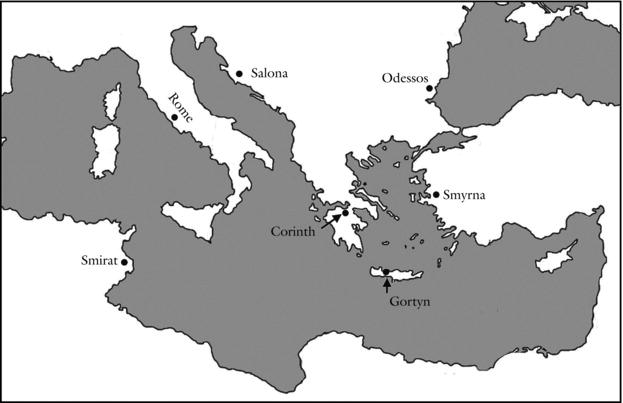

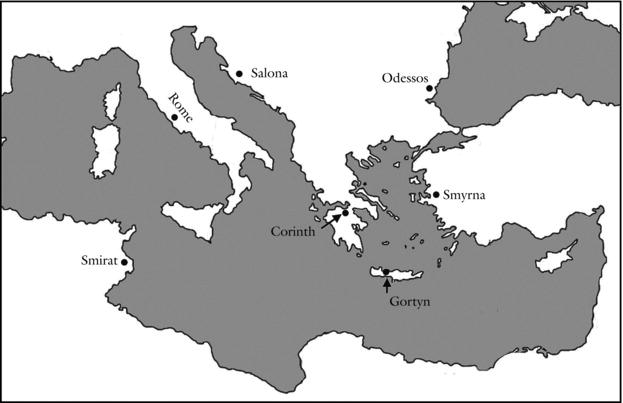

Map 42.1 Key sites mentioned in this essay.

In the spring of 227 CE, the people of Odessos, a Greek city in the Roman province of Moesia Inferior, were given expensive spectacles for their entertainment (see Map 42.1 for the locations of key sites mentioned in this essay). We know about these spectacles because a large, stone inscription announcing them still survives. The inscription provides the official reasons for the show, the date, and the identity of those paying for it. The stone was decorated with a series of reliefs depicting the show to come: gladiators, animals (mainly bulls), and beast hunters. Given the permanence of this stone announcement, it is probable that the inscription was meant not only to advertise the spectacles before they took place, but also to commemorate them long afterwards.

With good fortune! For the fortune and victory and eternal endurance of the most holy and great and unconquerable emperor Marcus Aurelius Severus Alexander, Pius, Felix, Augustus and for the fortune of Julia Mamaea the Augusta and their whole house and for the sacred Senate and people of Rome and for the sacred armies and for the illustrious Lucius Mantennius Sabinus the military governor and for the council and people of Odessos . . . the chief priests of the city, Marcus Aurelius Simon, son of Simon, the councilor, and Marcus Aurelius Io . . . [the stone is damaged] through beast-hunts and gladiatorial combats [. . . a certain number of . . .] days before the Kalends of May [or March, the stone is damaged] in the consulship of Albinus and Maximus.1 (Inscriptiones Graecae in Bulgaria repertae I.2: no. 70; Bulletin épigraphique 1972: no. 300)

What we see here was repeated in cities all over the Empire, including the ancient and sophisticated Greek cities around the Aegean Sea.

Map 42.1 Key sites mentioned in this essay.

Although gladiatorial combats had been exhibited in Rome from the mid-third century BCE and beast hunts (venationes in Latin, kunegesia in Greek) from at least the early second century BCE, their diffusion throughout the Empire, both East and West, was especially a phenomenon of the Imperial period (31 BCE–476 CE), in particular, the first to third centuries CE. By that time, a set of Roman games, known as a munus (plural munera), tended to include executions as well as venationes and gladiatorial combats (Ville 1981: 391–3).2

Just as at Odessos, most Roman spectacles in the provinces were closely connected with the celebration of the imperial cult, that is, the worship of the Roman emperor as a god.3 When a priest of the imperial cult came into office, he was expected to provide a munus.4

Because such spectacles seem so ostentatiously Roman, and because of their close association with the worship of the Roman emperor, it is tempting to link these shows with the deliberate projection of Roman power and influence into the provinces. Yet, there is no evidence that it was ever a policy of the emperors or the imperial administration to promote the spread of the Roman munus among their provincial subjects. Whereas emperors staged munera in Rome, maintained gladiatorial troupes, and could make both convicts and beasts available (presumably for a price) to be exhibited and killed in provincial shows (Dunkle 2008: 51–4, 173–90), they never compelled their provincial subjects to adopt the spectacles of the arena. Indeed, they were often willing to support requests to forego these expensive spectacles if other, more worthy, civic projects were needed (Coleman 2008). The connection with the imperial cult, moreover, probably points to local motivation rather than direction from Rome. In the eastern, Greek-speaking part of the Roman Empire, the imperial cult was a way for the Greeks themselves to translate the vast power of Rome into a local setting, either civic or provincial (Price 1984). However Roman these games at Odessos may appear, they were put on by Greeks, for Greeks, in a Greek ceremonial context.

The significance of all this is debated. While some scholars believe that the spread of these shows to the provinces indicates little more than a popular taste for bloodshed and exciting entertainment, most now argue that the shows point to broader cultural changes brought on by centuries of Roman rule (see, for example, Woolf 1994). Traditionally, scholarship has identified this process as “Romanization.” As a concept, however, Romanization has been controversial, primarily because it is rooted in outdated nineteenth-century European experiences of empire, which, it was thought, resulted in the spread of European institutions to what was seen as the less civilized colonies (Wallace-Hadrill 2008: 9–17). But no society simply adopts perfectly the ideas, practices, or institutions of another without first understanding them in terms of its own culture and then, perhaps, altering them to its own needs and expectations. The focus of study, therefore, should not be the (ostensible) imposition of cultural institutions, or even the assimilation of such institutions into a provincial context, but, rather, the effects that these institutions had on provincial – here Greek – culture and cultural identities.

Despite the difficulties that many see in defining “cultural identity” (Brubaker and Cooper 2000; Pitts 2007), it is possible to outline central features that are shared by different members participating in the group identity – what Greg Woolf refers to as “the parameters of discourse” (Woolf 1994: 118). In a similar way, Jonathan Hall observes that ethnic identities are “discursively constructed” from within by the participants themselves and not imposed from without (Hall 1997: 2). The mass public spectacles of the Greek and Roman world provided an ideal arena where such a discourse could take place.

A considerable and constantly growing body of evidence shows that audiences at spectacles staged in the eastern half of the Roman Empire closely engaged with the events they voluntarily attended. They were not passive recipients of Roman culture, but active consumers, and they shaped the spectacles they attended in ways that reflected their own cultural traditions. Roman spectacles in the Greek East were, therefore, mutually influential dialogues that involved a number of different groups including government officials, soldiers, and others from Rome itself; elite and nonelite local residents with varying degrees of exposure to Roman culture and allegiance to Rome; and, of course, the performers.5

Much of what we know about the popularity of Roman spectacles in the Greek provinces of the Empire is due to the work of Louis Robert. By assembling hundreds of inscriptions relating to the presentation of gladiatorial combats, spectacular executions, and beasts hunts in the Greek world, Robert demonstrated the degree to which the Greeks adopted these shows as their own. For Robert, the evident popularity of these Roman spectacles was “one of the successes of the Romanization of the Greek world.” Yet, he did not explore the significance of this beyond the observation that “Greek society had been infected by this sickness from Rome” (Robert 1940: 263).

In both the scholarly world and popular imagination there has long existed a sharp division between “sport” and “spectacle,” a division that splits the Greeks from the Romans. The Greeks gave the world sport, physical contests between athletes who competed for simple wreath crowns in order to display their excellence (arete). The Romans preferred worthless spectacle that pandered to the lowest, bloodiest tastes of the idle masses, and their emperors bought the loyalty of the populace with free food and mindless entertainments – Juvenal’s famous panem et circenses (“bread and circuses,” Satires 10.81). Sport is good; spectacle is bad.

All of this is tied up in modern stereotypes. Where “sport” conjures images of fitness and the active struggle for excellence, “spectacle” presents us with the negative: the passive observer being entertained by empty illusion, with an emphasis “on surface over content, on special effects that appeal to the senses, rather than on ideas engaging the intellect” (Bergmann 1999: 11).

But the sport/spectacle: Greek/Roman dichotomy is misleading. Right from the very beginning of Greek sport we find the presence of spectators to have been an integral element in athletic competitions. Without spectators to watch and applaud them the whole point of athletes competing against each other was lost (Scanlon 1983). This is evident in our earliest literary source for Greek sport, Homer, whose accounts of sporting events make clear that onlookers were expected. For example, when Odysseus visits Phaiakia, his hosts arrange a set of athletic competitions, and, as Homer describes it, all the best men of the Phaiakians went “to gaze at the contests” and “an endless multitude followed” (Odyssey 8.96–233). For Greeks of Homer’s time, and for a long period thereafter, visible participation in athletics was a sign of elite status (see Chapter 3). Later, one of the defining elements of the major agonistic festivals of Greece – the Olympian, then the Pythian, Nemean, and Isthmian Games – was the throngs of spectators they attracted (see Chapter 17).

Audiences at Roman spectacles were even more engaged than their counterparts at Greek sporting events. Cicero, writing in the first century BCE, saw that the political power of an audience in the theater and at the games equaled that of political assemblies (Cicero For Publius Sestius 106, 116). The political elite in Rome were more open to challenge in the theater, circus, and amphitheater than anywhere else. The people as a group were able to “talk back” to their political masters, even to the emperor or his designates during the Imperial period. They had the power to cheer or to deride (Parker 1999). David Potter has summed up the politicized character of Roman spectacles concisely: “Virtually every aspect of Roman hierarchy was open to challenge – public executions could go awry if the crowd demanded the release of the condemned, gladiators could become heroes, charioteers could become millionaires, and actors might challenge the order of society by the way they chose to utter their lines” (Potter 2006b: 385). (For further discussion of Roman spectacle as a site for dialogue between the masses and the elite, see Chapter 30.)

Moreover, it is important to keep in mind that ancient concepts of viewing were different from our own. Whereas we consider spectators to be passive observers of spectacles performed for them, the ancient Greeks and Romans had it the other way around. They were keenly aware that viewing was bidirectional: the viewer watched the viewed. Spectating was thus an active process, and the spectacle was the object of their gaze (Frilingos 2004: 15). The act of viewing meant that the assembled people were fundamentally involved in the spectacle and just as important to it as those performing, whether they were aristocratic athletes or servile gladiators. Because the spectators assembled together, they helped to create their community, and because they assembled in order to watch something that deeply mattered to them, space was created for debates about cultural values, social relationships, ethnicity, gender, even identity: Were the athletes Greek? Could women compete? Did they cheat? Would they give their life for victory? Indeed, the very act of spectating seems to have had a religious dimension to it, analogous to modern perceptions of pilgrimage. By visiting the great agonistic festivals, spectators represented their own city (the locus for their primary identity) and also participated in the broader Greek community (Rutherford 2000). In one real sense, the importance of the spectacle lay in the fact that the people gathered together to watch.6

While the theater or the circus could give voice to a gathering of people, it was while watching a munus that they had deliberate roles to play. As mentioned earlier, by the first century CE munera frequently involved more than simply gladiatorial combats; they typically also included beast hunts (as at Odessos for example) as well as executions and perhaps other forms of entertainment. Beast hunts usually took place in the morning, followed by (or including) executions around noon, and then gladiatorial combats in the afternoon (Ville 1981: 391–3). For example, in his fictional account of the gladiatorial combat at Amastris, Lucian describes what he and Sisinnes saw in the theater before the gladiators were introduced: “Having taken our seats, we first saw wild beasts brought down with spears and hunted by dogs, and set against men in chains, evil-doers, we reasoned. When in came the gladiators” (Lucian Toxaris 59).

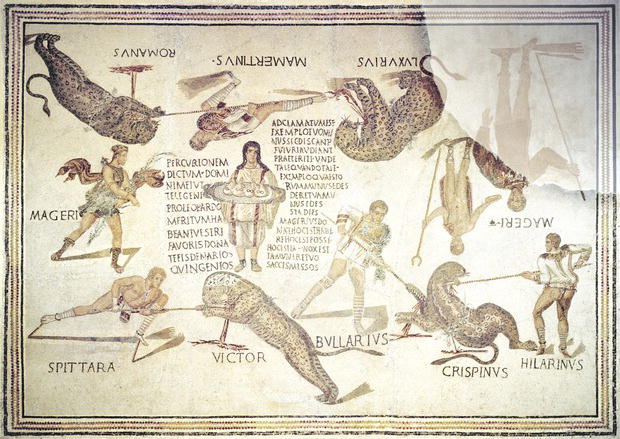

The people were not passive spectators being entertained by the animals that came before them. Instead they took an active role in the spectacle, either approving or disapproving of what was shown to them. For example, a mosaic from Smirat in North Africa that dates to the third century CE depicts and commemorates a venatio presented by a local magistrate named Magerius. The edges of the mosaic depict hunters slaying leopards in the arena; the central portion features a portrait of Magerius surrounded by a considerable amount of text (see Figure 42.1). Much of the text records the crowd’s response to a herald’s announcement of the generous rewards Magerius would offer to the hunters for their performance. The inscription probably captures what was actually shouted that day in the arena, and, because their phrases are metrical and repetitive (Hoc est habere! Hoc est posse!), it is possible that the audience shouted this sort of thing in unison:

The shout in reply: “May future generations know of your munus because you are an example for them; may past generations hear about it. Where has such a thing been heard before? When has such a thing been heard before? You have provided a munus as an example to the other magistrates. You have provided a munus from your own resources.” Magerius pays [the money]. “This is what it is to have money! This is what it is to have power! Now that it is evening, they have been dismissed from your munus with bags of money.”

It is probable that the people also shouted out Magerius’s name since the vocative form of his name – Mageri – appears twice on the mosaic as well.7

Figure 42.1 Mosaic from Smirat, Tunisia showing beast hunt and sponsor (Magerius), c.250 CE. Source: Vanni/Art Resource, NY.

The people clearly approved of Magerius’s exhibition, but there are examples where the people did not approve. One of the most famous comes to us from Rome. At the opening of the Theater of Pompey in Rome (55 BCE), it is reported that the sight of elephants being slaughtered at a venatio while apparently appealing for mercy roused the sympathy of the spectators and reflected badly on Pompey (Cicero Letters to His Friends 7.1.3; Pliny Natural History 8.20–1; Dio Cassius 39.38.2–3; cf. Bell 2004: 157–72; Shelton 1999 and 2004; and Chapter 34 in this volume).

Wild beasts, such as bears, bulls, and big cats, were also set against bound human victims, among whom Christians figured prominently. We have several accounts, called martyr acts, that recount such occurrences from a Christian perspective and that offer a unique view of events from the arena floor.

One of the things that stands out in these accounts is the active role of the crowd (Potter 1993). For example, in the middle of the second century CE at Smyrna in the province of Asia, a group of Christians was exposed to the beasts. A martyr act describes what happened:

For the most noble Germanicus strengthened the timidity of others by the perseverance that he showed, and he fought heroically with the wild beasts (etheriomachesen). For, when the proconsul8 sought to persuade him, and urged him to take pity upon his young age, he, with a show of force, dragged the beast on top of himself, being desirous to escape all the more quickly from this unjust and lawless world. But upon this the whole mob was astonished at the great nobility of mind displayed by the devout and godly race of the Christians. They cried out, “Away with the Atheists! Go get Polycarp!” (The Martyrdom of Polycarp 3.1–2)9

These events almost certainly took place during a munus celebrated by the provincial priest of the imperial cult, a certain Philip of Tralleis, who is mentioned in the text. The setting was especially suitable for executing Christians: one of the tests for early Christians facing execution was whether they would recant their religion and offer sacrifice to the Roman emperor as a god. The astonishment of the crowd is significant. While we must not lose sight of the fact that this piece was written by Christians for Christians, Germanicus is here presented as a sort of “star” in the arena, if only for a short time. Though some fellow Christians were too cowardly to fight and recanted, Germanicus made himself notable when he fought the beasts (etheriomachesen) so bravely. His performance amazed the people. For a moment he was like a famous beast hunter, imbued with the same power to astound the people as those beast hunters at Magerius’s show in Smirat. Amazement was a by-product of such shows (Frilingos 2004: 50–2).

One of the more remarkable facets of the sort of spectacle described above is the active participation of the crowd in meting out punishment (Potter 1993 and 1996: 147–55 and passim; cf. Thompson 2002). After Germanicus’s performance, the people called for Polycarp, the leader of the Christian community in Smyrna, and he was later arrested and brought before the crowd to be tried by the governor. The governor interrogating Polycarp commanded him to defend himself before the assembled people and, when he refused, threatened him with beasts and fire. Had Polycarp been able (or desired) to convince them, the people could presumably have requested his release (Potter 1996: 157). After his interrogation failed to convince Polycarp to sacrifice to the emperor, the governor ordered his herald to announce three times that Polycarp had confessed that he was a Christian. This incited the mob first to call on Philip to turn a lion lose on Polycarp, and when he declined (because of a legal technicality: the munus had ended), to demand that Polycarp be incinerated, which he then was (The Martyrdom of Polycarp 12.2–3).

Audiences at Roman spectacles seem to have regularly exercised agency of this sort. At about the same time that Polycarp was active in Smyrna, Fronto wrote to the future emperor Marcus Aurelius to advise him to heed the power of the people at spectacles:

Be prepared, when you speak before an assembly of men, to study their taste . . . And when you do so, remind yourself that you are but doing the same as you do when, at the people’s request [populo postulante], you honor or free those who have slain beasts manfully in the arena, even though they are murderers or condemned for some crime, you release them at the people’s request [populo postulante]. Everywhere then the people dominate and prevail. (To the Caesar Marcus 1.8, trans. C. Haines slightly modified)

Apuleius, writing in the second century CE, provides an account of a munus in Corinth that, though fictional, seems to reflect accurately a fairly typical spectacle. The munus includes a woman who had been convicted for murder and sentenced to public execution in the arena. Apuleius notes that before the condemned murderess was to be lead out to be bestially raped and killed, a soldier emerged to introduce the condemned women iam populo postulante – “at the people’s request” (Metamorphoses 10.34).

The key point for us is that these spectacles were legal executions – the fulfillment of a sentence handed down by a Roman court (Potter 1993). Though local courts were maintained in the provinces, only Roman courts held jurisdiction over penal or criminal matters and only Roman courts could pronounce capital punishment on freemen (Brélaz 2008). Though arrested by local officials, Polycarp was notably interrogated and sentenced by the proconsul (the chief Roman magistrate in the province); only he had the authority to do so.

By witnessing and participating in the spectacle, by applauding what happened there, perhaps even by demanding that it happen in the first place, the assembled people demonstrably approved not only of the execution of various convicts, but also of the whole process and structure that brought the spectacular execution about. The people’s appreciation at seeing Germanicus’s amazing fight translated into approval of the authorities. They were actively supporting a spectacle in which a Roman governor dispensed Roman justice in connection with a celebration of the Roman emperor as a god.

There may be more to this. The munus itself held deeper symbolic significance, for Romans at least. Venationes could be seen to celebrate the triumph of Roman civilization over the hostile natural world, spectacular executions to celebrate the triumph of Roman justice over those who opposed or rejected Roman civilization (Wiedemann 1992: 46). Did provincial Greek spectators see it this way too? The spectacle invested the people with real power and laid the ruling structure of the Empire open to challenge. Sympathy for the wild beasts meant disapproval of the civilizing emperor and army who eliminated them or kept them at bay; disapproval or rejection of the death of a convict meant rejection of the justice system that had convicted him or her. Reject the show, reject those who produced it.

On the other hand, acceptance and approval of the spectacle meant much more than just appreciation for seeing beasts and criminals killed. It meant an approbation and reaffirmation of the entire ruling structure that had made it possible. That ruling structure was not only Roman, but included the necessary cooperation of the local elites as well. Polycarp, for example, was arrested by local officials (the irenarchs or “keepers of the peace”), not the Roman army, and the shows were presented by local Greek priests of the imperial cult, not the Roman governor. A reexamination of our invitation from Odessos, with which we started the chapter, reveals that the shows – gladiatorial combats and wild beast hunts – were put on not only to celebrate the reigning emperor, Severus Alexander, but indeed for the benefit of the entire ruling structure of the Empire, from the emperor at the top, to the imperial household, to the Senate and people of Rome, to the armies, to the governor, right down to the local council and people.

In most cases a munus culminated with the presentation of gladiatorial combats. There is much evidence to indicate that these were not necessarily fights to the death and that gladiators in most cases escaped with their lives. Gladiatorial combats were fought according to strict rules enforced by a referee (the summa rudis), who was present in the arena with the fighters (Carter 2006/7). Of course, gladiatorial combats were dangerous and could result in death, but so too could traditional Greek combat sports: boxing, wrestling, and pankration (Scanlon 2002: 299–322). Georges Ville has calculated that the chances of a gladiator dying in any given bout were roughly 1 in 10 (Ville 1981: 318–25). Indeed, ordinary fights were not even fought with sharp weapons (Carter 2006). We hear of gladiatorial combats that were required to be fought to the death, but they seem to have been exceptional and might even have required permission from the imperial authorities (Dunkle 2008: 136–7).

If a gladiator were wounded he could request missio (release), usually by raising his hand or a finger, a gesture also found in Greek athletics (Miller 2004: 56). Gladiators were said to fight ad digitum (“to the finger”). The summa rudis then intervened to separate the combatants, a scene often seen in depictions of the gladiatorial combat (see Figure 31.2). At that point the defeated gladiator could either be granted missio or condemned to immediate execution. The decision was made by the person responsible for organizing the games in question, the editor, who consulted with the crowd over each such decision and was expected to adhere to its wishes (Dunkle 2008: 130–40). For Ville, those moments when the decisions to grant or deny missio or even to grant freedom were made marked the climax of the whole spectacle (Ville 1981: 424; cf. Flaig 2007: 87). Here again, we see spectators playing an active role.

Victorious gladiators could expect substantial rewards, including in some instances their freedom. Many, probably most, gladiators ended up on the arena floor involuntarily; they were prisoners of war or condemned criminals who entered gladiatorial training under compulsion (Dunkle 2008: 30–8). However, as is clear in a rescript from the emperor Hadrian, all gladiators, even those who had been criminally condemned, had the opportunity to win their freedom if they survived (Mosaicarum et Romanarum Legum Collatio 11.7, citing Ulpian). Perhaps the people also had the power to give freedom to a gladiator. For example, an epitaph from Salona in what is now Croatia commemorates a deceased gladiator, who had been granted freedom from the arena: “To the Immortal Shades. For the civilian man, Thelonicus, once a retiarius who was freed with the rudis by the piety of the people, Xustus his friend and Pepticius his comrade erected this”10 (Année Epigraphique 1934: no. 284).

All of this suggests that the gladiatorial combats were about something other than homicide. People did not come to see gladiators butchered; there was plenty of butchery in the executions that typically preceded the gladiators’ appearance on the floor of the arena. What they did come to see were duels between trained competitors, in which courage, martial skill, and discipline were put on display.

Gladiators embodied the fundamental Roman value of virtus (Wiedemann 1992: 35–8), which was more aggressive than simple “courage” and was gauged by behavior rather than assumed as a mindset (Harris 2006; Rosenstein 2006). There was a strong inclination among both editores and audiences to spare the lives of gladiators who displayed virtus. Thus the munus was in some ways a celebration of this key Roman value.

Egon Flaig has persuasively argued that the willingness of non-Roman provincials, such as the Greeks, to participate in this process of granting missio indicates “a desire of provincial populations to integrate themselves into the Roman culture of bravery and military values. Those who accepted gladiatorial combat as a part of cultural life accepted the framework of Roman virtues and their celebration” (Flaig 2007: 86). This profound observation gives force to the idea that gladiatorial combats had a Romanizing impact, altering the values of provincial cultures.

This dynamic may well have played itself out differently in different parts of the Empire because whereas gladiators in the western provinces tended to liken themselves to soldiers (Hope 2000), in the eastern part of the Roman world they perceived and presented themselves as athletic heroes. Their tombstones and other monuments evoke images of heroic and athletic victors (Golden 2008: 68–104; Mann 2009).

This merging of gladiators and athletes built upon long-standing traditions in Greek culture. The values celebrated in gladiatorial combat – excellence in ostentatious single combat – are essentially the same as those at the heart of Greek athletics. As early as the Archaic period (700–480 BCE) in Greek history, the heroic champions of earlier days had been replaced by a new military formation – the hoplite phalanx. The battlefield was no longer the place for individual acts of courage and honor of the sort that had been celebrated by Homer. Indeed, such individualistic values were discouraged in war in favor of the corporate discipline and courage demanded by hoplite warfare. No longer as important on the battlefield, the old aristocratic values celebrating individual honor and victory in single combat were removed to the gymnasion and to the competitive athletics of the great athletic festivals (Müller 1995: 115–25; though cf. Christesen 2007: 60 and passim). This agonistic spirit, which had its roots in the Greek heroic age, maintained much of its martial origins into later Greek history. For example, an epitaph found at Olympia and dating to the third century CE reads, “He died here, boxing in the stadium, having prayed to Zeus for victory or death” (Supplementum Epigraphicum Graecum 22.354, trans. M. Poliakoff). The ideology of both athletes and gladiators was rooted in the same martial principles: ostentatious victory or death. Athletic self-presentation by gladiators thus made immediate sense and was entirely recognizable to Greeks (Carter 2009).

It is possible that the spectacle was an important bridge between the cultural worlds of the Greeks and Romans. But it might also have been a focus for a debate concerning what was Greek and what was Roman. This, it seems to me, is the key element in what we might now think of as Romanization. Far from being empty illusions entertaining passive spectators, the grand public spectacles of the Greek and Roman world were dynamic events that gave an active role to the gathered people. This is especially true of the Roman munus, which was in many ways a spectacle putting the whole ruling structure of the Empire on the line: cheers indicated approval of the capture and slaughter of dangerous beasts by Roman power, the execution of criminals by Roman authorities, and the martial virtue of the gladiators. This last one was especially significant since the gladiatorial combats in particular presented Greek spectators with an ideology completely familiar to them and at the heart of athletic values fundamental to Greek self-definition. In many ways, gladiators were athletes par excellence. A gladiator from Gortyn on Crete perhaps said it best: “The olive is not the prize; we fight for our lives!” (Robert 1940: no. 66). Was the Roman so alien after all?

NOTES

1 All translations of Greek and Latin texts presented here, unless otherwise indicated, are my own.

2 Munus originally meant “duty” or “gift.” It gradually came to be used for both spectacles in general and gladiatorial games in particular, with the latter meaning becoming the more dominant one over the course of time. See Ville 1981: 72–8.

3 On the connection between imperial cult and spectacle in the Roman world, see Dodge 2009; Fishwick 1987–2005: vol. 1.1: 97–137, vol. 3.3: 305–50; and Futrell 1997: 79–93. On gladiatorial combats, see Chapters 25, 30, 31, and 32 in this volume. On beast hunts and public executions, see Chapters 34 and 35 respectively.

4 Newly appointed imperial priests thus had a sudden need for animals and a host of personnel. One way of dealing with this logistical problem was to lease gladiators and the requisite support staff (referees, trainers, etc.). In many provinces, such as Asia, however, it was common for priests to own their own troupes, buying them from the previous priest and selling them to their successors in office. Some of these troupes are known to have included not only gladiators, but also convicts, presumably awaiting execution during a show. It is probable that the convicts were purchased from the imperial government (Carter 2003).

5 A similar process played itself out in the western half of the Roman Empire, but with enough differences as to make it necessary to focus here largely on the eastern part of the empire.

6 There is an extensive body of scholarly literature on the effects of spectating, particularly in large groups. The foundational work on this subject was done by Durkheim in the early part of the twentieth century (Durkheim 2001 (1912)). Insights from Durkheim and his many successors have been fruitfully applied to the study of Roman spectacle by a number of important works, most recently in Fagan 2011: 189–229.

7 On the Magerius mosaic, see Beschaouch 1966; Blanchard-Lemée, Ennaïfer, Slim, et al. 1996 (1995): 209–14 and fig. 162; Dunbabin 1978: 67–70 and figs. 52–3; Brown 1992: 198–200; Potter 1996: 129–30; Bomgardner 2009; and Fagan 2011: 128–32. On the text on the mosaic, see Année Epigraphique 1967: no. 549. The interpretation of the text on the mosaic presents a number of challenges, most notably whether it should be read in two sections or three. The basic sense of the text is, however, clear.

8 A proconsul was the chief Roman magistrate in a province.

9 A (seemingly paradoxical) charge frequently leveled against Christians during this period was that they were atheists; see the discussion in Chapter 41. Polycarp was the leader of the Christian community in Smyrna. The key source for this event is the Martyrdom of Polycarp, on which see Frilingos 2004: 116–19 and Musurillo 1972: xiii–xvi, 2–37. (The latter provides an English translation.)

10 The rudis was a wooden staff that was awarded to a gladiator to symbolize his permanent release. A retiarius was a type of gladiator that fought with a trident and net (Dunkle 2008: 71, 107–11).

REFERENCES

Barchiesi, A. and W. Scheidel, eds. 2010. The Oxford Handbook of Roman Studies. Oxford.

Bell, A. 2004. Spectacular Power in the Greek and Roman City. Oxford.

Bergmann, B. 1999.“Introduction The Art of Ancient Spectacle.” In B. Bergmann and C. Kondoleon, eds., 9–35.

Bergmann, B. and C. Kondoleon, eds. 1999. The Art of Ancient Spectacle. New Haven.

Beschaouch, A. 1966. “La mosaïque de chasse à l’amphithéâtre découverte à Smirat en Tunisie.” Comptes rendus de l’Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres: 134–57.

Blanchard-Lemée, M., M. Ennaïfer, H. Slim, et al. 1996 (1995). Mosaics of Roman Africa. Translated by K. Whitehead. New York.

Bomgardner, D. 2009. “The Magerius Mosaic Revisited.” In T. Wilmott, ed., 165–78.

Brélaz, C. 2008. “Maintaining Order and Exercising Justice in the Roman Provinces of Asia Minor.” In B. Forsén and G. Salmeri, eds., 45–64.

Brown, S. 1992. “Death as Decoration: Scenes from the Arena on Roman Domestic Mosaics.” In A. Richlin, ed., 180–211.

Brubaker, R. and F. Cooper. 2000. “Beyond ‘Identity.’” Theory and Society 29: 1–47.

Byrne, S. and E. Cueva, eds. 1999. Veritatis Amicitiaeque Causa: Essays in Honor of Anna Lydia Motto and John R. Clark. Wauconda, IL.

Carter, M. 2003. “Gladiatorial Ranking and the SC de Pretiis Gladiatorum Minuendis (CIL II 6278=ILS 5163).” Phoenix 57: 83–114.

Carter, M. 2006a. “Gladiatorial Combat with ‘Sharp’ Weapons (tois oxesi siderois).” Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik 155: 161–75.

Carter, M. 2006b. “Gladiatoral Combat: The Rules of Engagement.” The Classical Journal 102: 97–114.

Carter, M. 2009. “Gladiators and Monomachoi: Greek Attitudes to a Roman ‘Cultural Performance.’” International Journal of the History of Sport 26: 298–322.

Christesen, P. 2007. “The Transformation of Athletics in Sixth-Century Greece.” In G. Schaus and S. Wenn, eds., 59–68.

Coleman, K. 2008. “Exchanging Gladiators for an Aqueduct at Aphrodisias (SEG 50.1096).” Acta Classica 51: 31–46.

Coleman, K. 2010. “Spectacle.” In A. Barchiesi and W. Scheidel, eds., 651–70.

Cooley, A., ed. 2000. The Epigraphic Landscape of Roman Italy. London.

Dillon, S. and K. Welch, eds. 2006. Representations of War in Ancient Rome. Cambridge.

Dodge, H. 2009. “Amphitheaters in the Roman East.” In T. Wilmott, ed., 29–46.

Dunbabin, K. 1978. The Mosaics of Roman North Africa: Studies in Iconography and Patronage. Oxford.

Dunkle, R. 2008. Gladiators: Violence and Spectacle in Ancient Rome. Harlow, UK.

Durkheim, É. 2001 (1912). The Elementary Forms of Religious Life. Translated by C. Cosman. Oxford.

Fagan, G. 2011. The Lure of the Arena: Social Psychology and the Crowd at the Roman Games. Cambridge.

Fishwick, D. 1987–2005. The Imperial Cult in the Latin West: Studies in the Ruler Cult of the Western Provinces of the Roman Empire. 4 vols. Leiden.

Flaig, E. 2007. “Gladiatorial Games: Ritual and Political Consensus.” In R. Roth and J. Keller, eds., 83–92.

Forsén, B. and G. Salmeri, eds. 2008. The Province Strikes Back: Imperial Dynamics in the Eastern Mediterranean. Helsinki.

Frilingos, C. 2004. Spectacles of Empire: Monsters, Martyrs, and the Book of Revelation. Philadelphia.

Futrell, A. 1997. Blood in the Arena: The Spectacle of Roman Power. Austin, TX.

Golden, M. 2008. Greek Sport and Social Status. Austin, TX.

Hall, J. M. 1997. Ethnic Identity in Greek Antiquity. Cambridge.

Harris, W. 2006. “Readings in the Narrative Literature of Roman Courage.” In S. Dillon and K. Welch, eds., 301–20.

Hope, V. 2000. “Fighting for Identity: The Funerary Commemoration of Italian Gladiators.” In A. Cooley, ed., 93–113.

Joyal, M. and R. Egan, eds. 2004. Daimonopylai: Essays in Classics and the Classical Tradition Presented to Edmund G. Berry. Winnipeg.

Kyle, D. 2007. Sport and Spectacle in the Ancient World. Malden, MA.

Mann, C. 2009. “Gladiators in the Greek East: A Case Study in Romanization.” International Journal of the History of Sport 26: 272–97.

Miller, S. 2004. Ancient Greek Athletics. New Haven.

Müller, S. 1995. Das Volk der Athleten: Untersuchungen zur Ideologie und Kritik des Sports in der griechisch-römischen Antike. Trier.

Musurillo, H. 1972. The Acts of the Christian Martyrs. Oxford.

Parker, H. 1999. “The Observed of All Observers: Spectacle, Applause, and Cultural Poetics in the Roman Audience.” In B. Bergmann and C. Kondoleon, eds., 163–79.

Pitts, M. 2007. “The Emperor’s New Clothes? The Utility of Identity in Roman Archaeology.” American Journal of Archaeology 111: 693–713.

Potter, D. 1993. “Martyrdom as Spectacle.” In R. Scodel, ed., 53–88.

Potter, D. 1996. “Performance, Power, and Justice in the High Empire.” In W. Slater, ed., 129–60.

Potter, D., ed. 2006a. A Companion to the Roman Empire. Malden, MA.

Potter, D. 2006b. “Spectacle.” In D. Potter, ed., 385–408.

Potter, D. 2012. The Victor’s Crown: A History of Ancient Sport from Homer to Byzantium. Oxford.

Price, S. R. F. 1984. Rituals and Power: The Roman Imperial Cult in Asia Minor. Cambridge.

Richlin, A., ed. 1992. Pornography and Representation in Greece and Rome. New York.

Robert, L. 1940. Les gladiateurs dans l’Orient grec. Paris.

Rosenstein, N. 2006. “Aristocratic Values.” In N. Rosenstein and R. Morstein-Marx, eds., 365–82.

Rosenstein, N. and R. Morstein-Marx, eds. 2006. A Companion to the Roman Republic. Malden, MA.

Roth, R. and J. Keller, eds. 2007. Roman by Integration: Dimensions of Group Identity in Material Culture and Text. Portsmouth, RI.

Rutherford, I. 2000. “Theoria and Darsan: Pilgrimage and Vision in Greece and India.” Classical Quarterly 50: 133–46.

Scanlon, T. 1983. “The Vocabulary of Competition: Agôn and Aethlos, Greek Terms for Contest.” Arete 1: 147–62.

Scanlon, T. 2002. Eros and Greek Athletics. Oxford.

Schaus, G. and S. Wenn, eds. 2007. Onward to the Olympics: Historical Perspectives on the Olympic Games. Waterloo, ON.

Scodel, R., ed. 1993. Theater and Society in the Classical World. Ann Arbor.

Shelton, J.-A. 1999. “Elephants, Pompey, and the Reports of Popular Displeasure in 55 BC.” In S. Byrne and E. Cueva, eds., 231–71.

Shelton, J.-A. 2004. “Dancing and Dying: The Display of Elephants in Ancient Roman Arenas.” In M. Joyal and R. Egan, eds., 363–82.

Slater, W., ed. 1996. Roman Theater and Society. Ann Arbor.

Thompson, L. 2002. “The Martyrdom of Polycarp: Death in the Roman Games.” Journal of Religion 82: 27–52.

Veyne, P. 1990. Bread and Circuses: Historical Sociology and Political Pluralism. Translated by B. Pearce. London.

Ville, G. 1981. La gladiature en Occident, des origines à la mort de Domitien. Rome.

Wallace-Hadrill, A. 2008. Rome’s Cultural Revolution. Cambridge.

Wiedemann, T. 1992. Emperors and Gladiators. London.

Wilmott, T., ed. 2009. Roman Amphitheatres and Spectacula: A 21st-Century Perspective. Oxford.

Woolf, G. 1994. “Becoming Roman, Staying Greek: Culture, Identity and the Civilizing Process in the Roman East.” Proceedings of the Cambridge Philological Society 40: 116–43.

Yavetz, Z. 1969. Plebs and Princeps. London.

GUIDE TO FURTHER READING

The debate about Romanization is ongoing, but useful summaries can be found in Woolf 1994; Wallace-Hadrill 2008; and Mann 2009. The idea of spectacle is tackled by leading scholars in Bergmann and Kondoleon 1999 and more recently by Potter 2006b and Coleman 2010. Also recently, Kyle 2007 and Potter 2012 have each brought together sport and spectacle into a single analysis.

For audience involvement in spectacles, two good starting places are Chapter 30 in the present volume and Potter 1996; see also Yavetz 1969; Veyne 1990: 292–482; and Parker 1999. Potter’s 1993 study of the relationship between martyrdom and spectacle is also essential. Translation of key texts from among the martyr acts can be found in Musurillo 1972. Frilingos 2004 directs our understanding of ancient spectacle toward an interpretation of the Book of Revelation. On gladiators, beast hunts, and spectacular executions, see in this volume, Chapters 31, 32, 34, and 35. For gladiators in the Greek world (with specific bibliography), see Robert 1940; Golden 2008: 68–104; Mann 2009; and Carter 2009.