15

Dashes, Hyphens, and Other Punctuation

This chapter covers punctuation marks that, in formal writing at least, are used less frequently than commas, periods, and other punctuation we previously covered. Indeed, some uses of the punctuation discussed in this chapter are occasionally viewed as inappropriate for formal writing, while other functions are fully acceptable.

The punctuation marks covered in this chapter are not as simple as one might think, meaning they can easily result in errors. The hyphen alone has at least 13 functions, although most are straightforward. After a brief summary, this chapter covers the dashes, hyphens, parentheses, brackets, and slashes.

Dashes

The dash technically has two forms: the en dash (–) and the longer em dash (—). The em dash is the one most people consider a “true dash.” Our discussion uses dash to refer only to the em dash, unless noted otherwise. A dash can clarify or emphasize words in three ways.

1. Replacing a colon to set off ideas. This kind of dash sets off words that are “announced” by the rest of the sentence. Almost always, the dash and announcement come at the end of a sentence. What comes before this dash must be able to stand alone as a complete sentence. In this way, a dash can take the place of a colon that sets off an idea which readers would expect to see because of what the sentence says before the dash. Because of the wording in the first part of this sentence, we anticipate the writer to tell us the musician’s name.

I have an autograph of the first female inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame—Aretha Franklin.

2. Phrases that contain commas: Multiple commas close to one another can be confusing, especially if they do not share the same function. A dash can sometimes assist in clarifying things, though not often because it requires a certain sentence structure.

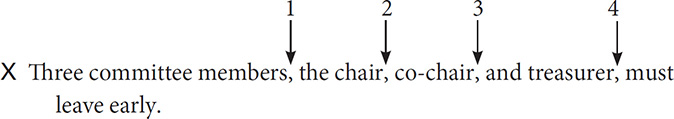

In the confusing example below, the first and fourth commas set off three nouns that form a list. Commas 1 and 4 seem necessary because the list is an appositive for the noun members. However, the list itself contains two commas (2 and 3) that separate three nouns.

Dashes replace commas that would otherwise “surround” a group of words that, for whatever reason, must have their own commas. Another option would be parentheses, which are more formal but less emphatic. In any case, commas can be replaced by dashes only when you could use parentheses, as illustrated below.

Correct: Three committee members—the chair, co-chair, and treasurer—must leave early.

Correct: Three committee members (the chair, co-chair, and treasurer) must leave early.

3. Emphasis: Although often considered overused and informal, the “emphatic dash” can set off ideas a writer wants to stress. Regardless of whether these dashes set off objective information or the writer’s opinion, they can emphasize ideas at almost any point in a sentence.

If you put your finger in your ear and scratch, it will sound like Pac-Man from the old video game—but don’t scratch too hard!

Hyphens

Unlike the em dash, a hyphen (-) merges individual terms (or numbers) into a single idea. Although there are over a dozen specific ways in which it does so, the hyphen should be used sparingly. Here are its more common functions:

1. To join parts of certain compound adjectives and nouns. Examples: five-month-old baby, sister-in-law, and Asian-Americans.

2. To indicate a range of numbers or dates, as in the years 2018-2020.

3. To spell out fractions or numbers from 21 to 99 or fractions, as in one-third and thirty-two.

4. To attach certain prefixes and suffixes, as in mid-June, re-evaluate, and self-sufficient.

Parentheses

The major function of parentheses is to add something that is generally not considered necessary. This so-called “parenthetical comment” usually clarifies meaning or helps make a sentence more readable by breaking some of it into a smaller portion. In all cases, do not put anything inside parentheses that is grammatically essential to the whole sentence.

The three major functions of parentheses are as follow:

1. To provide extra ideas. The wording inside parentheses clarifies previous wording in the sentence or, less often, adds something the writer believes is interesting. Example: “I was contacted by my neighbor (the same person who called you and five other people in the neighborhood”).

2. To avoid awkward sentence structure. In long or complicated sentences, the occasional use of parentheses can help separate some words so that readers can better follow the whole sentence. Example: “Many dieticians suggest that you eat (especially in times of stress and physical fatigue) a higher proportion of high-protein foods, vegetables, and whole grains.”

3. To clarify abbreviations. When you want to use an abbreviation that might be unfamiliar to readers, use the full term first and immediately follow it with the abbreviation within parentheses. Thereafter, use just the abbreviation. Example: Organization of American States (OAS).

Parentheses often involve punctuation that is inside, outside, or both inside and outside the parentheses. There are several scenarios that cause writers problems, but most involve either (1) a comma that goes right outside the final parenthesis or (2) a period that goes outside the final parenthesis. In most cases, this period indeed goes outside the parenthesis but with no punctuation needed before the last parenthesis. And almost never is a comma placed immediately before any parenthesis. The placement of a question mark or exclamation point depends on the meaning of the overall sentence as well as what is within parentheses.

Brackets

Aside from highly technical or specialized writing, all brackets in formal writing set off wording that you add to a quotation. This overall purpose leads to four specific functions:

1. To clarify wording in a quote. Because the quotation is lifted from its original context, some wording might need brief clarification. Example: “We were ordered to disregard his [Mr. Sanders’] testimony.”

2. To point out errors in the quote. Usually this error is grammatical, and you want to let your readers know it was not your mistake. Example: “I had a mindgrain [migraine] all day!”

3. To help show where words were omitted. To be concise, you can use spaced periods (ellipses) to show where you omitted words from a quote. The formal approach is to have spaces between the periods and place them within brackets to make it clear they did not appear in the original. Example: “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, [ . . . ] that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.”

4. To insert changes to fit your style or sentence structure. When you do not so much set off the quotation as work it into your sentence, the wording does not always match up with your syntax or style. In such cases, brackets can add wording within the quotation to make it fit. Example: “As Captain Kirk might say, I want you ‘to boldly go where no [person] has gone before.’” In that sentence, the original word man was replaced by a term that matches the writer’s nonsexist style.

Along these lines, brackets can also be used to indicate where you deleted objectionable words from a quote. Brackets can also be inserted where you used boldface or another special font in order to add emphasis.

Slashes

The slash ( / ) is not common despite many possible uses. The vast majority of slashes share one basic purpose: to indicate a close connection between letters, numbers, words, or lines. This purpose translates into several specific uses. Except with the fourth function, do not place a space before or after the slash.

1. To stand for or. When used this way, it should be possible for the slash to be replaced by or, as in he/she, right/wrong matter. Never use a hyphen as a substitute for the “or slash” even though there are times when other types of slashes can be so replaced.

2. To stand for versus. If the meaning is clear because of your context, a slash can indicate an adversarial relationship. Example: “The Mariners/Yankees game this weekend will decide who advances in the playoffs.”

3. To stand for and. This is the most debatable type of slash, and we suggest avoiding it. It is commonly used to emphasize that something or someone is “both X and Y”—often more emphatically than using these actual words (both, and) or using a hyphen instead. Example: “The specimen has highly atypical male/female characteristics.”

4. To indicate a line break. A slash can indicate where a poem or song originally had a line break—where there was a line that was indented. Use this slash only when you are working the lines into your sentence, not when you show the line breaks by indenting them yourself. Example: “The poet Gwendolyn Brooks wrote, ‘And if sun comes / How shall we greet him?’”

5. To abbreviate numbers and ratios. A slash can be shorthand for certain numerical concepts. For instance, a slash can stand for per, as in “a limit of 35 miles/hour.” A slash can also abbreviate dates, as in 12/21/19. A slash can indicate a time span, as in the 2018/19 season. Or a slash can express fractions such as 1/3.

Dashes

Despite its simple appearance, the dash (—) is surprisingly complex and misunderstood. One misconception is that it has dozens of purposes, whether in a text message or a résumé. Another misconception is that all of these purposes are technically or stylistically wrong.

In terms of formal writing, the truth is that there are widely accepted rules for using a dash, although in only a few types of sentences. While some readers consider the dash overused or informal, it can clarify or emphasize what the writer is attempting to communicate.

What’s the problem?

Dashes entail more than one issue and concern. We focus on four matters: defining, typing, spacing, and usage.

Defining “Dash”

One problem is accurately defining what we mean by a “dash” in formal writing. A dash actually has two forms, but most word processing programs and computer keyboards (digital or physical) make it difficult to produce either type in a single keystroke. Below are the most common definitions of the two types of dashes used in the United States.

em dash: the “long dash,” which most people associate with a dash. Its most common function in formal writing is to set off words from the rest of the sentence (but only in certain situations, as explained below). Example: In 2003, the Academy Award for best original song was given for the first time ever to a rap song—“Lose Yourself.”

en dash: the “short dash” (–), which is longer than a hyphen but shorter than the em dash. Used correctly, the en dash usually means “through” (as in “to”). It thereby can indicate some sort of range (normally involving numbers or, less often, letters). Example: Read pp. 14–31 in your book.

To complicate matters, there is the hyphen (-), which many people mistakenly assume is like the em dash. As explained later, the hyphen is usually reserved for separating parts of a word (as in pre-examination) or for joining two or more words (as in modern-era politics).

In truth, few readers notice or care if a hyphen is used in place of the en dash to separate numbers or letters (as in Rows a-f versus Rows a–f). At one time, the en dash was available only to professional typesetters, but technically it is now available on most word processing programs, complicating matters for everyday writers. Most writers can use a hyphen in place of the en dash, and we recommend doing so unless you are aiming for publication-worthy material, such as a company brochure or website.

Our discussion focuses on the em dash. Unless noted otherwise, we henceforth use the term “dash” to refer specifically to the em dash (—).

Finding the Dash on a Keyboard

Rarely will you find just one key on a keyboard to type a dash, but it is still easy to produce or imitate: Type two hyphens, but with no space before, between, or after them (--). The hyphen (-) is normally found at the top of the keyboard, to the right of the zero (0). Most word processors auto-format (or auto-correct) a double hyphen into a solid dash (—).

If a solid dash does not appear, the double hyphen (--) is acceptable to most readers, unless the writing is meant to appear clearly professional and polished (e.g., a published article). Once again, though, never confuse the single hyphen with a dash.

You can enable or disable the auto-formatting by accessing the appropriate option in your word processing program. Most versions of Microsoft Word require users to go to the “Insert” tab, select “Symbols,” choose “Special Characters,” select “em dash,” and then click on “AutoCorrect” to find the auto-format option you prefer. Another way to produce the em dash is to press the Alt key and type 0151 on the numeric keypad.

Auto-format in Microsoft Word can also produce the en dash: Type the range of letters or numbers you want, placing one hyphen between them. Leave a space before and after the hyphen for auto-format to work. This way, the en dash automatically replaces a hyphen if you type “the years 1940 – 1945” but only if you place a space before and after the hyphen, meaning you must then delete the spaces once the en dash appears (as in “the years 1940–1945”). You can enable or disable this auto-format option in Microsoft Word by again accessing the aforementioned “Insert” and “Symbols” tabs. Or press the Alt key and type 0140 on the numeric keypad.

Spacing and Dashes

Many organizations and publishers have their own preferences about having a space before or after a dash, but following are the most common conventions in the United States:

The “regular” (or em) dash: Do not place a space before or after this dash. And if you must use two hyphens to serve as a dash, do not put a space between the hyphens. Examples: Water—one resource we can never replace. Water--one resource we can never replace.

The “short” (or en) dash: Do not set off with spaces before or after. Examples: Groups A–G. Ages 2–6.

To automatically produce the en dash, some word-processors (such as Microsoft Word) require you to type a space before and after a hyphen. Thus, after the en dash appears because of auto-format, delete these spaces. The en dash will remain. However, most people routinely use and accept a hyphen that takes the place of an en dash.

Using the Dash

For some individuals, a dash (—) is considered “all-purpose” punctuation used when they are in doubt about what to use. Or they just like dashes and assume we all do. With informal writing, most readers are tolerant of overused dashes, but dashes should be sparingly used in formal contexts. Indeed, some readers and organizations prefer no dashes at all, even when they are technically correct.

In this section, we focus on the three major uses of the em dash (see the previous definition), but even these dashes could be replaced with other punctuation or, at times, with nothing at all. As noted previously, em dashes set off words from the rest of the sentence.

Note: All three uses discussed below illustrate how the dash should be reserved for setting off a group of words that is not grammatically essential. The ideas set off by a dash might be very important in terms of meaning, but the sentence would be grammatically complete without it.

Function 1: To Set Off an Introductory or Concluding Idea

A dash can often replace a colon because both can set off words that were “announced” in the other part of the sentence. Typically, this announcement comes after the colon; it is information that readers expect because of what the rest of the sentence says (see the section on colons in Chapter 13). Most often, this dash acts like a colon to set off the concluding part of the sentence, especially lists. What comes after the dash “announces” or “amplifies” a specific idea or word that we expect to see explained. In the following two examples, items and fine are used in a way that makes us expect more detail:

The customer requested several items—pencils, ink cartridges, envelopes, and hummus.

The judge imposed a harsh fine—$25,000.

At times, however, these ideas or lists appear at the start of the sentence, and a dash (or colon) sets of them off from what follows. This “introductory announcement” is used in the following variations of the previous two examples:

Pencils, ink cartridges, envelopes, and hummus—the customer requested all these items.

$25,000—that was the harsh fine the judge imposed.

Function 2: To Set Off Phrases That Contain Commas

In some complicated sentences, a group of words might need two types of commas: (1) commas between the words and (2) commas that set off the whole group from the rest of the sentence. A pair of dashes can replace the second type of comma. Consider how confusing this sentence would be if commas were used instead of the dashes.

Correct: Dr. Lopez—a calm, reasonable, and respected physician—will serve as our consultant.

Remember: Dashes cannot replace any comma. As seen in the above example, dashes correctly replace commas that set off a single group of words that have their own commas. Put another way, dashes replace the “outside” commas for a distinct group of words, while the “inside commas” remain because they are needed to separate words within the group.

Although parentheses de-emphasize the idea being set off, they can replace dashes in this type of structure. Use this type of dash, then, only when you could opt for parentheses, as seen in the following revision of the above example:

Correct: Dr. Lopez (a calm, reasonable, and respected physician) will serve as our consultant.

Function 3: To Emphasize an Idea

Now we come to the dash most likely to be overused or unappreciated in formal writing: the dash whose sole purpose is to emphasize part of a sentence. Unlike the previous two functions, this “emphatic dash” deals not so much with syntax as with a particular concept the writer wants to highlight. That subjectivity is one reason why many readers do not care for dashes in formal writing. These comments are often called “parenthetical remarks” because parentheses can be used instead of dashes to show that an idea is (supposedly) superfluous.

In brief, emphatic dashes set off words and often do not replace any required punctuation. The next two sentences correctly use emphatic dashes, and if they were omitted, no comma (or other punctuation) is firmly required. If commas were used, they too would be for stylistic effect and emphasis, not because of a rule requiring punctuation. Dashes or commas are thus optional in these examples:

Optional punctuation: Report for work by 8:00 a.m.—no matter how far away you live.

Optional punctuation: I am giving you official notice—for the second time—that your punctuality is required.

At times, however, the emphatic dash does replace required punctuation: a comma of some sort. (Why these commas might be required is too varied and complicated to discuss here, so we refer you to Chapter 11 on their many functions.) In these next examples, dashes replace commas that would otherwise be required.

Required punctuation: My only neighbor—Audie Phillips—is moving to Kansas City.

Required punctuation: Audie—who has lived here for 50 years—has mixed feelings about the move.

Finally, some emphatic dashes go further: calling attention to an idea but also suggesting that it is “tossed in” as a personal aside or comment that perhaps is unnecessary. While such dashes suggest that these ideas might be unnecessary, in truth they can convey what the writer really wants readers to notice, as seen in the following second example in particular:

The mayor—and it pains me to say this—resigned last night.

We had heard about her “indiscretions”—and you know what that means—for months.

This variation of the emphatic dash is similar to the “just saying” remark people use informally to say something that is emphatic even though it is allegedly “just” a casual observation. Given such ambiguity, the “just saying” remark should be used sparingly in formal writing.

Hyphens

The hyphen (-) is no less complicated than the visually similar dash. Indeed, dictionaries and usage guidelines do not agree on several aspects of hyphenation, such as when to use the slightly longer en dash (–) or when to use nothing at all in a particular compound word.

As stated previously, the em dash (—) should never be mistaken for a hyphen. Thus, to understand what a hyphen does and does not do, read the previous discussion on the dash, especially the em dash. Both the hyphen and the slash ( / ) can join words, so also read the section later in this chapter on slashes.

Unlike the em dash, the en dash can almost always be replaced by a hyphen in formal writing. The en dash (–) is shorter than an em dash (—) but longer than a hyphen (-). Some punctuation guidelines still require the en dash in certain situations (e.g., a range of page numbers or even with certain types of compound words). Still, relatively few readers or organizations expect people to use the en dash even in unpublished formal writing, as this dash is normally the concern of professional typesetters and editors.

We therefore suggest using a hyphen even in situations when a publisher or typesetting specialist might replace some hyphens with en dashes.

When to Use a Hyphen

A thorough list of when to use a hyphen is daunting, but keep in mind this overarching function:

Hyphen = combining two or more language choices into one idea

Whether the hyphen combines two words (well-being), adds a prefix to an adjective (half-empty glass), or it can, like an en dash, indicate a range of numbers (pages 2-12)—the hyphen creates a single idea out of two or more concepts. But keep the hyphen in reserve for when it is truly needed, such as clarifying the intended meaning of a word. For instance, one might use re-sign (as in signing a document again) rather than resign (to quit).

For those needing more detail, below is a summary (in no particular order) of the most common situations permitting or requiring a hyphen. Categories marked with an asterisk (*) are explained more fully afterwards.

1.* To join complete words in certain compound adjectives. More specifically—to join two or more complete words that together serve as a single adjective which describes a noun that comes afterwards: well-dressed person, a one-way street, ten-year-old child, state-of-the-art computer, two-person bed, a grown-up’s approval, half-empty glass, check-in time, five-dollar fee.

2.* To join complete words to create certain compound nouns: my mother-in-law, your well-being, several four-year-olds, a pick-me-up, a stop-off, a recent break-in, editor-in-chief.

3.* To indicate a relationship between people or things in a compound noun or adjective: the suburban-urban population, a mother-daughter connection, a McGraw-Hill publication, Chicago-Detroit flight, U.S.-British policy, African-Americans, Jane Doe-Smith, Soviet-European tensions.

4. To spell out compound numbers from 21 to 99: forty-two, fifty-fifth, sixty-eight, one hundred and thirty-two.

5. To spell out fractions or proportions: one-fourth of the winnings, two and one-half miles, two-eighths of a meter, a half-hour discussion.

6. To separate numbers that are in numeral form: from 2001-2005, a score of 14-3, vote of 42-12, pages 13-21, 2-3 odds, ratio of 2-1. (A colon can also indicate odds or ratios, as in 2:3 odds or a ratio of 2:1).

7. To join a letter to a word. B-team, X-ray, X-Men, T-shirt. (Some dictionaries provide a nonhyphenated option for a few words, such as X ray.)

8. To join a prefix with a number, an abbreviation, or a proper noun: pre-1900, mid-80s, pre-NATO, mid-April, non-American, Trans-Pacific, neo-Aristotelian.

9. To join a prefix to a word that starts with the same vowel that ended the prefix. Examples: anti-immune, anti-intellectual, re-enter, retro-orbital, semi-informal, semi-identical, co-op, pre-emptive.

Note: Despite many exceptions, a hyphen is sometimes used when different vowels are involved (as in semi-arid, anti-aging, meta-ethnic). While some style guides say that it all depends on certain combinations of vowels and that the hyphen helps with pronunciation, these details are difficult to remember. A reliable dictionary is the best tool.

10. To attach certain other prefixes: all-knowing, self-aware, self-service, ex-president, half-baked, quarter-pounder, semi-illiterate.

Note: The prefixes all-, self-, and ex- usually require a hyphen, but hyphenation with other prefixes is again difficult to predict, largely because it is a matter of whether the word “looks awkward” or could be mispronounced. Again a credible dictionary will usually resolve the matter.

11. To attach the suffixes -type, -elect, and -designate: administrative-type decision, the president-elect, the governor-designate.

12. To divide a word at the end of a line if the entire word does not fit. The hyphen is placed between syllables: super-visory, docu-ment, semi-relevant.

13. To indicate that you are creating a word having distinct parts: a Kennedy-esque incident, semicolon-ize the sentence, three not-cat pets. This “invention” is usually done in a payful (and one-time) way.

More on Hyphens With Compound Adjectives

In Category 1 above (compound adjectives), each sample adjective precedes a noun. The hyphen makes it clear that certain words work together as a single concept describing a noun. The first sentence below uses one of the examples, while the second sentence incorrectly omits the hyphen.

Correct: Your check-in time is 3:30 p.m.

X Your check in time is 3:30 p.m.

Readers of the first version probably would not think it refers to “your check” or to “in time.” The second sentence, however, looks awkward, especially compared to the hyphenated version.

Still, compound adjectives are not always hyphenated, especially when there is little or no chance of misreading them or awkwardness. Hyphenation often depends on where the adjective appears in relation to the word it modifies. Remember the following rule of thumb:

A typical example of this tip occurs when a compound adjective appears after a linking verb (such as is, are, was, were). The adjective “bends back” to describe the subject of that verb. In the following three correct linking-verb sentences, no hyphen is needed for the underlined compound adjectives:

That street is one way.

Mr. Dibny was well dressed as usual.

The glass appears half empty.

Even though they are listed above in Category 1, the single-underlined adjectives above all come after the double-underlined nouns they modify. As a result, the adjectives are neither confusing nor awkward, suggesting that they should not be hyphenated.

More on Hyphens With Compound Nouns

As with compound adjectives, avoid hyphenating every concept that is composed of separate words. Admittedly, whether or not a compound noun is hyphenated might seem arbitrary, yet there are reliable guidelines and resources.

Compound nouns are likely to appear in credible dictionaries, and spellcheckers are also useful in determining if a noun needs a hyphen. Some dictionaries indicate that the hyphen is optional in some words. Again, the preference nowadays in professional or formal writing is the nonhyphenated option. In fact, some compound nouns that once were frequently hyphenated no longer have a hyphenated option in many (but not all) current dictionaries and style guides, email and chatroom being relatively recent examples.

Don’t confuse compound nouns with compound adjectives. Some terms, with slight modification, can be either. It depends on how they are used in a sentence.

Hyphenated compound adjective: Several four-year-old children ran amok in the theater.

Nonhyphenated compound adjective: The children running amok were four years old.

Compound noun: Several four-year-olds ran amok.

Compound noun: I saw several four-year-olds run amok.

The first sentence above correctly hyphenates the compound adjective because it appears before its noun. The second sentence correctly omits the hyphen in accordance with the tip given above. That is, four years old appears after the noun it describes. And the last two sentences contain compound nouns that all grammar style guides would hyphenate, no matter where the words appear in a sentence. The aforementioned grammar tip for compound adjectives is thus irrelevant for compound nouns.

More on Hyphens Indicating a Relationship

Although hyphens join words and ideas that are closely related, Category 3 in our list refers to how some hyphenated words reflect even more of a “joint venture” or partnership—emphasizing the nature of that relationship as a whole, not the meaning of each individual word. In mother-daughter connection, for example, the term mother is not describing daughter. Instead, the two words work equally together to refer to how two family members relate to each other. Using a hyphen rather than a slash is considered more acceptable (see our section on slashes above and later in this chapter).

In regard to the example Jane Doe-Smith, we can assume that Jane used a hyphen to establish a name that reflects an identity associated with two families. As with many compound proper nouns, this hyphen is optional and is up to the discretion of the individual whose name it is.

Similarly, the hyphen has long been used to join words to create proper nouns and adjectives that indicate ethnicity or cultural identification (Afro-American, Asian-American, Irish-Americans, Anglo-American, etc.). Although there are strong opinions on this matter, the current trend across a diverse range of communities and contexts is to omit the hyphen.

Parentheses

Parentheses come in pairs (as shown here), but the term parenthesis refers to just one mark. The most widespread use of parentheses is to set off words, phrases, a sentence, or even many sentences that are not strictly necessary—either grammatically or in terms of meaning.

First, we offer a more complete list of when parentheses can be used. Then, we provide a guide for using other punctuation placed near parentheses.

Function 1: To Provide “Extra Ideas”

This function results in what people call a “parenthetical comment”: an idea that might not be essential but that adds clarity or, less often, something the writer believes is interesting—such as an aside, a digression, or humor. While commas or a dash can achieve the same purpose, parentheses may be sparingly used in most writing to set off extra ideas.

Beware of putting truly essential information in parentheses, but sometimes a sentence is not completely clear without a parenthetical clarification. That apparent contradiction means that the rules can be flexible in this regard. In the first example below, parentheses set off a definition that most people would need, but parentheses are still correct because the sentence technically provides all the needed information.

Fortunately for him, Tarzan did not suffer from dendrophobia (a severe fear of trees).

In the next example, the parenthetical comment might clarify the matter but is supposedly not truly essential. A reader might still wonder if this particular information is a “hint” about a point the writer wants to make without explicitly stating it. In any case, the parentheses are technically correct even if misleading about the writer’s real point.

Four employees (two newly hired, two long-time employees) forgot their badges this week.

The next two examples fall more into the “aside” category: an interesting fact or comment. The first sentence below seems more like a trivia item when compared to both of the previous examples. The final parenthetical comment provides a personal opinion, not just information:

Mel Gibson was the first actor to portray Mad Max (whose real name according to the first film was Max Rockatansky).

Max was played by one other actor (the one who also played a great villain in a Batman film).

It is often difficult to distinguish between a parenthetical comment intended as useful information versus an aside with less-functional commentary, innuendo, or minutia. The context might clarify the intent, but clear communication avoids parenthetical comments that invite people to read between the lines (or between parentheses) to discern the author’s meaning.

Function 2: To Avoid Awkward Syntax

While they should not be overused, parentheses can set off related words to make a sentence more readable. This function is similar to the previous category of parenthetical elements, but parentheses do not always depend on simply whether the language adds content or is interesting. By setting off a group of words, parentheses can also make complicated sentences easier to read.

Commas (or dashes) can achieve the same purpose, but often parentheses make a sentence less confusing by cutting down on the number of commas already within it. Note the complexity of the following examples and how setting off certain parts makes each sentence easier to follow:

The most famous features of peacocks (the crested head, brilliant plumage, and extremely long feathers) are found only among the males.

Despite numerous exceptions, a hyphen is sometimes used after a prefix that ends with a vowel different from the other than the vowel that starts off the root word (as in semi-arid, anti-aging, meta-ethnic). Dictionaries and style guides are not in agreement about many of these words, so use the form that is consistent with the resource you or your organization normally follows.

Function 3: To Clarify an Abbreviation

This category is also a type of parenthetical comment but deserves its own discussion due to the importance of this overlooked (or sometimes overused) function. In brief, parentheses can explain an abbreviation that might be unclear to readers.

The most common approach is to use the full form of the word or words in the abbreviation first and immediately follow it with an abbreviated form that is placed in parentheses. Thereafter, use only the abbreviation, assuming your readers have seen and remembered what it means.

The British Broadcasting Company (BBC) made a surprising announcement early this morning. Six hours later, the BBC retracted the announcement.

Another approach is to start with the abbreviation and follow it with a parenthetical clarification. This option works satisfactorily when most, but not all, of your readers already know what the abbreviation means.

Paul said that he will BRB (be right back). He’d better BRB if he wants to ever text me again.

Function 4: Specialized Uses

Parentheses have a few other purposes, mostly relating to certain types of writing or situations. Below are three specialized uses:

1. In writing that incorporates formal research, most documentation systems call for parenthetical citations to indicate the writer’s sources. Two of the most common systems requiring parentheses are the MLA (Modern Language Association) and the APA (American Psychological Association). In all these systems, any ending period goes outside the parentheses. Example: The governor spent $450,000 on advertisements in the last month of the election (Greene, 2018).

2. To enhance readability or be emphatic, you can also place numbers or letters inside parentheses to separate related items, such as in a list. Keep the same grammatical structure after each parenthesis. Example: You need to provide (1) evidence that your trip dealt with company business, (2) receipts for all expenses for which you seek reimbursement, and (3) a written explanation covering why you took a three-day detour to Miami.

3. Parentheses are also often used in technical writing, especially when dealing with mathematics, formal logic, chemistry, or computer sciences. Example: If (a AND b) OR (c AND d) then . . . .

Parentheses and Other Punctuation

No matter which function is involved, parentheses sometimes appear right next to other punctuation, most notably at the end of a sentence. The following guidelines apply to practically any function of parentheses:

• For sentences ending with parentheses, the most common pattern by far involves a normal (declarative) sentence. It requires a period outside the closing parenthesis, usually with no end punctuation that appears immediately inside the closing parenthesis. Accordingly, none of the following three correct examples should have a period inside the parentheses.

One major change with this product concerns its UPC (Universal Product Code).

Rubber bands last longer when stored in a refrigerator (they can also be easier to find).

A landmark study supports this claim (Fries and Snart, 2001).

As seen below, a final period is required even if whatever is inside parentheses is a question or and exclamation. But in those rare situations, place a question mark (?) or an exclamation point (!) immediately inside the final parenthesis.

The only U.S. state having a name with just one syllable is Maine (is this an important fact really?).

The officer gave me a speeding ticket (I was only 10 miles over the limit!).

• If the entire sentence is a question or an exclamation, place a question mark or an exclamation point outside the final parenthesis, regardless of what is inside the parentheses. Again, there is no need for a period before the final parenthesis.

Can you attend the interrogation of Mr. Nygma this Friday (7:30 a.m. in room 111)?

On rare occasions, however, end punctuation is used twice. As seen in these two examples, place the question mark or the exclamation point inside the final parenthesis if that material by itself is a question or is exclaimed.

Did you know that the movie Blade Runner is based on a novel by Philip K. Dick (Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?)?

The officer gave me a speeding ticket (I was only 10 miles over the limit!).

Because the first sentence as a whole is a question, a second question mark is needed outside the parenthesis. The second sentence needs a period outside the final parenthesis, even though there is a nearby exclamation point for the parenthetical statement.

• If the entire parenthetical comment is a complete sentence, putting the comment entirely outside the previous sentence is optional. In such cases, place appropriate punctuation inside the final parenthesis, not after it.

Fredric Baur invented the method for packaging Pringles. (When he died, his ashes were buried in a Pringles can.)

Steve left work early today. (Or was it yesterday?)

• Do not put a comma immediately preceding any initial parenthesis. A comma might be needed after the second parenthesis, but it has nothing to do with using parenthesis.

When completing the required document (the Project Management Report), be sure to initial each page.

Shel Silverstein is known for his children’s books (such as The Giving Tree), but he also wrote the song “A Boy Named Sue,” made famous by country singer Johnny Cash.

Brackets

In the United States, the word bracket by itself refers to a specific punctuation mark that always comes in pairs: [ ]. Outside the United States, these are sometimes referred to as square brackets. Except for specialized uses in technical fields (e.g., phonetics, mathematics, and computer programming), almost all brackets are limited to one basic purpose:

Brackets = setting off material that is inside a quotation—but not part of the actual quote

This general purpose leads to several more specific functions.

Function 1: Clarifying Quoted Material

First and foremost, brackets are used inside direct quotations in order to clarify wording that might otherwise be confusing, mainly because the quotation appears out of context. Clarifying a quoted pronoun is especially common, although other terms might also need a bracketed explanation.

In her e-mail to the chief engineer, Dr. Landers stated, “She [the assistant engineer] must request approval for additional supplies.”

The plaintiff said, “My new employer [Dunder Mifflin, Inc.] offered a higher salary and better working conditions.”

Brackets can also clarify by translating foreign terminology, but only within a direct quotation (in other situations, use parentheses).

Our Swahili friend wrote, “Although I hope we meet again, kwaheri [good-bye] for now.”

I replied with the traditional Klingon farewell, “Qapla’ [Success]!”

Function 2: Identifying Errors

Brackets can indicate that you as the writer realize that a direct quotation contains an error, usually a grammatical or spelling mistake. Appearing immediately after the error, the bracketed material either corrects the error or uses the term sic (usually italicized) to point out that the mistake is not the writer’s doing.

You wrote in your report that, “you had enuf [enough] of your supervisor’s attitude.”

You wrote in your report that “you had enuf [sic] of your supervisor’s attitude.”

While not the traditional approach, it is largely acceptable to use just the bracketed correction, omitting the original error.

You wrote in your report that “you had [enough] of your supervisor’s attitude.”

Function 3: Indication of an Omission

Brackets used with ellipses (spaced periods) indicate the place where you left out part of a direct quotation for the purpose of being more concise. Some style guides indicate that brackets are not needed with ellipses, but brackets clearly indicate that you added ellipses and that they were not in the original:

In Lord of the Rings, J. R. R Tolkien wrote, “It was as if they stood at the window of some elven-tower, curtained with threaded jewels [ . . . ] kindled with an unconsuming fire.”

Function 4: Making Other Stylistic Changes

Brackets can indicate that you changed someone’s language to make part of the quote fit into your own syntax or style. The first sentence below uses lowercase (rather than the original capital letter) in those to make it fit the way the sentence integrates the quote. The second example replaces Johnson’s original he with us so that all pronouns in the sentence are plural (and not gender specific). Take great care not to use new wording that distorts the original meaning:

I agree with John F. Kennedy that “[t]hose who dare to fail miserably can achieve greatly.”

As Samuel Johnson would remind us, our true measure as a people rests in how we “treat someone who can do [us] no good.”

In addition, brackets can indicate that original words were deleted entirely because they were offensive or incomprehensible.

According to the audio recording, the salesperson said, “Take your [expletive deleted] credit card and shop elsewhere!”

The customer walked away and said: “Fine, but I will talk to your supervisor before I go to [inaudible wording].”

Finally, if you use a special font (e.g., underlining, italics, boldface) to emphasize words, the conventional approach is to place [emphasis added] within the quotation.

As Martin Luther King wrote, “Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere [emphasis added].”

Slashes

Despite a surprising number of functions, the slash ( / ) is rarely used in formal writing, although it appears relatively often in programming languages, web addresses, chemistry notations, and even some social media messages. Technically, this punctuation mark is a forward slash, as opposed to the backslash ( \ ) that has no conventional use in formal writing. The term virgule and solidus refer to a forward slash, and at one time it was frequently called an oblique.

We use slash to refer specifically to a forward slash ( / ).

Almost all slashes in formal writing come down to one overarching purpose:

A slash indicates a close connection between letters, numbers, words, or lines

Regardless of its specific use, a slash rarely has a space right before or after it. The exception deals with lines from a poem or song, as discussed below.

What’s the problem? The problem with the slash involves the first three of the five functions we describe below. Put briefly, readers might not know whether a slash is used to combine a pair of words stands for or, versus, or and.

Indeed, the most common function of a slash in nontechnical writing is to connect two words, but only in specific cases. Some instances allow either a hyphen or a slash, but not always. As seen in the following two sentences, hyphens and slashes can have different meanings:

Use your student-teacher discount. (A discount for someone who is both a student and a teacher.)

Use your student/teacher discount. (A discount for someone who is either a student or a teacher.)

Although context can clarify such matters, it is best to avoid a slash for combining words unless you are sure that it is used clearly and correctly. Even when the slash is technically correct, consider the alternatives, such as replacing the slash in the last example above with the coordinating conjunction or (as in student or teacher discount). When using a slash effectively, it will usually achieve one of the following purposes.

Function 1: To Mean Or

As noted, a slash can mean or—as in one or the other of something, but not both. This type of slash, even though it can almost always be replaced by or, is one of the most common uses:

Each person should complete his/her own report.

Your grading for this course will be pass/fail.

Every man/woman who served in the military will receive a discount.

We can begin the meeting only if/when the CEO arrives.

You can use this voucher for lunch and/or dinner.

The last sentence above might appear to refer to both words (and, or). However, and/or is still making a distinction between two options: using the voucher for both meals or using it for just one.

Function 2: To Mean Versus

Some slashes take the “or” distinction between ideas further by indicating a conflict or competition. This function is effective only when the sentence and context make this meaning clear. In the following examples, the noun after each italicised term helps readers interpret the slash as versus. This slash cannot be replaced by or, and a hyphen would incorrectly indicate a collaborative, rather than competing, relationship between two ideas.

The liberal/conservative division in this state has intensified.

I am interested in the Cowboys/Eagles game this weekend.

The creationism/evolution debate is far from settled in many areas of the country.

A rural/urban rivalry arose once the government cut agricultural funding.

Function 3: To Mean And

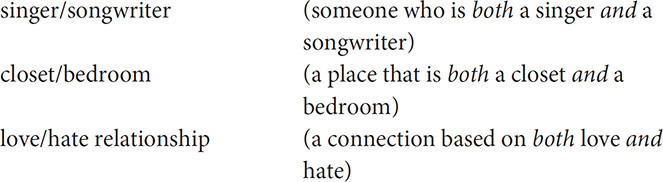

For better and for worse, a slash is often used to replace the coordinating conjunction and. More specifically, think of this slash as emphasizing how something is “both X and Y”:

Important: This use of a slash is the most precarious of all its functions. Some style guides discourage or prohibit a slash meaning and because people overuse it, especially when a hyphen is needed or preferred (see our previous discussion on hyphens with compound nouns and adjectives.)

Even so, an occasional slash can sometimes effectively mean “both X and Y,” much like certain hyphens. Compared to a hyphen, a slash creates a firmer boundary between X and Y so that the reader understands that X is not modifying Y. We suggest using this slash only when a hyphen might not convey the intended meaning, especially for readers unfamiliar with a given term or idea.

My cousin is interested in the MA/MFA program at a nearby university. (To readers unfamiliar with graduate programs, MA-MFA can suggest a progression from an MA to MFA—or perhaps a type of MFA.)

Paulo is our secretary/treasurer. (Readers unfamiliar with organizational titles might assume that the hyphenated form is a type of treasurer, rather than one person being both secretary and treasurer.)

We will study the legacy of the Reagan/Bush approach to economics (For many readers, Reagan-Bush can suggest a progression from one president to another, but the slash can refer to an approach formulated by both men and not necessarily just during their presidencies.)

In sum, use a slash to stand for and only when the hyphenated form might be confusing.

Function 4: To Indicate a Line Break

In contrast to the above three functions, some slashes do not involve meaning. They just show where a line break originally occurred in something you are quoting—such as lines from a poem, song lyrics, or any instance when the original line break is important. Normally, one sets off such lines by indenting all of them and providing line breaks exactly as they appear in the original work. The slash is used only when you directly quote two or more lines within your own sentence.

In a poem about the Cuban Missile Crisis, Margarita Engle describes what she did in school during “duck and cover” drills: “Hide under a desk. / Pretend that furniture is enough to protect us against perilous flames. / Radiation. Contamination. Toxic breath.”

The rock song “Sweet Child o’ Mine” by Guns N’ Roses begins with a loving tribute to one band member’s girlfriend: “She’s got a smile it seems to me / Reminds me of childhood memories / Where everything / Was as fresh as the bright blue sky.”

Because this type of slash combines more than just two words, it is the only slash that can have a space before and after.

Function 5: To Abbreviate and Condense Numbers, Dates, and Ratios

Although usually considered informal at times, a slash can serve as shorthand for concepts involving numbers or ratios. Below are instances of the “abbreviating slash” (outside the United States, these conventions might differ, often calling for a hyphen instead):

To stand for per in a ratio: $15/hour wage, a speed of 65 miles/hour, gas mileage of 40 miles/gallon.

To abbreviate dates: 7/1/57, 8/12/2018, the events of 9/11. Spell out most dates in formal writing (9/11 is an exception), but slashes or hyphens are frequently used to provide dates on forms and applications.

To indicate a time span: the 2018/19 fiscal year, 1992/3 basketball season (this format is acceptable but not as common). The slash is limited to indicating two consecutive years, and the second year must be abbreviated to one or two numbers. A hyphen is often used to indicate a time span and is more flexible, because it can cover more than two years and the last year does not have to be abbreviated (2018-2019 is thus correct).

To express fractions in numeral form: ½ or ¼ (use hyphens if written out, as in one-half or one-fourth).

Summary

• Dashes come in two forms: the em dash (—) and the en dash (–) which is shorter than the em dash but longer than a hyphen (-). The en dash is normally only the concern of publication specialists and can normally be replaced by a hyphen.

• The em dash (—) is often considered informal but has several legitimate functions. All functions involve a dash being used to set off words from the rest of the sentence, but only in certain situations and sentence structures.

• A hyphen (-) combines two or more language choices into one idea. A hyphen should be used only in certain circumstances, such as spelling out fractions (one-fifth) or indicating a range (2012-2019).

• The most common use of parentheses is setting off “extra ideas” from the rest of a sentence. The words inside parentheses should not be grammatically essential to the rest of the sentence.

• Brackets are primarily used to set off clarifying material that is placed inside a direct quotation but is not part of the original quote.

• A slash ( / ) is used in special circumstances to indicate certain connections between letters, numbers, or words. One of the more common functions is to stand for “or” (he/she).