It will fluctuate.

John Pierpont (“J.P.”) Morgan

(1837–1913), when asked what the

stock market was going to do

Money talks . . . and talks and talks. So much so that we can’t always figure out what it’s saying. Dinner party conversations invariably turn to tales of investment riches (or rags), while experts – from financial journalists to fund managers – claim to be able to see patterns in the stock market. The big challenge is how to separate the patterns from the background “noise.”

In particular, how are we – the man or woman on the street – supposed to manage our savings in the midst of all this chatter? This is probably one of the most crucial aspects of our personal Fortune – and one of the most difficult to administer. Even if we’re not direct dabblers in the stock market, many of the financial products we buy, such as pension funds, come from the financial markets. Whether we like it or not, we are investors.

This chapter is devoted to proving two facts to you, the investor. They’re two pretty big facts, so here they are up front. First, no one can predict specific outcomes of the financial markets consistently across time. The consequence is that investors who believe that they or others can predict market outcomes can lose a lot of money. When it comes to finance, illusions of control are very costly. Second, even though, in the short and medium term, there’s no way of telling which way the markets will go, in the long run, they do exhibit consistent upward trends.

Back in 1987, when shoulder pads were all the rage, a book entitled The Great Depression of 1990 came out. The author, Dr. Ravi Batra, wrote:

I am an economist, trained in scientific analysis, not a sensationalist or a Jeremiah. Yet all the evidence indicates that another great depression is now in the making, and unless we take immediate action the price we will have to pay in the 1990s is catastrophic.1

Dr. Batra was lucky. His book sold hundreds of thousands of copies. But the rest of us were even luckier. His prediction was dead wrong. The 1990s saw the second biggest stock market boom in US history. During the decade, the Dow Jones Industrial Average index of leading shares (DJIA) grew from 2,753 to 11,358. In other words, $10,000 invested in January 1990 across all thirty of the companies whose shares are tracked by the index would have grown to $41,257 at the end of 1999. During the same period in the UK, the FTSE 100 stock market index published by the Financial Times almost tripled in value, rising from 2,423 to 6,930. Dr. Batra’s doomsday never arrived.

So it’s no surprise that, come 1999, people were writing very different kinds of books from Dr. Batra. These included: Dow 36,000: The New Strategy for Profiting from the Current Rise in the Stock Market by James K. Glassman and Kevin A. Hassett;2 Dow 40,000: Strategies for Profiting from the Greatest Bull Market in History by David Elias;3 and Dow 100,000: Fact of Fiction by Charles W. Kadlec.4 Here’s a quote from the first of these (also the most modest in its claims).

A sensible target date for Dow 36,000 is early 2005, but it could be reached much earlier. After that, stocks will continue to rise, but at a slower pace. This means that stocks, right now, are an extraordinary investment. They are just as safe as bonds over long periods of time, and the returns are significantly higher.

(Glassman and Hassett, p.140)

Between 2000 and 2003, the worldwide value of equities declined by $13 trillion (about $2,000 for every person in the world), while the combined value of the New York Stock Exchange and NASDAQ alone fell by $9.3 trillion. The DJIA hit a low of less than 7,300 in October 2002 and, on November 20, 2008, was more than 35% lower than the peak of 11,722 it reached ten years earlier. Worse still, on March 9, 2009 the DJIA hit a low of 6,700, having fallen close to 53% since its high of 14,165 reached on October 9, 2007. So will the DJIA ever reach 36,000 let alone 100,000? Probably yes, given enough time, but (although this sounds dangerously like a prediction on our part) we doubt it will get there any time soon.5

Only one year after the various Dow optimists wrote their books, Yale economist Robert Shiller added another tome to the library of forecasting. In Irrational Exuberance, he argued that the stock market was greatly overvalued (the DJIA was about 11,000 at the time) and had all the “classic features of a speculative bubble: a situation in which temporarily high prices are sustained largely by investors’ enthusiasm rather than by consistent estimation of real value.”6 While he didn’t predict an imminent bursting, he concluded that the outlook for the stock market for the next ten or twenty years was “likely to be rather poor – even dangerous.”

So if book writers are not good forecasters, what about the IMF and all the other agencies that specialize in forecasting? They have not done any better. The following are a few quotes from the IMF:

• April 2007: Notwithstanding the recent bout of financial volatility, the world economy still looks well set for continued robust growth in 2007 and 2008. While the U.S. economy has slowed more than was expected earlier, spillovers have been limited, growth around the world looks well sustained, and inflation risks have moderated.

• October 2007: The problems in credit markets have been severe, and while the first phase is now over, we are still waiting to see exactly how the consequences will play out. Still, the situation at present is one with threats rather than actual major negative outcomes on macroeconomic aggregates. At this point, we expect global growth to slow in 2008, but remain at a buoyant pace.

• April, 2008: Global growth is projected to slow to 3.7 percent in 2008, ½ percentage point lower than at the time of the January World Economic Outlook Update and 1¼ percentage points lower than the growth recorded in 2007. Moreover, growth is projected to remain broadly unchanged in 2009. The divergence in growth performance between the advanced and emerging economies is expected to continue, with growth in the advanced economies generally expected to fall well below potential. The U.S. economy will tip into a mild recession in 2008 as the result of mutually reinforcing cycles in the housing and financial markets, before starting a modest recovery in 2009 as balance sheet problems in financial institutions are slowly resolved.

• October, 2008: The world economy is entering a major downturn in the face of the most dangerous financial shock in mature financial markets since the 1930s. Global growth is projected to slow substantially in 2008, and a modest recovery would only begin later in 2009. [. . .] The immediate policy challenge is to stabilize financial conditions, while nursing economies through a period of slow activity and keeping inflation under control.

Business experts did not fair better either. Business week, in its annual survey of business forecasters, summarized their predictions as follows:

The economists project, on average, that the economy will grow 2.1% from the fourth quarter of 2007 to the end of 2008, vs. 2.6% in 2007. Only two of the forecasters (34 in total) expect a recession.

(Business Week, Dec. 20, 2007)

It does not seem that the seriousness of the financial crisis, or the resulting economic recession, was predicted by the great majority of forecasters. The consequences, so far, have been big surprises, huge losses, many bankruptcies and several trillions of dollars of taxpayers’ money being spent in an attempt to fix the problem. The big question is, therefore, what is the value of economic and financial forecasting when it completely missed the most serious financial crisis that hit the world economy and provided no warning of its arrival and seriousness?7

So many experts, so many opinions. With hindsight, it’s easy to know which of them to believe. As the 2000–2003 correction showed, Shiller’s measured pessimism was the most accurate of those we’ve mentioned. Furthermore, the eminent economist was right again in the 2005 second edition of his book,8 where he maintained that the stock markets were still overvalued. But don’t tell your stockbroker to sell, sell, sell just yet. After all, Glassman, Hassett, Elias, and Kadlec are all highly regarded stock market experts too. If they turn out to be right in the end, you’ll be missing out on a great opportunity.

Perhaps it’s wrong to rely on economic and financial forecasters for advice. Let’s look instead at some real-world experts, who put their money (or at least other people’s money) where their mouths were.

Back in 1994, when shoulder pads were finally going out of fashion, a former bond trader for Salomon Brothers called John Meriwether started his own firm, the Long Term Capital Management Fund (LTCM). He had everything going for him: a stellar reputation, millions of dollars, and the best connections. Indeed, he assembled an all-star team including two famous economists (Myron Scholes and Robert Merton), a former vice-chairman of the Federal Reserve Board (David Mullins), and a host of highly experienced, greatly respected traders.

The formula for success was simple. The quantitative models of the academics, combined with the know-how of the practitioners, would achieve substantial returns with minimal risk. In no time at all, LTCM had raised $1.25 billion from about eighty investors – who each put in a minimum of $10 million. Many of the investors were themselves “experts”: banks, bankers, university endowment funds, and well-known executives.

For a while, the formula seemed to be working. Returns were well above the market average. In 1994, LTCM earned a huge 28% on its investors’ capital, rising to 59% in 1995 and 57% in 1996. With earnings like these, the fund was able to borrow vast sums of money to make its own investments and boost profitability yet further. So much for minimal risk. Then, in 1997, Scholes and Merton’s mathematical models had a bad year. Returns were about the same as the market average and Meriwether was forced to repay $2.7 billion to investors. But there was no need to panic – at the beginning of 1998, LTCM still had assets exceeding $130 billion, while its portfolio of derivatives was worth close to $1.2 trillion.

Perhaps everything would have been fine, if it hadn’t been for a series of events that began in April 1998, including the devaluation of the ruble and the debt moratorium declared by the Russian government. On a single day, August 21, 1998, LTCM lost more than half a billion dollars. Just over a month later, the fund had lost most of its equity and was teetering on the brink of default. Worse than that, having borrowed $1.3 trillion, the firm’s imminent demise was a threat to the entire global financial system. On September 28, 1998, a consortium of financial organizations, led by the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, stepped in with a $3.6 billion rescue fund. By the end of 1998, LTCM had ceased to exist.

The point of the story is not so much that the brilliant academics and their array of expert colleagues and customers got their figures wrong. It’s more that nobody else in the financial community foresaw LTCM’s plunge from grace, even just a few months before it happened. And there’s a punchline too: in 1997, just as things were beginning to unravel for them, Scholes and Merton were awarded the Nobel Prize for economics – for their work on controlling financial risk.

The following description once stood proudly on the website of Amaranth Advisors.

We are a multi-strategy hedge fund. Amaranth’s investment professionals deploy capital in a broad spectrum of alternative investment and trading strategies in a highly disciplined, risk-controlled manner. Our ability to effectively pursue a variety of investment strategies combined with the depth and strategic integration of our equity, credit and quantitative teams, supported by a world-class infrastructure, are some of the key strengths that distinguish and define Amaranth. [. . .] We are committed to exploring and developing new ideas, moving nimbly and effectively within an ever-changing investment landscape, thereby staying fresh, current – unfading.

Amaranth is a plant with flowers that seem to last forever (the name’s origins are in the Greek word “amarantos,” which means “unfading” or “indestructible”). But this particular Amaranth faded fast – and suddenly. It collapsed in September 2006 after losing close to $6 billion in a single week. The fund had been betting heavily on natural gas futures. This paid off handsomely in 2005, after Hurricane Katrina had cut production and prices doubled in less than five months. But good weather and high gas stocks in 2006 sent prices plummeting. On September 29, 2006, the founder of Amaranth, Nicholas Maounis, wrote to the fund’s investors notifying them of its termination. On October 1, 2006, just as the fashion magazines were announcing the return of shoulder pads, the financial press reported that Amaranth had appointed liquidators to return what they could of the remaining assets to investors. It really was that quick.

The dictionary defines “hedge” as “to enter transactions that will protect against loss through a compensatory price movement.” Yet Amaranth did quite the opposite. It seems as if its experts learned nothing from the catastrophic fall of LTCM and the resulting guidelines – which were readily available even to amateurs. These state that no more than one-tenth of a fund’s assets should be placed in a single type of speculative investment. Yet Amaranth brazenly placed huge bets on one highly speculative commodity – natural gas.

LTCM and Amaranth are not alone in financial history. In fact there are hundreds of other funds that have ceased operating because they lost so much money. At the beginning of 2007 there were close to 8,500 hedge funds in the USA with assets exceeding $1.3 trillion. There were also 8,100 mutual funds with assets of $10 trillion. If history repeats itself, many of them won’t exist in a few years’ time, perhaps because of mergers, but most often because they underperform the market.

Here are some of the figures that aren’t included in the fund managers’ slick sales projections. In 2001, there were 1,921 diversified stock funds in the USA. Five years later, 543 of them were gone. Between 1970 and 2006, 223 US equity funds went under, many of them associated with highly reputable financial brands. The S&P/InterCapital Dynamics fund lost 95.7% of its value, while the Steadman Technology & Growth, CitiFunds Emerging Asian Markets Equity, and Morgan Stanley Gold B funds all failed. In addition, many firms have lost vast amounts in various forms of investments and trading. Barings Bank collapsed after one of its traders, Nick Leeson, famously lost nearly a billion dollars in just two months at the beginning of 1995. And in 2008 this feat was surpassed by a new rogue trader, Jérôme Kerviel of Société Générale, who allegedly lost €4.9 billion (equivalent to $7.4 billion at the time) of his employer’s money. Allied Irish Bank lost $691 million in unauthorized trades in its Baltimore subsidiary. Sumitomo of Japan lost millions of dollars through speculative trading, as did Metallgesellschaft of Germany, Showa Shell (a subsidiary of the well-known oil company), Kidder Peabody (an investment bank owned by GE) . . . the list goes on. And these are just the ones that made it into the newspapers – the tip of a multi-billion-dollar iceberg.

Where does that leave you the investor? Probably with very cold feet indeed. Perhaps the solution is to hand-pick a few individual stocks. But which ones? Time to consult the experts again. Fortune magazine has been hailing one particular company as “America’s most innovative” for six consecutive years now. The McKinsey Quarterly is also a fan and says it’s an example of how innovative companies can surpass their conventional competitors. And there are lots of business-school case studies explaining exactly how this organization became so successful. International management guru Gary Hamel goes so far as to say that the company in question “has institutionalized a capacity for perpetual innovation.”9 What’s more, profits were $1 billion last year, while its total stock market value has just reached $186 billion. Oh, and its revenues have surpassed $100 billion last year, making it the seventh biggest company in the Fortune 500.

The catch? We’ve gone back in time to early 2001 and the company in question is Enron. Buy shares now at $81.39 and in ten months’ time, when Enron files for bankruptcy, they’ll be worthless. It turns out that the biggest “innovations” of the world’s top energy company are in the creative accounting department. Enron is overstating its revenues and profits, while siphoning huge sums of money from its shareholders to some of its top executives and their friends. Like LTCM, Enron is known for its sophisticated risk management techniques. But they won’t save it from insolvency – or its executives from prison. The business school boffins’ case studies will soon mysteriously disappear from the back catalogues and the journalists will be writing very different stories about Enron.

But in early 2001, no one can tell you this. Nor will they predict the fall of WorldCom, which will beat Enron’s record for value destruction when it files for bankruptcy only seven months later. The two companies’ stories are strangely similar. Enron was formed from the merger of two traditional gas utilities in 1985, while WorldCom started in 1983 as a small company that would benefit from the break-up of AT&T and the liberalization of the US telecoms market. Thanks to acquisitions, it grew to become the second biggest telecoms company in America. Bernie Ebbers, its charismatic and visionary CEO, was the darling of Wall Street. In the middle of 1999, its stock reached a high of over $64 and the company was valued at $180 billion. But when the company finally filed for bankruptcy on July 21, 2002, it had debts exceeding $40 billion.

The reasons for WorldCom’s huge losses were multiple. The internet boom of the late 1990s had increased demand for telecoms services and started a race to lay new fiber-optic cables. The dotcom bust exacerbated the resulting overcapacity and prices dropped by a factor of seven or eight in a period of just a few years. WorldCom’s earnings and share prices started to plummet. Ebbers and his CFO were powerless to stop the downward spiral . . . until they started cooking the books. When KPMG came in to audit in the spring of 2002, they uncovered a $3.8 billion accounting fraud. It was Enron all over again, only bigger.

Again, it is not just that these were the two biggest bankruptcies in history. It’s not that thousands of investors lost billions of dollars and 1,500 creditors went unpaid either. Nor that nearly 100,000 employees lost their jobs, their savings, and their pensions (which had been invested in the companies). What we’re saying is that absolutely nobody was able to warn these innocent victims of the impending disaster. And the same forecasters failed to spot other dark clouds on the investment horizon. In 2002 there were thousands of other corporate bankruptcies: four major cases (Conseco, Global Crossing, Adelphia, and K-Mart), involving nearly $130 billion in assets; 259 additional public companies; and 37,000 other businesses in the USA alone. And there are similar tales of unforeseen business tragedy from Europe: Parmalat, Marconi, Swissair, Royal Ahold, to name just a few.

Enough doom and gloom. Table 4 shows a short list of some of the most exceptionally successful USA companies at the time of writing, together with the market capitalization of each of them in January 2008 (that is, how much all their shares were valued by the stock market).

The total value of the eight companies at the beginning of 2008, $1.356 trillion, was more than the total GNP of the world’s sixty-five poorest countries, which have a population of over a billion people. What’s more, most of this wealth accumulated fairly recently, in historical terms at least. If you’d bought $10,000-worth of Wal-Mart shares in January 1977, your investment would have grown to $35 million just thirty years later. Similarly, $10,000 invested in Dell stocks at the beginning of the 1990s would have given you $10 million at the end of the decade. Microsoft shares went up to 600 times their original price in just ten years too.

Table 4 Market values of eight successful companies (January 2008)

Market capitalization: January 2008 (in $ billions) |

|

GE |

349 |

Microsoft |

311 |

Wal-Mart |

193 |

Berkshire Hathaway |

196 |

190 |

|

Dell |

46 |

eBay |

38 |

Yahoo |

33 |

Total |

1,356 |

The uplifting news is that the immense wealth generated by these and other successful companies more than compensates for the value destroyed in the high-profile bankruptcies. The only snag is that the riches are often unforetold too. With hindsight, it’s easy to explain success. But when IBM was offered a significant share of Microsoft for only a few hundred thousand dollars, executives turned the offer down.

Of course, there have been some extremely successful investors over the years. The careers of Warren Buffett and George Soros are legendary, even outside financial circles. But do they have the gift of clairvoyance or did they just get lucky many times over? And what of today’s stars? Peter Lynch, John Neff, Bill Miller, and Anthony Bolton have brought great wealth to their clients to date. Will they continue to do so? It might seem reasonable to assume that past successes are a good indication of future returns. But that was exactly where Georgios went wrong . . .

At the end of 1973, Georgios, an extremely successful self-made Greek industrialist asked one of the authors of this book to forecast the price of gold for the next decade, so that he could figure out exactly how much bullion to buy. Georgios had made his fortune in the steel business, which had thrived thanks to the post-war Greek property boom, caused in turn by the country’s rapid industrialization. Through his business, Georgios had become aware of the rising prices of metals and other commodities, and he believed that gold prices would increase much more quickly than inflation.

This wasn’t such a crazy notion. Inflation in Greece was rampant at the time, interest rates in government-owned banks barely outstripped it, and strict exchange controls prevented Greeks from converting their money into other currencies. However, to protect themselves from soaring prices, Greeks were allowed to buy gold from the central bank. Many of them did just that, particularly as there were no stock markets or other places to invest their hard-earned cash. Georgios was one of the many. He’d bought and sold gold many times in the past – and still owned a fair amount. Georgios also believed that the termination of the Bretton Woods System about a year and a half earlier would liberate trading and lead to substantial price increases.

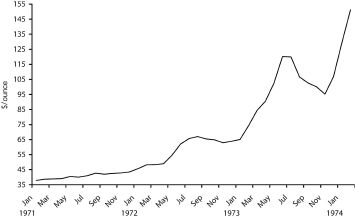

The Bretton Woods agreement of 1946 had effectively fixed the price of gold at $35 an ounce. It came to an end on August 15, 1971. Up until that date, gold had principally been used as a reserve for governments to issue paper currencies. Nevertheless, in anticipation of free trading, prices began increasing from January 1971(having been more or less flat since 1800) – as is clear from figure 2.

In March 1974, the author showed figure 2 to Georgios, who was delighted. He also showed him the yearly real gold prices (adjusted for inflation) since 1800. These had been fairly constant for the past 173 years, a fact that Georgios dismissed as irrelevant since the price had been controlled. The author agreed with him, but – as a professional statistician with no training in clairvoyance – felt he’d hit a dead end. There was simply not enough relevant data to go on. So, every month, as soon as the latest information on the price of gold became available, he sent a telegram (strange as it may seem, in those days there were neither fax machines nor overnight courier services, let alone e-mail) to Georgios, updating the graph. He also sent him every article that appeared in the trade press or economic journals. Most of them predicted continued price rises. Georgios was convinced that gold would cost over $1,000 an ounce by the end of the decade – and every extra piece of information he received only added to his conviction. He kept on buying bullion even when the price was reaching all-time historical highs. Georgios refused to listen to talk of bubbles that burst. His mantra was: “No one has ever lost money in gold.”

Figure 2 Monthly gold prices, January 1971 to February 1974

But, you guessed it, Georgios did lose money in gold. The price peaked at about $675 in September 1980, then started to fall as fast as it had risen.10 And apart from a small recovery in the late 1980s, it just kept on falling until 1999. Unfortunately for Georgios, gold stored in a bank vault also attracts hefty storage charges. And, unlike many other kinds of investments, lumps of shiny metal sitting underground don’t offer annual dividends. He finally bowed to the inevitable and sold up in 2000. His total investment over the years had been $9.1 million. If only he’d sold in 1980, he’d have made more than $18 million. Even if he’d waited until 1982, he’d have come out $6.5 million up. But Georgios didn’t. In the end he made a loss of nearly $1 million. Hindsight brings even less consolation. We now know that he sold at exactly the wrong time. Figure 3 shows Georgios’s graph, updated to 2007.

As you can see, since 2000 gold prices have been on the up again. Many experts and newsletters are once again making predictions of a new El Dorado. On December 8, 2006, Paul van Eeden of Toronto, one of the foremost authorities on the gold market, announced, “I say with a very high level of confidence that gold prices will go to $1,000 an ounce in the next two to five years.” Although Paul van Eeden’s forecast turned out to be correct as the price of gold exceeded $1,200 in April 2010, the author for one is sticking to his story: we just don’t know – and neither does anyone else.11

Figure 3 Real gold prices (constant 2006 dollars)

If not gold, what should Georgios have invested in? Taking a very historical and long-term perspective, the answer is obvious. But before we reveal it, let’s get the lie of the investment landscape.

Globally, it’s estimated that institutions and individuals hold about $63 trillion in different types of investments. The lion’s share of around $60 trillion is invested in equities (also known as stocks and shares) and fixed-income securities (mainly bonds). The remaining $3 trillion or so (about 5% of the total) takes a variety of forms: hedge funds, private equity, real estate, commodities, venture capital, gold . . . even wine and classic cars. The risks and returns of the many different options vary immensely. At one end of the scale, we know that bank certificates of deposit have almost no risk attached. Conversely, the returns are small.

At the other extreme, venture capital gains can be enormous, but so is the risk of losing money (in the USA, for example, venture capital returns were 37% in 1998 and 225% in 1999, the two best years, but -41% in 2001 and -29% in 2002, the two worst). Venture capital and many other unusual investments are not for the average investor, let alone Georgios, as they can destroy wealth in record time. So let’s confine our attention for now to equities, fixed-income securities, and gold (we’ll return to the others in the next chapter). After all, we have much more historical data for these types of investments and, as we’ve seen, they represent about 95% of the global total.

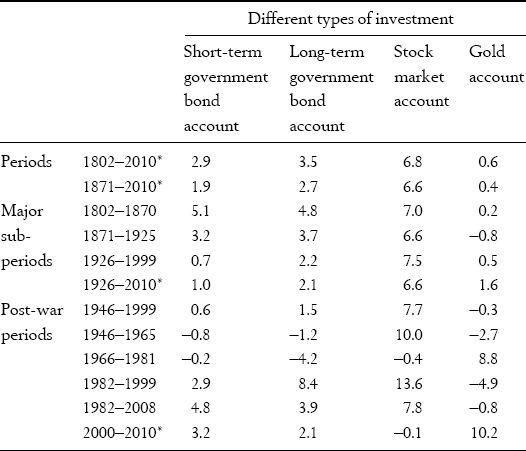

Based on the highly respected work by J. J. Siegel, Stocks for the Long Run12 (and updating his figures with some data of our own), let’s step into a time taxi and go back to the America of 1802. That nasty business with the British finished about twenty years ago and life is comparatively stable again. While we’re waiting for President Thomas Jefferson to buy Louisiana from Napoleon (next year), let’s invest $40,000 dollars by putting $10,000 into each of four different types of investments: gold, short-term government bonds, long-term government bonds, and equities. Moreover, we’ll spread our investment across the entire market for the bonds and shares. Having instructed our broker to reinvest any dividends each year, we get back into the time taxi and whiz forward to 2006. Adjusting for inflation, we discover that the real values of our four different investments are now as shown in table 5.

The differences are absolutely enormous. And the equities win hands down in the long run. But, as the economist John Maynard Keynes once put it, “In the long run we are all dead.” We need to define some more life-sized long runs. So now let’s imagine that the time-taxi driver uses his knowledge of the financial markets to diversify into different kinds of historical investment products. Again based on Siegel’s book, these are the annual interest rates that he can offer you for various periods in US history and our four different types of investments (again adjusting for inflation). Table 6 summarizes these findings.

Table 5 Growth of $10,000 investment from 1802 to 2006

$8,390,179,500 |

(yes this is correct, close to $8.4 billion) for the equities |

$10,888,350 |

for the long-term government bonds |

$3,651,360 |

for the short-term government bonds |

$27,800 |

for the gold. |

Table 6 Tardisbank annual interest rates

* Updated by the authors, March 2010

Note that, in order to get these annual rates of return, you have to put your money in at the beginning of each period and keep it there until the end of the period, reinvesting all your dividends or interest along the way. That’s because – historically – we know that prices of shares, bonds, and gold varied greatly across these periods – and prices may even have fallen steadily for quite some time (something Georgios found to his great cost in the gold market between 1978 and 1999).

The most obvious conclusion is that the time-taxi driver won’t get many takers for the bond and gold accounts at any time period. It may also come as a bit of shock that the difference of rates of return across the 1802 to 2010 period between the stock market and long-term government bonds is so small. Of course, 6.8% is better than 3.5% – but it’s less than double. Remembering our investment of $10,000, can that really make a difference of over $8 billion in returns? The answer is that, compounded over a very long period of time, it really can make that much difference – a lesson to all would-be investors.

As far as the stock market accounts go, it’s clear that there won’t be many customers for the 1966–1981 account and plenty for 1982–1999. But it’s also striking how consistent the rates of return are for the stock market account across the longer periods of time. In fact, it’s not too far from 6.8% (the rate for 1802 to 2010) in all but the shorter post-war investment periods, suggesting that you can probably extrapolate this kind of long-term growth into the future. This is very different from the situation for government bonds, where the lack of consistency suggests that similar long-term predictions aren’t possible.

What you can’t extrapolate – or even see – from table 6 is the fact that the variability of the rates of return from the stock market is also surprisingly consistent across time. In conclusion, short-term investments in the stock exchange are risky, but the longer the term, the better and the less risky the bet.

Back in 1970s Greece, however, Georgios is wearing flares and doesn’t have this information. Nor, to be fair, does he have the same range of investment options as his American cousin George, whose lapels are even bigger than Georgios’s. But a lot of other countries do have stock markets like the USA. Let’s take a look at how they measure up.

The information in table 7 is taken from another highly respected book, Triumph of the Optimists, written by three professors at the London Business School.13 The statistical wizardry and dates used are different from Siegel’s, so the real average return on the USA stock market is 6.3% this time. But the overall message is the same: in the long term equities produce good returns. Clearly, this is much less true in some countries than others, but the average return for all sixteen countries at 5.4% still represents a nice nest egg if you’re prepared to wait 101 years for it to hatch.

Table 7 Percentage annual returns of stock markets by country (1900–2001)

Country |

Percentage annual return of stock market |

Australia |

7.4 |

Sweden |

7.3 |

South Africa |

6.7 |

USA |

6.3 |

Canada |

5.9 |

UK |

5.2 |

Netherlands |

5.0 |

Denmark |

4.6 |

Ireland |

4.3 |

Japan |

4.1 |

Switzerland |

4.1 |

Spain |

3.2 |

France |

3.1 |

Germany |

2.8 |

Italy |

2.1 |

Belgium |

1.8 |

World* |

5.4 |

* The world index is composed of the above sixteen countries, with each country weighted by its starting year market capitalization or GDP.

In other words, if we were to perform our time-travel trick again and rewind to the year 1900 to invest $10,000 in various countries, we’d have the following amounts by 2001.

• $60,610 in Belgium

• $578,790 in Japan

• $4,784,760 in the USA

• $13,534,190 in Australia

• $2,027,220 if we’d invested the original amount across all sixteen countries.

The difference in returns is immense, when compounded over a century plus one year.

The generation of wealth is particularly evident if we return to focus on the USA again. This focus will also enable us to be a bit more realistic. Time travel and long periods of investment are good for illustrative purposes, but they’re simply not possible. For most investors, after all, the long term is a maximum of two or three decades, not a century or more. And investments are made not in the market averages of all stocks traded, but in much smaller portfolios. So, let’s look at the values of the Dow Jones Industrial Average index (which is based on thirty leading companies) since January 1920, as shown in figure 4.

Figure 4 Actual Dow Jones Industrial Average, January 1920 to January 2010

Figure 4 shows the history of a nation in shorthand. In the long term, it’s the story of a vibrant economy and steady growth from 1920 to 2007. But, as well as the broad sweep of history represented by the straight line, we can trace the jagged edges of despair and hope across nearly a century. Note, incidentally, that we have represented the DJIA index on the vertical axis by an exponential scale. This means that the upward trend of the straight line is really increasing at a fast rate.

We’ve highlighted four particular periods.

The first period shows a huge drop in the value of the thirty companies’ shares, then a partial recovery followed by another fall, between September 1929 and April 1942. You can see quite clearly the frenzied selling of shares in the Wall Street Crash, followed by the further decline of the Great Depression. These dark economic times continued through most of the 1930s and things only started to look up again just after the US entered the Second World War at the end of 1941. It took until October 1954 for the DJIA to regain the values of September 1929 – a period of twenty-five years and one month.

The second period runs from January 1966 to October 1982, sixteen years and nine months, during which the value of the DJIA fluctuated and eventually returned to its original value. Economically, this was a highly unusual era of high inflation and zero growth (so-called “stagflation”), low corporate profits, and little productivity growth. Historically, these are also up-and-down years, involving a space race, an oil crisis, and a war in the Far East.

The third period is one of extraordinary growth in DJIA values, starting at the beginning of the 1980s and ending with the bursting of the dotcom bubble at the beginning of 2000, almost two full decades. It’s an era of technological explosion and strong economic growth.

Across these four periods it’s almost as if someone has plotted a family saga, ripe for a blockbuster novel or TV mini-series. After the first part full of grimy faces and soup kitchens, there’s an episode of comfortable middle-class stability, with disturbing yet distant world events played out on a brand-new television set in the corner of the sitting room. Finally, a generation which starts out believing lunch is for wimps comes round to contemplating a distressed future with few opportunities and jobs as the world economy faces its worst recession since the 1930s.

However, regardless of the personal dramas sketched out by the figures, these very different eras weren’t selected for their TV potential. They’re for investment purposes only and show four periods of decline, zero increase, strong growth, and euphoria as well as distress. Our aim is to demonstrate that the “short term” can last more than two full decades in some cases. For example, investors who bought DJIA equities at the beginning of 1966 would have to wait until the end of 1982 to start to see any gains at all (and that’s before inflation is taken into account). Those who bought in September 1929 were even unluckier. During the next twelve years and seven months, they’d be losing money at the rate of 9.9% a year. They’d need to wait over twenty-five years just to get their money back – and by then everyday goods would cost much more, so they’d still be losing out. Conversely, what if you were one of the lucky ones? If you’d bought in April 1980 and sold at the close of the millennium, your investment would have grown at a rate of 14.5% a year. You certainly wouldn’t be complaining. But then if you had left your money in the market and sold in March 2009 you would have lost most of your gains.

To cut a long and complicated story short, returns over shorter time spans can be vastly different from the long-term average. Sometimes that means huge losses on the stock market, sometimes huge gains. Quite apart from the periods of decades and centuries that we’ve just looked at in detail, sometimes there are clusters of months or even days where billions of dollars are lost or gained. For instance, if you’d invested $10,000 in the DJIA in December 1972, you’d have less than $5,900 to show for it twenty-five months later. But if you’d bought in December 1994 and kept your shares for the same period of twenty-five months, you’d be looking at a tidy sum of over $17,600. (Note that these figures aren’t strictly comparable with our $10,000-dollar investments earlier in the chapter, as we’re not re-investing dividends here. In fact, this would only exacerbate the differences between the gains and losses across these periods.)

“Market timing” is clearly critical to short-term success. However, as we saw at the beginning of this chapter, no one knows what the market will do in the short term. They don’t even know when prolonged periods of decline, zero growth, and or strong increase will occur. The uncertainty for investors is huge. And, for certain kinds of stocks, the uncertainty can be even greater . . .

The companies included in the DJIA are thirty of the biggest, most seasoned blue chips, with established competitive advantages and experienced managers. If we see such large variations in the value of the DJIA, what on earth happens to the price of shares in high-tech companies, such as many of those listed on the NASDAQ exchange? Unsurprisingly, the answer is that they vary much more. Figure 5 compares the value of $10,000 dollars-worth of DJIA stocks and the same amount invested in companies listed on the NASDAQ exchange between June 1997 and March 2003.14 To simplify comparisons, we represent the two indexes by the same scale such that both have a value of 100 at the beginning of the period (June 10, 1997).

Figure 5 DJIA and NASDAQ, June 1997 to March 2003

Invest in the NASDAQ on June 10, 1997, sell on March 10, 2000, and you’ve made a fortune. But invest on March 10, 2000, sell exactly three years later and you’re ruined. Meanwhile, the corresponding losses and gains from betting on the DJIA are much smaller. True, the period we chose to illustrate is an extreme case, but it only exaggerates the general rule. And that rule is as follows: the greater fluctuations of the NASDAQ represent greater opportunities, but also greater risks for the investor. Price fluctuations are a double-edged sword.

The NASDAQ “composite” index covers 3,200 individual stocks. Other well-known indexes track the performances of varying numbers of companies. The DJIA is unusual in including just thirty, but – as we mentioned earlier – these are very large, established companies with proven track records. The names – S&P 500, Russell 2000, and the FTSE 100 – speak for themselves. If you invest in a fund that tracks one of these well-known indexes, your money will grow (and shrink) with the index, as reported in the financial pages each day. Similarly, if you pick a number of shares at random from a given index, your investment stands a good chance of reflecting the performance of the index as a whole.

So what happens if you invest in only one company? The answer is simple. Returns are likely to differ significantly from the market average. Figure 6 compares the value of $10,000 invested in the NASDAQ (as before) with the share price for just one NASDAQ company, Amazon, between June 10, 1997 and March 10, 2003 (as before). This time, it’s the NASDAQ curve that looks flat, because the values on the vertical axis are much bigger than last time. Of course, we picked Amazon, because it’s another extreme example. But it certainly illustrates the potential for volatility in individual stocks compared to the fluctuations of a composite which includes several thousands of stocks.

Figure 6 NASDAQ and Amazon, June 1997 to March 2003

This time round, your $10,000 dollars invested in Amazon on June 10, 1997, will be worth close to $660,500 on April 23, 1999. The value of your investment will drop to a little more than $270,000 by October 9 (a fall of nearly 60% in less than six months). But no need to worry for long. Two weeks before Christmas 1999 it will shoot up to $670,500, higher than ever. Celebrations are premature though. By September 28, 2001, your investment will be back down to less than $30,800 in value. But stay optimistic and keep those shares to the end (March 10, 2003) and they’ll be worth over $270,000 again. It’s a shame you didn’t sell just before the millennium celebrations, of course, but you can take heart from the fact that your return is equivalent to that of putting your money in a savings account with an annual interest rate of 64% for nearly six years! That’s got to do your personal Fortune some good, even if it was an emotional and financial roller-coaster along the way.

The influential Canadian-American economist John Kenneth Galbraith once said: “When it comes to the stock market, there are two kinds of investors. Those who don’t know where the market is going and those who don’t know that they don’t know where the market is going.” He was right – at least in the case of those who are out to make a fast buck. There is no evidence at all that anyone can consistently predict turning points and short-term trends. Surprises – both good and bad – occur at a strikingly high rate, as we saw at the beginning of this chapter. On the other hand, it does seem possible to predict long-term trends in the stock market. But when we say “long,” we really mean it. It’s all too easy to get distracted by the “noise” of an Amazon stock and miss the overall pattern (or lack of it) in the NASDAQ or Dow Jones.

We don’t suppose that you’re listening to us. Instead, you’re probably hearing the background chatter of money. Our experience tells us that one strategy followed by nearly all investors is to continue desperately looking for ways to predict the market. As an intellectual exercise this is laudable. If you’re an investor of other people’s money it’s even understandable. Yet, if your own personal Fortune is at stake, we advise you to be more pragmatic. This, as we show in the next chapter, involves forgoing all illusions of control, not succumbing to greed and adopting realistic investment goals. Filter out the background chatter, and you might just hear the beautiful music made by thousands of investment opportunities. To dance to this music is to accept that you are dancing with chance.