North of 50°N, yachts transiting eastwards or westwards between Europe and North America face the likelihood of encountering severe weather. In the past these waters have been the domain of transatlantic races and a handful of experienced and hardy cruisers. But there appears to be an increasing interest in northern passages and landfalls, so it seems pertinent to outline some of the possibilities which lie therein. You do not need a steel ice-breaker to venture into these waters, indeed Contessa 32s appear well-suited to the task. But you do need to give due consideration to all the potential hazards and to the advice of those who have ventured before you. Be well prepared for storms and cold.

Ice at sea is a significant risk for any yacht, but on most routes you may only encounter the occasional isolated iceberg. A good look-out is essential, and given the prevalence of fog, radar is strongly recommended.

Note that magnetic variation differs as you cross the Atlantic, rising to more than 20° of westerly variation near 50°W. The amount of variation fluctuates slowly, rates varying from place to place. Ocean passage charts show isogonic lines, linking places with equal variation, and also give details of annual changes.

Plan 81 Ports and passage distances in the higher latitudes of the North Atlantic

The extent of sea ice cover varies within and between seasons and any information about ice limits can quickly become out-of-date, particularly in strong winds. There are various possible sources of information, all of which should be treated with due caution. The Danish Meteorological Institute publishes ice charts for Greenland on their website (see below); these are also broadcast from Skamlebaek as Radio-fax. The information is provided by Iscentralen (Ice Central), the office based at Narsarssuaq in south-west Greenland, who also provide an ice advisory service by telephone or radio. The area west of 54°W is covered by the Canadian Ice Service.

The US NOAA National Ice Centre website (see below) carries ice charts for the Arctic and Greenland. See the national snow and ice data centre website given below.

The US Coast Guard, International Ice Patrol monitors iceberg danger near the Grand Banks of Newfoundland and provides the limits of all known ice to the maritime community. The IIP does this by sighting icebergs (primarily through airborne Coast Guard reconnaissance missions), plotting and predicting iceberg drift using a model, and, every 12 hours during the ice season, estimating the ‘limit of all known ice’. This limit, along with a few of the more critical predicted iceberg locations, is broadcast by radio stations and made available on line as an ‘Ice Bulletin’. Twice daily, a radio facsimile chart of the area, depicting the limits of all known ice, is broadcast. The IIP broadcasts its products during the time of year that icebergs threaten shipping. This varies, but usually begins in February and ends in July. Go on their website (see below) and click on ‘Announcement of Services’ for current broadcast times and frequencies. Click on ‘Latest ice Limits’ for current information either as text or in chart format.

The ‘limit of all known ice’ tends to err on the side of caution and encompasses some areas which may have very few icebergs. This report on its own may not necessarily warrant a change of course.

Plan 82 Prevailing winds and currents across the North Atlantic in the higher latitudes during June. Maximum limits of ice and icebergs are shown. Based on information from The Atlantic Pilot Atlas and Arctic Pilot Vol II

The mid-latitudes, as far as this passage is concerned, may be defined as a track passing south of Sable Island and the Newfoundland Grand Banks but well north of the Azores high pressure system. If the yacht is lying west of Cape Cod, the choice is either to sail south of the Nantucket Shoals or transit the Cape Cod Canal and leave from further north.

Fog and ice make radar a priority in these waters. Photo: Mark Hillman

Fog, ice and shipping lanes will influence the course chosen, but an arbitrary waypoint P (40°N 50°W) is a reasonable way to start. Up-to-date weather and ice reports may make it possible to shift this point further north to reduce the distance sailed, but the track may then coincide with the main shipping routes. If ice is reported particularly far south, it may be wise to head further south. From 50°W a Great Circle course can be sailed for most European destinations. Winds will be predominantly westerly, but may veer right around the compass as depressions pass through. West of 30°W, up to one knot of north-easterly current may be experienced, but both the strength and northerly component diminish further east.

From anywhere in the north-eastern United States the Great Circle route to northern Europe runs close past the coast of Nova Scotia (well inside Sable Island) and thence to Cape Race on the southern tip of Newfoundland. This is likely to be a predominantly downwind passage, but there can be a high incidence of fog, and there will also be the weak adverse Labrador Current on this part of the route. St John’s Harbour, 60 miles north of Cape Race, makes a good final port for provisions and stores. From Cape Race or St John’s you can shape a direct Great Circle course. Icebergs and fog are a risk until around 40°W. East of 40°W normal northern Atlantic conditions can be expected with fair winds and current, but there is a good chance of at least one severe gale and correspondingly big seas if crossing this far north.

Prins Christian Sund Icefall. Photo: Mark Hillman

Any passage westward across the Atlantic in the higher latitudes involves a lot of windward sailing, adverse currents, fog, ice and a strong likelihood of encountering frequent gales. Whatever latitude you choose, this passage is, according to one connoisseur, ‘a long thrash to windward with a permanently foul tide’. Winds will mainly have a westerly component, and there is a high probability of heavy weather as Atlantic depressions track across. The northern route is unusual amongst cruisers but common to entrants in various transatlantic races because it offers the potential of a fast passage, but it is likely to be cold and stormy. The accepted wisdom for this crossing is to close-reach on whichever is the making tack towards your objective. A typical point to head for is 55°N 30°W and then on to St John’s, Newfoundland or to Cape Race and beyond. If making for the west coast of Greenland, aim for a point at least 150 miles to the south of Kap Farvel (Cape Farewell) before turning north. A lot of heavy, multi-year, drift ice (storis) is brought down from the Arctic Ocean on the East Greenland Current in a narrow band and is carried around Kap Farvel, often as late as July. This southern point of Greenland is also another ‘Cape of Storms’ because winds are squeezed and accelerated between the Atlantic lows and high pressure over Greenland. Boats have been knocked down as far as 140 miles south of the cape.

Onboard radar is considered essential for the northern route. The combination of drift ice and icebergs, often coupled with fog, as well as heavy shipping on the coasts of north America, mean that without radar, a yacht would need to be fully crewed to maintain a constant watch. And although in the northern summer there is virtually constant daylight, towards the end of the crossing it is likely that nights will get longer and icebergs show no lights! Although it is not certain that all ice will show up on radar, multi-year storis does usually show up and sometimes even low-lying ‘growlers’. Icebergs, being deep-keeled, are carried by the current, whereas bergy bits and growlers tend to be wind driven and therefore lie downwind of icebergs. So by passing to windward of the icebergs, you should also avoid the bergy bits. Another reason for having radar is that without it, even with a GPS, navigation in areas where there are cliffs and craggy islands can be quite stressful in fog. Your instinct may be to get out of the opposing Gulf Stream and into the favourable Labrador Current as soon as the ice situation permits, but this will mean heading into the worst of the fog. Cape Race has a 40 per cent incidence of less than two miles visibility in July.

The route through Prins Christian Sund narrows may be impassable if the ice has not retreated sufficiently. Photo: Mark Hillman

Cruising in the North Atlantic is not the dream of most sailors, whatever their level of experience. However, for some of those who have ventured into these waters, the rewards of sailing north of 60°N surpass all other cruising experiences. A logical path across the top of the Atlantic has been well beaten over the centuries. From the east, the route follows the Norse migrations of the 10th century and before them St Brendan and the Celts. The western end is the domain of the Inuit. Either heading eastwards or westwards across the northern Atlantic, with access to good weather forecasts and ice reports, and with time and prudence on your side, it is possible to experience an enjoyable and memorable cruise. The fact that the Arctic sea ice is reportedly receding year on year may open up some of the previously ice-bound regions to create even more possibilites for the adventurous.

From Norway at the eastern end of the route, the first stepping stone is to Shetland. From Shetland, or from the coast of Scotland, the first step is to Faroe. From Faroe you sail on to Iceland. In fair conditions, each of these passages is only two days sailing and each destination is a new cruising ground. The onward passages between Iceland and Greenland, Greenland and Labrador or Newfoundland are a few days longer, but they are still much shorter passages than direct routes between North America and Europe. On any passage in the high north there is a likelihood of encountering heavy weather, but in June and July the long day length is a friend. If you are lucky you will sometimes be able to make use of the easterly winds that blow over the top edge of low pressure systems passing to the south.

Boats passing round the north of Scotland, should have no problems provided they are well clear of Rockall (57°37´N 13°41´W). The St Kilda Island group and the Flannan Islands, 40 miles and 20 miles off the west coast of the Outer Hebrides, should not pose a threat, but Sula Sgeir (59°06´N 6°11´W) and North Rona (59°08´N 5°50´W) could be close to the route and are hazards to be avoided in bad weather. Both are lit.

The passage through the Pentland Firth, between the north Scottish coast and the Orkney islands, should not be attempted in strong winds or poor visibility. Coming from the north-west, shelter can be sought in the lee of Lewis by passing round the Butt of Lewis to Stornoway on the east side. Stornoway is an official Port of Entry with good facilities for yachts. Under no circumstances should the Sounds of Harris or Barra be attempted by a stranger in other than ideal conditions. If approaching the southern end of the islands, pass at least three miles clear of Barra Head to avoid the strong tidal stream and heavy overfalls. The best haven in the south is Castlebay, Barra. When anchoring in Scottish waters, beware of kelp; a heavy anchor should be used.

The Faroe Islands are an archipelago of 18 islands lying close together on the 62nd parallel. They are carpeted with green, though mostly denuded of trees, and are characterised by their steep cliffs separated by deep but narrow channels. These channels force the tidal flow into potent rips and races, causing widespread overfalls around the islands. The capital of Faroe is Tórshavn on Streymoy, where visiting yachts will find all the usual facilities of a large harbour town plus ferry links and access to international flights. However, the strong tidal streams may make Tórshavn a problematic point of arrival. With this in mind, many yachts make landfall in Trongisvágsfjørður on the east coast of Suðuroy. The approach is straightforward and, if the wind is not funnelling down the fjord, an initial safe anchorage can be found in 5-8m (16–26ft) sand on the west side of Tjaldavíkshólmur. Tvøroyri harbour is a Port of Entry; it is completely secure and has good facilities.

When sailing from the Faroes to Iceland you should consider whether or not you plan to cruise around the coast. The south-east coast is low-lying, shallow and dangerous, with no harbour or shelter at all for 150 miles between Hornafjörður and Vestmannaeyjar (note that Hornafjörður/Höfn is not a safe, first port of call due to difficult navigation on account of the strong tidal streams and continually shifting sandbanks). If your cruising time is restricted, Vestmannaeyjar harbour on the north side of Heimaey in the Vestmann Islands (on the south-west corner of Iceland) is an excellent point of arrival. From there it is straight-forward to sail to the capital, Reykjavík, and tour the surrounding area. If you are planning a more extensive cruise around Iceland, and are approaching from Faroe, it may make more sense to use Seyðisfjörður on the east coast as a point of arrival. This is a first class harbour and a Port of Entry. Ferries from Europe terminate here and it is possible to enter the harbour under virtually any conditions, even dense fog under radar.

The west coast of Greenland is a cruise in itself. By August, the ice has usually retreated from most of the potential anchorages in the south-west of Greenland, opening up a stunning cruising area. In some years it is possible to enter Prins Christian Sund to the east of Kap Farvel and then sail through the interconnected fjords to emerge on the southwest coast although cruising this route should be considered a bonus. Sailing from St John’s towards Qaqortoq should be possible in July because, to the south of the Davis Strait, the sea is virtually ice-free. But from either direction you should monitor ice reports before planning a landfall at Qaqortoq as the entrance can remain completely blocked by heavy drift ice, known as storis, until late July. Harbours up the west coast may open much earlier; it is wise to keep your plans flexible to allow for ice and weather.

Heading towards Europe from Greenland it is wise to complete the trip by the end of August or mid-September, though boats have done it safely later than this. Erik the Red had his homestead at Brattahlið near Narsarsuaq Airfield, about 30 miles from Qaqortoq.

If you are heading from south-west Greenland westwards, the nearest good harbour in Newfoundland is St Anthony. This is close to the only known Norse settlement in North America at L’Anse aux Meadows and makes an interesting point of arrival, particularly if you are set on completing the Norse Experience. The first survey of the area was by Captain James Cook aboard HMS Grenville in July 1763. Most yachts prefer to head 150 miles further south to St John’s; a major harbour with all facilities and good communications. Vessels should call ‘St John’s Traffic’ on VHF Channel 11 or 14 about two miles from the entrance to obtain clearance for entering and to avoid meeting a large container ship head on in the narrows.

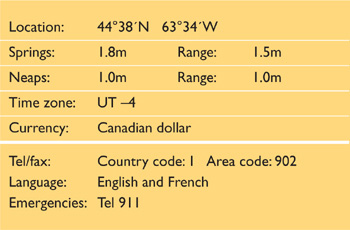

Halifax is the capital of the Canadian province of Nova Scotia. It is a large commercial port and a naval base, and an official Port of Entry. Yachting activity is largely centred in the North West Arm, a long narrow bay branching off just inside the main entrance, and in Bedford Basin north of the city. The city was settled by the British in 1749 and it has been a permanent settlement ever since. It has a rich maritime heritage and several historic sites are worth visiting including the star-shaped Citadel. Pier 21 gives an insight into what it must have been like to arrive here as one of the many thousands of immigrants who came here in the 1900s. Halifax undertook the grisly task of sending ships to recover bodies after the sinking of the Titanic and some of the city’s graveyards are the final resting place of victims of the disaster.

Halifax: the North West Arm with the Royal Nova Scotia Yacht Squadron moorings on the left. Photo: John Gibb.

Sable Island (43°55´N 59°50´W) lies just under 100 miles off the coast of Nova Scotia and should be given a wide berth. With its strong and unpredictable currents and shoal water it is a graveyard for ships. In the southern part of Nova Scotia a strong in-draught has been reported in the vicinity of Cape Sable. Oil rigs may be encountered in the area. Nova Scotia is subject to considerable periods of fog during the summer months, particularly with onshore winds. In poor visibility it is wise to exercise caution when closing the coast.

Plan 83 Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada

The coastline of Nova Scotia is rugged and hilly with many inlets. Off-lying rocks and small islands extend up to five miles from the coast in places. These are usually all well marked, but working lights and fog signals should not be relied upon in poor conditions. If approaching from west of 63°30´W, beware the area of shoal water and isolated rocks off Pennant Point and Sambro Island. In bad weather the sea breaks fiercely.

The final approach to Halifax is between Chebucto Head to the west and Devil’s Island off Hartlen Point to the north-east. Chebucto Head is a 30m (100ft) headland of whitish granite with a light [Fl 20s 49m 14M] shown from a white tower. Devil’s Island light flashes [Fl 10s 16m 13M]. Portuguese Shoal and Rock Head Shoal lie in the approaches and are well buoyed. There are numerous other buoys and leading lights in the final approach. If entering at night, the leading lights at George’s Island and Dartmouth will be useful (but keep a careful watch for shipping). Enter the harbour between Sandwich Point and McNab’s Island. Shipping generally uses one or other of the tracks indicated on the plan, and as there is good water outside the channel, yachts may do better to keep further west. The only possible hazard is a 2.0m (7ft) patch about 0.5 miles south-east of Sandwich Point.

‘Halifax Traffic’ operates a Vessel Traffic Management System for all vessels over 20m (65ft) and will advise smaller craft on the proximity of shipping. It monitors VHF Channel 16 and works on Channels 12 and 14 (Channel 14 for traffic to seaward of Chebucto Head, Channel 12 in the harbour itself). The harbourmaster uses Channel 65A. The Canadian Coast Guard monitors Channel 16, and works on Chanels 26 and 27. In addition, a continuous weather forecast is broadcast on Channel 21B. The Royal Nova Scotia Yacht Squadron and other marinas and yacht clubs use Channel 68.

Fly the Q flag from offshore if arriving from abroad. On arrival call Canadian Customs Control on 1 888 226 7277 (toll free 24hrs), with all yacht and personal details to hand. They will want to know the yacht’s exact location and will then issue a Report Number. Local Customs will then visit the yacht to stamp the passports of non-US or Canadian nationals. All weapons, firearms and alcohol must be declared. There is a total ban on retaining hand guns on board. Restricted goods may be brought into Canada if an appropriate permit, certificate, licence, or other specific required documents have been issued, and if the goods meet certain safety standards. Controlled goods include endangered species of animals and plants and any item made out of them.

Opposite the northeast corner of McNab’s Island:

The Canadian Forces Sailing Association/Shearwater Yacht Club is located on the Dartmouth side of the harbour, tucked behind McNab’s Island and well sheltered from the elements. Marina facilities include showers, laundry and a bar (open Wednesday and Friday evenings, Saturday and Sunday afternoons).

Contact: Box 280, Shearwater, NS, B0J 3A0. Tel: 469 8590

Fax: 469 0639 E-mail: syclub@psphalifax.ns.ca

In the North West Arm:

Royal Nova Scotia Yacht Squadron is located at the entrance to North West Arm in Halifax harbour and is particularly welcoming to visiting yachtsmen. It has a good range of services including a marina and boatyard with haul-out and shore storage up to 20 tons. Fuel dock, pump-out.

Website: www.rnsys.com

Contact: 376 Purcell’s Cove Rd, Halifax, NS B3P 1C7, Canada. Tel: 477 5653 Dockmaster: 477 2595 Fax: 477 2595

E-mail: rnsysboatyard@ns.sympatico.ca

Armdale Yacht Club is at the head of the North West Arm in Halifax harbour at 40 Purcell’s Cove Road, Halifax. This is relatively close to town. There are several large grocery stores within walking distance and a bus service runs into the town. The club welcomes visiting yachts and provides a range of facilities including safe anchorage, moorings and a fully serviced marina with a 20-tonne boat hoist (up to 45ft/14m).

Website: www.armdaleyachtclub.ns.ca

Contact: PO Box 22105, Bayers Road Postal Outlet, 7071

Bayers Road, Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada B3L 4T7.

Tel: 477 4617 Fax: 477 0148

E-mail: office@armdaleyachtclub.ns.ca

There are two yacht club marinas in Bedford Basin which is north of the harbour through the narrows:

Dartmouth Yacht Club is on the east side of the Basin about 1.5 miles past the Narrows. The Dartmouth Yacht Club is close to the largest industrial park in Atlantic Canada. A wide selection of useful services and equipment for visiting yachts is available including fuel dock, chandlery, repairs and provisions.

Website: www.dyc.ns.ca

Contact: Dartmouth Yacht Club, 697 Windmill Rd,

Dartmouth, NS, B3B 1B7. Tel: 468 6050 Fax: 468 0385

E-mail: dyc@dyc.ns.ca.

Bedford Basin Yacht Club is at the head of the Basin about three miles past the Narrows and has a range of facilities. The clubhouse is open Sunday, Wednesday, Friday and Saturday afternoons and evenings.

Website: www.bbyc.ns.ca

Contact: 377 Shore Drive,Bedford, NS B4A 2C7.

Tel: 835 3729 Fax: 835 2047

E-mail: bbyc@ns.sympatico.ca or manager@bbyc.ns.ca

Halifax waterfront:

The Maritime Museum of the Atlantic used to offer free berthing for up to three days on a pontoon just south of SMCS Sackville and CSS Arcadia. Most of the waterfront is now managed and berths are charged. There are very limited facilities for visiting yachts and the berths are subject to the wash from passing vessels.

Further west along the coast of Nova Scotia from Halifax:

Shining Waters Marine is at the head of St Margaret’s Bay (44° 39´30N, 63° 54´42W). It has a full service marina, chandlery, boat storage facility and repair service and is only 30 minutes from Halifax International airport.

Website: www.shiningwaters.ca

Contact: Shining Waters Marine, Tantallon, Nova Scotia B3Z 2P3. Tel: 826 3625, 800 687 1469

E-mail: admin:shiningwaters.ca or marina@shiningwaters.ca

Anchorage and moorings are available off Shearwater Yacht Club north of McNab’s Island and off the yacht clubs in the North West Arm and in Bedford Basin. If entering the North West Arm at night or in poor visibility be aware that there are a large number of yacht moorings and anchorage is prohibited inside a ‘no wake corridor’ which runs up the central third of the entire length of the inlet. Anchoring is allowed outside this centre corridor clear of any moorings. Beware of a rocky shoal patch 60m (200ft) off the western end of Melville Island when approaching Armdale YC. Anchoring is not permitted in the main harbour between McNab’s Island and Point Pleasant or in an area below the first bridge.

There are harbour ferries. A local bus route connects the area, including the North West Arm. Halifax is served by the Canadian National Railway system. The main bus and train stations for the national network are near the southern end of the docks. The international airport is 35km (22 miles) north of the city and has flights within Canada and to the United States and Europe. The airport shown on the plan is for the Services.

There are a number of hospitals and medical centres in Halifax and Dartmouth. Ask locally for contact information.

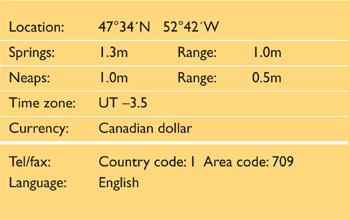

Plan 84 St John’s, Newfoundland, Canada

St John’s sits on the eastern side of the Avalon Peninsula. The peninsular is almost a separate island, attached by a narrow isthmus to the south-eastern corner of Newfoundland. St John’s is the capital and principal commercial port of Newfoundland and is landlocked and well sheltered. It is the oldest English-founded city in North America and has a rich maritime history. Cabot Tower, which sits on the top of Signal Hill overlooking the town, was built in 1897 to commemorate the 400th anniversary of John Cabot‘s discovery of Newfoundland and Queen Victoria‘s Diamond Jubilee. An old hospital building near to Cabot Tower is the site where Marconi received the first transatlantic wireless transmission in December 1901. St John’s was the departure point for another historic first – Alcock and Brown’s successful transatlantic flight in 1919. It continues to be the departure or arrival point for many similar adventures, including yachts crossing the Atlantic by one of the northern routes. Newfoundland has strong Celtic links and there is a lively musical culture – try one of the many Irish pubs in St John’s.

St John’s, Newfoundland: looking west through the inner entrance. The yacht pontoon is central on the far side, to the left of the red building.

Photo: Department of Fisheries and Oceans

The approaches to Newfoundland lie in one of the foggiest areas in the world. However, it is often clearer as you approach within a few miles of the shore. Icebergs carried south by the Labrador Current are seasonally prevalent. Virgin Rocks, and the nearby Eastern Shoals, which lie 100 miles east of Cape Race are a potential hazard on the approach. (See photo on page 71.) Offshore to the east of Newfoundland, the current sets southerly at about 1 knot, but it runs westerly around Cape Race. Be aware of the currents and tides, particularly a strong northerly eddy close in to the south coast of Newfoundland which has caused many vessels to be swept up into the bays along this southern coast. The barren coastline is generally very steep, rising directly to 60m (200ft) in many places. Hills of 150m to 250m (500ft to 800ft) back the shoreline which can be confusing when you are trying to identify the harbour entrance. The bluff coastline can also result in squally winds or wind shadows when close inshore. Vestal Rock, with a depth of 3.7m (12ft), lies 65m (215ft) south-east of South Head. In thick weather it is possible to mistake the entrance to Quidi Vidi harbour (one mile further north) for that of St John’s. Quidi Vidi has no lighthouses or fog signals.

Large ships entering and leaving through the narrow harbour entrance are monitored and controlled by St John’s Traffic. They will need to know when you are within 12 miles of the harbour.

The shore is generally steep-to and clear of underwater rocks, and in thick weather can be approached using the depth sounder. The 40m (130ft) line lies between 0.2 and 0.5 miles offshore. Sugarloaf Head, four miles north of St John’s, has a conspicuous, 168m (550ft) high, sheer cliff face. It appears wedge-shaped when seen from north of northeast, but as a truncated cone from east-north-east round to the south-east. There are a number of radio masts close to the south of it. Cape Spear, 3.5 miles south-east of St John’s, is an 80m (260ft) high promontory, projecting north-eastward from the coast. A light is shown [Fl (3) 15s 71m 20M] from a 10.7m (35ft) white tower, with an old light structure about 200m (660ft) to the south-west.

The final approach to St John’s harbour is between North and South Head and is straightforward. North Head is a steep headland of 72m (240ft) rising up to Signal Hill to the north-west, topped by the conspicuous Cabot Tower. A light [Fl R 4s 26m] is shown from a mast at the entrance. South Head is marked by Fort Amherst Light [Fl 15s 40m 13M], on a square white tower. There is also a fog horn. Enter between the two headlands on a course of 276°. There are daymarks and leading lights [F G 29m and F G 59m] on this bearing, but they are difficult to identify. The twin towers of the Roman Catholic Cathedral break the skyline on the outskirts of the city – the rear light (itself mounted on a church tower) is just to the north of these towers and almost level with their bases. If the leading line cannot be identified, continue on 276° until through the narrows, observing the buoys that mark shoals on both sides of the channel. Once inside, the harbour opens up to the south-west.

St John’s Radio monitors VHF Channel 16 and broadcasts weather forecasts and ice reports. A Vessel Traffic Management System is administered from Signal Hill and should be contacted on VHF Channel 11 or 14 as ‘St John’s Traffic’. The Canadian Coast Guard monitors VHF Channels 16 and 26. In addition, a continuous weather forecast is broadcast on VHF Channel 21B.

Fly the Q flag from offshore if arriving from abroad. When you are about 12 miles from the approach channel to St Johns Harbour, call ‘St Johns Traffic’ on VHF Channel 11. Customs is located on the 6th floor of the Canada building. On arrival, the skipper should go ashore alone to call Canadian Customs Control on 1 888 226 7277 (toll free), with all yacht and personal details to hand – registration number, last port, names and dates of birth of all crew, etc. This number is in operation 24 hours a day. They will want to know the yacht’s exact location and will then issue a Report Number. They will inform local customs who will visit the yacht to stamp the passports of non-US or Canadian nationals. Note that all weapons, firearms and alcohol must be declared and that guns, particularly handguns, may be confiscated and held ashore.

There is pontoon berthing for yachts just south of the leading line opposite the entrance and just to the south of a large red building adjacent to the pilot boat berth. Alternatively, a berth may be found in the small boat harbour in the southwest of the port. There are no services on either of these berths. The harbour is quite polluted, and care should be taken when handling lines that have been in the water.

Looking east from the yacht landing towards the narrows at the entrance to St John’s. Photo: Paul Heiney

The Royal Newfoundland Yacht Club in Conception Bay on the western shores of the Avalon Peninsula, 40 miles by sea from St John’s, welcomes visiting sailors and has a 50-tonne travel lift.

Website: www.rnyc.nf.ca

Contact: PO Box 14160, Station Manuels, Conception Bay

South, NL. A1W 3J1. Tel: 834-5151 Fax: 834-1413

E-mail: manager@rnyc.nf.ca

The harbour is busy and anchoring is only allowed under the direction of the harbourmaster. There is good holding in mud. The harbourmaster’s office is on Water Street.

Daily bus service to Port-aux-Basques (14 hours) for the ferry to Sydney, Nova Scotia. St John’s airport has direct flights to the United Kingdom as well as links within Canada and the United States.

There are three large hospitals in the city, plus many doctors and dentists.

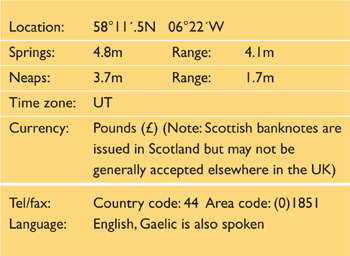

Stornoway is a well-sheltered natural harbour on the east coast of the Isle of Lewis. It is a logical point of arrival or departure for anyone taking the Viking Route across the Atlantic. Although primarily a commercial and fishing harbour, Stornoway welcomes visiting yachts. It may be difficult to find a space in the inner harbour during July when the Maritime Festival, Hebridean Celtic Festival and Highland Games take place. Lews Castle is a prominent local landmark with very pleasant grounds to walk around, giving some lovely views over the harbour and town. If you explore further afield you may be lucky enough to spot some of the golden eagles that are native to the island. The facilities for provisioning and repair are relatively modest in Stornoway, but most things are available if you take local advice.

Stornoway inner harbour showing the yacht pontoons to the left and Poll nam Portan anchorage in the distance. Photo: Clyde Cruising Club

During the day, the large sheds on Arnish Point are a good landmark. The Beasts of Holm at the east side of the entrance are marked by an unlit green beacon. There is a conspicuous memorial on Holm Point to the north of the Beasts. A rock to the north of Arnish Point on the west side of the entrance is marked with a buoy [QR]. North of Arnish Point, on the opposite shore, Sgeir Mhor Inaclete reef is marked by an unlit beacon. At night a series of sector lights lead you into the harbour. Follow the white sectors of Arnish Point light [Fl WR 10s 17m 9/7M], Sandwick light [Oc WRG 6s 10m 9M], Stoney Field (astern) [Fl WRG 3s 8m 11M] and No1 Pier [Q WRG 5m 11M].

Plan 85 Stornoway, Isle of Lewis, Scotland

Stornoway Port Authority VHF Channel 16; Harbourmaster Channel 12.

All vessels must call the Harbourmaster on VHF before entering the harbour. All visitors must report on arrival to the Harbourmaster, Stornoway Port Authority, Tel: 702688, E-mail: information@stornoway-harbour.com

Entry requirements are waived in the case of an EU registered yacht arriving direct from another EU country. In the case of a non-EU registered vessel, or if arriving from a non-EU country or with non-EU nationals aboard, hoist the Q flag and the courtesy flag if appropriate.

Foreign flag vessels or vessels with foreign crew on board must clear immigration through the Port Authority and immigration at Aberdeen Airport. Complete Form NDP(Y), obtainable from the harbour office and fax it to Immigration Aberdeen on 01224 214340. Telephone 01224 722890 for further instructions. Customs clearance should be carried out via the National Yacht Line Tel: 0845 7231110.

Lews Castle, Stornoway. Photo: Clyde Cruising Club

A small marina at the very northern end of the inner harbour has eight visitors’ berths for yachts up to 12m (40ft). Yachts drawing more than 1.5m (5ft) should manoeuvre with caution as depths shallow off from 3.3m (11ft) to less than 1.5m (5ft) in some areas. Larger or deeper draught yachts can tie up alongside the Cromwell Street Quay, or Esplanade Quay (on the north wall to the left of the marina symbol).

Space available in the marked anchorage in Poll nam Portan may be restricted by a number of moorings. Do not anchor in the fairway to the inner harbour. The anchorage can become uncomfortable if a south easterly swell finds its way in.

There are flights to Inverness, Aberdeen, Glasgow and Edinburgh and ferries to Ullapool on the mainland. Buses go around the island.

There are a number of services available, including the Western Isles Hospital in Stornoway (Tel: 704704) and the Health Centres (Tel: 703145 and 704888).

Further south, on the Scottish mainland, Oban Marina offers a full range of facilities including haul-out and storage. Oban Marina (56°25´N, 5°30´W) lies on the shore of Ardantrive Bay, on the east side of Kerrera Island, right opposite Oban itself. It is accessible at all states of the tide and has a full range of facilities including pontoon berths, re-fuelling berth, 50-tonne travel lift and hard standing. Trains from Oban give easy access to Glasgow where there are national and international connections by rail, bus or plane.

Website: www.obanmarina.com

Contact: Oban Marina Ltd Tel: (0)1631 565333

Fax: (0)1631 565888 E-mail: info@obanmarina.com