Ocean navigation and communication systems have been revolutionised in recent years and, increasingly, there is a cross-over of use between the systems. The Global Positioning System (GPS) is now familiar to most people as a navigational tool and it is very rare to find an ocean-going vessel that does not carry one. Linked to DSC it becomes a vital component of safety communications. Satellite telephones, more advanced HF radios and the internet mean that phone calls, e-mails and downloads at anchor or even mid-ocean are increasingly commonplace. These advanced communication systems allow access to pilotage, tidal and weather data to aid navigation. Electronic charts have become more widely available and are extremely popular because of the ability to link onboard systems and overlay information.

The benefits of such modern electronics are clear, but it remains extremely unwise to be entirely reliant upon them. Batteries may die, electrical or electronic circuits may succumb to the marine environment and fail. Several yachts are struck by lightning every year, and it is not uncommon to lose all your electrics and electronics in such a strike. So there remains a need for old-fashioned, seamanlike commonsense when it comes to navigation. Enjoy all the latest technology as much as you want to or can afford, but always carry sufficient back-up systems to enable you to make safe landfall if your main electronics fail.

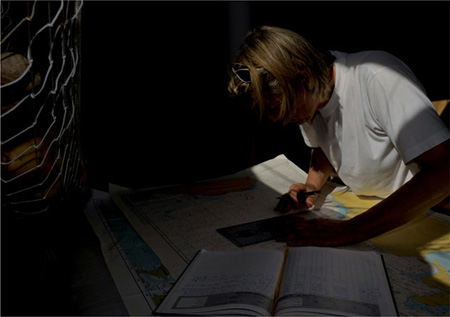

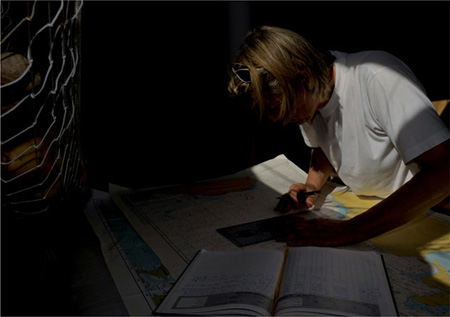

Maintenance of a ship’s log is an internationally recognised legal requirement. Even if you keep an electronic log, it is still a good idea to record the daily position and other basic information in a hand-written copy. This should be a bound notebook, to protect you from any accusations of inserting or removing pages in creation of ‘a story’. Customs and immigration officials may ask to see the log for reasons such as timings of entry into port or a record of ports previously visited. The log is also a place for recording other observations such as whale sightings, and could be used to record parameters such as sea temperature (see Chapter 8).

It is assumed that anyone planning to set off across the Atlantic has a reasonable level of navigational knowledge and experience. If you lack confidence, there are a multitude of courses available at all levels, both theoretical and practical, and it never hurts to refresh your understanding.

Chart accuracy

Very few cruising sailors keep their charts and pilot books corrected up-to-date. Once you are away from home waters it becomes difficult to access the information regularly. New editions of charts use WGS 84 which is the same as the GPS system. If a different datum is used, a correction may be given. Worldwide, even apparently modern charts, both paper and electronic, are quite often based on ancient surveys. These surveys were remarkably accurate, but there were sometimes errors, more usually in longitude than in latitude, and these can be as much as half a mile. In other words, the GPS position of a feature or even a whole island may not be the same as its charted position (paper or electronic). With this in mind it is prudent to be cautious when making a new landfall at night or in poor visibility. Until you have visual evidence that supports the charted information it is wise to assume that some differences are possible. Also never assume that buoyage will be exactly as charted or described. For example, on the coast of West Africa it is common for buoys to remain as charted but to be unlit. Elsewhere, local buoyage may change overnight.

This catamaran relied too heavily on the GPS on approach to Tortuga. Photo: Richard Woods

Gnomonic charts and Great Circle sailing

The shortest distance between two points on a globe is a Great Circle. A rhumb line, the straight line on a Mercator chart, goes by a longer route. In practical terms, the difference is negligible except in high latitudes. For routes between the northern part of the United States and northern Europe, the saving of distance made by keeping to a Great Circle route is likely to be considerable. GPS receivers usually display course to the destination waypoint as a Great Circle bearing, although on many the rhumb line option can be selected.

GPS, chartplotter or sextant

There are now very few cruising yachts which rely entirely on traditional means of navigation. For most cruisers the GPS, often in the form of a chartplotter, is the primary navigational tool. Some choose also to carry a sextant, either simply as a back up, or to learn, or practise the ancient art. The downside of this is that you also need to carry all the relevant tables which add up to several reference volumes. If you have never or only rarely used a sextant it is questionable that you would then use it to any good effect in an emergency situation. Nevertheless, just knowing how to establish ship’s latitude would greatly assist in emergency navigation if all electronics were destroyed by lightning. Increasing numbers of cruisers carry one or two GPS or chart plotters and have a hand-held GPS for emergency situations. If a thunder storm approaches you can put the hand-held GPS into your oven to protect it (see lightning section in Chapter 7). Then even after complete electrical failure you should still be able to switch the GPS on once or twice a day to get a position reading. A hand-held GPS can also be useful for surveying a new anchorage from the dinghy.

GPSs are available in a range of complexities. How you use your GPS will determine what functions you feel you need. If you are a gadget person you probably spend many happy hours pre-programming your machine and monitor the readouts continuously. Other cruisers may prefer to keep things simple and monitor only distance and bearing to a single waypoint, or even just record a current position at regular intervals. In mid-ocean this is really all you need. Your log and compass complete the picture. However in coastal situations, and particularly in tides or currents, the SOG (speed over the ground) and COG (course over the ground), seen in relation to a bearing to a waypoint, can be an extremely useful and immediate tool for assessing the strength and direction of water flow. This can help to prevent you from being set down onto danger, particularly at night or in poor visibility.

Waypoints should always be used with caution. Always check waypoints on a chart before programming them in but, above all, check that you, your charts and your GPS(s) are all working to the same datum. Even then remember that, particularly at night or in poor visibility, if you have created or confirmed a waypoint from a chart, there may nevertheless be a significant difference between the charted and actual positions. Don’t be lured into blindly following the course laid out on the screen. Use your common sense and make the best use of your GPS as only one of the navigational tools that you have at your disposal and confirm its information by visual or radar observation.

Those were the days! But take the opportunity on passage to learn to use the sextant – you may be glad of the knowledge one day. Photo: Lou Newman

Echosounder

Even an ocean-going yacht spends most of its time within soundings, often in unfamiliar waters, and a reliable echosounder is a top priority. A lead line can be tricky to use, particularly for shorthanded crew, so it is worth carrying a spare echosounder. Its transducer can be fitted before departure and the set itself stowed away in a protective environment.

Radar

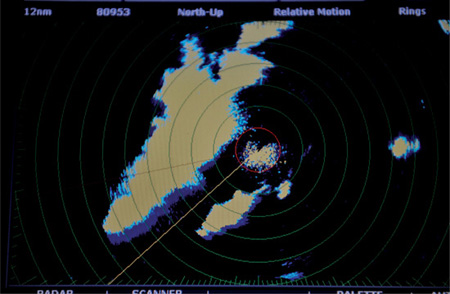

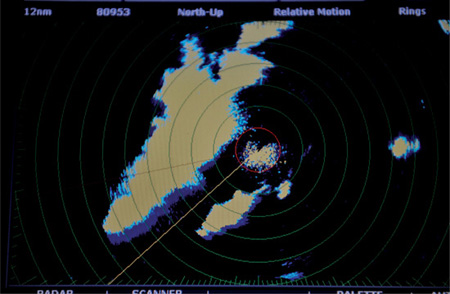

Radar has obvious uses as an aid to collision avoidance in poor visibility or at night and it also helps with spotting approaching squalls and thunderstorms. It is a useful tool when making landfall if used in conjuction with other information and instruments. In the north Atlantic, radar is a real bonus for boats planning to cruise in Maine and Nova Scotia or on the north European coast, particularly in the western approaches to the English Channel, where fog is common. It is an essential tool if you are considering the northern or ‘Viking’ routes. However, sailors should be aware that, under the Collision Regulations, vessels fitted with radar are obliged to use it, and use it properly, when visibility is poor. Failure to do so, resulting in an accident, might result in an insurance claim being rejected. Radar is not a substitute for maintaining a visual watch.

Radar can be useful for tracking squalls. Photo: Mike Robinson

AIS

The Automatic Identification System (AIS) is a short range, electronic, vessel tracking system. Class A systems are now required to be fitted to commercial vessels. They integrate AIS transceivers with other components to allow shore stations or other vessels to track nearby ships. Information transmitted on AIS includes the vessel’s unique identification number, position, course and speed. There are a variety of ways in which the information can be displayed. Class B AIS systems are becoming increasingly popular watch keeping components on pleasure vessels such as cruising yachts. AIS signals are transmitted via VHF and the most simple ‘receive only’ AIS sets use the yacht’s normal VHF aerial to receive Class A and B signals. These sets use relatively little power. Transceivers can share the yacht’s VHF aerial but must also be connected to a dedicated GPS aerial. Transceivers are more power hungry than ‘receive only’ sets and they have to be registered in a similar way to VHF and EPIRBs. If you have a Class B transceiver on board, do not assume that other vessels will ‘see’ you. Ships and shore stations may choose to switch off any Class B signals if their screens become cluttered.

Eyeball navigation

Eyeball navigation is the name commonly given to judging depths by eye around shallow coral-strewn waters. For the first timer, the technique can seem daunting, but some of the most magical anchorages are accessed this way so it is worth getting to grips with. The trick is to get one of the crew as high as possible above the deck so they are looking down into the water for a good distance all around the boat. Polaroid sunglasses help to reduce the glare and improve colour differentiation for this look-out crew member. In areas where you know there will be shoals and coral it is important to make your approach with the sun high in the sky and, preferably, behind you. Once the angle of the sun is relatively low, and particularly if it is ahead of you, the sunlight reflecting off the water becomes a barrier to seeing down through the surface.

Shallow water over clear sand looks turquoise. Pale turquoise becomes darker as the depth increases and becomes a much darker blue in a deep channel. Coral heads generally appear as a browny-green colour. Confusion can sometimes arise where a sandy bottom has patches of sea grass. From a distance these can look a similar colour to coral, but on closer approach, the difference is more obvious.

Local cruising guides for coral waters usually have helpful advice about navigation techniques and passage timings.

It is sensible to maintain a paper log. Plotting a daily position whilst crossing the Atlantic is usually a morale-boosting ritual. Photo: Mike Robinson

Integrated systems

Many boats are now fitted with fully-integrated, linked systems. A major drawback of this would be if the failure of a single component affected the function of the whole system. For example, should an electronic wind direction indicator fail on passage it is unlikely to be more than an inconvenience. But if that failure led to the loss of other instrumentation, the situation might be more serious. If you do have an integrated system it is a good idea to keep separate a basic log, GPS and autopilot that are independent of other instruments and can be used as back up.

Laptops

Laptop computers and printers are now commonplace aboard voyaging yachts. Appropriate software enables them to fulfil a variety of useful roles including navigation, weather monitoring, communication and record keeping. They have also helped to revolutionise the distance learning possibilities for cruising families as well as onboard entertainment. Marinised computer units are now available, but most onboard computers are vulnerable to the effects of life afloat. Secure, dry stowage should be a priority. Carry plenty of memory sticks or similar storage devices and always back up anything of importance. You can run a laptop from a 12V cigar socket at the chart table using a laptop car power supply (which acts as a DC/DC converter to take the 12V up to a variety of voltages suitable for many laptops). This is more efficient than going from 12V to 240V then down via a transformer back to the laptop voltage. The saving is several amps per hour.

In recent years, communication at sea has benefitted from an ever-increasing, ever-accelerating tidal wave of technological advances. For the uninitiated, this whole topic can appear to be a mind boggling jumble of acronyms, frequencies and other technical jargon. The aim of this section is to try to introduce and explain various components, without getting too caught up with technical details. Anyone who wishes to immerse themselves more fully will find the various links helpful.

It is important that both yacht and crew carry all the relevant certificates and licenses appropriate to the communication systems on board. Links to courses are given in each section.

A thorough overview of the subject, including some product reviews, is given in Ship and Boat International Nov/Dec 2008 – Sea changes in maritime communication by George Marsh.

VHF

VHF (Very High Frequency) radio is the most common form of onboard communication. It is generally operable to a range of up to 50 miles, depending on various factors. It is really limited to line of sight. It is now universally recommended that a yacht will carry a main VHF with DSC capability. An operating certificate is required. All VHF emergency traffic is conducted on channel 70 DSC off Europe and North America.

Cruising yachts routinely use their VHF to contact each other on passage or in port and also to alert commercial vessels to their position. Communications with harbour authorities are also often dependent on VHF. A waterproofed, handheld VHF set is very useful for crew going ashore in the dinghy, and is an extremely valuable component of an emergency grab bag. Floating, submersible units are now available.

VHF channels are preset and operators do not themselves tune to the frequencies. Internationally, VHF channels are duplex, with transmission and reception on different frequencies on the same channel. In the United States, some channels are simplex, with both transmission and reception taking place on the same international ship transmitting frequency. Modern VHF sets now all have a facility for selecting either the international or US set of frequencies. US frequencies allow reception of the continuous, dedicated US VHF weather transmissions.

UK VHF training courses are run by the RYA.

DSC

Digital Selective Calling (DSC) is one of the most important parts of GMDSS. DSC is a digital dialling system which can carry information such as a vessel’s identity, and the nature of the call. If there is GPS input to the radio, a position will also be transmitted. In a distress situation, all necessary information can be sent automatically at the touch of a single button. The entire message is transmitted in one quick burst, thus reducing the demand time on the calling channel. The digital calling information is transmitted on specially designated channels. VHF Channel 70 is dedicated for DSC use and must not be used for anything else.

GMDSS

The Global Maritime Distress and Safety System (GMDSS) is a fully automated system which forms a part of the Safety Of Life At Sea (SOLAS) Convention. All ocean-going cargo and passenger ships of 300 tonnes gross or more, engaged on international voyages are required to be GMDSS-equipped. SOLAS is an international treaty responsible for ensuring the safety of merchant ships but is also relevant and applicable to cruising yachts. GMDSS incorporates various communications technologies including NAVTEX, DSC, INMARSAT and EPIRB (see following sections). GMDSS is designed to optimise rapid and accurate communications via a shore-based Rescue Coordination Centre (RCC) in the event of a vessel in distress, such that a co-ordinated Search and Rescue (SAR) operation can be implemented with the minimum delay. The system alerts vessels to any safety or distress information and allows for subsequent communications. It also provides for the promulgation of Maritime Safety Information (MSI) such as navigational and meteorological warnings and forecasts and other urgent safety information. GMDSS weather information is produced by meteorologists who have interpreted the raw data. It is useful in addition to alternative sources such as GRIB files (see following section) which are generated exclusively via computer models. Under GMDSS, all vessels are allocated a Maritime Mobile Service Identity (MMSI), which is a unique nine digit code. While GMDSS now provides a safety net that may increase the chances of survival in a marine disaster, it should always be treated as a last resort (see Chapter 7).

NAVTEX

NAVTEX (Navigational Telex) is part of GMDSS and is an international system for the broadcast and automatic reception of maritime safety information. NAVTEX provides continuous weather and navigation warnings and frequent weather forecasts by means of narrow-band telegraphy through automatic printouts from a dedicated receiver. It is included as an element of GMDSS. NAVTEX transmissions are sent via a single frequency from local stations situated worldwide. The power of each transmission is regulated so as to avoid the possibility of interference between transmitters. NAVTEX is broadcast in English, and often in the local language too. The receivers are relatively cheap and easy to install; they can have either a direct readout screen or produce the same information on a paper roll. NAVTEX is the most economical means – in terms of cost and power requirements – of receiving continual weather information. The only disadvantage is the limitation of range to about 300 miles from the stations. The European and West African coasts are covered in Regions I and II. The western area of the North Atlantic is Region IV.

Marine SSB and amateur (ham) radio

Single Side Band (SSB) radio, operating in the Medium Frequency/High Frequency (MF/HF) bands, remains a mainstay on board many cruising yachts and is generally referred to as SSB or HF radio. SSB radios are available as two separate types – either marine SSB or amateur (ham) radio. Marine SSB radios must be ‘Type Approved’ – they use simplex or duplex frequencies within specified marine bands. Ham radios operate throughout the amateur bands but are restricted from use on marine frequencies. It is common practice amongst cruising yachts to ‘open up’ an amateur radio to marine frequencies, but there are licence implications (see modifications website below). Although they are not yet necessarily ‘Type Approved’, it is now also possible to program the latest marine SSBs into amateur bands, but only with proof of an amateur licence. To fully access all the potential communication links, rather than simply being a passive listener, you need to fit a transceiver (transmits and receives) rather than just a receiver. Only qualified, licensed amateurs (hams) may transmit on the amateur bands, but anyone may listen. You will be able to find amateur radio courses available locally if you would like to qualify. There is no longer a requirement to use Morse Code.

Installation

HF radios, whether marine or amateur, require proper installation. They are not just a single component but also consist of interconnected components – antenna (aerial), tuner, and modem. They are power hungry when transmitting, and are particularly sensitive to a reduction in input voltage, so heavy supply cables are essential. An insulated shroud or backstay creates the aerial, but providing a good earth for the set and aerial tuning unit is equally important. In a steel yacht, the hull itself will provide an excellent earth, but wooden or glassfibre yachts need an external ground plate below the waterline.

Computer links

It is now common practice to link a laptop computer to an HF radio to send and receive e-mails and to receive GRIB files and other information without online charges, although file size is restricted due to limited data speed. AirMail is a radio mail software program (equivalent to Outlook) for sending and receiving messages via a modem (modulator/demodulator) over HF radio, either via the ham radio system or participating marine and commercial services. Sailmail is a subscriber SSB e-mail system that uses Airmail. The frequencies used are mostly within the marine bands. Winlink is a free communication system, produced by and for licensed radio amateurs, which also uses Airmail.

Safety networks

HF operators can use the Sailmail and Winlink systems to send distress messages, but it is also possible to buy an HF radio with DSC – operation of such a set requires a GMDSS Long Range Certificate.

Communications are changing worldwide. In this San Blas village in the western Caribbean, villagers now have mobile phones.

Photo: Richard Woods

HF radio also gives access to weather voice broadcasts, stations such as the BBC World Service and the French ‘Meteo’, international time signals, and multi-party conversation with other HF operators.

Satellite telephones

Satellite communications are increasingly affordable and available for use on board. They allow you to phone, e-mail and access the internet even in mid-ocean. The latest generation of satellites has opened the door to continuous broadband while at sea. The original Inmarsat systems (International Mobile Satellite Organisation) are still the choice of many ocean sailors and are integrated within GMDSS. Iridium is an increasingly popular alternative which provides the option of a handheld unit which you could take with you into a liferaft. The MailASail website gives a good description of the various satphones available and a comparison table of their characteristics. Make sure that you understand the usage tariffs and take these into account when costing the different systems.

Long range communications – SSB versus satphone

Transatlantic yachts are now commonly fitted either with an SSB radio, a satphone or both. Either system allows voice calls, e-mails and downloads from the internet such as GRIB files. There are pros and cons to each system depending on how much they are used. With the reduced cost of satellite phones, SSB may appear to be an expensive alternative, but probably not if you take into account usage costs over a period of time. The flip side of this is that SSBs cost more in amp-hours. SSBs are ‘plumbed in’ to the boat and consist of several separate components, whereas some types of satphone are single units which could be taken into a liferaft. You need the appropriate training and licences for an SSB, which is not always the case with a satphone. If you want to be able to participate in daily radio nets with other yachts you will need an SSB – a satphone will only allow one-to-one calling. But file downloads are more restricted with an SSB. The various technologies are progressing at such a fast rate that any detailed discussion quickly becomes out of date. If you are considering the advantages and disadvantages of various onboard long range communications it is worth investigating the current options. Whichever system you choose, it is recommended that you use compression software.

A good-quality steering compass (corrected for deviation before leaving home waters)

A good-quality steering compass (corrected for deviation before leaving home waters) A hand-bearing compass

A hand-bearing compass Aneroid barometer

Aneroid barometer Thermometer (Air and water temperatures can be useful, for example at the edges of the Gulf Stream.)

Thermometer (Air and water temperatures can be useful, for example at the edges of the Gulf Stream.) Relevant charts

Relevant charts Tidal information (electronic and/or paper tables)

Tidal information (electronic and/or paper tables) GPS (connected to 12V system or battery powered hand-held, plus a hand-held back up)

GPS (connected to 12V system or battery powered hand-held, plus a hand-held back up) Sextant plus all supporting tables and texts if desired (see discussion below)

Sextant plus all supporting tables and texts if desired (see discussion below) Log plus spare impeller or spare towing log (or piece of degradable paper thrown overboard at the bow and timed to the stern!)

Log plus spare impeller or spare towing log (or piece of degradable paper thrown overboard at the bow and timed to the stern!) Echosounder (plus spare or lead line)

Echosounder (plus spare or lead line) Masthead wind instruments (can be damaged by visiting birds) are helpful for optimising rig and course steered but should be interpreted sensibly – some crew are liable to become overly anxious when masthead windspeed figures rise, but such figures do not necessarily give a balanced picture of the prevailing conditions)

Masthead wind instruments (can be damaged by visiting birds) are helpful for optimising rig and course steered but should be interpreted sensibly – some crew are liable to become overly anxious when masthead windspeed figures rise, but such figures do not necessarily give a balanced picture of the prevailing conditions) A good pair of polaroid sunglasses and a shroud ladder or mast steps (to help with eyeball navigation in coral waters – see page 49)

A good pair of polaroid sunglasses and a shroud ladder or mast steps (to help with eyeball navigation in coral waters – see page 49) Binoculars

Binoculars