IN EARLY JUNE 1963, A SERIES OF NAACP-ORGANIZED boycotts, marches, and sit-ins punctured Charleston’s preferred atmosphere of genteel calm. Hundreds of African Americans, mostly students, participated in the Charleston Movement, demanding the desegregation of public schools and public accommodations, fair employment, and the creation of a biracial committee to tackle future problems. By early July, arrests totaled over five hundred, though violence remained at bay. Democratic Mayor J. Palmer Gaillard Jr. and the police chief made sure of it, hoping to prevent another Birmingham, where just two months earlier vicious attacks on protesters by police dogs and firehoses had led to international outrage. On July 7, NAACP national director Roy Wilkins spoke before a capacity crowd at Emanuel A.M.E. Church, a base of operations for the protests, observing that while segregation in Charleston may have been “peaceful and graceful,” it mattered little. “Castor oil tastes as bad with a little orange juice as with nothing at all.”1

Events came to a head on July 16, when a crowd of five hundred gathered outside the News and Courier offices at the corner of King and Columbus streets to denounce editor Thomas “Tom” R. Waring Jr.’s hardline position against desegregation. Having assumed the editorial reins of the News and Courier from his uncle William Watts Ball in 1951, Waring had led the chorus of white resistance to the black freedom struggle in the Lowcountry for more than a decade.

Asked at one point by the police to stop the singing of freedom songs during their vigil outside the newspaper office, the activists refused. As they confronted one of the most formidable figures of white supremacy in the city, Charleston Movement participants were loath to give up the songs that had proved a potent source of inspiration and camaraderie throughout their campaign. Since the beginning of the protests in June, activists had sung freedom songs—including old slave spirituals—as the police hauled them off to jail. Lindy Cooper, a liberal, white Charleston teenager who watched the demonstrations that summer, remembered witnessing arrests after a boycott of King Street stores. Protesters started drumming on the sides of the paddy wagon and then sang “Come En Go Wid Me.” Cooper knew the Gullah spiritual as one the Society for the Preservation of Spirituals liked to perform. But the King Street protesters altered the song to fit their circumstances: “They were saying instead of ‘if you want to go to heaven, come and go with me’ it was ‘if you want your freedom, stay off King Street.’”2

This political use of slave spirituals was not new. Back in 1945, when more than one thousand workers at Charleston’s American Tobacco Company Cigar Factory went on strike, they, too, looked to the slave past as a source of power. Led by Lucille Simmons, a black laborer with a captivating alto voice, the striking workers sang “I Will Overcome,” based, in part, on a Lowcountry slave spiritual known as both “Many Thousand Gone” and “No More Auction Block.” In the face of police harassment and company intransigence, the workers found the song a source of hope and, along the way, crafted new verses—“we will win our rights,” “we will win this fight,” “we will overcome”—that gave the song greater collective and political meaning. “Someone would say, boy I don’t know how we are going to make it,” striker Stephen P. Graham remembered, “but ‘We’ll overcome someday.’” By the time the Charleston Movement brought America’s Most Historic City to its knees in 1963, a slightly altered version of the tobacco workers’ song, “We Shall Overcome,” had emerged as the unofficial anthem of the civil rights movement, its redemptive message ringing out from protest lines, Freedom Rides, and jail cells throughout the South.3

During Jim Crow, the public memory of slavery in Charleston had been a white one—constructed on concert stages, in tourism guidebooks, and at sites like the Old Slave Mart Museum. As the civil rights movement gained momentum in the postwar period, African American activists in the city and surrounding Sea Islands pushed their own memories of the peculiar institution into the public sphere for the first time in decades. Their aim was, in a sense, simple: they hoped to make the Low-country’s history more accurate and inclusive. But the African American determination to remember slavery was about more than just a desire to overcome historical amnesia. It was about finding a usable past. Activists harnessed the memory of slavery to animate their fight against Jim Crow, transforming memory into a source of power.

* * * *

THE 1945 TOBACCO workers strike signaled a new day in Charleston, as in the rest of the South. The walkout was an early indication of how rising black expectations in the post–World War II era would shatter the foundations of Jim Crow. Over the next decade, the black assault on the racial status quo became a mass movement. Galvanized by the NAACP’s victory in the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education decision, which ordered the desegregation of public schools, activists all over the region took aim at the system of racial apartheid that white southerners had imposed in the late nineteenth century. In places like Birmingham, peaceful protesters took to the streets to demand the integration of public facilities, the hiring of African Americans, and the end to discriminatory voting measures.4

The backlash at every turn was daunting. White southerners countered the court order to desegregate with a program of massive resistance, instituting creative compliance plans that allowed for minimal, token integration while threatening black parents who dared to push the issue too much. Other forms of reprisal were more malicious. Despite being dedicated to the moral and strategic advantages of nonviolence, civil rights protesters were hauled off to jail, confronted by angry mobs, assaulted with rocks and brickbats, and, sometimes, murdered for their activism.5

Still, black southerners and sympathetic whites triumphed, to a degree. If true economic justice remained elusive—and structural racism more difficult to eradicate—the victories were nevertheless real. Pushed by activists, Congress passed the Civil Rights Act in 1964, which outlawed segregation in public accommodations and employment, and the Voting Rights Act in 1965, which swept away the discriminatory measures whites had long used to disenfranchise black southerners. By the mid-1960s, life in the South had been fundamentally altered.6

In America’s Most Historic City, the 1963 Charleston Movement represented the culmination of local civil rights agitation, building not just on the earlier tobacco workers strike but also on a series of direct action campaigns in 1960 and 1962. By September 1963, the Charleston Movement had won some important victories, such as the establishment of the biracial committee, a promise of equal employment opportunities, and the desegregation of restrooms and water fountains. In keeping with his cautious stance throughout the Charleston Movement, Mayor Gaillard, descended from an old-line Huguenot family, accepted the outcome but never voiced eager support for the protesters’ goals. Meanwhile, as the Charleston Movement wound down, a federal district judge ruled in favor of several NAACP plaintiffs and ordered the desegregation of Charleston city schools—nine years after the Brown decision. On September 3, 1963, four formerly all-white schools became the first in the state of South Carolina to open their doors to black students.7

In challenging Jim Crow, black Charlestonians challenged the myth of interracial harmony that whites had nurtured since imposing segregation—and even before. No group had better epitomized this myth—or had done more to perpetuate it—than the Society for the Preservation of Spirituals (SPS). In some ways, the SPS carried on much as it had before, despite the racial unrest roiling Charleston, continuing to perform several times a year. The society maintained its charity program for needy blacks as well, though in 1958 SPS treasurer Henry B. Smythe noted that the society was currently helping only one person, a fact he called “rather ridiculous” given that philanthropy was one of the group’s primary concerns. His fellow spiritualists took heed. By the end of the year, the society had come to the aid of five individuals.8

Part of the problem in allocating sufficient money for its welfare fund seems to have resulted from another long-standing tradition: treating practices as parties. In 1968, the society’s liquid refreshment expenses totaled $529, while its charity expenses equaled $535, prompting another round of soul-searching. The evidence of declining interest that emerged in the prewar years reappeared in the 1950s and 1960s. One solution was a change in the group’s cocktail policy. In 1965, it voted to serve drinks as soon as everyone arrived at meetings, rather than after practice had concluded, in the hopes “that this might result in more prompt attendance, and more enthusiastic singing.”9

Yet the SPS’s records from this era reveal uneasiness over more than just lackluster attendance. Concerns about the assault on segregation permeated the group’s meetings, correspondence, and activities. While SPS members had fretted over the disappearance of old-time “darkeys” for decades, in the post-Brown South these anxieties reached new heights. One member who requested money for a charity case pointed out that the recipient was from a family of “faithful negroes” and a “relict of the Old Regime,” not someone who sympathized with the calls for a new racial order.10

Desegregation and the civil rights movement began to challenge the commonly held understanding of the society’s singing and preservation work, too. By 1956, the changed landscape inspired an acknowledgment, at least by one white Charlestonian, that some observers might find the SPS problematic. That year, a CBS radio producer wrote to John M. Rivers, a Charleston contact, to inquire if he knew of any Lowcountry folk music that could be featured on the network. Rivers recommended the SPS but admitted that “with all of the to do about segregation, there is some question as to whether or not this kind of music or entertainment would be acceptable to your show.” Still, he maintained, the group was unique and “probably more than any other one thing represents the direct affection which the white people of lower South Carolina held and hold for the Negroes in whom they are interested.”11

African Americans, for their part, began to publicly criticize groups like the SPS. In 1959, a Jacksonville, Florida, newspaper ran a piece about an upcoming SPS concert in the city but predicted that if the NAACP had its way, spirituals would “become extinct as the dodo bird.” Since the 1940s, the civil rights organization had sought to improve the way that Hollywood and the emerging television industry portrayed African Americans. This campaign targeted characters, such as Amos and Andy, that reinforced negative stereotypes, as well as stories and songs that used black dialect. The paper regretted that the NAACP was encouraging African Americans to turn their backs on their past and suggested that it was because spirituals were associated with slavery that blacks wanted nothing to do with them. SPS members and like-minded Charlestonians agreed that it was the duty of whites to preserve what blacks would just as soon forget. Artist Elizabeth O’Neill Verner argued in a forceful letter to the News and Courier in 1960 that “the colored people do not appreciate their heritage”—specifically, slave spirituals—but fortunately their white friends did.12

By the early 1960s, many whites took it for granted that civil rights activists frowned upon the SPS and similar performers. A woman who handled arrangements for a 1960 SPS concert in Cheraw, a small town near the North Carolina border, reported to the group that she had “exploited the fact that the N.A.A.C.P. disapproves of your efforts” in the publicity materials for the performance. “You might bear this in mind in future efforts,” she offered, “because I discovered that a number of people who attended on Saturday were there partially because they are so irritated at the N.A.A.C.P.” SPS members, however, were more inclined to see African American criticism as a threat rather than as an unintended boon. In November 1963, on the heels of the Charleston Movement, society officers felt uneasy enough about the “racial situation and our concerts” to meet with Mayor Gaillard, News and Courier editor Tom Waring, and Emmett Robinson, head of the Footlight Players Workshop, where the SPS gave its annual spring performances. “All three gentlemen agreed the concerts should be continued,” SPS president Dr. John A. Siegling reported.13

The racial situation caused headaches in other ways, too. In 1968, the SPS was asked to appear in a documentary on the arts in South Carolina produced by the state Arts Commission. After learning that the commission hoped to acquire federal money to pay for the filming, the society voted to invite one of the producers to a practice, but only “after having checked . . . to determine that there would be no integration problem,” presumably believing that the federally funded project might invite unwanted scrutiny into its unusual form of cultural preservation or its whites-only membership. But filmmakers were the least of the group’s worries. By 1968, the society feared that protests, even violence, might disrupt its shows. That spring, SPS president Siegling requested that police periodically cruise the box offices before two concerts, one at the Footlight Players Workshop in Charleston and another at a theater in Spartanburg, where the society was slated to perform.14

It is entirely plausible, as the Jacksonville newspaper contended, that the black opponents of the SPS wanted to forget spirituals and slavery. As we have seen, some educated, urbanized African Americans rejected spirituals in favor of more formal forms of worship. Moreover, by the late 1960s, when the SPS felt compelled to turn to the police, the rise of the Black Power movement may have cast a pall on the spiritual among more radical civil rights activists, who viewed the genre as antiquated and indebted to a passive model of black resistance. But the recollections of white folk musician and civil rights activist Guy Carawan point to another possibility. Carawan noted that for some younger activists in groups like the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, being exposed to spirituals during these years was a revelation. It was the first time, he said, that they had heard “songs from the days of slavery that sang of freedom in their own way. They began to realize how much of their heritage had not been passed on to them.” The threats to the tranquillity of SPS shows in 1968, in other words, may have come from black civil rights activists who, newly attuned to the history of slave spirituals, objected to the appropriation of spirituals by whites.15

* * * *

GUY CARAWAN HIMSELF played a somewhat surprising role in helping movement participants adapt Lowcountry spirituals to the context of the civil rights struggle. Born and raised in Los Angeles, Carawan was an outsider to the spirituals tradition, though he did have deep roots in the South, even in Charleston. Carawan’s mother, Henrietta Aiken Kelly Carawan, hailed from a prominent Charleston family. Her aunt and namesake, Henrietta Aiken Kelly, founded the Charleston Female Seminary, the Poppenheim sisters’ alma mater. As a child, the younger Henrietta grew up attending St. Philip’s Church and always considered herself a “proud ‘Charlestonian blueblood.’” There is no evidence that she had any special interest in spirituals that she passed on to her son, but Guy’s southern heritage (his father was from North Carolina) stirred his curiosity about the folkways of the region.16

Carawan came of age in the folk music worlds of the West Coast and New York City. As an undergraduate at Occidental College in Los Angeles, he was exposed to folk music, and he later read about Gullah culture while pursuing his master’s degree in sociology at UCLA. During his years on the West Coast in the 1950s, he first heard the most famous song to which Lowcountry blacks helped give rise: “We Shall Overcome.” Carawan learned the song from folk singer Frank Hamilton, who had picked it up from Pete Seeger, who had gotten it from Zilphia Horton, the music director of the Highlander Folk School, a training ground for civil rights activists located near Monteagle, Tennessee. Zilphia, for her part, first heard the song in its earlier form, “We Will Overcome,” from two Charleston tobacco workers—Anna Lee Bonneau and Evelyn Risher. Not long after the Charleston strike concluded, Bonneau and Risher attended a workshop on union organizing at Highlander, sharing the song with Zilphia and other workshop participants.17

By the end of the 1950s, Carawan’s appreciation for Lowcountry music had deepened. In 1959, he became Highlander’s music director, replacing Zilphia after her death. That July, Carawan helped lead a workshop on developing community leadership. Fifty participants, including fifteen from the South Carolina Sea Islands, learned strategies for solving problems in their hometowns. “And such a week of singing I’ve never heard in my life,” Carawan reported. “Old style spiritual singing by the older folks and more modern gospel singing by the younger ones.”18

On the evening of July 31, the final night of the workshop, police raided Highlander as part of a campaign to shut down the school for allegedly fomenting communist subversion. For an hour and a half, as the police searched the premises, the group sang spirituals, including “We Shall Overcome,” adding a new verse, “We are not afraid.” Carawan, Septima Clark (the Charleston-born activist then serving as Highlander’s director of education), and two others were arrested on bogus alcohol charges (Grundy County was dry). Clark occupied a cell next to Carawan’s in the county jail. Through the walls, Carawan heard Clark, who had overcome her adolescent antipathy for slave spirituals, singing “Michael Row the Boat Ashore,” a Sea Island slave spiritual. The song “made me feel better,” he wrote to Pete Seeger and others after the ordeal. “I shortly fell asleep to it and woke up the next morning well rested in spite of the lumpy hard springs.”19

Later that year, Carawan took up temporary residency on Johns Island to help Clark with her Citizenship School program. Founded in 1957 by Clark and Esau Jenkins, a Johns Island activist who had also trained at Highlander, Citizenship Schools helped illiterate blacks learn to read and write so that they could pass South Carolina’s literacy test and register to vote. Carawan’s involvement with Citizenship Schools and his friendship with Jenkins, especially, afforded him unusual access to the Sea Island black community. As Carawan noted, Jenkins was “the most loved and respected ‘grass roots’” leader in the area—the “Moses of his people.” Connecting with such a prominent local, who himself appreciated the music of the Sea Islands, proved profoundly important to Carawan. Jenkins was instrumental in facilitating the folk singer’s exposure to the local corpus of slave spirituals. Along with Sea Island women like Alice Wine and Bessie Jones, Jenkins became a bridge between the songs’ quasi-private use in the African American community and their public use within the civil rights movement.20

In 1959, white folk musician Guy Carawan (playing guitar) went to Johns Island, where he worked to preserve Gullah spirituals. He saw the songs as an untapped resource in the fight against segregation.

In fact, at Jenkins’s invitation, Carawan became the first white person to ever attend the special Christmas service at Moving Star Hall. Congregants gathered at this hybrid communal center, benevolent society, and interdenominational praise house to hear preaching and to shout—a fusion of song, dance, and polyrhythmic percussion that dated back to the ring shout of the enslaved. At the Christmas Watch Meeting, attendees shouted from midnight on Christmas Eve to dawn. What he heard during that 1959 service was “rich and exciting,” Carawan and his wife, Candie, later wrote, and “it brought him back year after year.” It also convinced Carawan that spirituals should occupy a prominent place in Citizenship Schools. He incorporated the songs into the curriculum, adding a singing component to the end of every class in early 1960. Carawan then inaugurated a special spirituals concert to conclude each Citizenship School session.21

According to Carawan, some black Johns Islanders needed help in appreciating the importance of the old slave spirituals, a claim that was not without some merit. The social and demographic forces that had conspired to endanger spirituals since emancipation had accelerated in the post–World War II years, with greater educational and economic opportunities pushing younger blacks away from Gullah culture, if not off the island altogether, and a suburban boom bringing in whites and more urbanized blacks from the city. Although spirituals singing still occurred at praise houses like Moving Star Hall and, on occasion, at other black churches, younger black islanders were not enthusiastic about the shouting at either place. “Why waste time with something that you aren’t gonna get anything out of at all?” asked Black Power activist William “Bill” Saunders, who grew up going to Moving Star Hall. “You gonna be looking forward to when you die, and man, you hungry now.” Saunders and his peers were drawn to contemporary musical styles like soul, rhythm and blues, and gospel. Carawan found that even some older residents had started to back away from spirituals, appearing self-conscious when singing in front of more-educated blacks and whites, like folklorist Alan Lomax, son of John Lomax, who celebrated their per formances.22

Carawan observed that Gullah spirituals singers were genuinely moved to learn that others appreciated their music. They needed no one, however, to tell them what the songs meant, a fact that Carawan understood. When Citizenship School students sang spirituals such as “Been in the Storm So Long,” they shared personal testimonies about how the songs had helped them “overcome their many hardships.” Esau Jenkins explained why older islanders sang spirituals in similar terms: “They’re giving praise to the great Supreme Being who . . . stood by them in the past days from slavery up to the present. . . . Those songs are the ones that made them happy, made them go through those hard days.” In addition to the important psychological function spirituals performed in the daily lives of Johns Islanders, Jenkins and Carawan both predicted, correctly, that the songs might bring more students into the Citizenship Schools.23

Carawan made the case for spirituals as weapons in the struggle for civil rights beyond Johns Island, too. The sit-in movement was raging throughout the South, and at his urging, spirituals became a part of the body of freedom songs that activists sang in the service of their cause. In 1960, Guy Carawan introduced “We Shall Overcome” to members of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) at their founding meeting in Raleigh, North Carolina. Carawan also taught movement activists “Keep Your Eyes on the Prize,” a variation of “Keep Your Hand on the Plow,” which he had learned from Alice Wine, a Moving Star Hall singer, during his visit to Johns Island in 1959. Given their focus on liberation and deliverance, spirituals seemed to Carawan valuable tools of protest at this moment of intense social activism. “So many great old spirituals that express hatred of oppression and a longing for freedom were being left out of this growing freedom movement,” Carawan held. Since activists “were not taking advantage of what their heritage had to offer,” he made it his mission to help them do so.24

A visit to Nashville, which was embroiled in a three-month sit-in campaign in the spring of 1960, encapsulated the challenges inherent in Carawan’s effort. “The first time I remember any change in our songs was when Guy came down from Highlander,” C.T. Vivian, an African American ministerial student and organizer, later said. Carawan introduced “Follow the Drinking Gourd,” and “he gave some background on it and boom, that began to make sense. And little by little, spiritual after spiritual after spiritual began to appear with new words and changes.” Activists like Vivian were initially unsure of the utility of the songs and ambivalent about the message they conveyed. Carawan observed that some Fisk University students were embarrassed to sing and clap in the “rural free swinging style.” The Fisk Jubilee Singers, with which students would have been familiar, sang in a more formal, concert style, without the shouting and stomping that characterized the singing of spirituals in the Lowcountry. But there was also reluctance to sing what were, as Carawan appreciated, “very personal songs about salvation.” Activists, in other words, had to break down the division between the sacred and the secular and connect the songs to the aims of the freedom struggle. As Vivian remembered, “I don’t think we had ever thought of spirituals as movement material.”25

According to Vivian, many movement participants gradually warmed to the idea, removing the spiritual from the past and learning to adapt it to the challenges they faced. Bernice Johnson Reagon, a black SNCC activist and founding member of the Freedom Singers group that toured the country in support of the movement, explained this new approach to the songs. She recalled the first time she sang an old tune—“Over My Head I See Trouble in the Air”—at a mass meeting by exchanging the word “trouble” for the word “freedom.” Reagon then realized that “these songs were mine and I could use them for what I needed.” In Charleston, as we have seen, protesters used the songs for what they needed, too, altering lyrics to suit the context of their local fight against segregation.26

Still, pockets of resistance remained. After their marriage in 1961, Guy and Candie Carawan sponsored several music workshops for SNCC and Southern Christian Leadership Conference activists. Candie, whom Guy met during the 1960 Nashville sit-ins, was not a musician herself. But she was a skilled writer and SNCC organizer who became Guy’s chief collaborator in sharing music with movement participants. In May 1964, the couple organized the Sing for Freedom Festival and Workshop in Atlanta. The Carawans had invited the Georgia-based Sea Island Singers, led by Bessie Jones, to perform at the workshop. They hoped the assembled activists would see the virtues of using the Sea Island Singers’ slave spirituals as they protested segregation in their communities. But Josh Dunson, who covered the event for the folk magazine Broadside, reported that several attendees balked at the material. As Jones and her group shared spirituals and told “old slave stories,” whispers of Uncle Tomism rippled throughout the group. The discussion became heated. One rural woman complained that she was there to learn new songs, not ones she heard at home. Charles Sherrod, who had played a key role in organizing the 1961–62 Albany Movement in Georgia, argued that slave songs had no place at a freedom workshop. Many of the younger activists, Dunson wrote, preferred newer gospel songs and were “ashamed of the ‘down home’ and ‘old time’ music.”27

Bessie Jones shot back. She insisted on the historical and contemporary importance of slave spirituals, making the case that they were “the only place where we could say that we did not like slavery, say it for ourselves to hear.” Rather than viewing the songs as manifestations of degradation, Jones pushed workshop participants to see them as instruments of critique and survival—as the method by which the enslaved safely protested their condition and focused on their ultimate deliverance. Workshop participant Reagon, for her part, told the Carawans that hearing the Sea Island Singers changed her life.28

* * * *

THE CARAWANS BELIEVED so fervently in the importance of preserving and promoting indigenous black music on Johns Island that they moved there in 1963. The couple also continued to nurture appreciation for spirituals beyond Johns Island, and their partnership with Esau Jenkins remained central to their efforts. Working closely with Jenkins, they took the Moving Star Hall Singers on the road to perform at folk festivals in Los Angeles, San Francisco, and Newport, Rhode Island.29

During their time on Johns Island, the Carawans undertook two other major projects to promote Gullah spirituals and culture. First, they partnered with Jenkins to organize a series of folk festivals. Guy hoped the Sea Island Folk Festival for Community Development, inaugurated in the fall of 1963, would promote a revival of spirituals and provide financial support for groups like the Moving Star Hall Singers. Carawan also envisioned the festivals as a way to meet certain “psychological needs” among blacks who had been “conditioned to be ashamed of the way they express themselves.” He wanted, in short, to instill pride in and through slave spirituals. Carawan was careful to position the folk festivals in such a way that local whites might attend, too. He well understood that most white Charlestonians would not go to a “straight political meeting” and publicly insisted that the festivals had “nothing to do with the civil rights question.” Yet he saw the festivals, pitched correctly, as an opportunity to facilitate white contact with, and maybe even interest in, the civil rights movement.30

Among a small group of liberal white Charlestonians, Carawan’s strategy worked. Lindy Cooper saw a newspaper ad about one of the festivals and decided to attend with some friends. “We came out to hear the music, not really expecting what all we got,” she recalled. “We had been the bunch of Southerners who had their heads stuck in the sand about the civil rights situation.” Hearing the music in this particular setting, learning afterward at the Carawans’ home how to shout from the likes of Bessie Jones, and simply being in a racially mixed audience—all of these contributed to a new “awareness” on Cooper’s part. Few white festival goers likely experienced such a racial awakening, but Carawan at least succeeded in getting them there. He estimated that 40 percent of the seven-hundred-person audience at one of the early festivals was white. Other folk artists came, too. Alan Lomax, who attended in 1963, claimed that he saw more good folk singers at the Sea Island Folk Festival than he had at the Newport Folk Festival earlier that summer.31

Guy Carawan and Esau Jenkins inaugurated the Sea Island Folk Festival in the mid-1960s to promote spirituals and broaden the appeal of the civil rights movement.

One group Lomax did not see was the Society for the Preservation of Spirituals. Lomax himself seems to have appreciated the preservation efforts of the SPS. Guy Carawan, by contrast, was critical. He invited the SPS to attend the Sea Island Folk Festivals, but they refused. “They can say they’re interested in this material, but they didn’t want the black people to sing [it] publicly or to be heard,” he later remembered. Only the SPS “could do it.” Whether or not the SPS wanted black spirituals singers to remain silent in public is an open question, but it is clear that the group continued to avoid events that included black spirituals troupes. In 1969, the SPS declined an invitation from the National Folk Festival in Knoxville, Tennessee, because the Moving Star Hall Singers were scheduled to perform.32

The Carawans’ second major endeavor on Johns Island was researching and writing Ain’t You Got a Right to the Tree of Life, an eclectic collection published by Simon and Schuster in 1966. In addition to a preface by Alan Lomax and an introduction written by the Carawans, the book includes oral histories, transcriptions of spirituals, and photographs. The Carawans intended the work as a tribute to black folk culture and their friends on the island, especially to Jenkins. Most of the text consists of native Johns Islanders explaining their customs, especially how they relished “shouting for a better day” at Moving Star Hall, and telling family histories.33

Interspersed throughout the book, the spirituals root these descriptions and reminiscences in the hardships of the slave past. Indeed, black memories of slavery underpin the entire work. The interviewees did not mince words about the peculiar institution, and the Carawans did not attempt to gloss over what they said. For example, Reverend G.C. Brown, pastor at Wesley Methodist, told the couple that his father, a slave in the foothills of South Carolina, left trails of blood in the winter snow before he got his first pair of shoes at age fourteen. Betsy Pinckney remembered that her grandfather had been sold away from her grandmother. “Yes sir! They sell my father’s daddy,” she stated in a frank description of the heartless business of slave trading, “sell him for money.” Pinckney also related a story about how her father’s master knocked him down a flight of stairs for leaving finger marks on shoes he had polished. When the war started, her father “ran off with the Yankees.” A reframing of Lowcountry slave spirituals, Ain’t You Got a Right to the Tree of Life disputed the idealized version of slavery that generations of white Charlestonians had constructed.34

Critics generally praised Ain’t You Got a Right to the Tree of Life. The New York Times congratulated the Carawans for their achievement, while city dailies all over the country, including several in the South, ran positive reviews. The Charleston press was less enthusiastic. Longtime newspaper columnist Jack Leland found the book “delightful and touching,” but he took the Carawans to task for several minor factual mistakes, which, he suggested, cast doubt on the book’s larger critique of white supremacy, past and present. “It is a pity that glaring errors in fact make one wonder about the ‘truth’ the author is touted as telling in a ‘new way,’” Leland concluded.35

Julius Lester, an African American musician and folklorist who was a friend of the Carawans, also criticized the project. “To understand the music of a people,” Lester wrote in Sing Out! magazine, “it is necessary to understand their lives, to intimately know their lives.” When dealing with folk culture, “the most precious raw material available,” the question of who did the interpretation was, for Lester, crucial. “A diamond,” he remarked, “cannot be cut with a nail file.” As Lester saw it, the Carawans, because they were white, were incapable of hewing such a valuable gem.36

By design, Ain’t You Got a Right to the Tree of Life downplayed the central part the couple played in emphasizing the importance of spirituals. And as we have seen, many African Americans were open to the Carawans’ aims. In part as a result of the Carawans’ work, C.T. Vivian, Bernice Johnson Reagon, and the SNCC Freedom Singers, among others, claimed ownership of the spirituals tradition, challenging both black hostility to the genre and the proprietary stance and interpretive bent of white spirituals groups like the SPS. Bill Saunders, who had initially told the Carawans that singing spirituals seemed a waste of time, changed his mind after Ain’t You Got a Right to the Tree of Life was published. “I have gone through many changes since we were last together,” he wrote in a letter to the couple. “Most of the feelings that I had about the Negro music and background have left me, and I feel now that we do have something to feel proud of.”37

But the Carawans could hardly fade into the background altogether given their conviction, which animated Guy in particular, that blacks “were not taking advantage of what their heritage had to offer.” By the time the book was published, the sands beneath the Carawans’ feet had begun to shift. Julius Lester’s Sing Out! review was indicative of the change. Black nationalism and opposition to white involvement in the civil rights movement increasingly affected views of the Carawans’ efforts, as the paternalistic undertones of their work, which had always been present, became too much for some to bear. Summarizing the tenor of the times, Candie later remarked that “you almost had to criticize any white people that were taking a serious interest in black culture.” In fact, in 1965, the year before Ain’t You Got a Right to the Tree of Life appeared, the Carawans left Johns Island for New York, no longer comfortable living among the people whose songs they trea sured.38

* * * *

FORMERLY CONFINED TO black churches or appropriated by white groups like the Society for the Preservation of Spirituals, spirituals singing during the civil rights era resuscitated a memory of slavery that had long existed in the shadows. As spirituals singers of the civil rights era discovered, publicly engaging the history of slavery paid political dividends. Newly empowered African Americans attempted to revive and reshape the public memory of the peculiar institution in other ways—and in other venues—as well. A logical choice was to ensure that Charlestonarea public schools taught black students about slavery. (The prospect of teaching white students the same lessons, it seems, was never raised during these years.)

Negro History Week represented an important annual focal point for studying the black past. In the 1950s, black public schools, such as Burke High School in downtown Charleston—which had been the only public high school for blacks in the city until Avery became public in 1947—and Haut Gap High School on Johns Island, observed Negro History Week annually. Private organizations offered educational programs, too. In the late 1950s, the Charleston chapter of the Links, Inc., a national black women’s organization, sponsored a six-week course in black history at the Coming Street YWCA, an African American branch of the organization, for middle-school students. Eighty-three students completed the class in 1958.39

That year, African American attorney and NAACP counsel John H. Wrighten wrote to the News and Courier to express his gratitude to the Links for this important initiative. “I have been wondering for some time now,” he added, “why Negro history is not being taught in the Negro Schools.” Soon after, Wrighten attempted to persuade the Charleston city school board to include African American history in the curriculum at black schools. An Avery graduate who had unsuccessfully tried to desegregate the College of Charleston and the University of South Carolina Law School (a law school was opened at South Carolina State in Orangeburg as a result of the latter effort), Wrighten submitted the request on behalf of black parent-teacher associations in the city.40

He received a polite but equivocal response to the idea. The school board stated that it had no objections to the teaching of black history in black schools, and it agreed to green light an African American history course when a suitable textbook—one based on “historically authenticated material”—could be identified. When, over a year later, no acceptable book had been found, the school board authorized a committee of black teachers to devise their own study guide to be used in regular history courses. The teachers presented “A Study Outline on the Contributions of the Negro to the United States” at a board meeting in July 1959, but board members objected to the outline, claiming that it contained “generalizations and comments not sufficiently authenticated.” The school board let the matter die and, when Wrighten inquired about the proposal’s status in 1962, the superintendent reported that it was still investigating the issue.41

Meanwhile, black families, churches, and teachers continued to do what they could. By the mid-1960s, they had an unexpected new ally: Old Slave Mart Museum co-owner Judith Wragg Chase. Chase and her sister, Louise Alston Graves, had worked hard to keep the slavery museum afloat after taking over in November 1960. The sisters had difficulty gaining much support from the local community, however. “The early 1960s was a bad time to raise money for black heritage projects,” Chase later explained. “What money was available was all going for civil rights.”42

Graves was the OSMM director and oversaw day-to-day operations, but the museum was really Judith Wragg Chase’s show. A woman of boundless energy, she curated the OSMM’s collection, administered its library and educational outreach program, and led fund-raising initiatives. Like Miriam Wilson before her, Chase believed that the OSMM’s distinctive contributions extended beyond the realms of historic preservation and education. “In spite of marches, sit-ins, and racial tensions,” she wrote in 1970, the OSMM “has not only survived during the past ten years, but has played an important role in promoting inter-racial harmony and has won the respect and admiration of both Blacks and Whites all over the country, as well as in its own community.”43

Although Chase was faithful to what she called Wilson’s “tolerant” approach to slavery, she broke with her predecessor on the relationship between the museum and the civil rights movement. Chase posited the OSMM as a complement, rather than an alternative, to the struggle for integration. A New Deal Democrat and fan of John F. Kennedy, Chase was drawn into the civil rights crusade in the 1960s. One of her early initiatives was to recruit both black and white members to the board of trustees for the Miriam B. Wilson Foundation, the nonprofit she and Graves had created to oversee the OSMM. In 1967, Chase took a public stand against the decision of Charleston’s white YWCA branch to disaffiliate from the national organization because of its integration policy, among other issues. Two years later, she helped to build a new, interracial YWCA of Greater Charleston, serving as its first vice president and on its inaugural board of directors. In recognition of Chase’s commitment to working for equality and justice, a black fraternity awarded her its 1973 outstanding citizenship award.44

Chief among Chase’s civic contributions, according to the fraternity, were her efforts as curator and education director of the OSMM. Miriam Wilson had always hoped to attract black visitors to the slavery museum, but Chase went much further. Early on, she recognized that some African Americans were uncomfortable venturing into the predominantly white neighborhood where the museum was located. So she determined “to take the museum to them.” By the mid-1960s, Chase was regularly lecturing on African American history and culture to black clubs, churches, and PTA groups. Demand for her lectures in the African American community proved so high, in fact, that she began offering a free eight-week course in black history, in part to prepare others to teach similar courses.45

Chase sought to stimulate interest in African American history and culture in local black schools, too. In 1963, she founded an annual art contest for African American high school students and arranged to have the winners’ work put on display at the OSMM. Chase also compiled bibliographies and produced audio and visual resources on African and African American history and culture for black schools and libraries. She reported in 1973 that a slide-rental program she had developed had been embraced by colleges and universities across the United States. Chase’s 1971 study of African and African American art, Afro-American Art and Craft, was similarly popular among college instructors teaching African American art in the early 1970s.46

By that point, the Charleston County School Board, which oversaw instruction in the city and surrounding areas, had finally acknowledged that such topics were worthy of study. In 1970, the board approved a black history syllabus—six years after the desegregation of its schools and more than a decade after John H. Wrighten began lobbying for adding black history to the curriculum. Under the provisions of the federal Ethnic Heritage Studies Act of 1972, the county school board hired Elizabeth Alston, an African American history teacher, as ethnic studies coordinator.47

* * * *

LIKE MOST WHITE southerners, white Charlestonians fought school desegregation tooth and nail. For years, they actively resisted the Brown v. Board of Education decision. In 1960, the Charleston city school board rejected the applications of fifteen black students seeking admission to white schools because their best interests would be “seriously harmed.” Only when some of their parents won a federal lawsuit—and only when the Charleston Movement gave white Charlestonians a glimpse of the disorder that would continue to grip their city if they remained hostile to school desegregation—did officials relent. On September 3, 1963, eleven African American students began the new academic year at formerly all-white schools. Three bomb threats were phoned in that day to Rivers High School, where Millicent Brown—whose grade school field trips to the Old Slave Mart Museum had been such a disappointment—had enrolled. In subsequent school years, white Charlestonians took advantage of a statewide program that provided tuition dollars to attend private schools. By 1967, black students represented more than 86 percent of students in Charleston city schools.48

African American students in desegregated schools began advocating for the importance of studying the black past. Their increasing assertiveness tracked with national developments within the Black Power movement as well as within the black student movement to which it helped give rise. Forged at historically black colleges before spreading to formerly all-white institutions, the student movement attacked, among other things, curricula too beholden to white norms and narratives. In Charleston, black students’ concerns were met with genuine hostility, even violence, especially in those suburban schools that remained mostly white. Just across the Ashley River in Charleston’s western suburbs—where increasing numbers of middle-class African American families moved from the peninsula in the 1970s—black students at St. Andrews High School called for an improvement to what they dismissively called their “Black history supplement.” It was “one big joke,” they said in early 1972, as the white teachers “don’t know and don’t care” about the subject and sometimes called on black students to teach it themselves.49

Campus traditions at athletic events exacerbated this neglect of black history. At St. Andrews, students waved the Confederate battle flag and sang “Dixie,” practices black students loathed. When the school refused to address their concerns, they boycotted classes. Their white classmates responded by flying Confederate flags emblazoned with the letters “KKK.” At James Island High School, the observance of Negro History Week in the winter of 1972 led to a well-orchestrated attack on black students. As they arrived at school on the morning of February 15, the white students, some armed with pistols, threw rocks and bricks as their parents looked on.50

Black students at Charleston colleges fought similar battles. Desegregated in 1966, the Citadel struggled to respond to its black students’ demands to diversify its curriculum and confront its complicated history. The defense of slavery and the Civil War, after all, were central to the college’s identity. Founded as a response to the Vesey conspiracy, the school had long bragged that its cadets had fired the opening salvo of the conflict when they shot at a Union supply ship headed to Fort Sumter in January 1861, three months before General P.G.T. Beauregard’s fateful assault on the fort. “Dixie” was the unofficial fight song of the college, and the Confederate battle flag, waved at athletic competitions, held deep symbolic meaning for students and alumni.51

The Brigadier, the student newspaper, explored the racial climate on campus in several 1970 articles. As the spring semester came to a close, the editors raised the question of whether a black history course, or an entire black studies program, should be created. Its willingness to entertain the idea contrasted with that of the News and Courier editorial board, which in 1969 deemed black studies the kind of revisionist history favored by totalitarian regimes like Soviet Russia and Nazi Germany. The Brigadier, by contrast, suggested that such a program might “eradicate inter-racial misunderstandings which thrive on prejudicial ignorance” and invited campus members to weigh in on the issue. African American cadets supported the proposal, as they felt current faculty soft-pedaled subjects like slavery. One black cadet remembered how difficult it had been for him to challenge a history professor’s benign interpretation of the institution, especially because he was the only African American student in the class.52

African American cadets at the newly desegregated Citadel objected to their fellow students’ flying the Confederate flag at football games.

The following academic year, African American cadets went on the offensive, moving beyond the call for black studies. Members of the newly founded Afro-American Studies Club (AASC) took aim at the college’s traditions, shining a bright light on how the school’s particular memory of slavery informed campus culture. After asking, to no avail, that the administration forbid the flying of the Confederate battle flag at football games, the AASC decided in the fall of 1971 to counter this symbol with its own. When the Citadel put its first points on the scoreboard at the Illinois State football game, white cadets, per usual, waved the battle flag. Black cadets responded by raising an “anti-flag flag” they had made; it showed a black fist crushing a Confederate battle flag.53

This incident pushed Citadel administrators to ban the use of the flag at games, but they failed to fully understand black cadets’ criticisms of college traditions. In a report issued in 1972, Citadel officials summarized the most common grievances of the typical black cadet: racist insults went unpunished, American history courses ignored black contributions to the past, and the “Confederate Legend” dominated campus culture. Concluding that it was impossible to determine the legitimacy of these complaints, administrators offered several observations to guide future campus policies. The Confederate Legend, most importantly, was “an integral part of The Citadel’s heritage.” Conceding that the battle flag was “inappropriate for a football standard,” the report nevertheless insisted that “the school should explain that the Confederate States of America stood for more than slavery and that the Confederate battle flag is not the official emblem of white supremacy.” No cadet, white or black, should reject the heritage of his college by presuming to judge the past, it insisted. Indeed, Citadel officials blamed the discord on campus on this very habit: “The current preoccupation with the influence of slavery is responsible for the extreme unpopularity of anything associated with the Confederacy.” The report endorsed the request that history professors examine the role of African Americans in the past, but only on one condition—that they do so “without distorting their subject.”54

Many white Citadel students responded more angrily to their black classmates’ grievances. After the 1971 Illinois State game, a group of white cadets vandalized the AASC president’s dorm room. To make their point, they suspended a noose from the ceiling, dangling a doll in the loop. The flag ban elicited a slate of articles in and letters to the Brigadier, with most writers condemning the administration’s decision as a violation of a sacred campus tradition.55

Only a handful of white cadets publicly sympathized with the black cadets’ position on campus symbols. Preston Mitchell, class of 1974, wrote to the Brigadier after a basketball game against Midlands Tech to criticize what he saw as deliberately provocative behavior on the part of the Citadel Regimental Band. The band continually played “Dixie” during the game, Mitchell observed. Each time, the tempo got faster, and the cadets whistled louder and stomped their feet harder. The band seemed intent on harassing the almost exclusively black Midlands basketball players and cheerleaders. Mitchell pleaded with Citadel students to see that from a black person’s perspective “Dixie” represented white supremacy and the KKK. Mitchell did not believe that the playing of the song should be dropped as a Citadel tradition, but he felt it needed to be kept “in its proper perspective.” A plea to silence “Dixie” would likely have been ignored anyway. The administration’s halfhearted commitment to placating black students was fading, and by the end of the decade, cadets were again waving the Confederate battle flag at athletic events.56

* * * *

THE LATE 1960S and early 1970s marked a turning point in the political fortunes of black Charlestonians. The freedom struggle had ebbed since the 1963 Charleston Movement, but in 1969 picket lines and marches once again rattled the city as a new fight over labor rights erupted. Tensions over low pay and discriminatory employment policies had been simmering for several years between the Medical College of South Carolina Hospital and the Charleston County Hospital, on the one hand, and their predominantly black female workers, on the other. On March 20, after administrators fired twelve union leaders from the Medical College hospital, over four hundred employees of both hospitals went on strike. Thousands of local protesters, as well as the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), rallied to the workers’ cause, while the hospitals dug in their heels. It was, according to the New York Times, “the country’s tensest civil rights struggle.” In late April, the South Carolina governor ordered five thousand National Guard troops to patrol Charleston and announced a dusk-to-dawn curfew.57

Hospital workers drew parallels between their current condition and antebellum slavery. At a protest held in front of the Old Slave Mart Museum, one picketer held a sign that read, “In Memory of the Old Slave Tradition, Consult Dr. McCord,” a reference to Dr. William McCord, the president of the Medical College of South Carolina who refused to meet with the workers’ union and portrayed the strikers as children. The specter of Denmark Vesey, in particular, hung over the hundred-day walkout, his spirit seeming to animate the hospital workers’ own insurrection. As they marched through the streets, strikers and their allies shouted “Remember Denmark Vesey!”—the same cry that Frederick Douglass had employed to recruit African American soldiers during the Civil War. In early May, SCLC president Ralph Abernathy told a crowd of three thousand that he planned to preach against economic injustice at the “hanging tree” on Ashley Avenue, where local myth held that Vesey had been executed. Even whites thought of the famous rebel. To the News and Courier—which, unsurprisingly, had little patience with the strikers—the “eerie silence” of the nightly curfew called to mind the curfew imposed in the wake of Vesey’s thwarted slave rebellion. Alice Cabaniss, a liberal Charleston poet, captured the tense events of the summer in verse, writing, “Merchants lounge in doorways / cursing ease, grouping angrily / . . . patrolling windows, / counting guardsmen going by. / . . . Denmark Vesey smiles / with plea sure from another century.”58

Police arrested nine hundred demonstrators before a settlement, which produced modest victories for hospital workers, was reached in the summer of 1969. The resolution was far from perfect, but the mass mobilization was a watershed, creating a larger space for working-class black Charlestonians within the local civil rights movement. It was a call to arms for a broad-based coalition of black activists who drew on nonviolent direct action as well as the militancy of Black Power. Among these were Mary Moultrie, the union president, Bill Saunders, the Johns Island activist, and Robert Ford, a young SCLC organizer.59

Two years later, James J. French translated this growing power into a new newspaper, the Chronicle, that spoke to the local black community. The Chronicle served as a vehicle to galvanize support of black political candidates and to expose ongoing problems of discrimination, though French did make room for a variety of voices, including a conservative white columnist. Significantly, Chronicle stories on contemporary issues were intertwined with article after article on black history, which focused overwhelmingly on slavery and resistance to it.

The Chronicle’s discussions of slavery supported a vision of activism indebted to Black Power. The first of a four-part series in the fall of 1972 titled “Revolt Against Slavery,” for example, noted that very few history books concentrated on slavery’s inhumanity, but fewer still detailed those who fought the institution. There were bondpeople, however, “who fought back. They fought back against enormous odds and they often lost, but they did not passively accept their chains. They resisted—sometimes to the death.” The interpretation of slavery that permeated the pages of the Chronicle was certainly unvarnished, as were the characterizations of how slaves had responded. “The stories of Nat Turner, Denmark Vesey, and Toussaint L’Ouverture—men who stood up in the midst of the overwhelming machinery of slavery and fought for their freedom,” the paper stated, “their heritage lives today with young Black militants like Stokely Carmichael, H. Rap Brown, Eldridge Cleaver, and Ron Karenga.” The newspaper hoped its memory of slavery would provide black Charlestonians with a usable past to inspire their fight against injustice.60

For many local African Americans, in fact, Denmark Vesey—the city’s original black militant—represented the most potent symbol of this usable past, his example of resistance waiting to be harnessed for the contemporary political moment. Striking hospital workers, of course, had already invoked Vesey as inspiration during their walkout in 1969. In the spring of 1975, several African American residents suggested that it was time for Vesey to be more widely known. Charleston, they argued, should somehow memorialize the insurrectionist. The campaign began when Reverend Matthew D. McCollom, president of the state NAACP, and civil rights attorney Arthur C. McFarland, one of nine students who in 1964 had desegregated a local Catholic high school, suggested renaming a city school after Vesey. McFarland argued that renaming several predominantly black schools—Burke High School, for example, would become Septima Clark High School; Charleston High School would become Robert Smalls High School; and Columbus Street Elementary would become Denmark Vesey Elementary School—would give black children “a sense of history—of how Black people began as slaves in this city and country and how we have steadily achieved despite overwhelming discrimination and oppression.”61

McCollom and McFarland’s effort inspired other ideas for memorializing Vesey. In October 1975, the city council voted to rename the Municipal Auditorium, completed in 1968, in honor of Mayor J. Palmer Gaillard Jr., whose administration had overseen construction of the facility and who had recently announced his retirement from office. Robert Ford, a former SCLC staffer and hospital strike organizer now vying for a seat on the city council, countered that the auditorium should be named for Vesey instead. Ford framed his proposal as a way for the city to render black citizens just compensation. In constructing the massive structure, the Gaillard administration had razed entire blocks, forcing a number of black businesses and churches to relocate to other parts of the city and displacing seven hundred poor, mostly black Charlestonians from their homes.62

Finally, in December, several African American citizens urged the city to erect a statue of Vesey. One of these was Reverend Frederick Douglass Dawson, a minister at Calvary Baptist Church, an NAACP leader, and one of the parents who had successfully sued to desegregate Charleston’s public schools. Dawson envisioned a Vesey statue, situated in front of the newly rechristened Gaillard Municipal Auditorium, as a natural complement to another project he had in mind: renaming King Street in honor of Martin Luther King Jr. Dawson made his case for both before the city council. “I think it’s about time council members and citizens of Charleston show some respect for our Black heroes and heritage,” he proclaimed. City and state leaders had not just ignored men like Vesey. They had fashioned a commemorative landscape that was an affront to black citizens. As he observed, “They have statues of slave holder John Calhoun in the downtown area and Ben Tillman stands on the lawn of the State House in Columbia.” Putting up a statue of Vesey would represent a step toward rectifying this “intolerable situation.” Bobby Isaac, an African American reporter for the News and Courier, threw his support behind the statue idea, too, arguing that a public square or park would be an ideal site. “As a Black Charleston resident,” he wrote, “I feel personally slighted because of the gross absence of any significant Black historical marker in this city, which has for so long prided itself for its rich and colorful history.”63

As Isaac pointed out, Vesey’s “invisible landmarks,” such as Emanuel A.M.E. Church and the Citadel, “today quietly haunt the city he had plotted to take.” Isaac, Dawson, Ford, McFarland, McCollom, and others felt it was time to give Vesey a visible landmark—one that would finally acknowledge how the memory of his conspiracy shaped, and continued to shape, life in Charleston. Initial responses to their proposals were not encouraging. The school board did not adopt the recommendation to rename black schools. The city council, understandably, did not entertain the request to rename the auditorium for the second time in as many months. Council members referred the other suggestions they received to committee. Reactions by and in the white press were cool. The Evening Post chided African Americans for trying to turn Vesey into a hero, while a letter writer to the News and Courier worried that “cluttering up” the area around Gaillard Municipal Auditorium with a statue to a former slave would hinder downtown revitalization. Tom Hamrick, a conservative white journalist who wrote a weekly column in the Chronicle, was the most hostile critic, arguing that Vesey was “a would-be killer who wanted to convert Charleston into a blood inferno.” Hamrick speculated that no one could have been less popular among white Charlestonians than Vesey, not even Adolf Hitler.64

Hamrick may well have been right, but as of December 9, 1975, the Vesey memorializers had a distinct advantage. Municipal elections held that day transformed Charleston, ushering in a new political order. This new order was in many ways the product of the 1969 hospital strike, which had increased black voter registration among the working class and elevated a cohort of younger, more militant black leaders who challenged the conservative black establishment and its accommodation of local white Democrats. A Justice Department ruling helped, too. In February 1975, federal officials had ordered the city to switch from at-large to single-member districts, which promised to improve black representation on the city council.65

That promise bore fruit. The December 9 elections produced a twelve-member council, evenly divided among white and black members, one of whom was Robert Ford. Along with Bill Saunders, Ford typified the new breed of black activist in the city. Born in New Orleans, Ford had relocated to Charleston in 1969 to help with the hospital workers strike. Through this grassroots activism, Ford hoped to take power away from the “soft-speaking, Uncle Tom Folks.” To that end, he ran for city council in the 1975 municipal elections, and in the mayoral contest he backed George Fuller, an African American candidate who ran as an independent, rather than the white Demo cratic nominee, Joseph “Joe” P. Riley Jr.66

Fuller lost the mayor’s race to Riley, a thirty-two-year-old racial progressive. A local boy from an Irish Catholic family who grew up south of Broad, Riley had graduated from the Citadel, earned a law degree from the University of South Carolina, and been elected to the General Assembly in 1968. Despite his conservative upbringing, Riley broke ranks on race and helped to forge a new Democratic Party in the process. Riley came on the political scene amid a massive political realignment in the United States, as southern opponents of integration, led by South Carolina’s Senator Strom Thurmond, bolted the Democratic fold for the Republican Party in the 1960s and 1970s. Gradually, the term “Solid South” took on a new meaning, with Republicans holding sway across the region by the turn of the century. Cities like Charleston bucked this trend, however, since its sizable population of newly enfranchised black voters flocked to the Demo crats.67

After the hospital strike and the narrow reelection victory of Mayor Gaillard in 1971, Riley had pleaded with his fellow Democrat to reach out to black Charlestonians and represent their needs. Three years later, he joined with black representative and SCLC member Robert Woods to introduce a bill in the General Assembly to create a statewide Martin Luther King Jr. Day. Riley may not have been a civil rights activist, but his commitment to the welfare of black citizens was genuine, in addition to being politically savvy. In the 1975 mayoral contest, Riley earned the votes of both wealthy white Charlestonians and recently empowered African Americans, Robert Ford notwithstanding. Riley and his new interracial coalition would dominate Charleston politics for the next forty years.68

Emboldened by the historic election, the new mayor and the city council still tread carefully when it came to the proposal to memorialize Vesey. In fact, in early 1976 Mayor Riley suggested commissioning a portrait of Martin Luther King Jr. to hang in City Hall instead. But black activists responded that honoring a Charleston or South Carolina native was more appropriate, and that Vesey had already emerged as the preferred choice of any commemorative effort. Riley agreed. On Robert Ford’s recommendation, the council commissioned a portrait of Vesey to hang inside the cavernous lobby of Gaillard Municipal Auditorium.69

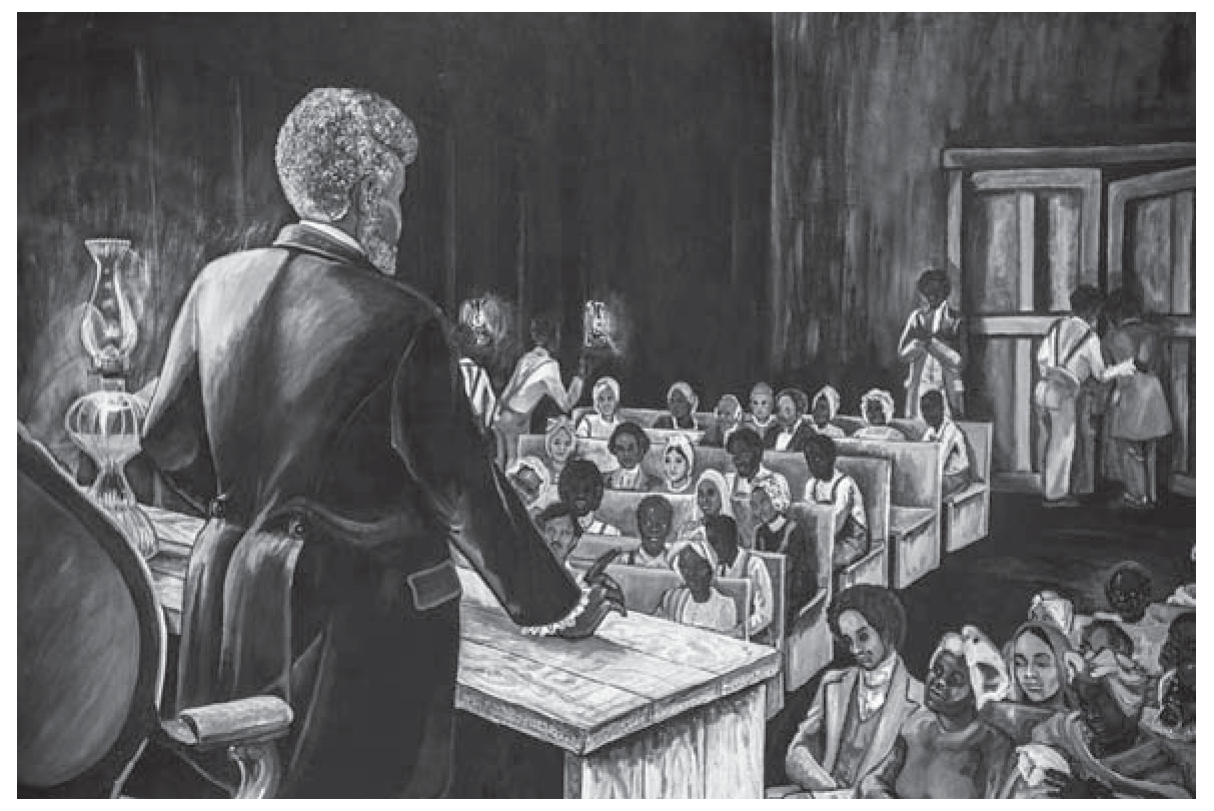

Painted by Dorothy B. Wright, an art teacher at C.A. Brown High School, the portrait showed Vesey from behind, preaching to congregants of the African Church. Wright’s composition nodded to his role as a minister while also providing a convenient way around the fact that there are no known images of his face. The city paid $175 for the work and unveiled it on August 9, 1976, at a ceremony attended by 250 people. Various local dignitaries spoke at the event, including Reverend Frank M. Reid Jr., an A.M.E. bishop, and Mayor Riley, who hailed the occasion as proof that his administration would ensure that “parts of history heretofore forgotten are remembered.”70

But if Councilman Ford, Mayor Riley, and other proponents of the portrait thought their tribute, tucked away inside the auditorium, would not incite controversy, they miscalculated. Many white Charlestonians were outraged that an image of a man they considered a criminal now hung in a civic space, even if it was located behind closed doors rather than in a public park. Shirley J. Holcombe, a Republican running for the state House of Representatives, summarized how many of her constituents felt in language that echoed Tom Hamrick. Holcombe declared, “If Vesey qualifies for such an honor, we should also hang the portraits of Hitler, Attila the Hun, Herod the murderer of babies, and the PLO murderers of the Israeli athletes at Munich.”71

Denmark Vesey Talking to His People, by Dorothy B. Wright. Black Charlestonians memorialized Vesey with this painting, hung in Gaillard Municipal Auditorium in 1976. About five weeks after it was installed, the tribute was stolen.

The primary problem was Vesey’s alleged methods. News and Courier columnist Frank Gilbreth Jr., better known by his pen name Ashley Cooper, admitted that slavery may have been immoral, but it was the law of the land. An insurrection that would have resulted in the slaughter of white Charlestonians, as he and other critics contended, was simply inexcusable. The evolutionary change in race relations that had characterized the twentieth century, the Evening Post editorialized, was far preferable to such a violent overthrow, which was doomed to futility anyhow. In recent years, Ashley Cooper claimed, southern whites had “bent over backwards to purge themselves of prejudices and to change their ways of life to accommodate the rights and feelings of blacks.” Given their change of heart, they would never propose a project that was as insulting to the black community as the Vesey portrait was to the white. They would not, for example, contend that statues of Robert E. Lee or Jefferson Davis be installed in Hampton Park, a popular gathering spot for black Charlestonians since its desegregation a decade earlier.72

Cooper’s estimation of how willingly whites had changed their racial views was generous, to put it mildly, but his remark about Hampton Park reveals an important truth: for many white Charlestonians, the Vesey painting hit close to home. Gaillard Municipal Auditorium, after all, was mostly an elite white civic domain. White patrons would now mingle under a portrait of Vesey before and after every performance they attended. But opponents did not so much object to the location of the painting as to its subject, wondering why Ford and his ilk could not find a better candidate for commemoration. There were plenty of distinguished black men and women from Charleston, they contended. Choosing a man of “evil” made no sense.73

Portrait proponents vigorously countered the detractors. To Robert Ford and Reverend Frank M. Reid Jr., who delivered the keynote at the dedication ceremony, Vesey’s plan to kill whites so that he and his co-conspirators could set sail for Haiti did not make him a racist, as whites charged, nor was he “a wild-eyed monster.” He was a Moses, a freedom fighter sent by God to liberate his people. Vesey defenders also pointed out that slaves had no other alternative but violent rebellion. If men like Vesey and Robert Smalls “did not struggle for what is morally and legally right, then there would be no thirteen Blacks in the S. C. House of Representatives, or Blacks on the school board,” declared the Chronicle. To think that “natural events” and white benevolence would have ended slavery was “hogwash.” For centuries, Americans had committed acts of violence and laid down their lives for causes they held dear. Vesey was no different.74

White Charlestonians, Vesey defenders noted, knew this well. They had installed statues and named parks in honor of Revolutionary and Confederate fighters—most of whom had been slaveholders—all over the city. How ridiculous it was, the Chronicle declared, for the pot to now be calling the kettle black. To Bill Saunders, this hypocrisy was galling. He bristled at the fact that whites wanted to tell African Americans who to celebrate when blacks had walked by these tributes to white oppressors for decades, largely keeping their opinions to themselves.75

None of those who emphasized the inconsistency of white Charlestonians regarding commemoration went so far as to argue that white memorials should be removed. Rather, supporters of the Vesey painting wanted city spaces to be more representative and inclusive. Whites could honor their heroes; African Americans could celebrate theirs.

* * * *

THE WAR OF words that played out after the Vesey painting dedication did not mark the end of the story. Sometime in the late afternoon or evening of Friday, September 17, 1976, about five weeks after it had been installed, the portrait was stolen. The thief or thieves ripped the painting off the wall, leaving four large holes behind. Charlestonians learned of the incident in a brief article relegated to the bottom of Section C of the Sunday News and Courier. A $200 reward was offered for the painting’s return. Mayor Riley insisted that a replacement would be commissioned if it were not given back. Black activists chided the white press, faulting it for inciting the robbery. As they pointed out, moreover, white newspapers had devoted copious space to attacking Vesey during the previous months but had buried the story detailing the portrait’s theft. Sunday night, an anonymous caller informed the News and Courier that the painting had been returned to Gaillard. A reporter followed up on the tip and found it lying against an auditorium door. Although the police took fingerprints from the portrait and investigated the crime, they never made an arrest.76

The city reinstalled the Vesey painting in Gaillard Municipal Auditorium, hanging it higher up the wall to stave off another theft. But it never replaced the plaque that had accompanied the original painting, which had also gone missing. This plaque paid honor to Denmark Vesey, calling him a “lover of freedom” and “enemy of oppression” who “planned a major slave revolt.” In its absence, Gaillard visitors were left to their own devices to figure out the identity and significance of the black preacher depicted in Wright’s portrait.77

This incident simultaneously highlighted what had changed in Charleston over the last two decades and what remained the same. The city now had a liberal white mayor who not only owed his election to the black community but was also committed enough to memorializing Charleston’s African American history that he made sure a portrait of Denmark Vesey would hang in its most prominent auditorium. For this and other acts of racial reconciliation, in fact, Riley earned the derisive nickname “Little Black Joe.” Yet the dogged fight conservative whites launched against this single commemorative gesture—symbolically significant as it was—laid bare the deep divisions over the public memory of slavery that persisted throughout the civil rights era and beyond.78