Figure 38.1 The circus at Caesarea Maritima in modern-day Israel, c.20 BCE. Source: Photograph by Odemars. Used with permission.

Amphitheaters are the entertainment venue we most associate with the Romans, but the range of other types of venue for spectator events across the Roman world was impressive. This chapter will examine three key spaces used for sport and spectacle in the Roman world: circuses, stadia, and artificial lakes. (Amphitheaters are discussed in Chapter 37.)

It is important to bear in mind that although each of these venues was closely associated with a specific kind of sport or spectacle they tended in fact to be multipurpose. This was often already true at the time of their construction, although they might also be modified at a later date if necessary. For example, the circus is normally thought of as a venue for chariot racing, but it also became a favored location for beast hunts (venationes), although these could also be staged in the amphitheater (Jennison 1937: 42–59; Dodge 2011: 47–62; see also Chapter 34). Both athletics displays and theatrical performances, which were presented as entertainment between chariot races, were also an important part of the activities that took place in circuses (Simpson 2000).

It is also necessary not to lose sight of the fact that over the centuries public areas and buildings other than those listed above housed sport and spectacle. For example, the Forum Romanum in Rome was the site of gladiatorial combats (Vitruvius On Architecture 5.1.2) and crocodiles were displayed in the Circus Flaminius in Rome (Dio Cassius 55.10.8) (see Map 25.1 for a plan of ancient Rome that shows the location of these sites). These spaces needed little modification and any additional facilities could be provided and then removed when no longer needed.

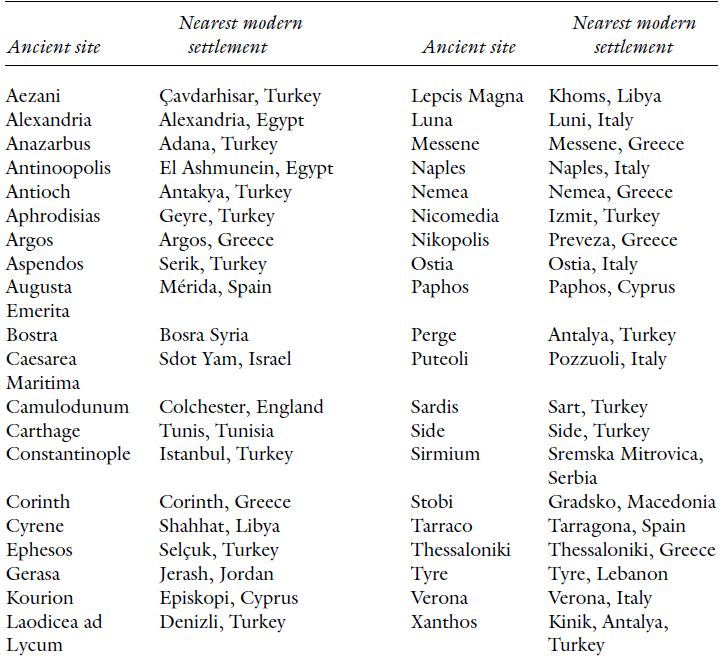

The sheer number of relevant sites makes it impossible within the bounds of this essay to provide detailed maps showing the precise location of each site. In the discussion that follows, most references to lesser-known ancient sites are followed, in parentheses, with the name of the modern-day country in which they are located. At the end of this essay is a list of all the ancient sites named in the text and the nearest modern-day settlement. Readers interested in precisely locating individual ancient sites are encouraged to make use of that list in conjunction with an Internet-based mapping program.

The circus, particularly in its developed form, was largely a Roman invention. In the Greek world only minimal provision was made for chariot and horse racing. A flat area large enough for the racetrack (hippodromos) was all that was really necessary (Humphrey 1986: 5–11; Dodge 2008: 133–4). In spite of the fact that the Greek hippodrome and Roman circus differed markedly, the Greek term hippodromos (literally “horse track”), the equivalent to the Latin word circus, was often used by ancient writers and in inscriptions for circus structures in the eastern, Greek-speaking part of the Roman world. This practice is invariably followed in the modern literature (see Humphrey 1986: 5–12 for further discussion).

The circus was the largest of the various venues for sport and spectacle in the Roman world (Humphrey 1986: 1–4). The size of the circus was significant because of the purpose of the building: it had to be large enough to accommodate, at least in Rome, up to 12 chariots in a race. Thus, the length of the arena1 at the Circus Maximus in Rome was approximately 580 meters with a width of about 79 meters (and an external length of between 600 and 620 meters) (Humphrey 1986: 124–6). The arenas in most western circuses are 400 to 450 meters long (for example, Augusta Emerita (Spain) and Lepcis Magna (Libya)). In the eastern provinces there is much greater variation in size, and the smallest example, with a length of 250 to 300 meters, is only slightly longer than the track in a standard stadium. There is good evidence to suggest that these shorter structures might have served as venues for both equestrian and athletics events (Humphrey 1986: 571–2; Weiss 1999; Dodge 2008).

Racetracks in circuses were divided down the middle by a central barrier and were separated from the audience by a high wall (see the reconstruction of the Circus Maximus in Figure 25.1). Modern-day discussions frequently state that Romans called the central barrier a spina, but in fact its standard designation in the Roman world was euripus (Humphrey 1986: 175–6). One of the reasons for this terminological confusion is that euripus initially referred to the channels dug around the perimeter of the arena in the Circus Maximus in 46 BCE in order to help protect spectators from animals during beast hunts. When those channels were filled in, the term euripus was transferred to the barrier running down the middle of the track. The wall separating the seating area from the arena, the podium, provided a safe vantage point for spectators.

Circuses were often designed so that the two long sides curved slightly outwards about halfway along. This made the events on the track more easily visible to spectators. It also gave extra space where the chariots most needed it: as they straightened up after having swept around the turning posts.2 This feature can clearly be observed in many circuses, for example, at Augusta Emerita and Antioch (Turkey) (Dodge 2008: 137). It also appears in some stadia, beginning with the fourth-century BCE stadium at Nemea (Greece) (Miller 2001: 29–37; Welch 1998b: 548–50) and continuing through Roman-era stadia such as the one at Aphrodisias (Turkey).

The largest of all Roman circuses was the Circus Maximus in Rome, situated in the valley between the Palatine and Aventine Hills (LTUR 1.272–7; Humphrey 1986: 56–294). It was also the earliest to develop. For a long time the structure was fairly insubstantial, with seating either directly on the hill slopes or in the form of timber bleachers. There were no proper starting gates until 329 BCE (Livy 8.20.2); their original form and how they functioned is unknown.

In the early second century BCE the circus started to acquire more definite facilities. The euripus took on a more permanent form with turning posts at both ends each consisting of three adjacent markers; this very distinctive feature is depicted in circus mosaics of the Imperial period (31 BCE–476 CE) (Humphrey 1986: 208–46). In 174 BCE the first of two sets of lap counters was provided in the form of seven eggs (Livy 41.27.6).

Julius Caesar carried out some modifications to the Circus Maximus (Pliny Natural History 36.102; Suetonius Julius Caesar 39.2). He changed the lowest tier of seating from timber to stone and added the aforementioned channels, which separated the track from the seating (Humphrey 1986: 73–7).

In the closing decades of the first century BCE, the lap counting mechanism was refurbished by Agrippa, who also provided a second lap counter in the form of dolphins. The installation of a second mechanism seems to have been motivated by mistakes that were being made in counting the laps (Dio Cassius 49.43.2). Although these lap counters often appear in Roman circus iconography, as well as in Hollywood films, it is still unclear exactly how they worked (Humphrey 1986: 260–5).

By the time of Augustus a number of statues and trophies had been erected on the euripus of the Circus Maximus, although the details of their appearance and relative locations are only supplied by literary and artistic evidence (Humphrey 1986: 174–294). Water basins also adorned the central barrier and were common to all circuses. It is clear that the Circus Maximus provided a major showcase for Roman culture and achievements. A good illustration of this is the red granite obelisk from Egypt erected by Augustus in 10 BCE in the Circus Maximus as a monument to celebrate his conquest of that country (Humphrey 1986: 269–72). The erection of this obelisk, which now stands in the Piazza del Popolo in Rome, initiated a practice of placing obelisks in circuses in various parts of the Roman world. Examples of Roman circuses with obelisks include the Vatican Circus and the Circus of Maxentius in Rome (Golvin 1990) as well as the circuses at Tyre (Lebanon), Caesarea Maritima (Israel), and Constantinople (Turkey) (Golvin 1990; Dodge 2008: 137).

Another significant innovation introduced by Augustus was the construction of an enclosed seating area, the pulvinar, along the northern side of circus, on the slopes of the Palatine Hill. The use of the pulvinar was reserved for those presiding over the games and is clearly depicted with a pedimented, hexastyle façade on a mosaic found at Luna in northern Italy (Humphrey 1986: 78–83).

During the reign of Trajan (98–117 CE) the Circus Maximus underwent a major transformation (Humphrey 1986: 100–15). The whole building was given a monumental aspect with increased seating and massive supporting substructures of brick-faced concrete at the curved southeast end. The exterior façade was reconstructed with arches, in the manner of the Colosseum and the Theater of Marcellus, as shown on a contemporary coin (Dodge 2011: 19). Modern estimates of seating capacity at the Circus Maximus vary from one hundred and fifty thousand to three hundred and fifty thousand, with the latter quite credible for the Trajanic building (LTUR 1.272–7).

As a result of their vast size, few circuses have been completely excavated. One of the best-preserved and most thoroughly investigated is at Lepcis Magna (Humphrey 1986: 25–55). This circus, which was built in the second century CE, lay east of the city, next to the shoreline. To the south was an amphitheater built in 56 CE, and when the circus was completed the two were connected by open passages and tunnels carved through the hillside (Golvin 1988: vol. 1: 83–4). The unification of these two classes of entertainment building in a single architectural complex is unparalleled elsewhere in the Roman world. The arena of the circus was almost exactly 450 meters in length, making it one of the longest after the Circus Maximus.

In common with other Roman circuses, the starting gates at Lepcis Magna were placed along a shallow arc so that all the chariots had the same distance to travel to the narrowed gap to the right of the near turning post. Gaining a good position in this initial gallop was often crucial to the outcome of the race. The uniquely fine preservation of the starting gates at Lepcis Magna allows a reconstruction of the opening mechanism by means of which the races were started (Humphrey 1986: 157–68). An attendant pulled a lever that activated a catapult mechanism, which in turn jerked out the latches of the gates of each stall and allowed the gates to fly open all at once. Presumably a similar arrangement was found in other circuses, including the Circus Maximus. At the end of the seventh lap, instead of returning down the track to the starting gates the teams would round the turning point and head up to the finish line roughly two-thirds along one side. (On the details of Roman chariot races, see Chapter 33.)

Compared to amphitheaters and theaters, circuses were relatively rare in the Roman world. They were generally provided at a later date (second century CE onwards) and marked a city out from others as a center of power. The remodeled Circus Maximus often provided the design inspiration.

There are only three securely attested circuses in the Gallic provinces: at modern-day Arles in the south of France, at Vienne just south of Lyon, and at Trier in the Moselle valley of Germany (Humphrey 1986: 388–411).3 The existence of other circuses has been suggested, notably at Lyon, although no physical evidence has yet been recovered (Humphrey 1986: 409–37).

Chariot racing was particularly popular in the Iberian peninsula, and the remains of over a dozen circuses are known (Humphrey 1986: 337–87; Basarrate and Sánchez-Palencia 2001). Two particularly well-preserved examples are at Augusta Emerita in the southwest and at Tarraco in the northeast (Humphrey 1986: 362–76 and 339–44; Basarrate and Sánchez-Palencia 2001: 75–95, 141–54). Both date to the second century CE, but they differ in terms of location. The circus at Augusta Emerita lies outside the city walls whereas at Tarraco the circus was built on a terrace within the urban center and in association with the Temple of the Imperial Cult. Recent work has identified much of the seating area’s substructure, which is preserved in the lower storeys of later buildings. The position of this circus emphasizes the important ideological connection between Roman spectacle and the imperial cult. Further, both these cities were provincial capitals, a conjunction that can also be observed at Carthage (Tunisia), Antioch (Turkey), and Bostra (Syria).

In 2004 the first circus to be identified in Britain was found at Colchester, which was the Roman colony of Camulodunum and an early provincial center for the imperial cult (Crummy 2008a, 2008b). The circus was situated outside the walled town to the south and dates to the mid-second century CE. Nothing now survives above ground. Its overall length of 447 meters has been established by excavation.

In the eastern Mediterranean, where both chariot and horse racing were already well-established before the Roman period, monumental circuses do not appear as uniformly as in the West, either in location or design (Humphrey 1986: 438–539; Dodge 2008). Based on literary, epigraphic, and iconographic evidence, a number of eastern cities staged chariot racing at one period or another (Humphrey 1986: fig. 205), but fewer cities are known to have possessed a monumental circus. The cities that did tended to be major Roman cultural and administrative centers, such as Antioch and Tyre. Interestingly, there are only two attested monumental circuses in Greece: one recently excavated at Corinth (Romano 2005) and the late third-century CE circus at Thessaloniki. In Asia Minor (modern Turkey) there are only three: Nicomedia, Anazarbus, and Antioch, and nearby there is the example at Constantinople probably constructed when Septimius Severus refounded Byzantion (Humphrey 1986: 438–61; Dodge 2008; see Chapter 43). In Egypt two circuses have been physically identified, one being at Alexandria and the other being the magnificently preserved (under the sand!) example at Antinoupolis; several others are known from documentary sources (Humphrey 1986: 505–16).

There were essentially two types of circus structure built in the eastern Mediterranean (Dodge 2008), and they present a number of interpretational problems. The larger form of building (found, for example, at Tyre, Antioch, and Bostra) had close similarities with circuses built in the West in terms of overall proportions and dimensions (about 400 to 450 meters in length). The smaller type, with examples at Gerasa (Jordan), Corinth (Greece), and Caesarea Maritima (Israel) (all three excavated and published in the last two decades), were much shorter at about 300 meters (Dodge 2008; Ostrasz 1991, 1995; Romano 2005; Weiss 1999). (The circus at Caesarea Maritima is illustrated in Figure 38.1.4) They all had starting gates, although the number varied, and they all had some kind of central barrier, both features being absolute necessities for a Roman-style circus (Humphrey 1986: 18–24). This variation in size, along with the evidence from recent excavations, suggests that circuses in the East were more multifunctional than in the West. Literary evidence for Caesarea shows that athletics and possibly gladiatorial displays were accommodated, as well as chariot and horse racing, and animal displays (Josephus Jewish Antiquities 16.136–8, Jewish Wars 1.415; Weiss 1996, 1999).

Figure 38.1 The circus at Caesarea Maritima in modern-day Israel, c.20 BCE. Source: Photograph by Odemars. Used with permission.

On occasion in ancient literature these smaller circuses are referred to as “amphitheaters” (Josephus Jewish Antiquities 15.341). This has caused considerable debate among modern scholars about the terminology that should be used to describe these structures. Two suggestions are “amphitheatrical-hippo-stadia” and “multi-functional audience buildings/structures” (Humphrey 1996; Dodge 2008). However, even with these new terms, which are in practice not terribly helpful, there is a great detail of inexactitude in their use. They further emphasize the need to rethink modern scholarly approaches to Roman spectacle venues in general. The multifunctional nature of the physical form that can be observed in the complex at Caesarea is paralleled by a number of other structures in the eastern provinces, notably the stadium at Aphrodisias and the theater at Stobi.

The association between circus spectacle on the one hand and politics and the emperor on the other is particularly evident in the juxtaposition of the circus and the imperial palace. That juxtaposition appeared first at Rome with the Palatine palace and the Circus Maximus and was emulated in the Tetrarchic capitals in Milan, Thessaloniki, and Sirmium (Serbia), as well as the Circus of Maxentius on the Via Appia just outside Rome.

The stadium, a Greek building type designed to accommodate footraces and other athletic activities, was well established by the end of the fourth century BCE. By the Roman period it was usually rectangular with one curved end and had an average length of 180 to 200 meters. (On Greek stadia, see Chapter 18.)

It is clear from iconographic and literary evidence from across the Roman world that toward the end of the period of the Roman Republic (509–31 BCE) athletic activity came to occupy an increasingly prominent place in Roman society. In the past, modern scholarship has been quick to follow the traditional line, mainly based on Roman literary sources, that athletic activity of the kind long popular in the Greek world never found favor in Rome and the western provinces. However, recent work on literary, iconographic, epigraphic, and archaeological evidence has shown that this standpoint requires considerable adjustment (Newby 2005; König 2005). Even so, in the West the only identifiable purpose-built athletics venues were in Italy, specifically at Rome, Naples and Puteoli (Aupert 1990; Newby 2005: 36). There is epigraphic and artistic evidence attesting athletic festivals at the modern-day cities of Nimes, Marseilles, and Vienne in the south of France, as well as at Gafsa in Tunisia, although no specific structures have been identified. Athletics also found another home in the context of Roman public baths and private villas (Newby 2005: 45–140).

Greek-style athletic contests were held at Rome long before permanent facilities were built to accommodate them. The first recorded display of Greek athletics in Rome took place in 186 BCE when Marcus Fulvius Nobilior staged a lavish set of games as part of his triumphal celebrations. This was also the first time a beast hunt (venatio) was presented in Rome. Both displays presumably took place in the circus as entertainment between races (Livy 39.22.1–2; Crowther 2004: 381–5; Newby 2005: 25–6). Athletic contests, particularly boxing and wrestling, could just as easily be accommodated in a temporary structure, either a theater or a stadium. Both Julius Caesar and Augustus constructed temporary wooden stadia on the Campus Martius (Sear 2006: 54–7). Caesar constructed his building for the athletic contests associated with his quadruple triumph in 46 BCE (Suetonius Julius Caesar 39.3). Augustus made similar provision in 28 BCE as part of his Actium victory celebrations (Dio Cassius 53.1.5). Nero may also have constructed a temporary stadium for his short-lived Greek-style games, the Neroneia (Coleman 2000: 241; Newby 2005: 28–31). (For more detailed discussion of the history of Greek sport in Rome, see Chapter 36.)

Domitian built Rome’s first permanent stadium in the Campus Martius in 86 CE. This stadium housed the Greek-style contests, the Capitoline Games, that Domitian established in honor of Jupiter (Suetonius Domitian 4.3; Newby 2005: 31–7). The foundations and outline of the stadium have been preserved by the modern Piazza Navona. It was the first stadium to be raised on vaults instead of being banked on earth; this development was presumably inspired by the theaters and amphitheater of contemporary Rome. Its external length of 275 meters makes it one of the largest stadia known from antiquity. Its track length was approximately 192 meters long and hence conformed to Greek practice.5

The two other stadia known in the West were both located in southern Italy on the Bay of Naples. A stadium was built at Naples for the Sebasta festival, a set of Greek games founded in 2 BCE to honor Augustus (Crowther 2004: 93–8). Antoninus Pius established a set of Olympic-style games at Puteoli in c.142 CE in honor of his adoptive father Hadrian (Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum 10.515; Scriptores Historiae Augustae Hadrian 27.3). The associated stadium was substantial at over 330 meters in length (Humphrey 1986: 571–2). Recently work has been carried out on the building but very little has yet been published.

In the eastern provinces many major cities had a monumental stadium, some already provided before the Roman period, for example at Messene and Athens in Greece, although the latter was rebuilt in the mid-second century CE (Aupert 1990: 99–101). In Asia Minor and further east most of the stadia were Roman-period constructions, although their modern study is hampered by a lack of systematic excavation. The (presumably) second-century CE building at Perge in southern Turkey is one of the best-preserved stadia of antiquity. The traditional hairpin-shaped structure is 234 meters long and 34 meters wide. Twelve rows of well-preserved seats were supported on inclined barrel vaults and provided accommodation for some twelve thousand spectators. The entrance to the performance area lay at the southern end, but only a few fragments survive of the monumental gateway marking this entrance. Spectators entered through every third vault, while doors between the vaults allowed access from one vault to another. The vaulted spaces supporting the seating were used as storerooms, workrooms, and shops, especially during the festivals held in honor of Artemis (Abbasoġlu 2001; Dodge 2010: 266–7; Grainger 2009: 94–97, 103–8, 173–5, 196–7, 209–10 and fig. 20; Golvin 1988: vol. 1: 245). Other Roman stadia are preserved at Ephesos and Aspendos (Turkey), and Kourion on Cyprus.

At Aphrodisias there is a particularly interesting and well-preserved stadium that dates to the later first century CE (see Figure 38.2). Unusually, it terminates at both ends in a curve, thus enclosing the whole track with seating. Built entirely of stone, it is 262 meters long and 59 meters wide at its broadest point; it is thus slightly larger than a traditional stadium. Its 30 tiers of seats could have accommodated approximately thirty thousand spectators. As in circuses, the long sides were not parallel but bulge out slightly at their center to allow for better spectator viewing. The epigraphic record from Aphrodisias is vast and there is plenty of evidence for athletics contests, but that evidence also indicates that the stadium was used for more Roman types of spectacle such as beast hunts (Roueché 1993: 61–80 and nos. 14–15, 40–1, 44). A podium wall, 1.60 meters high, that surrounded the performance area was part of the original design and had holes cut into the stonework for timber uprights to support nets (Welch 1998b: 558–9; Dodge 2008: 140–2). These features were useful primarily during beast hunts. The fact that they were provided at the time of construction shows that the building was intended to be multifunctional from the outset. This is not an isolated example. Similar provision was also made in the mid-second century CE in Herodes Atticus’s rebuilding of the stadium in Athens (Welch 1999: 127–32).

Figure 38.2 The stadium at Aphrodisias in modern-day Turkey, late first century CE. Source: Photograph by D. Enrico di Palma. Used with permission.

The presence of a wooden post and net system to protect distinguished spectators has long been reconstructed for the Colosseum (Gabucci 2001: 127–8; Connolly 2003: 196–8), but definitive evidence and reconstruction of such an arrangement was first properly explored following excavation of the second-century CE theater at Stobi in Macedonia (Gebhard 1975). This structure was built from the outset to function as both a theater and an amphitheater. Evidence for such arrangements has also been recorded in the modifications to a number of theaters in Greece and Asia Minor. Our knowledge of the details of these post and net systems is enriched by a description given by the mid-first century CE poet Calpurnius Siculus of an arrangement used in Nero’s temporary amphitheater on the Campus Martius in Rome. A fence with netting surrounded the arena and was topped by some kind of device with horizontally mounted metal rollers that, by turning, prevented animals from gaining purchase and thus being able to jump over (Eclogues 7.50–6; Scobie 1998: 211–12). The rather comedic effect would no doubt have appealed to a Roman audience while frustrating and angering the animals.

Two other stadia are similar to Aphrodisias and further demonstrate the generally varied nature of the provision of entertainment buildings in the East. The stadium at Laodicea ad Lycum in western Turkey, erected in 79 CE in honor of the emperor Vespasian, has the same plan as at Aphrodisias. A length of nearly 350 meters makes it twice the usual dimension for a stadium (Golvin 1988: vol. 1: 243; Humphrey 1996: 123). Surviving dedicatory inscriptions refer to the building as a stadion amphitheatron leukolithon, literally an “amphitheatral (i.e., surrounded by seating) stadium of white stone” (Inscriptiones Graecae ad res Romanas pertinentes 4.845, 861). The epigraphic evidence attests to the building’s use for both athletic and gladiatorial contests (Robert 1940: nos. 116–20). The stadium at Nikopolis in northwestern Greece has a very similar plan, although it is shorter. It was almost certainly constructed for the Actia, the victory games instituted there by Augustus after the Battle of Actium (see Chapter 36).

Another stadium worthy of detailed comment is that at Aezani in northwestern Turkey. It was probably built in the second century CE and is placed with its open end, where the starting line would be situated, up against the exterior of the stage-building of the theater. The seating is supported on earth banks. A similar arrangement can be found elsewhere in Asia Minor at Sardis (Vann 1989: 59–65) and presumably added flexibility and variety to both venue and type of show. Further modifications of stadia in Late Antiquity are discussed below.

Starting in the first century BCE aquatic spectacles of various kinds were held in a number of places in the Roman world. Augustus, for example, in 2 BCE staged an elaborate set of games during which he had the Circus Flaminius in Rome flooded. Thirty-six crocodiles were then released into the pool created, which were subsequently hunted down and killed (Dio Cassius 55.10.8).

The most elaborate aquatic spectacles took the form of naval combats staged at sites in and around Rome. Aquatic spectacles in Rome were most often accommodated in a large artificial basin, a naumachia or stagnum. The former term came to be used for the spectacles themselves, particularly sea battle reenactments (Coleman 1993: 50).

The first recorded aquatic spectacle in Rome was staged by Julius Caesar in a specially built basin in the Campus Martius in 46 BCE (Suetonius Caesar 39.4). The basin was filled in after the event (Dio Cassius 45.17.8) and nothing now survives to give any indication of size and scale. However, to judge from the numbers of ships and men involved, it was constructed on a very large scale. The battle was fought between two fleets that represented Tyre and Egypt and included a variety of ships with two, three, and four banks of oars manned by some four thousand rowers and two thousand combatants (Appian The Civil Wars 2.102; Coleman 1993: 49–50, LTUR 3.38).

Augustus, as part of the games he staged in 2 BCE, held a naval battle in a huge artificial lake that he had built on the right bank of the Tiber River (LTUR 3.337; Taylor 2000: 174–90; Coleman 1993: 50–5). The brief autobiographical statement that formed part of Augustus’s will claims that this lake, referred to in the ancient sources as a stagnum, measured a colossal 1,800 by 1,200 Roman feet (536 by 357 meters, Res Gestae 23). Literary descriptions indicate that it had an island incorporated into its design, but the overall shape of the pool is unknown. It may have been planned as an ellipse, giving maximum all-round visibility for the spectators, but close examination of the orientation of modern buildings in the area has suggested that it had a more rectangular shape (Dodge 2011: 64–5). Augustus’s stagnum was fed by a new and largely subterranean aqueduct, the Aqua Alsietina (Frontinus Aqueducts 11.22). An estimated 270,000 cubic meters of water was necessary to fill the basin. The water inside must have been at least 1.7 meters deep to allow for the use of oars as well as realistic drowning. Augustus states that 30 large and many smaller vessels, which were brought into the basin from the Tiber via a canal, manned by three thousand marines and an unspecified number of rowers took part in the battle. Dio Cassius (55.10.7) and Ovid (Art of Love 1.171–2) inform us that the opposing fleets played the parts of Persians and Athenians, who had fought a number of famous naval battles in the fifth and fourth centuries BCE. The combatants were probably but not certainly condemned criminals who fought to the death (Coleman 1993: 67; Dunkle 2008: 193; but cf. Wiedemann 1992: 90).

Augustus’s stagnum remained in at least intermittent use for a considerable period of time. It was the site of some of the larger shows staged in conjunction with the inauguration of the Colosseum in 80 CE (Suetonius Titus 7.3) and it may have been the place where Philip the Arab held a naumachia in 247 CE (Aurelius Victor Caesars 28). It had been filled in before the end of the third century CE when a new fortification wall was built over the top of it (Coleman 1993: 54).

Trajan (ruled 98–117 CE) constructed a stagnum in the area to the northwest of Castel Sant’Angelo (Prati di Castello) in the vicinity of the significantly named eighth-century CE church, S. Pellegrino in Naumachia (LTUR 3.338; Taylor 2000: 245–7). This site is mentioned in an inscription dated to 109 CE (Inscriptiones Italiae 12.1.5 pp. 200–1), along with a sea battle. Little is known of its form; however, it was probably a rectangular structure, smaller than Augustus’s stagnum but with a minimum capacity of 44,400 cubic meters.

Two naumachiae merit special attention. The first is that held by the emperor Claudius on the Fucine Lake, located about 50 miles east of Rome, in 52 CE (Dunkle 2008: 194–6). This was the largest known naumachia and involved nineteen thousand condemned criminals manning full-scale naval vessels, triremes and quadriremes (Tacitus Annals 12.56). The participants were divided into two fleets, representing the “Sicilians” and “Rhodians.” The Praetorian Guard took part in the battle by manning rafts equipped with catapults and ballistae. The condemned criminals saluted Claudius with the words “Ave imperator, morituri te salutant” (“Hail emperor, those who are about to die salute you!”) (Suetonius Claudius 21.6; Dio Cassius 60.33.3–4). It is a common – but erroneous – assumption that these words were regularly spoken by gladiators prior to combats in the arena. This salute was unique to this occasion and seems to have been an appeal for mercy.

Another particularly noteworthy occasion came in 80 CE when Titus celebrated the opening of the Colosseum with an elaborate series of shows that included aquatic spectacles. A key question involving the aquatic spectacles staged by Titus is whether they involved flooding the Colosseum. A series of epigrams written by Martial (Spectacles 27–30, 34; Coleman 2006: 195–217, 249–59) to commemorate the occasion shows that Titus’s games included more than one naumachia, a reenactment of the myth of Leander swimming across the Hellespont to see his beloved Hero, a pantomime involving the sea goddesses called the Nereids, and a chariot race on a partially submerged track. Martial places some of these events in Augustus’s stagnum, but he describes one of the naumachiae as taking place in a venue that could be quickly filled and drained. This description seems to rule out Augustus’s stagnum, which would have required days to fill. In his description of Titus’s games, Dio Cassius mentions two naumachiae, one held in Augustus’s stagnum and another held in the Colosseum (66.25.2–4).

The evidence provided by Martial and other authors about the siting of Titus’s aquatic spectacles can be supplemented from other sources. Dio Cassius (61.9.5, 62.15.1) claims that Nero on two separate occasions staged a naumachia in Rome in a theatron6 that was immediately afterward drained and used as a site for a staged land battle or gladiatorial combat. Amphitheaters from elsewhere in the Roman world were equipped with basins in their arenas. Finally, Suetonius (Domitian 4.1) states clearly that Titus’s brother and successor, Domitian, flooded the Colosseum for a naumachia.

These sources have created heated debate among scholars about whether or not the Flavian amphitheater really was capable of supporting large-scale water spectacles at the time of its inauguration (Coleman 1993: 58–60; 2000: 234–5; 2006: 195–9; Gabucci 2001: 148–59; Connolly 2003: 139–61, 185–206). Despite recent architectural and archaeological work on the substructures beneath the arena, there is still no consensus on the subject. This area of the building was much remodeled by Domitian and later emperors. It is true that it is lined with waterproof mortar (opus signinum) and that there are drains that would allow the evacuation of water in some quantity (Gabucci 2001: 234–40). There is, however, no trace of a system capable of providing the necessary volume of water to flood the arena. Equally, there have been no adequate estimates of the amount of time it might have taken to both fill and empty the arena. The displays referred to by Martial could possibly have been accommodated in a smaller temporary pool or basin involving far less water.

Large and elaborate aquatic spectacles were staged chiefly in Rome; they were held far less frequently and on a much smaller scale elsewhere in the Roman world. The amphitheaters at Verona (Italy) and Augusta Emerita (Spain), in the form they took in the late first century BCE and early first century CE, had shallow, almost cross-shaped basins beneath the arena floors (Golvin 1988: vol. 1: 109–10, 169–71; Golvin and Reddé 1990; Coleman 1993: 57). These basins were fed by aqueducts and provided with drainage channels. The shallow depth of these basins (approximately 1.25 meters) and the presence of an aqueduct water supply suggests that they may have been used for aquatic displays. The floorboards could presumably have been removed for such an event and replaced for the rest of the program. Naturally, any aquatic display performed in such a restricted basin would have been a very modest affair. Perhaps these structures were used for spectacles of a nonviolent nature, such as some of those described by Martial during the inauguration of the Colosseum.

Aquatic spectacles may not have been very common in the provinces but there is good archaeological evidence from Late Antiquity for a number of theaters, particularly in the eastern Mediterranean, being modified to allow the orchestra to be flooded. Examples include theaters at Corinth and Argos in Greece (Traversari 1960). The theater at Argos was originally built in the fourth century BCE. In the Early Roman period the seating area was extended on both flanks and the circular orchestra was bisected by the addition of a Roman style masonry stage-building. At a later date still, probably in the later fourth century CE, a high wall was placed around the orchestra and an aqueduct was provided to flood the arena. In the theater at Paphos (Cyprus) a wall at the base of the seating area was constructed in the later third century CE so that the orchestra could be flooded (Green and Stennett 2002). The theater had already been modified with facilities for beast hunts and gladiatorial games. At Ostia (Italy) the theater associated with the Piazzale delle Corporazione was converted in the fourth century CE to accommodate aquatic displays, with water tanks placed beneath the seating (Dodge 2010: 258; 2011: 76–7).

Venues for Roman spectacle and entertainment often accommodated more than one type of display and were provided with the necessary facilities to do so as part of their original design. However, buildings could also be modified and adapted at a date well after their construction. This happened particularly in the eastern provinces, where amphitheaters were not so common and other buildings, especially theaters (both pre-Roman and Roman), were altered to accommodate gladiatorial combats and beast hunts (Golvin 1988: vol. 1: 237–49; Moretti 1992; Dodge 2009: 38–41). The remodeling varied from the addition of a wall, usually just over a meter high, around the orchestra, for example in the South Theater at Gerasa (Jordan) (see Figure 38.3) and the theater at Bostra (Syria) (Golvin 1988: vol. 1: 246), to something much more substantial involving the removal of the lowest rows of seats to create a much higher podium wall and an arena. Notable examples of the latter type of remodeling can be seen at Ephesos, Xanthos, and Side in Turkey (Sear 2006: 334–6, 377, 380; Dodge 2009: 40). When the theater at Corinth was remodeled in this way the resulting arena was some 13 meters in diameter and the podium wall was painted with scenes of animal displays (Sear 2006: 392–3; Dodge 2009: 38).

A particularly clear example of this type of modification can be seen at Cyrene (Libya). The magnificently sited Greek theater at the west end of the sanctuary of Apollo was converted sometime in the second century CE by the elimination of the stage and the deepening of the small orchestra to form the arena of a small amphitheater. The seating on the north, seaward side was carried on arches. The arena was carved into solid rock and a tunnel had to be cut to allow the movement of animal cages around the arena (Golvin 1988: vol. 1: 96–7; Sear 2006: 291–2).

In addition to theaters, the stadia and the shorter circuses in the eastern provinces could also be adapted for arena games. This usually took the form of the insertion of a curved wall into one end, creating an elliptical enclosed performance area. There are many examples: the stadia at Athens, Perge, and Aphrodisias and the circuses at Gerasa and Caesarea Maritima (Golvin 1988: vol. 1: 237–49; Weiss 1999: 34–5; Sear 2006: 43–5; Dodge 2009: 41). The dating of this feature is problematic, often merely stated as “late” in publications. What is particularly noteworthy is that scholars have usually assumed that such modifications indicate a rise in the popularity of gladiatorial games, whereas other evidence suggests that the high point of munera in the East was in the second and third centuries CE. The correct conclusion may be that they were intended primarily for beast hunts (Dodge 2009: 41–2).

Figure 38.3 The South Theater at Gerasa in modern-day Jordan, originally constructed in late first century CE. Source: Photograph by Diego Delso. Used with permission.

Sport and spectacle found many roles and venues in the Roman world, but the distribution of the different building types does not necessarily reflect the popularity or presence/absence of a particular spectacle type. This is especially clear in the case of gladiators and amphitheaters. Structures built for sport and spectacle were multifunctional, often coming to accommodate a range of displays. A further challenge is the lack of consistency and exactitude in the ancient terminology used in the written evidence. The importance of entertainment and leisure in the Roman world can be judged by the plethora of theaters, amphitheaters, and bath buildings that survive across the Empire. Huge amounts of money were poured into providing the cities of the Empire with fitting venues for a range of entertainments and they developed a sociopolitical importance that resonates down the ages. The finance for these projects came from a variety of sources, but from the Late Republic donating such facilities was identified as an appropriate mode of self-advancement by prominent figures.

Moreover, some forms of sport and spectacle were accommodated in other spaces. In the Greek world physical exercise regularly took place in gymnasia (see Chapter 19). In the Roman world the bathing process achieved greater social importance, but exercise was also an integral part. This is not only reflected in the provision of exercise spaces within bath buildings, but also in the decoration. The Baths of Caracalla in Rome incorporated large mosaics depicting athletes. The changing room in the Porta Marina Baths at Ostia features a particularly striking black and white mosaic depicting athletes weightlifting, wrestling, and boxing, evoking the exercises in which the bathers took part. Similar images were painted on the walls of a latrine in a bath complex at Vienne (France) (Newby 2005: 78–82).

List of key ancient sites mentioned in this essay, and corresponding modern sites

ABBREVIATIONS

LTUR = Lexicon Topographicum Urbis Romae

NOTES

1 Arena in this case refers to the level area in the interior of the circus, an area that was surrounded by seats that defined its boundaries. The track occupied much but by no means all of a circus’ arena.

2 The euripus was often slightly offset, further allowing more space where the chariots most needed it as they negotiated the turning points (metae).

3 Circuses in North Africa other than Lepcis Magna include those at Dougga, Cherchel, and Carthage (Humphrey 1986: 321–36).

4 There were two circuses at Caesarea Maritima: the relatively short one built by Herod and a longer one that dates to the second century CE. On the latter, see Humphrey 1986: 477–91.

5 On Domitian’s stadium, see Lee 2000: 229–30 and LTUR 4. 341–4. The definitive work on the stadium is Colini 1943.

6 The term theatron here probably but not certainly designates an amphitheater.

REFERENCES

Abbasoġlu, H. 2001. “The Founding of Perge and Its Development in the Hellenistic and Roman Periods.” In D. Parrish, ed., 173–88.

Amr, K., F. Zayadine, and M. Zaghloul, eds. 1995. Studies in the History and Archaeology of Jordan V. Amman.

Aupert, P. 1990. “Évolution et avatars d’une forme architecturale.” In C. Landes, V. Kramérovskis, and V. Fuentes, eds., 95–103.

Basarrate, T. and F. Sánchez-Palencia. 2001. El Circo en Hispania Romana. Madrid.

Bergmann, B. and C. Kondoleon, eds. 1999. The Art of Ancient Spectacle. New Haven.

Cariou, G. 2009. La naumachie: Morituri te salutant. Paris.

Coleman, K. 1993. “Launching into History: Aquatic Displays in the Early Empire.” Journal of Roman Studies 83: 48–74.

Coleman, K. 2000. “Entertaining Rome.” In J. Coulston and H. Dodge, eds., 205–52.

Coleman, K., ed. 2006. M. Valerii Martialis Liber Spectaculorum. Oxford.

Colini, A. 1943. Stadium Domitiani. Rome.

Connolly, P. 2003. Colosseum: Rome’s Arena of Death. London.

Coulston, J. and H. Dodge, eds. 2000. Ancient Rome: The Archaeology of the Eternal City. Oxford.

Crowther, N. 2004. Athletika: Studies on the Olympic Games and Greek Athletics. Hildesheim.

Crummy, P. 2008a. “The Roman Circus at Colchester.” Britannia 39: 15–31.

Crummy, P. 2008b. “The Roman Circus at Colchester, England.” In J. Nelis-Clément and J.-M. Roddaz, eds., 213–31.

Dickison, S. and J. Hallett, eds. 2000. Rome and Her Monuments. Wauconda, IL.

Dodge, H. 2008. “Circuses in the Roman East: A Reappraisal.” In J. Nelis-Clémentand J.-M. Roddaz, eds., 133–46.

Dodge, H. 2009. “Amphitheaters in the Roman East.” In T. Wilmott, ed., 29–46.

Dodge, H. 2010. “Amusing the Masses: Buildings for Entertainment and Leisure in the Roman World.” In D. Potter and D. Mattingly, eds., 229–79.

Dodge, H. 2011. Spectacle in the Roman World. London.

Domergue, C., C. Landes, and J.-M. Pailler, eds. 1990. Spectacula, I: Gladiateurs et amphithéâtres. Paris.

Dunkle, R. 2008. Gladiators: Violence and Spectacle in Ancient Rome. Harlow, UK.

Gabucci, A., ed. 2001. The Colosseum. Translated by M. Becker. Los Angeles.

Gebhard, E. 1975. “Protective Devices in Roman Theaters.” In Ð. Mano-Zisi and J. Wiseman, eds., 43–63.

Golvin, J.-C. 1988. L’amphithéâtre romain: Essai sur la théorisation de sa forme et de ses fonctions. 2 vols. Paris.

Golvin, J.-C. 1990. “Les obélisques dressées sur la spina des grand cirques.” In C. Landes, V. Kramérovskis, and V. Fuentes, eds., 49–54.

Golvin, J.-C. and M. Reddé. 1990. “Naumachies, jeux nautiques et amphithéâtres.” In C. Domergue, C. Landes, and J.-M. Pailler, eds., 165–77.

Grainger, J. 2009. The Cities of Pamphylia. Oxford.

Green, J. and G. Stennett. 2002. “The Architecture of the Ancient Theatre at Nea Pafos.” Report of the Department of Antiquities, Cyprus: 155–88.

Humphrey, J. H. 1986. Roman Circuses: Arenas for Chariot Racing. Berkeley.

Humphrey, J. H. 1996. “Amphitheatrical Hippo-Stadia.” In A. Raban and K. Holum, eds., 121–9.

Humphrey, J. H., ed. 1999. The Roman and Byzantine Near East: Some Recent Archaeological Research, Volume 2. Ann Arbor.

Jennison, G. 1937. Animals for Show and Pleasure in Ancient Rome. Manchester.

König, J. 2005. Athletics and Literature in the Roman Empire. Cambridge.

Landes, C. and V. Kramérovskis, eds. 1992. Spectacula II: Le théâtre antique et ses spectacles. Lattes.

Landes, C., V. Kramérovskis, and V. Fuentes, eds. 1990. Le Cirque et les courses de chars Rome-Byzance. Lattes.

Lee, H. 2000. “Venues for Greek Athletics in Rome.” In S. Dickison and J. Hallett, eds., 215–40.

Mano-Zisi, Ð. and J. Wiseman, eds. 1975. Studies in the Antiquities of Stobi II. Belgrade.

Miller, S. 2001. Excavations at Nemea II: The Early Hellenistic Stadium. Berkeley.

Moretti, J.-C. 1992. “L’adaptation des théâtres de Gréce aux spectacles impèriaux.” In C. Landes and V. Kramérovskis, eds., 17–85.

Nelis-Clément, J. and J.-M. Roddaz, eds. 2008. Le cirque romain et son image: Actes du colloque tenu à l’Institut Ausonius, Bordeaux, 2006. Pessac.

Newby, Z. 2005. Greek Athletics in the Roman World: Victory and Virtue. Oxford.

Ostrasz, A. 1991. “The Excavation and Restoration of the Hippodrome at Jerash. A Synopsis.” Annual of the Department of Antiquities of Jordan 25: 23–50.

Ostrasz, A. 1995. “The Hippodrome of Gerasa: A Case of the Dichotomy of Art and Building Technology.” In K. Amr, F. Zayadine, and M. Zaghloul, eds., 183–92.

Parrish, D., ed. 2001. Urbanism in Western Asia Minor. Portsmouth, RI.

Potter, D. and D. Mattingly, eds. 2010. Life, Death, and Entertainment in the Roman Empire. 2nd ed. Ann Arbor.

Raban, A. and K. Holum, eds. 1996. Caesarea Maritima: A Retrospective after Two Millennia. Leiden.

Robert, L. 1940. Les gladiateurs dans l’Orient grec. Paris.

Romano, D. 2005. “A Roman Circus in Corinth.” Hesperia 74: 585–611.

Roueché, C. 1993. Performers and Partisans at Aphrodisias in the Roman and Late Roman Periods. London.

Scobie, A. 1988. “Spectator Security and Comfort at Gladiatorial Games.” Nikephoros 1: 192–243.

Sear, F. 2006. Roman Theatres: An Architectural Study. Oxford.

Simpson, C. 2000. “Musicians and the Arena: Dancers and the Hippodrome.” Latomus 59: 633–9.

Taylor, R. 2000. Public Needs and Private Pleasures: Water Distribution, the Tiber River and the Urban Development of Ancient Rome. Rome.

Traversari, G. 1960. Gli spettacoli in acqua nel teatro tardo-antico. Rome.

Vann, R. L. 1989. The Unexcavated Buildings of Sardis. Oxford.

Weiss, Z. 1996. “The Jews and the Games in Roman Caesarea.” In A. Raban and K. Holum, eds., 443–53.

Weiss, Z. 1999. “Adopting a Novelty: The Jews and the Roman Games in Palestine.” In J. H. Humphrey, ed., 23–49.

Welch, K. 1998a. “Greek Stadia and Roman Spectacles: Athens and the Tomb of Herodes Atticus.” Journal of Roman Archaeology 11: 117–45.

Welch, K. 1998b. “The Stadium at Aphrodisias.” American Journal of Archaeology 102: 547–69.

Welch, K. 1999. “Negotiating Roman Spectacle Architecture in the Greek World: Athens and Corinth.” In B. Bergmann and C. Kondoleon, eds., 125–45.

Wiedemann, T. 1992. Emperors and Gladiators. London.

Wilmott, T., ed. 2009. Roman Amphitheatres and Spectacula: A 21st-Century Perspective. Oxford.

GUIDE TO FURTHER READING

For helpful introductory surveys on the venues in which Roman spectacles were staged, see Coleman 2000 and Dodge 2010.

Humphrey 1986 remains the essential study of the Roman circus, unsurpassed in its details, accuracy, and interpretation of the remains. Nelis-Clément and Roddaz 2008 is an important recent collection of essays on the circus. On circuses beyond Rome, see Landes, Kramérovskis, and Fuentes 1990 on the Byzantine Empire; Ostrasz 1991 and 1995 on Jordan; Roueché 1993 and Welch 1998b on Aphrodisias; Weiss 1996 on Caesarea; Basarrate and Sánchez-Palencia 2001 on Spain; Romano 2005 on Corinth; and Crummy 2008a and b on Colchester.

On the art and people of the circus, see Chapter 33. Golvin 1990 discusses obelisks in circuses. On animals and the circus, see Chapter 34.

On facilities for Greek sport at Rome (e.g., stadia, baths), see Colini 1943; Lee 2000; Newby 2005; and Chapter 36.

On theaters and spectacles Landes and Kramérovskis 1992 is an essential reference work. On adaptations of theaters for Roman spectacles, see Gebhard 1975; Moretti 1992; Welch 1998a and 1999; and Humphrey 1996.

On artificial lakes used for staged naval battles, see Golvin and Reddé 1990; Coleman’s insightful 1993 essay; and the exhaustive study in Cariou 2009. On Late Imperial aquatic spectacles, Traversari 1960 remains the major work.