ON A SWELTERING JUNE EVENING IN 2015, MEMBERS OF Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Charleston, South Carolina, welcomed a stranger into their weekly Bible study group. For this gesture of Christian fellowship, most of them received a death sentence. After listening quietly for about forty minutes, the visitor—Dylann Roof, a twenty-one-year-old white supremacist who had driven in from nearby Columbia—opened fire inside the venerable black church, killing nine worshippers. Roof then exited through a side door as calmly as he had entered.

Americans soon learned that Roof’s flawed understanding of slavery, among other factors, fueled his racial hatred and his attack. In his online manifesto, he claimed that “historical lies, exaggerations and myths” about how poorly African Americans had been treated under slavery are today being used to justify a black takeover of the United States. Framing himself as a white savior in the tradition of the Ku Klux Klan, he explained during his confession to the FBI that he targeted Charleston because “it’s a historic city, and at one time, it had the highest ratio of black people to white people in the whole country, when we had slavery.”1

In the months before the murders, Roof had made six trips to Charleston and the surrounding area. He later told authorities, “I prepared myself mentally.” During each trip, he visited plantations and other locations associated with slavery, including Emanuel A.M.E. Church. Mother Emanuel, as it is affectionately known, is among the oldest black congregations in the South. It was the church of Denmark Vesey, Charleston’s most famous—and, to some, infamous—black revolutionary. In 1822, Vesey plotted a massive slave uprising for which he and more than thirty co-conspirators were hastily tried and executed. Before Dylann Roof perpetrated his executions two centuries later, he created an archive of his research into Charleston’s enslaved past. In Roof’s car, investigators found travel brochures and several sheets of paper on which the white supremacist had scrawled the names of black churches, Emanuel A.M.E. among them, as well as the name of Denmark Vesey. On his website, Roof had posted a chilling series of photographs. Some showed him at sites he had toured. Others captured him brandishing the Confederate flag. In all of the images, a menacing Roof stares at the camera, his hatred now all too easy to see.2

After the Emanuel massacre, the country looked and felt different. It was as if a veil hiding something disconcerting—an affliction we had been doing our best to ignore—had suddenly been lifted. Behind it sat a toxic mix of beliefs and symbols that, endorsed by some and tolerated by many, came under increased scrutiny. Roof’s support for slavery and the Confederacy that waged war to protect it raised troubling questions about how the country has remembered and commemorated its past. Was it acceptable, for instance, that Confederate statues and flags still enjoyed a prominent place in American culture?

Critics insisted it was not. By late June 2015, New Orleans mayor Mitch Landrieu had asked the city council to take down several monuments, including those honoring Confederate generals Robert E. Lee and P.G.T. Beauregard and the Confederate president, Jefferson Davis. In Tennessee, a bipartisan coalition of lawmakers called for the removal of a bust of Nathan Bedford Forrest, a Confederate general and Ku Klux Klan leader. Critics achieved a major victory on July 9, when South Carolina legislators agreed to remove the Confederate battle flag that had flown at the state capitol since the early 1960s. The effort to purge the country of Confederate and proslavery symbols quickly spread beyond the South, as companies such as Amazon, eBay, Walmart, and Sears prohibited the sale of Confederate flags and similar merchandise from their stores and websites.3

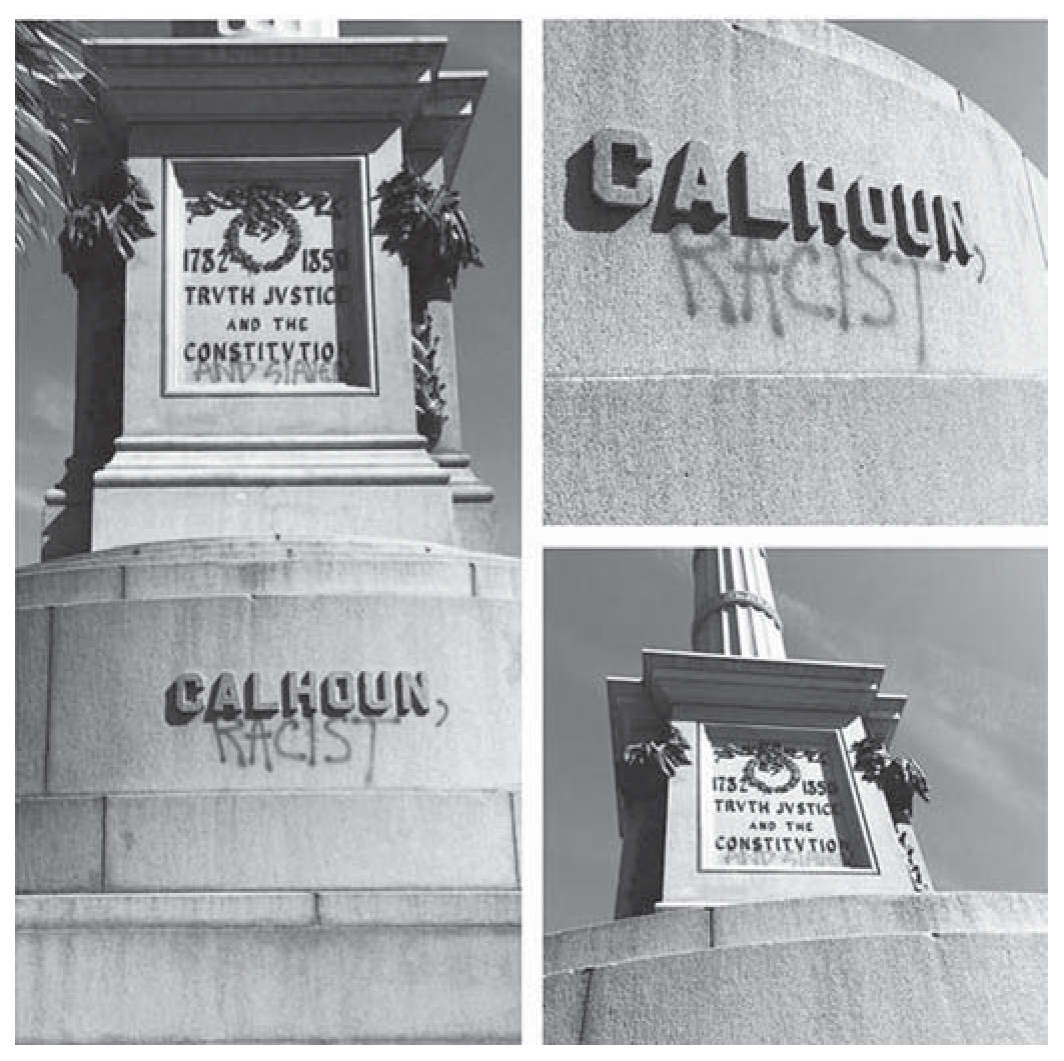

Protesters in ten southern states vandalized statues that honored the Confederacy and those who fought for it. Unsurprisingly, Charleston itself—the site of the church shootings and the birthplace of the Civil War—was an epicenter of this grassroots graffiti campaign. Four days after the Emanuel massacre, vandals struck the Fort Sumter Memorial in White Point Garden, spray-painting the neoclassical paean to the Confederate defenders of the city with the phrases “Black lives matter” and “This is the problem #racist.” Two days later, the towering memorial in Marion Square that honors John C. Calhoun, the South Carolina statesman who famously called southern slavery “a positive good,” was similarly defaced. Protesters painted the word “racist” in red near the base of the tribute. They also modified the monument’s engraved testament, which reads “Truth Justice and the Constitution,” by adding the words “and Slavery.”4

Just days after the Emanuel A.M.E. Church shootings in June 2015, the nearby monument to proslavery statesman John C. Calhoun was vandalized.

The backlash came quickly. In the six months after the Emanuel massacre, tens of thousands of Confederate defenders gathered for more than 350 pro-flag rallies, from Fort Lauderdale, Florida, to Spokane, Washington. One of the largest, in Marion County, Florida, was held to show support for the county’s decision to return a Confederate flag to its government complex. Legislators in several southern states proposed new laws designed to protect Confederate memorials. One Georgia state representative introduced a bill to restore Confederate Memorial Day and Robert E. Lee’s birthday as official state holidays. Accusing detractors of “cultural terrorism,” he compared the effort to remove Confederate symbols to ISIS’s destruction of mosques and temples. “We’re entitled to our heritage,” he stated.5

The decision to take down Confederate statues provoked real terror in some communities. A contractor hired in New Orleans to remove the city’s monuments decided to back out in early 2016 after receiving death threats and finding his car torched by an arsonist. At a 2017 Charlottesville, Virginia, rally in defense of a Robert E. Lee statue slated for removal, a white supremacist plowed his car into a group of counterprotesters, killing one and injuring many. Meanwhile, in Charleston, where the emotional appeal of critics’ arguments would seem to have been the most difficult to resist, Confederate and proslavery symbols remained in place. Calls to remove the Calhoun Monument, located just a block away from Emanuel A.M.E. Church, went nowhere.6

From the cacophony of voices that weighed in on what to do with these flags and monuments—on whether to keep them or take them down—one thing became clear: Americans do not share a common memory of slavery. Some, like Roof, romanticize the institution or deny its centrality to our history. Others focus on its cruelties as an essential component of our national DNA, one that cannot, and should not, be overlooked.

Denmark Vesey’s Garden—the first book to trace the memory of slavery from its abolition in 1865 to the present—offers historical context for this contemporary divide. Since the end of the Civil War more than 150 years ago, generations of whites and blacks in Charleston have forged two competing visions of slavery. On the one hand, former slaveholders, their descendants, and others have promoted a whitewashed memory, one that downplayed or even ignored slavery at times, only to cast it as benevolent and civilizing in other moments. On the other hand, former slaves, their progeny, and some white and black allies have advanced an unvarnished counterpart. They insist that slavery must be recognized and commemorated as a brutal, inhumane institution that has shaped who we are as a nation. The debate sparked in 2015 by the Emanuel massacre, in short, is nothing new.

As the capital of American slavery and a longtime mecca of historical tourism, Charleston provides a better primer for understanding the origins and course of this debate than any other place in the United States. Over the past century and a half, Charleston’s black and white residents, as well as its millions of visitors, have been wrestling with memories of our nation’s original sin. Since the Civil War, Charleston has been teaching us how—and how not—to remember and memorialize slavery.

* * * *

FOR THE TWO of us, the Emanuel massacre gruesomely punctuated our own decade-long reckoning with the memory of slavery. We had embarked on this journey rather unwittingly in the summer of 2005, when we began the process of relocating to Charleston for jobs at the Citadel and the Avery Research Center for African American History and Culture. One June morning, we drove down from Chapel Hill, where we then lived, on a scouting venture. We wanted to rent an apartment downtown, in the heart of what is known as Historic Charleston, and we hoped to find what many people look for when they move to the city: hardwood floors, high ceilings, and exposed brick. That afternoon, we arrived at the first apartment on our list, which turned out to be the bottom floor of a beautiful antebellum home flanked by spacious verandas and white columns. The owner answered the door and invited us inside the basement apartment, which, updated with gleaming granite countertops and custom window treatments, appeared ready for an Architectural Digest photo shoot. As she ushered us through the rooms, we made small talk, asking about the home’s construction and its previous owners.

Like many Charlestonians who spend their days surrounded by relics of the past, our prospective landlady had done her research—sort of. The house had been built around 1840 by the Toomers, a wealthy family that included two physicians. Up until the Civil War, she informed us, the apartment we were considering had been the workspace of the servants. “Of the slaves,” one of us instinctively replied. The home owner again insisted they were servants. “There’s no evidence in the historical records,” she explained, “that the Toomers didn’t pay them.” It was quite a double negative. As we suspected that day and later confirmed, enslaved people in fact lived and worked in the Toomer household.7

The apartment was not for us. We found a slightly more ramshackle unit that was a better fit. (By sheer coincidence, our new home was located just half a block from where Denmark Vesey’s house had once stood.) But the exchange that June day proved pivotal. Even though we moved to California after only two years in Charleston, we spent the next decade exploring how white residents like the owner of the Toomer house could be oblivious to the role of slavery in their city’s history. This book results from our experiences there, from the fact that many of the white Charlestonians we encountered did not want to acknowledge slavery at all, and from the fact that when they did they often mischaracterized it as benign, even beneficial. Put another way, this book stems from our belief that the unvarnished tradition of remembering—which has long competed with the whitewashed tradition, though rarely on equal ground—is superior.

Admittedly, this motivation carries the taint of judgment. Scholars of historical memory tend to focus more on how individuals and groups use memories of the past for particular purposes than on the truthfulness of those memories. They home in, in other words, on the function of historical memory rather than on its accuracy. In the pages that follow, we are very much attuned to the function of memory. We explore how Charlestonians invoked and constructed recollections of slavery for political ends—some reactionary, some progressive. We also examine how they filtered the events of their lives through stories of the institution passed down from years or even decades before. Still, this book in an important sense represents a rejection of historical inaccuracy, a rejection of whitewashed memories of slavery. Being clear on this point matters because we should strive to get the past right. But it also matters precisely because of how whitewashed memories have been used in modern America. It does not take a massacre in a black church to see that the way we remember slavery has serious implications for race relations today.8

The United States is overdue for an honest conversation about slavery, however much that conversation may be unsettling to the descendants of slaveholders or painful to the descendants of the enslaved. Charleston’s long struggle over the memory of slavery can help us understand how that conversation should proceed.

* * * *

CHARLESTON WAS THE capital of American slavery. Nearly half the slaves transported for sale in this country first set foot on North American soil in Charleston or on neighboring Sea Islands. The city also had a vibrant market for slaves traded locally, as well as for those sold down the river to the cotton and sugar plantations of the Deep South. The enslaved people who toiled in Charleston and the surrounding Low-country made the region’s planters among the richest men in America by the end of the eighteenth century, ensuring that they would resist any attempt to limit or abolish slavery. It was South Carolina statesmen who stymied efforts to outlaw the transatlantic slave trade at the Constitutional Convention in 1787 and who led the fight against the antislavery movement in the nineteenth century. By 1860, Charleston had become the hotbed of secessionism, a place dedicated at all costs to maintaining slavery. That defense culminated in the firing on Fort Sumter, the opening salvo of the Civil War. Charleston would never have emerged as the Cradle of the Confederacy, as it has often been called, had it not also been the capital of slavery.9

Charleston, moreover, is a city where people have long traveled to learn about America’s past. If Philadelphia and Boston serve as the clearest windows into our nation’s colonial and Revolutionary-era history, Charleston is the best portal to the antebellum South. It is where the Old South reached its apotheosis and met its demise, a place where the physical reminders of days gone by—antiquated buildings, forts, and plantations—are abundant and well preserved. Since the 1920s, the city has waged a sophisticated campaign to market its historical treasures and frame itself as America’s Most Historic City. With just over 100,000 residents, Charleston attracts more than five million visitors a year and has been named the number one small American city for tourists by Condé Nast six years in a row. The entire city is a living history museum. No place in America has spent as much time and energy selling memories—most whitewashed, others unvarnished—of its past.10

Charleston, then, presents an unrivaled opportunity to study how slavery has been remembered. Indeed, the potency of Charleston as a place of remembrance is no better illustrated than by Dylann Roof himself. Roof set his sights on Charleston because on some level he recognized that it was the capital of American slavery and a mecca of historical tourism. As he prepared himself for the shootings, he played the part of tourist. Roof visited the restored slave cabins at the plantation museums that surround the city, as well as the site of the pest house on Sullivan’s Island, where some victims of the transatlantic slave trade were quarantined. He even chose the location of his attack—Emanuel A.M.E., Denmark Vesey’s church—with the memory of slavery in mind. After the thwarted slave insurrection and the hanging of Vesey and his co-conspirators, the church was torn down, only to be rebuilt after emancipation. Mother Emanuel emerged from the ashes of the Civil War as the most significant black church in South Carolina. Its most well-known member, meanwhile, haunted the dreams of white Charlestonians for generations.11

Charleston also allows us to explore the long history of the memory of slavery. Memories of the “peculiar institution,” the southern euphemism for slavery coined in the 1830s by John C. Calhoun, hung over Low-country South Carolina well after emancipation, even when some people attempted to ignore them. Competing recollections of slavery influenced the political debates that roiled Charleston during the 1860s and 1870s, when the city—and the state of South Carolina more generally—was ground zero for the project of Reconstruction. In the decades that followed, Charleston created a tourism industry concerned almost entirely with marketing its history. And within the city and beyond, on the isolated Sea Islands that lay nearby, black remembrances of slavery took root and thrived, surviving the stultifying atmosphere of segregation to become a major source of power during the civil rights movement.12

Charleston and the surrounding environs thus enable us to link together a larger narrative usually told only in parts. This extended view yields significant insights. For example, while a whitewashed vision of slavery that softened the institution’s cruelties and downplayed its role in causing the Civil War reigned in Charleston for much of the twentieth century, it did not dominate in the aftermath of the conflict. On the contrary, black Charlestonians and their white Republican allies controlled the public memory of slavery in the city in the late 1860s and 1870s. Black memory is sometimes seen as countermemory, but as the case of Charleston shows, white remembrances, not black, existed on the sidelines in the wake of the Civil War.13

Charleston, too, offers an unusually clear window into the genealogy of social memory. It reveals how personal memories of the past coalesced into collective, social memory—the aggregation of individual remembrances. Neither white nor black Charlestonians could easily forget slavery, though some certainly tried. By virtue of their intimate ties to slavery and their self-conscious approach to interpreting and preserving their past, individual Charlestonians were prolific memory makers. A small group of white writers and editors, to take one example, promoted a Lost Cause narrative that celebrated the Confederacy and disassociated it from slavery—a narrative they helped spread across the country. To take another, the way in which memory was mapped onto Charleston’s public landscape as the city became a tourism hub owed much to one white woman steeped in family remembrances that dated back to the colonial era.14

Tracing the genealogy of black social memory is not as easy, particularly after the turn of the twentieth century, when segregation forced the retreat of individual memories into the shelter of homes, schools, and churches. But it is possible, and there are parallels between the histories of white and black memories of slavery in the city. When African American tour guides succeeded in diversifying Charleston’s tourism industry in the 1980s, for instance, they, too, drew on stories of slavery handed down from family and friends, forging a newly available collective memory for locals and tourists alike.

Finally, although focused on one Deep South city, the story we tell is a national one with national players. Since 1865, Charlestonians’ memory work has been the product of ongoing interaction between locals and outsiders, between the city and the rest of the country. To be sure, Charleston would seem nothing if not a provincial backwater throughout the late nineteenth and much of the twentieth centuries. For one, the city continued to support a recalcitrant southern politics long after the Civil War. It was also isolated, a remote coastal port that was difficult to reach until better roads constructed after World War I facilitated automobile access.

But for many non-natives, Charleston’s refusal to join the modern world proved immensely appealing. Some, like Frank Dawson, an Englishman who fought for the Confederacy, made Charleston their adopted home. Moving to the city in 1866, Dawson played a profound role in shaping memories of slavery in his capacity as editor of the Charleston News and Courier. Others—like the curious northern tourists who traveled to Charleston to take in its crumbling mansions and scenic plantations—inquired about the history of the peculiar institution in ways that forced local whites to remember it, if on their own terms. One of the most significant efforts to preserve black memories of slavery in Charleston originated with the federal government. The slave narrative program of the Federal Writers’ Project resulted from a delicate negotiation between former slaves, local interviewers, and staff at the offices in Charleston, Columbia, and Washington, D.C. While Charleston offered uniquely fertile ground in which memories of slavery could grow, those memories were nurtured by a variety of constituencies, many of whom were not native to the city. As Charleston reminds us, historical memory in the South, and about the South, is not exclusively southern.

This truth has been illustrated time and again since June 2015. Dylann Roof committed the Emanuel massacre in Charleston, and yet the entire nation has since debated how best to remember slavery because the issue has never been—and cannot be—confined within the borders of the South. Since the end of the Civil War, southern memory-making has been American memory-making. The Lost Cause tradition may have been forged in places like Charleston, but its influence extended north and west of the Mason-Dixon Line and persists to this day, even in California’s Central Valley, where we now live. Fearful of jeopardizing sales to southern school districts, American publishers have for decades produced middle and high school textbooks that muddy the waters on what caused the Civil War. Despite modern historians’ near unanimous agreement that slavery was the central cause of the conflict, these works have taught generations of students that other issues—such as states’ rights, tariffs, even the use of public lands—had as much, if not more, to do with sending southern boys off to war as did slavery.15

Opinion polls demonstrate the consequences of these lessons. As the United States began the 150th anniversary commemoration of the Civil War in 2011, the Pew Research Center found that 48 percent of Americans believed that the issue of states’ rights was the cause of the conflict. Only 38 percent attributed the war primarily to slavery. Among Americans aged thirty and younger, 60 percent stated that states’ rights explained the war—the highest among any age group and a worrisome statistic for the future. The enduring misunderstanding of our nation’s pivotal conflict is more common in the South, certainly, but it afflicts residents in every region of the country. Other polls reveal that a broad swath of Americans is ignorant of, or indifferent to, the horrors of slavery. According to a New York Times analysis of a poll from early 2016, nearly 20 percent of Donald Trump supporters objected to Abraham Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation, which declared the vast majority of American slaves free. Though tempting, portraying southern proponents of the whitewashed memory of slavery as outliers is mistaken.16

Denmark Vesey’s Garden, in sum, tells a local story with national relevance. Charleston’s long fight over how slavery should be remembered—as an incidental but comforting fairy tale of faithful slaves and doting masters, or as a shocking nightmare that lies at the core of our national identity—provides an unparalleled window into a conversation that involves all Americans. And, as we have seen, it is a conversation that is far from over.