Afterword

It’s July 4th 2006. Independence Day passes pretty much unannounced in territories outside of North America. The weather in the UK is as blistering as it was 30 years ago and over coming weeks temperatures will top anything 1976 had to offer. The hosepipe ban is in force again this year, but now everyone knows why it’s so darn hot!

Political discontent today relates more to foreign policy than anything out-of-the-ordinary on the home-front; and while there’s still a million people out of work in Britain, the goalposts have moved exponentially over intervening decades and such a level is now considered rather low - bearing in mind during the early 1980s it ran at 3 times this figure. There are two main issues on the agenda right now that cause major concern to much of the population. One is the state of the earth and whether we can reverse the effects of everything we’ve been doing wrong since the industrial revolution. But with the majority of those who are employed in the affluent world almost addictively spending money they haven’t got on things they don’t need, the future for subsequent generations looks bleak. The other is the ongoing threat of terrorism, which now seems a thousand times worse than that faced by British mainlanders in the mid-70s, when the Troubles in Ireland had only recently spread to Great Britain.

On this day in 1976, as stated at the beginning of this book, punk was only just kicking off in England, but since the beginning of 2006 every monthly rock music magazine, and the one remaining weekly, have been putting out ‘Punk Specials’, in commemoration of that oeuvre’s Diamond Jubilee, as if their circulations depended on it: by April, unsold copies had been sent back to the publishers. The rather accurate types who edit these periodicals, for once seemed unconcerned with exactitude, instead employing a first-past-the-post regime to signal their credentials in this arena.

While this approach is somewhat understandable and can be seen either as sharp commercial practise or cynical marketing, depending on which side you dress (either way a window still exists for further excursions later in the year), it says more about punk itself than the compilers of these ‘collector’s items’. What was often considered a necessary but short lived novelty at best, an ugly undignified era of rudeness and loud shouty records at worst – but in any case one that was over in the time of a seasonal sale, a stock clearance and a special offer – has tended to resonate loudly ever since; but never as loudly as it does today.

The nostalgia trend of course greatly contributes to this deluge of ephemera, but last year saw the 50th anniversary of rock’n’roll itself – surely a more significant event in the diary of modern music – but nary a mention in any one of these journals was witnessed – with the exception of Elvis Presley’s achievements, acclaimed for far more than his first few records. Likewise, the hippy movement and associated trends have had any number of potential celebrations open to them over recent years, and while there still is plenty of coverage for this era in its various guises, it doesn’t come close to the plethora of punk outpourings.

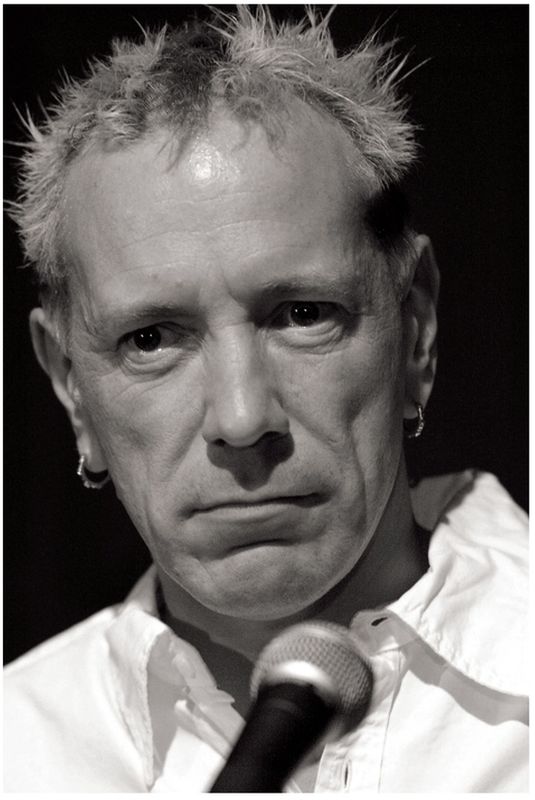

‘One of the first things I was ever quoted as saying was “I’ d like to see more bands like us”. Right? When I said that, I didn’t mean exactly like us. Unfortunately that’s what happened. Imitations. Billions of them. And I wanted nothing to do with any of them. There were a few originals, but not many.’ John Lydon 1977

John Lydon came to hate punk as soon as the multitudes cottoned on. When it existed as an underground movement of true originality and, to a certain degree, an extension of his own persona, his contributions were delivered proudly. Once it became the inevitable rule book of dos and don’ts and it presumed a limited outlook, it was as good as finished as far as he, and, to be fair, others from punk’s sharper edge, were concerned.

As Lydon was pivotal to the necessary emergence of punk, he was equally important to its downfall – or more accurately, its evolution. A feebler soul would perhaps have considered the commercial potential of stringing it out a couple more years and shut up about trivial grievances, but Johnny wasn’t of that ilk. Of the various factors that contributed to the Sex Pistols’ split in early 1978 – which prompted so many others involved to move on, give up or mutate – none was so important as Lydon’s feeling that quite what it was he had contributed to punk so eloquently, was no longer appreciated. One of John Lydon’s musical inspirations, Neil Young – no fool himself – used Lydon as the subject for his all too good advice, ‘It’s better to burn out than to fade away’ a year later. But Lydon knew that already.

So when he found himself without a band, less than three years after he’d first been elbowed into one, as a non musician, a rather acquired vocalist, and a songwriter who couldn’t work alone, he may have found it difficult to envisage many options.

After the Pistols, John was legally forced to revert to the name on his birth certificate – or at least something not ending in Rotten – due to the immediate freezing of any assets associated with Malcolm McLaren and his limited company, Glitterbest – which, it appears, included John Lydon’s nom d’everything for the past 30 or so months. But that suited him fine; enough is enough after all and the return of the artist formerly (un) known as John Lydon, in the latter half of 1978, was, if anything, embellished by the use of his non-punk associated family name.

The years that followed, in Lydon’s new and just as radical collective PiL, are covered expertly and in-depth at the core of this book, but what is interesting about his pioneering role in what has come to be termed post-punk, is that, both in historical terms and in punk-rock itself, there was nothing to suggest it was going to happen. In the wake of rock’n’roll’s first wave, which itself ‘burnt out’ in as short a timespan as punk, came a barrowload of nancy boys with a watered down, limp and soggy rendering of the form. The wild beasts that comprised the cream of rock’s awakening were not replicated. With a few notable exceptions, it would take the best part of a decade for a new galaxy of brighter stars, infused with the rock ethic, to come up with something of their own.

But with punk being just as startling and life-changing as rock’n’roll, 20 years before, it had the same sense of an all encompassing movement; an era of its own with little to recommend it beyond its presumed natural cycle. That it merged into any number of valid follow-on movements – New Wave, Ska (and to a lesser extent, Mod) revivals, Power-Pop, New Romanticism, Liverpool’s new-Psychedelia and perhaps its most logical descendant, Post-Punk – until recently virtually undocumented but now more fashionable a form to namedrop than anything else from the rock era – is quite astonishing. Each of these media-tagged styles had their share of the good, the bad and the much in-between, but such a generally positive fallout – should anyone during those amphetamine fuelled months have had the capacity to sit down and think about it – was wholly unexpected.

Suggestions that post-punk was actually a far more realised, ambitious and creative form than its forerunner have made for a popular view, which when expressed is often tied to intellectual reasoning and wordy explanation: but such rhetoric misses the target on two counts. While John Lydon and a few others, such as Howard Devoto – out of Buzzcocks and into Magazine when the Sex Pistols were still a viable commodity – and Subway Sect’s Vic Goddard – essentially an anti-Rock explorer whose rouse came via punk but who ultimately went in more directions than Spaghetti Junction – had actually planned moves out of the gig they were questioning the validity of and into whatever next took their fancy, for the most part what has come to be labelled post-punk was created by punks, albeit ones who’d either naturally moved on as bands and performers, or were too young for the first wave. The sonic sophistication that put the Banshees debut ahead of The Damned’s, was 15 months of record company wrangling. Equally, the essence of the argument that puts the new form in front of its father-figure is based on a twisted logic that somehow suggests post-punk could have existed alone. With all due respect, ‘Rip It Up And Start Again’ – the title of a recent study of punk’s mushroom cloud – isn’t quite what happened.1

Post-punk is such a ‘one size fits all’ description for so much that came along after the main event, but which didn’t slot into any of the other categories mentioned above, it can’t be claimed exclusively by any individual or band – and certainly no flamboyant mover or shaker , however visionary, had any involvement in its strictly organic unfolding. But the bit of it that John Lydon and his new partners, Keith Levene and Jah Wobble, pioneered, was certainly a form original to PiL, albeit with nods, nay bows, in the directions of dub-reggae, prog-rock2 and, god forbid, punk. Further, suggestions that Lydon wasn’t a creative equal in his new assembly are as unfounded as those on the blunt edge of the punk vs. post-punk debate.

But few would argue that most of the music made by John Lydon once the original PiL line up was no more was inferior to what came before. Opinions differ, but even the oft-acclaimed third studio album, Flowers Of Romance, produced without the fitting bass lines of Jah Wobble, made PiL sound less compelling, rhythmic, and ultimately listenable. Once Levene split too, Lydon was without a collaborator with whom he could ping-pong ideas, for the first time in his career.

So while there were moments of glory still to come, most notably collaborations with like-minded Time Zone, Bill Laswell – under his Golden Palominos brand – and most notably, Leftfield – with whom John Lydon created one of dance music’s most enduring performances on ‘Open Up’ – and also on occasional delights still under the PiL banner, such as ‘Rise’, among 1986’s best singles, these were few and far between, and were largely overshadowed by what many saw as foolishly impulsive decisions. But if treading the boards with a hotel cabaret act and performing a set that included a cheesy ‘Anarchy In The UK’ as a finale every night, and with whom he’d, later on the same tour, attempt further forays into the Pistols’ back catalogue, was purely a money making exercise or the old punk proving he’d still do anything to wind-up the cognoscenti, doesn’t really matter; while it added little to his reputation, Lydon’s never been one to worry over such trivialities.

At least he’d later decide to do the old tunes properly, alongside those with whom he’d written them, and this time wouldn’t have any hesitation in letting everyone know they were in it for the bread. The ‘Filthy Lucre Tour’ in 1996, illustrated far better what Johnny Lydon was all about than anything else he’d been involved in since the middle of the 1980s, and when the opening salvo on certain nights began, ‘We’re reunited for a common cause – your money’ the old fellah was back, witty as ever, and, with his fellow Pistols, breathed at least a little new life into the songs that had changed music forever. It was galaxies away from the cutting edge achievements Lydon had been pivotally involved in between 1976 and 1983, but this didn’t mean it was not worthy. The ultimate show, performed on Lydon’s home turf in Finsbury Park and with support from all manner of other punk credibles, from Iggy Pop to Buzzcocks, was part nostalgia trip, part punk celebration – but a marvellous time was had by most, so what the heck. Another show on the same tour, caught by 1990s visionary maverick, our very own Alan McGee, prompted the great man to take out full page ads in all the music weeklies, at 50 grand a throw, expressing how affected he was by witnessing, after all this time – this was McGee’s first experience of the band live – the group and the singer that inspired him to go out and do something for himself. And lest we forget, Alan’s a PiL first, Pistols second kind of chap.3

The second set of reunion shows in the summer of 2002, punk’s own silver jubilee, or more accurately that of ‘God Save The Queen’ – the subject of which was herself busy celebrating 50 big ones on the throne – passed without the fanfare of the first return. After telling the crowd he hoped they’d missed warm up act The Cure, the antichrist of yore tossed a seemingly quite genuine ‘God-bless’ to those half filling Crystal Palace sports ground, before the band launched into an all but Xerox copy of Hawkwind’s ‘Silver Machine’ – eventually segueing into ‘God Save The Queen.’

Lydon’s recent TV appearances, and his more general return as media guru, didn’t come as much of a surprise – he wasn’t ever going to grow old gracefully. Accusations flew once more from quarters that will never learn. Would this man do anything to keep himself in the public eye and his bank accounts topped up? Well of course he bloody would, it beggars belief anyone still thinks he wouldn’t do anything that pleases him. He can hardly ‘sell out’ from something he’d never bought into.

Johnny Rotten was a stage name, the Sex Pistols were a vehicle, and Public Image, although probably where he felt most at home musically, was just his most focussed outlet. But all that was more than 20 years ago; Johnny still fascinates and bewilders and continues to move in mysterious ways. The character behind all these guises was connected to them by his very soul: John Lydon defines ‘punk’ far more accurately than ‘punk’ defines John Lydon. The dictionary definition of the term; ‘A young person, especially a member of a rebellious counterculture’, goes little further than a most rudimentary, albeit well recognised, description. An online encyclopaedia entry includes, ‘For many still has an unpleasant taste’: now that’s more like it.

John Lydon never did buy into punk; he didn’t have to, he exemplified it; it was created in his image. What became the punk-rock movement, the one he came to detest, is a separate issue. But he has remained a punk in its wider context – a context he was responsible for widening – throughout. He is not just the focal point for the music, theatrics, and cultural legacy, he is the epitome of its spirit.

In 2002, The Ramones were invited to attend their inauguration into America’s Rock’n’Roll Hall Of Fame, an institution that celebrates all those the judging committee consider have contributed sufficiently to that genre of music. With Joey already passed away the previous year (Dee Dee died 2 months after this event and Johnny two years later), the others attended, received their award, and, in uniform leather jackets and ripped jeans, mingled with dickie bowed music industry types and other artists receiving the same accolade that evening. Pearl Jam’s Eddie Vedder was their presenter. This is not to be criticised. The band has surely paid its dues. They’ve gone through hell and back, made some great records, played more shows that The Grateful Dead – without all the hoo-ha – and remain an inspiration to many – they deserve a little backslapping once in a while.

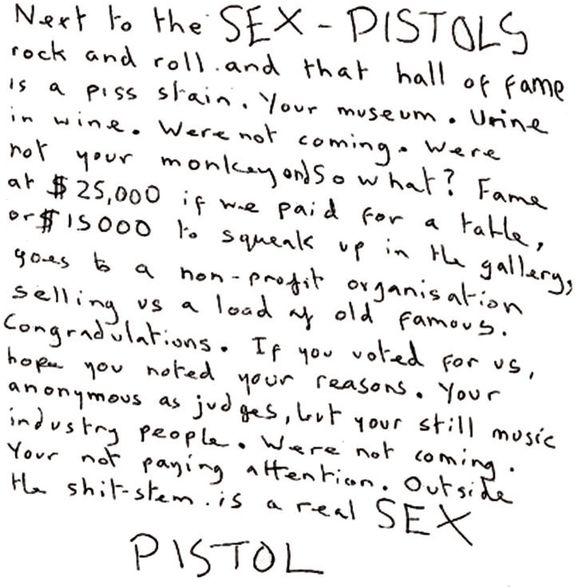

The Sex Pistols were offered a table at the 2006 event; whether they liked it or not they were being sucked into the fold. They were expected to show up around 4pm, drinks and dinner would follow. From here, after perhaps a small but not unexpected incident when Steve Jones, always the joker, lobs a bread roll in the direction of an earlier inductee, and follows it up with a bawdy, unsophisticated comment to an attractive female record company employee wearing a low-cut evening dress, the band hear themselves described in terms of achievement and influence, and are then expected to cheerily, if a little sardonically, approach the stage. Shaking the hands of those introducing them – perhaps a bear hug is appropriate if any of them has previously been introduced to the presenter – they move towards the microphone with traditional belligerence. The audience love them for it. When aired on television, the odd bleep to cover something Johnny was shouting at the back, would signal to viewers these boys have lost none of their old cred, as one by one they give a monosyllabic ‘cheers’ before returning back to their table, good-naturedly mock-wrestling one another for whatever fine statuette is deemed appropriate to welcome this ‘sensational’ group into the academy. Further hugs, kisses, and back slapping would be expected from loved ones and others sharing the night’s festivities with the group. Somehow it makes it all feel worthwhile.

Cook, Jones, and Matlock would probably have gone if Johnny had agreed. They may have attempted to persuade him; the costs were on the high side but, hey, everyone else shows up; The Ramones aren’t rolling in it either. If they had all attended, Lydon would have an explanation as to why, and it’d likely be a good one. But the letter opposite, in his very hand, proves – without slight on those from other bands, or indeed his own – that John Lydon’s dignity is in place.

John Lydon is easy to criticise and there’s plenty of material to choose from. Not a man of clemency or tolerance, he can be unkind, without empathy or courtesy and, often, a royal pain in the arse. But his downside is generally limited to spoken criticism usually delivered with some sense of amusement. And for every tongue lashing there’s a Johnny style compliment; for every condemnation of others there’s one directed inwards. He can come across as an egomaniac in print, but his autobiography often reveals a man of unassuming character, absolute loyalty, and self-mockery. He never wanted to change the world but if he made a few people think in a different way some of his ambition has been realised. John Lydon is impossible to categorise, but that seems to be the way he likes it; he’s the ultimate punk only because there’s no other word fit to describe him.

Rob Johnstone, July 2006

Notes:

The opening line in the first proper study of post-punk and its ‘New Pop and New Rock’ cousins, Simon Reynolds’ Rip It Up And Start Again: post punk 1978 – 1984 (Faber & Faber, 2005), is ‘Punk bypassed me almost completely. ’ The author explains that this was due to his tender years when the first wave exploded.

Despite having been involved in punk - as this book has already confirmed he was an early member of The Clash – Keith Levene’s ’s major musical inspiration was, in addition to the same style of reggae as Lydon and Wobble, the music of the much derided Yes, and particularly their guitarist Steve Howe, whose lines he would practise along to as his contemporaries did to those on The Ramones’ debut. And let’s not forget Lydon’s own admiration for all things Van Der Graaf Generator, part of Prog’s second, if less self-obsessed, league.

Alan McGee’s second independent record label, Poptones, is of course named after a track from Metal Box. His first, Creation, after the band the Sex Pistols were introduced to by Malcolm McLaren, and whose ‘Through My Eyes’ they would occasionally perform live.