cooking from the

Italian

garden

Eggplant and the herb nepitella are classic Italian ingredients. Here (left) the eggplant has been grilled and finished with a little nepitella butter.

Italian cuisine is glorious! Considered the “mother cuisine” for much of Europe, it has its roots in ancient Rome. Cabbages, artichokes, broccoli, peas, chard, lettuce, fennel, mint, parsley, melons, and apples, as well as wine and cheese, many kinds of meat, and grains were all enjoyed by ancient Romans. For feasts Roman cooks used many spices, developed recipes for cheesecake and omelets, and roasted all types of meat. From this noble beginning a sophisticated and flavorful cuisine has emerged.

After the excesses of the Roman banquets, at which quantity was more important than quality, centuries of cooks on the Italian peninsula selected the best of the ancient cuisine and continued to pursue the art of cooking. In the late Middle Ages Italian cooks perfected bread making and started making pasta. In the sixteenth century the first modern cooking school was opened in Florence, and from then on cooking has remained a high art in Italy and cooks have continued to explore new ingredients and new ways to prepare foods. In fact, Italian chefs were the first to embrace many of the foods of the New World in the early 1500s. Italians quickly learned to appreciate snap beans, tomatoes, peppers, squash, and potatoes; eventually these wonderful vegetables found their way into much of European cooking.

While most Italians share a somewhat similar basis for their cuisine, the foods in one part of Italy are often quite different from those in another, because of regional differences in history, economics, and climate. (Remember, Italy was but a group of nation-states a little more than a hundred years ago.) For example, in northern Italy cooks use quite a bit of butter and cream. Pasta there often contains eggs and is rolled out into flat noodles. A specialty of Piedmont, near the French border, is bagna cauda, a rich sauce made with cream, butter, garlic, and anchovies. Traditionally, the Piedmontese dip strips of cardoon in bagna cauda, but they also use fennel, cauliflower, and peppers. Near Venice, in Treviso and Verona, the bitter chicories (radicchios) are much prized; they are enjoyed as salad greens or sometimes roasted. In nearby Padua fritters are made with squash blossoms. Vegetables abound in Rome and vicinity, where broccoli is cooked in wine, olive oil, and garlic; little peas are served in spring, sometimes cooked with tiny morsels of prosciutto and served on pasta; and white beans are baked with pork rinds. Most of these dishes would not be found in more southern parts of Italy.

The dishes of southern Italy are, as a rule, more heavily spiced than those of the north, redolent of basil, oregano, garlic, and sometimes hot peppers. The primary cooking oil is made from olives, because butter is not as easily obtained, as cows do not produce well in the hot, dry climate. Sauces are often made with sun-ripened tomatoes and olive oil. The primary pastas are dried and tubular and usually do not contain eggs. A favorite dish of Naples, considered the center of southern Italian cooking, is a sauce for pasta made with tomatoes, onions, garlic, and often some type of meat. A fish soup from Abruzzi contains onions, tomatoes, garlic, bay leaves, and parsley. Throughout much of southern Italy, the favorite vegetables are red peppers, eggplant, tomatoes, spinach, and artichokes.

Over the years, as Italian cuisine has been refined, it has not evolved into one filled with complex dishes, as is common in much of France. Instead, it has remained elegantly simple. Italian cuisine is often described as unadorned and honest; as Waverley Root, food writer, comments, “The apparently simple cooking of Italians is, in fact, more difficult at times to achieve than the more elaborate refined French cooking. Things have to be good in themselves, without aid, to be exposed naked.” In his book The Cooking of Italy, he adds, “Fruits and vegetables must be picked at the right time, neither one day too early nor too late. They must not travel far, must not be preserved beyond their allotted season by chemicals and refrigeration.”

A pantry for Italian cooking (above) would be remiss if it didn’t include extra-virgin olive oil, Parmigiano-Reggiano cheese, garlic, rosemary, tomatoes, and pasta.

Given Waverley Root’s comments, you can see why a garden of fresh, well-grown vegetables and herbs becomes a critical part of truly fine Italian cooking. In addition, since Italian cuisine is so unadorned, not only the vegetables and herbs, but also all the starting ingredients must be the best. When you prepare the recipes that follow, use only the highest-quality olive oil—cold-pressed, extra virgin for both salads and cooking. The Parmesan and other cheeses must also be of the best quality; canned or generic versions obliterate rather than highlight the flavor of your vegetables. Visit a good Italian delicatessen to stock up on superior olives and olive oils, arborio rice, polenta, fontina, and Parmigiano-Reggiano cheeses, and anchovies preserved in salt. These items may seem expensive at first, but you will use only small amounts of these ingredients, and they make a startlingly big difference in your cooking. If you don’t have access to such specialties, there are a number of mail-order suppliers (see Resources, page 103).

Seasonal Dining

Of all the modern cuisines, I find Italian the most married to the garden. The Italian diet is still blessedly seasonal. This truth came home to me the first time I visited Italy, when nearly every restaurant we went to for three weeks in April offered artichokes, spring greens, and peas. There were no roasted bell peppers or pears or snap beans on the menu—the vegetables offered were spring vegetables, period. Further, Italian cooking relies upon a variable harvest. A hurried garden harvest can always produce a fabulous meal. The meals are suited to what a garden produces—a small handful of spinach, a few small heads of broccoli, and the season’s last two carrots would work in a salad, or they could be sautéed and served with polenta or pasta and sprinkled with cheese. Most recipes don’t call for a pound of this and a pound of that; often the ingredients list is fluid.

One final thought: while much of Italian garden cooking strikes us as rustic, or home cooking, in Italian cuisine more than any other, fresh vegetables and herbs can also be haute cuisine. In Giuliano Bugialli’s Foods of Italy, for example, you can find recipes for vegetable compote with dry zabaione, pepper salad with capers, and carabaccia “of the full moon,” made with fresh peas, carrots, and fennel. Bugialli goes on to say, “Vegetables, even more than pasta, are the cornerstone of Italian cooking.” With the produce from your Italian garden, you can now truly create the tastes of Italy.

Melons, tomatoes, onions, and beans from my garden

preparation methods

Vegetables in Italy are cooked in endless ways, befitting their status. They are included in every part of the meal, from antipasto to an occasional dessert.

Antipasto

Translated into English, antipasto means “before the meal,” and it’s associated more with restaurants than with home cooking. While an antipasto can consist of olives, anchovies, sliced meats, and seafoods, many vegetables are served as well. Some of these are white beans with seasonings, sometimes made into a puree and served on toasted bread; roasted red bell peppers served alone or with capers; pickled cherry peppers; thin slices of fennel drizzled with olive oil; chopped tomatoes and basil on toasted bread; and all sorts of vegetables in a tomato sauce. They can be offered in conjunction with other seafood or meat dishes for a party or served singly in a family setting.

Soups

Soups appear to be the “soul food” of Italy. They are generally a hearty mix of vegetables and seasonings thickened with either pasta, rice, or bread. Minestrone, which translates to “big soup,” is this type of soup. There are also soups that feature only one or two vegetables. Meat is rare in an Italian soup; sometimes just a little prosciutto is added for flavor. Many soups are served warm in the winter, and at room temperature in the summer. As a rule, the soups in the north are hearty and fairly filling whereas the ones in the south tend to be lighter.

Vegetables are an integral part of an Italian antipasto. This one includes slightly cooked romanesco broccoli, roasted pimento peppers, sprouting broccoli, and sliced fennel.

Salads

Salads are very popular in Italy. They are most often a simple presentation of lettuces, endive, escarole, arugula, and all sorts of chicories (either alone or in a mixture) drizzled with premium olive oil and salt. Mixed, young, tangy “wild greens” are popular in the spring and are simply dressed with olive oil and salt. Vinegar or lemon juice is sometimes added, as are fresh herbs and, occasionally, garlic.

Pinzimonio is the name of a dressing made with the best possible quality of olive oil and served in a small bowl. Diners season the oil to their taste with salt and pepper and then dip raw vegetables into it, most commonly wedges of bulbing fennel, but paper-thin slices of raw artichokes, sliced radicchio, bell peppers, and tomatoes are also favored. At home, pinzimonio usually features one vegetable, though Italian restaurants often offer a mix.

Another lovely Italian salad is the Tuscan bread salad panzanella. Soak slightly stale rustic bread in water for about five minutes, squeeze the bread with your hands to remove the water, and then crumble the bread into the bottom of a large salad bowl. Over this spread fresh ripe tomatoes, sliced onions, and basil. Pour a dressing of olive oil, wine vinegar, and seasonings over the vegetables, toss the salad, and serve it at room temperature. In some areas shrimp or squid is added to the vegetables.

Side Dishes

Most fresh vegetables are generally cooked in the same manner, whether they are used as the basis of a side dish, say, or added to a pasta dish. A large pot of salted water is brought to a boil and vegetables are cooked until just tender. They are then drained. Leafy greens are then squeezed to remove excess water. Vegetables can be refreshed by warming them in a pan with butter or olive oil just before serving, or baking them with a drizzle of oil and a sprinkling of cheese. Often, garlic, anchovies, or herbs are added to the oil, and freshly grated Parmesan cheese is sprinkled on before serving or it is passed at the table.

Sometimes vegetables are used in combination, such as peas and artichokes, potatoes with bulbing fennel, and zucchini with peppers. Another common presentation is cooking a little prosciutto or pancetta and garlic in olive oil and adding cooked snap beans, zucchini, or fava beans.

In Italy vegetables are also grilled, braised, and baked. Grilling them over charcoal or gas has become popular in Italy in the past few decades. Some favorites are radicchio wedges, eggplant slices, zucchini, peppers, and tomatoes, grilled with a little olive oil and seasonings. They often accompany grilled meats and fish and sometimes are served with a flavored butter or a dipping sauce. Braising vegetables, often in a tomato sauce, has a long history in Italy. Zucchini and snap beans are favorite candidates for braising, as are endive, cabbage, and greens such as spinach and chard. Asparagus, artichokes, and cauliflower are enjoyed baked with a béchamel sauce or a drizzle of olive oil or butter and topped with grated cheese and/or bread crumbs.

Pasta

Pasta, a seemingly simple combination of wheat flour and water, is a beloved food in much of Italy. It is formed into many shapes—from bow ties, spirals, “ears,” rice shapes, and long strings to large, flat lasagna noodles—from either fresh dough or, much more commonly, dried. Today there are dozens of dried pastas available worldwide—most are of very high quality—and numerous types and varieties of fresh pasta are available from specialty food shops.

For many Italians, pasta is a daily staple. For the past few hundred years a pasta course has often started the meal. And the dressings for pasta seem endless. While meats, seafood, mushrooms, and cheeses are common, many vegetables are also featured with pasta—and not just the ubiquitous tomatoes. It’s not uncommon for the vegetables in the north of Italy to be prepared with butter, cream, or cheese. In the south vegetables are more often dressed with olive oil and seasonings. Generally the long thin noodles are served with light, slippery sauces that keep the noodles from sticking together; more substantial vegetable accompaniments are usually served with short pastas such as penne, rigatoni, orecchiette, or fusilli. These shorter noodles are also favored for baking.

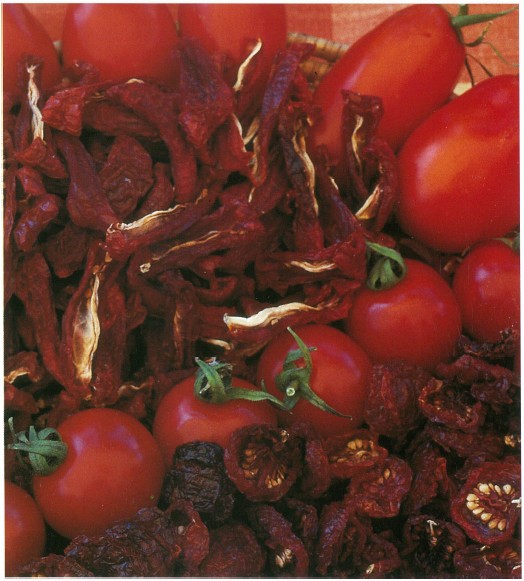

Both cherry and paste types tomatoes can be dried (left). Pasta is critical to Italian cuisine. Pictured here (above, clockwise from the top left) are farfalle, penne, gemelli, orecchiette, rigatoni, garlic pasta, fusili, conchiglie, and tricolor radiatore.

When you think of pasta and vegetables, it’s amazing to examine all the possibilities. There are spinach, arugula, and wild greens with olive oil and seasonings, tossed with penne pasta; rigatoni pasta with broccoli, olive oil, and garlic; asparagus, fava beans, and broccoli raab with orecchiette; fusilli with arugula and tomatoes; peas and ham with a cream sauce on fettuccine; and baby artichokes with pancetta. Then there is pasta with leeks and lemons, or radicchio and shrimp, squash blossoms and garlic, and Tuscan black kale and potatoes—they all grace Italian tables in different regions.

When preparing pasta, a useful rule of thumb is 2 ounces of dried or 4 ounces of fresh pasta per person for a traditional Italian pasta course, and nearly double that amount for a main dish. Cook the pasta in a very large pan, using 6 quarts of salted water for every pound of pasta. (If you are parboiling vegetables, in Italy it is common to first use the water to cook the vegetables and then the pasta.) Add the pasta to the already boiling water and cook until the pasta is al dente, or just barely tender, which may be from as little as 30 seconds for a fresh small pasta to 13 minutes or longer for large dry pastas. Stir the pasta occasionally. Drain the pasta only fleetingly so a small amount of cooking water still coats the noodles. Transfer the pasta to a warm bowl and immediately dress it with olive oil and seasoning, butter, cheese, or the sauce, tossing to prevent the noodles from sticking together. In Italy the usual proportion is 2 tablespoons of sauce to one portion of pasta. Americans usually like more sauce.

Although we usually think of pasta as a hot dish, there are many recipes for pasta salads. The pasta is dressed before it cools, and seasonings and vegetables are added. The dish is then refrigerated. As an aside, one of my favorite lunches is leftover cooked pasta. The following day I sauté it with a little olive oil to which I add chopped garlic, onions, and a few chopped fresh herbs such as chives, parsley, rosemary, basil, and oregano. When lightly brown I sprinkle the pasta with a little freshly grated romano cheese. Yum.

interview

Paul Bertolli

When I met Paul Bertolli, he was the chef at Chez Panisse restaurant in Berkeley, California. Today he has gone on to become the chef and owner of Oliveto Restaurant in Oakland, California, a restaurant that specializes in Italian food.

I went to Paul years ago for in-depth information on Italian cooking because I knew that Italian food had become his great interest. For five years Paul had cooked and traveled in Italy. During his stay in Italy, Paul worked with vegetables from the Florence produce market while cooking at restaurants in that city, and he also cooked with vegetables from an extensive garden at Villa la Pietra, a private residence where he was chef. I asked Paul to share his thoughts on Italian vegetables and their preparation and then talk about some of the individual vegetables.

The vegetable garden at Villa la Pietra was staffed by four gardeners. While there, Paul saw a few vegetables he’d never seen before, such as Tuscan black cabbage (a green to black or forest green member of the cabbage family that sends up large, slightly curled leaves from a thick central stem), artichokes with purple buds, and a number of greens and herbs that were gathered from the wild. But he was most impressed that the vegetables—even those that might be considered common—“were just really so good; great little string beans, red and white shelled beans, and the tomatoes all were outstanding.”

In Italy, “a common way to feature certain fresh vegetables, such as mushrooms, fennel, celery, and radishes, is to slice them very thinly,” Paul explained. Italians do this, for instance, when making a salad. Back in the United States Paul uses a refined method in which he shaves the vegetables with a mandoline. To protect your hand when using a mandoline, be sure to wear an oven mitt or use a mandoline guard.

One vegetable often sliced in Italy is the artichoke. “In Italy,” Paul said, “I saw artichokes with purple buds. They were wonderful eaten raw.” To prepare an artichoke for slicing, remove the tough outside leaves, cut off the top and most of the stem, pare the leaves remaining at the base, and slice it very thinly or shave it on a mandoline. Cut from the stem to the top of the artichoke. You’ll end up with a pile of shavings that look similar to planed wood. Because artichokes discolor very soon after they are cut, be prepared to serve them immediately. Just before serving them, drizzle on virgin olive oil, season with salt and pepper, and add a few drops of lemon juice; then make thin shavings of Parmesan cheese with a cheese slicer and scatter the cheese on top. For a variation, top slices of bresaola, very thinly sliced air-cured beef, with dressed artichokes cut in a similar manner.

One of Paul’s favorite vegetables is fennel. When it’s more fibrous, he likes to string it like celery. “Or, instead, you can just use the inner heart,” he said. “In this country, I feel fennel isn’t used enough. It has such a sweet flavor and goes well with so many other vegetables. It too can be served shaved, like the artichoke salad.”

Paul said he tried several different varieties of chicory when he lived in Treviso, near Venice. “I think the best I ever had were ‘Verona’ chicories that were very bitter because they had been left growing at the sides of the fields since the previous season and had not been blanched. Many Italians in the countryside eat the bitter chicories, but what you generally see commercially in the markets are the milder, blanched types of all those chicories. I don’t care for the market varieties; I prefer a strong, bitter flavor. As a chef, you’re always dealing with things that have these fine flavors. When I eat a strong chicory, I prefer to slice it very thinly. The dressing coats the sliced chicory more thoroughly, and this makes it seem less bitter. Sliced chicory is good combined with thinly sliced onions and drizzled with good red wine vinegar.” Paul also likes the Catalonian-type chicory, which Italians tie up and grill. After grilling it, they usually serve it topped with anchovies, onions, and olive oil.

Cime di rapa, or broccoli raab, Paul noted, is sometimes picked in Italy when it is tiny and leafy. Italians steam cime di rapa and use it as a nest for loin of pork, which is usually spit-roasted or braised.

In Italy arugula is used primarily in salads, but Paul sometimes likes to use it as a seasoning or herb. For instance, he uses it in ravioli: “I make pigeon ravioli and add a little arugula. I also use it on celeriac soup. It’s a wonderful garnish.”

gifts from the italian garden

This section includes recipes for Italian vegetables and herbs. Most are authentically Italian, but I must confess that, like most good cooks and gardeners, I can’t resist taking the principals and sometimes giving them my own stamp.

Basil in Parmesan

This recipe, from Rose Marie Nichols McGee, of Nichols Garden Nursery in Oregon, is a great way to preserve the taste of basil for the winter. It’s been so popular, she’s had it in her herb catalog since 1982. As she says, “I never tire of fresh tomatoes sprinkled with this blend. Use it on salads, pasta, and fresh or cooked tomato dishes. This recipe makes a good basis for a later preparation of pesto. Small jars frozen and presented as gifts later in the year will be much appreciated.” It stays fresh in the refrigerator for one week. Freeze it for longer storage.

1 bunch fresh green basil

Approximately ¾ cup Parmesan cheese, freshly grated

Rinse the basil and dry it in a salad spinner. Roll a handful of basil leaves into a bunch and with a sharp knife cut the leaves into a thin chiffonade. Repeat the process with the rest of the basil. You should have about 1¼ cups chopped. In a half-pint canning jar with a tight-fitting lid, layer ¼ inch of Parmesan cheese on the bottom, then layer ¼ inch of basil, then layer another ¼ inch of Parmesan, and so on. Press down firmly on the top to remove any air pockets, and then sprinkle on a final layer of Parmesan.

Makes about 2 cups.

Nepitella Butter

Try this butter melted over steamed artichokes and carrots and in all sorts of fish or poultry dishes. In Italy nepitella is often paired with eggplant and mushrooms. The butter may be frozen for up to three months.

Caution: There is some evidence that large amounts of nepitella-related plants can cause miscarriage, so pregnant women should avoid it.

1 small handful of nepitella

4 ounces sweet butter (1 stick), room temperature

1 teaspoon finely grated lemon zest

Wash the nepitella leaves well—examine them for critters. Gently pat dry the leaves in a towel. With a very sharp knife mince the leaves. (Mincing is easier if you gather the leaves into a small ball before cutting them.) You need about 2 tablespoons of finely chopped leaves.

Cut the stick of butter into 6 or 8 pieces and then with a fork slowly work the butter into the nepitella and lemon zest, mashing to incorporate them. Use a rubber spatula to put the mixture into a small butter crock or decorative bowl. Refrigerate until serving time.

Makes ½ cup.

Roasted Pimientos

Use these peppers to add zing to your sandwiches, soups, pasta dishes, and sauces.

An herb butter (right) is a versatile flavoring device. For Italian dishes, herb butters made with nepitella, basil, parsley, and oregano are appropriate.

Approximately 12 large pimiento peppers

8 garlic cloves

¾ to 1 cup extra-virgin olive oil

Roast the peppers under the broiler or on the grill, peel them, and remove the seeds and stem ends. Layer the peppers in a quart jar with a good seal.

Lightly crush the garlic cloves with the back of a chefs knife. In a small frying pan, heat the oil and slowly sauté the garlic over low heat for about 5 minutes. Do not brown the garlic. Remove the garlic and slowly pour the oil over the peppers. Occasionally run a rubber spatula carefully around the sides of the jar to allow the oil to fill all the air pockets. Refrigerate.

Half an hour before using, take the peppers out of the oil and drain them. Let them come to room temperature and serve them as part of an antipasto or use them in other recipes.

Makes 1 quart.

Dried Tomatoes

Dried tomatoes have an intense flavor and can be used in a multitude of recipes, from vinaigrettes to sauces and soups. They keep for months in a cool, dark, dry place or when frozen. If you have a problem with meal moths, store the tomatoes in the freezer. To soften and rehydrate them for use in sandwiches and sauces, pour boiling water or stock over them and let them sit for a few minutes, or until the skins are soft. The liquid from the rehydrated tomatoes is great for adding flavor to dishes.

Wash the tomatoes and drain them dry. Cut the tomatoes in half (cut 2- to 3-inch paste tomatoes into three or four slices) and place them skin-side down on the dehydrator tray. Put the tray in the food dehydrator and follow the directions for drying tomatoes. Different models have different heat-and time-setting recommendations.

If you have a gas oven with a pilot light, you can put the tomatoes on racks and dry them using only the heat from the pilot light (keep the door closed). It takes about 3 days to dry tomatoes this way.

Tomatoes can also be dried in the sun in hot, arid climates. Lay the tomatoes out on a clean window screen that is plastic-coated (or otherwise not made of metal). Place the screen in a very sunny location and cover it with another screen to keep off the flies. Bring the tomatoes in at night to get them out of the dew. Depending on the weather, they will dry in 3 to 7 days. Dry them until they are leathery and not sticky.

Transfer thoroughly dried tomatoes into zippered, freezer-strength plastic bags. Store them in a cool, dry, dark closet.

Pickled Capers

Pickling is one of a number of ways to preserve capers. Pickled capers can be used on pizza, in sauces, on sliced tomatoes, and with smoked salmon. Let the caper buds sit in a dark place for a few hours before pickling.

1 quart fresh caper buds

1½ cups white wine vinegar

1 teaspoon mustard seeds

1 teaspoon dill seeds

⅓ cup packed brown sugar

1 teaspoon salt

1 teaspoon celery seeds

1 garlic clove, crushed

Wash the capers and distribute them among sterilized canning jars. In a saucepan (avoid aluminum, which discolors the buds), combine the remaining ingredients with ½ cup water, bring to a rolling boil, and boil rapidly for 10 minutes. Strain the vinegar mixture and bring it to a boil again. Remove from the heat immediately. Pour the boiling mixture over the capers. Seal the jars tightly and store them for at least two weeks before using.

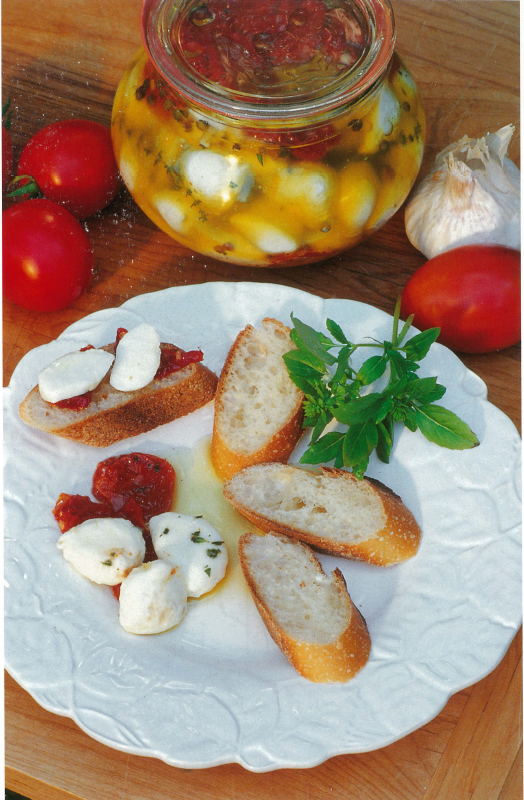

Mozzarella Marinated with Garlic, Dried Tomatoes, and Basil

Arrive at the party with this lovely treat or serve it as an appetizer with focaccia or as part of an antipasto. Once the cheese and tomatoes have marinated, use the richly flavored olive oil for dressings or serve it with rustic bread for dipping. These mozzarella balls will keep in the refrigerator for about a week.

1 cup dried tomatoes (see page 67)

¾ pound fresh 1-inch mozzarella balls

8 garlic cloves, minced, divided

1 teaspoon chopped fresh thyme, divided

1 teaspoon chopped fresh marjoram, divided

1 teaspoon whole green peppercorns or capers, divided

½ teaspoon salt, divided

¼ teaspoon freshly ground black pepper, divided

Approximately 1¼ cups extra-virgin olive oil

In a small bowl, pour 1 cup of boiling water over the dried tomatoes and let them sit for at least 15 minutes, or until they’re soft. Drain them and set them aside.

Remove the mozzarella balls from the brine and drain them.

In a quart jar with a lid, layer half the tomatoes on the bottom, then make a layer using half the garlic, herbs, and seasonings. Layer all the mozzarella balls next. Make a top layer of the remaining tomatoes, then the remaining garlic, herbs, and seasonings. Pour the olive oil over the final layer, making sure to cover all the ingredients. Refrigerate to marinate for at least 24 hours.

Makes 1-quart.

Bruschetta with Tomatoes and Basil

This rustic appetizer has crunch, complexity, and few calories, and it showcases a classic pairing: basil and tomatoes.

For the bruschetta:

8 thick slices crusty Italian bread

4 garlic cloves (2 peeled, 2 pressed), divided

For the topping:

3 tablespoons fruity extra-virgin olive oil, divided

16 to 20 medium fully ripe plum tomatoes

2 to 3 tablespoons finely chopped, fresh ‘Sweet’ or ‘Spicy Globe’ basil

Salt and freshly ground black pepper

Garnish: sprigs of fresh basil

To make the bruschetta: Toast the bread to a medium brown. While it’s still warm, lightly rub one side of each piece with the peeled garlic, using about a quarter clove per piece. Drizzle 2 tablespoons of the olive oil over the toasted bread, dividing it equally among the slices. Set the toast aside, garlic-side up, on a medium-size platter until ready to serve.

To make the topping: Fill a medium-size saucepan half full of water and bring it to a boil. Immerse the tomatoes for 30 seconds, drain and rinse them with cold water, and then peel them. Remove the seeds and chop the tomatoes into half-inch dice. In a small bowl, combine the tomatoes with the pressed garlic, the remaining tablespoon of olive oil, the basil, salt, and pepper. Adjust the seasonings. Set the bowl aside and let the flavors meld for 30 minutes. Before serving, drain the tomato mixture in a sieve for a few minutes.

To serve, spoon a few generous tablespoons of tomatoes on each piece of toast on the garlic-flavored side. Garnish the plate with the fresh basil leaves.

Serve immediately.

Classic Minestrone Soup

This minestrone is in the Ligurian style, finished with a flavor burst of rosemary pesto.

3 tablespoons extra-virgin olive oil

1 large yellow onion, sliced

2 (⅓-inch-thick) slices prosciutto, (about ⅓ to ½ pound), julienned

2 large carrots, sliced

8 chard leaves or black kale, washed and cut into thin strips

1 small green cabbage, sliced thin

14 to 16 ripe Italian paste tomatoes, peeled, seeded, and chopped, or 3 tablespoons sun-dried tomato paste

8 cups chicken or vegetable stock

3 large garlic cloves, minced

Handful of fresh Italian parsley leaves

Leaves from 2 (3-inch) sprigs of fresh rosemary

6 tablespoons freshly grated Parmesan cheese plus extra for garnish

½ dried hot pepper

2 cups cooked cannellini beans, or 1 (15¼-ounce) can kidney beans

2 handfuls of romano beans, cut into 1-inch pieces

1 small green zucchini, sliced

4 ounces wide pasta noodles, broken into 3-inch pieces

Salt and freshly ground black pepper

In a large stockpot, heat the oil and sauté the onion and prosciutto over low heat until the onions are translucent, about 7 minutes. Add the carrots, chard, cabbage, and tomatoes. Cook together for a few minutes, then add the stock. Cover the stockpot and simmer for about 1¼ hours. The soup can be cooled and then refrigerated (or frozen) at this point.

In the meantime, in a mortar pound the garlic, parsley, rosemary, Parmesan cheese, and hot pepper to a crumbly paste and set it aside.

Half an hour or so before serving, bring the soup to a simmer; add the cannellini and romano beans, zucchini, and pasta; and cook for 5 to 10 minutes, or until the beans and pasta are tender. Stir in the rosemary mixture, season with salt and pepper, and serve in individual bowls topped with Parmesan cheese, or let diners sprinkle the rosemary pesto over their own bowl.

Serves 6.

Misticanza

Generally, misticanza is to Italy what mesclun is to France—namely, a mix of mostly young salad greens served with a vinaigrette. Historically, misticanza is more piquant and bitter than most mesclun. Misticanza evolved from the practice of gathering wild greens and mixing them in a salad. Today it is a term for a salad of young leaf lettuces, greens, and herbs, either wild or cultivated.

When you have a garden, what goes into your salads depends on what you choose to grow and what is ready to harvest in your garden at any given time.

For the salad:

6 large handfuls of mixed greens such as spinach, arugula, corn salad, chicories, sorrel, lettuces, and frisées

A few leaves of Italian parsley, fennel, chervil, mint, or basil

For the vinaigrette:

2 to 2½ tablespoons red wine vinegar

1 garlic clove, minced

Salt and freshly ground black pepper

5 to 6 tablespoons extra-virgin olive oil

To make the salad: Wash the greens and herbs and dry them in a salad spinner. Refrigerate until serving time.

To make the vinaigrette: In a small bowl, mix the vinegar, garlic, salt, and pepper and blend in the oil to taste. Just before serving, toss the dressing gently with the salad and serve.

Serves 6.

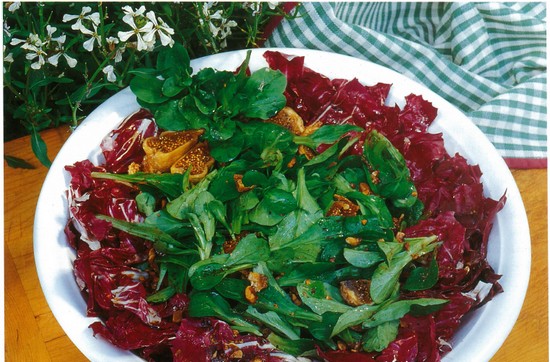

Radicchio and Corn Salad with Figs and Hazelnuts

This salad is rich and filling, with a nice balance of bitter and sweet. For a party presentation, line the bowl with the radicchio, layer the corn salad on top, and sprinkle on nuts and figs. Dress the salad at the table and toss.

For the salad:

1 small head radicchio

3 cups corn salad (mâche)

5 dried figs, divided

¼ cup (2 ounces) hazelnuts

1 tablespoon baking soda

For the dressing::

¼ cup hazelnut or extra-virgin olive oil

3 tablespoons balsamic vinegar

Salt and freshly ground black pepper

To make the salad: Tear the radicchio into bite-size pieces. In a large salad bowl, mix it with the corn salad. Coarsely chop two of the figs and add them to the salad; halve the remaining three figs and set them aside.

To peel the hazelnuts, bring 2 cups of water to a boil in a large saucepan. Add the baking soda. Boil the hazelnuts for 5 minutes. Heat the oven to 350°F. Drain and rinse the nuts, and rub off the skins with your fingers. Place the hazelnuts on a cookie sheet and roast them for 10 minutes, or until they’re a light brown. Cool the hazel nuts, chop them coarsely, and add them to the salad.

To make the dressing: In a small bowl, whisk together the oil, vinegar, salt, and pepper. Pour the dressing over the salad and toss lightly. Garnish with the fig halves and serve.

Serves 4 to 6.

Classic Broccoli Raab

This variation on a traditional Italian recipe was developed by Joe Queirolo, garden manager of Mudd’s Restaurant, in San Ramon, California, and onetime garden manager of my garden. Joe serves the broccoli over orecchiette or polenta.

1 bunch broccoli raab

2 tablespoons extra-virgin olive oil

1 or 2 garlic cloves, minced

¼ cup white wine

¼ cup grated Pecorino-Romano cheese

Salt and freshly ground pepper

Wash the broccoli raab and trim off or peel any coarse stems. Bring a big pot of salted water to a boil. Add the broccoli raab and boil for about 3 to 5 minutes, or until tender. Drain the broccoli raab and run it under cold water so that it will hold its color.

Meanwhile, heat the oil and sauté the garlic over medium heat until softened, about 1 minute. Add the broccoli raab and toss. Stir in the white wine and let the mixture reduce for 2 or 3 minutes, shaking the pan occasionally. Add salt and pepper to taste. Pour into a serving dish and sprinkle on the cheese; serve immediately.

Serves 4 as a side dish.

Beans, Italian-Style

Preparing beans in the Italian manner means cooking them twice. Bring a large pot of water to a boil, add the beans—be they green or yellow snap beans, romano beans, shelled horticultural beans, or fresh favas—to the water and cook them until they are just tender but still have a hint of crunch. Drain them and then reheat them with flavorings before serving. Butter is sometimes used in this last stage, but a more common finish for the beans is to reheat them in olive oil and garlic and then sprinkle them with Parmigiano-Reggiano cheese. Sometimes mashed anchovies are added to the olive oil.

Following are two variations on Italian beans.

1 pound shelled fresh fava beans (2 to 2½ pounds of large fava bean pods)

1½ tablespoons of extra-virgin olive oil

2 garlic cloves, minced

Salt and freshly ground black pepper

Freshly grated Parmigiano-Reggiano cheese

In a large saucepan, bring 6 to 8 cups of water to a boil. Add the shelled fava beans and cook them until tender, about 8 to 12 minutes depending on their size. Pour the beans into a colander and let them cool for a few minutes. If the beans are fairly mature, the outside skin must be removed at this time. Very young beans, ½ inch or so in diameter, need no peeling.

In a small frying pan, heat the oil and sauté the garlic for a few minutes, but do not let it brown. Add the peeled favas and bring them to serving temperature. Lightly salt and pepper the beans. Adjust seasonings, transfer them to a warm bowl, and sprinkle on cheese.

Serves 4.

1 pound green or yellow ‘Romano’ or snap beans

1½ tablespoons olive oil

2 garlic cloves, minced

Salt and freshly ground black pepper

Freshly grated Parmigiano-Reggiano cheese

Wash and string the beans if necessary. Remove the stem ends. If the beans are large, cut them into 2-inch lengths. Precook the beans as described above. They will cook from 4 to 7 minutes, depending on their size and age. (‘Romano’ beans cook more quickly than standard snap beans.) Cook until they are just tender. Drain the beans and proceed as described above.

Serves 4.

Grilled Eggplant with Nepitella

Nepitella is a favorite seasoning in some parts of Italy, tasting somewhat like a combination of a mild mint and a little oregano. Use the butter sauce with poultry and with all types of grilled mushrooms as well as with eggplant.

1 to 3 tablespoons extra-virgin olive oil

1 medium eggplant, cut into

½-inch slices

2 tablespoons butter

1 teaspoon nepitella, minced

With your fingers rub a little olive oil on both sides of each slice of eggplant. You may need more oil, but try not to get the eggplant slices saturated. Grill the eggplant over a medium to hot fire for about 4 minutes on each side, or until slightly brown but not mushy. Meanwhile, melt the butter in a small frying pan and add the nepitella. Transfer the eggplant to a serving dish and drizzle on the nepitella butter.

Serves 4 as a side dish.

Tarragon and Balsamic Vinegar-Braised Onions

All sorts of onions are popular in Italy, especially when baked. The addition of balsamic vinegar and tarragon is a bonus. Roasted with just a little olive oil, onions are low in fat and calories and are the perfect appetizer or side dish for a holiday roast.

6 medium red onions, peeled

4 tablespoons extra-virgin olive oil

5 tablespoons balsamic vinegar

1 tablespoon fresh chopped tarragon

Dash of salt

Freshly ground black pepper

Preheat the oven to 350°F. Place the onions in a baking dish, sprinkle them with olive oil, vinegar, tarragon, salt, and pepper. Bake for about 1½ to 2 hours, or until they’re tender and lightly browned. Baste them often with the liquid as they bake.

Serves 6.

Grilled Radicchio and Zucchini with Agliata

This a surprisingly delicious way to enjoy vegetables. Radicchio and zucchini have a luscious smoky flavor and sweetness when they’re grilled. Serve the vegetables with grilled chicken, steak, or fish. For a vegetarian feast, serve it with polenta and grilled portobello mushrooms.

4 small zucchini

1 large radicchio

For the sauce

1 garlic head and 3 minced cloves, divided

¾ cup and 3 tablespoons extra-virgin olive oil, divided

¼ cup balsamic vinegar

2 cups day-old Italian rustic bread, crust removed, cubed

2 tablespoons fresh Italian parsley, chopped

¼ teaspoon salt plus extra

Freshly ground black pepper

To make the sauce: Preheat the oven to 350°F.

With a sharp knife cut off the top of the garlic head until the cloves are exposed. Place the garlic in a small baking dish and sprinkle on 1 tablespoon of the olive oil. Bake the garlic for 20 minutes, or until it’s soft. Set it aside.

In a bowl mix the balsamic vinegar and ¼ cup of water. Add the bread cubes and soak them for about 15 minutes or until they’re very soft. Squeeze the liquid out of the bread and put the bread into a mixing bowl. Squeeze the roasted garlic from its paper onto the bread. Add one of the minced garlic cloves, and the parsley. Blend all the ingredients into a thick paste. Season with the salt and pepper. Stir in ¾ cup of olive oil, a few drops at a time, to make an emulsion. The oil will not be absorbed completely; a little oil on top is traditional.

To cook the vegetables: Cut the zucchini lengthwise and quarter the radicchio. Place them in a shallow baking dish. Blend the remaining two minced garlic cloves with the remaining 2 tablespoons of olive oil and brush the zucchini and radicchio with the mixture. Season with salt and pepper. Let the vegetables marinate for at least 1 hour.

Grill the radicchio over a medium flame, turning it often so each side blackens slightly and the vegetables are tender inside, about 10 to 12 minutes. At the same time grill the zucchini halves on both sides until they’re golden and tender, about 10 to 12 minutes. Transfer them to a warm serving plate. (Instead of grilling them, you may broil the radicchio and zucchini in the oven. Broil at 400°F for 6 to 10 minutes, or until golden.)

Serve immediately and pass the agliata sauce for diners to serve themselves.

Serves 4.

Nests with Wild Greens and Fontina

This is a delicious and attractive way to serve an assortment of wild greens. It makes a lovely side dish served with egg dishes or fish, or spooned on crostini to make a beautiful and unusual appetizer. A traditional variation substitutes poached eggs in each nest instead of cheese.

2 pounds wild mixed greens, such as arugula, young borage leaves, dandelion greens, spinach, black cabbage, chicory, endive, violet leaves

2 tablespoons extra-virgin olive oil

2 garlic cloves, minced

1 pinch ground red pepper

Salt and freshly ground black pepper

½ cup Fontina Val d‘Aosta cheese, grated

Preheat the oven to 350°F. Remove the stems from the greens and wash them thoroughly. Steam them for 3 to 4 minutes, or until they have wilted. Drain the leaves and rinse them under cold water. Drain them again in a colander, squeezing out the excess water. In a frying pan, heat the olive oil and sauté the garlic over low heat for about 2 minutes. Add the greens, hot red pepper, salt, and black pepper and sauté for 2 more minutes. Let the greens cool to room temperature. Divide them into six equal portions and shape each portion into a ball. Place the balls in a baking dish and with your thumb make an indentation in the center of the ball to form a little nest. Fill the indentation with the grated Fontina cheese. Bake the nests for 5 minutes, or until the cheese has melted.

Serves 6.

Fettuccine with Fresh Marinara Sauce

This recipe calls for fettuccine, but any long noodle would work. The sauce is also great on polenta and grilled vegetables. Vary the herbs at whim—try any combination of parsley, tarragon, thyme, fennel, and anise seeds.

1 pound dry fettuccine noodles

¼ pound Parmigiano-Reggiano cheese (not grated)

For the sauce

2 tablespoons extra-virgin olive oil

1 large onion, minced

3 garlic cloves, minced

1 medium Italian bell pepper, roasted, peeled, and chopped

Approximately 20 paste tomatoes, blanched, peeled, seeded, and chopped (about 4 cups)

1 teaspoon chopped fresh Greek oregano

½ cup chopped fresh basil

Salt and freshly ground black pepper

To make the sauce: In a pan, heat the oil and sauté the onion until transparent, about 7 minutes. Add the garlic and sauté for 3 more minutes.

Add the bell pepper, tomatoes, oregano, and basil, lower the heat, and simmer for about 25 minutes, or until the mixture is fairly thick. Salt and pepper to taste.

Makes approximately 3½ cups.

To make the noodles: Boil 6 quarts of salted water. Add the fettuccine noodles and stir them for a few seconds to keep them separated. Boil the fettuccine until just barely tender, usually about 11 minutes. Drain the noodles in a colander and immediately pour them into a warm serving bowl. Pour on the warm sauce, toss, and serve immediately. Pass the cheese with a grater so diners can serve themselves.

Serves 6 to 8 for an Italian pasta course, or 4 to 6 as an American-style entrée.

Penne with Arugula

This is a pasta dish with complexity and a full flavor. It can be served as a pasta course or a light supper.

2 tablespoons extra-virgin olive oil

2 portobello mushrooms, sliced (about 2 cups)

3 garlic cloves, minced

6 thin slices (¼ to ⅓ pound total) prosciutto, chopped

4 paste tomatoes, peeled, seeded, and chopped (about 2 cups)

4 cups young arugula leaves Freshly ground black pepper

4 cups dried penne

4 tablespoons Asiago cheese, grated

In a deep frying pan, heat the olive oil and sauté the mushrooms over medium heat for 3 to 5 minutes, or until the mushrooms are lightly browned. Add the garlic and prosciutto and sauté for 2 more minutes. Reduce heat, add the tomatoes, and simmer for 1 more minute. Add the arugula and toss it in the pan until it has wilted, about 1 minute, then season with pepper.

Meanwhile, bring 3 quarts of salted water to a boil, add the penne, and cook until it’s al dente, about 6 to 9 minutes. Drain the penne. In a warm bowl, toss the penne with the vegetables, and serve with grated Asiago cheese.

Serves 4 as a side dish.

Risotto-Stuffed Swiss Chard

Large chard leaves are great for stuffing. Serve stuffed chard as a course by itself or as a side dish with meat, fish, and poultry.

2 tablespoons butter

½ medium onion, chopped

4 ounces prosciutto, chopped

1 portobello mushroom, or 6 button mushrooms, chopped

1 cup arborio rice

½ cup dry white wine

3 to 4 cups low-salt beef broth

¼ cup Parmesan cheese, grated

12 Swiss chard leaves

½ cup tomato sauce

½ cup Gruyere cheese

In a heavy saucepan, melt the butter and sauté the onion, prosciutto, and mushrooms over medium heat until tender, about 10 minutes. Add the rice and stir to coat the rice evenly. Add the white wine and simmer, stirring, until the liquid has evaporated. Add the broth, 1 cup at a time, always stirring. Simmer for 20 to 30 minutes; rice should be al dente. Stir in the Parmesan cheese.

Preheat the oven to 350°F. Remove the thick lower part of the chard stalks. Steam the leaves for 2 minutes, or until they have wilted. Drain the leaves and rinse them under cold water. Drain them again and place the leaves on paper towels to absorb the moisture. Spoon approximately 2 tablespoons of the arborio mixture onto the middle of each leaf, putting less in smaller leaves. Fold the sides toward the center, then fold in the ends. Make sure the ends overlap to keep the filling secure. Place each package seam-side down in a shallow baking dish that has been brushed with a little olive oil. Spoon tomato sauce over each package. Sprinkle the stuffed chard leaves with the Gruyere and bake them for 20 minutes. Serve immediately.

Serves 4, three per person.

Savory Bread Pudding with Sorrel and Baby Artichokes

This unusual and complex dish combines the nutty flavors of Swiss cheese and artichokes with the lightness of sorrel, interwoven with layers of fresh herbs. It can serve as the star of the meal served with an endive or beet salad and a good red wine, or accompany filets of salmon or tuna.

1 loaf of rustic Italian bread, or about 12 slices of leftover substantial breads of all types (avoid soft sandwich-type breads, since they tend to produce a gummy dish)

1 tablespoon fresh lemon juice

1 pound 2-inch-long baby artichokes (approximately 18)

3 cups nonfat or low-fat milk

5 eggs, beaten

1 teaspoon salt

1 teaspoon pepper

¼ cup grated Parmesan cheese, divided

4 ounces Monterey Jack cheese, slivered, divided

4 ounces Emmentaler cheese, slivered, divided

2 tablespoons snipped fresh chives

2 tablespoons chopped fresh Italian parsley

2 tablespoons chopped fresh lemon thyme

1½ cups chopped sorrel leaves

1 tablespoon butter, cut into small pieces

If you’re using fresh bread, cut the loaf into 12 equal slices and arrange the slices on two cookie sheets. Bake at 200°F for about 30 minutes, or until dry but not brown. Let the bread cool.

While the bread is in the oven, prepare the artichokes. Partially fill a small bowl with water and add the lemon juice. Peel off any dried or bruised leaves from the artichokes, cut off the top ⅓ inch and discard it, and immediately immerse the artichokes in the lemon water to prevent them from turning brown. Place 1 inch of water in the bottom of a steamer and bring it to a boil. Drain the artichokes and put them in the steamer basket, cover, and steam them over medium heat for about 20 minutes, or until they’re just tender. Remove them from the heat and set them aside.

Break up the toasted bread slices and put them in a shallow baking dish. Pour the milk over the bread and let it soak for about 20 minutes, stirring the bread around to make sure it absorbs the milk and gets soft. After it has soaked, squeeze the milk out of the bread and set it aside. Pour the leftover milk into a measuring cup, adding more to get to ½ cup if necessary. In a bowl combine the ½ cup milk, eggs, salt, and pepper and mix well. Set aside.

Preheat the oven to 350°F. Oil a 3-quart casserole. Layer one third of the bread in the bottom of the casserole. Layer two thirds of the artichokes over the bread, then layer half of the three cheeses combined and then half the sorrel and herbs. Layer another one third of the bread, add the final one third of the artichokes, (reserve a few for the top), the last half of the sorrel and herbs, and the rest of the cheeses, reserving 3 tablespoons for the top. Top the casserole with the last one third of the bread and the reserved artichokes. Pour the milk and egg mixture over the bread, sprinkle on the reserved 3 tablespoons of combined cheeses, and dot with butter.

Bake for about 45 minutes, or until the top is nicely browned and a knife inserted halfway into the middle comes out clean. Serve hot.

Serves 4 as a hearty supper, 6 as a side dish.

Spring Pizza

Pizza can be made with dozens of different vegetables. This particular pizza includes the traditional spring goodies—arugula and artichokes. I prefer a lesser amount of cheese, 6 ounces, for a lean pizza; other folks prefer their pizza “cheesy” and should use 8 ounces of cheese.

4 baby artichokes

8 dried tomatoes

2 tablespoons extra-virgin olive oil

3 garlic cloves, minced

1 (12-inch) prebaked commercial pizza shell

6 to 8 ounces of fresh mozzarella cheese, sliced thin

10 black, dried, piquées or kalamata olives, pits removed

1 teaspoon fresh oregano, minced

1 cup young arugula leaves

¾ cup Asiago cheese, grated

Preheat the oven to 500°F. Cut the top ½ inch off the baby artichokes. Cover them with water and simmer them for 10 minutes, or until tender. Cool the artichokes.

While the artichokes are cooking, chop the tomatoes coarsely and reconstitute them in warm water for 10 minutes.

Blend the olive oil with the garlic. Spread the oil mixture evenly over the pizza shell. Distribute mozzarella cheese slices evenly over the pizza shell. Quarter the cooked artichokes and put them on top of the mozzarella. Add the olives and tomatoes and sprinkle them with the oregano. Bake the pizza for 7 to 10 minutes, or until the cheese has melted. Remove it from the oven, cover it evenly with arugula, and sprinkle on the Asiago cheese.

Either serve the pizza as is or return it to the oven for 2 more minutes to wilt the arugula and melt the Asiago.

Makes 1 medium-size pizza that serves 2.

Don Silvio’s Vegetable Dessert Tart

Vicki Sebastiani, from Viansa Winery, contributed this recipe for a surprisingly rich and delicious dessert made with vegetables.

For the tart shell:

2 cups all-purpose unbleached flour

½ cup walnuts, chopped fine

1 cup butter (2 sticks), chilled

For the filling:

2 cups coarsely chopped raw chard leaves (about 1 bunch)

2 cups grated zucchini (about 2 medium zucchini)

1 cup golden raisins

8 leaves chopped fresh mint, or 1 teaspoon dried mint

¼ cup honey

4 eggs, lightly beaten

½ cup Viansa Frescolina Chardonnay or Savignon Blanc wine

To make the shell: In a bowl, combine the flour and nuts. Add the butter, 2 tablespoons at a time, and mix well in food processor until the dough forms a ball. With your fingers spread the dough into a quiche, tart, or pie pan (9 to 10 inches in diameter) to ⅛-inch thickness along the bottom and sides and at least ¾ inch up the sides. Chill the shell while you make the filling.

To make the filling: Preheat the oven to 375°F.

In a large bowl, combine all the filling ingredients. Pour half the filling into a food processor or blender and puree briefly. Combine this portion of the filling with the nonpureed portion of the filling and pour into the shell. Bake the tart for approximately 45 minutes, or until the filling has set (until an inserted knife comes out clean). Cool for 30 minutes before serving. Serve at room temperature.

Serves 6 to 8.