|

INTRODUCTION |

After having worked well over 35,000 hours in strategic analysis, I believe the single question I’ve been asked most frequently has been: “What should I look for when I want to recruit my own strategic analysis staff member?”

The question always left me a bit embarrassed, even when I delivered some off-the-cuff answer. I felt I never had a single authoritative source I could point to in response to this question. And so, I decided to give this some serious thought, seek out inspirational new sources and, in this final chapter, synthesize my conclusions. Among other things, I combed through public domain sources from the world of strategic intelligence. This proved helpful, as there is overlap in the nature of their task-work, and thus the required experience, skills and abilities. With this chapter I share the well thumbed logbook of a practitioner’s voyage of discovery. Think of it as a meta-analysis of strategic analysis.

GOOD PEOPLE MAKE ALL THE DIFFERENCE

Strategic intelligence thought leader Sherman Kent wrote this in the 1960s (Heuer, 1999m):

“Whatever the complexities of the puzzles we strive to solve and Whatever the sophisticated techniques we may use to collect The pieces and store them, there can never be a time when the Thoughtful man can be supplanted as the intelligence device supreme.”

The 1960s saw the start of widespread computational support for business analysis. Fifty years later these computational tools have improved beyond what anyone could have imagined. The analyst, however, is still the determining success factor in strategic analysis. No matter how advanced the computer technology, I dare to predict that solving strategic analysis problems will forever require a human touch. Having said that, we continue to search for the right mix of human skills and attributes – the secret sauce that produces the very best strategic analysts.

In this chapter I will first break down the functional competencies an analyst must possess. I’ll lay out what an analyst needs to physically do in the workplace, on a day-to-day basis, and the competencies necessary to effectively perform those duties. We’ll also look at the ideal (or, at least, desirable) behavioural profile an analyst should embody. Based on these two dimensions – cognitive skills and behavioural traits – I’ll then attempt to map out the characteristic and abilities needed for sequentially higher levels of strategic analysis work. These are summarized in an intermezzo at the end of this chapter.

|

FUNCTIONAL |

INTELLECT IS IMPERATIVE BUT NOT ENOUGH

A strategic analyst is a knowledge worker and a professional. Academic training and credentials are critical to a professional’s success. Analysis involves seeing real patterns and signals where others only see randomness and noise. The fewer pieces an analyst needs to solve a puzzle, the better. After all, in strategic intelligence, as in business in general, reliable puzzle pieces are by definition in short supply (Heuer, 1999o):

“This ability to bring previously unrelated information and ideas together in meaningful ways is what marks the open-minded, imaginative, creative analyst.”

In the world of military intelligence, the best intelligence professionals take counter-intuitive thinking as an article of faith (Grey, 2016g). An analyst thus at all times has to be intellectually and psychologically able to recognize and fight the all-to-human tendency to look for confirmation of their existing beliefs, and in doing so turning a blind eye to change.

In strategic analysis, the decision-maker/customer focuses all too often on content and the subsequent decisions that will be made based on that content. It is, however, the analyst who collects the data efficiently and subsequently unlocks insights lurking in that data. When the legendary R.V. Jones, who successfully ran the British scientific military intelligence practice during the Second World War, was asked to write his operational plan in 1940, he included this (Jones, 1978e):

“The size of the staffs […] should be kept as numerically small as possible, and that quality was much the most important factor.”

Admiral John Godfrey, the head of British naval intelligence in the Second World War, in the same context stated (Macintyre, 2010g):

“It is quite useless, and in fact dangerous to employ people of medium intelligence. Only men with first-class brains should be allowed to touch this stuff. If the right sort of people cannot be found, better keep them out altogether.”

It is easy to dismiss the above two quotes as dating back to other times, situations and needs. The world of the business decision-makers that strategic analysis serves today, however, still seems to be governed by people competing with each other. This after all is also Clausewitz’s definition of war. Parallels between the intensity of 1940s wartime efforts and today’s cutthroat global competition may well be drawn. For those in business who fail to outsmart through superior analysis, through smarter strategies and through (most of all) better execution, the threat of formidable, costly, head-on competition looms large.

There is a catch here. Intellect should not be overrated. After all, intellect as measured by IQ matters only up to a point (Gladwell, 2009a):

“Once someone has reached an IQ of somewhere around 120, having additional IQ points doesn’t seem to translate into any measurable real-world advantage.”

Once an analyst meets the threshold of about 120 IQ points, success or failure are largely determined by behavioural traits. It is for this reason that most of this chapter has been dedicated to behavioural competencies that can contribute to an analyst’s success.

IMAGINATION AND ANALYSIS RARELY GO TOGETHER; CREATIVITY MAY BE IN-SOURCED

Too often a lack of imagination has been the root cause of (military) intelligence failures. The best analyst xenocentrically not only understands what a competitor has done in the past but also why. The analyst also can imagine what the other party will (most likely) do next. Imagination is not an analytical skill. It is a creative skill. Imagination does not correlate with analytic skills in people; the skills are orthogonal (Gladwell, 2009b). When a strategic analysis department head has to choose between a candidate with an IQ of 150 who exhibits low creative skills and one with an IQ of 120 but extraordinary creative skills – all other things being equal – the latter individual is the obvious choice.

When there is a distinct lack of imaginative thinking in a strategic analysis department, dare to acknowledge this internally. Where necessary, address this shortfall by in-sourcing creative talent to complement the rest of the staff’s skills and experience in a particular assignment. Provided these staff get the right briefing and context, the freelance creatives may imagine a competitor’s next moves in a way that rigid, run-of-the-mill analysts may fail to see. Strategic analysis departments should have a tolerance for individual eccentricity. In reviews of the success of the British Second World War code-breaker units in Bletchley Park, the eccentricies of a large number of extraordinarily bright staff features again and again as a critical factor.

RESEARCH SKILLS ARE A HOUSEKEEPING MATTER

An analyst’s research proficiency is a basic matter of business skills hygiene. Profound knowledge of disciplines such as mathematics (especially statistics), experimental design, where applicable physics or chemistry or another science specialty may round out an analyst’s research toolkit. This is not to say that anthropologists, students of law, historians or economists can’t develop into good analysts. They very well might, providing they develop a sufficiently strong understanding of quantitative methodologies that reside at the core of strategic analysis.

BUSINESS ADMINISTRATION KNOWLEDGE HELPS WITH UNDERSTANDING THE CONTEXT

In serving senior executives, mastery of the language of business management is essential. An analyst should be well versed the classics of business strategy. Understanding company financials goes beyond knowing the difference between the top and bottom line of a profit and loss account. It includes grasping the meaning of footnote 34 to a balance sheet that appears on page 527 in a company’s information memorandum.

The small print in a competitor’s report often brings the greatest joy to a curious analyst: that’s where an illuminating link has been buried that may tell the company’s real story.

LANGUAGE SKILLS ASSIST IN TAKING A XENOCENTRIC VIEW

Language skills have long been highly valued as intelligence collection and analysis assets (Deacon, 1982c). In collection, mastering the language of a competitor’s documents is of immediate value – even when tools like Google Translate have made an analyst’s life a bit easier. In personal face-to-face contact, mastering another party’s language is even more important, as sharing a language usually increases trust and breaks down barriers. Understanding a competitor’s language in analysis assists in better grasping the competitor’s culture and through the culture its possible and impossible next moves. It can also help an analyst assess a competitor’s culture, and its predisposition toward certain tactics and strategic moves. Literary critics were among the most effective British and American counter-intelligence officers in the Second World War (Johnson, 2009d):

“(they were) trained to look for multiple meanings, to examine the assumptions hidden in words and phrases, and to grasp the whole structure of a poem or a play, not just the superficial plot or statement. So the multiple meanings, the hidden assumptions, and the larger pattern of a counter-intelligence case were the grist for their mill.”

A multilingual analyst is for most international companies a valuable asset.

CONCENTRATION AS A VIRTUE

An overwhelming amount of noise (or, as it is also known, information overload) is linked to attention fragmentation (Dean, 2011). Attention fragmentation is to be avoided. It is detrimental to analytic thinking, learning and the quality of decision-making:

“[Uninterrupted time is needed] to synthesize information from many different sources, reflect on its implications for the organization, apply judgment, make trade-offs, and arrive at good decisions.”

An analyst with a natural ability to concentrate has a distinct competitive edge in her profession.

For an analyst, a basic mastery of consultancy skills is imperative; it is a basic housekeeping matter. Consultancy skills, for example, include:

• Process management, including managing for stakeholder acceptance of deliverables.

• Storylining and slide writing, including mastering visualization tools.

• Communication skills: including situational application of various approaches (tone, content, medium, timing, etc.).

An analyst, however, is not by definition a good consultant, and vice versa. An analyst is first and foremost a subject matter expert, focused on creating timely, accurate, high-quality deliverables. It goes without saying that the deliverables should be accepted by executive decisions-makers; otherwise they’re essentially worthless, academic exercises. Gaining executive acceptance of your hard work is where consultancy skills come in most handy. When strategic analysis is part of a corporate strategy department, the analyst and the strategy consultant will likely team up to ensure both quality and acceptance.

For an analyst who operates in a solo capacity and does not have the luxury of working with a consultant peer, consultancy skills that are often tightly interwoven with communication skills are even more relevant (Davenport, 2014c).

|

BEHAVIORAL |

CURIOSITY IS ESSENTIAL FOR AN ANALYST TO SUSTAIN JOB SATISFACTION

It is hard to overrate the relevance of curiosity as an attribute in a good analyst. In English strategic intelligence in the Elizabethan Age (second half of the Sixteenth Century) Sir Francis Walsingham – who led the equivalent of MI6 in his time – is reported to have said in defense of his work (Alford, 2013b):

“I protest before God that as a man careful of my mistress’s [i.e. Queen Elizabeth I] safety I have been curious.”

This wording is truly elegant. In Alford’s estimation the value of the word curious can hardly be overstated:

“This was a masterful piece of wordcraft, for though ‘curious’ meant in one sense attentive and careful, it also gave a meaning of something hidden and subtle. After many years of fighting a secret war against an unforgiving enemy, Walsingham captured his profession in a single adjective.”

Walsingham in this respect is an example to any analyst in the Twenty-First Century. True analysts should be as passionate as Walsingham was to want to know everything about their competitors. The tagline for a strategic analysis department may well be ‘We know it all – or else we know how to get it’.

This passion for knowing goes beyond the search for knowledge for the mere sake of it. There is a remarkable confluence of interests in a company’s and an analyst’s shared urge to satisfy burning curiosity. Through obtained fact and knowledge-based analysis, the company will benefit from solid market intelligence as input to value-creating strategies. At the same time, the analyst benefits emotionally from what an extra puzzle piece may bring (Moore, 2007b):

“Successful intelligence analysts are insatiably curious. Fascinated by puzzles, their high levels of self-motivation lead them to observe and read voraciously, and to take fair-minded and varied perspectives. This helps them to make the creative connections necessary for solving the hardest intelligence problems. Finally, the emotional tensions created by problems, and the cathartic release at their solution, powerfully motivate analysts.”

TOLERANCE FOR FRUSTRATION IS THE HALLMARK OF ALL RESEARCHERS

They also know that, more often than not that release never comes. At times, issues appear that look like puzzles but happen to be mysteries. On these occasions, the analyst does not solve the mystery, a solution is not at hand… and the analyst comes away understandably frustrated.

We’re not going to try to identify all possible frustrations that an analyst can encounter in her daily work. That would be too depressing. We will take a look at two common sources of frustration that arise with some frequency. A natural ability to handle both is a critical strategic analyst competency, so I’ll briefly touch on how to manage them.

The first such annoyance is the simple lack of sufficient data to solve a puzzle in a timely manner. This frustrations may have two root causes: time is too short (given the resources available) or the issue is too unfamiliar. In such situations surfacing and focusing on the critical issues is the best approach when handling assignments under intense time pressure. When data available for analysis lacks solve the critical issues, the only option left is to acknowledge that you’re unable to solve the mystery, admit defeat and to stick to situation reporting. No matter how unsatisfying that may be, it is the analyst’s role and obligation to be totally open with the principal about what is known and what is not known. The analyst must then shake off the sting of a missed deadline and advise the executive of when the next data are expected to arrive, and how you can all re-set for the now-delayed decision/action.

A possible second source of frustration is that the market intelligence developed is high grade, but management’s reaction was lukewarm at best. To make matters worse, the decision-maker may not take timely action on your recommendations, or ultimately never take any action whatsoever. This does not only happen in the business world, as these cynical and frustrated remarks by former US intelligence analyst Robert S. Ames makes clear (Bird, 2014):

“You have this notion that all you need to do is get the right facts before the policy makers – and things would change. You think you can make a difference. But gradually, you realize that policy makers don’t care. And then the revelation hits you that U.S. foreign policy is not fact-driven.”

A strategic analyst who feels the need for action following a task, as a basic requirement for job satisfaction, has sadly chosen the wrong job. In this profession, the analyst simply must learn to keep dissatisfaction at bay when things that are clearly beyond his control go cockeyed. In this field, anyone who’s susceptible to being badly shaken by things he can’t control is at risk of a range of psychological problems. When recruiting an analyst, look for some who’s thick-skinned, rolls with the punches and knows how to choose his battles.

PERSUASIVENESS

It is not always the other guy’s fault. The analyst always has to look how she can improve in her performance. This starts with realizing that even high-grade intelligence needs to be persuasively communicated. The following example puts a sharp point on that.

In the early 1970s Henry Kissinger was National Security Adviser to US President Nixon. At some stage an intelligence analyst offered him new, high-grade intelligence. Kissinger did not act upon it. When the intelligence later proved to have been correct, Kissinger is reputed to have said to the analyst (George, 2008b):

“Well, you warned me but you did not convince me.”

The message here is simple. Look for an analyst who not only delivers a prescient report, but also can compel the recipient to promptly and thoughtfully act upon it. The recipient may still choose to do nothing, but at least he gave the report appropriate consideration. It was not unfairly discounted.

HUMILITY

An analyst must be confident and persuasive but must never tip over into arrogance or start talking down to the principal. The analyst’s ego must be checked at the door (Lauder, 2009). Strategic analysis serves the senior business leader. Anyone out there who goes into business out of a desire to lead and decide, rather than discover through collection and analysis, should consider becoming something other than a strategic analyst. When looking for an analyst, avoid hiring a person with a strong people power need.

PERSEVERANCE

At times analysis work requires sifting through large amounts of random information in search for some illuminating links (Wolf, 1998). If ever a job required stamina and perseverance, it is data collection and analysis. An individual seeking employment in the analysis game should have the word perseverance underlined on her resume.

From the company’s standpoint, this persistence and determination do not come free of charge. Perseverance links to time spent on an issue. For a firm that over time hopes to develop knowledge of its markets and business environment to increase its competitive edge and deliver value, investing in go-getter analysts will yield high returns provided… a critical condition is met. Namely, the output of the strategic analysis department should seamlessly inform corporate (strategic) decision-making. When recruiting an analyst, look for an individual willing to go the extra mile, but who remains focused on getting the better decision taken.

TENURE IS NEEDED TO BUILD UP A LIBRARY OF PATTERNS…

Strategic analysis is a craft, not a job. It is a specialist capability that one needs to extensively practice and gradually master. Implicit in the idea of craftsmanship is the notion that a young apprentice will be guided/coached by a senior craftsman in learning the trade, ideally on the job (Cooper, 2005b). This organizational model equally applies in business. Once mastering a craft, it does not need to be practiced for many years and still will not be lost. Javers points to Vladimir Putin, who as president of the Russian Federation remarked in 2005 (Javers, 2011a):

“There is no such thing as a former KGB-man.”

This statement, absent the dark pride that is concealed in it, also applies in strategic analysis. Once an analyst, you will always remain one. Even after many years of doing different jobs, a person that has worked as an analyst still instantly will recognize strategic patterns, still will view data presented with a healthy skepticism and will still by default double-check superficial conclusions.

Former CIA Director Allen W. Dulles once told Congress that intelligence (Robarge, 2007):

“…should be directed by a relatively small but elite corps of men with a passion for anonymity and a willingness to stick at that particular job.”

The willingness to stick at a particular job is critical to the process of learning a craft. Sticking at the job is therefore imperative if one hopes to become truly good in strategic analysis. Being an analyst is one of those professions where the so-called ‘10,000 hour’ rule applies. The idea is that a person requires 10,000-hours of concentrated practice before true excellence in a craft can be achieved (Gladwell, 2009c):

“In study after study, of composers, basketball players, fiction writers, ice skaters, concert pianists, chess players, master criminals, and what have you, this number [10,000 h] comes up again and again. […] No one has yet found a case in which true world-class expertise was accomplished in less time. It seems that it takes the brain this long to assimilate all that it needs to know to achieve true mastery.”

The 10,000-hour rule undoubtedly applies to strategic analysis. The importance of an analyst building up a library of patterns for future reference and instant pattern recognition is critical (Heuer, 1999b). Tenure is the only way in which to build up such a library (Klein, 1999d).

More recent research confirms this view. Researchers conducted a geopolitical forecasting tournament, assessing the accuracy of more than 150,000 forecasts from 743 participants (all of them analysts) relating to 199 events occurring over two years (Mellers, 2015). The key finding was that the best forecasters were:

• Better at inductive reasoning.

• Pattern detection.

• Cognitive flexibility.

• Open-mindedness.

“…viewed forecasting as a skill that required deliberate practice, sustained effort, and constant monitoring of current affairs.”

When selecting an analyst, look for individuals who see analysis as a career, not a job where second-guessing and doubt – particularly haunting doubts about one’s own conclusions – are daily companions.

…BUT TENURE HAS ITS RISKS AS WELL

There are two common downsides of long employee tenure. First, building up expertise through multiple years of pattern recognition is only possible in a relatively stable or even a regulated environment (Kahneman, 2011n). The stability of the environment is critical. In the absence of stability, the accumulated patterns in the mind of the analyst would not be valuable as building blocks for handling future cases. Such stable work environments include firefighting (where Laws of Nature apply, and chess or poker, where rules are fixed and statistics matter (Klein, 1999d) or possibly in relatively stable industries such as food processing).

The second potential downside concerns sustaining staff motivation. In business, long tenure is sometimes associated with organizational sclerosis: comfortably settled-in employees who do just enough to get by and who may resist innovation and change. Convincing research, however, shows that (McNulty, 2013):

“[…]high [business] performance standards can keep people motivated for decades.”

Strategic analysts almost by definition set high performance standards for themselves; that is the true nature of the beast. Rather, analysts too often tend to be overly perfectionist. Tenure in strategic analysis, in a relatively stable industry setting, is therefore an asset by any measure.

COURAGE

An analyst needs at times to be prepared to challenge the status quo by boldly expressing original thinking, and going to the mat to defend those ideas. Yesmanship may be an easier approach for an analyst who wants to retain his credibility and his reputation for objectivity. Respectfully but persistently sticking to a well-substantiated analytic conclusion that may not be entirely popular with a company’s leadership requires courage. Analysts should have such courage, trusting their intellect and their employability.

Courage is not universally defined. It differs by culture. Assuming a respectful but challenging position with a decision-maker may be common and perfectly acceptable in some cultures, whereas in others exactly the same behaviour may considered bravery. The Dutch psychologist Geert Hofstede suggested a quantitative yardstick to measure attitudes toward hierarchy. He called this indicator the ‘Power Distance Index’. The ethnic theory of plane crashes is based on this work (Gladwell, 2009c). The more a culture values and respects authority, the larger the Power Distance Index and the more courage it takes to speak up to authority. In cultures in which speaking up is not the norm, plane crashes occur more frequently, because flight crews don’t offer up their own observations, suggestions and warnings, relying instead entirely on the exalted pilot. Don’t emulate the airline with the tight-lipped crew when hiring strategic analysts; look for those who are willing to speak up when they need to.

BEYOND COMPLIANT

Strategic analysis staff relate to spies as shop customers relate to shoplifters. Spies are at times assigned to steal information, whereas analysts are assigned to legally collect and process information. An analyst who duly shops and pays for the goods acts ethically and legally. A scoundrel who goes to the shop and takes the goods without paying clearly does not. A collector or analyst – often the same person in a business setting – must possess a natural inclination to steer clear of ethically (let alone legally) shady practices. An analyst who can’t suppress the urge to steal cannot be hired to do your shopping.

SYSTEMATIC

An analyst must not be chaotic. Markus Wolf, quoted earlier, emphasized that in intelligence work, the analyst searches for illuminating links in a set of seemingly random data. Doing so requires a systematic approach to data management – both in an individual’s work and in a strategic analysis department.

QUALITY FOCUS

An analyst needs to be able to balance intrinsically conflicting factors in his work. For instance, there are always more questions than resources to answer the questions. An analyst must sense why some work deserves more priority and more effort than other work, intuitively linking the work to the urgency and relevance of having the answers available to the firm. Quality starts by doing the right work.

Quality also requires doing the work right. Good analysis work has three attributes: it is timely, accurate and complete. All three attributes together make up the quality of the work. An analyst needs to manage dilemmas that may occur when timeliness cannot be sacrificed, even when a deliverable is neither accurate nor complete.

An incomplete and inaccurate assessment, however, may do more harm than good. Hire the analyst who can figure out how to navigate such conflicts, even when best choices may differ case by case.

EMPATHIC – XENOCENTRIC – SOCIABLE

An analyst who doubles as a collector requires the skills specifically required for collection. Especially for collecting data from interviews, sociability is a plus. What truly matters is that an analyst has a fundamental interest in people. Strategic analysis is a craft that sources skills from multiple disciplines. Having a quantitative analyst with a passion for anthropology may be rare, but may just be what an analysis department needs. Xenocentrism cannot be executed through filling out and filing spreadsheets only.

DISCREET

An analyst should set out to gradually develop a trusting relationship with her senior executives. Over time, through those high-level relationships, an analyst may become privy to a company’s secrets as well as get a sharper view of the personal needs and vulnerabilities of its decision-makers. Developing such insights will greatly enhance an analyst’s effectiveness. To become a trusted advisor to senior leaders, one must also exercise discretion. Bragging to peers or subordinates about what friends in high places have confided is a critical mistake.

INNOVATIVE AND CHANGE-ORIENTED

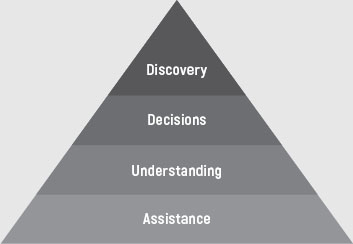

The analyst profession over time has changed and it continues to change, requiring the analyst to be innovative and at times to lead change. An analyst can be seen as a violin player in a symphony orchestra, with the decision-maker being the audience and the strategic analysis department head (or the head of strategy) being the conductor. Gradually, however, the analyst role in parallel also evolves into that of a conductor of his own orchestra, with his own players being computers and models. See diagram 21.1 , on analyst-computer interaction (Edward, 2014).

At the bottom of the pyramid is level one – assistance. Any analyst uses the computer as a channel to the Internet, for assistance, as an on-demand encyclopedia encompassing the knowledge of humanity. Nothing new or innovative here: using a computer in an assistance role is a basic, underlying necessity for functional competency.

‘UNDERSTANDING COMPUTERS’ AS A CURRENT BACKBONE SUPPORT TOOL

Level two is called ‘understanding’. At this level, behavior skills matter at least as much as functional skills for the analyst. In strategic intelligence, no analyst can dream anymore of reading all available materials by himself (Medina, 2008). Collection is so cheap and data are so abundant that making sense of it all becomes a bottleneck. Moreover, the information avalanche is such that a single expert cannot cope with it.

There are two ways to cope with this challenge; each involving a behavioral innovative skill of an analyst. The analyst has to feel comfortable to:

• Work in teams and divide the workload, even when doing so is resource-intensive.

• Program computer algorithms to spot (combinations of) key words, to filter critical data and information pieces out of the clutter (Natural Language Processing).

The latter approach is by its nature no longer the traditional, anecdotal form in which data reach an analyst’s desk. Rather, it is holistic. The output is not a single story on an issue but it may reveal patterns and patterns may, for example, reveal social media attention to an issue. To return to Markus Wolf’s search for illuminating links: in his former East German life, filing cabinets with hardcopy cards were needed, with the card being appropriately coded with metadata in multiple dimensions. In today’s world, a single well-defined search algorithm may generate an inflow of potentially relevant news stories to a strategic analysis department, with the computer having read and understood thousands of clippings daily. Today, the computer finds the links and the analyst’s role is to focus on making sense of these links.

INTELLIGENCE MAY NOT MATCH WITH AUTOMATED DECISION-SUPPORT SYSTEMS

Level three is called ‘decisions’, which is shorthand for direct decision support. An example would be analyst-computer interaction using expert systems that assess patient x-rays and based on the assessment suggest treatment options to a medical specialist. The computer algorithm is based on accumulated learning of medical professionals on things like bone fractures. What are typical cues for a typical type of fracture? What evidence should be present and what should not be present? The medical specialist, in making a judgment on what is seen and by implication what to do, not only uses his own accumulated library of mental bone fracture cases, but in parallel may check what his electronic peer recommends. A classic similar example is chess. IBM’s Deep Blue actually beat the chess world champion. What does this level III interaction mean for strategic analysis?

Heuer argues that while analysts may benefit from building a library of business cases, the rules of business or politics are fundamentally different from those of chess or bone fractures (Heuer, 1999p). Chess is guided by fixed rules. Within a wide legal framework, however, business thrives when it innovatively changes the rules. No disruptive innovator after all ever started out complying with all the rules of an existing business model. Attempting to automate direct decision-support in strategic analysis may therefore have a fundamental flaw.

The strategic analyst who one would preferably hire will be wary of trusting expertise claimed in fields that are not governed by natural laws or fixed rules (Taleb, 2007f). This may equally apply to market intelligence and digital decision-support expert systems. Heuer even warns analysts to never put too much trust in their accumulated library: rules that in the past may have applied in politics or in business, may no longer apply. As a result, the patterns the library may be woefully obsolete. Unlearning established patterns may well be harder than coming to understand new patterns. Being eager to engage in an ongoing, open-ended process of learning and unlearning is thus a critical analyst asset.

DISCOVERY IS ALL AROUND US

Level four is called ‘discovery’. Discovery is making a computer algorithm look for connections that nobody knew existed. This is a capability that is under rapid development. Retail chains using bonus card systems may discover patterns in human in-store behaviour that even the shoppers themselves may not consciously know they’re exhibiting. This applies both to classical brick-and-mortar retail and probably even more so to online retail merchandising. Every click can be measured, reflecting often implicit human behavioural patterns. When either through a bonus card database review or through on-line site interaction analysis a pattern is discovered, the retailer that capitalizes on it has an opportunity to deliver better offerings to its customers. As the dynamic unfolds, the seller’s offerings map increasingly well to a customer’s individual (sometimes unconscious) needs, desires and buying patterns. The retailer gains a bigger share of the customer’s spending and more profits, allowing it to further optimize its buying pattern analysis and targeted selling, etc. This is where Big Retail may turn (or is turning) into Big Brother. This technology is ready, it’s out there, and is being applied. Algorithm-oriented data analysts who feel ethically comfortable using their brains to work in this sub-section of data processing will likely find ready, willing and eager employers.

|

STRATEGIC ANALYSIS |

When recruiting strategic analysis staff, behavioural competences – from curiosity to courage to compliance – matter most once a candidate demonstrates a certain baseline level of intellect. Intellect and experience are independent of one another (Klein, 1999e), but both matter in selecting an analyst. In a craft like strategic analysis, practiced in a more or less stable environment, experience matters because a library filled with relevant patterns will enable much faster and generally better decision-making. The ideal analyst has both a sufficiently high intellect, at least the beginning of an experience-based library with relevant patterns, and the willingness to (over a longer period of time) continue in to trade enrich that library. A twist of eccentricity in an analyst may be indicative of a creative spark that enables her to find the unconventional, creative solution to a strange new puzzle. I believe the quote below sums it up, matching my personal experience and that of some of the brightest analysts I’ve had the privilege to work with over the years (Freedman, 2013f). Strategic analysis is:

“…the domain of the strong intellect, the lifelong student, the dedicated professional, and the invulnerable ego.”

I hope I’ve effectively portrayed strategic analysis as a craft that has rightfully earned its place as a valuable functional discipline in the world of business. We’ve seen how, from their origins in the military and government, a wide range of data collection and analysis methodologies – applied with a bit of effort and a little imagination – can make a real difference in the world of business. For those of you embarking on a career in strategic analysis, it is my hope that these observations and insights will help send you on your way, and enrich your experience as you live and learn this fascinating trade. For those seasoned, long-term practitioners among you, I hope my thoughts and advice will ring true and complement your own experience, skills and expertise. Above all, I sincerely hope your endeavors in this field bring you the same sense of fulfillment and pleasure I’ve felt through my long career as a professional strategic analyst.

INTERMEZZO: SKILLS AND ACCOUNTABILITY

For both the individual analyst and the broader strategic analysis department, functional and organizational accountability is spelled out in Table 21.2 and 21.2:

|

ACCOUNTABILITY |

KEY ACTIVITIES |

RESULTS |

|

Functional - Collection - Analysis - Reporting - Delivery |

- Set up network of sources - Develop standard methods/views - Produce ad-hoc & periodical reports - Periodic presentations to management |

A xenocentric view on the business environment: - No relevant ‘missed’ news - Set of analysis tools/practices - Periodical & ad-hoc deliverables - Embedded output in decisions |

|

Organizational - Budget - Staff - Training/tools - Work portfolio |

- Set up annual budget for strategic analysis discipline - Recruit and train balanced team - Define training in portfolio/tools - Manage time/resources/budget |

A department delivering output that management acts upon - Clear cost/benefit overview - Motivated, professional team - Portfolio ready to use for projects - Accurate, complete and timely output |

TABLE 21.1 FUNCTIONAL AND ORGANIZATIONAL ACCOUNTABILITIES OF ANALYST/DEPARTMENT

|

COMPETENCY DESCRIPTION |

|

|

1. |

- Able to collect basic competitive data (news, launch announcements, background on products, customers, suppliers, etc.) - Able to clearly report key findings in response to a given management brief - Able to understand and use basic economic data (GDP, etc.) - Grasps the importance of and ensures secrecy - Has basic interaction/communication skills |

|

2. |

- Able to periodically update and where needed proactively inform senior mgt. on key developments in the your company’s business environment (facts only) - Able to superficially analyze several separate facts to prepare a bigger picture view for decision-makers - Able to directly liaise with outside information suppliers (AC Nielsen, Planet Retail, etc.) when directed to do so - Able to understand basics of business strategy theory - Able to understand own firm’s strategy and business drivers - Has well-developed reporting and persuasive communication skills |

|

3. |

- Able to collect all data and map a competitor, using a pre-defined format, through desk research, including analysis of competitor’s perceived strategy and assessment of possible implications for your firm’s strategy execution - Able to independently manage a portfolio of assignments and set priorities matching business needs and upside potential - Able to (and trusted to) network with competitors, customers, etc., remaining wary of their attempts to elicit intelligence on your company - Able to capture HUMINT; knowing the basic HUMINT rules - Able to organize and [periodically] run ‘competitor review‘ workshops to collect, analyze and codify ‘tacit business environment information’ - Understands need for full compliance with applicable laws and ethical considerations - Able to explain and convince stakeholder beyond content-driven arguments; understands and applies xenocentric view |

|

4. |

- Able to execute tailored, self-defined collection and analysis missions, even in new markets, new geo-areas (incl. interviews) - Able to understand own firm’s corporate strategy – brands and supply chain – and implied unit choices and options; credible MT sparring partner - Able to write full ‘business environment analysis‘ chapters for strategic plans, budget books, acquisition or investment plans - Able to independently innovate collection and analysis methodologies; must have state-of-the-art knowledge of best practices and track record in applying various collection and analysis tools; recognized expert in the field - Able to train/educate/coach and manage junior staff where needed - Able to raise secrecy awareness and persuade management to employ counter-intelligence initiatives - Able to proactively generate M&A proposals based on business environment trends; liaise with investment banks/lawyers on M&A teams - Able to embed xenocentric view in strategic analysis - Able to enforce full compliance with applicable laws and codes of ethics - Able to persuade based on content and personal reputation/track-record - Has courage to report news and analysis that goes against the party-line. |

TABLE 21.2 FOUR STRATEGIC ANALYST COMPETENCY LEVELS IN A SEQUENCE OF INCREASING COMPLEXITY/JOB RANK