3

A World without Work

Humans have been out of work for millennia, and they have lived happy and healthy lives despite not having to earn a living. At least that’s what archaeology and anthropology tell us. Our Paleolithic ancestors would have been shocked to witness how stressful, and often vacuous, our modern lives have become because of the necessity to work. For we may take work for granted today, even extol it as a virtue, but the truth is that “work” is the most unnatural thing we humans ever did.1

The invention of work was a watershed in the political organization of human society and is strongly linked with the beginnings of social inequality. Timothy Kohler and his team at Washington University collected measurements of homes on 63 archaeological sites around the world spanning a period from 9000 BC to AD 1500, a period coinciding with the agricultural revolution, during which free-roaming, nonworking human nomads gradually settled to become earth-toiling farmers.2 Comparing the different sizes of homes for each settlement and period, they concluded that, as people started growing crops, settling down, and building cities, the rich started getting richer. Interestingly, they also noticed a difference in wealth disparity between the Old World and America. For instance, the civilization of Teotihuacan, which flourished in present-day Mexico around a thousand years ago, was based on large-scale agriculture and yet wealth disparity was relatively low. Geographical happenstance may be the most likely explanation for this difference.3 Eurasia happened to have more animal species that could be domesticated—such as the ox, for example—while oxlike animals did not exist in pre-Columbian America. The domestication of animals acted as “production multipliers” in the creation of wealth. Owning an ox meant you could plough more land, increase your harvest, and create a surplus. By creating a surplus, you could become a creditor, that is, a “protocapitalist,” to someone who did not own an ox and thus kick-start the economic cycle of credit and debt.4

Economic Abundance without Work

The Aagricultural Rrevolution may have spelled the end of leisure and the beginning of social inequality, but the memory of our simpler Palaeolithic lives was not forgotten. Hesiod, in his poem Work and Days, describes an epoch of economic abundance wheren no one had to work, and “everyone dwelt in ease and peace” to a very old age. That was the “Golden Age of Man,” when humans lived like gods. The Bible recounts a similar story: the first humans, Adam and Eve, lived without worrying about food or shelter, or about the future. Everything was provided for them. Living in the moment, and for the moment, was all that mattered. But once exiled from Eden their lives became a constant struggle against uncertainty. The Almighty decreed besetting work upon us as a dubious blessing: “In the sweat of your face you shall eat bread till you return to the ground . . .”5 And although these words from the Bible have been interpreted by theologians as sanctifying work, the sore reality is that—unless you are rich enough to recreate Eden on Earth—you are doomed to work for most of your productive life in order to earn a living, support a family, and save for retirement. Was it worth it? The social inequality, the need to work and constant worry about the future, the traumatic divorce from nature?

For many years the answer to those questions was unequivocally affirmative. Hunter-gatherer life, once you removed the tinted glasses of romanticizing it, seemed far from ideal, a constant battle against starvation and brutal, untimely death. It was therefore assumed that, as soon as people realized that they could fill their stomachs more predictably by planting and domesticating, rather than by risking life and limb chasing after wild prey, there was no way back. New archaeological data, however, are increasingly revealing a different story:6 the adoption of agriculture, and work, was detrimental to human health and quality of life. Living next to domesticated animals allowed viruses to mutate and infect humans. By taking up farming, our diets became limited and we became less healthy. The lives of hunters-turned-farmers were shortened. Anthropological research into hunter-gatherer societies that persist to this day seems to confirm that. Before transitioning to farming, we were healthier, stronger, and happier, and—importantly—we expended a lot less energy to sustain our lives.

Canadian anthropologist Richard B. Lee conducted a series of simple economic input-output analyses of the Ju/’hoansi hunter-gatherers of Namibia and found that they make a good living from hunting and gathering on the basis of only fifteen hours’ effort per week.7 Moreover, the livelihood of the Ju/’hoansi is very resilient. They have access to and use 125 different edible plant species, each of which has a slight different seasonal cycle, is resistant to a variety of weather conditions, and occupies a specific environmental niche. Compare that food resilience with ours today, dependent as we are on just three crops—rice, wheat, and maize—for more than half of the plant-derived calories we consume worldwide.8 On the strength of this evidence and in comparison with modern industrialized societies, anthropologists consider hunter-gatherers as “the original affluent society.”9 Why? Because the transition from hunting and gathering to agriculture was also a transition from abundance to scarcity; from a world of plenty where one could just walk into a forest and pluck something to eat to a world where, unless you can pay for your food, you will go hungry. Economic theory tells us that the reason for scarcity is that resources are finite and limited, and therefore some decision must be made on how to distribute and allocate them. Before the agricultural revolution such resource-allocation decisions were made easily among the members of a small and mostly egalitarian community of people. But once we became numerous and started living in cities, decisions about the allocation of resources became more complex. Scarcity is therefore not only the raison d’être for economics but the mother of politics too. For who governs how wealth is distributed in a society determines the political system of that society and, ultimately, its destiny.

Work as the Means to Participate in Economic Growth

Our views on the ethical importance of work have changed over the centuries.10 The ancient Greeks—as Hesiod’s nostalgic reference to the Golden Age testifies—viewed work as a burden and as an obstruction to the contemplative life of a truly free person; indeed, for them, “freedom” essentially meant freedom from work.11 The opposite of freedom was slavery, where work was coerced and turned humans into something “less” than complete persons. On the contrary, Christianity regarded work as the road to redemption and sanctified it. The Christian faithful are called the “slaves of God.” But it was the labor and women’s movements that sprung from the social upheavals of the First Industrial Revolution that redefined the meaning of work, in the way that most of us understand it today: neither a burden nor a blessing, but as the path toward self-actualization and personal independence. Work has been deeply embedded into the functioning of industrialized societies ever since. It keeps the wheels of our economies turning by transforming working citizens and their families into consumers. It defines the ever-tense relationship between the owners of capital and the providers of labor. More significantly, work is the means by which we participate in the growth in our country’s economy.

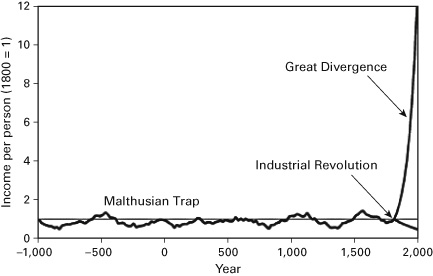

That is somewhat paradoxical, because we may take economic growth as a given and link it to work, but in truth “growth” is something relatively new in human history. For thousands of years following the agricultural revolution there was hardly any economic growth. The vast majority of people worked hard but continued to live in poverty nevertheless. There was simply not enough wealth to go around more broadly. Every time an innovation created an economic surplus, the resulting increase in population quickly consumed that surplus and things went back to the way they were before—in what is called a “Malthusian trap.” But something profound happened as the First Industrial Revolution kicked in in the 1800s, a phenomenon called the “Great Divergence” (see figure 3.1).12

Figure 3.1 The First Industrial Revolution accelerated global economic growth exponentially. Graph based on data from the Maddison project database, by Jutta Bolt, Robert Inklaar, Herman de Jong, and Jan Luiten van Zanden.

Over a relatively short period per capita income increased exponentially. Economic growth—as we presently know it—kicked in. We came out of the Malthusian trap. The First Industrial Revolution created more surplus that people could consume. As a result, the world population started to increase. There were many other drivers for change, ranging from the transition to representational democracy in the West, to the opening up of educational opportunities to the poor, to increased technological innovation. Transportation technologies such as steamships and trains had a decisive impact in boosting international trade and increasing human productivity further. As the latter increased, so did wages and per capita income. To work became the single most decisive factor between staying poor or moving up the social and economic ladder. We may take it for granted nowadays when we think that the economic future of our children and grandchildren is likely to be better that ours, as ours was better than our parents’ and grandparents’, but this expectation is based on the assumption that human productivity will continue to increase thanks to new technological breakthroughs and innovations, and that working citizens will keep on sharing ever-bigger pieces of an ever-growing economic pie.

Alas, the expectation of continuing economic growth that is shared by the working many is severely tested by data. At least until the 1980s, a stable labor income share was accepted as a fact of economic growth. Over the past decades, however, there is evidence of a downward trend for labor share. According to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), the average adjusted labor share in G20 countries went down by 0.3% per year between 1980 and the late 2000s.13 Work is not as important in inflating the economic pie anymore. Capital seems to play an increasingly more important role. To explore the factors driving this trend, and what could be the repercussions for society, the economy, and politics in the twenty-first century, we must turn to the firm as the main organizer of work, examine how the organization of business processes is changing rapidly because of advances in automation technology, and understand how the role of human work is diminishing.

The Firm as Organizer of Work

Nobel Laureate economist Ronald Coase (1910–2013) has offered an economic explanation of why individuals choose to organize by founding a firm rather than by trading bilaterally through contracts in a market. He proposed that firms exist because they are good at minimizing three important costs.14 The first cost saving comes from resourcing: it’s less expensive to find and recruit workers with the right skills and knowledge from inside a company rather than searching for them outside the company every time you need them for something. The second cost reduction is in transacting, or in managing processes and resources: it’s less of an administrative burden to have teams in-house than to manage multiple external contractors. And finally there’s a reduction in the cost of contracting: every time work takes place inside a company, the rules and conditions are implied in the employment contract, and management does not need to continuously negotiate with individual contractors. By reducing these three costs, Coase suggested that firms are the optimal organizational structures for competitive economic activity.

And yet something seems to be going awry with firms and corporations over recent years. The forces that render firms obsolete appear to have accelerated dramatically. Research by Richard Foster of Yale School of Management15 has shown that the average life span of firms has been consistently shrinking, from sixty-seven years in the 1920s to fifteen years today, and dropping fast. At current churn rate, 75% of the S&P 500 will be replaced by 2027. We are witnessing a phenomenon of accelerated “creative destruction,” to use the terms of Austrian-American economist Joseph Schumpeter (1883–1950). This phenomenon picked up the pace at the dawn of the digital era—around fifteen years ago—by claiming the media and entertainment industries as its first victims. Those industries saw their traditional, analogue business models become obsolete as content became digital and virtually free. What happened to those industries is now taking place in banking and insurance, transportation and retail, health care and consulting, to name but a few. In fact, there does not seem to be a single industry that is immune to disruption by digital technologies. If we focus on how work changes because of digital disruption, then we may clearly see how software is now allowing for the three costs that Coase identified to be minimized outside rather than inside a firm.

Resourcing freelance contractors with the right skills via online talent platforms—such as Upwork or Topcoder—can be less costly, faster, and less risky than recruiting full-time workers. Transacting and managing work is also becoming less costly and more efficient using cloud-based software collaboration tools that enable agile, manager-free forms of work of remote teams, many of whom, if not all of whom, may be freelancers. The advent of blockchain technologies—which will be examined later in detail—promises to slash contracting costs by automating contracts with external talent. All these digital innovations are making work easier to resource, transact, manage, and contract out in the market rather than inside a firm. A new form of organization for work, one that is “marketplace-like,” is thus emerging: it is not hierarchical but flat, not closed but open, not impermeable but permeable, not based around jobs but around tasks and skills, not run by human managers but facilitated and optimized by computer algorithms, not siloed in functions or lines of business but highly networked and fluid. This new way of organizing work is called a “platform.”

Platform Economics

Let’s first define what a platform is and make the distinction between a computer platform and a business platform, so we may then trace the connection between those two concepts. A computer platform is the environment in which software applications are executed. For example, a web browser is a web-based computer platform where other applications can run: a website, or some executable code, like a document or a spreadsheet. A business platform is a business model for creating value through collaboration between various participants on a network; it very closely resembles a “marketplace.”

Sangeet Paul Choudary, in his book Platform Revolution,16 describes the shift in corporate business models from what he calls “pipes” (linear business models) to “platforms” (networked business models). Before the digital revolution, firms created goods and services, which they pushed and sold to customers. The flow was linear, like oil pipes connecting production upstream to consumption downstream. Unlike pipes, business platforms disrupt the clear-cut demarcation between producer and consumer by enabling users to create as well as consume value. Platforms need a different infrastructure than pipes. For example, they need specialized hardware and software that enables and facilitates interactions between the firm, business partners, consumers, and other stakeholders, or what is collectively referred to as the “platform ecosystem.” Because platforms resemble marketplaces, where demand and supply must balance, they need to attract sellers and buyers, or providers and consumers, in sufficient numbers in order for transactions to occur; which is often a challenge akin to a catch-22 situation.

Take, for example, a company like Uber. For consumers to be motivated to download the app and order a ride, Uber must ensure that there are enough drivers on its platform. But for drivers to be interested in joining, they need to know that there are enough consumers looking a ride! For this reason, creating a “digital marketplace” (which is another way of describing a business platform) requires considerable initial investment: suppliers have to be incentivized to join even while consumers are still absent, until a critical mass of supply attracts demand and market dynamics kick in.

What appeals to investors who pour millions of dollars into creating a critical mass of supply in a platform is that, once the liquidity of the platform reaches that phase transition point of market dynamics, one gets the so-called network effects. The platform suddenly becomes very attractive to many more suppliers and consumers, which leads to the number and the value of marketplace transactions scaling exponentially. Marketplaces have existed for millennia, of course, but what is different nowadays is that companies are becoming like marketplaces, a transformation facilitated by software, powerful computer servers on the cloud, computer networks, and data. And this is where computer platforms and business platforms come together and often merge. In doing so, they shape the nature, playbook, and dynamics of the digital economy with significant repercussions for innovation and democracy.

During the first era of the Internet, computer platforms were “open” and controlled by the Internet community. Developers were free to build whatever applications they wanted and have them run on those open platforms. It was a world of direct democracy not dissimilar to ancient Athens. But by the mid-2000s the Internet had evolved into “web 2.0,” which included social media features and advanced search engines. Web 2.0 was touted as extending the democratic franchise of the Internet beyond the software developing cognoscenti to include everyone with access to a computer and the ability to post a photo on their social media feed. But instead of more democracy a new oligarchy of five big players emerged: Facebook, Amazon, Microsoft, Google, and Apple, collectively known as “FAMGA.” The business models of those digital behemoths fuse the ideas of computer and business platforms into an unbeatable combination that is generating enormous investor value.

For instance, Google has developed the operating system Android (a computer platform), which enables a three-way marketplace (a business platform) connecting software developers (who write apps), hardware developers (the companies that manufacture smartphones and wearables), and users. Indeed, the explosion of smartphone use has been one of the main drivers for the digital transformation of companies across every industry, since it has radically changed consumer behavior and allowed for highly personalized consumer experiences. This explosion, however, has had several side effects. The first is that the “open” and decentralized computer platforms of the first era of the Internet have been replaced by closed, centralized services offered by big tech companies. The centralization of computer platforms means that software developers and entrepreneurs must abide by rules set by the big tech’s strategic agendas—rules that can change at any time, unpredictably, serving the interests not of the “many” but of the “few,” which usually means the big tech’s shareholders. In other words, the competitive field on web 2.0 is no longer level but profoundly skewed toward the owners of incumbent, closed computer platforms.

Platform Capitalism

The implications of the so-called platform capitalism for working people are considerable. “Digital transformation” pushes traditional companies to radically change their linear, pipelike business models into platforms and imitate FAMGA success. These models do not just reinvent how companies engage with their customers; they also change how work is done. The platform model demands a marketplace for resourcing and paying for work, linking demand with supply in a dynamic and cost-efficient way. As businesses undergo digital transformation, they discover that they need far fewer full-time employees, as they can now engage the necessary skills from a plurality of other sources, such as talent platforms, consultants, contractors, part-time workers, and sometimes volunteers.17 Jobs are deconstructed into tasks, and tasks are either automated or distributed to various suppliers of work. This work deconstruction and task redistribution is orchestrated using specialized software that matches work with skills18 using AI algorithms.

As digital technologies dissolve the traditional organization of the firm and deconstruct jobs into tasks executed by a mix of humans and algorithms, anxiety is growing about the “gig economy”—where work is temporary, skills based, and on demand. The numbers of independent workers are exploding across the developed world. A study by the Freelancers Union found that 53 million Americans, or about 34% of the total workforce, are independent workers, a number expected to rise to 50% by 2020.19 In Europe there is a similar picture emerging, with about 40% of EU citizens working in the “irregular” labor market, according to the European Commission.20 A McKinsey study21 looked in depth at the numbers, as well as at how independent workers feel about work, and confirmed the tension between the positive aspect of going independent, which is flexibility, and the negative, which is income insecurity. Whether you are a driver for Uber, or a financial analyst contracted via Upwork, or a software developer microtasking in some company’s development framework, your livelihood depends on the cyclical fluctuations of demand for your skills, your rating, and your ability to market yourself effectively against the competition. Moreover, residual profits from your participation never reach you but go straight to the owners of the platform, who are not currently obliged to provide participants with the protections associated with employment.22 Add the threat of automation from AI, and the result is a survival-of-the-fittest scenario coupled with a race to the bottom for rewards and benefits.

As many companies around the world begin to transform their organizational models to become more agile, the “platforming” of full-time employees is becoming a top management agenda item. Take Haier, the Chinese manufacturing giant, which is transforming into a platform for entrepreneurship by encouraging its employees to become self-governing entrepreneurs. Zhang Ruimin, the CEO of Haier, sees this transformation as the only path that can secure a future for his company.23 He is removing traditional leadership and replacing it with worker autonomy. Such bold moves may benefit risk-takers but are a threat to workers who value security and stability more. In many cases the replacement of human hierarchies with software systems that orchestrate work clashes with human nature, as in the case of Zappos, the digital shoe and clothing shop currently owned by Amazon. The company employs around 1,500 people and has a billion dollar annual turnover. It has implemented a self-organization methodology invented by a software engineer24 known as “holacracy.” Instead of pyramidal hierarchies, holacracies are organized around “circles”; each circle can encompass a traditional function (such as marketing) as well as other “subcircles” that focus on specific projects or tasks. No one prevents workers from freely moving across subcircles in order to achieve their goals, because there are no managers to stand in their way. Instead, software enables collaboration and the performance of individuals and teams, while “tactical meetings” allow for employees to provide feedback about how things are working in a tightly circumscribed format. Yet despite the flexibility and efficiency holacracy promises, it’s been criticized for not taking into account the emotional needs of workers, and reducing humans into “programs” that must run on the operating system of digital capitalism. Similarly, many Uber drivers often report25 feeling less like humans and more like robots, manipulated by the algorithm in the app, telling them exactly what to do. When jobs are deconstructed into tasks, and those tasks are then automated using AI systems, there is a risk that the human workers of today will be completely transplanted by intelligent machines.

Digitization, Digitalization, and the Automation of Work

The displacement effect of technological disruption is always easier to predict than the compensation effect. That is because most new technologies are invented in order to generate cost efficiencies in the present, which is generally quite well understood. On the other hand, predicting how these technologies will generate a need for “new work” is a lot harder, as there are too many unknowns to calculate. This explains why most of the economic analysis on the forthcoming Fourth Industrial Revolution has concentrated on jobs lost rather than jobs gained. Easier does not, however, imply “easy”: predicting which jobs will be automated—or “displaced”—by intelligent machines, and how quickly this will happen, remains a difficult task wrought with many assumptions and oversimplifications and dependent on the methodological approach economists adopt in making their predictions. Many economist think that the displacement impact of automation will range from considerable to devastating, as, for example, in the famous 2013 paper by Oxford economists Frey and Osborne26 that predicted a loss of 47% of jobs in the United States by 2023. Using a related methodology, McKinsey put the same number at 45%, while the World Bank has estimated that 57% of jobs in the OECD member states will be automated over the next two decades.27

Work automation not only reduces the number of jobs available but also negatively impacts wages. Research by economists Daron Acemoglu and Pascual Restrepo looked into US labor markets and estimated that one more robot per thousand workers reduces the employment-to-population ratio by up to 0.34% and wages by up to 0.5%.28 This seems peculiar: technological innovation has historically boosted human productivity, and one would expect that robots and AI would do the same now and that wages will rise. Indeed, a report by the consultancy firm Bain29 estimated that productivity would rise by 30% across all industries because of automation. And yet, if one combines these two findings, it looks as if the providers of work will not be sharing in the new bounty of automation. Wages will be depressed despite an increase in productivity. This result is even more puzzling if one factors in demographics: the number of workers will decrease in the next decades both in the West and in China, Korea, and Japan. And yet, the decrease in the supply of labor does not seem to lift wages either.

To understand this worrying trend, it is important to distinguish between digitization and digitalization and then proceed with analyzing how digitalization shifts the balance of contribution in economic value creation from human workers to software systems, that is, from labor to capital. Digitization is the process of rendering a physical object in a digital form as zeroes and ones. Scanning a paper document and recording a voice and storing the recording as a digital file are examples of digitization. Digitalization replaces methods of sharing information in a process with computer instruction code. For example, a process whereby a clerk would review a number of paper documents in multiple binders and then walk to the office of her supervisor, three floors up, to wait outside his door and ask for approval, could be digitalized using computer programs. One often needs the digitization of physical objects to happen before proceeding with the digitalization of a process. In the example of the clerical worker, digitizing paper documents and binders into digital files and folders provides the opportunity to develop computer code that digitalizes the process of review and approval using telecommunications instead of physically climbing stairs and waiting for doors to open. Digitalization “automates” tasks in a process, and often the whole process, reducing cost, increasing efficiency, and boosting productivity. Process tasks need not be trivial. For instance the digitization of radiology scans allows for a computer, instead of a medical expert, to perform diagnosis—that is, it allows for the digitalization of the diagnostic process. Digitalization’s other consequence is that it requires humans to acquire new skills in order to compete in the new, “automated” world. In the example of the clerk, the ability to access a computer system and manipulate digital files, use email, and so on are the new skills she needs to retain her job. The fact that the process no longer needs the clerk’s physical presence in the workplace is another profound consequence of process digitalization. Workers and workplaces can be disentangled. The clerk can work remotely and perform the new process. She can be anywhere in the world.

Given the interplay of digitization and digitalization, robots do not replace humans directly; it is the process of digitalization that does so in very unpredictable ways. The roboticist Rodney Brooks gives the example of the human toll collector.30 Developing a robot that would do exactly the same job is hard and inefficient. The dexterity required to reach out and meet the outstretched arm of a driver to collect coins and notes in a windy environment is hugely challenging for a robot with present-day technology. Nevertheless, the human toll worker can be replaced by digitalizing the toll-paying process. For this to happen a number of innovations have to occur. The car must acquire transponder capabilities and transmit digital information regarding ownership; credit cards have to be digitized so they can be charged without the need of physical contact; wages need to be credited digitally into a bank account connected to a credit card, and so forth. Digitalization is therefore an emergent phenomenon that is virtually impossible to predict, because it is the unpredictable combination of technological innovations.

When Humans Are No Longer Needed

Automation technologies are advancing apace. There can be no doubt that they will impact the current economic model of growth in a profound and unprecedented way. It is not necessary for AI to reach, or overtake, “human-level” intelligence, or for the robots to become as “dexterous” as human beings, for human work to be replaced almost entirely by machines. Digitalization does not replace human workers by simulating how humans perform work tasks; it does so by reconfiguring how work is done in a process. This reconfiguration can be significant and replace many tasks that we currently regard as uniquely human.31 Take, for example, how machine-learning systems diagnose cancer by looking into medical images. They do not do so by emulating human experts. Instead, they do so by scanning thousands of medical images and building their own internal ways of drawing inferences from data correlations. They do not need to understand what they do or why they do it. Their “intelligence” is different from ours—it has no semblance of consciousness or self-awareness—but none of that is important. What is important is that intelligent machines can do diagnosis better than human experts, do it faster, and do it at a scale. Also important to note is that a machine is a capital asset. In hospital systems we have capital assets, such as buildings and equipment, and human resources, such as doctors, nurses, orderlies, janitors, and so on. Given what cognitive technologies are capable of, it is not too hard to imagine a hospital system that is highly digitalized and where markedly fewer human resources are needed. In that future hospital the ratio between capital assets and labor will have shifted significantly in favor of the former. In fact, the future hospital may be completely made of software.

The compensation effect has always created demand for new work during past industrial revolutions. But given the exponential rate by which automation technologies improve themselves, we may be reaching a tipping point in history where most of the new work created by AI will be done by AI! Take, for example, Uber drivers: a software-based platform in combination with satnav systems and the digitization of payments has delivered a high degree of digitalization of the process of finding a taxi when you need it. As a result, many microtasks of the process have been automated: as a passenger I do not need to step out onto the street and wait in hope for a passing cab, a taxi driver does not need to know all the streets and alleys of a city to get me to my destination, I don’t have to dig into my pockets for bills and coins to pay the driver, and so forth. This “first wave” of digitalization due to AI has created some new jobs for humans, albeit low-paying ones. Nowadays, almost anyone can be an Uber or a Lyft driver, and many have done exactly that, either as a means of supplementing their income or as their main job. Who doubts, however, that the next wave of the digitalization of the taxi process will be the total elimination of human drivers and their replacement by powerful AIs?

In fact, few people do. According to research by Pew,32 “most [citizens] believe that increasing automation will have negative consequences for jobs” and “relatively few predict new, better-paying jobs will be created by technological advances.” Citizens are clearly aware of the danger that AI-powered automation will destroy their livelihoods, and the data back up their perception. Research on US Department of Labor data by Axios revealed that three-quarters of US jobs created since the 2008–2009 financial crisis pay less than a middle-class income.33 As the US economy is on a record-breaking streak of adding new jobs into the labor market, professions that were once the backbone of the middle class have been vanishing. This “hollowing out” phenomenon is reflected in the current composition of the workforce, which is concentrated mostly on high-skill, high-wage and low-skill, low-wage jobs. Middle-skill, middle-wage jobs are vanishing. Manufacturing—because of the degree of automation already in place—is a good proxy indicator for the future of work, as technological disruption is already impacting more middle-skill, middle-wage jobs across all industries. According to data by the Federal Reserve, 25% of jobs have disappeared from manufacturing in the last two decades.34 Given the exponential rate of technological change, we should expect a much higher percentage of hollowing out of the labor market in a much shorter time frame.

The Fourth Industrial Revolution could lead to the massive digitalization of business processes across every industry. If that happens, human work—as we know it—could become unrecognized. Full-time jobs would become a rarity, and most of us would be working part-time for a wide variety of clients. Meanwhile, society would be reaping handsome dividends from this new transformation of the economy. Machines will be producing goods at a very low cost in fully automated factories—or indeed much closer, in our homes, using 3D printing. Digital assistants powered by AI will be our doctors, financial advisors, and personal agents looking after every aspect of our lives. Innovation will be accelerated across every industry. We can imagine AI systems used by scientists to synthesize new materials that mimic plants and make superefficient solar panels. Solving our planet’s energy and environmental problems at a stroke, we can proceed by using AI to optimize food production and every other process too, so that human productivity rises exponentially. In such a scenario we could, theoretically, fulfill most of our material needs without the need to work and, in effect, return to an era of economic abundance. But there is a caveat.

Unlike our prehistoric ancestors, we now live in highly complex societies with sophisticated power structures and institutions, where wealth redistribution is largely controlled by governments and whoever has the most influence on their decisions. Therefore, a key political question about the Fourth Industrial Revolution is how governments will enact policies that encourage the widest possible sharing of the economic bounty that intelligent machines will deliver to the economy. The risk of not sharing the spoils of the AI economy in a democratic way is rather obvious: ordinary citizens whose only way to acquire income and wealth is through work would sink into a spiraling abyss of abject poverty. Such an outcome would most certainly destroy the last vestiges of trust in liberal democracy. Democratic governments would therefore need to step in and manage the impact of automation on work. They would also need to deal with many other risks and challenges that AI brings, including, the ethics of AI algorithms and the use of personal data in business and government. Governments would need to adopt AI systems in their processes, in order to improve their own performance and deliver better services to citizens. But how far can we—or should we—go with the automation of government? And what should the role of government be in an automated future? Given the potential of AI to automate many cognitive processes at very low cost, as well as its superhuman power for prediction and strategic planning once it processes vast amounts of data, can we imagine a fully automated government, one that is run by intelligent machines rather than human civil servants and politicians? Does it make sense to relinquish control of our economies to intelligent machines with full autonomy? The next chapter will examine in more detail such questions, as well as the different approaches between liberal democracies and authoritarian regimes in shaping the future of AI.