BY THE TIME OF THE VESEY PORTRAIT CONTROVERSY and theft, Charleston’s powerful cadre of preservationists and tourism boosters had stepped up their efforts to remove most traces of slavery from the city. This was a campaign that dated back to World War II, when inscribing white memory into the built landscape became fully institutionalized. In 1941, a committee associated with the Carolina Art Association conducted an architectural survey of Charleston, the first inventory of buildings in the city and one of the first studies of its kind in the nation. The committee tapped Helen Gardner McCormack, a Charlestonian serving as the director of the Valentine Museum in Richmond, to conduct the survey. Beginning in January 1941, McCormack crisscrossed the peninsula, on foot and by car, and by the end of the year she had identified over eleven hundred private dwellings, public buildings, churches, and other sites deemed worthy of preservation. In December 1944, the survey results were published in book form. This Is Charleston: A Survey of the Architectural Heritage of a Unique American City included photographs of 572 of the structures identified as important.1

The survey and book did not just catalogue the buildings worthy of preservation, as these structures represented so much more. Frederick Law Olmsted Jr., who served as an adviser for the project, came to appreciate this fact during a trip to Charleston. “Whatever else the Committee is concerned with it is very centrally concerned with some intangible values peculiar to Charleston,” observed the son of the famous landscape architect. “They are . . . characteristic of certain physical aspects of Charleston and definitely associated with certain kinds of old physical objects and conditions.” As it set out to map the cityscape, the committee mapped a landscape of memory that embodied its peculiar values—a landscape of memory that made those values tangible. Old physical objects encapsulated elite Charlestonians’ sense of themselves, past and present.2

Indeed, the survey methodology was rooted almost entirely in the personal memories and assessments of the individuals who constituted the committee. Helen Gardner McCormack relied on Albert Simons—an architect, head of the city’s Board of Architectural Review, and SPS member—who gave her his notes and files, as well as on watercolorist Alice Ravenel Huger Smith, who led her on private tours. Alice “took her car and chauffeur,” McCormack explained, “and we drove around and she pointed out things that she remembered that she thought were important. That was extremely helpful.” Alice’s own sense of what was historically significant had been shaped by her paternal grandmother and her father. Eliza C.M. Huger Smith had regaled her granddaughter with the exploits of Charlestonians dating back to the colonial period. Alice’s father, Daniel, an author, antiquarian, and Civil War veteran, had led her as a child on walking tours of the city and area plantations in his search for sites associated with prominent Charlestonians. “We would visit hero after hero,” she said. “We would meet famous soldiers and sailors, lawyers, judges, captains of industry and delightful old ladies, and many young ones, too, for he had so many stories to tell us that history became real.” Alice valued this “historical training,” as she called it, as did McCormack.3

This Is Charleston failed to acknowledge that enslaved laborers had constructed or lived and worked in the buildings it listed. The book included photographs of just two sites that explicitly evoked the history of slavery, though the link was not made clear. Slave quarters at 45 Queen Street were described using the popular euphemism “servants’ quarters.” The Old Slave Mart Museum, which Miriam Wilson had opened as a museum three years before the architectural survey, was labeled simply “6 Chalmers Street. Ante Bellum. Notable.”4

This Is Charleston became the go-to guide for educated visitors as well as for preservationists and municipal officials. But that was not all. Several committee members decided that Charleston needed a new preservation society, establishing the Historic Charleston Foundation (HCF) in 1947. The HCF bought historic properties, eventually pioneering a revolving fund that was regularly replenished to finance future purchases. The properties, in turn, were rehabilitated for modern use.5

One of the HCF’s most important and long-lasting projects underwrote this scheme: a springtime series of private home tours inaugurated in 1948 that continues to this day (under the name Festival of Houses and Gardens). For out-of-towners, especially, the tours offered an exciting glimpse into the private, mysterious domains of wealthy Charlestonians, something promoters emphasized. Home-tour patrons could be forgiven for assuming that Charleston had been populated mainly by the prosperous families of merchants and planters in the colonial and antebellum eras. Even ghosts, several said to still haunt grand old homes, occupied a more conspicuous place in the foundation’s tour narratives than “servants.”6

The historical vision of these preservationists lived on in other ways as well, informing Charleston’s first attempt to improve the tourist experience in the postwar years. At the request of the city, the Historical Commission of Charleston (HCC) designed a tour guide licensing program in the early 1950s so that guides would possess “authentic, factual and interesting historical data.” The program, a series of classes at a local vocational college that culminated in an exam, operated under the supervision of HCC secretary Mary A. Sparkman and Helen Gardner McCormack. Sparkman possessed a formidable knowledge of local history, having served as the secretary of the HCC since its founding in 1933. During her tenure in office, she had personally conducted much of the research necessary for the commission’s projects—research that became the basis of the information that prospective guides had to master to obtain licenses. Helen Gardner McCormack was also a logical choice. As head researcher for the 1941 architectural survey, few people could have known more about the streets of Charleston.7

Black history largely lay beyond the scope of this licensing program. The 1954 exam, for instance, contained sixty questions, but just one that tested knowledge of black life in the city: “The most modern school for negroes in the city is ________ on _________ Street.” This query, of course, reflected what guides were taught. Totaling more than 150 pages, an early version of the study manual for prospective tour guides devoted only a handful of pages to black sites, black history, and black culture. (The city’s flowers, by contrast, merited twelve.) An entry for “Negroes,” located in the “miscellaneous data” section at the end of the manual, informed guides that they needed to know “something about what has been done and is being done for the negroes in the city”—thus the question about the modern school built for black students. The HCC’s tour-guide material from these years did include more information about the Old Slave Mart and the city’s slave trade than did most Charleston tour guidebooks from the same period. But, as we saw in chapter 8, Sparkman and her collaborators attempted to distance Charleston from slave trading by stating that the building had no official, municipal standing.8

Sparkman and McCormack’s material was updated in 1973 by Marguerite C. Steedman, a United Daughters of the Confederacy member hired by the city council to teach a revised instructional course for tour guides. Steedman’s revisions were not interpretive in nature, as she was not sympathetic to those calling for a reassessment of the southern past in the wake of the civil rights movement. In 1979, for example, Steedman blamed a recent dustup over the flying of the Confederate flag at the statehouse in Columbia on new, revised textbooks “written and published elsewhere,” as well as on the popularity of the television miniseries Roots, which she called “a piece of warmed-over Abolitionist propaganda if there ever was one.” Steedman lamented that too many southerners could not distinguish between such propaganda and true history.9

The longevity and influence of the city’s licensing program speak to a larger point. To a remarkable degree, the consolidation of white memory after World War II rested on an expanded, more formalized tourism industry. This more formalized tourism industry, in turn, rested on the work—and recollections—of a handful of leading white Charlestonians. Tourists who hired a licensed guide to lead them through the historic district; those who ventured out on their own with a copy of This Is Charleston in hand; those who patronized the annual home-tours festival—all of these visitors navigated a landscape constructed out of a chain of elite personal remembrances.

Artist Elizabeth O’Neill Verner, who, despite her modest background, collaborated in forging this landscape with her romanticized drawings of the city, effectively explained this peculiar dynamic. As Verner wrote in 1941, the year the architectural survey was conducted, “I think people have time to remember better in Charleston than in most places. Perhaps it is easier to remember here where the generations are all known to each other and linked up, for by the time one has reached the half-century mark, a Charlestonian is likely to have known five generations of any family.” And what that Charlestonian learned from those earlier generations mattered. As it passed from Daniel Elliott Huger Smith to Alice Ravenel Huger Smith to Helen Gardner McCormack to tour guides to tourists, individual memory became public memory.10

* * * *

AN INFAMOUS INCIDENT in 1961—sparked by the highest-profile tourist event in the city since the 1901–2 Exposition—captured Charleston’s stubborn commitment to this narrow approach to the past. That April, one hundred years after the Confederacy launched its war to save slavery at Fort Sumter, the city staged an elaborate commemoration of the fateful assault. Fifty years earlier, Charleston had let the Fort Sumter semi-centennial pass without public ceremony, an accommodation to sectional reconciliation and, perhaps, fiscal challenges. By 1961, many locals believed that a Civil War anniversary commemoration was not only fitting but also potentially profitable. The Fort Sumter National Monument, which had been operated by the National Park Service since 1948, had already become an established tourist stop, attracting more than fifty thousand visitors in 1960. With national publications predicting that the centennial could draw twenty million people to Civil War sites and spectacles, Charleston boosters unleashed an unprecedented publicity campaign. “Even if it lost the war,” ventured the News and Courier, “the South is bound to emerge victorious from the centennial, in terms of tourist dollars, at least.”11

Yet Charleston’s Jim Crow policies threatened to jeopardize those tourist dollars. The Civil War Centennial Commission (CWCC), a federal body created by the Eisenhower administration to coordinate commemorative activities, had decided to hold its fourth national assembly in Charleston during the Fort Sumter anniversary in April. The site selected to host the meeting was the segregated Francis Marion Hotel, a choice that did not sit well with the New Jersey delegation, which included African American Madaline Williams. Its protests, however, proved unsuccessful. CWCC executive director Karl Betts insisted that the matter was outside his commission’s jurisdiction. After consulting with the Francis Marion, Mayor J. Palmer Gaillard Jr. reported that neither Williams nor any other African American delegate would be permitted to stay in or to dine at the hotel, a widely publicized stand that earned Gaillard letters of praise from across the South.12

In response to the Jim Crow accommodations, centennial delegations from four states—New Jersey, New York, Illinois, and California—proposed boycotting the assembly. With the controversy grabbing national headlines, President John F. Kennedy intervened. On March 14, he urged the CWCC to ensure that all guests attending the meeting were treated equally. By the end of the month, Kennedy aides and Emory University historian Bell Wiley, a self-described southern liberal who sat on the CWCC executive committee, had forged a compromise: the national assembly would be moved from the segregated Francis Marion in downtown Charleston to an integrated U.S. naval station outside the city.13

Local whites took the news in stride. The chairman of South Carolina’s state centennial commission announced that regardless of where the national meeting was held, his group would neither alter its commemorative program nor “participate in any integrated social functions.” Charleston newspapers ran articles highlighting the naval station’s austere accommodations, how few delegates had signed up to stay there, and the fact that the station’s remote location would prevent its occupants from attending the important commemorative events downtown.14

Despite the national uproar, Charleston’s Fort Sumter commemoration went on as planned. White fears about civil rights activists picketing at the Francis Marion failed to materialize, though the NAACP did stage a late-night protest rally at Emanuel A.M.E. Church, which was attended by Madaline Williams and a white New Jersey delegate. At that April 11 gathering, a 1,200-person crowd endorsed a statement that denounced any glorification of the Confederacy, “for it was founded on the principle of slavery.” But their sentiments were drowned out by the city’s Lost Cause party.15

Visitors packed area hotels. Local entertainers, including the Society for the Preservation of Spirituals and Gullah raconteur Dick Reeves, offered special performances for southern delegations, which gathered for separate, segregated meetings at the Fort Sumter and Francis Marion hotels. Not even heavy rains and a tornado that touched down in the area on April 12—the anniversary of the first shot fired at Fort Sumter—could dampen the city’s spirits. That afternoon, a crowd of 65,000 turned out for an enormous parade that snaked through the center of the city. Confederate flags and hats were everywhere. In the evening, tens of thousands watched a reenactment of the bombardment of Fort Sumter. On the Battery, “Confederate gentlemen and belles danced and whooped it up” to “Dixie” and “Tara’s Theme” from Gone with the Wind.16

Unsurprisingly, Charleston’s Fort Sumter centennial made little room for slavery. For six nights, the Citadel football stadium hosted a historical pageant that dramatized the city’s past. “The Charleston Story” featured a cast of five hundred, including more than one hundred principals who depicted both real and historical figures, such as King Charles II and P.G.T. Beauregard, as well as symbolic types, including a plantation owner, a pirate’s ransom victim, and a war bond saleswoman. Only a handful of characters represented Charleston’s black residents. The pageant did not address slavery, though it made explicit reference to other forms of bound labor, such as indentured servitude. Slavery did not merit much comment at other centennial events either, with the exception of the standard Lost Cause talking points. During a performance at the Fort Sumter Hotel, Dick Reeves told about two hundred delegates that it was an appropriate moment “for the people of the South to remember the loyalty of many Negroes during the Civil War.”17

Viewed through a national lens, the Fort Sumter commemoration promised to lay bare sectional fault lines over how the nation remembered the Civil War—fault lines that seemed far more potent in light of emerging civil rights challenges to Jim Crow. The negative publicity garnered by the Charleston controversy, in fact, led Congress to cut CWCC funding.18

Locally, however, the centennial taught a different lesson. White Charlestonians regarded the Fort Sumter commemoration as “a great success,” in Mayor Gaillard’s words. Asked by a News and Courier reporter if the ruckus over Williams had disturbed the festivities, he left little room for doubt. “No sir,” Gaillard replied. “As far as I personally am concerned, it didn’t even exist.” Charleston tourism operators were similarly upbeat about the positive impact of the centennial. In October, the superintendent of Fort Sumter reported that 60,492 people had visited the site in the first nine months of 1961—almost 9,000 more than the total number of visitors in all of 1960.19

Change came slowly to Charleston’s historical tourism industry. Well into the 1970s, plantation owners marketed their sites as enchanting gardens guaranteed to delight nature lovers.

The Fort Sumter centennial anticipated how the historical tourism industry approached the topic of slavery over the next few decades. What visitors heard when they toured the city or ventured out to area plantations in the 1960s and 1970s was not much different than what they had heard a half century earlier. Although the civil rights movement was transforming Charleston, as it was the rest of the country, change came slowly in the city’s most important industry. This had something to do with how deeply entrenched the whitewashed memory of slavery, in fact, was. But it also reflected a fundamental indifference to visitors who might prefer a more inclusive and accurate interpretation of the city’s past. In this way, the Madaline Williams affair was an apt metaphor: Charleston tourism officials did not imagine black tourists—or white tourists interested in black history, for that matter—as a part of the traveling public.

The Negro Motorist Green Book, a travel guide published from 1936 to 1964, provides one window into the anemic black tourism market in this period. Produced by an African American couple in Harlem, the Green Book helped black motorists negotiate the inhospitable environment they encountered when they took to the roads, with state-by-state entries listing hotels, restaurants, and taxi companies that were friendly to African American travelers. In the 1950s and 1960s, the Green Book never included more than five boardinghouses or hotels for black visitors to Charleston. Dining establishments in the city numbered between one and three, depending on the year, though the final edition of the Green Book published for 1963–64 included none. In theory, travel was an easier proposition for African Americans after the passage of the Civil Rights Act in 1964, which outlawed the segregation of public accommodations. In reality, the desegregation of facilities was fitful and protracted. Well into the 1970s, black travelers confronted hotels and restaurants as inhospitable as the Francis Marion had been to Madaline Williams.20

But black interest in travel was on the rise. In 1972, Time magazine announced that African Americans—with better incomes, increased access to credit, and a growing sense of comfort as legal and social barriers to travel fell away—represented “the new jet setters.” The 1970s also saw the emergence of African American heritage travel, a niche market that focused on the black past. This market arose from a confluence of forces and events: the black nationalist focus on the cultural and historical legacies of Africa; the popular interest in history inspired by the national Bicentennial celebration; and the new appeal of genealogy after the publication of Alex Haley’s Roots in 1976 and the airing of the television miniseries based on the book in 1977. Indeed, the impact of Roots on the black consciousness has been called “catalytic” and “virtually incalculable.” It not only removed the shame many African Americans felt about their slave past but also, by encouraging blacks to learn about their family history and reconnect with their cousins, spurred a black family reunion movement.21

South Carolina and Charleston boosters failed to embrace this emerging market, though they certainly appreciated the importance of travel to the economy. Domestic tourism in the United States blossomed during the 1960s, with expenditures related to travel doubling during the decade. South Carolina officials worked hard to capture some of these dollars, kicking off an ambitious national advertising campaign in 1968, the first large-scale effort to lure midwestern, New England, and Canadian travelers to the state’s sunny clime. In 1970, the director of the state tourism commission proudly announced that travel was South Carolina’s fastest-growing industry. The Charleston Chamber of Commerce also reported an uptick in tourist business, a development that was facilitated by major infrastructure improvements, including the completion of Interstate 26, which linked the city to the federal interstate highway system, and new bridges spanning the Ashley and Cooper rivers, which increased north–south travel along Highway 17. In 1968, Charleston County officials created a tourism commission to handle the influx of visitors, which by the early 1970s exceeded 1.3 million people and brought in more than $50 million annually. Yet the state’s big promotional campaign that year targeted magazines such as National Geographic, Better Homes and Gardens, Holiday, and Southern Living, not Ebony and Jet. Tourism boosters were also much more likely to look beyond American borders for new business than to the untapped African American market. In 1969, the state tourism commission sent a group of thirty South Carolinians, including eight Charlestonians, on a ten-day trip to South America to tout the state’s attractions.22

Even if boosters had actively courted black tourists, there was no guarantee that Charleston’s attractions would enthrall. A white New York Times reporter who traveled there in 1970 understood the difference perspective could make. He admitted that he found the area’s sites and history intriguing. “Yet, how does a black man see that same history?” he wondered. “How does a tour of Charleston’s Slave Market strike his soul? Does Henry Middleton’s ‘benevolent sway’ over more than 1,000 slaves conjure up sweet pictures in his mind? Does he see the same ghosts I do, or far more sinister ones?”23

The two sisters who ran the Old Slave Mart Museum (OSMM) were arguably the only tourism operators in Charleston during these years who attempted to find out. After reopening the OSMM in 1960, Judith Wragg Chase and Louise Alston Graves made modest improvements. In addition to Chase’s outreach efforts in the black community, they produced new promotional materials, rearranged some of Wilson’s exhibits, and added displays of African and Caribbean art. Chase and Graves did not change the museum’s basic organization, devoting the first floor to a gift shop and the second floor to the exhibit gallery. Nor did they update the museum’s poor lighting, rickety display cases, or handwritten signs—elements that gave the museum an amateurish feel and that Chase insisted were rooted in tourists’ preferences, making “them feel they have been transported to the slavery period.” Whether in spite or because of these homey features, Chase and Graves managed to revive the OSMM’s fortunes. In Miriam Wilson’s last year, fewer than two thousand people toured the museum. By the late 1960s, the OSMM was attracting thirty thousand visitors a year, collecting enough in entrance fees to enable Graves and Chase to hire several senior citizens and, on occasion, college students to assist them.24

The sisters hoped that these numbers would be bolstered by a wave of black tourism unleashed by civil rights victories. “Integration of public accommodations has greatly increased Negro tourism,” Chase argued in a 1970 promotional flyer, but South Carolina “has done little to capture this market.” The tricentennial anniversary of the state, which South Carolinians celebrated that year, seemed the ideal time to begin such efforts. “Tourists can, and do, choose between South Carolina and other states when they want to see the Ante-Bellum South recaptured,” she said, but if they want to visit a museum devoted to African American cultural contributions, they have no choice. “The Old Slave Market Museum is unique,” Chase argued.25

She was right. More than three decades after Miriam Wilson founded the OSMM, it was still the nation’s only slavery museum. Yet Chase’s desire to turn the OSMM into a major draw for African American visitors remained unfulfilled. Although some black Charlestonians viewed it as a valuable historical site, many ignored the museum. A small number of African American tourists continued to stop by the OSMM, as they had since it opened in 1938. Up until the time that Chase and Graves closed down the museum in 1987 because of rising costs, however, white and Asian tourists, who came from as far away as Europe and Japan, outnumbered black visitors.26

African Americans may have been put off by how Chase and Graves presented slavery. To be fair, the sisters distanced themselves from a few of Wilson’s interpretations. For instance, they continued to sell copies of her Slave Days pamphlet in the OSMM, but also posted a sign announcing, “The present operators of the Old Slave Mart Museum are in no way responsible for the opinions expressed in this booklet by the author, Miss Wilson. Written over twenty years ago, its value lies in the interesting facts of history that it presents.” Still, the sisters stayed true to Wilson’s overall vision for the OSMM, which involved underlining the gains made, and artwork produced, by the enslaved, while downplaying slavery’s brutality. “We don’t emphasize the whips-and-chains aspect of the past,” Chase insisted, “since we feel this is a museum of cultural rather than political history. But through the years, we’ve had to walk a chalk line to keep both blacks and whites satisfied.”27

This delicate balancing act had mixed results. A few cheered it. United Daughters of the Confederacy member Marguerite C. Steedman viewed the OSMM as a rejoinder to those who might criticize the plantation South. “Visitors, seeking fetters, chains, and whips, must be disappointed to find a gift shop on the ground floor and innocent handcrafts upstairs,” she wrote in the News and Courier in 1978. Franz Auerbach certainly had been. On his 1969 OSMM tour, the South African Jewish teacher was shocked to discover a museum that “gloss[ed] over the Middle Passage” and “whitewash[ed]” slavery. “When I made some remarks to the lady at the gift shop about the horrors of slavery,” Auerbach later wrote, “she argued that in general the slaves had been well looked after, and had been happy.” Some African American visitors were disturbed by the fact that the OSMM’s gift shop sold reproductions of slave advertisements to “well-to-do white tourists.”28

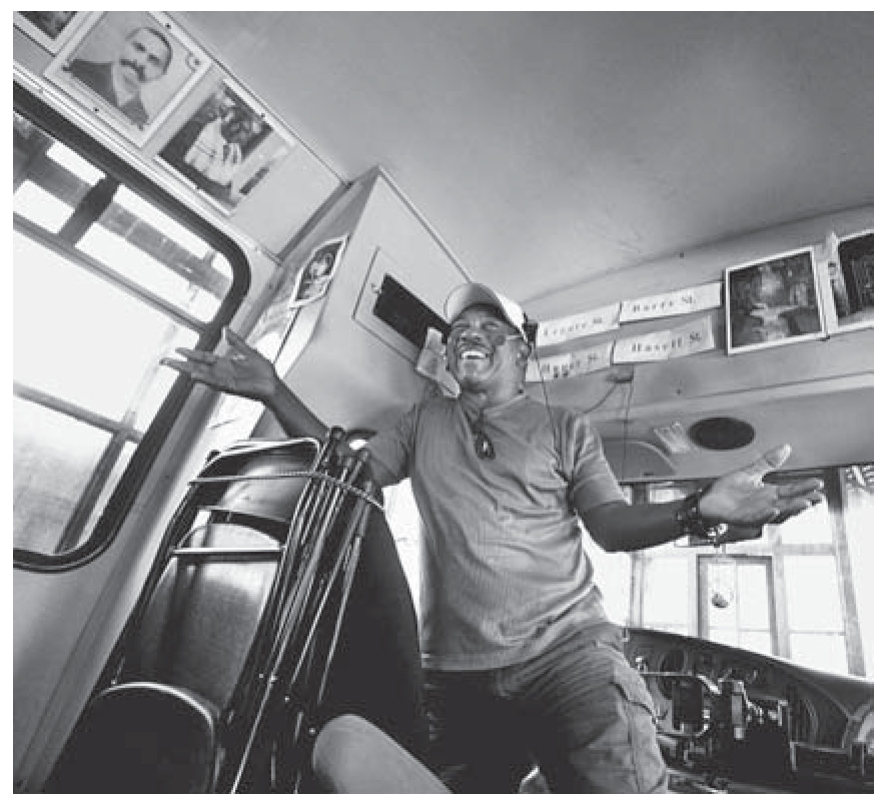

* * * *

THE BLACK HERITAGE tourism market that Chase and Graves envisioned finally emerged in the mid-1980s. By this point, Charleston was a hot spot of southern tourism, with three million visitors spending over $400 million in the city annually. Since taking office in 1975, Mayor Joe Riley had worked hard to revitalize downtown Charleston, countering the suburban flight that plagued twentieth-century American cities by fostering economic and cultural development. First, he helped establish Spoleto Festival USA, one-half of an international arts festival (the other half was hosted in Spoleto, Italy) that brought musicians, dancers, thespians, and thousands of tourists to Charleston for two weeks each spring. Second, Riley led the campaign to build a massive hotel and conference center in the heart of the city. After a protracted battle with preservationists, the $85 million project opened in 1986. The center was a commercial boon, spawning the transformation of King Street into a high-end shopping district and providing a considerable boost to a tourism industry that by the 1980s provided more jobs in Charleston than any other industry.29

In the face of criticism that these initiatives—especially Spoleto—meant little to the city’s black residents, not to mention the emerging black tourism market, the Riley administration worked with members of the African American arts community to create the Moja Arts Festival in 1984. This annual fall festival featured African, Caribbean, and African American arts and culture. Four years later, Riley arranged for the city to purchase the OSMM from Chase and Graves. The aging sisters had been trying to sell both the building and its collection since the late 1970s. After the College of Charleston, the Charleston Museum, and the Smithsonian Institution declined to buy the OSMM, they turned to the city, mobilizing portions of the black community to lobby the mayor’s office. Riley, who viewed the OSMM as “a real treasure,” said he was willing to go “digging in the back of the safe” to find the funds to save it. One year after Chase and Graves closed the OSMM in January 1987, the city paid $200,000 for the 6 Chalmers Street building, though it chose not to buy the collection contained within. It would take almost two decades, however, for Charleston to reopen the OSMM.30

In the meantime, a handful of black Charlestonians continued diversifying the city’s historical narrative. In 1983, husband and wife team Robert Small and Alada Shinault-Small had established Living History Tours. A Charleston native, Shinault-Small knew firsthand that most existing tour companies failed to do justice to African American history. Having obtained her tour guide license in 1982, she worked for one such company before she and her husband ventured out on their own. While Shinault-Small was able to incorporate black history into the tours she gave for the earlier company, she felt hamstrung. “I wanted to do it in my way,” she said, “without the constraints of an employer.”31

The other pioneer in the heritage market was Alphonso Brown, a band teacher who grew up in nearby Rantowles. Having long enjoyed entertaining visiting friends and family with his own tours of downtown Charleston, Brown decided in 1985 to become a licensed tour guide. But Brown, in contrast to Robert Small and Alada Shinault-Small, did not initially focus on black history and culture. He vividly recalled an early tour with several white women from the North who, at the end, asked, “What about the black people in Charleston? Didn’t they do anything?” Brown realized his narrative was too narrow. “When I got my license,” he explained, “I just did what they did,” meaning he mimicked the white tour guides who dominated the city’s tourism industry. Although he attended segregated schools and the historically black South Carolina State University, Brown had not learned to see the history of the Lowcountry from the perspective of African Americans. Only after his interaction with curious white tourists did Brown realize his black heritage might be a marketable commodity. Founding Gullah Tours as the main competitor to Living History, he bought a van in which to transport tourists around the city.32

Alphonso Brown, owner of Gullah Tours, was a pioneer in the black heritage tourism market. His patrons heard a narrative of Charleston’s past that was ignored on most traditional tours.

Brown’s anecdote about the birth of Gullah Tours reveals a significant point about black heritage tourism in Charleston. Just as northern white tourists pushed Charlestonians to uncover traces of the slave past in the early twentieth century, so, too, did they encourage African American tourism purveyors to tell a fuller story decades later. Small and Shinault-Small estimated that only twenty percent of the people who took their tours in the early years were African American. Black tourists, they recalled, tended to look for a jazz club when they came to Charleston, not realizing they could visit historic sites that were connected to black history. Brown’s experience was similar. “You didn’t have that many black tourists at that time.” African American visitors came to see “family and friends rather than being a tourist, and so you had mostly whites.” And they were the ones, Brown said, who motivated him and the tourism industry more generally to change. “It was a demand from the tourists . . . White tourists demanded the full story . . . These tourists are not crazy. They know we had slaves here. I mean, this is Charleston.” (As late as 2015, in fact, Brown reported that his clientele was still predominantly white.) International visitors played a role in effecting this transformation as well. “We have an especially large number of foreign visitors who are curious to know anything about the particularly American, and Southern, aspects of ‘The Peculiar Institution’ of slavery,” explained OSMM owner Judith Chase in the mid-1980s.33

These early black heritage entrepreneurs based their tour narratives on a number of sources. Brown, for example, consulted the collections at the Charleston County Public Library and the recently established Avery Research Center for African American History and Culture, located in the old Avery Normal Institute building. At Mount Zion A.M.E. Church, where he was the choir director, he talked with the older congregants, the descendants of slaves. “And oh, they talk. They tell you things. They tell you things,” Brown once said. In this way, individual memories became public memory within the African American heritage market, just as white memories had within the city’s tourism industry in earlier decades.34

A more surprising influence on Brown was the Society for the Preservation of Spirituals. As the new millennium approached, the SPS limped along, its all-white membership and antebellum costumes increasingly seeming out of touch, if not offensive. In fact, after a 1995 show, the group retired from performing in public. Several years before that, however, Alphonso Brown had attended an SPS concert. He was amazed. Grateful that the SPS was “preserving that style of music to make sure that we would always have it with us,” Brown decided to do his part, too. In 1993, he organized what became an annual “Camp Meeting” performance of Gullah spirituals by the Mt. Zion Spiritual Singers for the Piccolo Spoleto Festival, an offshoot of Spoleto Festival USA. Two decades later, in the spring of 2012, Brown brought the SPS—by then much reduced in size, at about a dozen members, and no longer sporting its Old South outfits—together with the Mt. Zion Spiritual Singers and a Stanford University a cappella group. For the first time since its founding in 1922, the SPS performed with black spirituals singers.35

As of 1985, black heritage guides like Brown also had access to a revised version of the study manual for tour guides. Local historian Robert P. Stockton spearheaded the update, which did not stray greatly from the Eurocentric focus of earlier versions. In a nod to the changing times, however, the tourism commission appointed one of its members, Elizabeth Alston, to write a new chapter called “Black Charlestonians.” Alston had introduced black history to the Charleston County school system in the 1970s and, as a recognized authority on local black history, regularly gave lectures at African American churches and organizations.36

Alston’s “Black Charlestonians” was representative of the early black heritage tourism industry in Charleston more generally. It was a necessary, and mostly accurate, revision of a narrative that had failed to do justice to the history of African Americans and slavery. Alston’s material appeared as a separate chapter located near the end of the study manual, however. One consequence of segregating this material from the traditional narrative was that the revised manual, taken as a whole, gave the impression that slavery and black history existed outside of Charleston history, that it was somehow separate from, and less important than, its “real,” white past. The 1985 tour guide manual both reflected and nurtured a segregation of the past that came to define the city’s tourism industry well into the 2000s.

Yet rewriting the narrative and remapping the cityscape in ways that recognized African American history and slavery were hardly inconsequential. While tourists had long found glimpses of the slave past at the OSMM and in King Street antiques shops that peddled slave badges, this new vision of Charleston’s past was more revolutionary in scope. Elizabeth Alston’s chapter for prospective tour guides underscored the centrality of slavery to Charleston from its founding in 1670, outlining, for example, the slave code that governed their mobility and punishment. She also detailed the long history of slave revolts in the area, including the Stono Rebellion and the plot planned by Vesey, who, “more than anything . . . wanted to secure the freedom of his people.” Alston recounted stories about slave runaways during the Civil War, the Massachusetts 54th, and the Slavery Is Dead parade. No existing guidebooks contained this perspective on the history of slavery in the Lowcountry or on the sectional conflict, though Alston’s occasionally limp prose softened the impact of her corrective. “The Vesey plot,” she wrote, “caused the enactment of laws to control Blacks.” Whether or not she intended to—and she may have, given that she was writing at the request of the city—Alston made her material more palatable with such grammatical constructions, subtly absolving white Charlestonians of their actions.37

Given their clientele—visitors who actually sought out tours about the black past—African American heritage guides had little need to be so careful. The owners of Living History immersed visitors in the antebellum and wartime black experience. As he drove around the Sea Islands, Robert Small assumed the persona of a private in the Massachusetts 54th Regiment as well as Jemmy, the slave who led the Stono Rebellion. Alada Shinault-Small portrayed a free black woman who served the Union Army as a cook and spy. Small and Shinault-Small visited sites not typically included in more traditional tours of the city, such as Emanuel A.M.E. Church, and deferred to the interests of tourists in plotting routes, incorporating places they wanted to see. Some asked to see Avery, some the alleged Denmark Vesey home, still others the Old Slave Mart Museum. Other African American heritage guides, including two newcomers—Sandra Campbell, founder of Tourrific Tours, and Al Miller, founder of Sites and Insights—visited these sites in the course of their tours, too. All of these guides also discussed topics (the Vesey conspiracy, Reconstruction) long ignored by more traditional walking, carriage, and bus tour companies. Black heritage guides, in sum, were more inclined to address the often ugly realities of the city’s past. “I don’t believe in sugarcoating history,” remarked Al Miller on a 2009 tour. “History’s history.”38

Even when black heritage guides covered much of the same geographical and historical ground as other guides, their viewpoint was fundamentally different. Alphonso Brown typically drove his Gullah Tours van down to the Battery. Rather than focusing tourists’ attention on Fort Sumter in the middle of Charleston Harbor, Brown pointed out Sullivan’s Island, just to the left. He invoked historian Peter Wood’s observation that this disembarkation location for enslaved Africans “was our Ellis Island,” before discussing the pest house where Africans were kept in quarantine prior to being transported into Charleston to be sold. Brown thus shifted the historical lens from the luxury of planter life and the military spectacle of the bombardment of Fort Sumter to the tragic realities of the Middle Passage and the auction block.39

Brown also offered an alternative view of the city’s antebellum homes. Many guides took tourists past the Miles Brewton House, which Susan Pringle Frost and her sisters had saved in the early twentieth century. Like these early preservationists, modern tour guides emphasized the home’s architectural significance, noting that it is an outstanding example of a Charleston double house. Brown, however, drew attention to the house’s iron fence and its imposing chevaux-de-frise, installed out of fear of slave insurrection. Throughout his tours, Brown issued thinly veiled criticisms of real estate agents and tour guides who used euphemisms such as “carriage houses,” “dependencies,” or “servants’ quarters” to describe the dwellings where slaves lived. Passing by the Calhoun Monument in Marion Square, Brown remarked, “If John C. Calhoun had his way right now, blacks would still probably be in slavery.”40

While many tour guides emphasized the stateliness of the Miles Brewton House, black heritage guides focused on the imposing system of spikes on the fence. These chevaux-de-frise were intended to guard against slave insurrection.

Despite their more inclusive historical vision, black heritage tour guides at times ventured beyond the historical record in their desire to challenge the silences and erasures of the traditional tour narrative. For instance, on a 2009 tour Al Miller told of how slaveholders blindfolded their slaves and then forced them to have sex with multiple partners. Enslaved women, he argued, thus did not know who impregnated them, making it easier for their owners to break up families at the auction block. Although there is no evidence of this kind of charade, Miller’s story nevertheless served an understandable purpose. He wanted to drive home how slavery rested on a perverse foundation of the profit motive and sexual violence.41

Black heritage guides also routinely took tourists by the house at 56 Bull Street, claiming it had been the home of Denmark Vesey, who, in fact, did live on that street. Informed in 2009 that experts had concluded the house was constructed after Vesey’s death, Tourrific Tours guide Sandra Campbell responded that the home had a historical plaque on it—a National Historic Landmark plaque installed in 1976—which gave it “some legality, some validity.” The unwillingness of Campbell and other black heritage guides to relinquish the idea that Vesey slept behind those very walls spoke to the absences in the city’s commemorative landscape. As Vesey biographer Douglas Egerton observed, “Imagine living in Charleston, growing up in South Carolina, and all the sites you see have ignored the fact that this was a slave city.” You would be “desperate to find some physical connection to the past.”42

* * * *

TWO DECADES AFTER these African American guides and the city had begun to rewrite Charleston’s tourism narrative, the larger impact of such efforts beyond the black heritage market remained uncertain. The city’s tour guide licensing program itself provided one indication. In the early 2000s, Sandra Campbell volunteered to judge the demonstration tours of prospective guides. On one occasion, none of the hopefuls identified any sites related to African American history. Scolding the group for its narrow focus, she was dismayed to find that several people who later had to go through the certification process again failed to incorporate black history into their second demonstration tour. “You can’t give a history of Charleston without a history of the slave labor that helped build it,” Campbell remarked.43

What Sandra Campbell meant, of course, was that tour guides should not leave the history of slavery out of the history of Charleston. Yet plenty of them did. The certification process, in other words, could accomplish only so much. Controlling what guides said once they were out in the streets of Charleston was hardly a tenable or even desirable option, and despite access to solid information about the black past in the revised study manual, many gave no sense that African Americans—enslaved or free—had ever played a prominent role in the city.

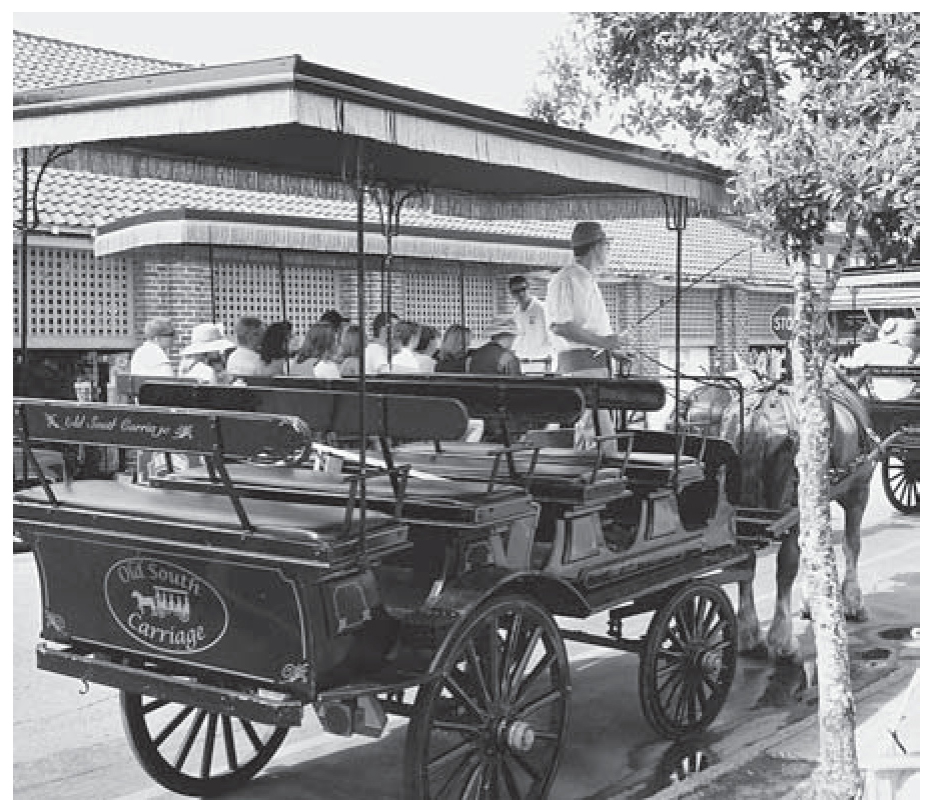

Efforts to diversify the stories told by tourism operators did not always succeed. An Old South Carriage Company tour guide in 2008 explained that all eighteenth-century Charleston residents were either English or French Huguenots, neglecting the city’s black majority.

Wearing the company’s trademark Confederate gray costume, an Old South Carriage Company guide, for example, began a tour in 2008 with a discussion of the city’s early demographics. In the eighteenth century, she said, the largest minority group in Charleston was the French Huguenots, who comprised about 15 percent of the city’s population. The other 85 percent, she explained, were English. Left unmentioned were the facts that by the early 1700s free and enslaved African Americans represented more than half of Charleston’s population, while the surrounding countryside had an even higher ratio of black to white residents.44

But it was impossible for this guide to sidestep slavery altogether. Passing the home of Nathaniel Russell, a Rhode Island merchant who moved to Charleston in 1765 and engaged in the African slave trade, she began a series of questions that amounted to a preemptive strike on tourists who might associate the city with slavery. “Which state do you think imported the most slaves in the United States?” she asked. Answer: “Rhode Island.” “Who did Lincoln ask to lead the Union army at the start of the war?” Answer: “Robert E. Lee.” This line of questioning functioned like a Lost Cause catechism. How could the South be held culpable for slavery when northern states like Rhode Island profited from the slave trade? If the Union offered such a high position to Lee, was it any different than the Confederacy, which he served for the duration of the war? “So let’s not get into this,” she pleaded. “This was just a southern thing.”45

Other guides during the same years suggested that slavery in Charleston and the surrounding Lowcountry was little more than a residential program for needy wards. On a 2012 walking tour of the city, one Kansas history buff was disappointed by his guide, who contrasted South Carolina’s supposedly gentle approach to slavery with the supposedly harsher version practiced in Deep South states like Mississippi and Texas. Other guides juxtaposed Charleston’s urban form of slavery with bondage on plantations, whether in Deep South states or closer to home. By paying particular attention to the liberties enjoyed by some Charleston slaves—the opportunity to earn money, to purchase their freedom, and to live apart from their masters—these tours effectively minimized slavery’s inhumanity by associating it first and foremost with freedom rather than bondage. Moonlight and magnolias, meanwhile, often accompanied denial and deflection. The Old South Carriage Company guide painted a portrait of antebellum Charleston by reminding the passengers that “this was the Scarlett O’Hara time.”46

The tenacity of this whitewashed narrative bothered black heritage guides like Alphonso Brown, but they also recognized it as an opportunity. “Keep in mind that the less you mention about slavery, and don’t use the word slavery,” Brown wryly announced at one gathering of tour guides, “the more that is going to fill my bus up, because people want to hear it.” His assessment may have been partly true. Brown’s business was thriving by the first decade of the twenty-first century—“ask my tax man,” he liked to say. Still, the carriage, bus, and walking tour guides who told visitors little to nothing about the history of black Charlestonians were hardly lacking for customers. Millions of tourists traveled to Charleston every year, providing a steady stream of history seekers who were happy to pay for tours cast in the more traditional mold. According to the College of Charleston’s Office of Tourism Analysis, in fact, history represented the number one reason tourists chose to visit Charleston.47

For many of these history lovers, journeying back in time was a form of entertainment, not edification, particularly if the lessons conveyed disconcerting truths about the American past. Sandra Campbell remembered a white couple that had hired her to drive them around the peninsula and then out to Middleton Place on the Ashley River. Apparently unaware that Campbell incorporated slavery into her city tour, the husband objected when she observed that the first white settlers to Charleston brought enslaved Africans with them. “‘I don’t think we want the city tour,’” he announced to Campbell, “‘Let’s just to go the plantation.’” The irony of asking to visit a plantation to avoid slavery was lost on him, though perhaps with good reason. He had been taught to view plantations as sites of romance and gentility—as gardens, as they were often advertised. While Middleton Place actually featured reenactors performing slave trades such as blacksmithing, on the day of this tour the reenactors were all white. Their race, and the nature of their work—it was skilled and not performed under the watchful eye of a mock overseer—put the tourist at ease.48

African American heritage guides were not alone in appreciating that slavery might ruffle some tourists’ feathers. Jack Thomson, a white native of Miami who relocated to Charleston in the 1960s, started leading Civil War walking tours in 1987. The popular guide made a point of discussing slavery, but broached the subject cautiously. “Is it okay to talk about slaves?” Thomson asked as a 2009 tour made its way toward the Old Slave Mart Museum. When pressed about this query, the guide admitted that some tourists grew anxious when slavery or race came up, in which case he changed the subject. Given the green light to proceed, however, Thomson launched into an awkward routine whereby he assumed the role of a slave dealer and asked a member of the tour whether he was in the market for a slave.49

Black tourists were sometimes reluctant to confront Charleston’s slave past, too. Sandra Campbell occasionally encountered resistance among her African American patrons when she brought up slavery. During one tour, a group of black teenagers became upset when she described the slave quarters behind a home located south of Broad. Their parents tried to diffuse the situation, but the youngsters said, “‘No, we don’t want to hear that,’” Campbell recalled, continuing, “They didn’t want to hear it because they didn’t want to hear about the enslavement of their ancestors. They just thought it was cruel treatment, and they became angry.” This response is an important reminder that the act of remembering slavery can cause pain—for some, even shame. Although African Americans have overwhelmingly championed forthright memories of slavery, not all of them have embraced opportunities to hear or bring to light stories that evoke sorrow and anguish.50

* * * *

AS CHARLESTON TOUR guides struggled over whether and how to incorporate slavery into their narratives in the 1990s and early 2000s, local historic sites also began to broach the subject. The Avery Research Center for African American History and Culture paved the way. Housed at the former Avery Normal Institute and owned by the College of Charleston, the black museum and archive opened its doors in 1990. Under the direction of Marvin Dulaney, a historian of black America who was hired as director in 1994, Avery started sponsoring public programs and exhibitions that drew attention to the history and culture of enslaved people.51

The National Park Service (NPS) also revamped its approach to slavery and African American history at its Charleston properties. At the local level, these efforts were led by Michael Allen, who in 1980 accepted a summer internship at Fort Sumter National Monument before his junior year at South Carolina State University. As the only African American giving tours that summer, Allen faced a bevy of questions from the park’s predominately white visitors. “‘Why are you here? What history are you going to tell us?’” he recalled them asking. Having studied African American history at South Carolina State, Allen was troubled by the scant attention that was paid to slavery in the Fort Sumter museum and bookstore and by the park’s brochure and official tour guide script. Allen decided to stay and work to reform the site from within. In 1982, he took a full-time position as an NPS ranger with the self-proclaimed mission to change how its properties addressed the black past.52

Allen began by developing temporary exhibits on figures such as escaped slave Robert Smalls. Eventually, he built up enough support and momentum that he was able to make deeper, more lasting changes. Allen was instrumental in shaping the permanent exhibit at the Fort Sumter National Monument Visitor Education Center in Liberty Square. A stark break from the NPS’s prior interpretative approach—which focused squarely on the military history of the island fort—the exhibit, unveiled in 2002, framed the fort within the context of the rise and fall of slavery in the Lowcountry and the political crisis engendered by South Carolina planters. Allen and NPS colleagues worked with Avery’s Marvin Dulaney and community members to put up a plaque commemorating Sullivan Island’s role in the transatlantic slave trade at Fort Moultrie National Monument in 1999 and to open an “African Passages” exhibit there a decade later. In 2008, that NPS site also became the site of A Bench by the Road, a slave memorial inspired by Toni Morrison. Twenty years earlier, the black novelist had given an interview about her Pulitzer Prize–winning novel Beloved, in which she observed that “there is no place you or I can go, to think about [slavery]. . . . There is no suitable memorial or plaque or wreath. . . . There’s no small bench by the road.” Inspired by Morrison’s remarks, the Toni Morrison Society worked with the NPS to install A Bench by the Road in a quiet corner of the Fort Moultrie grounds.53

Michael Allen and several NPS colleagues also took the unprecedented step of reaching out to other historic sites in Charleston to help them revise their exhibitions and programs. They worried that the progress they were making at the NPS would be overshadowed by the taint of area plantations’ and homes’ gloss on the topic of slavery. Allen and company, for instance, consulted with the Historic Charleston Foundation (HCF), which in 1995 acquired the Aiken-Rhett House in order to better illuminate the African American experience, especially slavery. When he toured emancipated Charleston in the spring of 1865, Henry Ward Beecher had twice visited this downtown property, once to interview its owner, former governor William Aiken Jr., and a second time to interview his former slaves. More than a century later, in 1996, the HCF opened the Aiken-Rhett House with an eye toward communicating the experiences of the latter. This well-preserved urban plantation complex—which includes not only the big house but also the kitchen, stables, and slave quarters where the enslaved worked and lived—offers an unparalleled window into slavery in the city.54

The historic plantations outside Charleston were slower to embrace change. Although many of these sites had been operated in a more professional manner since the 1970s—with regular house tours led by docents, for example—they had not made significant interpretive advances in terms of discussing slavery. Visitors to Magnolia Plantation, for instance, were treated to an introductory film suggesting that if you had to live life as a slave, then Magnolia “was a dream come true.” Most of the plantation’s volunteer guides avoided slavery entirely. When a journalist touring Magnolia in the mid-1990s asked his white guide about slavery there, she directed him to the slave cabin near the parking lot, adding, “‘It’s really neat.’” On the outside stood a marker that read: “This cabin offered its inhabitants more room and far greater comfort than did most of the one room, dirt floored pioneer cabins typifying those of the frontiers at the time.”55

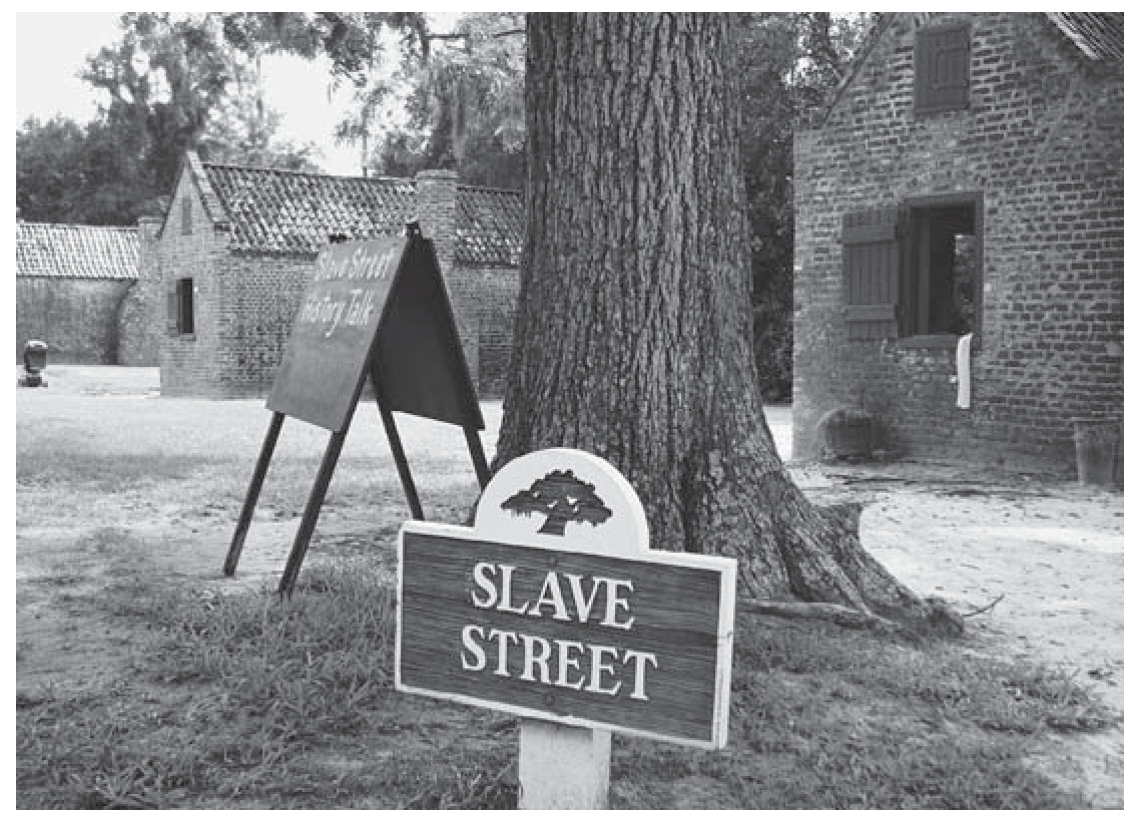

In the early 2000s, Charleston-area plantations began restoring their slave cabins. They also inaugurated black history tours, which nevertheless remained separate from those of the big house.

Charleston’s historic plantations began complicating the stories they told about slavery at the turn of the twenty-first century. Drayton Hall offered tours of its slave cemetery, while docents integrated discussions of slave life and work into the main house tour. Boone Hall restored its long-neglected slave cabins, and Middleton Place did the same with Eliza’s House, a freedman’s cabin named for a former resident. Middleton also started collecting oral histories from the descendants of African Americans who had labored on the plantation. In 2005, the plantation installed a permanent exhibit on slavery in Eliza’s House, which features a wall that lists the names of more than 2,600 enslaved people who had lived at Middleton family homes and plantations. “It’s one of those things that really affects people, probably more than anything here,” observed Middleton Place vice president Tracey Todd, who compared the wall to the Vietnam Memorial.56

By the late 2000s, all the major plantations in the area had created specific tours that address slave history and culture. When a plan to restore Magnolia’s five slave cabins was announced in early 2006, Taylor Drayton Nelson—a descendant of the original owners and the site’s director—said, “Interpreting African-American history at plantation sites is something that’s becoming essential to do across the country. . . . We’re trying to tell stories out here beyond the stories of men who built gardens and did grand political things. There are other stories to tell.” Local plantation operators also realized that those stories sold. “There were times in our history where people didn’t want to hear the slaves[’] story,” said Middleton’s Todd in 2008. “I think, basically, we’ve gotten to the point now where the market demands it.”57

These slavery tours could not have been more different from what tourists heard and saw in the main houses in most Charleston-area plantations and house museums. On Magnolia’s From Slavery to Freedom tour, which debuted in March 2009, visitors listened to a twenty-five-minute talk on African American history from the colonial period until the civil rights era as they sat near the plantation’s five slave cabins, hundreds of yards from the big house. The guide then encouraged visitors to wander through the cabins, which had been restored to re-create five distinct moments in African American life at the plantation—1850, 1870, 1900, 1926, and 1969. New York Times reporter Jim Rutenberg judged the tour a “powerful . . . reminder of the brutal condition of the slaves” that “offered vivid sugar-free descriptions of slave life.” Designed by D. J. Tucker, a Canadian who had a master’s degree in history from the College of Charleston, the tour was rooted in modern scholarship rather than in white family lore. Tucker and his fellow interpreters discussed the Middle Passage and distinctive elements of Lowcountry slavery, such as the task system, paying particular attention to black achievements and contributions.58

Still, what was conspicuously absent on slave history tours at area plantations was a forthright discussion of the violence and coercion that were endemic to plantation life. In this way, these tours did not break from the pattern set by Miriam Wilson at the OSMM in the 1930s and perpetuated under Graves and Chase. The market may have demanded slavery tours, but only tours that went so far.59

The mostly white visitors who took these slavery tours reacted in different ways. Many were shocked by what they heard; others were angered or saddened. A few even insisted that the refusal of these tours to spend much time on the suffering of slaves on Lowcountry plantations amounted to whitewashing. Denial abounded, too. Some northern tourists balked at the suggestion that merchants from Rhode Island had once played a central role in the transatlantic slave trade, while southern tourists often disputed the contributions made by the enslaved. In 2011, Magnolia interpreter Preston Cooley recounted that some “angry white people” on his tour remarked that “those Africans were heathens, that they were not smart, and that all this stuff we’re peddling is nothing but clap trap.”60

The new black heritage tours began to attract more African American visitors to Charleston plantations, which was no small development. Black tourists had long been reluctant to venture out to such sites. According to the interpreters at Magnolia, when the From Slavery to Freedom tour first opened in 2009, there was a good deal of skepticism by African Americans, who assumed that the Draytons were simply trying to make themselves feel better. But the Magnolia guides reported that most black visitors were impressed by the restored cabins and the tour, and many were emotionally overwhelmed by the experience. Preston Cooley described African Americans who came up to him with tears in their eyes and thanked him for “finally telling the truth about their ancestors.” Although whites still represented the vast majority of visitors to area plantations, black visitors to Magnolia had surged upward by more than 30 percent as of 2015, largely fueled by the From Slavery to Freedom tour.61

The new presence of African Americans, however, unsettled some. In 2014, a Magnolia guide described an incident in which a truck flying a Confederate flag drove slowly by the slave cabins while she talked to a group that included some African Americans. Someone in the vehicle shouted, “All of y’all are going to be our slaves again. The South will rise again!” On another occasion, a tour guide from the city walked by a group headed toward the From Slavery to Freedom tour and quipped, “Don’t work these slaves too hard.” To its credit, Magnolia banned the guide from the property.62

Despite the growing popularity of these slave cabin tours, well into the twenty-first century they remained on the margins of the plantation tourism experience. When Jim Rutenberg first toured Magnolia Plantation in May 2009, for example, he completely missed the fact that a slave history tour was also offered. He was embarrassed, he later wrote, to learn about it only while on a second visit a month later. Rutenberg’s experience is not surprising. At Magnolia, Middleton, and Boone Hall, tours that focused on the slave experience were separate from tours of the primary attraction—the big house—which continued to dwell on the home’s architecture, antiques, and white owners. More inclusive than they once were, the plantations surrounding Charleston separated white and black history, enabling visitors to avoid confronting slavery if they wanted to.63

Even properties that sought to integrate slavery into their main house tours did not always live up to their inclusive ideal. On one October 2005 tour of the Aiken-Rhett House, a docent highlighted the experiences of the men, women, and children who lived in the slave quarters behind the mansion. But on a second tour, taken the following day, a different guide lingered for most of the tour in the stately rooms of the mansion, reminiscing about the glorious days when elite Charlestonians “danced the night away.” As a guide from the Nathaniel Russell House, another HCF property, observed in 2009, older docents who had been leading tours for decades had difficulty incorporating the new emphasis on slavery into their presentations. Despite explicit instructions, he explained, “they will not call the servants ‘slaves.’” The inclusiveness of a particular house tour, then, was largely dependent upon the docent visitors were assigned. In the early 2000s, the Aiken-Rhett House shifted to self-guided tours facilitated by handheld audio devices for all but the largest tour groups. While this change theoretically precluded the moonlight-and-magnolias approach of old-timers, the independence the devices afforded—visitors could pick and choose which parts of the property to view—still provided an opening for the ongoing segregation of Charleston’s past.64

Much the same was true in the streets, vans, and carriages of Charleston. A handful of traditional tour guides (those, that is, who did not necessarily bill themselves as African American heritage guides) did a superb job of integrating the black and white narratives of the city’s history. Yet such guides were few and far between. Tourists who arrived knowing that they wanted to learn about the city’s black past had to “deliberately seek it out,” in Sandra Campbell’s words. The majority of tour guides—whether on foot, behind the wheel, or at the reins of a carriage—interpreted and disseminated one of two discrete narratives about the city’s past. A half century after Charleston rid itself of separate water fountains, hotels, and restaurants for blacks and whites, in the city’s central industry segregation ruled.65