4

Global Gentrifiers: Class, Capital, State

Class and the idea of one class (new middle-class gentrifiers) displacing another class (the working class) has long been central to Anglo-American debates and discussions about gentrification (Lees, Slater and Wyly 2008). If gentrification is now global, we must investigate whether it involves a (global) gentrifier class and if it does, how uneven its intervention is going to be across the globe (also see Bridge 2007). Class is one of the most contested concepts in social theory. In this chapter, we do not discuss the middle class per se but rather the ‘new’ middle class as global gentrifiers. Importantly the term ‘new’ middle class in the literature on gentrification from the global North refers to a post-industrial, postmodern, ‘new’ middle class whose values and lifestyles were very different to the traditional middle class (see Ley, 1996, for a detailed account). By way of contrast, the term ‘new’ middle class in the literature on gentrification from the global South refers to a newly emerging or expanding, modernizing middle class with new spending power and associated interest in consumerism. Europe and North America have had welfare systems in place for longer than the ‘Third’ World, as a consequence the middle class is better established there, and has reproduced and mutated (fragmented) over time. By way of contrast, in Asia and parts of Africa the emergence of a middle class is coincident with the post-1970s periods of rapid economic growth with much improved social access to state- and privately provided welfare. In the case of Latin America, as we argue below, the emergence of the middle class is the effect of the rapid economic growth that began in the early twentieth century.

A ‘new’ middle class (like in the Anglo-American literature on gentrification) is rarely compared to a traditional middle class in cities of the global South. Indeed, in many cases a traditional middle class did not exist as such: in other places where one did exist, the old and new middle classes are blurred. The politics and lifestyles of ‘new’ middle-class gentrifiers in the global South are therefore not necessarily in reaction to the politics and lifestyles of a pre-existing (conservative) middle class (see Ley 1996; Butler 1997). What is interesting, however, is that the lifestyles and in many cases the (now rather suburban) values of contemporary gentrifiers in the global North and South are becoming more and more alike. As such, can we identify an emergent global gentrifier ‘new’ middle class? Has gentrification become generalized enough so that gentrifiers have gentrified minds? How important are they as individuals, as human agents, in the process of gentrification around the globe today? And most importantly, has state-led gentrification overtaken the importance of individual gentrifiers?

Some are now arguing that for the first time in history, a truly global new middle class is emerging. Homi Kharas, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institute and a former World Bank economist, and Geoffrey Goertz (2010) project that the new global middle class will rise from 2 billion today to 5 billion by 2030. Until recently the world's middle classes have been located in Europe, North America and Japan, but that is changing rapidly. The European and American middle classes are predicted to shrink from 50 per cent of the total to just 22 per cent. Rapid growth in China, India, Indonesia, Vietnam, Thailand, and Malaysia will cause Asia's share of the new middle class to more than double from its current 30 per cent. By 2030, Asia will host 64 per cent of the global middle class and account for over 40 per cent of global middle-class consumption, mostly fuelled by growth in East Asia. BRIC countries have seen different patterns of economic growth which have brought different social changes. The emergence of a new middle class is more recent in some countries than others. Obviously, estimations of a new middle class are fraught with difficulties, especially when measuring the size of the middle class, let alone defining it, and this is subject to debate (see Chapters 1 and 2 in Chen 2013). Furthermore, such an estimation often reflects state aspirations, making middle-class expansion a political project. For instance, in mainland China, middle-class construction has been a national project that received great emphasis by the Party State (Tomba 2004; see also Zhang 2010). As such, ‘[t]he middle class that the Chinese Party State envisages is clearly the most affluent in China's urbanising society, whose lives are detached from the masses’ (Shin 2014a: 513–14).

In Latin America, especially in Brazil, Chile, Argentina, Uruguay and Mexico, a middle class was formed between the 1930s and 1940s by developmentalist states and massive access to public university education, so there the rise of a middle class is in fact not new. Indeed, in Brazil, by the early 1980s the middle class made up 15 per cent of the population, that figure has now increased to a third. Countries like Argentina and Mexico also grew their middle-class populations in the 1970s and 1980s. In East Asia, the middle classes also grew post-war: in South Korea, the proportion of professional, managerial, and clerical workers (not including sales employees) increased from 6.7 per cent to 16. 6 per cent between 1963 to 1983; in Taiwan, the same workers increased from 11. 0 per cent to 20.1 per cent between 1963 and 1982; and in Hong Kong, white-collar workers increased from 14 per cent in 1961 to 21 per cent in 1981 (Koo 1991). The rise of the middle classes was thus a

significant element in the evolution of the new industrial order in the East Asian countries. Concentrated in large urban centers, they shape the dominant pattern of consumption and urban life styles; they make new political demands; and they spawn new political debates and tactics. The political stance of the middle classes has been a critical element in the recent transitions from authoritarian rule in South Korea and Taiwan.

(Koo 1991: 485)

So a new middle class making new political demands and with somewhat similar values to those that David Ley (1996) talked about as ‘gentrifiers’ in Canada was evident in East Asia at the same time, not later. Growth in China, however, lagged behind but is accelerating. In 2009 only 10 per cent of the population was middle class, in 2014 it was 43 per cent, and by 2030 it is predicted to soar to 76 per cent (see Tomba 2004; Chen 2013; and Shin 2014a on the middle class as a state project to expand the consumption base). Middle-class households are considered to be more urbanized than poorer households, and in mainland China, urbanization, middle class-ization and the proletarianization of rural farmers go hand in hand (Shin 2015).

As we entered the twenty-first century, Rofe (2003) argued for an understanding of gentrification as a strategy of social capital accumulation based upon an appeal to all things global and cosmopolitan, he discussed the emergence of a gentrifying global elite. For Rofe (see also Butler 2007b), gentrifiers reacted to global processes by creating identity in place. These agents of gentrification performed habitus in a time of heightened capitalism and spatial transformation in social, political and economic structures. These place-based performances of identity have been seen as increasingly ‘global’ in character. Indeed, Butler (2010: 4) has argued for a closer and more focused ‘understanding of what it is that particular groups feel has changed for them with the onset of global neo-liberalism, social and economic uncertainty and a general detachment from the norms and values with which they were raised and may now be of little guidance in raising their own children (Sennett 1998)’. His question, however, is a very Euro-American one, harkening back to some sense of social and economic stability that was, and certainly is, not necessarily the case. The ‘new’ middle class in rapidly modernizing countries are more likely looking forwards, not backwards. Many of these are not the gentrifying global or transnational elite that Rofe (2003) discussed. Like the traditional Western middle classes, their class position, however, is unstable and chained to enormous amounts of debt as the cost of living escalates in modernizing societies.

Indeed, Bridge (2007) argues that there is no such thing as a ‘global gentrifier’ and Davidson (2007) argues that gentrification as a global habitat is less about class formation and more a corporate creation. Davidson (2007: 491) argues that global gentrification is ‘less generated by the agency-led creation of habitus (Butler 2003, 2007b; Rofe 2003) . . . and more by the commodified production of habitat. Furthermore, he contends that gentrification globally is ‘less a sociological coping strategy or form of class reproduction’, but rather it is ‘a capital-led colonialization of urban space with relations to globalization in terms of architectural design, investment strategies, social-cache-boosting marketing strategies and “non-local global” lifestyles’ (Davidson 2007: 493). Global commodified forms of gentrification are capital-led developments of urban space that do not need to perform discursive practices (Bridge 2001) nor deploy social capital (Butler 2003). It is corporate property developers who have utilized globalization via architectural aesthetics and place marketing to extend the scale and scope of gentrification.

We agree with Davidson (2007) and argue that planetary gentrification is a capital-led colonization of urban space related to globalization and neoliberalization. From this stance, middle-class gentrifiers can be consumers and sometimes crucially deploy their class power to transform neighbourhoods, but they do not always do so and are not always a necessary condition for gentrification to happen. Then, it is our contention in this book that the role of the middle classes in gentrification needs to be reconsidered. But, gentrification is not simply a corporate creation either; it is more often a creation of the state – local and national. The state often does the preparation work for corporate capital to follow, similar to classical gentrification in the global North where pioneer gentrifiers risked and tamed the frontier for corporate capital to follow. The scale can still be neighbourhood, but equally it can be an entire city. The emerged and emerging new middle classes still have a role to play, but this is more now as consumers rather than producers of gentrification.

Politics

It has long been claimed in the global North that new middle-class gentrifiers were left liberal and held specific, often counter-cultural, beliefs and values that desired political and social reform (Caulfield 1994; Ley 1996; Butler 1997). In the global North, the social contract of the liberal state was with the middle class, not the rich or the poor, but this is breaking down in a privatizing, neoliberalizing world. The Occupy movements that Merrifield (2013b) discusses were/are very much about the breakdown of the social contract with the state. Social, economic and political changes have undermined the connection between the state and the middle classes in the global North, but what about in the global South? We cannot make assumptions that the planet's new middle classes will behave like the previous new middle classes in the global North. The assumption is that as people become more middle class they become more democratic and push a more liberal agenda, but in China it is suggested that the middle class there accept a more autocratic regime in return for the stability of their middle-class lifestyle. By way of contrast, the new middle classes in countries like South Korea have demonstrated liberal values. They ‘have acted as a progressive democratic element in political transitions but the specific meanings and goals of democracy they projected differed significantly from the main concerns of the working class’ (Koo 1991: 486). The temporal emergence of these groups under different economic and political systems is key to understanding: ‘[n]urtured by the state and being the major beneficiaries of the state-led urban accumulation and economic development, China's middle-class populace is unlikely to be an agent of social change; for as long as the state protects their wealth and ensures their current economic position, they would be unlikely to join up with the rest of the society in what Andy Merrifield (2011) refers to as “crowd politics”’ (Shin 2014a: 514). Of course, the rise of any middle class brings about new notions of rights awareness. The new middle class makes new political demands to expand and protect their own rights, but particularly in the context of economic development led by strong, authoritarian states, there is always the trade-off between individual freedom and economic affluence. How the middle classes respond to state elites depends on what kind of pacts are established between the ruling elites and the middle classes (Slater, D. 2010). In Singapore, the People's Action Party has been ruling the country for decades by nurturing the middle class and meeting their material aspirations, effectively creating what Rodan (1992) refers to as ‘dictatorship of the middle class’.

It is worth considering the seemingly similar, and also different, political agendas of new middle-class gentrifiers in the global North and South. One that featured strongly in the gentrification of Vancouver in Canada, and has been seen to be associated with pioneer gentrifiers in other Northern cities, is the ‘livable city’ agenda (see Ley 1987, 1994, 1996; also Lees and Ley 2008 and Ley 2011). Interestingly this same ‘livable city’ agenda (even if it is not called that) is being played out in the global South but differently from the way it did in the global North.

So how do ‘livable city’ agendas in gentrifying cities in the global South compare? Anthropologist Amita Bavisker (2007) discusses the remaking of Delhi through a series of judicial orders: the Supreme Court of India has initiated the closure of all polluting and non-conforming industries in Delhi, displacing an estimated two million people in the process. At the same time, Delhi's High Court ordered the removal and relocation of all squatter settlements on public lands, displacing more than three million people in a city of twelve million people. These actions were set in motion by the filing of public interest litigation by environmentalists and consumer rights groups, who have emerged as an organized force in Delhi, in relation to issues such as urban aesthetics, leisure, safety and health. For the bourgeois environmentalist, the new, modern, Delhi must move production activities outside of the city, like many post-industrial cities did in the global North. City spaces are to be reserved for white-collar production and commerce, and consumption activities. But unlike in Vancouver where the livable city was a quality of life/green environmentalism, in Delhi it is a consumption-oriented environmentalism. Bavisker's (2007) discussion of ‘bourgeois environmentalism’ points to the detrimental impacts of this agenda on the poor, in terms of their displacement. Here, the ‘livable city’ that bourgeois environmentalists in Delhi push for, has been inculcated into a neoliberal programme of gentrification. Clean air and clean spaces are more important than shelter and employment for the poor.

Ghertner (2011), however, disputes the idea that India's new middle class mobilized to reclaim urban space from the poor, gentrifying and ‘cleaning up’ its cities. Using the example of Delhi's Bhagidari scheme, a governance experiment launched in 2000, he argues that urban middle-class power did not emerge from internal changes within the new middle class itself, but was produced by the machinations of the local state. He shows how Bhagidari realigned the channels by which citizens access the state on the basis of property ownership, thus undermining the electoral process dominated by the poor, and in so doing privileging property owners' demands for a ‘world-class’ urban future. He argues that Bhagidari ‘gentrified’ the channels of political participation, respatializing the state by breaking the informal ties binding the unpropertied poor to the local state and thereby removing the obstacles to large-scale slum demolitions. Here, the state itself was heavily implicated in creating and gentrifying political participation, rather than the middle classes themselves being seen as agents of gentrification. Elsewhere Bose (2013, 2014) talks about the neoliberal vision of Marxist leaders in Kolkata/Calcutta as aligned with the bourgeois desires of the middle class (see also Kaviraj 1997).

Lemanski and Lama-Rewal (2013) have critiqued the dominant image of India's middle class as ‘exemplified by glitzy shopping malls and international travel’ as conflating India's new and tiny globalized elite with a large and heterogeneous middle class. Indeed what and who constitutes India's middle class remains uncertain and different for different authors. Authors like Fernandes (2006) who have focused on the ‘new middle classes’ (or what Brosius (2010: 1) calls the ‘arrived middle classes’) ask for dedifferentiation. Importantly, Lemanski and Lama-Rewal (2013: 96) point out that the Indian new middle class are ‘a notion encompassing a normative vision of Indian's future society’ as educated, upwardly mobile with Western consumption habits, if not Westernized values. Fernandes (2006) calls them ‘consumer-citizens’. But Lemanski and Lama-Rewal (2013) argue that this really only represents the upper sections of the middle class. There remains a lot of ambiguity which demands further deconstruction of the Indian middle classes and their political agency.

Koo (1991) discusses both the similarities and differences between South Korea's new middle classes and those in the West. He points to the fact that there are also two diverging views of the politics of the new middle class in South Korea – some argue they have been politically very progressive and acted as an important democratic force, while others argue that they were basically conservative and maintained authoritarian regimes. In terms of the former, he talks about the fact that the South Korean new middle classes played a much more significant role than their counterparts in the West did in working-class struggles. The reason, he argues, is historical, for the Korean new middle class emerged

as a significant social stratum before the bourgeoisie established its ideological hegemony and before industrial workers developed into an organized class…Occupying a relatively more autonomous position from state control than wage workers do, intellectuals, students, and other white-collar workers participated actively in political struggles against the authoritarian regimes, exerting strong influence on the consciousness and organization of industrial workers.

(pp. 486–7)

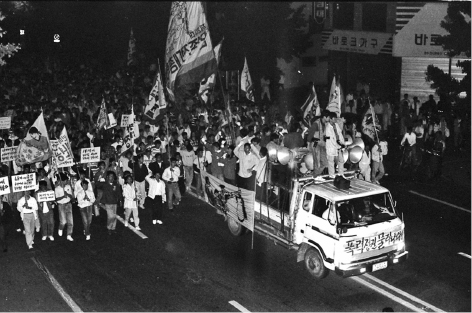

Koo (1991) is a wonderful early comparative urbanism of the new middle class in South Korea and the West. The rise of the developmental state, borrowing technology from abroad meant that class positions and relations were somewhat different. He makes some important comparisons: timing – in the West the new middle class emerged after the bourgeoisie had established its hegemony and the formation of a large and very political working class, largely due to the benefits of the welfare state. In the newly industrialized countries of East Asia, the new middle class emerged at the same time as, and in some cases before, the rise of the capitalist and the working classes. Due to their high status, a relic of the Confucian tradition, Korean intellectuals (with social status and moral superiority above other groups) filled a gap in terms of ideological formulation and social movements. It was Korean intellectuals who became increasingly politicized and criticized the authoritarian political structure (see Figure 4.1). The counter-cultural political activities of South Korea's new middle class certainly echoed those in North America:

In April 1960, the middle classes, both white-collar workers and small business owners, provided strong support to students, who eventually succeeded in toppling the dictatorial government of Syngman Rhee. In the 1971 presidential election, a large majority of the urban middle-classes cast votes for the opposition candidate, Kim Dae-Jung as a protest against Park Chung Hee's attempt to remain in power indefinitely. The middle classes revolted again in 1985. . . In this election, the New Democratic Party, which had been formed for no more than three months by old opposition politicians whose civil rights had just been restored after several years' incapacitations, swept across urban middle-class districts, although it also drew a strong support from the working class. The most dramatic incident of the middle-class involvement in the Korean democratic struggles occurred in June 1987, when a large number of white-collar workers joined the students' street protests against Chun's refusal to amend the constitution for a direct presidential election.

(Koo 1991: 490–1)

Protests on the streets were a large part of the counter-cultural politics of the 1960s that David Ley (1996) and others discussed as conditions of gentrification in the West. Koo (1991) argues that the diverging theses on the new middle class in South Korea, as to whether supporting democracy or the status quo/authoritarian regimes, mirrors debates about the political character of the new middle class in Europe and North America, that middle-class politics are not stable, nor consistent, that they have contradictory material interests, and so on. Marxists would argue that this is because the middle class is a class in-between the bourgeoisie and proletariat, their politics oscillating between the ideologies of the two. As Poulantzas has argued (1975: 289) ‘the petty-bourgeois ideological sub-ensemble is a terrain of struggle and a particular battlefield between bourgeois and working-class ideology’. Koo (1991) explains the difference in terms of the fact that the middle class is not a homogenous social group. Lett (1998) argues that above all South Korea's urban middle classes (pre Asian crisis) sought improved social and economic status, a relic of traditional ways, making them quite different to the classic left liberal gentrifiers in London and New York City. In some ways, if one reviews Koo's timeline, it looks like South Korea's new middle-class transition from progressive to more conservative, in some ways mirrors David Ley's (1996) thesis on hippie to yuppie in Canada. This symbolizes the ‘gentrification of the mind’ (Schulman 2012), as a rebellious culture gets replaced with a conservative culture linked to mainstream consumerism. During the post-2008 financial crisis, the South Korean middle classes felt threatened in terms of maintaining their material wealth, and the middle class itself began to disintegrate, mostly downgrading due to the loss of their wealth (due to labour market restructuring and economic difficulties). As a result they have become increasingly conservative, supporting a conservative government that rhetorically keeps promising that the state will boost the property market – hence their political characteristics are quite different from what they used to be in the 1970s and 1980s. A good comparison would be Greece after its economic collapse and enforced austerity measures, where the middle class is also dissipating rapidly due to economic restructuring.

Our hypothesis is that middle-class politics in the case of East Asia, for instance, can be entwined with material aspiration and the speculative urbanization that builds on an increase in property wealth (also see Ley and Teo 2014, on the ‘culture of property’ in Hong Kong and Hsu and Hsu 2013 on the ‘political culture of property’ in Taiwan). We suggest that there is a close nexus between (a) political orientation in the context of condensed urbanization and industrialization (where ruling hegemony is in the making at the same time as middle-class construction); and (b) the material gains from gentrification, which lead to the affluence of the middle class, who invest in property assets as speculative urbanization takes place (see Shin and Kim 2015).

Lifestyle and consumption

Consumption-side explanations found in gentrification theory from the global North have stressed the role of choice, consumption, culture and consumer demand (see Chapter 3 in Lees, Slater and Wyly 2008 for detail). The key player in these explanations was/still is the ‘new’ middle-class ‘gentrifier’ and their consumption behaviours which are seen to trigger the gentrification process. David Ley (1996) argued that this ‘new cultural class’ was a product of the emergence of a new post-industrial society, and that they were liberals who sought to escape the banal routines, conservatism, and oppressive homogeneity of suburban life, seeking residence in the diverse inner city. Gentrification was the opposite of suburbanization. Lees (2000) termed this an ‘emancipatory city thesis’; it has links to earlier notions of the European industrialized city as an emancipatory site where incomers could cast off the shackles of rural life (Lees 2004). Except for Caulfield (1994) and Ley (1996) gentrifiers cast off the shackles of suburban life. By way of contrast cities outside of the West, like those in Africa or Asia, were seen to be stuck in the past, in un-modernity, and as such, were not seen as emancipatory. Developmentalism played on their un-modernity.

When considering gentrification in the global South, this particular Western consumption thesis makes little sense (see Lees 2014a). For example, the large-scale suburbanization associated with the industrial/modern city in early to mid twentieth-century Euro-America did not happen in Chinese or Latin American cities. So, the idea of gentrification as a counter-cultural idea posited against the modern suburbs has no traction. Rather, the old German saying ‘city air makes men free’ (Stadtluft macht frei), free from the shackles of the rural, liberation from feudal master-servant relations, may have more purchase; or comparisons with the suburbs being built at the same time as inner cities being gentrified in cities in the global South, as in the case of mainland China, e.g. Beijing (see Fang and Zhang 2003) . With no experience of the post-war hegemony of suburban life, gentrifiers outside of Western cities will undoubtedly have different mindsets. In Latin America, urban development was disassociated from industrial growth and cities grew not through the densification of their city centres but through extension into peripheral areas. As such, the return of the middle class to Latin American inner cities and the subsequent displacement of the working class has been less common than in the US or Europe (Inzulza-Contardo 2012). In some countries, the new gender order of post-Fordism that pushed women into the workplace and created dual career households (see Rose 1984; Bondi 1991; Warde 1991) did not happen in tandem with the emergence of gentrification. For example, in China, gender relations have been fairly static since 1949 when there was a huge mobilization of women into paid work. The drive of socialism from the 1950s set up communal eating places, laundries and creches, meaning that women could work and manage family life more easily (Rai, 1995). By way of contrast, as the economy marketized, it became more difficult for women who could be pushed out of jobs in favour of men and profitability, and women's rights have long been subdued in the interests of class politics (see also Yang 2010).

Ren (2013) describes the new urban middle class in China, for example Ms. Zhang, who was ‘young, educated, English speaking, career-orientated, technology savvy (and lived) a lifestyle not that dissimilar to (her) counterparts in other global cities…’ (p. 172–3). Ren (2013) does not discuss the new urban middle class's ideological disposition to the gentrified inner city as anti-suburban; rather, it seems the suburbs just do not figure in the mindsets of these gentrifiers. Their lifestyle demands are much more orientated towards conspicuous consumption. As Wang and Lau (2009) point out, the professional middle classes in China are attracted by the image of elite life and thus willing to pay for the symbolic value of those elite enclaves which they can afford. They also possess cultural competence to decode and appreciate an urbane lifestyle.

Inzulza-Contardo (2012) concludes from his research in the historic Bellavista neighbourhood of Santiago de Chile that gentrifiers there are different to those in the global North – they are tenants rather than owners and they do not align with the white collar profile of ‘Northern gentrifiers’ in a high-income bracket. Rather they are light blue collar workers living in flats. The Chilean housing market advertises these flats as lofts, studio units and with luxury facilities like in the North. These gentrifiers are in tertiary sector jobs with new middle-low incomes. Their consumption is encouraged by globalized commodities. This is quite different to the more individualized, conspicuous thrift of classical gentrifiers in the global North (see Ley 2003). Anyway, in Chile, these pockets of historic gentrification are insignificant in comparison to the large-scale redevelopment of central areas of Santiago (see López-Morales 2010).

As we say in Chapter 2, the scale of gentrification in the South needs to be carefully taken into account as it does not replicate the classical micro-neighbourhood narratives of the North. For instance, Contreras (2011) claims that in Chile, the middle classes that ‘consume’ residential gentrification in the inner areas of the city respond to a wholly significant demographic and cultural change in Chilean society, with current household structures increasingly differentiated and responding to complex residential choices. Hence, Santiago's inner area now attracts younger households often with one or two children, young professionals who recently left their parents' nest (often first university generations), single or separated women with or without children, sexual minorities, and even relatively wealthy Latin American immigrants, among other groups. Their residential choices are based on the advantages of spatial proximity to jobs, services and public goods that exist in the central areas, and also more proximity to their social networks and family (also see spatial capital, Rerat and Lees 2011). Contreras (2011) argues that in Santiago there has been a succession of middle/professional classes, as residential gentrification is mixed with the studentification (Smith 2005) of certain areas that has been pushed by educational/real estate economic conglomerates.

Gay and lesbian gentrifications have been part and parcel of discussions of gentrification in Anglo-American cities, and indeed of gentrification as a counter-cultural, emancipatory practice (see Lees, Slater and Wyly 2008: 209–13). There has been much less discussion elsewhere on the globe, but it is apparent that gentrification and gay rights do have some purchase in some cities. Buenos Aires is one example where, as part and parcel of its touristification (see Herzer et al. 2015), gay guest houses (e.g. Lugar Gay in San Telmo) have opened where only gay men can book a stay. There is some interesting future work to be done on sexual politics and gentrification, especially in Latin America where same-sex civil unions have been legalized in Argentina and in some states in Mexico and Brazil. In Colombia same-sex couples now have inheritance rights and can add their partners to health insurance plans. Coming out of very Catholic countries, this is striking. Ironically these Latin American countries now seem ahead of the progressive curve in comparison to some Western European countries. Contemporary Argentina is very interesting in terms of some of the parallels (and differences) between the sexual revolution and counter cultural politics in the global North, as Argentinian youth now practice sexual and other freedoms. The sexual politics of gentrification in the global South is food for thought. In East Asia, any relationship between gentrification and sexuality is mitigated by the state. Although gay sex is illegal in Singapore, it has been legal in China since 1997. As such in Beijing, for example, it may be that gay Chinese couples do not feel the need to congregate in a neighbourhood like the Castro in San Francisco. Finally, the bulk of the Anglo-American literature on gay gentrification, to date, has viewed it in an emancipatory light, but might it be time now to turn this on its head and consider whether gay gentrification leads to homophobia? In the same way that the social mixing caused by gentrification and mixed communities policy causes social tectonics, conflict and segregation might it be that gentrified gay enclaves increase external hostility?

Fernandes (2009: 220) offers some food for thought when thinking about the consumption thesis and gentrification in the global South:

Existing studies of middle class consumption in India have tended to reinforce a consumer preference model of analysis – one that has addressed the relationship between economic change and consumer aspirations and behaviour. While such research has yielded valuable insight into questions of subjectivity and cultural change, there is a greater need for an understanding of the systemic relationship between consumption and the restructuring of state developmental regimes under liberalization.

In gentrification around the world today, the state plays a key role. When the (now) classic consumption theses emerged in gentrification studies in the global North (see Lees, Slater and Wyly 2010: 127–88), they were concerned less with the state and more with the impact of the transition to a post-industrial society and postmodern culture on the individualized consumption of a new class. The relative omission of the state and the focus on individualization does not aid conceptualization of the relationship between lifestyle and consumption and the state today – the role of the state is much more significant; post industrialism has progressed globally and what was individualized consumption (class gentrification) is now a global product (and indeed any individuality has now been mass produced). Gentrification researchers need to refine or look for a different conceptual model when looking at consumption and lifestyle with respect to gentrification in the global South.

Historic preservation: gentrifier or state-led?

From Xintiandi in Shanghai, Asakusa in Tokyo, to Bercy in Paris, numerous historic districts are undergoing a process of Disneyfication, in which they are remolded into theme parks in the service of the global consumerist elite.

The relationship between gentrification and historic or urban preservation is no longer the now classic Jane Jacobs' (1961) social movement type story. Rather, it is now state-led. The classic story of historic preservation is of Jane Jacobs' fight to ‘save’ Greenwich Village in New York City from the federal bulldozers of Robert Moses' urban renewal. Jacobs' thesis on old neighbourhoods underlined a social movement of historic preservationism in cities across the US. She asserted: ‘New ideas must use old buildings.’ Osman (2011: 83) has described the desires of Brooklyn's ‘brownstoners’ (pioneer or first wave gentrifiers) as ‘a new romantic urban ideal’.

The relationship between historic preservation and gentrification, however, was not just apparent in New York City (or the global North) but also in the global South. The earliest waves of gentrification in Istanbul in the 1980s, for example, demonstrated very similar processes. The early actors in the preservation and gentrification of the late nineteenth and early twentieth century two and three storey row houses in the inner city neighbourhoods of Kuzguncuk, Arnavutkoy and Ortakoy near the Bosphorus, were individuals and small investors. In the 1990s gentrification in Istanbul spread into Beyoglu, the historic centre of the city which held late nineteenth and early twentieth century row apartment buildings. Many of these neighbourhoods are now historic preservation districts. But like in the global North, the early actors (pioneer gentrifiers) were to be replaced by the state after 2005.

In Latin America, historic preservation and gentrification is also related. In fact, international forces enticed Latin American governments to engage in heritage tourism to repopulate and redevelop central cities as early as the 1970s. In 1977, the Organization of American States sponsored a conference that issued the Quito Letter, an agenda to transform historic centres into heritage tourism. Urban competiveness promoted by the Inter-American Development Bank urged local governments to undertake urban renewal. There were projects in Sao Paulo, Buenos Aires, Mexico City, Puebla, Santiago de Chile, Lima, Bogota, and more (see for example, Nobre 2003; Herzer 2008; López-Morales 2010). The International Development Bank, the Inter-American Development Bank, and the World Bank all targeted UNESCO-designated sites offering packages to local (and national) regimes for historic preservation. The regimes looked to the past, ‘depicting the elites formerly inhabiting central areas as paradigms of civility’, as such renovation was a ‘class reinstatement through the “rescue” of…elite values and virtues’ (Betancur 2014). In Sao Paulo, Mexico City and Buenos Aires, in particular, extreme efforts at class replacement were made by condemning and acquiring buildings, plazas and monuments and renovating them for museums, cultural institutions and tourism. Governments agreed to coordinate the displacement of lower class residents as part of the requirements for the above banks lending them money. It was thought that this cleansing would attract the private sector into these city centres, but it has failed for the most part as it is not self-sustaining.

Significantly, where the Quito Letter was signed and where heritage conservation policies have been paramount, is the place where class-motivated revanchism has been better articulated outside the global North (see Swanson 2007, 2010). Inspired by zero-tolerance policies (see Chapter 5), Ecuadorean state-entrepreneurial urban regeneration projects have aimed to cleanse the streets of Quito (and also Guayaquil, the second largest city in Ecuador) of informal workers, beggars, and street children. Swanson shows that race and ethnicity are two devices through which the dominant middle-class oriented, globalized aesthetic for historical centres in the Andes unfolds, also showing how a project of ‘blanqueamiento’ or ‘whitening’ takes place, displacing already marginalized individuals from public spaces like streets and parks, and pushing them into more difficult circumstances outside of where informal jobs on inner city streets and mixed sources of small income exist.

Based on an analysis of Panama City's Belle Époque style Casco Antiguo, Sigler and Wachsmuth (2015) claim that there are novel pathways for gentrification there, much more connected not just with the in and out flows of financial capital but also the increasing real estate and cultural interest by a transnational middle class. As Panama shows, redevelopment capital is often connected to local housing demand not within a single city-region but along transnational pathways, thus creating housing reinvestment profit and also threats of displacement for the original population too. This ‘globalized’ market condition started to exist after a series of preservationist legislations were passed in the 1970s, and largely intensified with the 1997 UNESCO heritage designation that limited the potential for large-scale redevelopment, crucially catalyzing both international and domestic interest in the neighbourhood. Currently, in Casco Antiguo, rents in refurbished units range from approximately US$1,000 to US$4,000 per month, in a city where 57 per cent of residents pay less than US$200 per month in mortgages or rent. In addition, renovated apartments within the area are sold for between approximately $150,000 and $2 million. This is clearly beyond the capacity of most local inhabitants, even large numbers of the wealthy middle classes that anyway prefer newer suburban areas with a different set of amenities and cultural associations. The process of residential conversion and the developments in Panama Casco Antiguo are aimed at, and cater for, international tourists and expatriate residents. The neighbourhood's demographic composition has changed radically.

In some parts of the global South, gentrification has seemingly progressed the opposite way round from gentrification in the global North – progressing from large scale and new to small scale and old. As Lees (2014a) discusses – in China, for example, the ‘new’ middle classes are looking back to traditional architecture – expressing a yearning for traditional Chinese culture as a means through which to express their ‘cultural taste’. Gentrification processes in China began as large-scale urban renewal, imitating Western modern, new-build, high-rise architecture, but have moved on somewhat and now show an interest in social responsibility through environmentally sustainable design and technologies, and in traditional architecture as seen in the preservation of ‘hutongs’ and ‘lilongs’ in inner city Beijing and Shanghai respectively. A hutong is a narrow street that has small single-storey houses coming off it, and the houses are normally made up of four buildings facing into a central courtyard. A lilong is a traditional urban alley community; the community is tightly interlinked – not just physically but also socially – because the residents also run the local shops and restaurants in the street. In the first wave of gentrification, many hutongs were knocked down to make way for new, dense, Western style housing developments; now they are more likely to be gentrified by rehabilitation/preservation rather than demolition and reused as new trendy cafes and shops, their market – the well-off young Chinese who want to feel cool (see Shin 2010, on Nanluoguxiang in Beijing). Often, historic neighbourhoods are preserved not through in situ upgrading but through wholesale clearance and reconstruction to mimic old styles, a process that locals sometimes refer to as ‘fake-over’, as happened in Qianmen, Beijing's centuries-old market place south of the Forbidden City.

Significantly, historic preservation has not been initiated by pioneer gentrifiers like it was in the global North (see Lees, Slater and Wyly 2008). Rather it is state-or developer-led. It is mainly historical buildings from the city's colonial pasts that are recycled in global city building processes. Ren (2008) discusses that from the end of the 1990s, Shanghai's city government began to support historic preservation by passing a series of preservation laws and turning large numbers of historic buildings into landmarks:

the buildings listed for preservation were predominantly Western-style architecture from the colonial period before 1949. Buildings from the following socialist era are mostly regarded as worthless for preservation and eligible for demolition as they age. Only recently, responding to the criticisms about the lack of preservation for architecture from the socialist era, a few buildings built after 1949 were added to the preservation list.

(p. 30)

The distinct temporal waves of Northern gentrification are all happening at once in China, and in a back to front way (not historic preservation to state-led new build, but state-led new build to historic preservation), underlain by the growth of a new middle class and a new consumerism. Ren (2008) makes clear that historic preservation in Shanghai is very pragmatic; it is about potential economic return not only in terms of the local economic base and attracting investment and tourists but also from property appreciation. As she says: ‘old historical buildings in Shanghai, once regarded as worthless in the frenzied development boom of the 1990s, have been rediscovered for their economic value’ (p. 31). She talks about the Mayor of Shanghai's new slogan in 2004, which reads: ‘Building new is development, preserving old is also development’. Historic preservation is therefore another and a more sophisticated tool than demolition employed by the government to achieve urban economic growth. It is not about cultural heritage so much as economic return.

Ren discusses the preservation of Xintiandi, two blocks of old Shikumen houses from the 1930s, which is regarded as the turning point from demolition (Chai) to preservation (Bao) in Shanghai. Unlike in early examples of historic preservation/conservation in London and New York City which saw pioneer gentrifiers investing sweat equity, international architectural firms played key roles, including one involved in the redevelopment of Faneuil Hall in Boston. Also, unlike in the examples in the gentrification literature from the global North, the preservation was not undertaken so people could live in the buildings: rather, they were redeveloped as shops, restaurants and night clubs. The only residential traces were in one of the houses which was converted into a museum, featuring an exhibition of everyday residential life in a Shikumen house in colonial Shanghai. Unlike in New York City, for example, where historic preservation was a bottom up social movement, in Shanghai, it is a top down instrument that sells a globalized image of modern Shanghai in the 1930s as one where wealthy middle-class families sent their children to English speaking schools, watched Hollywood movies and listened to Jazz (see Ren 2008: 36). The idea is to show that Shanghai was an international metropolis in the past and to feed this through to its global city future. The image is a cosmopolitan one, a hybrid of old and new. Historic preservation in Chinese gentrification is about creating a modern space, quite different then to that in the global North. Those displaced by the process, however, tell familiar stories to those displaced by gentrification in Western cities: ‘Resident A (a man in his 50s) My family has lived here for three generations. Before the Liberation (1949), my grandfather bought the house. I have the contract. I don't want to live in the suburbs. There are no hospitals. It takes hours to get to the city and see a doctor by bus’ (cited in Ren, 2008: 39).

Zhang (2013) provides insight into the comparative politics and urbanisms of historic preservation in Beijing, Chicago and Paris, demonstrating well the importance of specific structures of urban governance and the very different histories of urban transformations in cities. In Chicago, historic preservation was/is about improving the local tax base, in Paris it was/is about protecting French cultural integrity and national pride, whereas in Beijing it was/is a tool for local government to promote economic growth. In Beijing, from the early 1990s, when Beijing's Municipal government launched its citywide housing renewal project, many old neighbourhoods and buildings were demolished – in the face of widespread criticism, the government introduced preservation laws, designated preservation districts and added to funds to renovate historic structures. But the pace of demolition did not slow down, and Zhang (2013) argues that the result was a merely ‘symbolic’ urban preservation that ‘serves primarily as a tool to smooth the functioning of the growth machine and to create a better global image for the city’ (p. 24) (for comparison see He 2012; and Shin 2014b on Guangzhou; see Figure 4.3).

Elsewhere in East Asia, in Hong Kong, Singapore and South Korea heritage conservation or attention to historic neighbourhoods is gaining real weight for a diverse set of reasons: (a) heritage buildings are gaining higher exchange value; (b) waves of new-build gentrification are rendering historic dwellings and neighbourhoods more scarce (scarcity); (c) authenticity (albeit manufactured to a large extent) is claiming monopoly rents; (d) nationalism, as in China, has become a state-promoted ideology, emphasizing heritage preservation (selectively) (see Broudehoux 2004); and (e) Singapore sees selective conservation as a tool for ethnic policy (see Kong and Yeoh 1994; Yeoh and Huang 1996; Chang and Teo 2009; Chang and Huang 2005). And in Hong Kong, heritage conservation has been staged as a fight against state-led urban development, for example, the Star Ferry pier struggles (see Hayllar 2010).

Conclusions

Sassen (2006) identifies a new global class whose spaces are in cities in both the global North and South – but only in parts of these cities. She argues that a new global class in Sao Paulo, Johannesburg and New York interfaces more with elites in other world cities than with the populations in their own cities and countries. Her new global class has more in common with the highly mobile, transnational class (see Butler and Lees 2006, for a critique). Gentrifiers around the globe include these folk as we see in Panama and other cases, but gentrifiers (the new middle classes) globally are a much more diverse entity in terms of income (some are very rich, some lower-middle class), politics (some are liberal, some are conservative even authoritarian), and lifestyles (some are highly consumer-orientated, others much less so). There is a truly elite gentrifying class in, for example, African cities, and a less wealthy body of gentrifiers in, for example, some Latin American cities, like Buenos Aires. This presents a rather muddled picture globally. But what is clear is that gentrifiers in the global South are not the same as the classic ‘new’ middle-class gentrifiers in Anglo-America. In the Communist Manifesto, Marx and Engels (1848/1967) wrote that the rise of the bourgeoisie ‘compels all nations, on pain of extinction, to adopt the bourgeois mode of production; it compels them to introduce what it calls civilization into their midst, i.e., to become bourgeois themselves. In one word, it creates a world after its own image’ (p. 84). Global gentrifiers are now both bourgeois and the aspiring bourgeois, and globally this is what they have most in common. There are other convergences too, for gentrification around the planet seems to have adopted a suburban mindset, a conservative ‘gentrified mind’. Very often national and local-level policies of urban change meet their goal and aim to satisfy their urban preferences as consumers, but this does not mean always and everywhere the middle class decisively exert class power to transform the neighbourhood (Davidson 2007). It is the nexus between planetary gentrification and planetary suburbanization and urban and suburban mindsets that needs further research globally.

The fact is, however, that the global gentrifier as a (human, individual) agent of gentrification is insignificant now not just in the global North but in the global South too. The key actor in planetary gentrification is the state – neoliberal or authoritarian. The growth of a new middle class globally in terms of the rising demand for new housing coupled with growing interests in real estate investment in producing new ‘gentrified’ urban forms is important, but it is the state that is the key constituent in gentrification in the global South and East. Seen from the South, the rise of the new middle class and its higher consumption power may not be a precondition for gentrification to occur, but a necessary condition alongside other structural causes, or even, gentrification can be an effect of broad policies oriented to reconfigure the spaces of social reproduction of cities and countries.

In addition, there are new ‘gentrifications’ by the super-rich, not the super-gentrifications that Lees (2003) and Butler and Lees (2006) have discussed that are connected to the global finance industries, but hyper-gentrifications caused by super-rich elites from the global North and the global South investing across borders, e.g. mainland Chinese investing in London and Hong Kong (Hong Kong's property boom post-2008 was helped by an influx of mainland Chinese hedging their risks and diverting their assets away from mainland China), or middle-Eastern oil wealth or Russian elites/oligarchs investing in overseas property markets (London's inflated property market has been blamed on these overseas investors). In London, in neighbourhoods as diverse as Kensington and Chelsea, Notting Hill, Hampstead and St. John's Wood, the wealthy middle classes are being displaced by a new super rich. Moreover, developers are undertaking new-build gentrifications across large swathes of London in anticipation of this money. These transnational investors are important. Indeed, it is our contention that planetary gentrification is produced less by global gentrifiers (the global North and South's new middle classes) and more by (trans)national developers, financial capital and transnational institutions including international financial organizations like the IMF and the World Bank, all of which the state courts.