We Don’t Go in for Slave Horrors

ON JULY 24, 1924, CHARLESTON REAL ESTATE BROKER Sidney S. Riggs wrote to historian Frederic Bancroft, who lived in Washington, D.C., about a new venture he had in mind. “We have recently completed two . . . modern hotels in this City,” Riggs informed Bancroft: the Fort Sumter, at the Battery, and the Francis Marion, across from Marion Square. “As we are able to take care of TOURISTS next season, I am thinking of putting the Old Slave Mart in such shape that visitors would be able to get some idea of how it looked in former days,” he explained. “I would welcome any suggestion from you as to this.”1

Bancroft was uniquely qualified to evaluate this unusual proposal. Since the late nineteenth century, the Columbia University–trained scholar had made regular pilgrimages to the South to conduct research for what he hoped would be the definitive study of the region before, during, and after the Civil War. Although Bancroft never completed his magnum opus, these southern tours—which included at least six visits to Charleston—provided ample grist for his pathbreaking Slave Trading in the Old South (1931).2

Bancroft and Riggs had been exchanging letters about the Old Slave Mart for several years. Riggs had a ten-year lease on the property, which was located in the heart of the city’s former slave-trading district. In the 1850s and early 1860s, Riggs’s father, John, had been a prominent Charleston slave broker, regularly selling enslaved men, women, and children at the slave-auction complex originally called Ryan’s Mart. A half century later, son Sidney had renovated a portion of that complex, which fronted Chalmers Street, transforming the Old Slave Mart, as it came to be known, from a two-story black tenement into a storage garage. Now, the Charleston realtor wondered whether he might turn a profit by restoring the building to the way it looked when men like his father had built fortunes buying and selling human chattel. Having spent a good deal of time over the past few decades inspecting what remained of Charleston’s slave-trading district, including the 6 Chalmers Street property, Bancroft liked Riggs’s plan a great deal. He admitted, however, that he had no sense of whether it was practical. “Personally,” Bancroft added, “I should like to see it done and should be glad to assist in any way in my power.”3

Notwithstanding Bancroft’s offer, Riggs never followed through with his plan. This is not surprising. By the mid-1920s, Charleston’s tourism boosters, preservationists, and entertainers were well on their way toward learning how to appease visitors’ desires to see sights and hear sounds associated with slavery and the Old South in a way that was palatable to local sensibilities. But topics such as the slave trade remained taboo.

* * * *

FEW THINGS TROUBLED white southerners more than the notion that their ancestors had actively engaged in the sale of men, women, and children and facilitated the destruction of families. So they tried to distance their region from human trafficking whenever possible. Sometimes this simply involved stating unequivocally that the practice had been foisted upon them by outsiders. In a critical 1885 review of a new edition of Uncle Tom’s Cabin, for instance, Frank Dawson’s News and Courier maintained that “the slaveholders at the North sold their slaves to the Southern people and then turned Abolitionists; that Northern ships owned by Northern men carried on the slave trade; and that Northern slave-dealing was carried on as late as seven or eight years before the outbreak of the Confederate war.” Almost a half century later, Society for the Preservation of Spirituals president Alfred Huger said much the same thing. “The South stands absolved of immediate responsibility for establishing the institution of slavery,” he wrote in his essay for the group’s 1931 book, The Carolina Low-Country. “Indisputable colonial records show that again and again the South protested against the traffic.”4

In other moments, white southerners traded stories intended to demonstrate that unlike their unscrupulous and hypocritical countrymen to the North, antebellum planters did everything they could to humanize the slave trade. In 1890, W.W. Legare, a Georgia professor with deep roots in Charleston, wrote the News and Courier about a telling event that he claimed had taken place decades earlier. At some point before the Civil War, a relative of antislavery senator Charles Sumner—later revealed to be the abolitionist’s brother, Albert—wanted to sell some enslaved people belonging to his wife’s estate in Charleston. Ignoring the pleas of a slave who preferred to be auctioned off together with the rest of his family, Albert instead sold just him to a trader. “As soon as the outrageous act of this satellite of the ‘higher law’ became known” in Charleston, Legare reported, “he was visited by a committee of gentlemen, who forced him to sell the negro at home, and then gave him twenty-four hours to leave the city.” Albert’s actions, claimed News and Courier editor James Hemphill, were “denounced by Southern people as monstrous.” This self-serving tale continued to circulate among elite Charlestonians for decades.5

White southerners also frequently scapegoated slave dealers as social pariahs who neither came from the Old South nor were accepted by its inhabitants. The lowly reputation of slave dealers reflected selective amnesia about the men who had devoted their lives to buying and selling human beings—a purposeful forgetting that is readily apparent in obituaries and biographies published in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. When Charleston slave trader Ziba B. Oakes died in 1871, for instance, his Charleston Courier obituary was front-page news. The newspaper reported that Oakes had made his money “in the Commission and Auction business,” but it failed to mention that much of that business had involved buying and selling people, or that Oakes had once owned Ryan’s Mart. The same was true of the obituaries of Oakes’s colleague John S. Riggs Jr. and a handful of other prominent slave dealers, including Alonzo J. White, John E. Bowers, T. Savage Heyward, and Louis D. DeSaussure. This pattern of deliberate omission extended beyond newspaper death notices. For instance, the Cyclopedia of Eminent and Representative Men of the Carolinas of the Nineteenth Century, a biographical compendium that Edward McCrady helped produce, scrubbed clean the records of two leading South Carolina slave dealers: Riggs and John Springs III.6

White Charlestonians’ selective amnesia about the slave trade often centered on the Old Slave Mart. As we have seen, visitor guidebooks raised doubts about the authenticity of the Chalmers Street site. In fact, Cornelius Irvine Walker’s take on the Old Slave Mart in his 1911 Guide to Charleston, S.C. proved remarkably influential, parroted not only by later guidebook writers but also by local newspapers, preservationists, and tourism officials. The News and Courier maintained in 1930 that the only thing certain about the Old Slave Mart “is that the establishment was never officially designated as an official general slave market, for no record of there ever having been such has ever been located.” The paper’s editor, William Watts Ball, found reassurance in the notion that Charleston did not have a city-sponsored slave market, explaining, “It does not appear that there existed sufficient buying and selling of slaves in the city to have warranted the establishment of any institution for the purpose.” Ten years later, Florence S. Milligan, a member of the Historical Commission of Charleston (HCC), objected to comments about the Old Slave Mart made by a Gray Line tour guide, whose accent suggested he was not a local. Milligan noted numerous factual errors in the guide’s presentation, including the claim that slaves had been sold at the Old Slave Mart, which had been reopened as a museum by Miriam B. Wilson just two years earlier. “Is it not wrong to assert that that Chalmers Street building was a slave market?” she wrote in her report. “I know it’s always done, but I’ve been told that it was never so used.”7

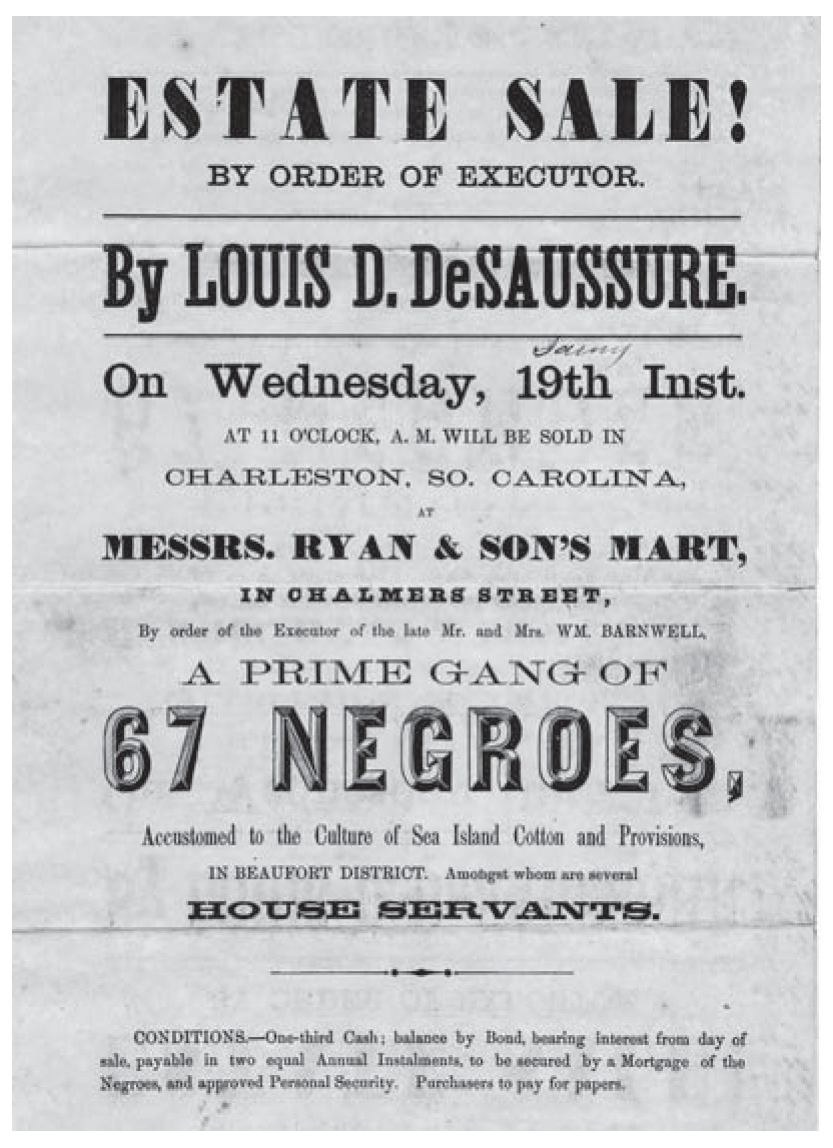

After the Civil War, white Charlestonians displayed historical amnesia about leading slave traders, such as Louis D. DeSaussure, and slave-auction sites, such as Ryan’s Mart.

Milligan’s colleague, HCC secretary Mary A. Sparkman, knew better. Notes that she compiled for the HCC in 1936 included nine typescript pages about Ryan’s Mart, Ryan’s Jail (the four-story brick barracoon that was part of the complex), and the slave trade more generally. Yet Sparkman, too, dissembled in describing the Old Slave Mart. Her 1952 tour guide training manual, which provided the foundation of the city’s official manual until the mid-1970s, made a point of stating that the Old Slave Mart had no official standing. “Our greatest historians and recognized authorities on recorded history are unanimously agreed that Charleston NEVER had a slave market,” Sparkman wrote. “New Orleans had one, but Charleston never did.” Like Walker, Sparkman and the Historical Commission did not want city guides to in any way suggest that Charleston sanctioned the slave trade by establishing a city-run market. Human trafficking had the imprimatur of New Orleans’s municipal government, Sparkman suggested, but visitors to Charleston needed to know that the trade had been strictly the business of private individuals there. Hence, she concluded, “Ryan’s Mart was merely another slave broker’s office, not the only one, in Charleston.” Ironically, then, in Sparkman’s attempt to prove that the slave trade had no official status in Charleston, the HCC secretary inadvertently demonstrated its ubiquity. Careful readers of Sparkman’s guide would understand that the buying and selling of human chattel was actually an everyday feature of commercial life in the city. Still, decades after Walker and his Lost Cause colleagues wrote slave-trading out of Charleston’s history—indeed, well into the 1970s—city boosters steadfastly perpetuated this whitewashed narrative.8

* * * *

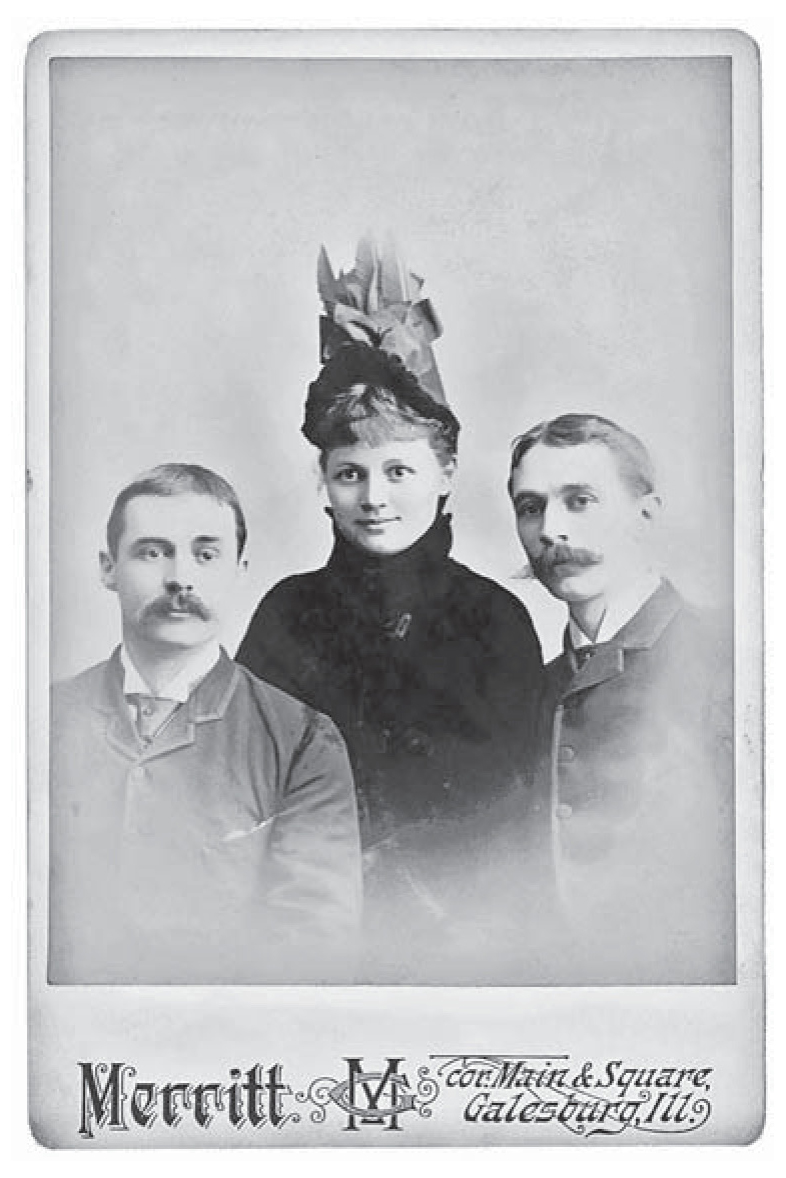

NO ONE IN early-twentieth-century America did more to ferret out information about the slave trade, or to expose white Charlestonians’ proclivity for forgetting about it, than Frederic Bancroft. Born in 1860 in Galesburg, Illinois, a town reputed to have been an Underground Railroad depot, Bancroft had learned to hate slavery as a child. While an undergraduate at Knox College, he gave public orations praising abolitionists John Brown and William Lloyd Garrison. His early interest in slavery contributed to his decision to focus on the American South as a graduate student at the Columbia School of Political Science, where he enrolled in 1882. Two decades later, Bancroft—whose wealthy older brother enabled him to enjoy the life of a gentleman scholar—set out to write a history of the South in the antebellum and Civil War eras.9

Historian Frederic Bancroft (left) visited Charleston many times to do research for his pathbreaking Slave Trading in the Old South (1931), which challenged white orthodoxy on the subject.

This project took Bancroft back to Charleston, a city he had first visited in 1887. What stands out most in Bancroft’s observations from this trip and several others he made to the city in the early 1900s is his fidelity to more than just written sources. Bancroft believed the only way to get a complete picture of the past was to combine the archival work of a historian with techniques more closely associated today with cultural anthropology and investigative journalism. He not only visited libraries and sought out plantation records; Bancroft also immersed himself in his surroundings, hoping to understand the region’s past from the perspective of its present residents. He wrote lengthy descriptions of the streets, buildings, and wharves he saw on his visits to Charleston, as well as of the behaviors and practices of its citizenry. And Bancroft struck up conversations with anyone he could—from Confederate veterans and white matrons to former bondpeople—teasing out information on a wide range of topics.10

Judging by the conversations he recorded in his southern trip diaries as well as his correspondence with Charlestonians, Bancroft had a knack for disguising his own beliefs on sensitive issues. During his 1902 visit, he regularly dined with Floride Cunningham, a pleasant and talkative white southerner whom Bancroft judged to be at least sixty years old. Despite his own antislavery convictions, he had little difficulty getting Cunningham to talk about slavery, her ancestors, and other topics related to the southern past. Cunningham, for instance, bragged that “her family always gave men Sat. after noon, & women did not go to the fields at all.” Five years later, Bancroft met with attorney Langdon Cheves, a descendant of two established Lowcountry families, at his home near the Ashley River. Although Cheves was more interested in discussing Reconstruction than earlier periods, Bancroft convinced the elite Charlestonian to share his family’s plantation books and answer questions about the Old South down to the most minor detail, including the turnover rate for overseers and the way that slaves’ shoe sizes were determined.11

Bancroft also had numerous conversations with Edward McCrady. The two historians spent most of their time talking about the American Revolution, secession, and the Civil War—all of which McCrady freely addressed. But when Bancroft raised the issue of human trafficking in Charleston, McCrady “seemed disagreeable & showed [a] nervous manner.” Despite McCrady’s discomfort, Bancroft pressed him for information about the various slave-dealing locales in the city, as well as the reputation of specific slave traders, such as partners Thomas Farr Capers and T. Savage Heyward. McCrady responded that he did not know their family backgrounds, though he insisted that they were auctioneers who sold sizable estates, which inevitably included enslaved laborers. As Bancroft later explained in Slave Trading in the Old South, this strategy of explaining away human trafficking as the incidental by-product of the larger social role that auctioneers performed—settling estates—had a long history. It was commonplace before the war and had become a sacrosanct tradition since then.12

Bancroft found a few white Charlestonians more forthcoming. A secessionist who claimed to have taken part in firing on Fort Sumter told him that thousands of enslaved people were sold out of Charleston and that members of the best families were professional traders. W. Mulbern, a wholesale grocer with a business on East Bay Street, informed Bancroft in 1902 that “aristocrats did not hesitate to deal slaves [and] make money on it.” When their conversation turned to the city’s slave trade, Mulbern added, “Better leave [it] out; it wouldn’t look well” to “our children.” Five years later, Bancroft returned to Charleston and spoke with T.W. Bacot, an attorney and brother-in-law of Edward McCrady. Unlike McCrady, Bacot displayed few misgivings about discussing human trafficking. He introduced Bancroft at the Charleston Library Society, helped him search for old slave advertisements, and advised him on how to determine the price of slaves auctioned off at equity court sales.13

Bancroft obtained even more information about the slave trade from his conversations with former slaves. In 1922, he bragged to a fellow historian about his “nearly 40 years’ experience” eliciting “historical evidence out of ex-slaves.” During an earlier trip to Charleston, Bancroft had recorded a lengthy conversation with William Washington and his wife, whom he met in a rubbish-filled yard a few doors down on Queen Street from Ryan’s Jail. Both freedpeople said that they had witnessed slave auctions in Charleston, and Mrs. Washington added that she had, in fact, been sold multiple times. “Were many children sold in this region?” Bancroft inquired. “Dey sell ’em like de hawk take de little chickens, dah,” replied Mrs. Washington, gesturing at some baby chickens in the yard. “Deh sen’ de chilluns out in de stree an’ yo’ nevah see’m agin. . . . De specahlatahs pick up de chilluns, like yo’ picu up dese chickens, till dey gits a drove & dey driv ’em in de public big road.” The Washingtons also described the punishment, including whippings with cowhide, switches, and straps, that the enslaved suffered at the hands of their masters.14

Stories such as these enthralled Bancroft so much that midway through his spring 1902 trip to the South he decided that he wanted to write a book focusing squarely on the domestic slave trade. He believed this volume would “wholly demolish the amiable traditions” that conveyed a false impression of southern slavery. Progressive-era historians tended to accept slaveholders’ paternalist claims at face value and characterize the institution as benevolent and civilizing. As a result, they de-emphasized the extent of the internal slave trade, argued that slave families were rarely broken up at auction, and underscored the lowly status of professional slave traders. Bancroft was especially critical of Ulrich B. Phillips, the Georgia-born professor whose portrait of slavery set the tone for southern historiography in the first half of the twentieth century. Indeed, after W.E.B. Du Bois wrote a scathing review of Phillips’s American Negro Slavery (1918), Bancroft sent him a letter of praise. Three days later, Bancroft told another historian that he would unleash “a most deadly array of facts” against the southern scholar in his forthcoming volume on the domestic slave trade.15

Bancroft continued to gather those facts in as discreet a fashion as possible over the next decade. In April 1922, not long after a trip to Charleston, he penned a note to the proprietor of the garage in the Old Slave Mart. “For historical purposes . . . I should like to know, in what year the negro tenements were removed from the old Slave Mart and when it was made into a garage.” Then, in deliberately vague fashion, he added, “I wish to make a note to a chapter that I have written about Charleston in the ’fifties.” This letter eventually found its way into the hands of Sidney S. Riggs, the son of slave broker John S. Riggs and Old Slave Mart leaseholder.16

Sidney Riggs proved to be a goldmine of information. He passed along details about the dimensions of, and changes made to, the Old Slave Mart as well as evidence relating to other sites associated with slavery. Riggs also put Bancroft in touch with individuals who had witnessed auctions at the Old Slave Mart. M.F. Kennedy, who as a young boy had attended several sales, confirmed that they took place from a long, three-foot-high black table, upon which the slave to be sold and auctioneer were perched. The crowd of prospective buyers stood to the west of the table, examining the human chattel put before them. Female slaves’ bodies were “partly exposed near the waist line as an exhibition no doubt of robustness,” the white Charlestonian told Bancroft.17

In his quest for information, Bancroft also struck up an extended correspondence with Theodore D. Jervey Jr., a wealthy lawyer, newspaper editor, and historian who had a unique take on slavery. Unlike many white Charlestonians, Jervey had his doubts about the peculiar institution. He was perfectly willing to admit that it conferred important benefits, functioning as an effective means of racial control, instructing slaves in important trades and skills, and cultivating close ties between master and bondman. Yet Jervey also believed that slavery had had a disastrous impact on the South because it contributed to the rapid increase in the number of African Americans there.18

Jervey’s unorthodox perspective on slavery helps explain Bancroft’s unusually forthright letters to the Charlestonian. In contrast to the way he approached most other southern whites, Bancroft did not disguise his desire to explore—and explode—the South’s cherished myths about the slave trade when writing Jervey. By the early 1920s, Bancroft had become particularly interested in documenting the life and reputation of Thomas N. Gadsden, the scion of an old Charleston family that included Colonel James Gadsden, the U.S. minister who negotiated the Gadsden Purchase. Bancroft had secured newspaper advertisements demonstrating that Thomas N. Gadsden was one of Charleston’s leading slave brokers from the 1830s through the 1850s, and he (correctly) suspected that Thomas was the brother of James Gadsden and two prominent ministers in Charleston. “To have a slave-trader in a family where there were several distinguished brothers, two of whom were clergymen, is rather shocking to the universally believed tradition that slave-traders were always hated,” he wrote Jervey in 1920.19

Bancroft included a detailed portrait of Thomas N. Gadsden in his seminal 1931 study Slave Trading in the Old South, which featured an entire chapter on human trafficking in Charleston. This work broke new ground on a variety of fronts. A sharp departure from the scholarly consensus on the domestic slave trade, it was among the first histories to incorporate slave testimony. For decades, Slave Trading in the Old South stood as the definitive study of the domestic slave trade, anticipating arguments about the commercial and exploitive nature of southern slavery that are widely accepted by historians today.20

Amazingly, Jervey managed to convince his fellow members of the Charleston Library Society Book Committee to purchase a copy of Bancroft’s book. We do not know precisely what the Charlestonian thought of Bancroft’s history, though a note Jervey wrote about the promotional circular for the book provides a clue. “After gazing at the illustration which accompanied your circular,” he wrote Bancroft, “I realize that it would be impossible for scholarship to present a more hideous picture of the ‘Old South.’” Referring to Eyre Crowe’s depiction of a slave auction near the Old Exchange Building (see the second image in the prelude), which was reproduced in Slave Trading in the Old South, Jervey was repelled by “the ferocious Southern types,” yearning to buy one of the African Americans up for sale. “There will be much to learn” in your book, he told Bancroft.21

No doubt there was, though not everyone in Charleston welcomed its lessons. William Watts Ball, the editor of the News and Courier, penned a lengthy and overwhelmingly negative review of Slave Trading in the Old South. A conservative from a wealthy Upcountry family, Ball had little patience for Bancroft’s thinly veiled moral outrage. Indeed, he subscribed to the notion that as practiced in the Old South slavery was more humane than anywhere else, noting the longevity of the enslaved there when compared to other regions with slavery. White southerners knew the real history of slavery in the South, Ball insisted, regardless of what primary evidence or statistics might suggest to a northern scholar. And if the stories passed over dinner tables were not enough to reassure his readers, Ball offered up the work of Ulrich B. Phillips, whose “great book” on American slavery “has been so fully, adequately and justly written . . . that nothing substantially modifying the final verdict is likely to be produced by another man.”22

Ball’s review infuriated Bancroft. He had no problem with criticism; in fact, Bancroft claimed to welcome it, if only to give him an excuse to write a preface to a second edition. Ball’s News and Courier review, however, was no such refutation. The Charleston editor “denied not one of my assertions, but changed the subject to slavery, and proceeded accordingly,” Bancroft told Jervey. Ball lauded Phillips’s American Negro Slavery, “but neither he nor anyone else has undertaken to answer my criticisms and ridicule of Phillips.”23

* * * *

FREDERIC BANCROFT WAS not alone in his quest to preserve the memories of former slaves. As we saw in chapter 5, black schools, churches, clubs, and families kept alive a countermemory in the segregated spaces of Jim Crow Charleston. Local whites occasionally lent a hand, too. In the 1920s, Leonarda J. Aimar compiled a book of stories told by ex-slaves who worked for her family. She also recorded the reminiscences of William Pinckney, a former bondman who spoke with remarkable openness about the discipline and sale of slaves in the city. Intimately familiar with the Work House, Pinckney told Aimar that individuals sent to the “sugar house” could be beaten, whipped, placed in the stocks, or forced to walk the treadmill.24

Such candor, however, was rare in the segregated South, at least in racially mixed company. Faced with the strictures of Jim Crow culture, ex-slaves often put a positive spin on life before the Civil War when they spoke with white southerners for fear that talking honestly might bring significant social or economic repercussions. As Martin Jackson, a former bondman from Texas interviewed as part of the Federal Writers’ Project (FWP), put the matter: “Lots of old slaves closes the door before they tell the truth about their days of slavery. When the door is open, they tell how kind their masters was and how rosy it all was.”25

This candor problem has been highlighted by scholars as one of the chief challenges in using the thousands of FWP interviews to reconstruct life in the Old South, and for good reason. But when the interviews are approached as artifacts of historical memory—as reflections not simply of what happened in the past but of how historical memories are shaped over the course of time and by the demands of the present—the candor problem no longer appears so problematic. On the contrary, when examined alongside documents produced by regional, state, and national offices, FWP interviews underscore the high stakes and contested nature of the memory of slavery more than seventy years after its abolition.26

A Works Progress Administration (WPA) program created in 1935, the FWP launched its ambitious campaign to interview former slaves in more than a dozen southern and border states in the spring of 1937. The initial goal of the FWP had been to hire unemployed writers to assemble and author a single, multivolume guidebook for the United States. (The FWP eventually settled on producing a series of state and local guidebooks—like the South Carolina guide discussed in chapter 6—rather than a single national guide.) When the mostly black writers hired to make sure that African American history and culture were included in WPA guidebooks began fanning out across the South in 1936, a handful of them took it upon themselves to record the memories of ex-slaves. Early the following year, the Florida Writers’ Project forwarded some of these stories to the national headquarters in Washington, D.C., where they captured the imagination of FWP folklore editor John A. Lomax. A Texas folklorist with a passion for black material, Lomax would record the Plantation Echoes for the Library of Congress later that year. He immediately recognized the value of these ex-slave interviews, too. So did Negro Affairs editor Sterling A. Brown and associate director George Cronyn.27

In the first week of April 1937, Cronyn instructed southern FWP offices to begin the process of identifying and interviewing former bondpeople. He then distributed a questionnaire that John Lomax had designed for interviewers. These questions, which functioned as an interview script for FWP employees, were far from perfect. Some were leading, others presumptuous. As a whole, however, the questionnaire touched on a range of salient and provocative topics—from slaves’ quarters, clothing, work, and religious beliefs to the sale, discipline, and resistance of the enslaved. As Lomax explained in the questionnaire’s preface, “The main purpose of these detailed and homely questions is to get the Negro interested in talking about the days of slavery. If he will talk freely, he should be encouraged to say what he pleases without reference to the questions.”28

Even a cursory examination of the FWP interviews in the Charleston area, however, indicates that many of the ex-slaves who spoke with white writers did not talk freely; instead, they told their interviewers what they thought they would want to hear. According to an account written by interviewer Jessie A. Butler, Abbey Mishow, a former bondwoman from Georgetown County who had lost her mother at a young age, characterized her owners as loving, substitute parents. “As she mentioned the name of the old ‘missus,’ and enumerated the names of her erstwhile owners,” the white writer reported, “Abbey’s old, wrinkled, black face softened with memories and her voice became gentle as she told of the care and kindness she had received.” Amos Gadsden, who had lived with his owners on St. Philip Street in Charleston, also emphasized his kindly mistress in his conversation with Martha S. Pinckney. “I never got a slap from my mistress; I was treated like a white person,” he explained.29

These responses not only reflected former slaves’ understanding of racial etiquette in the Jim Crow South; they also bespoke the economic realities of elderly African Americans living at the tail end of the Great Depression. After eighty-year-old John Hamilton answered white writer Gyland H. Hamlin’s question in expected fashion—“Yassuh, ole Maussa treat us good”—he explained that he depended “on de w’ite folks” for help. “You gimme a nickel or dime?” asked Hamilton at the end of the conversation, having held up his part of the implicit bargain. “T’ank you, suh. T’ank you kin’ly,” he responded, once Hamlin followed through on his end.30

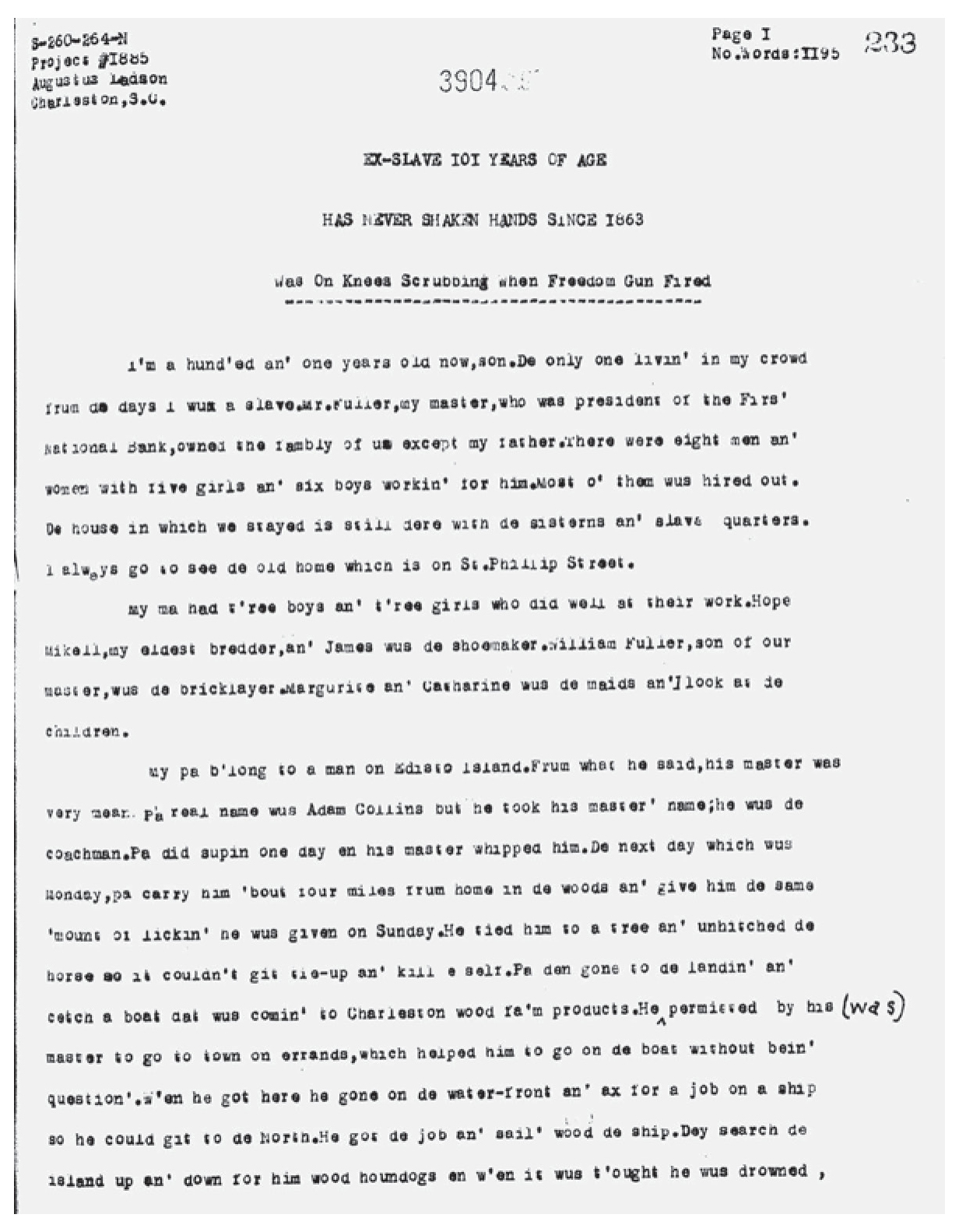

The slaves who spoke to Augustus Ladson—the only black FWP employee who interviewed a significant number of bondpeople in Charleston—painted a much different picture. Prince Smith, an ex-slave from Wadmalaw Island, informed Ladson that many of the slaves who worked on nearby plantations were forced to labor in the cotton fields seven days a week and were subjected to severe lashings if they failed to finish their work quota. Even Smith’s owner, whom he judged a gentleman who treated his slaves well, employed a system of punishment that today would meet any reasonable definition of torture. Elijah Green, the former slave who said he had dug the grave of John C. Calhoun in his youth, relayed an equally unvarnished portrait of slavery to Ladson. A lifelong resident of Charleston, Green was a well-known figure in the interwar period. When Green spoke with Ladson, he echoed William Pinckney’s comments about the Work House and the punishment of slaves. Being caught with a pencil and paper was treated as a major offense—“you might as well had kill your master or missus.” The elderly ex-slave also described Thomas Ryan, the former proprietor of the Old Slave Mart, as cruel. “He’d lick his slaves to death,” claimed Green.31

Such bleak portraits of antebellum slavery were unsettling to many of the FWP directors in the South. The national office had clearly stipulated at the outset of the project that writers “should not censor any material collected, regardless of its nature.” This directive, however, was not always followed. Scholars have unearthed evidence that interviews recorded in at least four states—Mississippi, Texas, Georgia, and Virginia—were revised at either the state or national level, often softening their portrait of slavery as a result. Officials in South Carolina did not go this far, but correspondence between the state FWP office in Columbia and the district office in Charleston reveals that white employees sought to discourage the collection of interviews that were overly critical of slavery in favor of those that offered a more positive take.32

Just one month into the program, Charleston district director Chalmers Murray wrote to South Carolina director Mabel Montgomery about two stories recorded in Beaufort by Chlotilde R. Martin. Murray had decided not to forward the accounts because they contained “apparent falsehoods” that “are utterly unfair to the pre-war south.” Murray informed his superior that “we have discussed this subject several times in the office, and it is the unanimous opinion of the Charleston staff that stories of this kind are of little value.” An Edisto Island–born journalist, Murray had a deep interest in Gullah lore and culture, which was reflected in many of his publications, including his novel Here Come Joe Mungin. Yet Murray did not think that former slaves who had survived into the 1930s were reliable sources about life in the Old South since most of them had been just children before the war, and “negroes are greatly given to fabrication.” Thus, Murray concluded that “the ex-slaves are not telling their own experiences in many instances—they are merely repeating what some one else told them about slavery times.” One can easily spot “the propaganda behind most of their statements,” he asserted.33

Murray detailed this so-called propaganda in a letter he sent to Martin, the interviewer. “It is apparent in reading your recent stories that the narrators have little if any regard for the truth, and do their best to paint slavery days in the darkest colors,” he told Martin, who, like Murray, was a white, college-educated journalist. Although Murray cautioned against censorship, he did “not think it wise to take down just any statement an ex-slave might make regarding a controversial subject like slavery.” Complaining that Martin’s interviewees “have evidently no sense of moral values,” Murray observed that their claims that the enslaved were issued starvation rations and inadequate clothing flatly contradicted evidence that had been culled from plantation records. “Spend some time in finding out about the reputation of the persons you propose to interview,” he advised. “When you actually interview the person, use all powers at your command to glean the truth from him.” It is not clear whether Martin heeded Murray’s suggestions, and there is no record that she interviewed another subject. Regardless, Murray eventually forwarded the two narratives he had originally held up, presumably after getting word from Montgomery that the Washington office steadfastly opposed any censorship at the local and state levels.34

The controversy over what to do with the material coming out of the Charleston FWP office did not end there. In June 1937, Montgomery, who also believed that African Americans were predisposed to fabrication, wrote Murray about a story that black interviewer Augustus Ladson had sent state Negro FWP supervisor Elise Jenkins. In it, ex-slave Susan Hamilton asserted that enslaved women were given very little time to recover after childbirth. “Dey deliver de baby ’bout eight in de mornin’ an’ twelve had too be back to work,” the former bondwoman had told Ladson. Montgomery inquired whether Murray, as Charleston district director, could pay a visit to Hamilton and re-interview her, pretending that he had not read Ladson’s account. She wanted to see if Hamilton would repeat the story, noting that if she did “it probably is true” and warranted being forwarded to Washington. Although the national FWP office had instructed them to send all stories “as is,” Montgomery added that in her “opinion this statement needed verification.”35

Ex-slave Susan Hamilton spoke of slavery’s cruelties in her conversation with Augustus Ladson, a black Federal Writers’ Project interviewer.

A few days later, Murray responded that he, too, had grave concerns about Hamilton’s statement regarding the treatment of enslaved mothers in the antebellum South. “It is my opinion that she made up a great part of the tale out of the whole cloth, apparently being glad of the opportunity to give vent to her bitterness,” he wrote. Once again, Murray juxtaposed ex-slave testimony against more trustworthy white sources—this time William E. Woodward’s 1936 A New American History. “You may recall that he points out the fact that most of the stories about cruel and inhuman treatment of slaves were sheer propaganda,” he wrote Montgomery. Murray agreed that Hamilton should be interviewed again, though not by him, as Montgomery had requested, but rather by a white woman.36

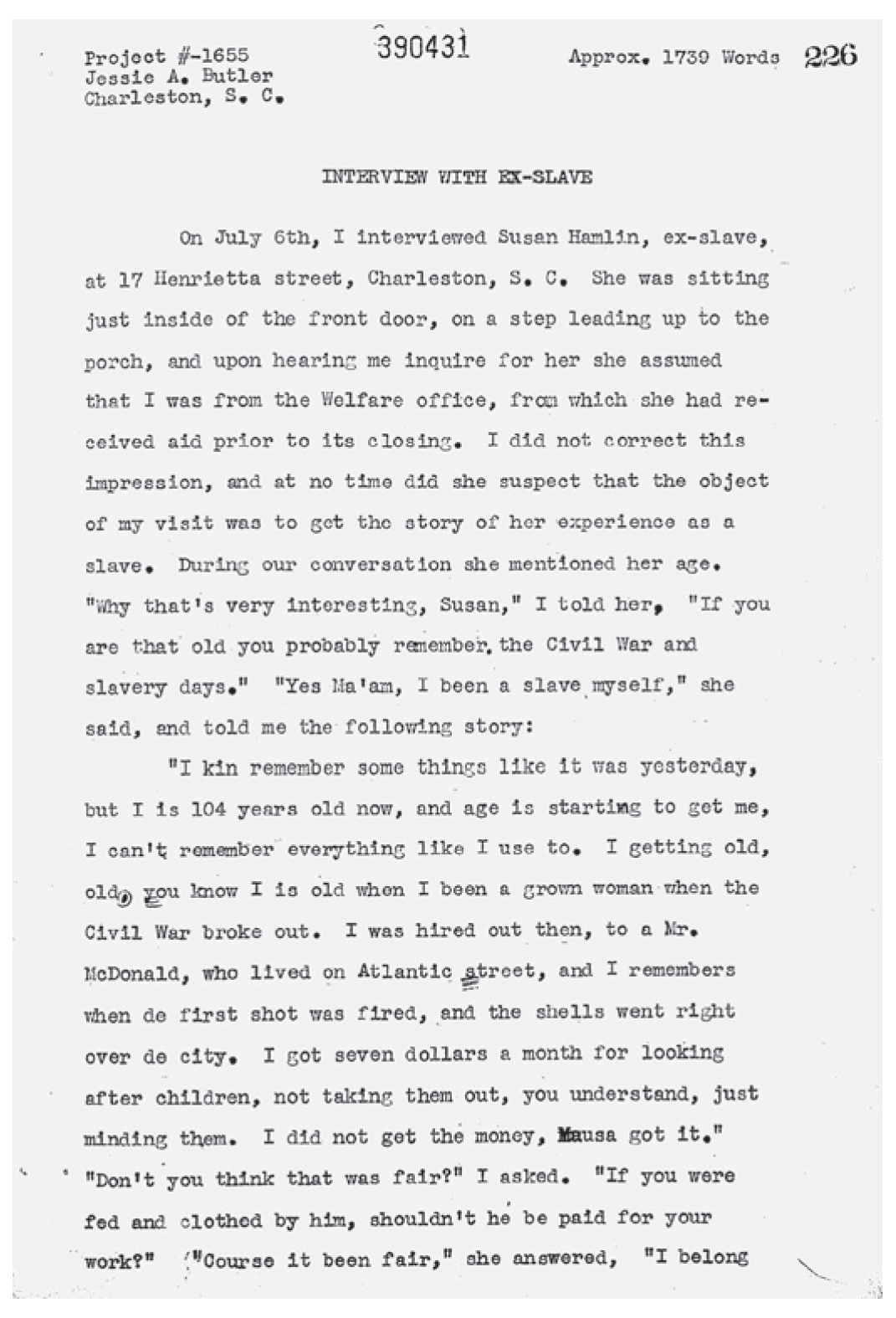

Suspicious of what Hamilton told Ladson, Federal Writers’ Project staff sent Jessie Butler, a white woman, to re-interview her in hopes of eliciting a more positive spin on slavery.

One week later, Murray forwarded to the Columbia FWP office the first of two interviews that white FWP interviewer Jessie A. Butler conducted with Susan Hamilton. “It is a remarkable story—in fact one of the best of its kind that has been turned in so far,” he told Montgomery. “It is doubly remarkable because it flatly contradicts almost all of the statements in the article filed by the negro worker Ladson.” Murray was right on one front. Ladson and Butler agreed on a few basic facts, but as a whole their accounts are a study in contrasts. Ladson’s narrative portrays slavery as characterized by exploitation and suffering. Hamilton told him that her brother was her master’s illegitimate son. She also related the story of a hot-tempered washerwoman named Clory, who was savagely beaten after throwing her mistress out of the laundry for criticizing her work. The trauma of the auction block was ever present. “All time, night an’ day, you could hear men an’ women screamin’ to de tip of dere voices as either ma, pa, sister, or brother wus take without any warnin’ an’ sell,” she informed Ladson.37

In her interview with Butler, however, Hamilton made a point of avoiding generalizations about slavery, while at the same time describing her personal experiences in neutral, even positive, terms. Many of her comments focused on her owner, Edward Fuller, who barely appeared in Ladson’s account. “Seem like Mr. Fuller just git his slaves so he could be good to dem,” she told Butler. There is no mention in the Butler interview of a relationship (forced, coerced, or otherwise) between Fuller and her mother, or of Clory being whipped. Hamilton even implied that the pain suffered by mothers who lost children to the slave trade was exaggerated. “Sometimes chillen were sold away from dey parents. De Mausua would come and say ‘Where Jennie,’ tell um to put clothes on dat baby, I want um. He sell de baby and de ma scream and holler, you know how dey carry on.”38

What is noteworthy about Butler’s interview is neither that Murray judged it one of the best so far (after all, he had been looking for less macabre memories of slavery) nor that it contradicted so much of what Ladson had recorded. It is, rather, that Murray could have read it and still come to the conclusion that Ladson was the only one who had acted unprofessionally. According to Butler’s narrative, Hamilton appears to have offered a damning account of her conversation with Ladson, suggesting that he shaped the ex-slave’s responses to suit his own ends. “A man come here about a month ago, say he from de Government, and dey send him to find out ’bout slavery,” she said. “He ask me all kind of questions. He ask me dis and he ask me dat, didn’t de white people do dis and did dey do dat.” Hamilton informed Butler that she had readily accommodated Ladson—giving him “most a book”—yet he had given her only a dime in return. Butler’s narrative convinced Murray that the black FWP writer had not only asked Hamilton “leading questions” but also “literally put the words in her mouth.” Fortunately, Murray concluded, Butler had been “perfectly fair in the way in which she put her questions.”39

Butler’s narrative, in fact, demonstrates quite the opposite. When Butler first visited Hamilton at her Henrietta Street home, the former slave assumed that her white visitor was from the recently closed welfare office, from which she had been receiving support. In an attempt to conceal her true reason for being there, and thereby, in her mind, to elicit more candid testimony, Butler chose not to disabuse Hamilton of this misconception. Yet this subterfuge surely undermined any possibility of gleaning the truth. In an era when few black southerners felt comfortable talking openly (or, at least, negatively) about slavery when among whites, Butler compounded the problem by giving Hamilton economic incentive not to say anything that might upset her white guest. Then, there were Butler’s questions. Hired out as a nursemaid, Hamilton had had to give her monthly earnings to her master. “Don’t you think that was fair?” Butler asked early in the conversation. “If you were fed and clothed by him, shouldn’t he be paid for your work?” Well primed, the elderly ex-slave replied, “Course it been fair. . . . I belong to him and he got to get something to take care of me.” Butler lobbed such leading questions again and again over the course of the interview. “Were most of the masters kind?” she asked. “Did they take good care of the slaves when their babies were born?” No doubt an expert in this Jim Crow give-and-take, Hamilton told Butler (and Murray and Montgomery) just what they wanted to hear.40

Still, despite their reservations, Murray and Montgomery failed to censor Augustus Ladson’s work. When John Lomax visited the Columbia FWP office in July 1937, the same week he recorded the Plantation Echoes in Charleston, Montgomery shared Ladson’s interview as well as Butler’s with the folklore editor. Lomax suggested that she send both accounts to FWP director Henry G. Alsberg along with all her correspondence with Murray on the issue. Alsberg’s exact response to the materials Montgomery forwarded him is uncertain, but we do know that they did not induce him to disregard either narrative. Instead, both interviews with Susan Hamilton appear in the final FWP ex-slave narratives collection, which were processed and preserved by the Library of Congress’s Writers’ Project.41

Inadvertently, then, Murray and Montgomery have done scholars of historical memory a great service. By commissioning separate interviews with the same former bondwoman, one conducted by a black and the other by a white writer, they provide a clear example of how memory is rarely, if ever, an unmediated window in the past, but rather is something that is shaped by the concerns of the present. More generally, the FWP ex-slave narrative program—in both Charleston and the rest of the South—ensured the survival of thousands of individual stories of slavery, many of which, like the material collected by Frederic Bancroft, posed a fundamental challenge to the dominant narrative about slavery in the early twentieth century. “Whether the narrators relate what they saw and thought and felt, what they imagine, or what they have thought and felt about slavery since, now we know why they thought and felt as they did,” wrote Benjamin A. Botkin, who succeeded John Lomax as FWP folklore editor, in the introduction to the Library of Congress collection. “To the white myth of slavery must be added the slaves’ own folklore and folk-say of slavery.”42

* * * *

FEW TOURISTS WHO ventured to Charleston in the interwar period would have had such intimate conversations with former slaves. But countless visitors were fascinated by the notion that the quaint buildings they found in the historic district had once played host to auctions of enslaved men, women, and children. While many white Charlestonians were unsettled by this interest, local businesses saw no reason not to capitalize off this darker portion of their city’s past. As we saw in chapter 6, merchants sold counterfeit slave badges and postcards of buildings associated (accurately or not) with slavery and the slave trade. The Old Slave Mart was marketed as a must-see attraction. In 1924, Furchgott’s Department Store purchased a full-page advertisement in the Charleston Evening Post that included short summaries of the sites that visitors to Charleston could see before taking a break at its King Street outlet. The Chalmers Street slave market was the first point of interest the advertisement featured, locating it in the top left-hand corner of the ad. These souvenirs and advertisements worked. In the early twentieth century, a steady stream of tourists re-created the 1865 pilgrimages of abolitionists who had combed the city’s slave-trading district in search of relics. One 1920s postcard observed that the Old Slave Mart “attracts thousands of visitors annually.”43

Miriam Bellangee Wilson knew this perhaps better than anyone. Born in Hamilton, Ohio, in 1878, Wilson grew up poor after her father, James, a Union Army veteran and railroad agent, died when she was just fourteen months old. As a young woman, she took night classes at Toledo University and dreamed of becoming a physician. The need to support her invalid mother, however, forced Wilson to pursue other opportunities, including skippering boats on the Great Lakes, running a tea room in Kansas City, and working for state and federal employment agencies in Toledo. In June 1920, Wilson took a temporary position in Columbia, South Carolina, to investigate employment conditions there. She completed her work by the end of the year and then decided to take a Christmas vacation with a few friends in Charleston. She never left. “The charm of the South appealed to my southern blood,” explained Wilson, whose paternal grandparents had lived in Virginia.44

The newcomer soon became active in Charleston’s burgeoning tourism industry. Working for the Chamber of Commerce, Wilson helped lure snowbirds who might stop off as they traveled home from Florida and produced a popular city map and walking tour guidebook. In 1926, she founded Colonial Belle Goodies, a confectionery that made traditional sweets and delicacies, including peach leather, benne wafers, pralines, and monkey meat cakes. At first, Wilson operated her shop on a shoestring budget, but over time she turned Colonial Belle Goodies into a modest success, shipping her confections across the globe and attracting prominent customers, including automobile magnate Henry Ford. She sold her treats at a variety of locations around the city, including the Anchorage, an antiques shop that she and a partner opened in “an olde pirate house” at 38 Queen Street.45

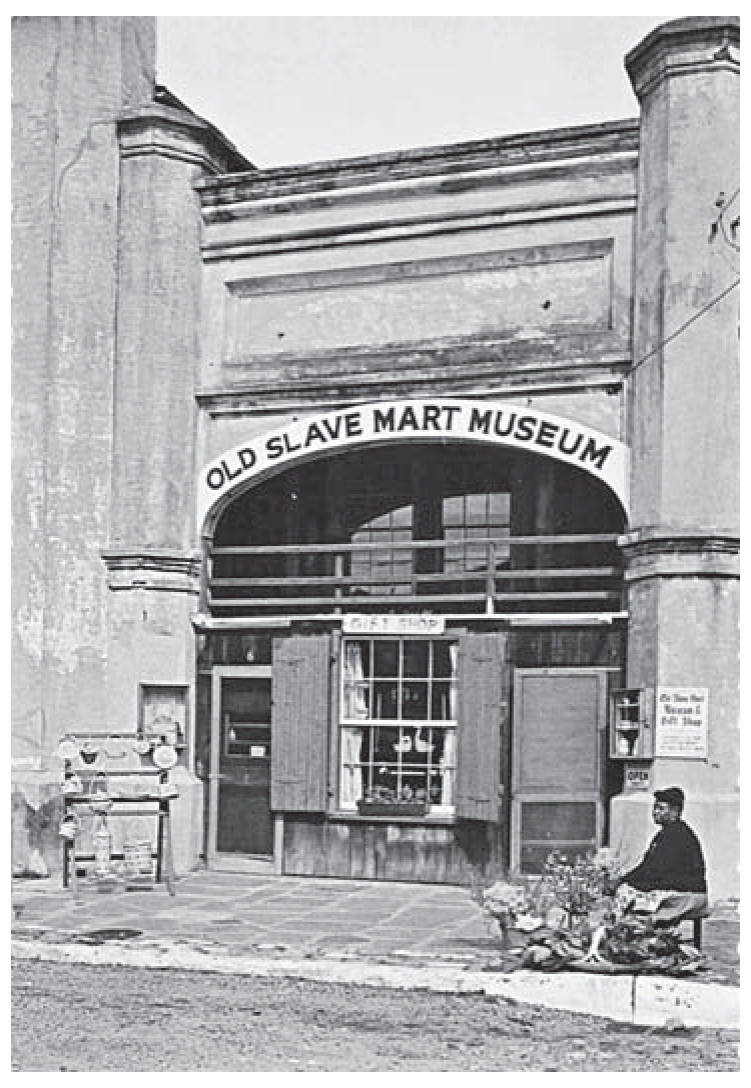

The former Ryan’s Mart became the Old Slave Mart Museum in 1938. It was the first, and for much of the twentieth century the only, slavery museum in the United States.

Just a block away from the Anchorage lay the Old Slave Mart. Over the years, Wilson had observed scores of visitors meandering along its cobblestone street, stopping and staring at the rundown building. Although native whites often disputed the property’s slave-trading history, Wilson researched the site and became convinced that it had, in fact, been a part of the city’s antebellum slave market. By the mid-1930s, she had decided to purchase the 6 Chalmers Street property and turn it into a museum focusing on American slavery. After scraping together $300 for a down payment and spending several months restoring the space, Wilson, at the age of fiftynine, formally opened the Old Slave Mart Museum (OSMM) for business on February 21, 1938. From 1938 until 1959, this institution, owned and operated by a northern transplant, did more to shape Charleston tourists’ understanding of slavery than any other site.46

As the first—and, for much of the twentieth century, the only—museum in the United States focused on the history and culture of enslaved Americans, the OSMM was located in what Wilson and her successors marketed as the last remaining building in Charleston where slaves had been sold. Wilson turned the first floor of the building into a gift shop. She also moved her Colonial Belle Goodies operation there, packaging, selling, and shipping confections, which she now advertised as being based on slave recipes. The dark, drab second floor housed the OSMM exhibits, which featured slave-made arts and crafts as well as several interview stalls, where, Wilson claimed, prospective buyers had examined human chattel.47

Miriam B. Wilson, an Ohio native who relocated to Charleston and opened the Old Slave Mart Museum, displayed slave-made artifacts on the second floor. Although some white Charlestonians questioned her aims, Wilson toed the local white line on slavery.

Until Wilson’s death in 1959, the OSMM was virtually a one-woman show. “Miss Wilson,” wrote Mark Harris, a Negro Digest reporter who visited in 1950, is “curator, chief ticket-taker, and sole lecturer at the Museum.” She was a “mousy little lady,” with large eyeglasses that made her appear like a small owl, recalled an acquaintance from the 1950s. Initially, Wilson offered her lecture each hour between nine and six and charged twenty-five cents for admission. By the 1950s, she had cut back the OSMM’s hours of operation and increased the entrance fee to fifty cents. Wilson estimated that more than 10,000 people from across the world toured the OSMM annually.48

Wilson typically kept the OSMM open for nine months a year, closing her doors only in the hot and humid summer months when tourist visits slowed. She spent many summers devouring books and manuscripts relating to slavery at universities and libraries, including Yale, Harvard, and the University of North Carolina. Wilson filled dozens of notebooks with excerpts from newspapers, city publications, and scholarly monographs. The OSMM curator also devoted several summers to scouring the southern countryside in search of slave-made arts and crafts. These expeditions took her to every corner of the South, from Virginia to Texas, Kentucky to Georgia. Wilson enlisted local newspapers to publicize her search, and she claimed that she took advantage of the fact that a few slaveholders and former bondpeople were still alive to verify that the items she had acquired were, in fact, authentic. Eventually, Wilson added handmade bricks, tools, bedspreads, cover lids, rice-fanning baskets, furniture, quilts, copper pans, and slave badges to the OSMM collection.49

At a time when women involved in preservation and historical tourism faced significant obstacles, Wilson struggled more than most. While cultural elites like Susan Pringle Frost and Nell Pringle put their family names and resources on the line as they restored and preserved historic homes in Charleston, Wilson, a northerner who lived alone in a one-room apartment, had to keep her museum solvent without any sort of safety net. Initially, she used the approximately $2,500 a year she collected in admissions fees to cover her monthly mortgage and other expenses, purchase artifacts, and provide assistance to elderly black residents. Even after Wilson paid off her building note in 1945, the museum’s finances remained tight.50

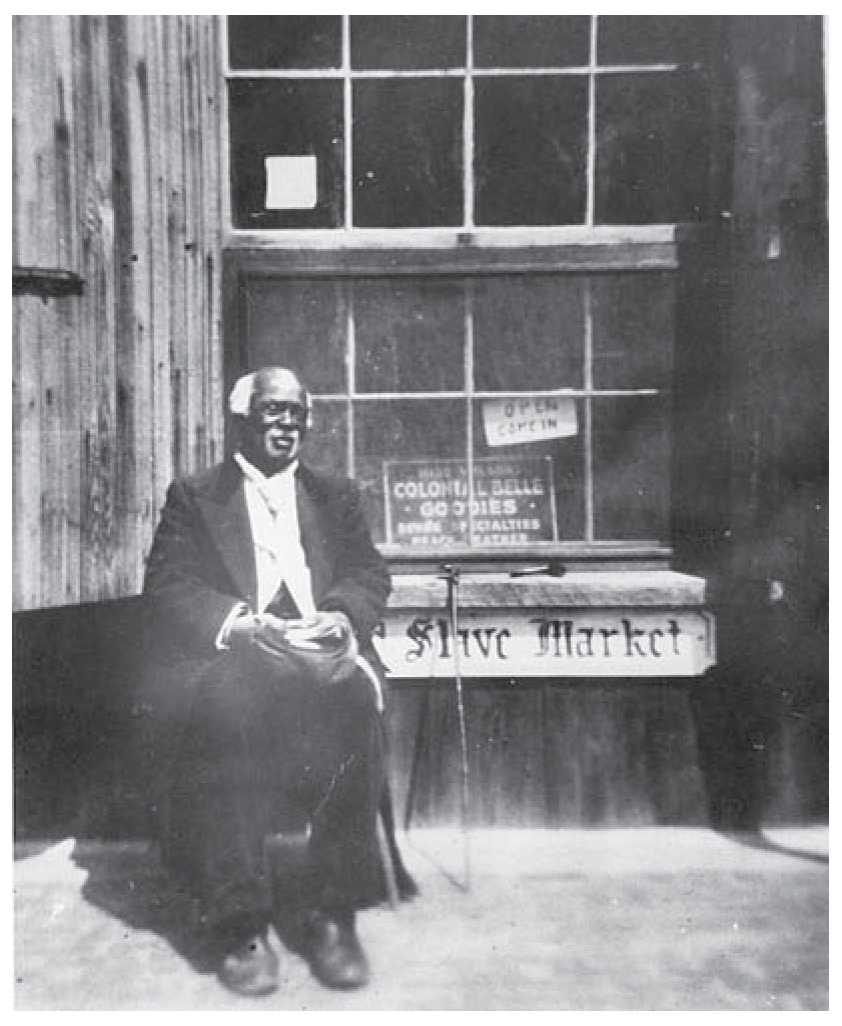

Wilson labored in vain to gain external support for the OSMM and related projects, applying unsuccessfully for fellowships from the Guggenheim and Rockefeller foundations, the Rosenwald Fund, the Blue Ridge Cultural Center, and the Eugene F. Saxton Memorial Trust. Still, Wilson was resourceful. Well into her sixties, she made her own display cases, crafted museum labels, and even installed an electrical system and fluorescent lighting. To bolster interest in the OSMM, Wilson advertised in local newspapers and on radio broadcasts, hosted performers, such as Gullah impersonator Maria Ravenel Gaillard, sold flowers, and offered handwriting analysis services. She also produced postcards of the OSMM, including one that featured a picture of Elijah Green, the ex-slave who had been interviewed by FWP writer Augustus Ladson and who sat in front of the museum each day telling stories of bondage until he died in 1945.51

Wilson worked hard not only to keep the OSMM afloat for two decades but also to defend it against local detractors. Early on, her interest in, and queries about, the sensitive subject of slavery ruffled white Charlestonians’ feathers, particularly because “a Yankee was doing the asking.” The OSMM seemed to threaten the idealized image of the Old South promoted by boosters, preservationists, and groups like the SPS. Locals questioned the authenticity of Wilson’s site throughout her tenure. Some spread “slanderous tales” about Wilson and her museum. According to the most outlandish, Wilson “used to go out and buy raw meat from a butcher shop so that she could smear the blood on the floor and show it to tourists as the ‘blood of the slaves’!”52

Former slave Elijah Green, interviewed by Augustus Ladson for the Federal Writers’ Project, was a constant fixture at the Old Slave Mart Museum until he died in 1945.

* * * *

TRUTH BE TOLD, Wilson’s critics had little to fear. She did spend a great deal of time authenticating her claim that the building at 6 Chalmers Street had once been used for human trafficking by scrupulously compiling information about the property. Yet this research did not lead the northern transplant to construct a museum that emphasized the exploitative sides of slavery. Indeed, by the time she opened the doors to the OSMM in 1938, Wilson had abandoned her early misgivings about slavery and embraced the local party line.53

“When I went to Charleston I was just as ignorant as any other Northerner,” Wilson told a Virginia reporter in the 1950s. The daughter of a decorated Union veteran, she had grown up in Ohio reading stories such as Uncle Tom’s Cabin. And Wilson took great pride in her family’s antislavery sentiments. She boasted that her paternal grandfather, Robert Wilson, had not only left Virginia for Ohio because of his deep opposition to the institution of slavery but thereafter was active in the Underground Railroad. Although Wilson never disavowed her antislavery heritage, she became sympathetic to the white southern perspective while living in Charleston. Her transformation was so complete, Wilson told a reporter in 1948, that around town “she is called a ‘Yamdankee’ rather than a ‘DamYankee’ because of her intense love and sympathy for the South.”54

Wilson’s newfound perspective was not a crass accommodation to popular opinion, nor was she simply catering to tourists’ tastes. Instead, by the time Wilson purchased the Old Slave Mart in 1937, she had become a true believer. Perhaps the most important factor in Wilson’s conversion was her trips to nearby plantations and conversations with their former owners. In 1927, she visited Mullet Hall Plantation on Johns Island with a senior member of the Legare family, which had owned it for generations. Highlighting the struggles of the former planter class in a letter to her mother, Wilson emphasized how enjoyable this veritable trip back into the past had been, especially when she observed the reunion between Mrs. Legare and “her old servants and plantation hands.” Wilson noted that “they were all so delighted to see their Ol’ Missis, and she them.” Decades later, she attributed her strong interest in history to such early interactions with elderly white southerners. They “had grown up on plantations and had been through the War Between the States and its aftermath,” she explained in 1956. “The stories they told stirred my imagination and still linger.”55

Little wonder that when she opened her museum Wilson underscored the challenges that plantation masters and mistresses faced, while also embracing the trope of the faithful slave so ubiquitous in elite Charleston circles. One of the stalls on the second floor of her museum featured replicas of two slaves, Aunt Cylla and Uncle Pink, who would not abandon their owners during the Civil War. Wilson also dedicated the third edition of Slave Days, the published version of her museum tour that she sold as a pamphlet, to “the memory of the loyal faithful negroes who, during and after the war between the states remained faithful to their former owners.” And like the Society for the Preservation of Spirituals and other white spirituals groups, Wilson had a paternalistic understanding of her work at the OSMM. “When one sees the beautiful things that they did during slavery, and how these crafts have been lost, it is a shame to deprive posterity of this knowledge,” she wrote in 1950.56

Wilson found scholarly validation for these nostalgic memories in the academic works that she pored over in the 1930s and 1940s. She was particularly enamored with the scholarship of Ulrich B. Phillips. Wilson urged OSMM visitors to read the southern historian’s work, and her own Slave Days pamphlet drew on it extensively. In 1951, she made a pilgrimage to New Haven to examine the slave manuscript collection that Phillips had bequeathed to Yale University, calling the trip “the most enjoyable six weeks I have ever spent.” Two years later, Wilson received a letter from an Air Force captain stationed in Puerto Rico, requesting to borrow a copy of Phillips’s American Negro Slavery, no doubt a reflection of the emphasis she put on the book in her OSMM tour. Wilson even gave Phillips the last word on slavery in her tour pamphlet, quoting the final paragraph of American Negro Slavery at the end of Slave Days.57

Influenced by Phillips’s work and the reminiscences of local planters, she downplayed local participation in human trafficking, despite her insistence that her building had once been part of a slave-auction complex. In the 1946 edition of Slave Days, Wilson held that “in some sections of the South there was very little speculating in slaves.” Slave purchases in these areas did not reflect a desire to profit from a trade in human flesh, she insisted, but rather the need to replace a labor force depleted by disease or to settle estates. “Research shows that in many sections it was a matter of pride with the planters never to buy or sell a slave,” Wilson wrote. “In fact, there are numerous records showing no slaves bought or sold within one hundred years.” Wilson made it clear what part of the South she meant, once telling a Tennessee reporter that slave auctions “were seldom held in Charleston because owners did not like the idea of selling their slaves.”58

Wilson tried to soften the slave trade’s sharpest edges, too. The 1956 edition of Slave Days included a copy of a handbill advertising the 1852 sale of twenty-five enslaved laborers, twelve of whom were under the age of ten. Yet Wilson tempered this message with a caption stating that the slaves were sold together as families. Wilson also strove to undercut the idea that slavery itself was inhumane, arguing that the horrors of the institution, at least as practiced in the Old South, have “been greatly overstated.”59

Wilson even went so far as to try to discredit visual evidence that testified to slavery’s cruelty. “Pictures showing Negro drivers (sub-overseers) with whips in their hands do not necessarily mean that whips were for use on Negroes,” she declared in Slave Days. Wilson was convinced that there had to be alternative explanations for the scars that the survivors of slavery carried on their backs. “The fact has been established,” she held, “that where the underground railway prevailed, the Negroes themselves would cause injuries to rouse the sympathy of those who were helping them to escape.” When Grace and Knickerbacker Davis, writers from Germantown, Pennsylvania, toured the OSMM in early 1941, Wilson told them that the scars were “the remains of tribal tattooing inflicted before transportation to America.”60

More generally, Wilson cast slavery as a labor system that rewarded the enslaved with the gift of civilization. Planters may have enjoyed the fruits of their slaves’ labor, but they reciprocated by providing food, shelter, and housing for their charges. The artifacts that she displayed in the OSMM reinforced this narrative, offering tangible evidence of the lessons slavery had taught. So, too, did the emphasis that Wilson put on slaveholder manumission, which she suggested was far more prevalent in the Old South than the sale of slaves. And her portrayal of emancipation and Reconstruction only bolstered her message. To her mind, “the crime against the Negro was not that he became our slave, for they had always known slavery in some form. . . . The crime against the Negro was turning them loose without proper guidance.” In other words, the true tragedy to Wilson was that the Civil War and its aftermath had interrupted the civilizing process inaugurated under slavery before its work was complete.61

Wilson believed that by teaching Americans about the black past, the OSMM could help rectify the social problems of the present. “My museum was founded for the purpose of saving specimens of all the crafts that the Negroes became proficient in doing during Ante-bellum days,” she wrote the president of the Tuskegee Institute after touring the Alabama school in 1948. “The lecture I give is to try to bring about a better understanding between the two races, so that we can be mutually helpful to each other.” Wilson deemed the average white person ignorant of the challenges blacks faced, while she thought that others sought to exploit African Americans or were misguided by sentimentalism. And blacks, to her mind, were apt to view the enslaved past with embarrassment. In contrast, Wilson insisted that she approached the race question from a practical perspective—much like the Tuskegee Institute’s founder, Booker T. Washington.62

Wilson, in fact, was a strong proponent of Washington, whom she called “the greatest leader the Negroes ever had.” She displayed a picture of Washington, who had died in 1915, in the OSMM and praised his accommodationist program as an invaluable alternative to the civil rights agitation of the postwar era, which she steadfastly opposed. In her 1946 Slave Days pamphlet, she maintained that “the Negroes who are following his teachings are accomplishing much more for the race” than those working for equal rights. Wilson’s civilizing interpretation of slavery dovetailed with Washington’s emphasis on gradual change, industrial education, and black self-help. By highlighting the great strides made by the enslaved, the museum operator believed she was helping black and white Americans to see what was possible in the Jim Crow South.63

Tourists from across the country appear to have appreciated Wilson’s lessons, writing her letters of thanks for what she taught them about slavery. “We felt as though we were transferred to another (more exciting) world,” effused a New Jersey housewife after visiting the OSMM with her family in 1952. “I feel the Old South thrills everyone but no one can realize just how thrilling it must have been until they hear you.”64

Not every visitor, however, was pleased by what they saw and heard at the OSMM. One spring evening in the late 1930s or early 1940s, sociologist Katharine Du Pre Lumpkin stumbled upon Wilson’s museum while strolling through town. Although a native Georgian and the daughter of a Confederate veteran, Lumpkin had come to reject the Lost Cause mythology upon which she had been reared. Peeking inside the heavy door of the OSMM, Lumpkin was struck by the place’s incongruity with its past. As she wrote in her 1947 autobiography, “What once had seen the buying and selling of slaves now welcomed the visitor to a tidy, almost gay souvenir shop selling candy and postcards and knickknacks.” Lumpkin was not able to tour the museum—it was closed for the day—but she was put off by Wilson’s brief description of her approach to the slave past. Noticing the stairs that led to the second floor, where the museum’s collection was located, Lumpkin asked what she would find up there. Wilson replied sharply, “only pleasant reminders. We don’t go in for slave horrors.”65

A few years later, Negro Digest writer Mark Harris wrote a sarcastic send-up of what he had learned on his 1950 visit to the OSMM. Although this Jewish New Yorker found Wilson charming and expressed appreciation for her preservation efforts, he laid bare myriad misgivings about her characterization of slavery. Clear-eyed visitors “may not agree that slave-owners met their responsibilities to their slaves with ‘kindness and courage,’” Harris maintained. “They may doubt her judgment that the crime against Negroes was not that they were enslaved but they were too hastily freed,” and “they may flinch at her assertion that the Federal ban on slave-importation in 1808 was a positive evil.” But “these are small points,” Harris concluded with his tongue firmly planted in his cheek. “When in Charleston do as Charleston does! You’ll get along better that way.”66

As if to head off such critiques, Wilson made a point of highlighting the popularity of the OSMM among African Americans. Black educators who had visited the museum “all speak highly of the work I am doing,” she claimed in 1941. Thirteen years later, Avery graduate Ethelyn M. Parker told Wilson that the OSMM “really has a wonderful future.” Yet Parker added, “most of my people do not relish the idea of carrying on the slavery idea.”67

However much other African Americans shared this disinterest, some black South Carolinians did, in fact, visit the OSMM. In April 1956, seventy undergraduates and two teachers from historically black Morris College in Sumter made a trip to Wilson’s museum, when it hosted a special exhibit of watercolors depicting slave handicrafts. Millicent Brown, the daughter of the Charleston NAACP chapter president, took regular field trips to Wilson’s museum while she was a student at all-black A.B. Rhett Elementary School in the 1950s. Reflecting back on these experiences a half century later, Brown was struck by how little she learned. The museum was a mishmash of artifacts displayed in glass cases. And Wilson did not seem to take much interest in providing context for what Brown and her classmates were seeing. The little that Wilson did say about slavery, Brown recalled, left the impression that she was not sympathetic to the experiences of the enslaved or their descendants.68

* * * *

WILSON SPENT A good portion of the late 1940s and 1950s working on a historical novel that she believed would spread the OSMM’s message about slavery throughout the United States. According to her notes, “Oogah” would follow the rise and fall of an African prince who, after being captured by slave traders and brought to the Old South, thrived on a southern plantation only to struggle when he and his family were freed without sufficient guidance. Yet Wilson’s work at the OSMM afforded her little time to write, and she died on July 8, 1959, before she could complete her novel. She remained an outspoken opponent of civil rights to the end.69

Wilson bequeathed the OSMM collection and the 6 Chalmers Street property to the Charleston Museum, which declined both. The OSMM and its contents ultimately ended up in the hands of Wilson’s good friend Louise Alston Graves and her sister Judith Wragg Chase. Though born in New Jersey and Georgia, respectively, the sisters—who came from several old-line Charleston families and counted DuBose Heyward a cousin—settled in Charleston in the mid-twentieth century. Graves and Chase thought the OSMM was a treasure that must be preserved. Fearing that it might be torn down, they made arrangements to lease the building and reopened the museum in November 1960. Several years later, the sisters bought the building and its contents.70

Graves and Chase made minor improvements to the OSMM, but tried to stick closely to Wilson’s vision. “Whatever we do, however, we don’t plan to stray from Miss Wilson’s original objectives,” Chase told a reporter. A few years after taking over the museum, Chase explained what this fidelity looked like. In a 1963 letter lobbying the city to install a sign pointing the way to the OSMM, she informed the chairman of Charleston’s Commission on Streets that “since tourists to the South are always interested in the subject of slavery, whether we like it or not, we feel we are doing the South a favor by presenting the History of Slavery in an objective way. Day in and day out we help to correct erroneous and uncomplimentary ideas gained from such books as ‘Uncle Tom’s Cabin’ and to give our visitors a more tolerant viewpoint of the problems that beset the South during Slavery.”71

While Graves and Chase kept Wilson’s mission alive, another segment of Charleston began deploying the black past in a significantly different fashion. Just weeks after Judith Chase wrote these words, in fact, civil rights protesters launched the Charleston Movement to contest the racial barriers that African Americans faced in the city more than a century after emancipation. In the process, they not only cast off the Jim Crow veil that had concealed black memories of slavery for decades, but also enlisted those memories in their new fight for freedom.