“IF THERE BE A TOWN IN THE UNITED STATES, WHICH might be regarded as the citadel and capital of American slavery,” wrote New England abolitionist Elihu Burritt in 1851, “that town is Charleston, in South Carolina.” Burritt was right. No American city rivaled Charleston in terms of the role that slavery played in its formation and success, nor in the political, economic, and ideological support it provided for the expansion of slavery in the United States. And no American city better illustrates the brutal realities of human bondage, realities that belie the whitewashed image of the peculiar institution crafted by its Old South and latter-day apologists.1

Settled by the English in 1670, Charleston was the metropolis of South Carolina—the first British North American colony to hold the dubious honor of being a slave society from its beginning. While older southern colonies, such as Virginia and Maryland, took decades to embrace slavery wholeheartedly, South Carolina’s white founders—many of whom came from Barbados, where the institution was essential to the thriving sugar industry—relied upon bound black labor at the outset. Just one year after the colony was founded, a Native American reported that “the settlement grows . . . the castle is getting bigger, [and] many Negroes have come to work.” By the middle of the 1670s, one in four Charlestonians was enslaved.2

The city’s black population surged upward in the eighteenth century. From the early 1700s to the 1850s, African Americans constituted a majority of Charleston residents, making it unlike any other major North American city. In terms of racial composition and hierarchy, Charleston more closely resembled the slave ports of the Caribbean than it did its neighbors to the north. A white minority sat atop the pyramid, while a broad base of slaves formed the bottom. In the middle was the free black community, a small sliver that included a mulatto elite. Often called “browns,” this elite group had close ties to planters and counted some slaveholders in its ranks.3

At the start of the American Revolution, Charleston had almost 6,000 slaves, more than Boston, New York, and Philadelphia combined. The surrounding Sea Islands and Lowcountry—so named for a flat topography that an early colonist compared to a “Bowling ally”—had an even higher proportion of enslaved residents. Walking the streets of colonial Charleston, which grew into the fourth-largest city in British North America by the mid-eighteenth century, one could hear any number of European and African tongues as well as Gullah, the distinctive hybrid language developed by slaves on isolated, coastal plantations.4

In the mind’s eye of white Carolinians, the city’s black population could seem overwhelming. Some imagined black-to-white ratios of fifteen or even twenty to one. Visitors were also struck by the Lowcountry’s distinctive demography. “At my first coming to this Province,” a European tourist wrote to the South Carolina Gazette in 1772, “I was not a little surprised at the Number of Black Faces that every where presented themselves.” The anonymous author’s surprise only grew when he reached Charleston, which, he suggested, could easily be confused for “Africa, or Lucifer’s Court.” Eighty years later, in the early 1850s, Scandinavian Fredrika Bremer wrote that “Negroes swarm in the streets.”5

Black faces swarmed those streets because of the region’s dependence on white rice. After experimenting with other commodities, including tar, pitch, turpentine, and deerskins, early South Carolina settlers determined that rice was the key to their economic future. Drawing on West African slaves’ knowledge of rice cultivation, planters began draining, damming, and irrigating Lowcountry bogs and marshes, which proved well suited to the profitable grain. Building rice plantations without modern machinery, however, was a grueling endeavor, which was only made worse by the heat, humidity, and disease of South Carolina’s “funereal lowlands,” as one scholar has aptly dubbed them. Still, rice promised remarkable riches to planters who could find the requisite workforce. Unable to entice enough English indentured servants, or to subdue enough Native Americans, to build their burgeoning rice empire, white Carolinians turned to African forced labor. “Here is no living . . . without” slaves, observed a colonist in 1711.6

Smith’s Plantation, Beaufort, South Carolina, ca. 1862. Enslaved people greatly outnumbered free people in the Lowcountry.

By the middle of the eighteenth century, the city sitting at the confluence of the Ashley and Cooper rivers was a central node in a thriving British slave trade that brought more than three million Africans to New World colonies between the mid-1600s and early 1800s. Charleston was British North America’s leading destination for slaves who were transported from Africa and the West Indies. Between 1670 and 1808, nearly two hundred thousand slaves—approximately half of the bondpeople who disembarked in what became the United States—were imported through the city. Boasting the largest port in the lower South, Charleston enjoyed a veritable monopoly on the slave trade between the Chesapeake and St. Augustine, Florida. Buyers came from more than one hundred miles away to bid on the enslaved men, women, and children who were auctioned off aboard ships in the harbor, in city taverns, and at the wharves that surrounded the peninsula. Slave sales on or near Gadsden’s Wharf, which dominated traffic after it opened in 1773, were held six days a week.7

Many of these forced migrants and their offspring ended up on sprawling coastal plantations. Their masters often retreated from their countryside estates to urban refuges like Charleston, leaving the backbreaking and at times deadly work of growing rice to their black laborers and overseers. This led to the development of the task system, in which the enslaved had to complete a specific task—say, planting a quarter acre of rice—each day. Once they were finished, whatever portion of the day remained was their own. Planter absenteeism, geographic isolation, and the regular infusion of new slaves contributed to a greater degree of African cultural retention in the Lowcountry than in other North American slave societies. The most obvious example of this phenomenon was the emergence of Gullah—the syncretic language and culture that coastal South Carolina slaves crafted from African and New World elements.8

The uncompensated labor of Lowcountry slaves turned South Carolina into “the most opulent and flourishing colony on the British continent of North America,” as Robert Pringle, a prominent judge, merchant, and slave trader, put it. By the late eighteenth century, South Carolina was the leading rice supplier for Europe and the Americas, its enslaved workers filling empty bellies from Rotterdam to Rio de Janeiro and the pockets of planters throughout the Lowcountry. Enterprising slaveholders supplemented their incomes by growing indigo, a valuable and complementary crop to rice, which enabled them to more fully use their land and abuse their overtaxed workforce. Meanwhile, the transatlantic slave trade made Charleston merchants, including Henry Laurens, Gabriel Manigault, Miles Brewton, and Robert Pringle, among the wealthiest residents in the original thirteen colonies.9

On the eve of the American Revolution, stately homes lined Charleston’s unpaved streets. In 1773, Bostonian Josiah Quincy dined at Miles Brewton’s new residence, a King Street double house that today is a staple destination on tours of Historic Charleston. It has “the grandest hall I ever beheld,” gushed Quincy in his journal. “Azure blue satin window curtains, rich blue paper with gilt . . . most elegant pictures, excessive grand and costly looking glasses etc.” While South Carolina also had poor and working-class residents in addition to its enslaved majority, economic analysis confirms local boasts: by the 1770s, slavery had made the Lowcountry one of the wealthiest regions in the world.10

Little wonder that white South Carolinians led the fight against the antislavery impulse unleashed by the Revolution. The Enlightenment ideals of liberty and equality, combined with a boycott of commerce with Great Britain, undermined slavery in the late eighteenth century, contributing to its abolition in northern states and the temporary suspension of the foreign slave trade across the fledgling nation, including in South Carolina. But the state’s compliance with the Continental embargo on slaves (and everything else) did not reflect fundamental misgivings about slavery or human trafficking. Indeed, South Carolina elites brooked no challenge to their right to buy, sell, or own human beings. When Thomas Jefferson included a passage blaming King George III for the slave trade in a draft of the Declaration of Independence in 1776, South Carolina and Georgia statesmen compelled him to remove it. A decade later, South Carolina’s delegation to the 1787 Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia bluffed its way into prolonging the transatlantic slave trade for two decades. “If the Convention thinks that North Carolina, South Carolina, and Georgia will ever agree to the plan, unless their right to import slaves be untouched,” declared Charlestonian John Rutledge, “the expectation is vain.” Fearful that these southern states—especially South Carolina and Georgia—would not join the new nation if the Constitution empowered the federal government to move immediately against the slave trade, the convention prevented Congress from prohibiting it until 1808.11

Rutledge and his fellow South Carolina delegates thus paved the way for the importation of perhaps seventy thousand more African captives through Charleston as well as for the geographic and economic expansion of slavery in the United States—all after the American Revolution. Fears of slave insurrection, among other factors, had led South Carolina lawmakers to close the transatlantic slave trade to the state between 1787 until 1802. But after Eli Whitney’s cotton gin made short-staple cotton wildly profitable, planters from the northwestern portion of the state, called the Upcountry, began clamoring for slaves. They succeeded in reopening the trade in 1803. Over the next five years, slave ships poured into and out of Charleston, providing enslaved laborers to secondary markets like Georgetown as well as to inland plantations in South Carolina, Georgia, and beyond. As a British visitor observed in 1807, “Thousands of these miserable people are dispersed over the adjoining states, through the port of Charleston, where there is a greater slave-market than, perhaps, was ever known at one place in the West India islands.” Combined with Whitney’s invention, this great slave market pushed enslaved laborers and the cotton plants they tended steadily westward—from Upcountry South Carolina and Georgia to new states, including Alabama, Mississippi, Louisiana, and, eventually, Texas. Charleston helped make cotton king and the Deep South slave country.12

Although the transatlantic slave trade was abolished in 1808, antebellum Charleston served as a vital center of the internal American slave trade through the Civil War. Some two million enslaved people were bought and sold in the United States between 1820 and 1860. The majority of these sales were to local buyers, but more than 600,000 were interstate transactions, many of which resulted in slaves being separated for good from their homes, friends, and family. Few cities—perhaps only Richmond, Virginia—rivaled Charleston as an exporter of enslaved laborers to the emerging Deep South’s cotton empire. By the 1850s, the city boasted more than thirty slave-trading firms and many more slave-dealing brokers, auctioneers, and commission agents—euphemisms locals preferred to the more accurate “negro-trader.” The sale of Charleston slaves to the Old Southwest was so robust in the years leading up to the Civil War, in fact, that by 1860 white residents outnumbered black for the first time since before the Revolution.13

Charleston’s domestic slave trade was concentrated in the heart of the city, a stone’s throw from City Hall, St. Michael’s Church, and the offices of both the Charleston Courier and the Charleston Mercury. While private sales typically took place in brokers’ offices near Adger’s Wharf and on Broad, State, and Chalmers streets, most public auctions in the antebellum period were held just north of the Exchange Building, which was home at various times to the city hall, the custom house, and the post office. Outside this well-trafficked East Bay location, humdrum municipal and commercial routines intersected with the most tragic of transactions: the sale of human flesh. New England missionary Jeremiah Evarts witnessed one such spectacle on March 13, 1818, when 105 slaves of the recently deceased Colonel John Glaze were auctioned off to the highest bidder. As the men, women, and children took turns mounting a large table to be examined by the crowd, they appeared to Evarts to be “exceedingly disconsolate, much as if they were led to execution.” Awaiting their fate at the auction block, the human chattel sat on a razor’s edge: Would their new master be kind or cruel? Would they be sold away from their loved ones? Some sales brought relief, even glimmers of joy. Others left the enslaved venting their “grief, rage, indignation, and despair” through “tears and broken sentences.” Three decades later, in 1853, a European visitor wrote that watching a slave sale outside the Exchange made his “hair stand on end.” Grown men wept like infants as they were separated from their wives. Children clung in vain to their mothers’ dresses.14

British artist Eyre Crowe’s sketch of a slave sale outside the Exchange Building, published in the Illustrated London News, November 29, 1856.

The visibility of these heart-wrenching scenes caused much consternation in Charleston, for they exposed slavery’s unseemly underbelly to anyone who came to town. In the late 1830s and early 1840s, city officials passed multiple ordinances to regulate the trade, including a measure that prohibited the sale of slaves in public spaces. Yet slave brokers routinely ignored this prohibition without consequence, and in 1848 they convinced the city council to repeal it. Still, worries about the open sale of slaves persisted. So, too, did the traffic jams produced by crowds that regularly spilled over into East Bay Street during auctions at the Exchange. In 1856, Charleston passed an ordinance that outlawed the public sale of slaves, among other commodities, in the area around the Exchange Building. The new interdiction sparked strong opposition from the mayor, who worried that it was a concession to “mawkish and false sentiment as to the publicity of slave sales.” A group of slave traders, led by Louis DeSaussure, Alonzo J. White, and Ziba B. Oakes, denounced the measure as an impolitic admission that would give “strength to the opponents of slavery” and “create among some portions of the community a doubt as to the moral right of slavery itself.” Yet the law was maintained, and starting July 1, 1856, slave auctions took place behind closed doors in nearby slave-trading offices and marts, the most prominent of which was a large complex between Queen and Chalmers streets called Ryan’s Mart.15

Charleston was more than just a hub of human trafficking. It was also the epicenter of social and cultural life for South Carolina planters, whether they grew rice in the Lowcountry or cotton in the Upcountry. The closest thing in the United States to European nobility, these elite slaveholders were preoccupied with manners and ancestral pedigree, flaunting their wealth despite the misery around them. Each January, planter families and their domestic slaves descended on Charleston for a season of balls, concerts, and horse races that lasted through March. Extravagant parties, many held just blocks away from the slave auctions at the Exchange and Ryan’s Mart, provided diversion during the winter social season. In 1851, Emma Clara Pringle Alston entertained two hundred guests, who dined on four turkeys, four hams, sixty partridges, ten quarts of oysters, and dozens of cakes, creams, and jellies. These migrating entourages returned to their Charleston homes again during the summer months, trading the malarial swampland for the port city’s cooling sea breezes.16

Few Charlestonians could match Emma Alston’s lavish offerings or the enslaved manpower that made them possible. But the widespread dispersal of slaveholding in the city—three out of every four white families owned at least one slave in the mid-1800s—meant that most white residents had a slave to wait on, or earn money for, them. It also meant, however, that most white residents interacted on a daily basis with someone who had every reason to despise them or even wish them dead.17

The fear of slave insurrection plagued the Old South and gave nightmares to white residents of Lowcountry South Carolina, with its black majority. Local authorities responded by cracking down after slave revolts, whether realized, imagined, or foiled at the last minute. The bloody 1739 Stono Rebellion, which began southwest of Charleston, was frighteningly real. More than sixty people (white and black) died, and as a result the state passed new laws that limited manumission and called for greater surveillance and stricter discipline of the enslaved.18

Eighty years later, in 1822, news that another slave uprising was in the works again rocked Charleston. The mastermind behind this plot was Denmark Vesey, a black carpenter and former slave who had purchased his freedom with winnings from the city lottery but was unable to do the same for his family members. Vesey and several of his co-conspirators were class leaders at the recently established African Church, the African Methodist Episcopal congregation that became Mother Emanuel after the Civil War. More than four thousand African Americans worshipped at the large church built at the corner of Reid and Hanover streets in the Hampstead neighborhood, or at several missionary branches. Charleston officials viewed this independent African Church as a threat to their authority and repeatedly harassed its members. Infuriated by these attacks and unwilling to live any longer under this repressive regime, Vesey and his colleagues formulated a plan for a large-scale insurrection. On July 14, Bastille Day, slaves and free blacks from across Charleston and the surrounding plantations were to rise up, attack white masters, and then set sail for freedom in Haiti. But the rebellion was foiled before it could be carried out, and local authorities arrested 131 slaves and free blacks, torturing many of them. Ultimately, Charleston executed Vesey and thirty-four co-conspirators and sold a similar number, including Vesey’s son Sandy, outside the United States.19

In the aftermath of the affair, white South Carolinians tore down the African Church’s house of worship, curtailed the few liberties afforded free blacks, and tightened slave supervision. To bolster the City Guard that policed Charleston, the state appropriated funds to support a permanent Municipal Guard of 150 men and authorized the construction of “a Citadel” that would house the new guardsmen and their weapons. In 1830, the Citadel, which sat between Meeting and King streets on the northern outskirts of town, opened its doors. Manned first by a detachment of U.S. soldiers and later by members of the state militia, this well-fortified brick structure became home to the cadets of the South Carolina Military Academy in 1843.20

The Work House, where slaves were imprisoned and tortured, in 1886. Damaged by a massive earthquake that year, the building was torn down in 1887.

The Citadel was just one part of the city’s elaborate architecture of racial control. At the corner of Meeting and Broad streets, across from City Hall and St. Michael’s Church, sat the Guard House. After it was remodeled in the late 1830s, this hulking building featured enormous Doric colonnades that projected out into a sidewalk at the very center of the city. The Guard House was the headquarters of the City Guard, whose daily patrols were, like the Guard House itself, an ever-present reminder to slaves that they were being watched. Farther up the peninsula, the Picquet Guard House at the Citadel Green, the parade ground adjacent to the Citadel, served as the headquarters for the guardsmen who monitored northern neighborhoods.21

Near the center of the city, on Wentworth Street between Meeting and King streets, was Military Hall, an imposing Gothic structure built in the 1840s in which Charleston’s militia companies gathered to meet, drink, feast, and, on occasion, drill. Just a few blocks away from Military Hall, on the corner of Magazine and Mazyck streets, was the even more ominous Work House, where many of those accused in the Vesey conspiracy trials had been tortured. Standing just to the east of the District Jail, the Work House was a house of corrections for slaves. Once located in an old sugar refinery, the Sugar House, as the Work House was popularly known by the nineteenth century, held enslaved people arrested by the City Guard as well as those sent by their masters to get “a bit of sugar” for a small fee. After visiting Charleston in the 1850s, antislavery reporter James Redpath compared the Work House to “a feudal castle in its external form.” But “in its internal management,” Redpath added, the Work House resembled “the infamous Bastille or the Spanish Inquisition.” It “is destined to be levelled [sic] to the earth amid the savage yells of insurgent negroes and the shrieks of widowed ladies,” he predicted. The building was outfitted with whipping posts and a treadmill that used human steps to grind corn, an instrument of torture that kept twenty-four black men and women plodding eight hours a day on two enormous wheels. With its victims’ arms shackled to an overhead rail and a driver who whipped those who fell behind with a cowhide, the Work House treadmill inspired greater fear than a flogging.22

Private citizens supplemented Charleston’s racial architecture. Planters surrounded their property with high walls and other barriers designed to keep human property in and trespassers out. A former slave recalled that the owner of one mansion placed broken bottles atop the surrounding wall so as “to inflict mortal injury on any who attempted to climb into the inclosure [sic].” Others topped fences and walls with systems of defensive metal spikes called chevaux-de-frise. While strolling down lower Meeting Street in November 1818, New England minister Abiel Abbot noticed several luxurious homes that “were fortified by lofty iron railings & a horizontal bar of great strength, stuck close with sharp spikes of a foot in length.” A few years later, chevaux-de-frise were added to the fence in front of the Miles Brewton House that had so impressed Josiah Quincy.23

In the decades after Vesey’s failed revolt, the City Guard monitored Charleston on foot and horseback, day and night. By the 1850s, the City Guard had grown to more than 250 men. Visitors often remarked on its ubiquitous presence, as well as on the strict observance of the city’s nightly curfew. “Among my first impressions of Charleston,” wrote a northerner in the early 1830s, was “the sense of insecurity on the part of its inhabitants. . . . The police were in military uniform, and one of these seeming soldiers was stationed in the porch of each church during the time of service. At evening, close following a sweet chime from St. Michael’s, resounded the drum-beat, signal to the black population that they must no longer be found abroad.” The city extended the reach of its police force in the early 1850s, when it annexed the Charleston Neck. This poor neighborhood north of Calhoun Street, which was the residence of many free blacks as well as a number of slaves who lived apart from their owners, already had its own police force and guardhouse, which included a workhouse outfitted with a treadmill. Changing the name of the Charleston Neck to the Upper Wards, the city council consolidated the Neck guard with its own and assumed management of the newly dubbed Upper Wards Guard House.24

Charleston also tracked slaves who were hired out by their masters by imposing the nation’s only slave badge system. Dating back to the earliest days of the colony, the practice of slave hiring enabled masters to earn wages from their human property, whether they were domestics, unskilled laborers, or skilled craftsmen, while conceding to the enslaved greater autonomy over their working and living arrangements. Some slaves were even permitted to hire themselves out, a frowned upon but not uncommon practice. To better monitor hired-out laborers, Charleston officials passed laws that required hired-out slaves (and for a brief time free blacks) to carry a ticket or, more often, a metal badge issued by the city. Hired-out slaves were expected to wear their badges in a visible place or, in the case of house servants, be able to present them upon demand.25

Defending slavery necessitated more than just keeping a watchful eye on the city’s enslaved population; it also required a resolute effort to mitigate external threats. After the Vesey conspiracy, South Carolina passed the Negro Seamen Act, which called for any free black sailors on ships that docked in Charleston Harbor to be imprisoned for the duration of their stay, lest they corrupt enslaved residents with subversive ideas. A decade later, South Carolina supporters of Vice President John C. Calhoun’s theory of nullification came close to sparking armed conflict with the federal government in an effort to forestall future challenges to slavery. Nominally, the Nullification Crisis concerned the tariffs of 1828 and 1832, both of which the state’s cotton and especially rice planters found onerous. At its base, however, the South Carolina Nullification Convention’s decision to declare the two tariffs unconstitutional and unenforceable in the state after February 1, 1833, was an attempt to check federal power that might eventually be aimed directly at slavery.26

“I consider the Tariff, but as the occasion, rather than the real cause of the present unhappy state of things,” Calhoun had admitted to a northern friend in 1830. “The truth can no longer be disguised, that the peculiar domestick institutions of the Southern States, and the consequent direction which that and her soil and climate have given to her industry, has placed them in regard to taxation and appropriation in opposite relation to the majority of the Union.” If slaveholding states did not have the power to nullify federal laws, they would be forced to either rebel against federal authority “or submit to have . . . their domestick institutions exhausted . . . and themselves & children reduced to wretchedness.” The nullifiers’ gambit failed after other southern states refused to rally alongside South Carolina. Yet the Nullification Crisis did help to unify the state behind Calhoun and his even more extremist allies, undercutting the voices of Unionism and moderation when it came to slavery.27

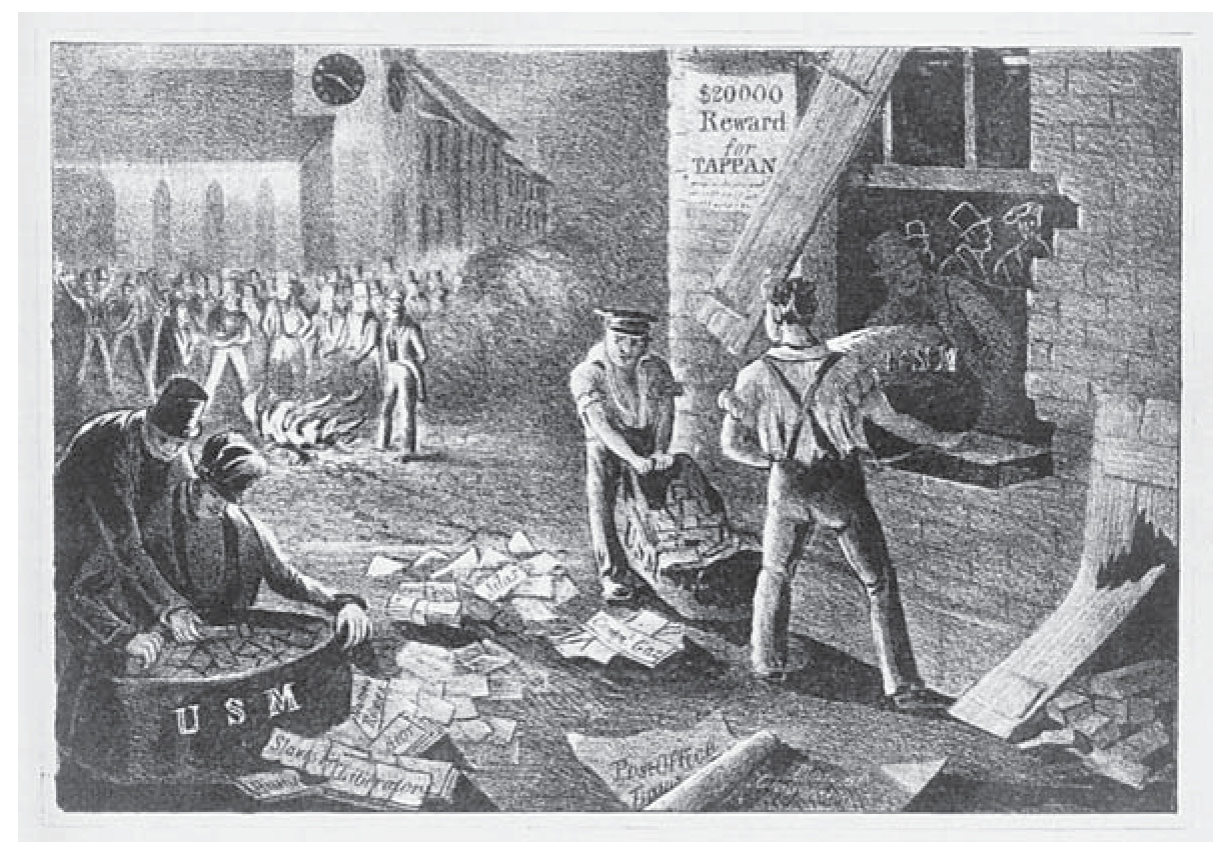

Two years later, white Charlestonians led the South in its radical response to an equally radical movement that was burgeoning up north. Rejecting the moderate solutions of previous generations of abolitionists—gradual emancipation, African colonization, compensation for slaveholders—a biracial coalition of northern reformers led by William Lloyd Garrison set out in the early 1830s to convince the nation that a sin like slavery must be abandoned immediately and without any thought to recompense for masters. Garrison’s American Anti-Slavery Society printed one million antislavery tracts, many of which they mailed to prominent whites in the South. When a shipment of these pamphlets arrived in Charleston on July 29, 1835, members of a vigilante group called the Lynch Men broke into the post office and seized them. The following evening, several thousand Charlestonians gathered at the Citadel Green to watch the Lynch Men burn the tracts as well as effigies of Garrison and other prominent abolitionists in an enormous bonfire. In the week that followed, Charleston officials responded as if the city were under siege. They appointed a special committee that suspended free black schools, redoubled City Guard patrols, and made sure that no “incendiary” mail was delivered. Eventually, President Andrew Jackson and his postmaster general effectively sanctioned Charleston’s response, implementing a policy that permitted southern postmasters to refuse to deliver abolitionist mail—arguably “the largest peacetime violation of civil liberty in U.S. history,” according to historian Daniel Walker Howe.28

In July 1835, a white mob raided the Charleston post office and stole abolitionist pamphlets, which they torched in a bonfire on the Citadel Green.

Charlestonians did not stop there. As northern antislavery critiques grew louder in the late 1830s and 1840s, elite residents curtailed their practice of sending their sons to New England universities, where they might be “tainted with Abolitionism.” By this point, the city’s myriad newspapers and periodicals dared not print a negative word about slavery. “Among all these publications, whether quarterly, monthly, weekly, or daily,” declared a British travel writer in 1842, “there is not one that ever ventures to speak of slavery as an institution to be condemned, or even regretted. They are all either indulgent towards, or openly advocates of, this state of bondage.” A decade later, Robert Bunch, the newly arrived British consul in Charleston, reported back to his superior in London that “it is most difficult for anyone not on the spot to form an adequate idea of the extreme sensitiveness and captious irritability of all classes of this community on the subject of Slavery.” It was “the very blood of their veins.”29

With slavery coursing through the bodies of their constituents, South Carolina statesmen did everything they could to inoculate against the abolitionist contagion. In response to a flood of antislavery petitions to Congress in the mid-1830s, James Henry Hammond, a congressman and planter from the Upcountry, formulated a “gag rule” by which the House of Representatives declined to receive any petition that addressed slavery. Hammond’s Upcountry ally John C. Calhoun proposed a similar measure in the Senate. In the end, both the House and the Senate adopted modified versions of the South Carolinians’ gag rules, which prevented the discussion of antislavery petitions in Congress for nearly a decade.30

Calhoun and Hammond saw no reason to apologize for slavery as southern politicians, including George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, and James Madison, had done for decades. Instead, they trumpeted slavery as a benevolent system that should be celebrated. “Every plantation is a little community, with the master at its head, who concentrates in himself the united interests of capital and labor, of which he is the common representative,” declared Calhoun in 1838. Seven years later, in a public letter addressed to British abolitionist Thomas Clarkson, Hammond wrote, “Our patriarchal scheme of domestic servitude is indeed well calculated to awaken the higher and finer feelings of our nature.”31

South Carolina politicians were not alone in promoting this paternalist ethos. Several influential Charleston clergymen had been saying much the same thing since the 1820s. In the months after the Vesey affair, Richard Furman, pastor of Charleston Baptist Church and a longtime slaveholder, dashed off a proslavery letter, which was then adopted by the South Carolina Baptist convention and published as a pamphlet. Furman posited the master as “the guardian and even father of his slaves,” adding that when treated justly the enslaved became part of a master’s “family (the whole, forming under him a little community) and the care of ordering it, and of providing for its welfare, devolves on him.” Reverend Frederick Dalcho, of St. Michael’s Church, concurred. Guided by their Christian faith, South Carolina’s masters approached their black flock with kindness and humanity, he insisted in an 1823 book.32

As John C. Calhoun brought this paternalist vision to the national stage in the 1830s, he stressed that southern slavery not only “secured the peace and happiness” of master and slave but also proved to be “the most safe and stable basis for free institutions in the world.” The struggle to protect the peculiar institution, Calhoun maintained in 1836, was the South’s “Thermopylae.” John C. Calhoun died fourteen years later, a decade before the South made its final stand in the name of slavery. Fittingly, the South’s most vocal champion of slavery was buried in Charleston. And fittingly, when the South’s Thermopylae came to pass in the form of a full-blown war in 1861, it began in Charleston.33

* * * *

IN THE YEARS leading up to the Civil War, white Charlestonians echoed Calhoun’s benevolent take on slavery. In the process, they transformed the capital of American slavery into the Cradle of the Confederacy. After Harriet Beecher Stowe published her blockbuster antislavery novel, Uncle Tom’s Cabin, in 1852, city residents scrambled to dispute it. Stowe’s book was a frequent topic of conversation—and target of vitriol—among the intelligentsia who gathered at John Russell’s King Street bookshop. The same year Uncle Tom’s Cabin appeared, a Charleston publisher released The Pro-Slavery Argument, as Maintained by the Most Distinguished Writers of the Southern States. Featuring essays by several prominent proslavery voices, including Charleston poet and novelist William Gilmore Simms, the collection sought to counter Stowe’s negative portrait of life in the plantation South. Local lawyer Edward J. Pringle challenged Uncle Tom’s Cabin in a pamphlet he published in 1852, which characterized slavery as a humanitarian institution in which abuses were rare, especially when compared to those suffered by the poor in the industrial North. Four years later, Charleston officials declared that the whole city shared these sentiments. “This community entertains no morbid or fanatical sentiment on the subject of slavery,” maintained a city council committee. “The discussions of the last twenty years have lead [sic] it to clear and decided opinions as to its complete consistency with moral principle, and with the highest order of civilization.”34

The South Carolinian who assumed the mantle of defending that moral and civilizing institution from John C. Calhoun was Robert Barnwell Rhett Sr. In the 1830s, the Beaufort-born politician and newspaperman had been a stronger supporter of nullification than even Calhoun himself. Two decades later, in the wake of Calhoun’s death, Rhett urged South Carolina to secede from the Union after the passage of the Compromise of 1850—a stance that earned him the hearts of the state’s proslavery legislators, who rewarded Rhett with Calhoun’s Senate seat that December. Thereafter, he was South Carolina’s leading proponent of slavery, southern interests, and secession—or a “fire-eater,” as such men came to be called. Rhett beat the drum for immediate secession in Congress until he resigned in 1852 and in the pages of the Charleston Mercury, which he and his son Robert Barnwell Rhett Jr. purchased in 1857.35

Goaded on by fire-eaters like Rhett, Charleston—like much of the South—was approaching a war footing by the late 1850s. After John Brown’s failed attempt to spark a slave insurrection at Harpers Ferry, Virginia, in October 1859, British consul Robert Bunch wrote, “I do not exaggerate in designating the present state of affairs in the Southern country as a reign of terror.” From the consular office on East Bay Street, he reported to London that “persons are torn away from their residences and pursuits, sometimes ‘tarred and feathered,’ ‘ridden upon rails,’ or cruelly whipped; letters are opened at the post offices; discussion upon slavery is entirely prohibited under penalty of expulsion, with or without violence, from the country.” In the wake of Harpers Ferry, white Charlestonians formed a new vigilance society, the Committee of Safety, which pledged to police the community more vigorously than its predecessors had. The committee will not “be deterred by nervous gentlemen or Abolition sympathies from ferreting out these friends and disciples of ‘Old John Brown,’” said one of its members. When the Democratic National Convention met in Charleston the following April, city residents openly intimidated South Carolina’s cautious delegates, strong-arming them into walking out of the convention in response to its moderate party platform. “If they had not retired,” wrote Robert Barnwell Rhett Sr., “they would have been mobbed, I believe.”36

Soon the city tightened its grip on the free black population. In August 1860, Charleston officials started going door to door, forcing blacks—even members of the brown elite—to provide proof of their status or face enslavement. Four months later, free black tailor James Drayton Johnson admitted that, like many in his community, he was contemplating leaving the city. “Our situation is not only unfortunate but deplorable & it is better to make a sacrifice now than wait to be sacrificed,” Johnson told his brother-in-law.37

South Carolina fire-eaters were equally vigilant in declaring that if Abraham Lincoln—the presidential nominee of the antislavery Republican Party—were to be elected in 1860, the state would immediately secede. Charleston merchant Robert N. Gourdin and a number of wealthy Lowcountry planters formed the 1860 Association, which unleashed a storm of propaganda to awaken hesitant whites to the dangers posed by a Lincoln administration. In a matter of months, the 1860 Association printed more than 150,000 pamphlets with menacing titles like The Doom of Slavery in the Union that focused white southerners squarely on the future of the system that kept most black southerners in chains. Worried that the South’s nonslaveholding majority might not be willing to join a revolution in the name of human bondage, these fire-eaters emphasized how the institution served as a bulwark against white servility. “No white man at the South serves another as a body servant, to clean his boots, wait on his table,” Charleston-born editor James D.B. DeBow reminded nonslaveholders. “His blood revolts against this.” A Republican victory put this racial hierarchy, so important to poor and middling whites, at risk.38

Other pamphlets aimed to boil the blood of slaveholders and nonslaveholders alike. Lincoln’s election, wrote Edisto Island planter John Townsend, portended “emancipation . . . then poverty, political equality with their former slaves, insurrection, war of extermination between the two races, and death.” Charleston’s leading fire-eater newspaper joined the chorus too. “Should the dark hour come, we must be the chief sufferers,” warned a self-proclaimed Southern-Rights Lady in the Rhetts’ Charleston Mercury. “Enemies in our midst, abolition fiends inciting them to crimes the most appalling . . . we degraded beneath the level of brutes.” The purity of southern ladies hung in the balance.39

A paramilitary outburst cast a long shadow over the elections that fall. Armed groups drilled in front of convention halls from Charleston to the Upcountry. Unionists were assaulted in the streets. “Not a suspicious person, or event, escapes their notice,” wrote a correspondent to the Mercury of new committees of safety and vigilance created in Barnwell, South Carolina.40

These efforts worked. Secessionists swept the October legislative election. After Lincoln’s victory the following month, the only political choice was between immediate secession and leaving the Union in concert with other southern states. And, when South Carolinians went to the polls in early December to elect delegates to a secession convention, they chose a slate overwhelmingly committed to the immediate course. A unanimous vote was all but ensured as the delegates—90 percent of whom were slaveholders—convened in the state capital of Columbia on December 17. Later that day, the secessionists’ triumph was symbolically sealed when the convention was moved to Charleston because of a smallpox outbreak. On December 20, 1860, the secession convention voted 169–0 to leave the Union. That evening the delegates gathered at Institute Hall on Meeting Street, where they signed the Ordinance of Secession before a crowd of 3,000.41

South Carolina secessionists were quite clear about their motivations. Four days after they voted to break with the Union, convention delegates explained their decision in a “Declaration of Immediate Causes.” Lincoln’s election, they reasoned, represented the culmination of “an increasing hostility on the part of the non-slaveholding States to the Institution of Slavery,” jeopardizing their property, their culture, and their lives. In the words of one delegate, “The true question for us is, how shall we sustain African slavery in South Carolina from a series of annoying attacks, attended by incidental consequences that I shrink from depicting, and finally from utter abolition? That is the problem before us—the naked and true point.” However real abolitionists’ threats, in fact, were, sustaining slavery was certainly the naked point for South Carolina secessionists. Ignoring Lincoln’s protestations that he had no intention—nor, to his mind, constitutional authority—to touch slavery in states in which it was already established, they believed that, as the Charleston Mercury put the matter, “the issue before the country is the extinction of slavery.”42

South Carolinians did not plan to go it alone. “The Southern States,” explained William Gilmore Simms, “are welded together by the one grand cohesive institution of slavery.” But having watched southern states fail to rally to their side in the Nullification Crisis three decades earlier, South Carolina fire-eaters made sure to cover their bases. In early January, the secession convention selected seven commissioners to spread the gospel of secession to other southern states. These secession commissioners stressed time and again that Lincoln’s election foretold the imminent destruction of slavery and the apocalyptic future that would follow.43

When six other Deep South states joined South Carolina to form the Confederate States of America in February 1861, representatives of the new nation made it clear that slavery was the cause that motivated them. Forty-nine of the fifty delegates who met in Montgomery, Alabama, to create the Confederacy were slaveholders. Not surprisingly, they drafted a constitution that explicitly prohibited laws that might undermine “the right of property in negro slaves.” The “cornerstone” of this new government, declared the Confederate vice president Alexander Stephens on March 21, rests “upon the great truth that the negro is not equal to the white man; that slavery, subordination to the superior race, is his natural and moral condition.”44

Weeks later, with thousands of Confederate soldiers camped around Charleston Harbor, the fight to secure southern slavery seemed nearly complete. At the center of the harbor sat Fort Sumter, one of the few federal forts in Confederate territory still in the United States’ hands. Fort Sumter had been under siege since U.S. major Robert Anderson and his small garrison had decamped there the previous December. By April, Anderson’s men were nearly out of food. Rather than surrender the fort, President Abraham Lincoln, who had assumed office in March, sent a ship to resupply it with nonmilitary provisions. This decision prompted Confederate commander P.G.T. Beauregard, acting under orders from the Confederate president Jefferson Davis, to demand the immediate surrender of Fort Sumter or face attack.45

The first shot came at 4:30 a.m. on April 12, 1861. Mist lingered over the water that morning as Confederate troops opened fire from spots across Charleston Harbor. Mary Boykin Chesnut, who was staying in the splendid Mills House on Meeting Street, rushed to the roof to “see the shells bursting.” A few blocks away, along the Battery, Charleston’s wealthiest residents also crowded onto rooftops. Sitting on carpets, chairs, and tables that their slaves had spent the night arranging, they watched the fireworks while they sipped drinks and dined from picnic baskets. A light rain fell throughout the day, but this did not dampen the spirits of the crowds or the intensity of the attack. By April 13, Fort Sumter was on fire. Realizing that he could not hold out much longer, Anderson signaled that he would surrender. Charleston rejoiced. Late into the night, church bells tolled and bonfires burned, marking a victory that had been won without the loss of a single life.46

* * * *

WHITE CHARLESTONIANS ANTICIPATED that the swift and bloodless victory over the Union force guarding Fort Sumter would, like the creation of the Confederacy itself, help guarantee the survival of their most cherished institution. They could not have been more wrong. Instead, it launched four years of war that ultimately spelled the end of slavery. In converting their hometown into the Cradle of the Confederacy—the place where the idea of southern secession was born, where the first vote for secession from the Union was registered, and where the Civil War began—Charleston’s fire-eaters helped speed slavery’s demise.

Some observers detected signs of trouble for white southerners and their slaveholding republic at the very outset of the conflict. Arriving in Charleston two days after Major Robert Anderson’s surrender, Irish reporter William Howard Russell saw militiamen parading through the streets in song. Others crowded into restaurants and taverns to brag about Sumter: “Never was such a victory; never such brave lads; never such a fight.”47

Yet Russell thought the rebels overconfident, especially in light of the enemy in their midst. As Russell passed the Guard House one night, a friend pointed out “the armed sentries pacing up and down before the porch,” their weapons gleaming. “Further on, a squad of mounted horsemen, heavily armed, turned up a by-street, and with jingling spurs and sabres disappeared in the dust and darkness.” This slave patrol scoured the countryside in search of runaways. With the curfew bell ringing in his ears, Russell had little patience for planter claims about “the excellencies of the domestic institution.”48

The underlying problems noted by Russell soon began to take their toll on Charleston’s slaveholders. Although they had launched a war to save slavery, the conflict cracked the foundations of the mental and physical citadels they had spent the last few decades constructing. Since Denmark Vesey’s failed 1822 uprising, the city had “seemed to be in a permanent state of siege,” in the words of one observer. Fears of slave insurrection intensified once the Civil War began. After the Union Army occupied the Sea Islands to the south in late 1861, many planters fled to Charleston with at least some of their slaves, swelling the city’s black population. Rumors of revolt abounded. When slave refugees accidently started a fire that roared through the center of the city in December 1861, destroying more than five hundred homes, elites suspected arson.49

White residents kept up a brave face in public, publishing newspaper articles emphasizing slaves’ fidelity. Privately, however, many Charlestonians said something different. “This war has taught us the perfect impossibility of placing the least confidence in any Negro,” wrote rice planter Louis Manigault in his journal. Mary Boykin Chesnut worried that beneath her slaves’ apparent indifference to the course of the war they harbored insurrectionary thoughts. “Are they stolidly stupid or wiser than we are,” she wondered, “silent and strong, biding their time?”50

By the middle of the war, slaves in Charleston and on nearby plantations began to assert themselves like never before. Some declined to follow their masters to Upcountry plantations; others aided federal soldiers in the area. After Benjamin M. Holmes refused to flee with his owners in 1862, he was sold to a slave trader, who deposited him in a jail in Charleston’s slave-trading district. The literate slave managed to get a copy of Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation, which he read to his fellow prisoners. The president’s liberating words did not stop Holmes from being sold to a man who took him to Chattanooga. When Union forces occupied the Tennessee city, however, Holmes seized his freedom, signing on as valet to a Union commander.51

Countless slaves ran away. Just as he sat down to dinner in his Charleston home on March 3, 1862, John Berkley Grimball received word that roughly eighty of the enslaved men, women, and children living on one of his plantations had fled during the night. The most celebrated escape occurred two months later. In the early morning hours of May 13, Robert Smalls, a slave who served as the wheelman of the Confederate supply boat the Planter, slipped out of Charleston Harbor with the rest of the enslaved crew and nearly a dozen other bondpeople, including his wife and two children. Smalls then turned the Planter over to Union forces, wryly telling one officer that he thought it “might be of some use to Uncle Abe.” The following spring, the former slave, by then a Union pi lot, sailed back toward Charleston as part of a major naval assault.52

Local slave owners responded by meting out extreme punishment. Whippings became more severe, and some masters resorted to shooting disobedient slaves. Meanwhile, city officials passed new ordinances that outlawed slaves from fishing in parts of the harbor vulnerable to the Union fleet and compelled anyone going in or out of Charleston to carry a passport.53

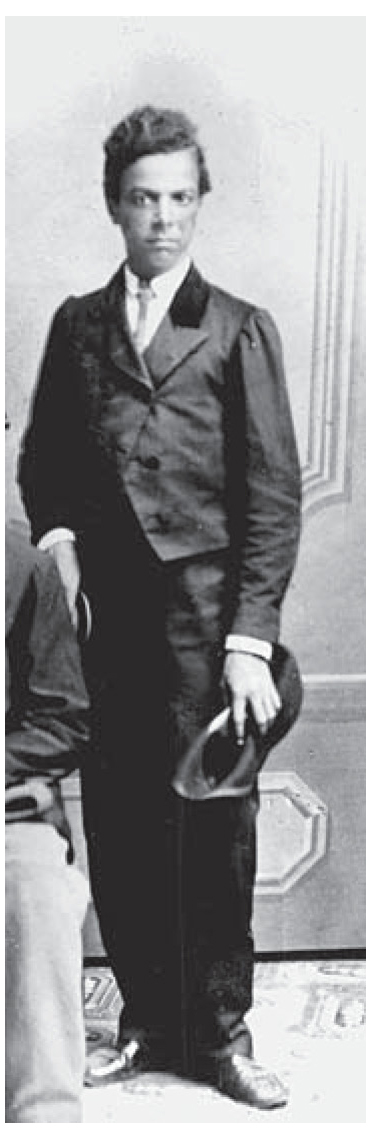

Born a slave in Charleston, Archibald Grimké ran away during the Civil War and later became a prominent lawyer and NAACP leader.

For some slaves, harsher discipline and closer supervision only reinforced a desire to escape. Archibald Grimké, the enslaved son of a planter and a mulatto nurse and the nephew of prominent abolitionist sisters Angelina and Sarah Grimké, was one. As a young boy, Archibald had experienced the partial freedom of Charleston’s free black community, residing with his mother, rather than with his father/master, and enjoying unusual social and educational opportunities. Early in the conflict, he was ordered to move into the home of his new owner and half brother Montague Grimké, who had inherited Archibald, and perform the duties of a family servant. When the thirteen-year-old slave failed to build a fire that suited his half brother’s taste, Montague beat Archibald and then sent him to the infamous Work House, where he was flogged. Soon after, Archibald ran away, disguising himself as a girl to make his way to the home of a free black drayman, where he spent the next two years in hiding.54

As black Charlestonians chipped away at slavery from within, the Union Army and Navy pounded Charleston from without. After failing to take the city in the spring and summer of 1863, Union forces inaugurated what became the longest siege in American history. For more than five hundred days, artillery shells rained down on Charleston, destroying much of the lower peninsula. The Citadel, the College of Charleston, and most hotels and restaurants closed, while other businesses relocated their offices to northern sections of the city. South of Market Street, Charleston looked like a ghost town, as many of its wealthy residents had fled to inland plantations. Union prisoner of war Willard Glazier observed in the fall of 1864 that the lower peninsula—now referred to as the Burnt District—was inhabited only by black Charlestonians, who bolted every time the shelling started, only to return shortly after. The siege was breaking down every rule in slavery’s capital. “Before the siege the poor negroes could only gain admission by the back entrance, where with hat in hand they awaited the orders of ‘Massa,’” wrote Glazier. But now they entered Charleston’s ornate mansions through the front door and took up residence once inside.55

The Union Army would join them in a matter of months. Having burned his way through the heart of Georgia the previous fall, General William Tecumseh Sherman marched his men north into South Carolina in early 1865. Though fearful that Sherman aimed to take the city he called “the Hellhole of Secession,” some white Charlestonians tried to put on a brave face and conduct business as usual. The Charleston Mercury continued to publish advertisements for the private sale and public auction of slaves. The latter took place on the corner of King and Ann streets, beyond the range of Union artillery. On January 19, 1865, in what may have been the final time human beings were offered up to the highest bidder in Charleston, T.A. Whitney sold thirty “PRIME NEGROES,” including several field hands, two house girls, and a one-year-old.56

Several weeks later, P.G.T. Beauregard decided to evacuate the city before Sherman’s army cut off his supply line. By mid-February, Confederate forces and the few remaining wealthy residents had packed up and left, the former setting fire to cotton supplies and munitions on their way out of town. Nearly four years after the Civil War began, the slaves who called Charleston home were at long last free. The capital of American slavery was no more.57