My doctor gave me six months to live. But when I couldn’t pay the bill, he gave me six months more.

Walter Matthau, comedian

It’s not all bad news. Despite the preceding chapter and its gloomy picture of medical science, there is a silver lining. As many doctors are ready to admit, medicine is an uncertain science. By accepting and understanding these uncertainties and the illusion of control that surrounds them, you can make better decisions about your health. Here, then, is the positive side of the story.

During the Second World War, Dr Henry Beecher, an American doctor operating in Anzio, Italy, ran out of morphine. He started injecting his patients – some of whom had terrible injuries – with a harmless saline solution. To his surprise, there was little difference in the results. The soldiers thought they’d received morphine, and the salted water, acting as a placebo, seemed capable of suppressing quite excruciating pain even among those recovering from amputations. But of course, it wasn’t really the saline solution doing this. It was the human mind.

Stories of the incredible power of the mind to cure the body are not simply found in the literature of pain-killing and drugs. In the late 1990s, for instance, a Swedish hospital operated on eighty-one people who had a condition in which the heart muscles thicken abnormally. Typically, some sufferers experience only mild effects, while others become seriously ill and die. A common cure is to insert a pacemaker, which is exactly what happened to the eighty-one patients. The twist was that for half of them, the pacemakers weren’t turned on! And yet they all experienced the same kind of improvements (though to a slightly lesser extent in the case of those whose pacemakers were switched off): less chest pain, dizziness, shortness of breath, and heart palpitation.1

Readers of the previous chapter may be suspicious of the small sample size in this example. So here’s another case from the placebo literature. In a large group of men, aged thirty to sixty-four, who had suffered a heart attack during the previous three months, 1,103 were given a potent drug (clofibrate) and 2,789 a placebo. The researchers followed their progress for at least five years and found almost no difference in mortality rates between the two groups: 20% of those on the real drug and 20.9% of those taking the placebo died. The scientists also noticed that those who took their pills regularly had better survival rates. Of patients on the active drug who took more than 80% of the prescribed dose only 15.7% had died five years later (compared to 22.5% of those who took less than 80%). However, the same thing happened in the placebo group. Of those who took more than 80% of the fake medicine, only 16.4% had died five years later (compared to 25.8% of those who took less than 80%).2

The conclusion is that placebos can work almost as well as real medicine. A.K. Shapiro, one of the most noted authorities in this field, summarizes the situation as follows.

Placebos can be more powerful than, and reverse the action of potent, active drugs. The incidence of placebo reactions approaches 100% in some studies. Placebos can have profound effects on organic illness, including incurable malignancies. Placebos can often mimic the effects of active drugs.3

For those of us in search of positive messages, the lesson here is that the human mind can produce effects as strong as the most powerful drugs. Despite over fifty years of research, science is yet to explain fully the self-healing or pain-suppressing power of the placebo, but the implications for our health and longevity are significant. How much more can the mind and body achieve together?

Perhaps some of the answers to the placebo mystery will be uncovered by the more recent medical interest in “self-rated health.” The rise of the internet has brought with it all kinds of life-expectancy calculators and do-it-yourself health-assessment tools. It’s not yet clear how accurate these are, but several studies have compared the ability of doctors to assess our health and life-expectancy with our own ability to do the same. In such research, doctors typically read the medical history, see the results of tests, and carry out a detailed examination for each person concerned. Independently of the doctor’s prediction, the person is then asked to answer a simple, multiple-choice question such as the following:

In general, would you say your health is:

(a) Excellent (b) Very good (c) Good (d) Fair (e) Poor?

(please circle the right answer)

Surprise, surprise . . . self-rated health scores provide more accurate indications of how much longer people will live than the doctors’ predictions – at least according to the research in this area.4 Those rating their health as “excellent” – especially the women – were between two and ten times as likely to be alive six to ten years later than people who rated their health as poor. Even current age and smoking, the two best objective indicators, were less reliable predictors of longevity than the simple multiple-choice question. People, it turns out, and particularly older ones, are the best judges of how long they will live, based on a simple assessment of how they feel right now.

So that’s our positive lesson number one. If you feel good, you’re probably doing something right. Unless you’re a hopeless hypochondriac, you should probably trust the signals your own body is giving you – and the power of your own mind to influence your body. We’re not saying that your body and mind, working together, guarantee the certainty that medical science lacks, but that they provide a fairly reliable indicator of whether to consult a doctor.

Ah, but . . . what if your body and mind are plotting to hide something from you? Shouldn’t you have an annual check-up or regular tests for killer diseases? As we mentioned in the introductory chapter, this sounds like common sense, but empirical evidence reveals no difference in life expectancy between those who undergo annual checkups and those who don’t. And there sure is plenty of empirical evidence. Doctors have been recommending yearly health checks since 1920, but recent studies reveal that millions of annual checkups over the years have neither improved patients’ health nor prolonged their lives.5

Of course, screening programs vary across countries, cultures, and time. Attitudes to preventive testing often depend on how healthcare is funded. The vested interests of private healthcare providers and insurance companies in the US, for instance, are very different from the cost-saving instincts of the state-run National Health Service in the UK. It’s important to understand not only the economic context but also the evidence for the test in question. To explain what we mean, let’s take two examples: one for the benefit of younger women, the other especially for older men.

The first example is highlighted by a change in the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ recommendations to pregnant women, proclaimed at the beginning of 2007. Previously, the advised form of screening for Down’s syndrome was a blood test. The more expensive amniocentesis test, which takes a sample of the fluid in the womb, had been recommended only for women over thirty-five, who are at greater risk, or those for whom the blood test had indicated abnormalities. The new advice was that all pregnant women, regardless of age or blood-test results, should have the more expensive test.6

Now, doctors rarely mention this, but all tests are subject to two types of errors. In this case, one possible – but very rare – error is that the test fails to detect a baby with Down’s syndrome. This is called a false negative. The other possible – and much more common – mistake is that the test indicates Down’s syndrome for a completely normal fetus (often leading to an unnecessary termination). This is called a false positive. A third problem, specific to amniocentesis, is that it occasionally causes a miscarriage. All three problems can lead to a great deal of heartache in their different ways.

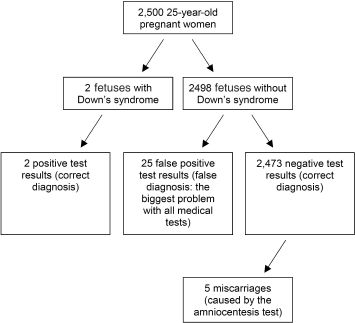

Putting heartache aside, let’s look dispassionately at the statistical evidence. Figure 1 indicates the various outcomes for a theoretical population of 2,500 pregnant twenty-five-year-old women. Given that the rate of Down’s syndrome is about 1 in 1,250, two of the women will have fetuses with the abnormality, whereas 2,498 won’t – that’s the second level down. The third level gives the outcome of amniocentesis for the two groups of women. As the chances of a false negative are very small, we’ll imagine that both the Down’s syndrome babies are identified. The chances of a false positive are also small: about 1% in fact. But the numbers of women carrying normal fetuses are much higher (2,498), so that in our imaginary sample, twenty-five women with normal babies will test positive, while the remaining 2,473 will get the correct result. This makes the chance of a woman carrying a Down’s syndrome baby if she tests positive only about 7% (two out of the total twenty-seven who received positive test results). In addition, there is a two in one thousand chance of amniocentesis inducing a miscarriage, so four to five of the women across the two groups will lose their babies. Again, given the tiny numbers in the first group, let’s assume these are all in the largest group (the 2,473 women with negative results).

Figure 1 Are tests for Down’s syndrome justified?

What exactly do these numbers mean in practice? Looking on the bright side, as we promised, if you’re a twenty-five-year-old pregnant woman who tests positive for Down’s syndrome on the basis of an amniocentesis test alone, then your chances of having a normal baby are still 93%! Makes you wonder why you took the test in the first place, doesn’t it (especially when you add the small risk of miscarriage into the mix)? And if this is the reasoning for an individual, the case for making amniocentesis-for-all a public health policy is even smaller. If the cost of each test is $100, we’ve just spent a theoretical $250,000 on a test that led to five miscarriages (with the further expenditure that entails) and twenty-seven repetitions of the test at another $2,700, plus the not insignificant emotional stress until the results of the second test are known. That’s assuming of course that all twenty-seven women who tested positive follow our advice from the previous chapter, which seems highly pertinent here, and get a second opinion. If not, some unnecessary – and even more costly – terminations may take place. Meanwhile, one or both of the two women with the “true positives” may well decide to proceed with the pregnancy anyway – on religious or other grounds. Was it worth it? We let you, the reader, decide.

And that’s the whole point. Any patient, undergoing any tests (especially if they’re for purely preventive reasons) should have access to the relevant data and reasoning. The doctor should run through diagrams like figure 1, particularly highlighting the issue of false positives – which occur with all medical tests – in order to both inform the patient and avoid unnecessary alarm. The danger comes from blindly following health-policy directives and slipping into the illusion of certainty – or worse, fog of ignorance and fear – that test results all too often induce.

Now for our second example. In his excellent book Calculated Risks: How to Know when the Numbers Deceive You, the psychologist Gerd Gigerenzer highlights a second important example: screening for prostate cancer using a prostate-specific antigen (PSA) test.

people who take PSA tests die equally early and equally often from prostate cancer compared with those who do not. One cannot confuse early detection with mortality reduction. PSA tests can detect cancer, but because there is as yet no effective treatment, it is not proven that early detection increases life expectancy. [. . .] The test produces a substantial number of false positives, and therefore, when there is a suspiciously high PSA level, in most of these cases there is no cancer. That means many men without prostate cancer may go through unnecessary anxieties and often painful follow-up exams. Men with prostate cancer are more likely to pay more substantial costs. Many of these men undergo surgery or radiation treatment that can result in serious, lifelong harm such as incontinence and impotence. Most prostate cancers are so slow growing that they might never have been noticed except for the screening (out of 154 people with prostate cancer only twenty-four die of the disease). Autopsies of men older than fifty who die of natural causes indicate that about one in three of them has some form of prostate cancer. More men die with prostate cancer than from prostate cancer.7

A recent study, published in the Journal of the American Medical Association reaches similar conclusions about the value of screening with CT scans. The researchers tested 3,246 current and former smokers and found nearly three times as many people with lung cancer than would have been predicted. Yet there was no corresponding reduction in advanced lung cancers or even deaths. “Early detection and additional treatment did not save lives, but did subject patients to invasive and possibly unnecessary treatments,” said the authors.8

It’s no wonder that more and more medical experts are advising against cancer screenings altogether. In a recent book, Dr. H. Gilbert Welch, an American physician, claims that screenings tend to miss the fastest-growing, most deadly cancers, while cancer-free patients with abnormal screening results often endure endless, sometimes risky testing that leads to unnecessary treatment and yet further superfluous tests.9 Some of his colleagues in the profession are going further, questioning surgical procedures in the same way. Dr. Norton M. Hadler is urging the US medical establishment to rethink some of its most basic beliefs about cardiovascular care. In particular, he says that by-pass surgery “should have been relegated to the archives fifteen years ago.” The procedure, he continues, “extends life or prevents further heart attacks only in a small percentage of patients – those with severe disease.”10 Another physician, L. David Hillis, supports this conclusion and extends it to angioplasty, in which narrowed blood vessels are expanded and then, typically, propped open with metal tubes. As he points out: “People often believe that having these procedures fixes the problem, as if a plumber came in and fixed the plumbing with a new piece of pipe, but it fundamentally doesn’t fix the problem.”11

It’s that illusion of control again. Our desperate, innate desire to eliminate all threatening uncertainty can be the only explanation of why we’re repeating the medical mistakes of the past instead of learning from them. As fast as we get rid of old recommendations, such as annual health checks, regular mammography screening and PSA, we seem to be introducing new ones like advising amniocentesis for all pregnant women.

If this sounds a bit negative again, it wasn’t meant to. We refer you to our previous positive conclusion to trust your own assessment of how you feel. In most cases, if you feel good, there’s no need to take a test to see if you’ve got an illness. To that we now add another active recommendation: all aspects of your personal healthcare should be guided by sound reasoning based on empirical evidence. Find out the dangers, as well as the benefits, of undergoing testing, a course of drugs, or a medical procedure.12 This approach, championed by Dr. David Eddy among others, has become known as “evidence-based medicine.”

We’d like to extend our advice to governments as well as individuals. In the same way that government agencies license drugs (for example the Food and Drug Administration in the USA), they should also make up-to-date recommendations about medical procedures. That way, we’d know an independent, official body had looked at the available evidence and reached a bias-free conclusion. Knowing the world of medical research as we now do, we wouldn’t necessarily hold them to it for long! But at least our task of actively managing our own health by weighing up the evidence would be simpler.

Getting hold of the evidence isn’t always simple, as the classic case of Cesarean section shows. This, as most people know, is a form of childbirth that involves making a surgical incision to deliver one or more babies. The idea behind the procedure is that it’s used when a “normal” delivery would lead to dangerous and possibly life-threatening complications for the mother and/or child.

Although most Cesarean sections these days don’t require a general anesthetic, it is without doubt a major abdominal operation that shouldn’t be taken lightly. The UK National Health Service estimates the mortality risk of a Cesarean section as three times that of a vaginal birth. On the other hand, this isn’t a fair comparison, as the women having surgery tend to be the ones at higher risk. And anyway, the mortality rates for both types of birth have dropped steadily, at least in the developed world. As we said, finding and interpreting the evidence isn’t always simple.

Nevertheless, Cesarean sections have some distinct disadvantages. From the mother’s point of view, the recovery time is much greater than for a “normal” birth. The operation also leaves an unsightly scar and brings an increased risk of infection. From the baby’s perspective, the anesthetics and drugs administered to the mother sometimes mean a sluggish start to life, occasionally with breathing problems. And breastfeeding – with all its proven benefits – tends to be more difficult after a Cesarean, partly because the mother’s mobility is reduced. From the healthcare provider or insurer’s perspective, there’s also a major extra cost to perform an operation. In the longer term, a study recently published in the journal Obstetrics and Gynaecology found that women who had multiple Cesarean sections were more likely to have problems with later pregnancies.13 The conclusion was that women who wanted large families should have vaginal deliveries if possible. And this time, the sample of 30,132 Cesarean births seems statistically ample!

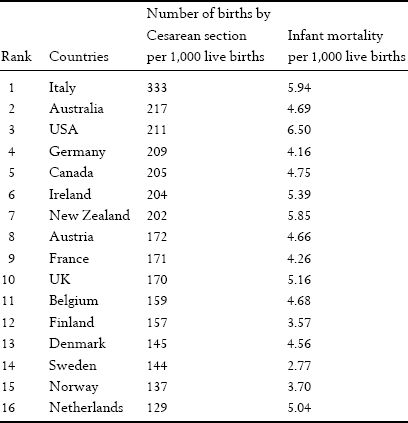

So why are Cesarean sections so incredibly popular – and apparently getting more so? Some recent estimates put Cesarean births at over 30% of the total in the USA in 2005 – an increase of 46% since 1996.14 Why too is there so much variation from one developed country to the next, as table 3 reveals?

Are Italian doctors justified in performing one-third of births by Cesarean section? Or are their Dutch colleagues right – with a rate lower than 13%? Clearly, it’s highly unlikely that they’re both correct, as the women of these two countries can’t have significantly different medical needs. Curiously too, table 3 shows a positive relation between rates of Cesarean births and infant mortality.16 As we said earlier, this is a tricky issue to unravel, but it’s interesting that Sweden, with one of the lowest rates of Cesarean births, has by far the lowest infant mortality rate while that in Italy is one of the highest.

Perhaps some of the answers can be found by looking at the variation in Cesarean rates within countries. Hollywood and celebrity parents famously tend to opt for the operation. And in general, the so-called “elective” Cesarean tends to be a privilege of the rich. A recent study of births in three Greek hospitals – two public and one private – concludes: “The CS rate in the public hospitals was 41.6% (52.5% for Greeks and 26% for immigrants), while the CS rate in the private hospital was 53% (65.2% for women with private insurance and 23.9% for women who paid directly).”17

Table 3 Births by Cesarean section (year 2000): various countries15

There are two possible interpretations. The first – more charitable – explanation is that a Cesarean section is the ultimate “illusion of control”. Rather than waiting for nature to take its course, those doctors and parents with the means to do so slot this time-efficient method of giving birth into their busy schedules. Ironically, by seeking certainty, these mothers are often exposing themselves to greater risk – but that’s their business (if possibly a little unfair on the baby, who has no say in the matter).

The other interpretation is less generous toward the medical profession. Could it possibly be that doctors’ decisions are influenced by the lure of higher revenues and bigger profits?18 Far be it from us to cast aspersions on their ethics, but there are many from within the medical profession who do so without prompting. Dr. David Walters, head of cardiology at the University of California in San Francisco, claims that conflict of interest is a major issue in his field, where doctors perform about 400,000 by-pass operations and one million angioplasties a year, creating a heart surgery “industry” with an estimated $100 billion annual turnover.19

And so we return to our positive assertion that patients deserve a more evidence-based approach to choosing their individual treatment. If each country or grouping of countries could have some kind of independent, not-for-profit “auditor” of the evidence, so much the better. The assumption that each of us has to fight is that extra healthcare, extra medical intervention, and extra testing mean more health and a longer life. On the contrary, perhaps. As Michael Moore, in his acclaimed 2007 documentary Sicko, and many other commentators point out, the longer you can stay outside the healthcare system, the longer you avoid its many risks to your health – from human error to deadly, flesh-eating hospital super-bugs.

Mainstream medical care is based on the assumption that what a physician decides is, by definition, correct. Although many decisions are indeed right, there are plenty of others that are highly questionable. So it’s important to find a way to reassure patients that they’re receiving the best medical care for their own specific cases – and that such care does not reflect inappropriate interests. Once again, we advocate the approach of evidence-based medicine. Moreover, in order to avoid any suspicions of conflict of interest, there should be some independent, non-profit organization, like the US Food and Drug Administration or the Cochrane Collaboration, to verify or even audit the empirical evidence. Most importantly, patients should be able to get information about the benefits, dangers, and costs of the various forms of medical care available to them and not be “forced” – through fear or ignorance – into specific treatments.

The problem is that higher spending on health does not imply improved medical care, as Dr. Elliott S. Fisher, professor of medicine at Dartmouth Medical School in New Hampshire, found out. He had assumed that people in areas with low health expenditures would have worse health than those in regions where spending was up to twice as high. However, the opposite turned out to be true. His conclusion: “Patients have a substantial increased risk of death if cared for in the high-cost systems.”20 The reason is that additional physician visits and testing often lead to unnecessary procedures and hospitalizations, which carry equally unnecessary risks. This is a classic example of the paradox of control.

It is important at this point to put our concerns about medical practice in perspective. We don’t question that the medical profession has had remarkable successes and made incredible progress over the years. Think of all those wonder drugs we read about in the papers. No one can deny that the world is far better off for the discovery of drugs such as aspirin and quinine. In fact, both have been around long enough for us to be absolutely certain that they work (even if excessive claims are sometimes made for the ability of aspirin to prevent heart attacks and various forms of cancer). Then there are antibiotics, which have transformed society by eradicating not only the infection but also the terror of tuberculosis. Today, the innovations continue with the development of synthetic drugs that allow people with, for example, serious thyroid deficiencies to live perfectly normal lives.

Surgical techniques have also made great strides. What neurosurgeons can do today could scarcely be imagined a generation ago. And it’s hard to believe that it was only just over forty years ago (in 1967) that Dr. Christiaan Barnard performed the first ever human heart transplant. Key-hole surgery too has transformed many lives – and the careers of professional sportsmen and women who are no longer sidelined for months by certain types of injuries.

At the same time, countless erroneous medical theories have been discredited. It was only two hundred years ago, for instance, that deliberate bleeding was supposed to cure all manner of ills. And nowadays, it’s rare for a doctor to make a diagnosis by examining the patient’s tongue with great care – common practice just a generation or so ago.

We take no issue with these particular developments. Nor do we contest that general medical knowledge has increased and that diagnosis is far more accurate than ever before. Our arguments are with the way in which medical data are so often interpreted. But most of all, we dispute doctors’ and patients’ refusal to accept the uncertainty that inevitably remains to this day. As a society, we could make much better use of what we already know – even though this knowledge is often imperfect. Consider, for example, what a difference it would make if people understood the simple fact that medical tests can incur two kinds of errors (the false positives and the false negatives that we described earlier in this chapter), each with extremely serious implications for our well-being.

Back in 1923, the French writer Jules Romains wrote a comic play about Dr. Knock, who purchases an unprofitable village medical practice in rural France. He then proceeds to diagnose practically everyone in the village with an illness and prescribes a cure for each character at a price proportional to their income.21 But is this the stuff of provincial comedy – or an ongoing tragedy on an international scale? Nearly a century later, the doctor and commentator H.G. Welch, whose book we referred to above, writes in The New York Times, that over-diagnosis is making people ill.

For most Americans, the biggest health threat is not avian flu, West Nile or mad cow disease. It’s our healthcare system. You might think this is because doctors make mistakes (we do make mistakes). But you can’t be a victim of medical error if you are not in the system. The larger threat posed by American medicine is that more and more of us are being drawn into the system not because of an epidemic of disease, but because of an epidemic of diagnoses. [. . .] But the real problem with the epidemic of diagnoses is that it leads to an epidemic of treatments. Not all treatments have important benefits, but almost all can have harms. Sometimes the harms are known, but often the harms of new therapies take years to emerge.22

Our purpose is not to criticize any one country’s doctors or even the medical profession in general. As we’ve said before, it’s thanks to medical science that people now live longer and more healthily than ever before in history. We’d just like to make the point that the time has come for a worldwide change – both on the part of the healthcare industry and its consumers.

In general, for those who feel healthy (and aren’t pregnant), our first piece of advice, based on the overwhelming empirical evidence, is to stay away from doctors. Second, when people really have to turn themselves into patients, they should recognize the inherent uncertainty of medical science. This brings us to our third piece of advice, which is to make yourself as informed as possible about any diagnosis, test, or treatment you are going to receive. There’s also some parallel advice for the medical profession, which should be to do everything in its power to help its customers make informed decisions. Finally, if possible, get that proverbial second (or even third) opinion. And even then, if it’s not an emergency, wait a few weeks before taking action. You can use the extra time to source further information and to achieve a calmer, more rational standpoint.

Today, we have many sources of information at our fingertips. Examples include the Foundation for Informed Medical Decision Making (www.fimdm.org) in the USA, a non-profit organization that helps people get hold of the information they need to make sound decisions about their health, or an agency for healthcare research and quality, supported by the US Department of Health and Human Services (www.ahrq.gov/clinic/uspstfix.htm). In the UK, there is information from NHS Direct (www.nhsdirect.nhs.uk), a multi-channel information source provided by the state. There are also specialized information sources and web tools for making decisions about specific conditions. According to the Foundation for Informed Decision Making, patients who get the full story – as opposed to listening simply to what the doctor tells them – tend to opt for less intervention. Studies carried out by the Foundation and others show that up to 60% of people change their decision once they have all the information available.23

Of course, we hasten to add, we’re not recommending web-based self-diagnosis – which has become a true plague of modern medicine. That would be a good deal worse than passively accepting a doctor’s diagnosis. Instead, show your physician that you’re well informed and impress them with some penetrating questions, like the following:

• Can you tell me the benefits and dangers of the treatment you’re proposing?

• Are there alternatives? If so, what are the respective pros and cons of each of them?

• What are the conclusions of any empirical research on the treatment or its alternatives?

• Are the side effects of the drugs I will need to take known? And if yes, what are they?

• Has any independent organization like the Cochrane Collaboration audited the research findings?

• What if I do nothing? Will it affect my quality of life or years left to live?

• If I go ahead with the treatment, will I need further therapy in the future?

• Is the cost of the treatment likely to be covered by my private insurance (or national healthcare system)? If not, how much will the total cost be?

You won’t simply get answers to help you make an informed decision. You should also gain the respect of your doctor! Ideally, you will reach a position where you’re making a decision yourself with the help and support of your doctor – free of all bias and snap judgments. In his book How Doctors Think,24 Dr. J. Groopman advises precisely this course of action. So once again there’s a precedent for what we’re saying from within the medical profession. In addition, be prepared when you visit your doctor. Follow the advice of Dr. Terrie Wurzbacher25 and pre-empt any important questions about your health before you’re asked. Write down your answers even. Are you taking any medication or supplement, whether off-the-shelf or prescribed? Are you on a diet? How much alcohol do you drink? How much exercise do you get? Are you under stress – or have you endured severe stress in the past? Do you suffer from any allergies? Do you have a history of certain problems in your family? If your doctors have all this information and more at their fingertips, they can concentrate on discussing your current condition and explaining the pros and cons of the various treatments available.

It is important to emphasize that neither you nor your doctor can reduce the uncertainties associated with medical conditions, test results, diagnoses, treatments, or prognoses. However, what you – the patient – can achieve is control over the process by which the medical decisions that affect you get made. Taking this active role can, we believe, reduce the negative dimensions of hope (that it’ll all work out in the end), fear (of pain or death), and greed (for a long and healthy life). By accepting that you can’t always control your health through blind faith in science, you’ll improve your ability to deal with most medical problems. You could even come face to face with a life-or-death instance of the paradox of control.

Will our advice make you as “healthy, wealthy, and wise” as in the old nursery rhyme? Well, it will certainly make you wiser and ought to make you healthier. As for wealthier, read on into the next two chapters about money and investments.