Chapter 3. Exponents, Roots, and Factorization of Whole Numbers

3.1. Objectives*

After completing this chapter, you should

Exponents and Roots (Section 3.2)

understand and be able to read exponential notation

understand the concept of root and be able to read root notation

be able to use a calculator having the yx key to determine a root

Grouping Symbols and the Order of Operations (Section 3.3)

understand the use of grouping symbols

understand and be able to use the order of operations

use the calculator to determine the value of a numerical expression

Prime Factorization of Natural Numbers (Section 3.4)

be able to determine the factors of a whole number

be able to distinguish between prime and composite numbers

be familiar with the fundamental principle of arithmetic

be able to find the prime factorization of a whole number

The Greatest Common Factor (Section 3.5)

be able to find the greatest common factor of two or more whole numbers

The Least Common Multiple (Section 3.6)

be able to find the least common multiple of two or more whole numbers

3.2. Exponents and Roots *

Section Overview

Exponential Notation

Reading Exponential Notation

Roots

Reading Root Notation

Calculators

Exponential Notation

We have noted that multiplication is a description of repeated addition. Exponential notation is a description of repeated multiplication.

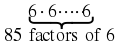

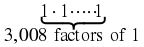

Suppose we have the repeated multiplication

8 ⋅ 8 ⋅ 8 ⋅ 8 ⋅ 8

The factor 8 is repeated 5 times. Exponential notation uses a superscript for the number of times the factor is repeated. The superscript is placed on the repeated factor, 8 5 , in this case. The superscript is called an exponent.

An exponent records the number of identical factors that are repeated in a multiplication.

Sample Set A

Write the following multiplication using exponents.

Example 3.1.

3⋅3. Since the factor 3 appears 2 times, we record this as

32

Example 3.2.

62⋅62⋅62⋅62⋅62⋅62⋅62⋅62⋅62. Since the factor 62 appears 9 times, we record this as

629

Expand (write without exponents) each number.

Example 3.3.

124 . The exponent 4 is recording 4 factors of 12 in a multiplication. Thus,

124 = 12⋅12⋅12⋅12

Example 3.4.

7063 . The exponent 3 is recording 3 factors of 706 in a multiplication. Thus,

7063 = 706⋅706⋅706

Practice Set A

Write the following using exponents.

Write each number without exponents.

Reading Exponential Notation

In a number such as 85 ,

8 is called the base.

5 is called the exponent, or power. 85 is read as "eight to the fifth power," or more simply as "eight to the fifth," or "the fifth power of eight."

When a whole number is raised to the second power, it is said to be squared. The number 52 can be read as

5 to the second power, or 5 to the second, or 5 squared.

When a whole number is raised to the third power, it is said to be cubed. The number 53 can be read as

5 to the third power, or 5 to the third, or 5 cubed.

When a whole number is raised to the power of 4 or higher, we simply say that that number is raised to that particular power. The number 58 can be read as

5 to the eighth power, or just 5 to the eighth.

Roots

In the English language, the word "root" can mean a source of something. In mathematical terms, the word "root" is used to indicate that one number is the source of another number through repeated multiplication.

We know that 49 = 72 , that is, 49 = 7⋅7. Through repeated multiplication, 7 is the source of 49. Thus, 7 is a root of 49. Since two 7's must be multiplied together to produce 49, the 7 is called the second or square root of 49.

We know that 8 = 23 , that is, 8 = 2⋅2⋅2. Through repeated multiplication, 2 is the source of 8. Thus, 2 is a root of 8. Since three 2's must be multiplied together to produce 8, 2 is called the third or cube root of 8.

We can continue this way to see such roots as fourth roots, fifth roots, sixth roots, and so on.

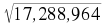

Reading Root Notation

There is a symbol used to indicate roots of a number. It is called the radical sign

The symbol

is called a radical sign and indicates the nth root of a number.

is called a radical sign and indicates the nth root of a number.

We discuss particular roots using the radical sign as follows:

indicates the square root of the number under the radical sign. It is customary to drop the 2 in the radical sign when discussing square roots. The symbol

indicates the square root of the number under the radical sign. It is customary to drop the 2 in the radical sign when discussing square roots. The symbol

is understood to be the square root radical sign.

is understood to be the square root radical sign.

= 7 since

7⋅7 = 72 = 49

= 7 since

7⋅7 = 72 = 49

indicates the cube root of the number under the radical sign.

indicates the cube root of the number under the radical sign.

since

2⋅2⋅2 = 23 = 8

since

2⋅2⋅2 = 23 = 8

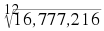

indicates the fourth root of the number under the radical sign.

indicates the fourth root of the number under the radical sign.

since

3⋅3⋅3⋅3 = 34 = 81

since

3⋅3⋅3⋅3 = 34 = 81

In an expression such as

is called the radical sign.

is called the radical sign.

5 is called the index. (The index describes the indicated root.)

32 is called the radicand.

is called a radical (or radical expression).

is called a radical (or radical expression).

Sample Set B

Find each root.

Example 3.5.

To determine the square root of 25, we ask, "What whole number squared equals 25?" From our experience with multiplication, we know this number to be 5. Thus,

To determine the square root of 25, we ask, "What whole number squared equals 25?" From our experience with multiplication, we know this number to be 5. Thus,

Check: 5 ⋅ 5 = 5 2 = 25

Example 3.6.

To determine the fifth root of 32, we ask, "What whole number raised to the fifth power equals 32?" This number is 2.

To determine the fifth root of 32, we ask, "What whole number raised to the fifth power equals 32?" This number is 2.

Check: 2 ⋅ 2 ⋅ 2 ⋅ 2 ⋅ 2 = 2 5 = 32

Practice Set B

Find the following roots using only a knowledge of multiplication.

Calculators

Calculators with the

,

y

x

, and

1 / x

keys can be used to find or approximate roots.

,

y

x

, and

1 / x

keys can be used to find or approximate roots.

Sample Set C

Example 3.7.

Use the calculator to find

| Display Reads | ||

| Type | 121 | 121 |

| Press |

| 11 |

Example 3.8.

Find

.

.

| Display Reads | ||

| Type | 2187 | 2187 |

| Press | y x | 2187 |

| Type | 7 | 7 |

| Press | 1 / x | .14285714 |

| Press | = | 3 |

(Which means that

37

=

2187

.)

(Which means that

37

=

2187

.)

Practice Set C

Use a calculator to find the following roots.

Exercises

For the following problems, write the expressions using exponential notation.

Exercise 3.2.16.

12⋅12

Exercise 3.2.18.

10⋅10⋅10⋅10⋅10⋅10

Exercise 3.2.20.

3,021⋅3,021⋅3,021⋅3,021⋅3,021

Exercise 3.2.22.

For the following problems, expand the terms. (Do not find the actual value.)

Exercise 3.2.24.

53

Exercise 3.2.26.

152

Exercise 3.2.28.

616

For the following problems, determine the value of each of the powers. Use a calculator to check each result.

Exercise 3.2.30.

32

Exercise 3.2.32.

12

Exercise 3.2.34.

112

Exercise 3.2.36.

132

Exercise 3.2.38.

14

Exercise 3.2.40.

73

Exercise 3.2.42.

1002

Exercise 3.2.44.

55

Exercise 3.2.46.

62

Exercise 3.2.48.

128

Exercise 3.2.50.

05

Exercise 3.2.52.

58

Exercise 3.2.54.

253

Exercise 3.2.56.

313

Exercise 3.2.58.

220

For the following problems, find the roots (using your knowledge of multiplication). Use a calculator to check each result.

Exercise 3.2.60.

Exercise 3.2.62.

Exercise 3.2.64.

Exercise 3.2.66.

Exercise 3.2.68.

Exercise 3.2.70.

Exercise 3.2.72.

Exercise 3.2.74.

Exercise 3.2.76.

For the following problems, use a calculator with the keys

,

y

x

, and

1 / x

to find each of the values.

,

y

x

, and

1 / x

to find each of the values.

Exercise 3.2.78.

Exercise 3.2.80.

Exercise 3.2.82.

Exercise 3.2.84.

Exercise 3.2.86.

Exercise 3.2.88.

Exercises for Review

Exercise 3.2.90.

(Section 1.7) Use the numbers 3, 8, and 9 to illustrate the associative property of addition.

Exercise 3.2.91. (Go to Solution)

(Section 2.2) In the multiplication 8⋅4 = 32, specify the name given to the numbers 8 and 4.

Exercise 3.2.94.

(Section 2.6) Use the numbers 4 and 7 to illustrate the commutative property of multiplication.

Solutions to Exercises

3.3. Grouping Symbols and the Order of Operations *

Section Overview

Grouping Symbols

Multiple Grouping Symbols

The Order of Operations

Calculators

Grouping Symbols

Grouping symbols are used to indicate that a particular collection of numbers and meaningful operations are to be grouped together and considered as one number. The grouping symbols commonly used in mathematics are the following:

Parentheses: ( ) Brackets: [ ] Braces: { } Bar: ___

In a computation in which more than one operation is involved, grouping symbols indicate which operation to perform first. If possible, we perform operations inside grouping symbols first.

Sample Set A

If possible, determine the value of each of the following.

Example 3.9.

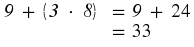

9 + ( 3 ⋅ 8 )

Since 3 and 8 are within parentheses, they are to be combined first.

Thus,

9 + ( 3 ⋅ 8 ) = 33

Example 3.10.

( 10 ÷ 0 ) ⋅ 6

Since 10÷0 is undefined, this operation is meaningless, and we attach no value to it. We write, "undefined."

Practice Set A

If possible, determine the value of each of the following.

Multiple Grouping Symbols

When a set of grouping symbols occurs inside another set of grouping symbols, we perform the operations within the innermost set first.

Sample Set B

Determine the value of each of the following.

Example 3.11.

2 + ( 8 ⋅ 3 ) − ( 5 + 6 )

Combine 8 and 3 first, then combine 5 and 6.

Example 3.12.

10 + [ 30 − ( 2 ⋅ 9 ) ]

Combine 2 and 9 since they occur in the innermost set of parentheses.

Practice Set B

Determine the value of each of the following.

The Order of Operations

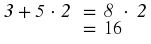

Sometimes there are no grouping symbols indicating which operations to perform first. For example, suppose we wish to find the value of 3 + 5⋅2. We could do either of two things:

Add 3 and 5, then multiply this sum by 2.

Multiply 5 and 2, then add 3 to this product.

We now have two values for one number. To determine the correct value, we must use the accepted order of operations.

Order of Operations

Perform all operations inside grouping symbols, beginning with the innermost set, in the order 2, 3, 4 described below,

Perform all exponential and root operations.

Perform all multiplications and divisions, moving left to right.

Perform all additions and subtractions, moving left to right.

Sample Set C

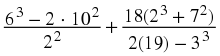

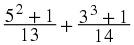

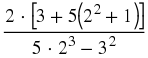

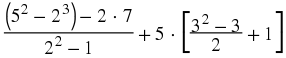

Determine the value of each of the following.

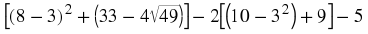

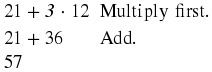

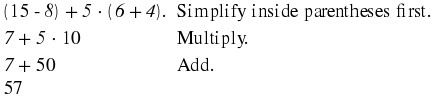

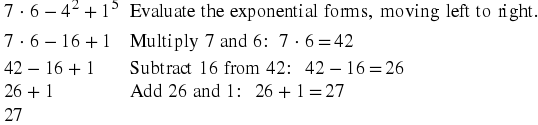

Example 3.13.

Example 3.14.

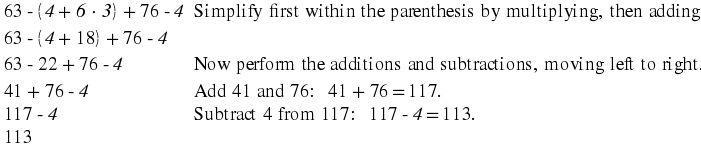

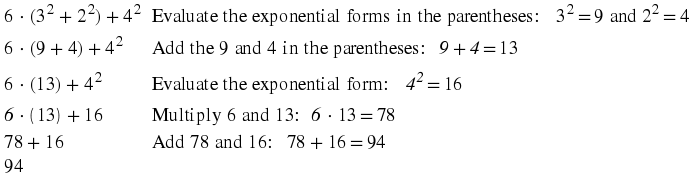

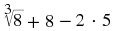

Example 3.15.

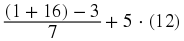

Example 3.16.

Example 3.17.

Example 3.18.

Practice Set C

Determine the value of each of the following.

Calculators

Using a calculator is helpful for simplifying computations that involve large numbers.

Sample Set D

Use a calculator to determine each value.

Example 3.19.

9, 842 + 56 ⋅ 85

| Key | Display Reads | ||

| Perform the multiplication first. | Type | 56 | 56 |

| Press | × | 56 | |

| Type | 85 | 85 | |

| Now perform the addition. | Press | + | 4760 |

| Type | 9842 | 9842 | |

| Press | = | 14602 |

The display now reads 14,602.

Example 3.20.

42 ( 27 + 18 ) + 105 ( 810 ÷ 18 )

| Key | Display Reads | ||

| Operate inside the parentheses | Type | 27 | 27 |

| Press | + | 27 | |

| Type | 18 | 18 | |

| Press | = | 45 | |

| Multiply by 42. | Press | × | 45 |

| Type | 42 | 42 | |

| Press | = | 1890 |

Place this result into memory by pressing the memory key.

| Key | Display Reads | ||

| Now operate in the other parentheses. | Type | 810 | 810 |

| Press | ÷ | 810 | |

| Type | 18 | 18 | |

| Press | = | 45 | |

| Now multiply by 105. | Press | × | 45 |

| Type | 105 | 105 | |

| Press | = | 4725 | |

| We are now ready to add these two quantities together. | Press | + | 4725 |

| Press the memory recall key. | 1890 | ||

| Press | = | 6615 |

Thus, 42(27 + 18) + 105(810÷18) = 6,615

Example 3.21.

16 4 + 37 3

| Nonscientific Calculators | ||

| Key | Display Reads | |

| Type | 16 | 16 |

| Press | × | 16 |

| Type | 16 | 16 |

| Press | × | 256 |

| Type | 16 | 16 |

| Press | × | 4096 |

| Type | 16 | 16 |

| Press | = | 65536 |

| Press the memory key | ||

| Type | 37 | 37 |

| Press | × | 37 |

| Type | 37 | 37 |

| Press | × | 1396 |

| Type | 37 | 37 |

| Press | × | 50653 |

| Press | + | 50653 |

| Press memory recall key | 65536 | |

| Press | = | 116189 |

| Calculators with yx Key | ||

| Key | Display Reads | |

| Type | 16 | 16 |

| Press | y x | 16 |

| Type | 4 | 4 |

| Press | = | 4096 |

| Press | + | 4096 |

| Type | 37 | 37 |

| Press | y x | 37 |

| Type | 3 | 3 |

| Press | = | 116189 |

Thus, 164 + 373 = 116,189

We can certainly see that the more powerful calculator simplifies computations.

Example 3.22.

Nonscientific calculators are unable to handle calculations involving very large numbers.

85612 ⋅ 21065

| Key | Display Reads | |

| Type | 85612 | 85612 |

| Press | × | 85612 |

| Type | 21065 | 21065 |

| Press | = |

This number is too big for the display of some calculators and we'll probably get some kind of error message. On some scientific calculators such large numbers are coped with by placing them in a form called "scientific notation." Others can do the multiplication directly. (1803416780)

Practice Set D

Use a calculator to find each value.

Exercises

For the following problems, find each value. Check each result with a calculator.

Exercise 3.3.25.

18 + 7⋅(4 − 1)

Exercise 3.3.27.

1 − 5⋅(8 − 8)

Exercise 3.3.29.

98÷2÷72

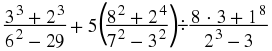

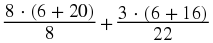

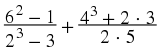

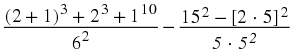

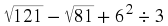

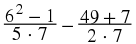

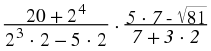

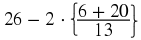

Exercise 3.3.31.

Exercise 3.3.33.

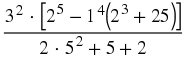

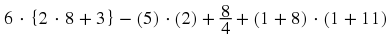

Exercise 3.3.35.

61 − 22 + 4[3⋅(10) + 11]

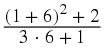

Exercise 3.3.37.

Exercise 3.3.39.

10⋅[8 + 2⋅(6 + 7)]

Exercise 3.3.41.

102⋅3÷52⋅3 − 2⋅3

Exercise 3.3.43.

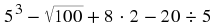

Exercise 3.3.45.

Exercise 3.3.47.

0 + 10(0) + 15⋅{4⋅3 + 1}

Exercise 3.3.49.

(4 + 7)⋅(8 − 3)

Exercise 3.3.51.

(21 − 3)⋅(6 − 1)⋅(7) + 4(6 + 3)

Exercise 3.3.53.

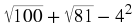

Exercise 3.3.55.

34 + 24⋅(1 + 5)

Exercise 3.3.57.

(7)⋅(16) − 34 + 22⋅(17 + 32)

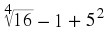

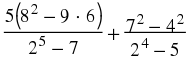

Exercise 3.3.59.

Exercise 3.3.61.

Exercise 3.3.63.

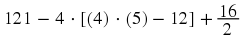

Exercise 3.3.65.

Exercises for Review

Exercise 3.3.67.

(Section 1.7) The fact that 0 + any whole number = that particular whole number is an example of which property of addition?

Solutions to Exercises

Solution to Exercise 3.3.23. (Return to Exercise)

This number is too big for a nonscientific calculator. A scientific calculator will probably give you 2.217747109×1011

3.4. Prime Factorization of Natural Numbers*

Section Overview

Factors

Determining the Factors of a Whole Number

Prime and Composite Numbers

The Fundamental Principle of Arithmetic

The Prime Factorization of a Natural Number

Factors

From observations made in the process of multiplication, we have seen that

( factor ) ⋅ ( factor ) = product

The two numbers being multiplied are the factors and the result of the multiplication is the product. Now, using our knowledge of division, we can see that a first number is a factor of a second number if the first number divides into the second number a whole number of times (without a remainder).

A first number is a factor of a second number if the first number divides into the second number a whole number of times (without a remainder).

We show this in the following examples:

Example 3.23.

3 is a factor of 27, since 27÷3 = 9, or 3⋅9 = 27.

Example 3.24.

7 is a factor of 56, since 56÷7 = 8, or 7⋅8 = 56.

Example 3.25.

4 is not a factor of 10, since 10÷4 = 2R2. (There is a remainder.)

Determining the Factors of a Whole Number

We can use the tests for divisibility from Section 2.5 to determine all the factors of a whole number.

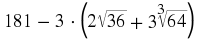

Sample Set A

Example 3.26.

Find all the factors of 24.

The next number to try is 6, but we already have that 6 is a factor. Once we come upon a factor that we already have discovered, we can stop.

All the whole number factors of 24 are 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 8, 12, and 24.

Practice Set A

Find all the factors of each of the following numbers.

Prime and Composite Numbers

Notice that the only factors of 7 are 1 and 7 itself, and that the only factors of 3 are 1 and 3 itself. However, the number 8 has the factors 1, 2, 4, and 8, and the number 10 has the factors 1, 2, 5, and 10. Thus, we can see that a whole number can have only two factors (itself and 1) and another whole number can have several factors.

We can use this observation to make a useful classification for whole numbers: prime numbers and composite numbers.

A whole number (greater than one) whose only factors are itself and 1 is called a prime number.

The first seven prime numbers are 2, 3, 5, 7, 11, 13, and 17. Notice that the whole number 1 is not considered to be a prime number, and the whole number 2 is the first prime and the only even prime number.

A whole number composed of factors other than itself and 1 is called a composite number. Composite numbers are not prime numbers.

Some composite numbers are 4, 6, 8, 9, 10, 12, and 15.

Sample Set B

Determine which whole numbers are prime and which are composite.

Example 3.27.

39. Since 3 divides into 39, the number 39 is composite: 39÷3 = 13

Example 3.28.

47. A few division trials will assure us that 47 is only divisible by 1 and 47. Therefore, 47 is prime.

Practice Set B

Determine which of the following whole numbers are prime and which are composite.

The Fundamental Principle of Arithmetic

Prime numbers are very useful in the study of mathematics. We will see how they are used in subsequent sections. We now state the Fundamental Principle of Arithmetic.

Except for the order of the factors, every natural number other than 1 can be factored in one and only one way as a product of prime numbers.

When a number is factored so that all its factors are prime numbers. the factorization is called the prime factorization of the number.

The technique of prime factorization is illustrated in the following three examples.

10 = 5⋅2. Both 2 and 5 are primes. Therefore, 2⋅5 is the prime factorization of 10.

11. The number 11 is a prime number. Prime factorization applies only to composite numbers. Thus, 11 has no prime factorization.

60 = 2⋅30. The number 30 is not prime: 30 = 2⋅15.

60 = 2 ⋅ 2 ⋅ 15

The number 15 is not prime: 15 = 3⋅5

60 = 2 ⋅ 2 ⋅ 3 ⋅ 5

We'll use exponents.

60 = 2 2 ⋅ 3 ⋅ 5

The numbers 2, 3, and 5 are each prime. Therefore, 22⋅3⋅5 is the prime factorization of 60.

The Prime Factorization of a Natural Number

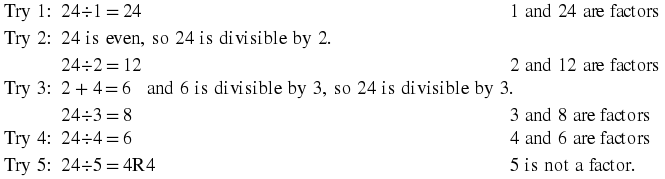

The following method provides a way of finding the prime factorization of a natural number.

The Method of Finding the Prime Factorization of a Natural Number

Divide the number repeatedly by the smallest prime number that will divide into it a whole number of times (without a remainder).

When the prime number used in step 1 no longer divides into the given number without a remainder, repeat the division process with the next largest prime that divides the given number.

Continue this process until the quotient is smaller than the divisor.

The prime factorization of the given number is the product of all these prime divisors. If the number has no prime divisors, it is a prime number.

We may be able to use some of the tests for divisibility we studied in Section 2.5 to help find the primes that divide the given number.

Sample Set C

Example 3.29.

Find the prime factorization of 60.

Since the last digit of 60 is 0, which is even, 60 is divisible by 2. We will repeatedly divide by 2 until we no longer can. We shall divide as follows:

The quotient 1 is finally smaller than the divisor 5, and the prime factorization of 60 is the product of these prime divisors.

60 = 2 ⋅ 2 ⋅ 3 ⋅ 5

We use exponents when possible.

60 = 2 2 ⋅ 3 ⋅ 5

Example 3.30.

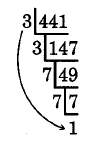

Find the prime factorization of 441.

441 is not divisible by 2 since its last digit is not divisible by 2.

441 is divisible by 3 since 4 + 4 + 1 = 9 and 9 is divisible by 3.

The quotient 1 is finally smaller than the divisor 7, and the prime factorization of 441 is the product of these prime divisors.

441 = 3 ⋅ 3 ⋅ 7 ⋅ 7

Use exponents.

441 = 3 2 ⋅ 7 2

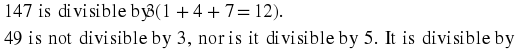

Example 3.31.

Find the prime factorization of 31.

The number 31 is a prime number

Practice Set C

Find the prime factorization of each whole number.

Exercises

For the following problems, determine the missing factor(s).

Exercise 3.4.25.

__________

__________

Exercise 3.4.27.

42 = 21⋅__________

Exercise 3.4.29.

__________

__________

Exercise 3.4.31.

__________

⋅__________

__________

⋅__________

Exercise 3.4.33.

__________

⋅__________

⋅__________

__________

⋅__________

⋅__________

For the following problems, find all the factors of each of the numbers.

Exercise 3.4.35.

22

Exercise 3.4.37.

105

Exercise 3.4.39.

15

Exercise 3.4.41.

80

Exercise 3.4.43.

218

For the following problems, determine which of the whole numbers are prime and which are composite.

Exercise 3.4.45.

25

Exercise 3.4.47.

2

Exercise 3.4.49.

5

Exercise 3.4.51.

9

Exercise 3.4.53.

34

Exercise 3.4.55.

63

Exercise 3.4.57.

924

Exercise 3.4.59.

103

Exercise 3.4.61.

667

Exercise 3.4.63.

119

For the following problems, find the prime factorization of each of the whole numbers.

Exercise 3.4.65.

38

Exercise 3.4.67.

62

Exercise 3.4.69.

176

Exercise 3.4.71.

819

Exercise 3.4.73.

148,225

Exercises For Review

Exercise 3.4.76. (Go to Solution)

(Section 2.3) True or false? Zero divided by any nonzero whole number is zero.

Solutions to Exercises

3.5. The Greatest Common Factor *

Section Overview

The Greatest Common Factor (GCF)

A Method for Determining the Greatest Common Factor

The Greatest Common Factor (GCF)

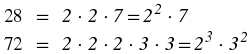

Using the method we studied in Section 3.4, we could obtain the prime factorizations of 30 and 42.

30 = 2 ⋅ 3 ⋅ 5

42 = 2 ⋅ 3 ⋅ 7

We notice that 2 appears as a factor in both numbers, that is, 2 is a common factor of 30 and 42. We also notice that 3 appears as a factor in both numbers. Three is also a common factor of 30 and 42.

When considering two or more numbers, it is often useful to know if there is a largest common factor of the numbers, and if so, what that number is. The largest common factor of two or more whole numbers is called the greatest common factor, and is abbreviated by GCF. The greatest common factor of a collection of whole numbers is useful in working with fractions (which we will do in Section 4.1).

A Method for Determining the Greatest Common Factor

A straightforward method for determining the GCF of two or more whole numbers makes use of both the prime factorization of the numbers and exponents.

To find the greatest common factor (GCF) of two or more whole numbers:

Write the prime factorization of each number, using exponents on repeated factors.

Write each base that is common to each of the numbers.

To each base listed in step 2, attach the smallest exponent that appears on it in either of the prime factorizations.

The GCF is the product of the numbers found in step 3.

Sample Set A

Find the GCF of the following numbers.

Example 3.32.

12 and 18

The common bases are 2 and 3.

The smallest exponents appearing on 2 and 3 in the prime factorizations are, respectively, 1 and 1 ( 21 and 31 ), or 2 and 3.

- The GCF is the product of these numbers.

2 ⋅ 3 = 6

The GCF of 30 and 42 is 6 because 6 is the largest number that divides both 30 and 42 without a remainder.

Example 3.33.

18, 60, and 72

The common bases are 2 and 3.

The smallest exponents appearing on 2 and 3 in the prime factorizations are, respectively, 1 and 1:

21 from 18

31 from 60

The GCF is the product of these numbers.

GCF is 2⋅3 = 6

Thus, 6 is the largest number that divides 18, 60, and 72 without a remainder.

Example 3.34.

700, 1,880, and 6,160

The common bases are 2 and 5

The smallest exponents appearing on 2 and 5 in the prime factorizations are, respectively, 2 and 1.

22 from 700.

51 from either 1,880 or 6,160.

The GCF is the product of these numbers.

GCF is 22⋅5 = 4⋅5 = 20

Thus, 20 is the largest number that divides 700, 1,880, and 6,160 without a remainder.

Practice Set A

Find the GCF of the following numbers.

Exercises

For the following problems, find the greatest common factor (GCF) of the numbers.

Exercise 3.5.7.

5 and 10

Exercise 3.5.9.

9 and 12

Exercise 3.5.11.

35 and 175

Exercise 3.5.13.

45 and 189

Exercise 3.5.15.

264 and 132

Exercise 3.5.17.

65 and 15

Exercise 3.5.19.

245 and 80

Exercise 3.5.21.

60, 140, and 100

Exercise 3.5.23.

24, 30, and 45

Exercise 3.5.25.

210, 630, and 182

Exercise 3.5.27.

1,617, 735, and 429

Exercise 3.5.29.

3,672, 68, and 920

Exercise 3.5.31.

500, 77, and 39

Exercises for Review

Solutions to Exercises

3.6. The Least Common Multiple*

Section Overview

Multiples

Common Multiples

The Least Common Multiple (LCM)

Finding the Least Common Multiple

Multiples

When a whole number is multiplied by other whole numbers, with the exception of zero, the resulting products are called multiples of the given whole number. Note that any whole number is a multiple of itself.

Sample Set A

| Multiples of 2 | Multiples of 3 | Multiples of 8 | Multiples of 10 |

| 2 × 1 = 2 | 3 × 1 = 3 | 8 × 1 = 8 | 10 × 1 = 10 |

| 2 × 2 = 4 | 3 × 2 = 6 | 8 × 2 = 16 | 10 × 2 = 20 |

| 2 × 3 = 6 | 3 × 3 = 9 | 8 × 3 = 24 | 10 × 3 = 30 |

| 2 × 4 = 8 | 3 × 4 = 12 | 8 × 4 = 32 | 10 × 4 = 40 |

| 2 × 5 = 10 | 3 × 5 = 15 | 8 × 5 = 40 | 10 × 5 = 50 |

| ⋮ | ⋮ | ⋮ | ⋮ |

Practice Set A

Find the first five multiples of the following numbers.

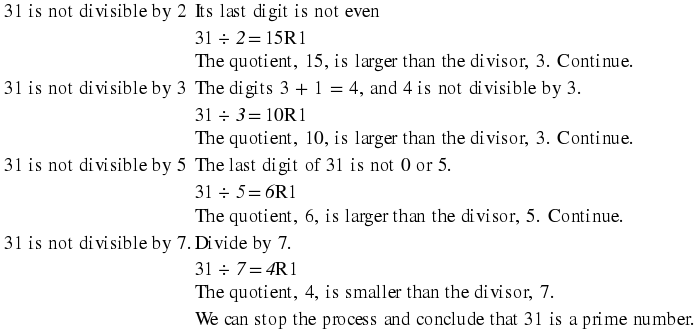

Common Multiples

There will be times when we are given two or more whole numbers and we will need to know if there are any multiples that are common to each of them. If there are, we will need to know what they are. For example, some of the multiples that are common to 2 and 3 are 6, 12, and 18.

Sample Set B

Example 3.35.

We can visualize common multiples using the number line.

Notice that the common multiples can be divided by both whole numbers.

Practice Set B

Find the first five common multiples of the following numbers.

The Least Common Multiple (LCM)

Notice that in our number line visualization of common multiples (above), the first common multiple is also the smallest, or least common multiple, abbreviated by LCM.

The least common multiple, LCM, of two or more whole numbers is the smallest whole number that each of the given numbers will divide into without a remainder.

The least common multiple will be extremely useful in working with fractions (Section 4.1).

Finding the Least Common Multiple

To find the LCM of two or more numbers:

Write the prime factorization of each number, using exponents on repeated factors.

Write each base that appears in each of the prime factorizations.

To each base, attach the largest exponent that appears on it in the prime factorizations.

The LCM is the product of the numbers found in step 3.

There are some major differences between using the processes for obtaining the GCF and the LCM that we must note carefully:

The Difference Between the Processes for Obtaining the GCF and the LCM

Notice the difference between step 2 for the LCM and step 2 for the GCF. For the GCF, we use only the bases that are common in the prime factorizations, whereas for the LCM, we use each base that appears in the prime factorizations.

Notice the difference between step 3 for the LCM and step 3 for the GCF. For the GCF, we attach the smallest exponents to the common bases, whereas for the LCM, we attach the largest exponents to the bases.

Sample Set C

Find the LCM of the following numbers.

Example 3.36.

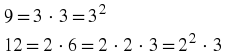

9 and 12

The bases that appear in the prime factorizations are 2 and 3.

- The largest exponents appearing on 2 and 3 in the prime factorizations are, respectively, 2 and 2:

22 from 12.

32 from 9.

- The LCM is the product of these numbers.

LCM = 22⋅32 = 4⋅9 = 36

Thus, 36 is the smallest number that both 9 and 12 divide into without remainders.

Example 3.37.

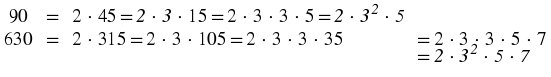

90 and 630

The bases that appear in the prime factorizations are 2, 3, 5, and 7.

The largest exponents that appear on 2, 3, 5, and 7 are, respectively, 1, 2, 1, and 1:

21 from either 90 or 630.

32 from either 90 or 630.

51 from either 90 or 630.

71 from 630.

- The LCM is the product of these numbers.

LCM = 2⋅32⋅5⋅7 = 2⋅9⋅5⋅7 = 630

Thus, 630 is the smallest number that both 90 and 630 divide into with no remainders.

Example 3.38.

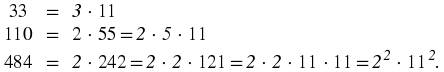

33, 110, and 484

The bases that appear in the prime factorizations are 2, 3, 5, and 11.

The largest exponents that appear on 2, 3, 5, and 11 are, respectively, 2, 1, 1, and 2:

22 from 484.

31 from 33.

51 from 110

112 from 484.

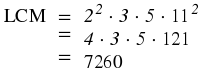

- The LCM is the product of these numbers.

Thus, 7260 is the smallest number that 33, 110, and 484 divide into without remainders.

Practice Set C

Find the LCM of the following numbers.

Exercises

For the following problems, find the least common multiple of the numbers.

Exercise 3.6.17.

6 and 15

Exercise 3.6.19.

10 and 14

Exercise 3.6.21.

6 and 12

Exercise 3.6.23.

6 and 8

Exercise 3.6.25.

7 and 8

Exercise 3.6.27.

2 and 9

Exercise 3.6.29.

28 and 36

Exercise 3.6.31.

28 and 42

Exercise 3.6.33.

162 and 270

Exercise 3.6.35.

25 and 30

Exercise 3.6.37.

16 and 24

Exercise 3.6.39.

24 and 40

Exercise 3.6.41.

50 and 140

Exercise 3.6.43.

8, 10, and 15

Exercise 3.6.45.

4, 5, and 21

Exercise 3.6.47.

15, 25, and 40

Exercise 3.6.49.

84 and 96

Exercise 3.6.51.

12, 16, and 24

Exercise 3.6.53.

6, 9, 12, and 18

Exercise 3.6.55.

18, 80, 108, and 490

Exercise 3.6.57.

38, 92, 115, and 189

Exercise 3.6.59.

12, 12, and 12

Exercises for Review

Solutions to Exercises

3.7. Summary of Key Concepts*

Summary of Key Concepts

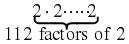

Exponential notation is a description of repeated multiplication.

An exponent records the number of identical factors repeated in a multiplication.

In a number such as 73 ,

7 is called the base.

3 is called the exponent, or power.

73 is read "seven to the third power," or "seven cubed."

A number raised to the second power is often called squared. A number raised to the third power is often called cubed.

In mathematics, the word root is used to indicate that, through repeated multiplication, one number is the source of another number.

(Section 3.2)

(Section 3.2) The symbol

is called a radical sign and indicates the square root of a number. The symbol

is called a radical sign and indicates the square root of a number. The symbol

represents the

n

th root.

represents the

n

th root.

An expression such as

is called a radical and 4 is called the index. The number 16 is called the radicand.

is called a radical and 4 is called the index. The number 16 is called the radicand.

Grouping symbols are used to indicate that a particular collection of numbers and meaningful operations are to be grouped together and considered as one number. The grouping symbols commonly used in mathematics are

Parentheses: ( )

Brackets: [ ]

Braces: { }

Bar: ___

Order of Operations (Section 3.3)

Perform all operations inside grouping symbols, beginning with the innermost set, in the order of 2, 3, and 4 below.

Perform all exponential and root operations, moving left to right.

Perform all multiplications and division, moving left to right.

Perform all additions and subtractions, moving left to right.

A first number is a factor of a second number if the first number divides into the second number a whole number of times.

A whole number greater than one whose only factors are itself and 1 is called a prime number. The whole number 1 is not a prime number. The whole number 2 is the first prime number and the only even prime number.

A whole number greater than one that is composed of factors other than itself and 1 is called a composite number.

Except for the order of factors, every whole number other than 1 can be written in one and only one way as a product of prime numbers.

The prime factorization of 45 is 3⋅3⋅5. The numbers that occur in this factorization of 45 are each prime.

There is a simple method, based on division by prime numbers, that produces the prime factorization of a whole number. For example, we determine the prime factorization of 132 as follows.

![]() The prime factorization of 132 is

2⋅2⋅3⋅11 = 22⋅3⋅11.

The prime factorization of 132 is

2⋅2⋅3⋅11 = 22⋅3⋅11.

A factor that occurs in each number of a group of numbers is called a common factor. 3 is a common factor to the group 18, 6, and 45

The largest common factor of a group of whole numbers is called the greatest common factor. For example, to find the greatest common factor of 12 and 20,

- Write the prime factorization of each number.

- Write each base that is common to each of the numbers:

2 and 3

The smallest exponent appearing on 2 is 2. The smallest exponent appearing on 3 is 1.

- The GCF of 12 and 60 is the product of the numbers

2

2

and

3

.

2 2 ⋅ 3 = 4 ⋅ 3 = 12

Thus, 12 is the largest number that divides both 12 and 60 without a remainder.

There is a simple method, based on prime factorization, that determines the GCF of a group of whole numbers.

When a whole number is multiplied by all other whole numbers, with the exception of zero, the resulting individual products are called multiples of that whole number. Some multiples of 7 are 7, 14, 21, and 28.

Multiples that are common to a group of whole numbers are called common multiples. Some common multiples of 6 and 9 are 18, 36, and 54.

The least common multiple (LCM) of a group of whole numbers is the smallest whole number that each of the given whole numbers divides into without a remainder. The least common multiple of 9 and 6 is 18.

There is a simple method, based on prime factorization, that determines the LCM of a group of whole numbers. For example, the least common multiple of 28 and 72 is found in the following way.

- Write the prime factorization of each number

Write each base that appears in each of the prime factorizations, 2, 3, and 7.

- To each of the bases listed in step 2, attach the largest exponent that appears on it in the prime factorization.

2 3 , 3 2 , and 7

- The LCM is the product of the numbers found in step 3.

2 3 ⋅ 3 2 ⋅ 7 = 8 ⋅ 9 ⋅ 7 = 504

Thus, 504 is the smallest number that both 28 and 72 will divide into without a remainder.

The GCF of two or more whole numbers is the largest number that divides into each of the given whole numbers. The LCM of two or more whole numbers is the smallest whole number that each of the given numbers divides into without a remainder.

3.8. Exercise Supplement *

Exercise Supplement

Exponents and Roots (Section 3.2)

For problems 1 -25, determine the value of each power and root.

Exercise 3.8.2.

43

Exercise 3.8.4.

14

Exercise 3.8.6.

72

Exercise 3.8.8.

112

Exercise 3.8.10.

34

Exercise 3.8.12.

202

Exercise 3.8.14.

Exercise 3.8.16.

Exercise 3.8.18.

Exercise 3.8.20.

Exercise 3.8.22.

Exercise 3.8.24.

Section 3.2

For problems 26-45, use the order of operations to determine each value.

Exercise 3.8.26.

23 − 2⋅4

Exercise 3.8.28.

Exercise 3.8.30.

3⋅(22 + 32)

Exercise 3.8.32.

Exercise 3.8.34.

Exercise 3.8.36.

Exercise 3.8.38.

Exercise 3.8.40.

Exercise 3.8.41. (Go to Solution)

Compare the results of problems 39 and 40. What might we conclude?

Exercise 3.8.42.

Exercise 3.8.44.

Exercise 3.8.46.

An __________ records the number of identical factors that are repeated in a multiplication.

Prime Factorization of Natural Numbers (Section 3.4)

For problems 47- 53, find all the factors of each number.

Exercise 3.8.48.

24

Exercise 3.8.50.

12

Exercise 3.8.52.

25

Exercise 3.8.54.

What number is the smallest prime number?

Grouping Symbol and the Order of Operations (Section 3.3)

For problems 55 -64, write each number as a product of prime factors.

Exercise 3.8.56.

20

Exercise 3.8.58.

284

Exercise 3.8.60.

845

Exercise 3.8.62.

921

Exercise 3.8.64.

37

The Greatest Common Factor (Section 3.5)

For problems 65 - 75, find the greatest common factor of each collection of numbers.

Exercise 3.8.66.

6 and 14

Exercise 3.8.68.

6, 8, and 12

Exercise 3.8.70.

42 and 54

Exercise 3.8.72.

18, 48, and 72

Exercise 3.8.74.

64, 72, and 108

The Least Common Multiple (Section 3.6)

For problems 76-86, find the least common multiple of each collection of numbers.

Exercise 3.8.76.

5 and 15

Exercise 3.8.78.

10 and 15

Exercise 3.8.80.

42 and 54

Exercise 3.8.82.

40, 50, and 180

Exercise 3.8.84.

108, 144, and 324

Exercise 3.8.86.

12, 15, 18, and 20

Exercise 3.8.88.

Find all factors of 24.

Exercise 3.8.90.

Write all divisors of 6⋅82⋅103 .

Exercise 3.8.92.

Does 13 divide 83⋅102⋅114⋅132⋅15?

Solutions to Exercises

Solution to Exercise 3.8.41. (Return to Exercise)

The sum of square roots is not necessarily equal to the square root of the sum.

Solution to Exercise 3.8.89. (Return to Exercise)

1, 2, 4, 5, 7, 8, 10, 14, 20, 25, 35, 40, 50, 56, 70, 100, 140, 175, 200, 280, 700, 1,400

3.9. Proficiency Exam *

Proficiency Exam

Exercise 3.9.1. (Go to Solution)

(Section 3.2) In the number 8 5 , write the names used for the number 8 and the number 5.

Exercise 3.9.2. (Go to Solution)

(Section 3.2) Write using exponents. 12 × 12 × 12 × 12 × 12 × 12 × 12

For problems 4-15, determine the value of each expression.

For problems 16-20, find the prime factorization of each whole number. If the number is prime, write "prime."

For problems 21 and 22, find the greatest common factor.

For problems 28 and 29, find the least common multiple.

Solutions to Exercises

Solution to Exercise 3.9.25. (Return to Exercise)

Yes, because one of the (prime) factors of the number is 7.

Solution to Exercise 3.9.26. (Return to Exercise)

Yes, because it is one of the factors of the number.

Solution to Exercise 3.9.27. (Return to Exercise)

No, because the prime 13 is not a factor any of the listed factors of the number.