7

AI for Good

Debates on AI consistently juxtapose humans against the machines. Artificial intelligence systems will replace us in the workplace, nudge us into obedience, spy on our innermost thoughts, and ultimately overpower us—if one adheres to the dystopian prophecies of the so-called AI singularity. Therefore, AI must be managed and regulated lest humans become collateral damage to technological progress. This spirit of “humans against the machines” has inspired the European Union’s GDPR, as well as the many initiatives in AI ethics that seem to be popping up everywhere nowadays. To hedge against the negative consequences of AI, economists and ethicists are trying to find common ground and suggest how to balance the economic potential of AI with its ethical implications.1 The automation of work by AI is a fine example of this precarious and much-sought balance between opposing needs. Markets tend to ignore the “social value” of work and focus squarely on efficiency and cost reduction. This creates many negative externalities—for instance, a steep increase in cases of depression among the unemployed followed by the breakdown of social cohesion, which are costs that must be borne by society at large. This is not dissimilar to a factory producing excellent goods at low prices while polluting the environment—and not paying for it. So, as we think about the future of AI, there are many who are trying to find ways to repurpose intelligent systems to deliver social goods and not just cost efficiencies. For instance, economists Acemoglu and Restrepo suggest that societies should choose to invest in the “right type” of AI, one that minimizes negative externalities, and deploy it in areas such as education and health care where most people would benefit.2 They also suggest that tax incentives should be given to companies so that AI systems create new and higher-value work for humans rather than simply automating tasks.

All such proposals are very useful in addressing the impact of AI and its current model of application that benefits mostly the big corporate oligopolies. Nevertheless, these proposals implicitly accept AI technology in the way it is being developed today as a given. In other words, they do not question the foundational nature of AI systems or whether there is an alternative way to design these systems before embedding them in human society. They also largely ignore, or underestimate, a particular characteristic of AI systems that is unique, namely, their potential for autonomy. Autonomy is different from automation. Conventional computer systems automate business processes by encoding in a software program specific steps that the machine has to execute in order to arrive at a logical output. The human programmer determines these steps and is in complete control of the process as well as the outcome of automation. But when it comes to AI systems, the human programmer becomes irrelevant beyond the initial training of the algorithm, and the system evolves its own behavior and inner complexity as it crunches more data. This self-evolution of AI systems is akin to how biological systems learn by interacting with their environment to evolve adaptive behaviors that we perceive as intelligence and autonomy. The highest degree of autonomy is, of course, free will, which we currently defend as uniquely human, although who is to say whether an autonomous AI system won’t exhibit “free will” in the not too distant future. As discussed, current research and effort in AGI aim to develop exactly such systems in the next ten years.3 The increasing autonomy of future AI systems suggests that humans will have even less control over how those systems will behave. Ultimately, a superintelligent autonomous system will be uncontrollable and capable of setting its own goals that may be different than, or in conflict with, human goals.4 Framing the debate on AI as “us versus them”—as we do today—leads to a future battle that we humans are bound to lose, regardless of how smartly we try to regulate this technology for good. Moreover, the outcome of that battle may pose an existential risk to our species and civilization that goes far beyond the aggravations of economic inequality.5

We should therefore reexamine the idea of AI autonomy, understand its origins, and ask if it is a one-way street. Can there be only one future, where intelligent systems and humans struggle to coexist in a tense and uneasy relationship of constant competition and suspicion? Or is there another way to think of machine intelligence, not as something separate from human experience and society, not as the mechanical “other” that is to be feared and regulated, not as the means of reinforcing the dominance of the few over the many, but as something that is purposely built to improve the human condition? To answer these questions, we need to start by tracing the historical roots of AI and identify the moment that gave birth to the idea of machine autonomy. To do so, we need to go back at the dawn of the computer era in the 1950s and 1960s.

Control and Communication in the Animal and the Machine

Artificial intelligence was born out of the dominant scientific and engineering movement of those postwar times called “cybernetics.” The goal of cybernetics was to understand how self-organization occurs in complex systems, but also how emergent systemic behaviors affect the parts that make up those systems. A system is generally described as “complex” when its behavior is different from the behavior of its parts. Take, for example, a flock of starlings; each starling has a certain way—or pattern—that it follows when in flight, but the flight pattern of the flock is completely different, as everyone who has had the joy of watching this beautiful phenomenon knows. The flock exhibits an emergent behavior, something that would be impossible to predict if one knew only how any single starling flies. Such emergent phenomena of self-organization occur all around us and at every scale, from colonies of microscopic algae to the neuronal networks in our brains, the physiology of animals and humans, weather systems, biological ecosystems, and, of course, the economy. They can also occur by design in complex engineering systems. Cybernetics studies the relations between the parts and the whole by analyzing how communication takes place between the parts of the system, looking into what are the various communication pathways that signals have to travel between the parts, what are the messages carried by signals, and how the messages or other characteristics of the signals change over time, and why.6

One of the most profound ideas in cybernetics is “feedback.” Cybernetic systems exhibit emergent behaviors because the communication signals between the parts are traveling in feedback loops; output signals are often mixed with input signals from the environment or other parts of the system and are fed back into the system and so on. Thus, a cybernetic system operates in a recursive way. There can be numerous feedback loops at play in complex systems. What makes feedback loops significant is that they change the internal structure of the system. Take, for example, the human brain, which is made up of billions of interconnected neurons. In order for the brain to make a decision (conscious or not), it processes input signals from the senses, as well as signals from inside the brain that continuously alter the strength of the interconnections between the neurons. The “brain system” is constantly reconfiguring itself as it interacts with the environment, with itself, and with the rest of the body. Like the brain, all cybernetic systems adapt their behavior to changes in their environment and in themselves through sensing and processing multitudes of signals traveling in feedback loops. Cybernetics’ great insight was that this process of adaptation by feedback loops is in effect a process of “learning.” In the case of the human brain this is quite obvious: the mechanism of memory is based on how our brain’s internal structure modulates over time, and how the interconnections between the billions of neurons are either reinforced or weakened.7 The strength and pattern of neural interconnections are further controlled by neurochemical reactions that are modulated via feedback loops.8 The neurobiological mechanism of memory is thus founded in how the internal structure of the brain changes while adapting to both internal and external stimuli and states. However, because of the generality inherent in cybernetic theory, any complex system that adapts its internal structure to a changing environment in order to achieve its goals can also be regarded as a “learning system.”

It thus became one of the most audacious ambitions of cybernetics to develop design principles for how humans and machines could communicate, collaborate, and learn from each other. In 1950 the father of cybernetics, Norbert Wiener, published a book entitled The Human Use of Human Beings,9 in which he expanded on the idea that an ideal future society would be one where machines do all the tedious work, thus freeing the humans to perform more sophisticated and creative tasks. When we look at a future where AI and robotics take over human work, Wiener’s prophetic vision begins to resonate very strongly. However, there is a fundamental difference between how we debate about AI today and how Wiener and other cyberneticians thought about the role of automation technology. Wiener’s concept of human-machine collaboration was based on cybernetic principles of knowledge that required humans firmly embedded within a cybernetic “supersystem.” These design principles start with the idea that some measurements (data) are transformed into organized information (a database), which can then be turned into knowledge through correlation, reasoning, and curiosity (a knowledge base), with the end result being some kind of action. In a cybernetic system, sensors, computers, hydraulics, electronics, and humans form part of a supersystem that increases its collective knowledge as it interacts with the environment over time and thus also increases its degree of autonomy. In a cybernetic scenario, machines and humans are coupled inextricably as they both advance together toward a common goal.

It was from within that intellectual environment that the idea of AI was born. But something profound happened at the historical Dartmouth Workshop of 1956 that founded AI. The aspirations of the new science of AI clearly diverged from the original ethos of cybernetics science, as described in the text of the original proposal: “The study is to proceed on the basis of the conjecture that every aspect of learning or any other feature of intelligence can in principle be so precisely described that a machine can be made to simulate it. An attempt will be made to find how to make machines use language, form abstractions and concepts, solve kinds of problems now reserved for humans, and improve themselves.”10

This foundational statement signified the historical point of departure of AI from cybernetics. The new science of AI was now taking a different view by claiming that it was possible, indeed desirable, to build knowledge machines with complete autonomy. Artificial intelligence thus decoupled humans from machines. This meant that humans were no longer necessary or relevant. Indeed the language of the proposal states that the aim of AI was to make machines at least as intelligent as humans, and probably more so. Artificial intelligence was thus founded as a competition against humans. Progress in the development of powerful digital computers played an important role in AI departing from cybernetics, focusing attention on the machines themselves and how to apply the cybernetic concepts of learning by feedback loops inside a machine.

This core philosophy of AI, of setting intelligent machines and humans apart and often in competition, applies to both its schools of thought, symbolic as well as connectionist. In symbolic AI it led to autonomous systems wherein knowledge was coded in logical rules.11 In connectionist, probabilistic AI, autonomy is manifested in how deep learning systems operate. For example, in a typical setup for supervised learning, training data are labeled by humans and are fed into an artificial neural network. The human contribution is pure input; there is no feedback loop from the machine back to the human that changes the human. Only the artificial neural network changes its internal structure (i.e., the numerical weights of its nodes) through iterations with human-labeled data. In the case of unsupervised learning or reinforcement learning, the AI system is totally decoupled from humans and learns by itself, as the system AlphaGo Zero by DeepMind demonstrated.12 The history of AI is marked by “milestones” where machines beat humans: in chess, in Jeopardy!, in Go, in cancer diagnosis. Such milestones are celebrated as signs of technological progress wherein the machines improve themselves and become more intelligent than humans in narrow domains until “artificial general intelligence” comes along and machines become smarter than us in everything.13 As the authors of a paper on AlphaGo Zero proudly stated, “Starting from tabula rasa, our new program AlphaGo Zero achieved superhuman performance, winning 100–0 against the previously published, champion defeating AlphaGo.”14 By celebrating their system’s victory over the human, the authors were expressing the dominant AI ideology of the past sixty years, which implies a future in which machines surpass humans. Nevertheless, there is another way to think of AI.

Searching for an Alternative AI

Let us return to cybernetics and explore how a different kind of AI may be possible, one in which humans and machines are not adversaries but partners working together toward a more human-centric world. By way of illustration, let us take conversational agents, where current approaches of NLP are used in applications such as chatbots and digital assistants.15 To reimagine these human-machine conversations using cybernetics, we may look into the work of Gordon Pask (1928–1996), an English cybernetician who made significant contributions in a number of scientific fields including learning theory and educational psychology. Pask developed a theory based on the idea that learning stems from the consensual agreement of interacting actors in a given environment, which he called “conversation theory.”16 Conversation theory postulates that knowledge is constructed as the result of a conversation, and that this knowledge then changes the internal structure of the participants in that conversation. These participants may be humans but may also be humans and machines engaged in dialogue. Pask suggested that the knowledge resulting from such conversations could be represented in what he called “entailment mesh.”

Entailment meshes encapsulate the meaning that emerges in a conversation by two participants—say, between A and B. For participant A, the one who initiates the conversation, the mesh encapsulates the topics of the conversation as well as what makes them different, in what Pask termed “descriptive dynamics.” For example, say A wanted to talk with B about immigration. The descriptive dynamics of A’s entailment mesh would include concepts such as “number of immigrants,” “economic impact of immigration on GDP,” “multiculturalism,” and so forth. She would then need to explain how these topics interact to make a new concept, for example, a “policy for immigration control” (this aspect of the entailment mesh is called “prescriptive dynamics”). Participant B would then need to deconstruct the meaning of A’s entailment mesh and reconstruct it in terms that he would understand, then feed this reconstructed understanding back to A. A would then need to change aspects of her entailment mesh, both descriptive and prescriptive, in order to “close the gap” of understanding between her and B. Through such conversational iterations between A and B, a common understanding is achieved, which can be the basis for collaboration, negotiation, agreement, or action.17

For comparison, let us look at the most advanced conversational agent we have today that uses the traditional, connectionist approach in AI. In 2019 OpenAI released a limited version of a conversational system called GPT-2.18 The system was trained on a data set of around 8 million web pages, making it capable of predicting the next word in any 40 GB of text. This relatively simple capability was enough for the system to generate impressively realistic and coherent paragraphs of text, as well as beat many benchmarks in reading comprehension, summarization, and question-and-answer conversations. Nevertheless, there were also certain limitations that are typical of AI systems that learn on preexisting data. For instance, GPT-2 would perform well with concepts that were highly represented in the training data (such as Brexit, Miley Cyrus, Lord of the Rings, etc.) and poorly with unfamiliar texts. Researchers are currently trying to address this weaknesses in the current approach of probabilistic AI, for it fails to capture new meaning in novel conversations or texts, as well as support conversations beyond simple questions about a priori known facts.19 It is also telling that OpenAI restricted the release of the full training model of GPT-2 based on concerns over the malicious use of the algorithm in deep fakes. In other words, our most advanced conversational systems today are deemed “dangerous” for society because they can hack our brains and restrict our freedom. Arguably, this is happening because current AI aims to imitate humans by adhering to the core ideology of system autonomy. While doing so, AI systems also struggle to become the truly collaborative tools that we actually need.

Pask’s entailment meshes could offer an alternative, and more human-centric, route toward artificial conversational agents. Conversation theory principles could be used to connect concepts in the context of a conversation and the meaning that needs to be conveyed. Second, concepts would evolve as a result of the conversation, which means that the memory of the conversation can be implicit in an entailment mesh. This memory may also signify how a particular participant likes to approach learning, what his or her style is. Do participants prefer to be given the “big picture” up front—what Pask termed as “holists”—or do they learn quicker through examples. Entailment meshes can therefore be used to improve personalization. Moreover, this dynamic coevolution of humans and machine—or “knowledge calculus” to use Pask’s terminology—is much closer to how our brains learn.

Ultimately, this example of the cybernetic approach of entailment meshes—an instance of “cybernetic AI”—could result in human-machine systems that have goals that are shared between humans and machines. This is in contrast with today’s AI that is decoupled from the humans while advancing its own goals. Therefore, to de-risk the existential threat of AI and deliver a human-centric future, it is not enough to simply regulate AI and hope for the best. Instead, we should adopt a top-down approach in how we build intelligent human-machine systems based on cybernetics. This holistic approach requires the design and construction of learning systems wherein humans and intelligent machines collaborate to achieve common goals. These learning systems can be then embedded in any human organization, commercial or noncommercial.

By deriving inspiration from Pask’s approach in building conversational machines, we could also make AIs exhibit behaviors that go beyond the mere exchange of a conversation and reach a level that we generally associate with “theory of mind.”20 Theory of mind is one of the most important cognitive abilities of the human brain and is essential for empathy and understanding. We develop this ability between the ages of three and four, when we begin to “hypothesize” that other people around us also have “minds” that are different from but also similar to ours. It is because of theory of mind that we have the ability to empathize with other people’s feelings and intentions. Theory of mind is the cognitive mechanism of moral behavior; it makes us feel how others feel—or would feel—as a result of our actions. The memory of conversations, as embedded in entailment meshes, could deliver artificial systems that empathize with humans and help us achieve our personal goals. Current AI approaches lack such cognitive ability, as they personalize through mere statistical segmentation—that is, by grouping us with others with “similar” characteristics. In the context of a democratic polity, and since language is the medium of human communication, politics, and consensus—and theory of mind is the key to empathy—we would need to envision and develop a new breed of conversational agents capable of emulating empathic behaviors. Instead of restricting access to such AI systems for fear of limiting our freedom—as OpenAI did with GPT-2—we should be doing the exact opposite: designing, developing and deploying systems that amplify our potential and provide us with more degrees of freedom and liberty. Let’s see an example of how this could be achieved, in the case of citizen assemblies.

Embedding Cybernetic Conversational Agents in a Citizen Assembly

We saw how citizen assemblies have the potential to solve knowledge asymmetries between experts and nonexperts by leveraging the dynamics of deliberation and dialogue. Setting up citizen assemblies is currently very costly and cumbersome. Nevertheless, it is not difficult to imagine how we could apply information technologies and develop software applications that can reduce those costs and thus make citizen assemblies easier to set up and, therefore, more frequent and popular. And we could go several steps further than that, by borrowing ideas from Pask’s conversation theory, imagining intelligent conversational systems that exhibit empathy and theory of mind and using them to facilitate citizen assemblies.

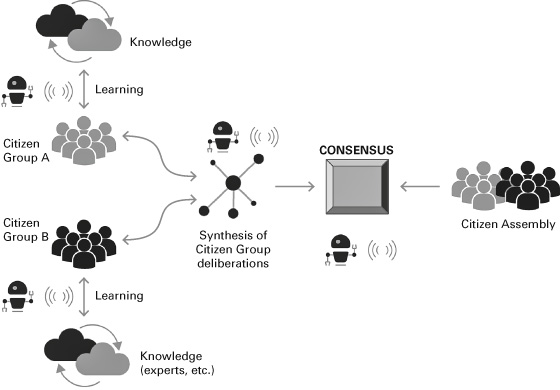

Figure 7.1 depicts a potential design for a citizen assembly in which cybernetic conversational agents enable facilitation, translation, recording, and reporting. Such agents could free up resources and allow for scalability. In order for those agents to not simply automate but become part of the overall human-machine system of democratic deliberation, they must perform the following tasks:

- Understand the context of the debate, that is, what the assembly and the groups aim to achieve. This understanding can be effected through a human-machine dialogue whereby entailment meshes encapsulate the evolving consensus among citizens.

- Facilitate knowledge discovery and acquisition; the intelligent agent acquires (or “learns”) meta-knowledge about a citizen’s goals in order to help the citizen find and acquire necessary knowledge. This is different from an AI search based on keywords. Often the citizen would not know a priori what knowledge is required in order to search for it. Therefore, the agent needs to engage in a conversation with a citizen, understand the citizen’s learning style, and use an entailment mesh to advance the combined, and evolving, knowledge of both the agent and the human around a specific topic.

Figure 7.1 Using cybernetic conversational agents to facilitate a deliberative process while preserving humans in the loop. ©2019 by George Zarkadakis.

- Perform knowledge assessment: the agent should evaluate how much trust the citizen should place in the knowledge discovered and make relevant recommendations. Automating the search for truth is an extremely difficult problem, as current AI approaches are discovering. Although it is possible to automate part of the trust assessment process, for example, by ranking sources in terms of reliability, complex ideas require critical thinking to distinguish fact from opinion that present intelligent machines are incapable of. Assessing the reliability of a knowledge source has to become part of a continuous dialogue between machines and humans. By iterating and learning from this dialogue, the human-plus-agent system can quickly optimize on trusting or mistrusting sources of knowledge.

- Translate: in cases where knowledge acquisition needs to be translated and also when members of citizen groups or the assembly speak different languages. This is an area where standard AI approaches in language translation could deliver an adequate outcome.

Conversational intelligent agents could also be used at the group or assembly level to perform the following tasks:

- Empathic monitoring: sense the feelings of citizens and be able to feed back to the deliberating process an indication of polarization versus consensus.

- Performance of constitutional checks: flag proposals that may be contrary to constitutional law or in conflict with other laws.

- Timekeeping: ensure that the deliberation process can progress on the basis of agreed time intervals and permissions.

Citizen assemblies have the potential to help the evolution of liberal democracies toward a more inclusive and participatory model of government. Cybernetic AI has the capability of accelerating this journey by delivering cost-effective solutions for citizen assemblies at scale. Nevertheless, there may be a much greater prize than this in our quest to reimagine democracy in the era of intelligent machines: to extend cybernetics in the way intelligent machines connect and interact with human society in order to solve the current problems of exclusion, surveillance, and marginalization.

Democracy as a Cybernetic System

There are many ways of thinking about a democratic polity, as described and discussed in various political science books over many centuries. But what if we thought of such a polity in cybernetic terms? To do so, we must agree at the outset that the difference between democracy and authoritarianism is the degree of freedom that citizens have, and that in a democracy citizens are freer. Of course, the problem with freedom is that it—by itself—does not guarantee positive outcomes. For example, people may freely elect the wrong leaders—as history has repeatedly demonstrated—and those leaders may lead the people to ruin. Therefore, what distinguishes a successful free society from an unsuccessful one is how the citizens make decisions in order to govern themselves—that is, their system of government. Governance in society is a complex matter that includes legal, procedural, institutional, and ethical aspects; however, it is also at the heart of cybernetic theory. Indeed, cybernetics’ purpose is the design of successful governance in complex systems. So let us test whether it makes sense to transfer some concepts from cybernetics into the discussion about the future of liberal democracy.

A key concept worth exploring is a special state of equilibrium in complex systems called homeostasis. Again, the image of the flock of starlings is useful as a depiction of this special state. At any moment, the flock looks as if it is about to dissolve into its constituent parts, with single birds flying independently in all directions. And yet, the birds somehow regroup, and the flock continues its magnificent, fluid dance in the sky. This perilous dance at the edge of chaos is what homeostasis, a key characteristic of complex system behavior, looks like. Cybernetic systems exhibit such resilient behavior by using multiple feedback loops to reduce entropy and prevent themselves from decomposing under the second law of thermodynamics. Entropy is the degree of disorder in a system; the higher the entropy, the greater the disorder. The second law of thermodynamics states that the universe has a tendency to increase entropy. We know that from experience too; when a plate falls on the floor and breaks, it is impossible to put it back together as new. Indeed, as the cosmos expands and the degree of disorder in the universe increases, the ultimate destination of everything is the so-called heat death. The only resistance to the formidable second law of thermodynamics is life. Living biological systems are special because they manage to remain ordered and reconstitute themselves continuously by reducing their entropy. Our living bodies are in fact cybernetic systems in a state of knife-edge equilibrium—homeostasis—fighting death at every moment. If homeostasis breaks down irreversibly because of a trauma or a disease, the second law of thermodynamics wins and we die, that is, our bodies begin to decompose into their constituent, molecular, disorderly parts. For cybernetic systems to exist and achieve their goals, they must remain in homeostatic equilibrium.

By observing homeostatic systems, the Chilean cyberneticians Humberto Maturana and Francisco Varela suggested that self-organizing systems are also self-creating; they are, as they said, “autopoietic.”21 Autopoietic systems are self-referencing systems that create the stuff that makes them; take, for example, a biological cell in which enzymes create the proteins and proteins create enzymes. Maturana and Varela also showed that autopoietic systems evolve and thus provide us with an excellent theoretical framework for understanding biological evolution, but also evolution in more general terms—for example, personal, economic, or social. Autopoietic systems can be “first-order cybernetic systems” when humans are the observers of the system—when, for example, a biologist observes a living cell through a microscope. But when humans become part of the system, they become “second-order cybernetic systems,” where the observer and the observed become one. The most important difference between first- and second-order cybernetic systems is that the latter have greater freedom and autonomy—they can set their own goals. This is a very significant difference. We humans are a second-order autopoietic system: self-sustainable and capable of self-realization as well as setting our own goals, given our consciousness and free will.

Applying this theoretical framework to democracy, we can think of a democratic polity as a system of government made up of conscious humans that act together as a second-order autopoietic supersystem: where citizens are both the subjects that deliberate and the objects of deliberation.22 This circular relationship between cause and effect, subject and object, and the parts (citizens) and the whole (assembly) is characteristic of a cybernetic system. As a second-order cybernetic system, an ideal democracy should have the ability to evolve and adapt in an ever-changing environment by achieving homeostatic equilibrium (i.e., consensus) around a common goal. An example of such a common goal would be to maximize the production and distribution of social goods by selecting among a number of policies.

Reframing the dynamics of a democratic consensus using cybernetic terms is useful not only because it gives us new insights into the nature of democratic politics but also because it allows us to take the next step and ask this question: How can a democracy evolve? And evolve it must because the environment—geopolitical, economic, climatological, and technological—never stays the same. New threats will always challenge the survival, cohesion, and economic development of a democracy. New technologies will be invented that will present new risks and challenges, as well as new potential for growth. Citizens will grow old and die and be replaced by younger generations who may think and feel differently than their parents and grandparents. And, of course, citizens must evolve individually too, become more responsible and self-confident by living the citizenship experience of a self-governing polity.

We saw how socialist Chile used cybernetics in the 1970s in order to achieve its economic and social goals. Cybersyn was a learning system that was embedded in the part of the socialist polity that was responsible for economic planning. The governance of Cybersyn was not dissimilar to how oligarchies use intelligent information systems today: collecting data from the edges and centralizing decisions at the core. This hub-and-spokes model of Cybersyn reflects a political philosophy that prioritizes expertise and centralized power. Cybersyn is therefore a good fit for digital authoritarianism. For liberal democracy we need a different architecture for cybernetic systems: they need to be decentralized and look more like a network of equal nodes. Such decentralized, cybernetic, networked democratic models of governance can then be embedded into the institutions of a liberal democracy in order to provide the necessary collective resilience and ability to evolve, while respecting individual freedom, dignity, and independence.

Decentralization has been an inspiration to technologists for quite a while. The philosophy behind the Internet was, arguably, pushback to the centralization inherent in monolithic computer systems and an attempt to develop alternative computer architectures that could not be controlled by a central authority. That philosophy made the Internet more resilient to catastrophes and made it a platform for enhancing democracy. But the evolution of the Internet in its web 2.0 iteration has led to disappointment. Instead of democratic dialogue, we have ended up with echo chambers of hate speech; instead of more economic diversity, we have found ourselves dependent on an oligopoly of supersized tech corporations. Thankfully, there is now new hope. For out of the debris of the global financial crisis a new technology was born with the potential to revolutionize computing and the digital economy, as well as to provide a technological platform on which cybernetic models of decentralized, democratic governance could be built.