Plan 2 The North Atlantic showing ports covered in Part II

The timing of passages around the North Atlantic is dependent on the prevailing weather patterns through the seasons. In tropical areas the optimum timings will be when the trade winds are properly established, but avoiding the hurricane season. In higher latitudes, frequencies of gales and the extent of ice fields should be taken into account. At the eastern and western margins, seasonal continental weather patterns become significant.

Winds and weather in the North Atlantic revolve around a central high pressure, the Azores High. This is characterised by a band of variables which usually encompasses the Azores and Bermuda and is surrounded by outer rings of relatively low pressures.

At the western margin, the land mass of North America and the confluence of the warm Gulf Stream with the cold Labrador Current results in unstable conditions. These give rise to a succession of depressions, or lows, which form over the western North Atlantic and are then propelled east or north-east towards Northern Europe. Each of these depressions creates its own wind system anti-clockwise around its centre. The northerly latitudes of the 40s and 50s lie at the bottom edge of these anti-clockwise lows and at the top edge of the clockwise Azores high. This results in a corridor of prevailing westerlies. Gales, caused by steep pressure gradients within the lows, are frequent in this area, but are generally less common and less severe in the summer. In the high latitudes of the 60s it is sometimes possible to pick up easterly winds over the tops of the low pressure systems as they go through.

At the eastern margin during the summer months, the Azores High dominates which, together with low pressure over Spain, causes north easterly winds to become established down the Spanish, Portuguese and North African coasts. The Azores High is generally weaker during the winter months when the band of variables extends to the southern European and North African coastline.

South of the variable band lies the trade wind belt where the winds are predominantly easterly or north-easterly. The trade winds are usually established winds of around 15 to 20 knots, but may be weaker or stronger than this. Because the Azores High fluctuates in its position and its intensity year on year, the trade winds establish at slightly different times and with varying strengths at any particular latitude. The trades have usually not fully established before December or January although, earlier than this, it may be possible to find more reliable winds by heading further south.

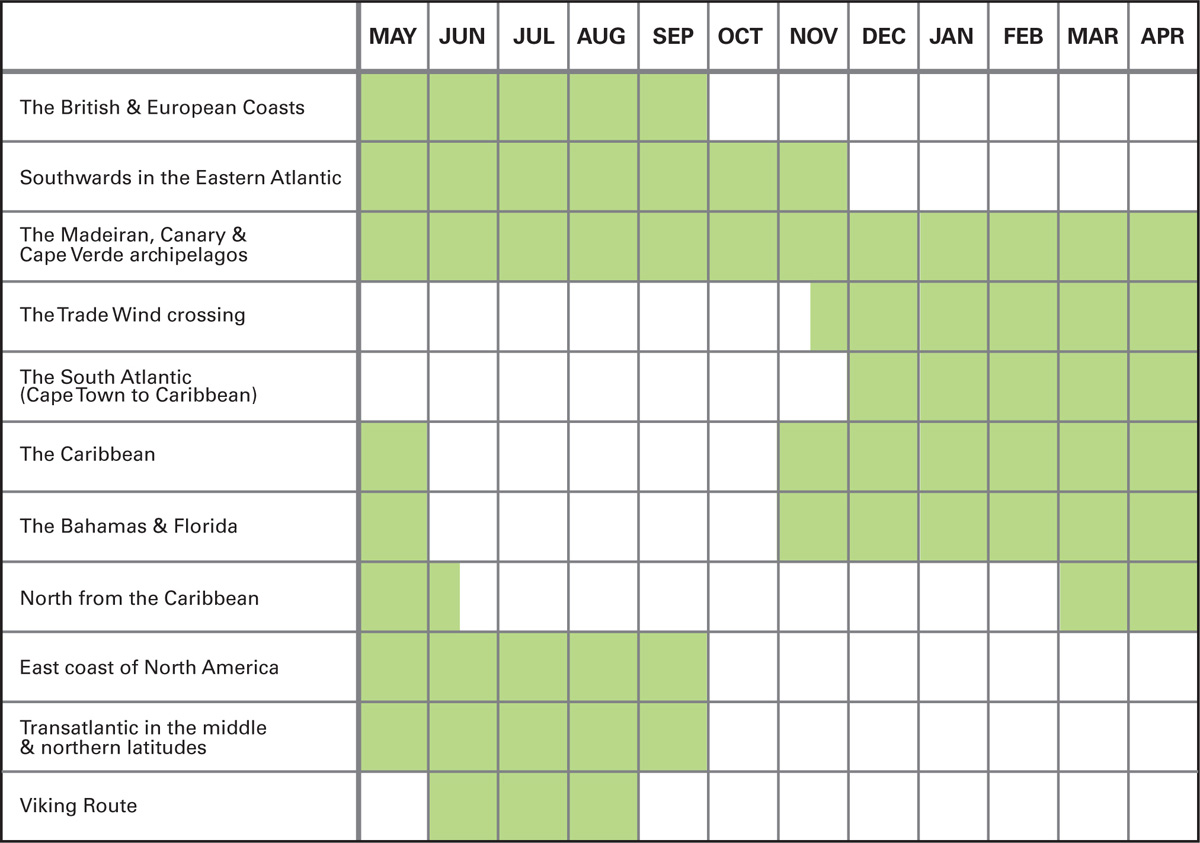

Fig 2 Timing your passages. Green shading indicates the best times for each region.

The Azores High is sometimes disrupted by a cold front which causes a mid-Atlantic trough, resulting in a band of light variables. Further west in the trade wind belt, it is common to experience squalls or even, depending on the season, a tropical wave. Squalls can be intense, with a short but sharp burst of gale force winds. Tropical waves are most common during the hurricane season, indeed they are the progenitor of most hurricanes. Tropical waves are caused by weather systems which form over Africa and then track westwards across the top of the Inter Tropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ). They sometimes carry clear skies, but their passage is more usually characterised by strong south-easterly winds, rain and thunderstorms. See Appendix B.

There is a close but complex relationship between prevailing winds and surface currents (see plans 3 and 4 opposite). Thus the north-east trade wind gives rises to the North Equatorial Current, flowing east to west across the Atlantic between about 10° and 25°N. This creates a head of water in the Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean Sea which becomes the Gulf Stream. This emerges through the Strait of Florida and flows in a north-easterly direction until it meets the Labrador Current flowing south around Newfoundland and Nova Scotia. From 50°W westwards, the interface between the Gulf Stream and the Labrador Current is known as the Cold Wall and is normally very noticeable because of the change in water temperature and in colour – the cold Labrador Current is light green, whereas the warm Gulf Stream is a deep blue. Where it meets the Gulf Stream, the Labrador Current divides. One part forces a passage down between the Gulf Stream and the American coast, and the other turns eastward and combines with the Gulf Stream to form the North Atlantic Current. The North Atlantic Current, urged on by the prevailing westerly winds, eventually meets the obstruction of the continent of Europe. Again it divides, one stream going north of Scotland, and the other being deflected south-east and then south to form the Azores Current, the Portuguese Current and finally the Canaries Current. This in turn feeds the embryonic North Equatorial Current to complete the giant circle.

South of latitude 10°N there is a region of equatorial countercurrent which weakens close to South America. Along the north-eastern shoulder of the South American coastline the southern and northern Equatorial Currents combine into a strong north-westerly flow.

In addition there are local features, such as the currents flowing into the English Channel, the Bay of Biscay and the Mediterranean. There are also vertical currents which are turned downwards from the surface when surface current meets a land mass. So, for example, some of the water arriving at the Caribbean flows down to the ocean floor and back towards Africa. When it meets the African continental shelf it is forced back up to the surface, bringing with it a richness of nutrients which feed an abundance of ocean life in this area.

When a current flows along a continental coastline its course tends to be orderly, but in mid-ocean, or on encountering islands in its path, its track may split or become very ragged at the edges. In some places there are well-documented changes of course due to land masses, and there are areas in which eddies or countercurrents occur predictably. Knowledge of these can be important because parallel courses only a few miles apart may be in waters moving in opposite directions. When this happens the choice of the right track can make a significant difference to the day’s run. In areas where currents run strongly, even moderate contrary winds can create steep and confused seas. Stronger winds, certainly a hurricane, could make the sea state disastrous.

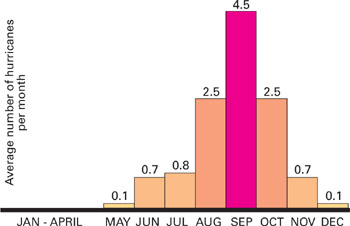

Tropical revolving storms, known as hurricanes in the North Atlantic, are triggered near the equator during the summer months, often as a development from a tropical wave. They form over warm water (27°C or above). They intensify while moving north-west towards the western margin of the North Atlantic between Grenada and Cape Hatteras. They tend to recurve to the north or even north-east, but sometimes continue westwards towards Central America or into the Gulf of Mexico.

An old saying about hurricanes goes:

Hurricanes are among the most destructive forces of nature. Sustained winds can reach 135 knots, with gusts far in excess of that. Huge waves are generated which, depending on the relative track of the storm, may become violently confused. When a hurricane reaches land, the surge associated with it may temporarily raise the sea level by as much as 3–4m (10–13ft). Even large commercial ships encountering such storms are often damaged and sometimes lost. One of the main considerations in timing passages around the North Atlantic should be the avoidance of the hurricane area during the hurricane season. In general, the following advice will minimise the chances of experiencing a hurricane:

Plan 3 General direction of current flow in the North Atlantic – December

Plan 4 General direction of current flow in the North Atlantic – June. Both plans based on information from The Atlantic Pilot Atlas

Yachts piled up on the beach in the lagoon at St Maarten following Hurricane Luis. Photo: Malcolm Page

The National Hurricane Centre is a part of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). NOAA is a US federal agency which focuses on the condition of the oceans and the atmosphere and produces excellent weather reports and forecasts, including hurricane forecasting and tracking.

For more information about hurricanes and storm shelters see Appendix B.

Fig 3 Average number of hurricanes per month in the Caribbean

Fog is common on the coast of Maine and in the region of the Grand Banks. It is most prevalent in spring and summer, and can be expected to occur about ten days in each month. All of the coastal areas on the eastern side of the north Atlantic, from Norway southwards, are subject to fog. European sailors who tend to associate fog with light winds or calms should be aware that this is often not the case in the western Atlantic, where fog may be accompanied by steady winds of 25 knots or more.

Fog is a common hazard in higher latitudes on both sides of the North Atlantic. In some regions it may be accompanied by strong winds. Photo: Richard Woods

North Atlantic icebergs form by ‘calving’ from Greenland’s glaciers, and are then carried south by wind and currents. They are almost totally confined to an area north of 40°N and west of 40°W, though stray bergs have very occasionally been found south or east of this and there is some evidence that global warming is changing this pattern. Icebergs are most widespread between March and July. The International Ice Patrol locates the position of bergs and gives radio reports. Ice reports are also given on Navtex. Further information about ice is given in Chapters 16 and 18.

An iceberg off the entrance to St Johns, Newfoundland in June.

Photo: Paul Heiney

In a printed guide like this it is quite difficult to provide information which will stay in date for all the various weather forecast transmissions. Frequencies and transmission times do change, and the latest technologies are enabling an ever-increasing amount of continuously available information to be transmitted around the world. Nevertheless, the following information should at least put you on the right track to accessing all the weather information you need. Once you are actually on the cruising circuit you will find that fellow cruisers will swap information about what is available and useful. The important thing is to ensure that you have the means to receive such information (see Chapter 5).

Navareas UK – I, France – II and USA – IV

The Admiralty Lists of Radio Signals contain complete details of all weather and safety broadcasts. They also contain details of the NAVTEX broadcasts together with all the harbour and marina frequencies, telephone numbers, websites and e-mail addresses on both sides of the Atlantic.

UK Hydrographic Office: Admiralty Digital List of Lights and Admiralty Digital Radio Signals are available as programs www.ukho.gov.uk/ProductsandServices/Digital Publications/Pages/Home.aspx which can be updated online at updates: www.ukho.gov.uk/adll/

Marine Service Charts (MSC) list frequencies, schedules and locations of stations disseminating NOAA’s National Weather Service products. They also contain additional weather information of interest to the mariner. Charts are available via the Internet. For more information visit www.nws.noaa.gov/om/marine/pub.htm

Once a day an Extended Outlook, published at 2200, is broadcast via each of the UK NAVTEX stations on 518 kHz. The extended outlook signposts expected hazards for the Cullercoats, Niton and Portpatrick areas during a three-day outlook period beyond the period of the 24-hour forecast. The Niton area covers SW approaches to the UK, Portpatrick covers NW approaches. www.bbc.co.uk/weather/coast/shipping/outlook.shtml

UK High Seas forecasts, Met Area 1, are broadcast by the GMDSS Inmarsat EGC SafetyNET service twice a day at 0930 and 2130 UTC. The bulletin is in three parts: storm warnings, general synopsis and forecasts for the sea areas. Storm warnings are broadcast at other times when necessary. At 0800 and 2000 UTC the text of the High Seas forecasts, Met Area 1 is updated on the website: www.bbc.co.uk/weather/coast/shipping/highseas.shtml

Canadian NAVTEX forecasts are in English on 518 kHz and in French on the secondary 490 kHz frequency. Text forecasts and further information can be found on the Environment Canada website: www.weatheroffice.gc.ca/marine/index_e.html

GRIB files (GRidded Information in Binary) is the format used by international meteorological institutes to transfer large data sets and is the foundation of modern weather forecasts. GRIB files are now available as free downloads from the internet. This enables yachts to view weather data for anywhere in the world whenever they want to, and wherever they are. GRIB files can be accessed ashore or on a limited bandwidth connection on board, either by HF radio or satellite telephone. It is possible to choose and save your settings for future use, which can speed up access to relevant data. GRIB files can be downloaded via compression software – which reduces file sizes and minimises the time to download. GRIB files have now largely superceded Weatherfax technology.

BBC marine forecasts 0048, 0520, 1201 and 1754 (local time) daily on Radio 4 LW on 1515m (198 kHz). Also some VHF transmissions. Forecasts give a summary of gale warnings in force, a general synopsis and area forecasts for specified sea areas around the UK (see Appendix D). The radio bulletins at 0048 and 0536 also include the coastal weather reports. Weather information is updated 4 times a day. A text version is posted on www.bbc.co.uk/weather/coast/shipping/. There is also a listening link on the website.

Detailed Inshore Waters forecasts for 19 areas around the coast of the UK are broadcast on Radio 4 LW on 1515m (198 kHz) at approximately 0526 (local time). The forecasts generally cover up to 12 miles offshore and consist of a 24-hour forecast followed by an outlook for the following 24 hours. The forecast for Shetland covers up to 60 miles offshore and consists of a 12-hour forecast followed by an outlook for the following 12 hours. Local radio and Coastguard stations also broadcast on VHF. A text version is posted on www.bbc.co.uk/weather/coast/inshore/.

See Appendix D for BBC and Meteo forecast areas.

Radio France Internationale ‘Le Meteo’ 1130UTC daily on the following AM (A3E) frequencies: 6175kHz in Europe, 15300, 15515, and 17570 and 21645kHz for the Atlantic.

This forecast is the only voice forecast which covers the whole of the trade wind crossing. It is read clearly in French. Even if your French is not very good, you will soon pick up all the necessary vocabulary to understand the forecast. See Appendix C for a translation of terms. Write it down as it sounds and work it out afterwards. You may find that someone on another yacht will give a translation on a daily net.

For more information about forecast transmissions go to: www.marine.meteofrancecom/ Click on ‘Bulletins Large’ or ‘Bulletins Grande Large’.

US Coast Guard Portsmouth, Virginia (call sign NMN)

Western Atlantic north of 3°N and west of 35°W together with the Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean Sea; American High Seas forecast: any hurricane warnings will be transmitted before the forecast. In addition, some broadcasts include a Gulf Stream analysis. This forecast is read by a computer-generated voice synthesiser, which takes some getting used to.

USCG broadcasts offshore forecasts and marine warnings on 2670 kHz following an initial call on 2182 kHz. The ‘Iron Mike’ High Seas HF Voice Broadcast is on 6501 kHz (USB) at 0203 UTC and 1645 UTC.

VHF forecasts Most coastal areas around the Atlantic have local maritime weather forecasts on VHF. Forecasts are usually announced on Channel 16.

On US VHF frequencies, continuous marine weather forecasts are available on one of 10 VHF weather channels and cover all of the USA, Puerto Rico, The Virgin Islands and some of the Bahamas. Depending on your itinerary it may make sense to purchase a US handheld VHF.

US Maritime Safety Information Broadcasts are given on Channel 22A and announced on Channel 16. Further information about US Coast Guard broadcasts can be found at www.navcen.uscg.gov/marcomms/vhf.htm Continuous forecasts for Canadian waters are given on Channels 21B AND 83B. Text forecasts and further information can be found on the Environment Canada website: www.weatheroffice.gc.ca/marine/index_e.html

There is, of course, a degree of personal choice involved in the selection of ports for each region. However, emphasis has been placed on their suitability for making safe landfall. With the exception of ports in Chapter 15 (Dominican Republic, Turks and Caicos and Bahamas), the majority of the primary ports in each section may be approached and entered even in bad conditions and at night and most are official Ports of Entry. The extensive lists of shore facilities from previous editions have no longer been included. It is safe to assume that, unless otherwise indicated, all the ports included have a selection of reasonable facilities for yachts and are appropriate places to prepare for departure or recover on arrival. Many cruising yachts prefer to anchor wherever possible and in this respect the listed ports are not always ideal. No attempt has been made to cover all viable harbours and anchorages for which local cruising guides should be consulted. Further guidelines on the use of this book are as follows:

Further information about ports of call worldwide can be found at www.rccpf.org.uk and at www.noonsite.com (Click on ‘Countries’ and then on the relevant country which will come up in a list under cruising areas. Then select from the list of ports.)

Further information about ports of call worldwide can be found at www.rccpf.org.uk and at www.noonsite.com (Click on ‘Countries’ and then on the relevant country which will come up in a list under cruising areas. Then select from the list of ports.)

The relevant courtesy flags are shown for each port. These are not always the same as the national flag.

The relevant courtesy flags are shown for each port. These are not always the same as the national flag.

The co-ordinates given for each port, rounded to the nearest half degree, are not intended to be used as waypoints. They merely indicate location.

The co-ordinates given for each port, rounded to the nearest half degree, are not intended to be used as waypoints. They merely indicate location.

Bearings, where given, are in true from seaward.

Bearings, where given, are in true from seaward.

Local time (LT), in relation to the Universal Time Constant (UTC), is quoted for each port. In many places, including Great Britain, clocks are advanced during the summer months. The dates when this operates are decided by the government of each country and may vary from year to year. The times quoted are therefore subject to the appropriate adjustment for local ‘summer’ time if applicable.

Local time (LT), in relation to the Universal Time Constant (UTC), is quoted for each port. In many places, including Great Britain, clocks are advanced during the summer months. The dates when this operates are decided by the government of each country and may vary from year to year. The times quoted are therefore subject to the appropriate adjustment for local ‘summer’ time if applicable.

Wind and current diagrams are based on information in the Atlantic Pilot Atlas, James Clarke, Adlard Coles Nautical.

Wind and current diagrams are based on information in the Atlantic Pilot Atlas, James Clarke, Adlard Coles Nautical.

Tidal heights quoted are Mean Level above Datum, as listed in the British Admiralty Tide Tables NP 202. All heights are given in metres.

The IALA A system (red to port, green to starboard when entering a harbour or heading upstream) is standard in European waters, including the Azores, Madeira and the Canaries. The IALA B system (green to port, red to starboard when entering a harbour or heading upstream) is used throughout American waters, as well as Bermuda and the Caribbean.