IN THE FALL OF 2010, A GROUP CALLED THE CONFEDERATE Heritage Trust announced that on December 20 it would hold a Secession Gala in Gaillard Municipal Auditorium. For $100 a ticket, Confederate enthusiasts could attend a costume ball to celebrate South Carolina’s decision to secede from the Union one hundred and fifty years earlier. In the weeks leading up to the ball, Jeff Antley, the organizer, proposed that it was a commemoration of the brave men who “stood up for their self-government and their rights under law.” The event, he insisted, “has nothing to do with slavery.”1

Once word got out about the ball, and especially about the Trust’s declaration that the event—and the act of secession—had no connection to slavery, it attracted a chorus of ridicule from national pundits and comedy programs, including The Daily Show with Jon Stewart. Civil rights groups took the Secession Gala more seriously. The NAACP announced that it would lead a day of demonstrations. “It’s amazing to me how history can be rewritten to be what you wanted it to be rather than what happened,” South Carolina state chapter president Lonnie Randolph observed. “You couldn’t pay the folks in Charleston to hold a Holocaust gala, could you?”2

The NAACP protest began with an organizational meeting at Emanuel A.M.E. Church. Inside the church basement—just beyond a vestibule that houses a small sculpture of four black children commemorating Denmark Vesey’s planned rebellion—the group listened to a few inspirational words and planned its route. The protesters, mostly black, but some white, then made their way down Calhoun Street to picket in front of the Francis Marion Hotel, one of the official hotels for gala guests and the locus of the centennial segregation controversy a half century earlier. They carried signs that read, “It’s Not About Heritage” and “South Carolina Suffers from a Confederacy of the Mind.” Charleston NAACP chapter president Dot Scott minced no words about why they were there. “Celebration in the form that they are doing at Gaillard,” she explained as she made the long picket loop in front of the hotel, “it’s just not acceptable.” Scott made it clear that the NAACP had no quibble with the commemoration of secession. It was the festivities—the dinner, the dancing, the clinking of mint julep glasses, all mixed with a hearty dose of denial—that were inappropriate.3

Later that evening, several hundred revelers, dozens decked out like cavalier planters and southern belles, gathered for the gala at the auditorium, located across the street from Emanuel A.M.E. Escaping the chilly winter air and the cold stares of protesters, they walked briskly into the hulking midcentury structure, passing by the controversial portrait of Denmark Vesey. The mood inside was festive and defiant. Asked why they had paid the $100 price of admission, attendees spoke of the bravery and sacrifice of their ancestors. Many connected secession to the Tea Party movement, insisting that its leaders were fighting for the same thing that their Confederate ancestors had fought for one hundred and fifty years before: smaller government and lower taxes.4

After a cocktail hour, the guests watched a reenactment of the 1860 secession convention staged by a cast that included several state and local politicians. Glenn McConnell, state senator and senate president pro tempore, played the role of convention president D.F. Jamison. After McConnell (as Jamison) declared South Carolina an independent nation, the delegates led the audience in a rousing rendition of “Dixie.” Outside at the NAACP’s candlelight vigil, one NAACP leader reminded the world of what it all meant: “Slavery is what you defend when you have a party, a celebration, get drunk, holler loud, act like a rebel, and talk about how you’re celebrating your heritage. No matter how you dress it up, it is still slavery.”5

The gala-goers mostly shrugged their shoulders at the hoopla. One guest even welcomed the protesters. “They actually helped ticket sales,” argued Harry B. “Chip” Limehouse, a state representative and secession convention reenactor. “We’d like to thank them,” he added. “Without them, we wouldn’t have made bud get.”6

Limehouse was on to something, for the Secession Gala was not as grand as anticipated. The Confederate Heritage Trust had made five hundred gala tickets available to the public, but it managed to sell only about four hundred, despite heavy publicity. What’s more, just three hundred or so people actually attended the ball, and a handful of them were journalists and scholars who were there to cover the story, rather than toast secession. It was a far cry from the more than sixty thousand people who flooded the city during the centennial back in 1961.7

Nor was the Secession Gala widely embraced by local officials or media outlets. Many prominent South Carolina voices joined the NAACP in decrying the event. Just days before the gala, the Post and Courier—the city’s main paper since the Evening Post and the News and Courier combined in 1991—printed an op-ed by its former executive editor explaining how slavery was the central issue that drove South Carolinians out of the Union. Robert Rosen, president of the Fort Sumter–Fort Moultrie Historical Trust, which coordinated Charleston’s official Civil War sesquicentennial observances, disavowed the Secession Gala. “The Trust believes that slavery was an abomination and therefore cannot celebrate a political event which the participants themselves believed was designed to continue the institution of slavery,” Rosen declared in a statement. The State, the leading newspaper in the South Carolina capital, published two editorials that similarly railed against a celebration of secession. And although several politicians performed in the play reenacting the secession vote, Mayor Joe Riley denounced the gala affair. He emphasized that the ball was a private event that had not received any assistance or encouragement from the city.8

The morning of the gala, in fact, Mayor Riley dedicated a historical marker at the former location of Institute Hall, where the Ordinance of Secession was signed in December 1860, before a crowd of about one hundred people. In his remarks, Riley stated unequivocally that “the cause of this disastrous secession was an expressed need to protect the inhumane and immoral institution of slavery.” This was too much for one member of the crowd, who yelled “You’re a liar!” echoing South Carolina congressman Joe Wilson’s infamous outburst during a 2009 speech by Barack Obama. This lone voice of dissent was overshadowed by the approval of the majority of those in attendance, and the ceremony proceeded without further incident.9

The events of December 20, 2010, are an apt symbol of how Charlestonians remembered slavery nearly a century and a half after its abolition. As shaped and promoted by black activists, scholars, and city hall, Charleston’s public presentation of slavery was not nearly as whitewashed as it had been even fifty years before, when locals marked the centennial of the Civil War. In 1961, the sectional tension over segregation that erupted in advance of the celebration—and that resulted in southern delegations seceding from the national convention—recalled the conflict that had begun in Charleston a century earlier. By 2010, a commemoration of the Civil War driven by the tenets of the Lost Cause was inconceivable. Still, defenders of whitewashed memories of the peculiar institution, though not as numerous or vocal as before, had not altogether retreated from the scene. Charleston’s Civil War sesquicentennial offered concrete signs that the capital of American slavery was inching its way toward a full reckoning with its past, even if not every one welcomed the move.

* * * *

MAYOR RILEY’S MARKER dedication, rather than the Secession Gala, was a bellwether for Charleston’s official Civil War sesquicentennial commemoration. Over the next four years, the Fort Sumter–Fort Moultrie Historical Trust brought together a wide range of figures, including National Park rangers, city officials, Civil War historians, and members of Confederate heritage groups, to stage a commemoration that was sober, reflective, and inclusive. Led by Robert Rosen, an attorney and historian as well as president of the Trust, this coalition took the city’s centennial as a blueprint for what not to do.10

The most prominent part of the commemoration was a weeklong series of events in mid-April 2011 marking the anniversary of the firing on Fort Sumter. It was a study in contrasts with the celebration held fifty years before. While the Fort Sumter centennial drew comparisons to a raucous football game, the centerpiece of the sesquicentennial in 2011, held in White Point Garden, seemed at once a summer concert and a funeral observance. The program comprised slave spirituals, Civil War tunes, and classical compositions as well as brief remarks by nationally renowned historians and local politicians. The audience of roughly one thousand people—including a handful of reenactors—listened quietly for most of the evening. Even when urged to sing and clap along, they remained reserved. The only departure from this pattern came when the performers on stage struck up “Dixie.” Enthusiastic shouts and more spirited applause briefly filled the air, evoking the 1961 commemoration held at the same location. The solemn atmosphere quickly returned as the band transitioned to the “Battle Hymn of the Republic.”11

The substance of the 2011 Fort Sumter commemoration also bore little similarity to the centennial commemoration. Rather than focusing primarily on military maneuvers, the events emphasized the war’s broader social and political context. The speakers at White Point Garden, for example, stressed that slavery had sparked the conflict, that African Americans had played a key role in the war, and that the most significant outcome of the conflict was emancipation. Nodding to Emancipation Day celebrations of the late nineteenth century, Mayor Riley read selections from Abraham Lincoln as the orchestra played Aaron Copland’s “Lincoln Portrait.” And while the crowd that gathered to watch the performance that night was overwhelmingly white, the area’s racial diversity was a central feature of the program. Still directed by Gullah Tours operator Alphonso Brown, the Mt. Zion Spiritual Singers sang. Columbia University historian Barbara Jeanne Fields, granddaughter of Mamie Garvin Fields, who had enjoyed Fourth of July commemorations on the same spot, addressed the crowd. Even the reenactors who participated—members of the Palmetto Battalion and 54th Massachusetts Regiment—reflected this spirit of inclusivity. White Confederate and black Union soldiers marched in and stood together as a combined company.

Later sesquicentennial events continued to highlight the role of slavery and the participation of African Americans in the conflict. On the anniversary of Robert Smalls’s dramatic May 1862 escape from Charleston aboard the Planter, the city dedicated two Smalls memorials—an interpretative plaque at Waterfront Park and a historical marker on East Bay Street in front of the Historic Charleston Foundation—and held a panel discussion on Smalls’s legacy. The following summer, Charleston marked the anniversary of the Union assault on Fort Wagner, which was led by the Massachusetts 54th, with living history demonstrations, a screening of Glory, a public forum at the Dock Street Theatre, and the dedication of a marker to the black regiment at the Battery, which looks out toward the spot where Fort Wagner once stood. Finally, on April 19, 2015, a small group gathered in Hampton Park to commemorate the first Decoration Day ceremony that former slaves had held at the Martyrs of the Race Course cemetery one hundred and fifty years earlier. The program on that gray and breezy afternoon included brief remarks by historian David Blight, who was responsible for rediscovering the momentous event, Clementa Pinckney, a pastor at Emanuel A.M.E. Church, and Citadel chaplain Joel Harris. That a black representative of Denmark Vesey’s former church and a white representative of the military academy founded in the wake of his failed insurrection came together to pay their respects to the Union fallen underscored how much had changed in Charleston.12

Yet the sesquicentennial commemoration was not without its critics. The staff at the Confederate Museum, operated by a local United Daughters of the Confederacy chapter, complained about the emphasis on race in the speeches given at White Point Garden during the Fort Sumter program. So, too, did a local conservative talk radio host, who was disappointed that Mayor Riley and his fellow speakers repeatedly brought up the issue of slavery.

Meanwhile, the Charleston Mercury struck a defensive pose throughout much of the four-year Civil War commemoration. The conservative bimonthly had been revived in 2000 by Charles W. Waring III, a publisher who came from a long line of local journalists, including his great-grandfather Thomas R. Waring, who edited the Charleston Evening Post, and his great-uncle Tom R. Waring Jr., who edited the Charleston News and Courier during the tumultuous years of the civil rights movement. Unlike the Rhetts’ Mercury, which never bothered to deny that slavery was the issue that precipitated the war, Charles Waring’s version of the paper announced in its special Civil War sesquicentennial magazine that it intended to contest “the simplistic notion that the War was ‘over slavery,’” a notion that was foisted upon the South by “partisan Northern historians” after the conflict and that persists to the present. Waring admitted that slavery played a role in the conflict, and he even commissioned a series of columns on the peculiar institution written by African American journalist Herb Frazier. On the whole, however, his paper’s sesquicentennial coverage emphasized that slavery was a national, rather than a southern, problem. Like many of his Lost Cause forebears, Waring was more concerned with drawing attention to the moral failings of antebellum northerners—who had “no urge to liberate the slaves”—than with probing the motivations of Confederate leaders. And when it came to what brought on the Civil War, he called for an end to “the need to ride the broken down horses of single causality and vilification of the South.”13

On one occasion, opposition to the commemoration’s interpretative bent took the form of action, not words. In June 2012, vandals struck the Robert Smalls marker on East Bay Street, just one month after its installation. Under the cover of darkness, someone ripped the marker from its pole, which was embedded in the promenade several feet above the street. “I know a car didn’t hit it up there,” National Park Service ranger Michael Allen remarked after the incident. “Whatever happened to it was done on purpose.” Staff at the Historic Charleston Foundation suspected the culprit or culprits had hitched a truck to the pole to loosen it from its concrete moorings. City workers reinstalled the marker a month later.14

* * * *

BY THE 150TH anniversary of the Civil War, a confluence of factors—black political empowerment and activism, growing support from city hall, tourist demands, and new leadership at numerous historic sites, among others—helped make black history, and especially the history of slavery, a more central part of the tourist experience in Charleston and the city’s self-image. Of course, the peculiar institution had been a component of a visit to the city since 1865. But by the second decade of the twenty-first century, this dark chapter had become not only a more prominent feature in Charleston’s self-presentation—it was a topic that the city finally began treating in an honest and forthright manner.

The Old Slave Mart Museum, which the city reopened in 2007, emerged as a leader in this revisionary process. Unlike the museum’s first two iterations, or any other tourist attractions in the area for that matter, the new OSMM focuses primarily on the city’s role in America’s domestic slave trade. The museum draws visitors’ attention to the unique nature of the 6 Chalmers Street site when they first arrive, informing them in a large sign in the orientation area that “in the mid-1850s, slave traders came to this place to buy and sell African Americans—an interstate trade that brought wealth to Charleston, the state and the region.” The OSMM’s small permanent exhibit features objects, such as whips and shackles, and audiovisual effects, such as the sounds of an auctioneer’s call, that bring human trafficking to life. Visitors remark on the emotional impact of learning about the slave trade in a place where it was once conducted. Robert Norman, an African American from Chicago, felt excitement to “stand in the spot where people were sold into slavery,” but he also felt anger at what “they had to go through.”15

Eight years later, as the sesquicentennial wound down, the Charleston County Parks and Recreation Commission began welcoming visitors to McLeod Plantation, a former Sea Island cotton planation and Freedman’s Bureau headquarters that places African Americans’ experiences during slavery and its aftermath at the center of its exhibits. “The story of McLeod Plantation is a tale of tragedy and transcendence,” reads the plantation’s welcoming sign. “Through generations of enslavement, a brutal war and the challenges of building lives amidst institutional inequality and oppression, African-Americans asserted their humanity while white plantation owners struggled to maintain power and wealth.” Tour guides focus on the grueling labor required to grow Sea Island cotton and direct visitors toward “transition row”—a series of cabins that housed slaves and later free African Americans. The main house, built in 1855, is an afterthought at McLeod. At the end of the outdoor tour, guides inform visitors that they can wander through the home if they wish.16

One of the more unusual initiatives of recent years is the Slave Dwelling Project, which was created by Joseph McGill, an African American Civil War reenactor from nearby Kingstree. McGill worked as a park ranger at Fort Sumter and Fort Moultrie from the late 1980s to the mid-1990s. Tony Horwitz had featured him in his 1998 Confederates in the Attic—McGill was the ranger on duty when the author toured Fort Sumter—which in turn led to McGill’s appearance in a History Channel documentary about reenactors and the controversies over Confederate monuments and the Confederate flag. In The Unfinished Civil War (2001), McGill portrayed a black soldier in the Massachusetts 54th. During production, the filmmaker suggested adding a little “spice” to the documentary. McGill mentioned an idea he had been entertaining: spending the night in a slave cabin. The filmmaker was game, and so McGill arranged to sleep in a Boone Hall slave cabin for a night. “The floor was very hard, and the bugs were terrible,” McGill recalled. “I am not sure ‘spooky’ is the word, but the thought did run through my head of all those who had tried to escape.”17

Nearly a decade later, McGill consulted on the restoration of the 1850s slave cabins at Magnolia in his capacity as a program officer with the National Trust for Historic Preservation. On March 8, 2010, McGill slept in a newly restored cabin at Magnolia, and the Slave Dwelling Project was born. Within a year, he had spent the night in cabins at a half dozen other plantations, including McLeod Plantation and Hobcaw Barony in Georgetown. Initially, McGill chose sites in or near Charleston and the Lowcountry, but over time he ventured farther from home. By 2017, he had slept at over ninety sites, including several outside the South. Since not all of the structures he visits necessarily qualified as cabins, he chooses the more capacious “dwelling” to describe them.18

McGill’s primary goal is to encourage the preservation of the old buildings. Although some owners are already on board with preservation, others are not, or lack the resources to make repairs, and the dwellings on their properties have deteriorated. McGill suggests that owners contact the local press to cover his visit, with the aim of raising awareness about preservation and potentially attracting tourist dollars to help defray costs. McGill is not a purist, however. He does not insist that slave dwellings have to be restored to the way they used to be. This approach is impractical, he argues, since many structures were repurposed decades ago as garages, storage sheds, or apartments. He cannot demand that a dwelling be turned into a museum. If an owner needs rental income to keep a structure intact, so be it. “All I ask is that we preserve and interpret them,” declares McGill. Interpretation—“telling the whole story” about how the structures were originally used and not just talking about the big house—is more important to him.19

But telling the whole story can make for an uncomfortable experience, and it is this vexing reality that motivates McGill, too. “The point I am trying to make in this,” he says of the project, “is that we should not be ashamed of our ancestors.” Shining a bright light on the conditions in which slaves lived is one way to emphasize their resiliency. Yet even McGill has his limits when it comes to such confrontations. Terry James, a black friend and fellow Civil War reenactor from Florence, occasionally joins McGill for overnight stays at South Carolina slave dwellings. On James’s second stay, he brought two pairs of slave shackles. James wanted to sleep in shackles to simulate the experience slaves endured on ships during the Middle Passage. James offered the second pair to McGill. He declined, noting, “That’s too much for me.”20

As McGill has labored to draw attention to the places in which slaves ate and slept, community activists, scholars, and municipal authorities have worked to reframe the city’s public history and refashion its public spaces. In 2011, for example, the Historic Charleston Foundation issued a revised training manual for aspiring tour guides. Although the new version builds on earlier editions of the manual—and thus does not entirely overcome earlier evasions on Civil War causation or the segregation of white and black history—it is vastly improved. Written by local historians, essays such as “Plantation Life,” “Charleston, South Carolina: The Site of Slavery,” and “A Century of Hardships and Progress” provide prospective guides with a wealth of well-researched material on black history in Charleston. The streets and squares of the city, moreover, are now home to more than a dozen historical markers that memorialize the black freedom struggle from the antebellum period through the civil rights era. In addition to the Institute Hall and Robert Smalls markers, today there are plaques commemorating the first Decoration Day in Hampton Park, the East Bay Street home of white abolitionists Sarah and Angelina Grimké, the 1945–46 Cigar Factory Workers Strike, and the 1969 Hospital Workers Strike, among others.21

Most recently, on March 10, 2016, a “slave auctions” historical marker was unveiled in front of the Old Exchange Building at East Bay and Gillon streets. Sponsored by the Old Exchange Building and the Friends of the Old Exchange, the plaque highlights the fact that “Charleston was one of the largest slave trading cities in the U.S.,” pointing out its role in both transatlantic and domestic trafficking. As one scholar noted at the dedication, the plaque was the start, not the end, of Charleston’s rethinking of its enslaved past. “At a mere 150 words, it can merely nod at a much bigger story,” he said. “It’s up to us as Charlestonians to tell the bigger story.” Joseph McGill, who also spoke at the unveiling, agreed. Much more needs to be done to rewrite “the mint julep, watered-down, hoop-skirt version of the story that we’ve gotten for too long.”22

As of 2020, that bigger, un-watered-down story will be on display in Charleston at the International African American Museum. Proposed by Mayor Joe Riley in 2000, the museum will document the black past in America from the transatlantic slave trade to the present. As Riley argued in making his case for the project, “African American history has been slow to be taught for a lot of reasons and, of course, slavery was not discussed because it was a source of shame and embarrassment for people of all races. But if we do not understand and present our past, we are shortchanging ourselves and future generations.” The $75 million museum, to be funded equally by private donors and local and state governments, will be located on the former site of Gadsden’s Wharf on the Cooper River, where an estimated one hundred thousand slaves were offloaded into the city to be sold.23

* * * *

PERHAPS THE MOST telling embodiment of the changing culture of Charleston—and of the small but still vocal group of holdouts who resist it—is the monument to Denmark Vesey. Erected in 2014 in a secluded grove in Hampton Park, the statue was the brainchild of Henry Darby, an African American teacher. Though a Charlestonian, Darby had not learned about Vesey until 1971, his freshman year at Morris College, a historically black college in Sumter. Darby’s ignorance was not entirely unusual. Black Charlestonians had nurtured stories about Vesey’s plot well into the twentieth century, and they succeeded in memorializing him with the portrait at Gaillard Municipal Auditorium back in 1976 after proposals for a statue fell on deaf ears. But not every black Charlestonian knew Vesey’s story, and even some who did may have pretended otherwise. In 1999, two elderly members of Vesey’s Emanuel A.M.E. Church told a New York Times reporter that they grew up having never heard of the black revolutionary. “I don’t know whether our parents, or even our grandparents, knew who he was,” said one octogenarian. “But if they did, they were afraid to talk about it.”24

Henry Darby hoped to change that. One day in the mid-1990s, as he walked through the peninsula, he pondered the absence of monuments commemorating the black past and hatched his plan to memorialize Vesey with a statue. In 1996, Darby recruited several members of the local black academic community to help him spearhead the project, among them historians Bernard Powers, Donald West, and Marvin Dulaney, and Avery Research Center curator Curtis Franks. Naming their group the Spirit of Freedom Monument Committee (SFMC), they approached the city with the Vesey memorial idea. To the SFMC, Marion Square seemed the best place for a public monument to Vesey. Not only is it centrally located, but it is also home to the original Citadel (since converted into a hotel). Although Mayor Riley supported the proposal, the final decision to place the memorial in Marion Square belonged to neither him nor the city council. Two nineteenth-century militias—the Washington Light Infantry, which has close historical ties to the Citadel, and the Sumter Guard, Edward McCrady’s old Redeemer rifle club—own Marion Square and lease it to the city of Charleston for public use.25

Vesey’s modern fate was, to a large extent, in their hands, and they were not eager to inscribe the revolutionary’s actions in stone in their square. Indeed, they made sure it did not happen. The militias’ public explanation for rejecting the proposal revolved around a practical concern. Marion Square was undergoing a multimillion-dollar renovation financed by the city (an extensive plan that included, among other alterations, the removal of the fence surrounding the Calhoun Monument). The Washington Light Infantry argued that no new monuments should be constructed until the redesign was complete. But when the SFMC and the militias met to discuss the Vesey plan, it was an ideological objection that loomed largest. Behind closed doors, the militias charged that Vesey was a criminal who should not be memorialized. As a compromise, militia members proposed a monument to slavery as well as to Native Americans, one that could include Vesey but only as a part of a much broader commemoration of oppression. Interpreting this alternative as an attempt “to blunt the impact of Vesey,” according to College of Charleston historian and committee member Bernard Powers, the SFMC declined the offer and decided to find a new location for the memorial.26

By 2000, the committee had settled on Hampton Park. While the park does not attract the same volume of tourist traffic as does Marion Square, it has important symbolic ties to Vesey and the black community’s century-and-a-half-long struggle to publicly recognize slavery. Located adjacent to the current campus of the Citadel, where the college moved in 1922, Hampton Park was, of course, home to the original memorial to slavery in Charleston, the Martyrs of the Race Course cemetery. There is also a personal tie to Vesey that has not been widely recognized: the Grove, a neighboring plantation once owned by Vesey’s master, Joseph Vesey, was carved from the same estate as the Washington Race Course, which became Hampton Park. Joseph Vesey, and perhaps even Denmark himself, may have walked those grounds two hundred years earlier.27

The same year the SFMC selected its Hampton Park site, it won approval from the city’s Arts and History Commission for its design and secured $25,000 from the city council to go toward the statue. Additional appropriations from the city—as well as private donations—would follow. Still, the path from approving the plans to erecting the monument was hardly smooth. Critics spoke out, giving public voice to the militias’ private objections. The lone member of the Arts and History Commission to vote against the project, for example, denounced Vesey and his co-conspirators’ alleged methods. Commission member Charles W. Waring III, publisher of the reincarnated Charleston Mercury, said he would support a more general monument to those who fought for their freedom, Vesey included, but insisted that he could not support one for Vesey alone. “Is it appropriate to massacre individuals,” Waring asked, “or to slowly win one’s freedom through the process? That’s what it boils down to.”28

When another memorial commemorating oppression was proposed for Marion Square in the mid-1990s, however, locals voiced little opposition at all. The Holocaust Memorial, installed in the square by the Charleston Jewish Federation in 1999, pays tribute to victims of the World War II genocide and to survivors who moved to South Carolina. The largest monument in a Charleston city park, covering 6,000 square feet, it is a testament to the cooperation of the Washington Light Infantry, the Sumter Guard, the city of Charleston, and the Charleston Jewish Federation. The Holocaust Memorial elicited no major protest or controversy. (The proposal for the memorial was approved, in fact, before the Marion Square redesign plan had been fully finalized.) Most letters to the Post and Courier were supportive, citing the need to remember lest the tragedy happen again. Said a Charleston Jewish Federation member: “I have an issue with people who see the Holocaust as simply a Jewish issue. It’s a watershed in human history. It shows the power a state can wield against its own citizens.” A plaque installed on the monument itself echoes these comments, proclaiming that “we remember the Holocaust to alert ourselves to the dangers of prejudice, to express our outrage at the scourge of racism, and to warn the world that racism can lead to genocide.”29

The Vesey Monument seemed to the SFMC a natural complement to the Holocaust Memorial. Indeed, this affinity was one of the reasons the committee pushed to erect its monument when and where it did. In floating its idea for a Vesey memorial as the Holocaust Memorial was under way, committee members wanted to “develop a kind of intellectual synergy between the two,” as Bernard Powers recalled. By recognizing the horrors of both slavery and genocide, Marion Square would become a place to contemplate the “inherent humanity . . . of all people” as well as “the depths to which human depravity can sink.” The name of their organization—the Spirit of Freedom Monument Committee—was chosen to evoke this broad vision of the long struggle against injustice.30

The challenges the committee faced in pushing this vision were perhaps no better captured than by the Boston architect hired to design the Holocaust Memorial. “Charleston is a paradise,” he stated when asked about the project. “That was my impression when I visited it for the first time.” How, he wondered, could he design a memorial “for something that ghastly in a place that represents the best of what the human experience has to offer? Bringing those two things together was a crisis for me.” The architect’s observation epitomized the very erasure the SFMC hoped to combat—the idea that there was no ghastly history in Charleston. It also highlighted an odd reality about public memory in the city and in America more generally. If the Holocaust is easily invoked for the purposes of drawing universal moral lessons, the same is not true for American slavery. For some, it is just too close to home. “Jewish history,” as Henry Darby remarked, “does not remind white America of a black past.” By erecting the Holocaust Memorial in Marion Square, yet rejecting the Vesey Monument in the same location, Charlestonians denounced racism abroad while overlooking a long history of it in their own backyard.31

After the Holocaust Memorial was installed, writer Jamaica Kincaid tried to point out this commemorative sleight of hand during a visit to Charleston. In town to speak at a gardening conference, Kincaid had noticed the jarring juxtaposition between the new Holocaust Memorial and the Calhoun Monument in Marion Square. Abandoning the presentation she had planned to give at the gathering, Kincaid instead discussed the green space at the heart of the peninsula. She remarked to her audience that it must be difficult for local blacks to walk by the Calhoun Monument. “Then I said,” she later wrote, “that John Caldwell Calhoun was not altogether so far removed from Adolf Hitler; that these two men seem to be more in the same universe than not.” The chairman and founder of the organization, who had invited Kincaid to speak, scolded her for her remarks: “I had done something unforgivable—I had introduced race and politics into the garden.”32

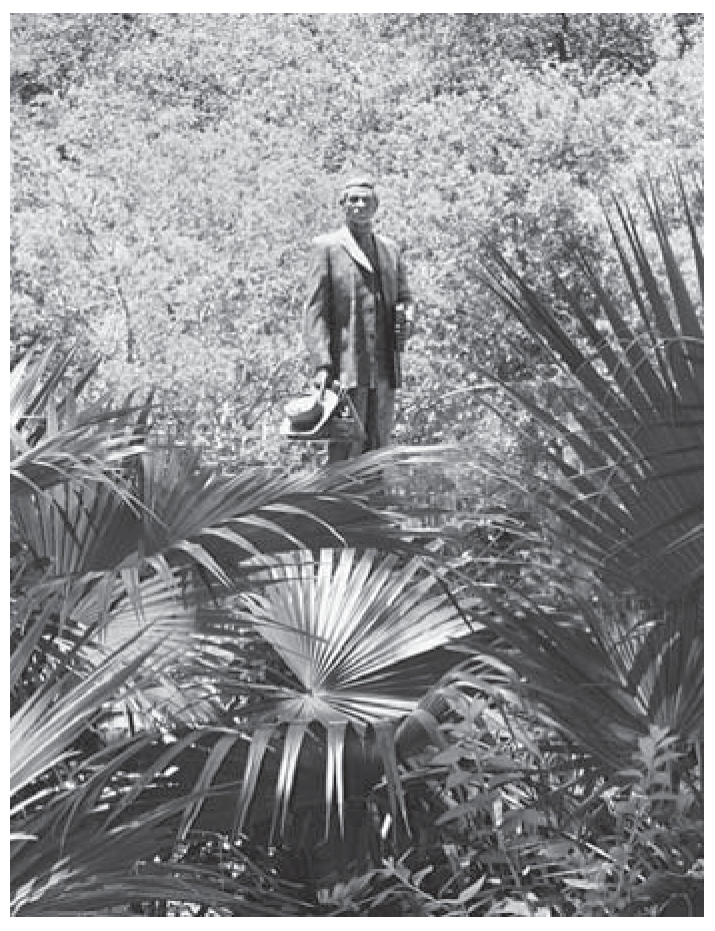

Prevented from erecting a Denmark Vesey monument in Marion Square, black activists installed one in Hampton Park in 2014 after a nearly twenty-year campaign.

Race and politics had always been there, of course, just as they had always been in the garden named for the Redeemer Wade Hampton, where the Martyrs of the Race Course cemetery had once stood. In Hampton Park—as in Marion Square, White Point Garden, and the numerous plantation “gardens” surrounding the city—race and politics had been entangled with the azaleas, live oaks, and crape myrtles for decades, often choking off black memories of the past.

But in the winter of 2014, almost twenty years after Henry Darby conceived his plan, Hampton Park became home to the Denmark Vesey Monument. On February 15, at a ceremony attended by hundreds, the Spirit of Freedom Monument Committee dedicated the memorial in a serene spot located in the center of the park. Executed by Ed Dwight, a black sculptor from Colorado, the monument features a defiant Vesey, standing tall while holding a carpenter’s bag in one hand and a Bible in the other. The text on the base tells the story of Vesey’s life and thwarted insurrection. Frustrated by “his inability to legally free his wife and children,” a new South Carolina law that made the “emancipation of slaves nearly impossible,” and “municipal authorities’ repeated attacks on the AME Church,” Vesey determined that “rebellion was necessary to obtain liberty,” it explains.33

Not long after the monument was installed, Curtis Franks, Avery curator and SFMC member, reflected on its meaning. “It’s one thing for people to say when you look at the African presence in North America, Charleston is a must see.” Yet it was quite another for visitors to search the city in vain for any reminders of the black past, as they had done for decades. Now there was “visible recognition,” Franks noted, of the slave presence in Charleston. Said Bernard Powers, “The monument changes the landscape by now offering a counterpoint to those other monuments to white supremacy . . . that populate Charleston’s streets.”34

By the time that counterpoint went up in 2014, the opposition to the monument had been largely silenced, at least publicly. No one showed up to protest the dedication of the statue, and the city received just a handful of complaints about it. The monument to white Charleston’s great bogeyman failed to generate the animosity that the proposal to build it had elicited even a decade before, for much had happened since then. Charleston was becoming a different city—not easily, to be sure, but different all the same. Nearly one hundred and fifty years after former slaves constructed their short-lived cemetery in Hampton Park to commemorate the martyrs who died fighting to end slavery, the martyr who had haunted Charleston since 1822 was reborn in bronze and stone. Peering through the grove of live oaks that surrounds him, Denmark Vesey now stands watch over his garden.35