituals in an authentic manner, even if they did still embrace the songs. Hewitt-Myring held that black spiritualists sang “not as darkies on a plantation but as paid performers on a stage.” The SPS, he contended, avoided this problem. The white troupe was so “absolutely faithful” in its concerts, insisted Matthew Page Andrews, a white historian from Baltimore, that it was more authentic than a black group could ever be. “It seemed to me,” noted Andrews after a 1927 show, “that the acting was perfection itself, because there was no semblance of acting, and no self-consciousness. In my opinion, the negroes themselves could not do it so well before an audience; they would feel they were on parade.” Like so many others, these white reviewers failed to see the irony in arguing that cultivated white singers could perform black spirituals authentically while cultivated black singers could not. So, too, did SPS members themselves.34

By preserving and performing Gullah spirituals, the SPS not only offered a tribute to the romance and grandeur of the world built by their slaveholding ancestors; they also embodied the ethos to which those forebears had aspired. Just as the Old South planter claimed to provide for the material and spiritual needs of his inferior and uncivilized black family, SPS members posited themselves as the protectors of a unique musical legacy of a people who seemed bound and determined to forget it. Eventually, the SPS expanded its purview. By 1927, when it created a Committee on Charity, the SPS determined that all of the profits it earned from performances should be used to relieve the “suffering and distress of the old time Negro.” From that point on, society members donated money to needy individuals as well as to organizations, such as the Charleston County Tuberculosis Association, which treated black patients, thus maintaining a paternalistic, but hardly inconsequential, charitable program for local African Americans.35

As its popularity increased, the group’s claims to a special connection with spirituals also grew. In 1931, the SPS published The Carolina Low-Country, a collection that included over four dozen spirituals, as well as nine essays on plantation music and culture. The society thereby staked its claim of ownership of the songs, though the decision to release a book had not been made lightly. Throughout the late 1920s, SPS members had wrestled with the possible consequences of publishing and recording Gullah spirituals. They worried that a permanent record of the songs, either oral or written, might subject the material to the damaging forces of commercialism and the corrupting voices of the uninitiated. This fear was one of the major reasons the group created an auxiliary junior spirituals society for members’ children in 1929, hoping to safeguard not simply the songs but also “the ‘word of mouth’ method of learning.” With The Carolina Low-Country, and the recording of spirituals in and around Charleston beginning in 1936, the SPS overcame these anxieties and sided with the necessity of preservation. It thereby established itself as the national authority on, and a leading repository of, Gullah spirituals.36

Many certainly saw the SPS as an assemblage of experts. The group regularly received letters from individuals seeking information on spirituals. Inspired by a feature story about the SPS in Etude magazine, for example, one Indiana woman asked for help with a presentation on spirituals she was slated to deliver to her women’s club. The successful 1927–28 Broadway run of the theatrical version of DuBose Heyward’s novel Porgy also elicited inquiries. As a founding member of the SPS, Heyward and his wife, Dorothy, with whom he had adapted the novel for the stage, made sure that the play’s program acknowledged the society “for furnishing words and music of spirituals incorporated” into Porgy. After the publication of The Carolina Low-Country a few years later, still more individuals—from academics to the Girl Scouts—wrote for permission to use songs in their own publications. Asking that proper acknowledgment be given to the group, the SPS always obliged.37

* * * *

FOR ALL OF their “sympathetic understanding” of the music they cherished, in the words of Alfred Huger, an early SPS president, society members completely failed to appreciate the meaning that slaves had attached to spirituals. Enslaved Americans composed four basic types of spirituals—freedom songs, alerting songs, protest songs, and slave auction songs—all of which spoke to the challenges and torment of bondage. Slave spirituals at their core were statements of “protest and resistance,” as black theologian Howard Thurman once argued. W.E.B. Du Bois called them songs of unhappiness, “of trouble and exile, of strife and hiding.” Former bondpeople stressed the way spirituals provided shelter from the storm of slavery. In the late 1930s, eighty-three-year-old Charlestonian Affie Singleton, who had been raised on an Ashley River plantation, said that “the masters and mistresses used to beat the slaves . . . so that at night they would resort to singing spirituals.” Another ex-bondperson recollected that “rough treatment . . . made them put greater expression into their songs.” Inspired by Old Testament stories of deliverance, slaves had drawn parallels between their own condition and those of Moses, Joshua, Daniel, and Noah. Escape from such oppression was a common theme. Frederick Douglass recalled that the Canaan about which he sang as a slave was not the heaven of his religion, but the North. The Lowcountry slave spirituals repertoire included many songs that captured this affinity between biblical deliverance and freedom from slavery, as the SPS’s The Carolina Low-Country attests.38

Yet the SPS interpreted spirituals differently. “The Society for the Preservation of Spirituals is anxious to correct the erroneous, yet general impression that the Spirituals were ‘slave music’ or the ‘music of bondage sung by a race in their oppression or degradation,’” wrote member Caroline Pinckney Rutledge. “The life of the plantation negro of our coastal section prior to the War Between the States, as attested by those few living today, was a happy one. They were well housed, well clothed and well fed, and were as free from care as irresponsible children.” In fact, the SPS insisted that the spiritual was an African rather than a slave song, and thus oppression accounted neither for its existence nor its meaning.39

A common error, Robert Gordon wrote in the essay he contributed to The Carolina Low-Country, was that the slave “created a large body of spirituals bewailing his position.” Gordon conceded that the idea of spiritual slavery—the oppression caused by sin and temptation—permeated the songs, and that the slave may have, at times, imbued them with multiple meanings. But, he concluded, the “total number of cases . . . in which we can be certain that he refers to physical and not to spiritual slavery can be counted on the fingers.” Other society members who wrote essays for the collection emphasized the slave’s comfort and good cheer—his access to plentiful rations and frequent banjo playing, for example—to prove that spirituals were devoid of any inherent critiques. DuBose Heyward offered the only essay in The Carolina Low-Country that departed from this bowdlerized vision of plantation life, dismissing the image of the faithful and contented slave as “the creation of a defensive South.” In the end, however, Heyward made it clear that he, too, believed that “it is likely that here in the Carolina Low-Country . . . the rural Negro experienced a higher state of physical and moral well being than at any other period in his history.”40

This, of course, was far from a novel vision of the Old South. But Charleston’s white spirituals singers invoked these images in a new way; they were living, breathing, and singing advertisements for the plantation legend. “I couldn’t help but think as I sat there that this was just as it was long ago,” New York conductor and composer Walter Damrosch commented after a 1935 SPS show. “The men in stocks and the pretty women in crinolines and hoop-skirts. It was very grand.” What’s more, the SPS made sure that its audiences did not miss its message about spirituals and the culture in which they were created. During a 1927 show in Columbia, SPS president Alfred Huger paused to explicate the meaning of the group’s songs throughout the program. He defined spirituals as “the reaction of the Christian religion upon primitive Negroes not long transplanted,” but he rejected the misconception that their tone and message bespoke “the hardships endured under slavery.” According to SPS executive secretary Katherine Hutson, “the minor mode and the longing and sadness expressed in the words” of spirituals, which included songs such as “Chillun Ob Duh Wilduhness Moan Fuh Bread” and “Gwine Res’ From All Muh Labuh,” did not reflect “the outcrying of an oppressed people.” Slave spirituals, she concluded, “were not originally or even generally the expression of the negroes longing for freedom.”41

To the SPS, Gullah spirituals were manifestations of religious belief—a fair reading of the songs, to be sure. In addition to being lamentations over slavery, spirituals were a product of Christian devotion, sung in the service of strengthening believers and bolstering their faith. Indeed, this was one of the reasons SPS members found the songs so appealing. Former SPS president Alfred Huger, for example, gained great comfort from spirituals in the waning years of his life, which he spent in Tryon, North Carolina, because of fragile health. After hearing the SPS on an NBC radio broadcast in 1936, Huger wrote the group a letter of thanks. He struggled to articulate how much joy the performance had brought him. Sensing that death was not far off, Huger was grateful for the songs and looked forward to the day when “the religious philosophy of our beautiful Negro Spirituals [will] be proven, in their original, unregimented form, to be the real and eternal spirit of Truth.”42

The solace he and his colleagues found in slave spirituals was an important part of their affection for the genre, and it should be not dismissed. Just because white spiritualists—and their white audiences, for that matter—did not endure slavery did not mean that their appreciation of the songs was insincere. A history of personal bondage was not a prerequisite for valuing the slave spiritual as an art form or as a vehicle of Christian devotion.

The problem was that, to the SPS, the songs were expressions of religious belief and little more. Local whites, for their part, never questioned the society’s interpretation of the spirituals it performed. In fact, influential voices—like News and Courier editor William Watts Ball—echoed the SPS’s take. In 1947, Ball published a column that took issue with renowned black singer Marian Anderson’s interpretation of spirituals as, in Ball’s words, “the dirge of a people in bondage, a melancholy music to be sung in sorrow.” Nothing could be further from the truth, he insisted. “As thoughtful Southerners know, the indigenous spiritual is anything but sad. It is a paean of joy, a song in praise of the Living God, a description of comforts of the Hereafter,” Ball concluded.43

A lack of sources makes black responses to the SPS more difficult to gauge, though a few things are certain. In Jim Crow South Carolina, whites could easily lay claim to what they insisted was a genuine memory of slavery with little fear of being challenged. Largely excluded from the public sphere, African Americans lacked the power to stop white singers from appropriating the sounds of slavery for themselves. Moreover, the SPS sang and stomped, above all, for the pleasure of whites. Few black Charlestonians, even those who might have been curious, ever saw an SPS show. In the midst of planning a free concert at the Academy of Music in 1931, for instance, the SPS discussed the possibility that some blacks might attend and wondered how they should be accommodated. The group determined to simply follow the Academy’s custom of placing African American patrons in a separate gallery, but it decided not to advertise the fact that blacks would be allowed at the show in the local papers. Instead, each SPS member was instructed “to inform his family servants to pass the word among their friends that they would be admitted.” The SPS spread the news of the free show, in other words, to those black Charlestonians least likely, or able, to take issue with its peculiar brand of cultural appropriation.44

SPS members, meanwhile, insisted that African Americans appreciated their work. In 1929, Alfred Huger claimed that “the colored people . . . have complimented the society” for its “able re-production” of Gullah spirituals, and one black schoolteacher in Spartanburg did go on record as a supporter of the society’s musical efforts. After attending a performance at a local theater, which she enjoyed “even in the far reaches of the balcony,” she wrote a letter to the Spartanburg Herald praising the group for taking spirituals seriously. Because many whites used the songs to mock blacks, she argued, the younger generation wanted to forget them. She thanked the society for its efforts to keep slave spirituals alive.45

White Charlestonians—and, by the mid-1920s, white tourists—found SPS concerts irresistible. Indeed, in addition to seeing the many historical sites in and around the city, visitors expected to catch an SPS show and were disappointed if they did not. In the spring of 1929, the editors of the News and Courier thanked the SPS for a recent performance, well attended by both Charlestonians and tourists. But, as the tourist season was just picking up, and more people would soon be in town, the paper hoped the society would arrange additional shows. The SPS owed that much to the city.46

The admiration of visitors such as Matthew Page Andrews, Philip Hewitt-Myring, and Walter Damrosch was amply reported by the press, but plenty of others responded similarly to the SPS. “A Yankee, who appreciates your work,” for example, wrote to the society and included a substantial donation. In thanking the northerner, one SPS member remarked that such generosity made him feel “that the war between the States was a mistake of the mind and not of the heart,” thus framing the gesture—and their mutual appreciation of slave spirituals—as proof of sectional reconciliation.47

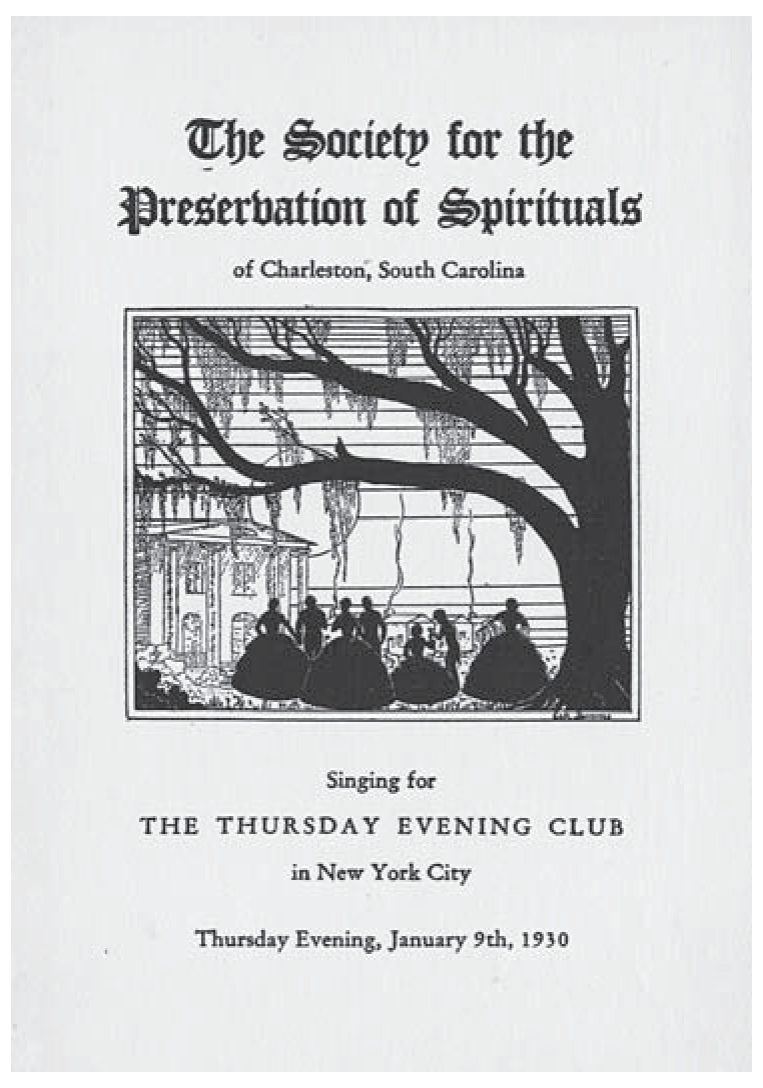

During its early years, the SPS performed primarily in Charleston and nearby towns in South Carolina and Georgia. By the late 1920s, appreciative Yankees had spread the word about the group up north. Invitations from northern dignitaries and musical organizations poured in. At the behest of the Massachusetts governor and the Boston mayor, the SPS traveled to Boston in 1929 to entertain the National Federation of Music Clubs at its annual conference. The singers gave three Boston-area concerts and then capped off the tour with a performance at the du Pont estate in Wilmington, Delaware, on its way home. The next year, Philadelphia welcomed the SPS, as did the exclusive Thursday Evening Club in New York City. In early 1935, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, First Lady Eleanor, and two hundred of their guests enjoyed an SPS performance in the East Room of the White House. Radio shows complemented these tours, providing a way for even more non-Charlestonians and non-southerners to hear the SPS sing. After its 1936 NBC broadcast, the society received letters of thanks from fans as far away as Pittsburgh and Chicago.48

Northerners who saw the group perform in person were especially effusive. In New York, the Thursday Evening Club was swept off its feet. The SPS was proud to learn from one audience member, Mrs. Woodrow Wilson, that another in the crowd, composer Walter Damrosch, could barely contain his enthusiasm. Delegates to the National Federation of Music Clubs meeting in Boston were impressed with the how the spiritualists sang “with the utter abandon of the negro.” In nearby Salem, this abandon affected even the most reserved of concertgoers. Three elderly women who sat through the first few songs “rather formally, bearing a dignified New England manner,” eventually became “infected with the contagion” of the music. All agreed that the SPS knew its craft well. A reporter for the Boston Transcript painted the picture for his readers: “Imagine, for example, the old song which Miss Jenkins and Mrs. Hutson learned from their mammy nurse, sung by a perfectly groomed vocale debutante!” The scene was at once a study in contrasts—here was the beautiful southern lady channeling the dark-skinned domestic slave—and a testament to the power of mimicry. It was also a testament to the lady’s key role in linking past and present, in perpetuating her memory of slavery.49

The Society for the Preservation of Spirituals performed up and down the East Coast in the interwar period.

Back home in Charleston, the value of these trips north was obvious to boosters eager to attract tourist dollars. If the slave-made mansions and gardens provided the foundation for creating Historic Charleston, it was the sounds of slavery—as interpreted by the descendants of Low-country slaveholders—that made it complete. The News and Courier published a laudatory editorial thanking the SPS for a marketing wind-fall that was hard to match. On the eve of the Boston trip, the Charleston Chamber of Commerce bombarded southern and northern newspapers with publicity stills of society members in their antebellum dress. The chamber had an Associated Press photographer tag along on the trip to New York and Philadelphia to capture and syndicate the society’s successes in real time. The SPS may even have attracted some buyers for surrounding plantations. Shortly after the prominent New York lawyer Victor Morawetz and his wife, Marjorie, sponsored the SPS concert at the Thursday Evening Club, they bought Fenwick Hall on Johns Island. Five years later, the socialites hosted the SPS for a private concert at their plantation.50

* * * *

NOT SURPRISINGLY, THE Society for the Preservation of Spirituals had competition in interwar Charleston. As we have seen, Avery Normal Institute students gave black spirituals recitals on a regular basis during these years. The Plantation Melody Singers and the Southern Home Spirituals—both founded in the mid-1920s by elite white women who ran in the same social circles as SPS members—did as well. Although significantly smaller than the SPS, these troupes took similar pride in their pedigrees.

The Plantation Melody Singers was formed by a dozen or so women who hoped “to reproduce the tender memories and deep affection” between masters and their slaves. Led by Lydia C. Ball, the group counted several other Balls, a few Ravenels, and a least one Legare and LaBruce as members. The Plantation Melody Singers began as an all-female group, but eventually it expanded to include several men. The Southern Home Spirituals was created by three former members of the Plantation Melody Singers—Maria Ravenel Gaillard, Mrs. William Seabrook, and Mrs. William Wayne—and seven other leading Charleston ladies. The Evening Post reported that “the singers, with one or two exceptions, were from the old plantations in this vicinity, and were thoroughly familiar with the old time negro prayer meeting spirituals.”51

Although the Plantation Melody Singers and Southern Home Spirituals boasted the same plantation lineage as the SPS, their appearance on stage was decidedly different. The Society for the Preservation of Spirituals may have sung, clapped, and stomped like slaves, but they dressed like southern cavaliers and belles. The Gullah impersonators making up the other two groups went much further in their racial masquerade; they tried not only to sing like slaves but also to look like them. Each member of the Plantation Melody Singers portrayed a black type, reported the Evening Post. There were “dignified old maumas, with snowy kerchief and turban and apron,” and “young girls with gay plaid ginghams and bright ornaments. . . . There were one or two of the less sober type of African . . . women who wore no head cloth over their unruly locks, no stiffly starched apron over their gaudy dresses. And there were gangling colored youths in pathetic garments of nondescript character.” In addition to this racial cross-dressing—a feature that was central to the minstrel tradition—both the Plantation Melody Singers and the Southern Home Spirituals members wore blackface.52

The content of Plantation Melody Singers and Southern Home Spirituals shows also had much more in common with minstrelsy than the SPS’s more restrained performances. Balancing their rendition of spirituals with storytelling and character skits, the Southern Home Spirituals treated their audiences to something closer to a variety show than a concert. The Plantation Melody Singers took things even further. Wrote the Evening Post of a 1927 performance in Kingstree, South Carolina, “The curtain went up upon a semicircle of Charleston folk, twelve in number, dressed in each small detail to represent the negro of yesterday.” At the time, most audiences would have associated this arrangement with minstrelsy, especially when they got a look at the singers’ garish costumes and heard their characters’ names: Jinnie, Nippy, Tildy Polite, Roxy, Galsy, Primus, Pigeon, Cumsee, and Old Uncle Noah. Finally, the routines performed by several of these characters evoked precisely the same response from their white audiences as did blackface minstrels. During a 1928 concert at Rock Hill, South Carolina, the young boy Primus “evoked peals of laughter with his assumed simplicity.”53

This was not the sort of reaction that the SPS intended to elicit from its audiences. In 1929, SPS president Alfred Huger told a Boston audience that “the society was in dead earnestness in its efforts to preserve and continue the singing of the spirituals and did not do it in a mood to make fun of colored people.” The SPS did, however, frequently share the stage with Gullah storyteller and SPS member Dick Reeves, whose readings tended to leave audiences in stitches.54

The Plantation Melody Singers and Southern Home Spirituals maintained busy schedules in the Charleston area throughout the late 1920s and early 1930s, and, like the SPS, they sang for both locals and tourists. Yet the Plantation Melody Singers and Southern Home Spirituals did not represent the SPS’s stiffest competition in interwar Charleston, as an intriguing episode suggests. On January 15, 1936, SPS executive secretary Katherine Hutson wrote to inform the steering committee of the popular Charleston Azalea Festival that members had recently voted to accept its invitation to perform one evening during the upcoming celebration. “This of course,” she continued, “is with the understanding that there will be no other group singing Spirituals in connection with the Azalea Festival.”55

The SPS was referring to the Plantation Echoes—a group that, by means of its all-black membership, represented a potent challenge to the SPS’s claim to authenticity. Since the advent of the Azalea Festival in 1934, the Plantation Echoes had enjoyed a prime-time evening slot in the entertainment lineup. Founded in 1933, the Echoes included fifty black field hands from Wadmalaw Island, several of whom were ex-slaves. The idea to create the group originated with Rosa Wilson, owner of Fairlawn Plantation, on which the singers lived. Alarmed by the plight of her tenants at the height of the Depression—several tied their crumbling shoes together with string—Wilson observed how they found solace in singing spirituals at their weekly religious meetings. She took comfort in knowing that “in these trying times there lived a people among us whose faith lifted them above material things” and determined to help the field hands find a way to earn money from their musical talents.56

Financing the endeavor with the sale of two pigs, Wilson arranged for the Plantation Echoes, as she dubbed the group, to debut a three-act show of singing and dancing at the Academy of Music on April 7, 1933. Their first public appearance attracted more than one thousand spectators. For the rest of the decade, the Echoes performed under the directorship of Wilson, offering multiple winter and spring concerts in Charleston and the surrounding area before mixed-race audiences. Eventually, the group was featured in national magazines, such as Etude and National Geographic, recorded by the Library of Congress, and invited on multiple occasions to participate in the National Folk Festival in Washington, D.C.57

Caesar Roper and Sam Simmons, former slaves and members of the Plantation Echoes, an all-black Gullah spirituals group. The Echoes undermined the Society for the Preservation of Spirituals’ claims to authenticity. From My Privilege, published by Rosa Wilson, 1934.

At times, SPS members actively promoted the Echoes’ work. DuBose Heyward arranged for a private Echoes performance for George Gershwin, who visited Charleston in 1933 to hear authentic black singing so he could compose the music for Porgy and Bess. “As far as I know nothing of this nature has been attempted before,” Heyward later said of the Echoes’ show. “There is an electrifying quality to the ‘shouting’ and the performers’ ability to shift from one time to another in perfect unison is a revelation.” Coming from an SPS co-founder, this was quite a compliment. But the prospect of performing alongside such an electric show appears to have been too much for Heyward’s fellow SPS members, especially when it was staged by a black group. Ultimately, the SPS removed itself from the 1936 Azalea Festival lineup.58

Not all of white Charleston shared the SPS’s fears about black rivals. Mayor Burnet Rhett Maybank was such a big fan of Heaven Bound—a morality play featuring spirituals that was staged by several black Charleston churches in the 1930s—that he requested it be performed every year during the spring tourist season. As the mayor who initiated the Azalea Festival in 1934, both he and the festival steering committee understood the significance of tourism to the municipal economy during the Depression, a time when the city came dangerously close to bankruptcy. When Congress repealed Prohibition in 1933 but South Carolina kept its no-alcohol law on the books, Maybank announced that tourists’ demands trumped state statutes: “We will give . . . liquor . . . to them whether it be legal or illegal.” Adopting a give-them-what-they-want approach, Maybank and the festival committee clamored to provide tourists with as many glimpses into black life as possible—whether it was through the lens of rice huskers, street criers, the Society for the Preservation of Spirituals, the Plantation Echoes, Heaven Bound, plantation field hands, or a sightseeing trip to area plantations led by preservationists. As a writer for Etude magazine observed in an article about the Plantation Echoes, Charleston had learned there was “a kind of gold mine” in showcasing the remnants of slave culture. If the SPS felt threatened by these black rivals, city boosters did not mind. The financial benefits outweighed any such concerns.59

And tourists did indeed go wild for the African American performers. As we have seen, the black rice huskers who sang spirituals at the 1937 Azalea Festival proved so popular that they extended their run at the Charleston Museum by a week. Rosa Wilson reported that tourists constituted the primary audience at Plantation Echoes shows in the 1930s and left wanting more. “Northerners,” she stated, “are very eager about this natural negro scene and even follow us to the plantation day after day.” Visitors from New York, Massachusetts, New Jersey, Connecticut, Ohio, Indiana, Georgia, and Northern Ireland took in a 1934 show. Heaven Bound also drew a large crowd of white tourists. According to one travel writer of the day, “it is one of those items on the ‘must’ list” during a trip to Charleston. Folklorist John A. Lomax, who recorded an Echoes show for the Library of Congress, complimented Rosa Wilson for her work in sharing the singers with the rest of the world, especially for letting “the negroes show they come direct from the farm through their style of dress” and their “natural” singing and clapping.60

Divining how the Plantation Echoes themselves felt about singing for their admiring audiences is not easy. Rosa Wilson noted that the Plantation Echoes had volunteered their services to a large historical pageant planned for the 1936 Azalea Festival. The director of the pageant, she further stated, “was very much pleased with how the plantation hands responded.” Yet Wilson’s stewardship of the Echoes must have made it difficult for members to register any discontent, and one tantalizing bit of evidence suggests that not everyone was a willing participant. At the Echoes’ 1938 spring concert at Hibernian Hall, a few of the field hands did not perform as they should have. “Several, notably the young bucks,” the News and Courier reported, “seemed to regard the presentation as a lark,” adding that the “more mature performers” sang well. These younger black men apparently did not take to playing the part of the old-time “darkey.” This sort of rebellion occurred elsewhere. According to spirituals expert and theologian Howard Thurman, one day in the early 1920s he and his fellow students at historically black Morehouse College sat stone-faced when the spirituals director called out the first line to a song. A contingent of white visitors was present, and they refused to sing spirituals “to delight and amuse white people.” The president of the college was humiliated.61

* * * *

IN 1934, A New York woman who had vacationed in Charleston since childhood and owned several homes in the city wrote an angry letter to the News and Courier. The first annual Azalea Festival had not, in her opinion, been a success. She complained primarily about the crowds that had descended upon Charleston for the festival, trampling hordes that ruined the city’s quaint feel and overwhelmed its streets. The commercialization of local charms, including black spiritualists, was also troublesome. It struck her as an “unsuitable dose of Hollywood.” “Beauty contests, hucksters’ contests, plantation echoes—a profaning of gentle reality for curious and unsympathetic eyes,” she wrote. “I am leaving it all, not to come back.”62

A profaning of gentle reality had been the hallmark of Charleston tourism for years, and along with infrastructure improvements, it had worked. Three hundred thousand tourists traveled to Charleston in 1939, double the number from just three years before and ten times the number who made the trip in the mid-1920s. The New Yorker’s consternation, in other words, was not widely shared, and probably reflected dismay that her city had been discovered by the masses as much as anything else.63

Those responsible for profaning their city never regretted playing to the desires of the curious traveler, but the spirituals societies, at least, may have been a victim of their own success. The Plantation Melody Singers noted as early as 1933 that ticket sales had declined. Attributing part of the drop to the Depression, Lydia C. Ball, the group’s president, also observed that radio stations routinely broadcast spirituals shows, and that the singing of spirituals now occurred well beyond Charleston, having almost become a national pastime. As she stated, “You often hear people say: ‘we do not have to go out to hear spirituals[,] we can get all we want at home.’” Ball resigned as Plantation Melody Singers president that year, and the group seems to have dissolved soon after. The Southern Home Spirituals lasted a bit longer, giving its last public concert in 1939. Appropriately, it was broadcast on the radio. The Plantation Echoes stopped performing in 1941.64

Even the Society for the Preservation of Spirituals entertained a proposal to disband at the end of the 1930s. The group’s biggest concern by this point was not sharing slave spirituals’ beauty and uplifting message; rather, it was ensuring that it had sufficient funds to pay for the cocktails members expected at meetings. In the end, the SPS decided to remain together, though the group staged fewer and fewer shows in the decades that followed.65

Nevertheless, white Charlestonians’ newfound passion for Gullah lived on. Sam Stoney continued to give lectures on and tell stories in the dialect. Fellow SPS member Dick Reeves, who had gained some local renown for reading from a collection of Gullah tales called The Black Border during SPS shows, performed both on stage and over the airwaves as a Gullah impersonator in the 1930s and 1940s. According to the account of one white listener, Reeves’s renditions of the Gullah tales were so convincing that a neighbor’s black servant who had been listening announced, “It’s just like a nigguh!” And while the Southern Home Spirituals stopped performing at the end of the 1930s, its founder and leader, Maria Ravenel Gaillard, did not. She continued to dress up as a slave and offer a program of Gullah readings and impersonations.66

What’s more, the sanitized memory of slavery promoted by Charleston’s spirituals troupes and performers remained alive and well, seeping through the crevices of the city’s tourism landscape like the fog of Philip Hewitt-Myring’s London. Local preservationists and tourism boosters increasingly made room for the Old South in Charleston’s historical narrative. Influenced by the wild popularity of Gone with the Wind, tourist brochures from the period evoked the antebellum grandeur of the region, featuring hoop-skirted southern belles on the cover. Several visitor guides even offered passing commentary on Gullah people and their culture. SPS member Herbert Ravenel Sass summed up these changes in a 1947 Saturday Evening Post article. “Charleston has become for thousands the visible affirmation of the most glamorous of all folk legends in America—the legend of the plantation civilization of the Old South,” he wrote. “A single morning spent wandering through its older streets, a single afternoon at one of the great plantations . . . prove that there was at least one region . . . where the Old South really was in many ways the handsome Old South of the legend.”67

Sass appropriately credited Charleston’s sights and spectacles for perpetuating this moonlight-and-magnolia vision of antebellum southern life. But white spirituals troupes and Gullah raconteurs—and, to a lesser extent, the black performers of the Plantation Echoes—provided the soundtrack for the tourist experience in Charleston. In the process, they repackaged the area’s Old South past into the comforting commodity that locals would peddle for decades to come.