From The Naval History of the War of 1812

This lake, which had hitherto played but an inconspicuous part, was now to become the scene of the greatest naval battle of the war. A British army of 11,000 men under Sir George Prèvost undertook the invasion of New York by advancing up the western bank of Lake Champlain. This advance was impracticable unless there was a sufficiently strong British naval force to drive back the American squadron at the same time. Accordingly, the British began to construct a frigate, the Confiance, to be added to their already existing force, which consisted of a brig, two sloops, and 12 or 14 gun-boats. The Americans already possessed a heavy corvette, a schooner, a small sloop, and 10 gun-boats or row-galleys; they now began to build a large brig, the Eagle, which was launched about the 16th of August. Nine days later, on the 25th, the Confiance was launched. The two squadrons were equally deficient in stores, etc.; the Confiance having locks to her guns, some of which could not be used, while the American schooner Ticonderoga had to fire her guns by means of pistols flashed at the touchholes (like Barclay on Lake Erie). Macdonough and Downie were hurried into action before they had time to prepare themselves thoroughly; but it was a disadvantage common to both, and arose from the nature of the case, which called for immediate action. The British army advanced slowly toward Plattsburg, which was held by General Macomb with less than 2,000 effective American troops. Captain Thomas Macdonough, the American commodore, took the lake a day or two before his antagonist, and came to anchor in Plattsburg harbor. The British fleet, under Captain George Downie, moved from Isle-aux-Noix on Sept. 8th, and on the morning of the 11th sailed into Plattsburg harbor.

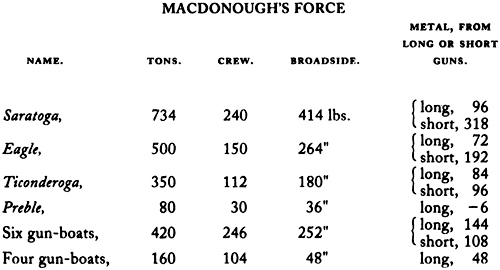

The American force consisted of the ship Saratoga, Captain T. Macdonough, of about 734 tons,1 carrying eight long 24-pounders, six 42-pound and twelve 32-pound carronades; the brig Eagle, Captain Robert Henly, of about 500 tons, carrying eight long 18’s and twelve 32-pound carronades; schooner Ticonderoga, Lieut.-Com. Stephen Cassin, of about 350 tons carrying eight long 12-pounders, four long 18-pounders, and five 32-pound carronades; sloop Preble, Lieutenant Charles Budd, of about 80 tons, mounting seven long 9’s; the row-galleys Borer, Centipede, Nettle, Allen, Viper, and Burrows, each of about 70 tons, and mounting one long 24- and one short 18-pounder; and the row-galleys Wilmer, Ludlow, Aylwin, and Ballard, each of about 40 tons, and mounting one long 12. James puts down the number of men on board the squadron as 950,—merely a guess, as he gives no authority. Cooper says “about 850 men, including officers, and a small detachment of soldiers to act as marines.” Lossing (p. 866, note 1) says 882 in all. Vol. xiv of the “American State Papers” contains on p. 572 the prize-money list presented by the purser, George Beale, Jr. This numbers the men (the dead being represented by their heirs or executors) up to 915, including soldiers and seamen, but many of the numbers are omitted, probably owing to the fact that their owners, though belonging on board, happened to be absent on shore, or in the hospital; so that the actual number of names tallies very closely with that given by Lossing; and accordingly I shall take that.2 The total number of men in the galleys (including a number of soldiers, as there were not enough sailors) was 350. The exact proportions in which this force was distributed among the gun-boats can not be told, but it may be roughly said to be 41 in each large galley and 26 in each small one. The complement of the Saratoga was 210, of the Eagle, 130, of the Ticonderoga, 100, and of the Preble, 30; but the first three had also a few soldiers distributed between them. The following list is probably pretty accurate as to the aggregate; but there may have been a score or two fewer men on the gun-boats, or more on the larger vessels.

In all, 14 vessels of 2,244 tons and 882 men, with 86 guns throwing at a broadside 1,194 lbs. of shot, 480 from long, and 714 from short guns.

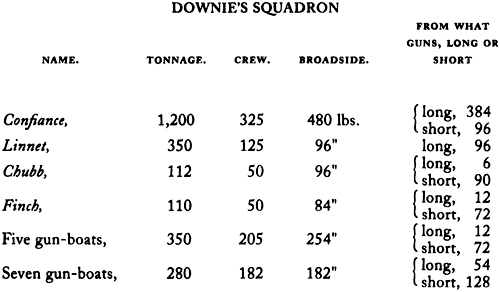

The force of the British squadron in guns and ships is known accurately, as most of it was captured. The Confiance rated for years in our lists as a frigate of the class of the Constellation, Congress, and Macedonian; she was thus of over 1,200 tons. (Cooper says more, “nearly double the tonnage of the Saratoga.”) She carried on her main-deck thirty long 24’s, fifteen in each broadside. She did not have a complete spar-deck; on her poop, which came forward to the mizzenmast, were two 32-pound (or possibly 42-pound) carronades and on her spacious top-gallant forecastle were four 32- (or 42-) pound carronades, and a long 24 on a pivot.3 She had aboard her a furnace for heating shot; eight or ten of which heated shot were found with the furnace.4 This was, of course, a perfectly legitimate advantage. The Linnet, Captain Daniel Pring, was a brig of the same size as the Ticonderoga, mounting 16 long 12’s. The Chubb and Finch, Lieutenants James McGhie and William Hicks, were formerly the American sloops Growler and Eagle, of 112 and 110 tons respectively. The former mounted ten 18-pound carronades and one long 6; the latter, six 18-pound carronades, four long 6’s, and one short 18. There were twelve gun-boats.5 Five of these were large, of about 70 tons each; three mounted a long 24 and a 32-pound carronade each; one mounted a long 18 and a 32-pound carronade; one a long 18 and a short 18. Seven were smaller, of about 40 tons each; three of these carried each a long 18, and four carried each a 32-pound carronade. There is greater difficulty in finding out the number of men in the British fleet. American historians are unanimous in stating it at from 1,000 to 1,100; British historians never do any thing but copy James blindly. Midshipman Lea of the Confiance, in a letter (already quoted) published in the “London Naval Chronicle,” vol. xxxii, p. 292, gives her crew as 300; but more than this amount of dead and prisoners were taken out of her. The number given her by Commander Ward in his “Naval Tactics,” is probably nearest right—325.6 The Linnet had about 125 men, and the Chubb and Finch about 50 men each. According to Admiral Paulding (given by Lossing, in his “Field-Book of the War of 1812,” p. 868) their gun-boats averaged 50 men each. This is probably true, as they were manned largely by soldiers, any number of whom could be spared from Sir George Prevost’s great army; but it may be best to consider the large ones as having 41, and the small 26 men, which were the complements of the American gun-boats of the same sizes.

The following, then, is the force of

In all, 16 vessels, of about 2,402 tons, with 937 men7 and a total of 92 guns, throwing at a broadside 1,192 lbs., 660 from long and 532 from short pieces.

These are widely different from the figures that appear in the pages of most British historians, from Sir Archibald Alison down and up. Thus, in the “History of the British Navy,” by C. D. Yonge (already quoted), it is said that on Lake Champlain “our (the British) force was manifestly and vastly inferior,*** their (the American) broadside outweighing ours in more than the proportion of three to two, while the difference in their tonnage and in the number of their crews was still more in their favor.” None of these historians, or quasihistorians, have made the faintest effort to find out the facts for themselves, following James’ figures with blind reliance, and accordingly it is only necessary to discuss the latter. This reputable gentleman ends his account (“Naval Occurrences,” p. 424) by remarking that Macdonough wrote as he did because “he knew that nothing would stamp a falsehood with currency equal to a pious expression,*** his falsehoods equalling in number the lines of his letter.” These remarks are interesting as showing the unbiassed and truthful character of the author, rather than for any particular weight they will have in influencing any one’s judgment on Commodore Macdonough. James gives the engaged force of the British as “8 vessels, of 1,426 tons, with 537 men, and throwing 765 lbs. of shot.” To reduce the force down to this, he first excludes the Finch, because she “grounded opposite an American battery before the engagement commenced,” which reads especially well in connection with Capt. Pring’s official letter: “Lieut Hicks, of the Finch, had the mortification to strike on a reef of rocks to the eastward of Crab Island about the middle of the engagement.8 What James mean cannot be imagined; no stretch of language will convert “about the middle of” into “before.” The Finch struck on the reef in consequence of having been disabled and rendered helpless by the fire from the Ticonderoga. Adding her force to James’ statement (counting her crew only as he gives it), we get 9 vessels, 1,536 tons, 577 men, 849 lbs. of shot. James also excludes five gun-boats, because they ran away almost as soon as the action commenced (vol. vi, p. 501). This assertion is by no means equivalent to the statement in Captain Pring’s letter “that the flotilla of gun-boats had abandoned the object assigned to them,” and, if it was, it would not warrant his excluding the five gun-boats. Their flight may have been disgraceful, but they formed part of the attacking force nevertheless; almost any general could say that he had won against superior numbers if he refused to count in any of his own men whom he suspected of behaving badly. James gives his 10 gun-boats 294 men and 13 guns (two long 24’s, five long 18’s, six 32-pound carronades), and makes them average 45 tons; adding on the five he leaves out, we get 14 vessels, of 1,761 tons, with 714 men, throwing at a broadside 1,025 lbs. of shot (591 from long guns, 434 from carronades). But Sir George Prevost, in the letter already quoted, says there were 12 gun-boats, and the American accounts say more. Supposing the two gun-boats James did not include at all to be equal respectively to one of the largest and one of the smallest of the gun-boats as he gives them (“Naval Occurrences,” p. 417); that is, one to have had 35 men, a long 24, and a 32-pound carronade, the other, 25 men and a 32-pound carronade, we get for Downie’s force 16 vessels, of 1,851 tons, with 774 men, throwing at a broadside 1,113 lbs. of shot (615 from long guns, 498 from carronades). It must be remembered that so far I have merely corrected James by means of the authorities from which he draws his account—the official letters of the British commanders. I have not brought up a single American authority against him, but have only made such alterations as a writer could with nothing whatever but the accounts of Sir George Prevost and Captain Pring before him to compare with James. Thus it is seen that according to James himself Downie really had 774 men to Macdonough’s 882, and threw at a broadside 1,113 lbs. of shot to Macdonough’s 1,194 lbs. James says (“Naval Occurrences,” pp. 410, 413): “Let it be recollected, no musketry was employed on either side,” and “The marines were of no use, as the action was fought out of the range of musketry”; the 106 additional men on the part of the Americans were thus not of much consequence, the action being fought at anchor, and there being men enough to manage the guns and perform every other duty. So we need only attend to the broadside force. Here, then, Downie could present at a broadside 615 lbs. of shot from long guns to Macdonough’s 480, and 498 lbs. from carronades to Macdonough’s 714; or, he threw 135 lbs. of shot more from his long guns, and 216 less from his carronades. This is equivalent to Downie’s having seven long 18’s and one long 9, and Macdonough’s having one 24-pound and six 32-pound carronades. A 32-pound carronade is not equal to a long 18; so that even by James’ own showing Downie’s force was slightly the superior.

Thus far, I may repeat, I have corrected James solely by the evidence of his own side; now I shall bring in some American authorities. These do not contradict the British official letters, for they virtually agree with them; but they do go against James’ unsupported assertions, and, being made by naval officers of irreproachable reputation, will certainly outweigh them. In the first place, James asserts that on the main-deck of the Confiance but 13 guns were presented in broadside, two 32-pound carronades being thrust through the bridle- and two others through the stern-ports; so he excludes two of her guns from the broadside. Such guns would have been of great use to her at certain stages of the combat, and ought to be included in the force. But besides this the American officers positively say that she had a broadside of 15 guns. Adding these two guns, and making a trifling change in the arrangement of the guns in the row-galleys, we get a broadside of 1,192 lbs., exactly as I have given it above. There is no difficulty in accounting for the difference of tonnage as given by James and by the Americans, for we have considered the same subject in reference to the battle of Lake Erie. James calculates the American tonnage as if for sea-vessels of deep holds, while, as regards the British vessels, he allows for the shallow holds that all the lake craft had; that is, he gives in one the nominal, in the other the real, tonnage. This fully accounts for the discrepancy. It only remains to account for the difference in the number of men. From James we can get 772. In the first place, we can reason by analogy. I have already shown that, as regards the battle of Lake Erie, he is convicted (by English, not by American, evidence) of having underestimated Barclay’s force by about 25 per cent. If he did the same thing here, the British force was over 1,000 strong, and I have no doubt that it was. But we have other proofs. On p. 417 of the “Naval Occurrences” he says the complement of the four captured British vessels amounted to 420 men, of whom 54 were killed in action, leaving 366 prisoners, including the wounded. But the report of prisoners, as given by the American authorities, gives 369 officers and seamen unhurt or but slightly wounded, 57 wounded men paroled, and other wounded whose number was unspecified. Supposing this number to have been 82, and adding 54 dead, we would get in all 550 men for the four ships, the number I have adopted in my list. This would make the British wounded 129 instead of 116, as James says: but neither the Americans nor the British seem to have enumerated all their wounded in this fight. Taking into account all these considerations, it will be seen that the figures I have given are probably approximately correct, and, at any rate, indicate pretty closely the relative strength of the two squadrons. The slight differences in tonnage and crews (158 tons and 55 men, in favor of the British) are so trivial that they need not be taken into account, and we will merely consider the broadside force. In absolute weight of metal the two combatants were evenly matched—almost exactly;—but whereas from Downie’s broadside of 1,192 lbs. 660 were from long and 532 from short guns, of Macdonough’s broadside of 1,194 lbs., but 480 were from long and 714 from short pieces. The forces were thus equal, except that Downie opposed 180 lbs. from long guns to 182 from carronades; as if 10 long 18’s were opposed to ten 18-pound carronades. This would make the odds on their face about 10 to 9 against the Americans; in reality they were greater, for the possession of the Confiance was a very great advantage. The action is, as regards metal, the exact reverse of those between Chauncy and Yeo. Take, for example, the fight off Burlington on Sept. 28, 1813. Yeo’s broadside was 1,374 lbs. to Chauncy’s 1,288; but whereas only 180 of Yeo’s was from long guns, of Chauncy’s but 536 was from carronades. Chauncy’s fleet was thus much the superior. At least we must say this: if Macdonough beat merely an equal force, then Yeo made a most disgraceful and cowardly flight before an inferior foe; but if we contend that Macdonough’s force was inferior to that of his antagonist, then we must admit that Yeo’s was in like manner inferior to Chauncy’s. These rules work both ways. The Confiance was a heavier vessel than the Pike, presenting in broadside one long 24- and three 32-pound carronades more than the latter. James (vol. vi, p. 355) says: “The Pike alone was nearly a match for Sir James Yeo’s squadron,” and Brenton says (vol. ii, 503): “The General Pike was more than a match for the whole British squadron.” Neither of these writers means quite as much as he says, for the logical result would be that the Confiance alone was a match for all of Macdonough’s force. Still it is safe to say that the Pike gave Chauncy a great advantage, and that the Confiance made Downie’s fleet much superior to Macdonough’s.

Macdonough saw that the British would be forced to make the attack in order to get the control of the waters. On this long, narrow lake the winds usually blow pretty nearly north or south, and the set of the current is of course northward; all the vessels, being flat and shallow, could not beat to windward well, so there was little chance of the British making the attack when there was a southerly wind blowing. So late in the season there was danger of sudden and furious gales, which would make it risky for Downie to wait outside the bay till the wind suited him; and inside the bay the wind was pretty sure to be light and baffling. Young Macdonough (then but 28 years of age) calculated all these chances very coolly and decided to await the attack at anchor in Plattsburg Bay, with the head of his line so far to the north that it could hardly be turned; and then proceeded to make all the other preparations with the same foresight. Not only were his vessels provided with springs, but also with anchors to be used astern in any emergency. The Saratoga was further prepared for a change of wind, or for the necessity of winding ship, by having a kedge planted broad off on each of her bows, with a hawser and preventer hawser (hanging in bights under water) leading from each quarter to the kedge on that side. There had not been time to train the men thoroughly at the guns; and to make these produce their full effect the constant supervision of the officers had to be exerted. The British were laboring under this same disadvantage, but neither side felt the want very much, as the smooth water, stationary position of the ships, and fair range, made the fire of both sides very destructive.

Plattsburg Bay is deep and opens to the southward; so that a wind which would enable the British to sail up the lake would force them to beat when entering the bay. The east side of the mouth of the bay is formed by Cumberland Head; the entrance is about a mile and a half across, and the other boundary, southwest from the Head, is an extensive shoal, and a small, low island. This is called Crab Island, and on it was a hospital and one six-pounder gun, which was to be manned in case of necessity by the strongest patients. Macdonough had anchored in a north-and-south line a little to the south of the outlet of the Saranac, and out of range of the shore batteries, being two miles from the western shore. The head of his line was so near Cumberland Head that an attempt to turn it would place the opponent under a very heavy fire, while to the south the shoal prevented a flank attack. The Eagle lay to the north, flanked on each side by a couple of gun-boats; then came the Saratoga, with three gun-boats between her and the Ticonderoga, the next in line; then came three gunboats and the Preble. The four large vessels were at anchor; the galleys being under their sweeps and forming a second line about 40 yards back, some of them keeping their places and some not doing so. By this arrangement his line could not be doubled upon, there was not room to anchor on his broadside out of reach of his carronades, and the enemy was forced to attack him by standing in bows on.

The morning of September 11th opened with a light breeze from the northeast. Downie’s fleet weighed anchor at daylight, and came down the lake with the wind nearly aft, the booms of the two sloops swinging out to starboard. At half-past seven,9 the people in the ships could see their adversaries’ upper sails across the narrow strip of land ending in Cumberland Head, before the British doubled the latter. Captain Downie hove to with his four large vessels when he had fairly opened the Bay, and waited for his galleys to overtake him. Then his four vessels filled on the starboard tack and headed for the American line, going abreast, the Chubb to the north, heading well to windward of the Eagle, for whose bows the Linnet was headed, while the Confiance was to be laid athwart the hawse of the Saratoga; the Finch was to leeward with the twelve gun-boats, and was to engage the rear of the American line.

As the English squadron stood bravely in, young Macdonough, who feared his foes not at all, but his God a great deal, knelt for a moment, with his officers, on the quarter-deck; and then ensued a few minutes of perfect quiet, the men waiting with grim expectancy for the opening of the fight. The Eagle spoke first with her long 18’s, but to no effect, for the shot fell short. Then, as the Linnet passed the Saratoga, she fired her broadside of long 12’s, but her shot also fell short, except one that struck a hen-coop which happened to be aboard the Saratoga. There was a game cock inside, and, instead of being frightened at his sudden release, he jumped up on a gun-slide, clapped his wings, and crowed lustily. The men laughed and cheered; and immediately afterward Macdonough himself fired the first shot from one of the long guns. The 24-pound ball struck the Confiance near the hawse-hole and ranged the length of her deck, killing and wounding several men. All the American long guns now opened and were replied to by the British galleys.

The Confiance stood steadily on without replying. But she was baffled by shifting winds, and was soon so cut up, having both her port bow-anchors shot away, and suffering much loss, that she was obliged to port her helm and come to while still nearly a quarter of a mile distant from the Saratoga. Captain Downie came to anchor in grand style,—securing every thing carefully before he fired a gun, and then opening with a terribly destructive broadside. The Chubb and Linnet stood farther in, and anchored forward the Eagle’s beam. Meanwhile the Finch got abreast of the Ticonderoga, under her sweeps, supported by the gun-boats. The main fighting was thus to take place between the vans, where the Eagle, Saratoga, and six or seven gun-boats were engaged with the Chubb, Linnet, Confiance, and two or three gun-boats; while in the rear, the Ticonderoga, the Preble, and the other American galleys engaged the Finch and the remaining nine or ten English galleys. The battle at the foot of the line was fought on the part of the Americans to prevent their flank being turned, and on the part of the British to effect that object. At first the fighting was at long range, but gradually the British galleys closed up, firing very well. The American galleys at this end of the line were chiefly the small ones, armed with one 12-pounder apiece, and they by degrees drew back before the heavy fire of their opponents. About an hour after the discharge of the first gun had been fired the Finch closed up toward the Ticonderoga, and was completely crippled by a couple of broadsides from the latter. She drifted helplessly down the line and grounded near Crab Island; some of the convalescent patients manned the six-pounder and fired a shot or two at her, when she struck, nearly half of her crew being killed or wounded. About the same time the British gun-boats forced the Preble out of line, whereupon she cut her cable and drifted inshore out of the fight. Two or three of the British gun-boats had already been sufficiently damaged by some of the shot from the Ticonderoga’s long guns to make them wary; and the contest at this part of the line narrowed down to one between the American schooner and the remaining British gun-boats, who combined to make a most determined attack upon her. So hastily had the squadron been fitted out that many of the matches for her guns were at the last moment found to be defective. The captain of one of the divisions was a midshipman, but sixteen years old, Hiram Paulding. When he found the matches to be bad he fired the guns of his section by having pistols flashed at them, and continued this through the whole fight. The Ticonderoga’s commander, Lieut. Cassin, fought his schooner most nobly. He kept walking the taffrail amidst showers of musketry and grape, coolly watching the movements of the galleys and directing the guns to be loaded with canister and bags of bullets, when the enemy tried to board. The British galleys were handled with determined gallantry, under the command of Lieutenant Bell. Had they driven off the Ticonderoga they would have won the day for their side, and they pushed up till they were not a boat-hook’s length distant, to try to carry her by boarding; but every attempt was repulsed and they were forced to draw off, some of them so crippled by the slaughter they had suffered that they could hardly man the oars.

Meanwhile the fighting at the head of the line had been even fiercer. The first broadside of the Confiance, fired from 16 long 24’s, double shotted, coolly sighted, in smooth water, at point-blank range, produced the most terrible effect on the Saratoga. Her hull shivered all over with the shock, and when the crash subsided nearly half of her people were seen stretched on deck, for many had been knocked down who were not seriously hurt. Among the slain was her first lieutenant, Peter Gamble; he was kneeling down to sight the bow-gun, when a shot entered the port, split the quoin, and drove a portion of it against his side, killing him without breaking the skin. The survivors carried on the fight with undiminished energy. Macdonough himself worked like a common sailor, in pointing and handling a favorite gun. While bending over to sight it a round shot cut in two the spanker boom, which fell on his head and struck him senseless for two or three minutes; he then leaped to his feet and continued as before, when a shot took off the head of the captain of the gun and drove it in his face with such a force as to knock him to the other side of the deck. But after the first broadside not so much injury was done; the guns of the Confiance had been levelled to point-blank range, and as the quoins were loosened by the successive discharges they were not properly replaced, so that her broadsides kept going higher and higher and doing less and less damage. Very shortly after the beginning of the action her gallant captain was slain. He was standing behind one of the long guns when a shot from the Saratoga struck it and threw it completely off the carriage against his right groin, killing him almost instantly. His skin was not broken; a black mark, about the size of a small plate, was the only visible injury. His watch was found flattened, with its hands pointing to the very second at which he received the fatal blow. As the contest went on the fire gradually decreased in weight, the guns being disabled. The inexperience of both crews partly caused this. The American sailors overloaded their carronades so as to very much destroy the effect of their fire; when the officers became disabled, the men would cram the guns with shot till the last projected from the muzzle. Of course, this lessened the execution, and also gradually crippled the guns. On board the Confiance the confusion was even worse: after the battle the charges of the guns were drawn, and on the side she had fought one was found with a canvas bag containing two round of shot rammed home and wadded without any powder; another with two cartridges and no shot; and a third with a wad below the cartridge.

At the extreme head of the line the advantage had been with the British. The Chubb and Linnet had begun a brisk engagement with the Eagle and American gun-boats. In a short time the Chubb had her cable, bowsprit, and main-boom shot away, drifted within the American lines, and was taken possession of by one of the Saratoga’s midshipmen. The Linnet paid no attention to the American gun-boats, directing her whole fire against the Eagle, and the latter was, in addition, exposed to part of the fire of the Confiance. After keeping up a heavy fire for a long time her springs were shot away, and she came up into the wind, hanging so that she could not return a shot to the well-directed broadsides of the Linnet. Henly accordingly cut his cable, started home his topsails, ran down, and anchored by the stern between and inshore of the Confiance and Ticonderoga, from which position he opened on the Confiance. The Linnet now directed her attention to the American gun-boats, which at this end of the line were very well fought, but she soon drove them off, and then sprung her broadside so as to rake the Saratoga on her bows.

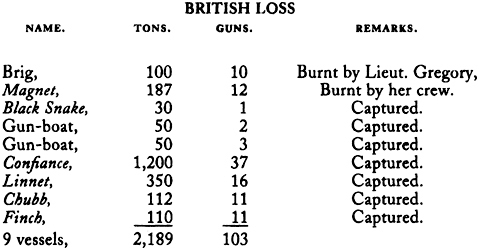

Macdonough by this time had his hands full, and his fire was slackening; he was bearing the whole brunt of the action, with the frigate on his beam and the brig raking him. Twice his ship had been set on fire by the hot shot of the Confiance; one by one his long guns were disabled by shot, and his carronades were either treated the same way or else rendered useless by excessive overcharging. Finally but a single carronade was left in the starboard batteries, and on firing it the naval-bolt broke, the gun flew off the carriage and fell down the main hatch, leaving the Commodore without a single gun to oppose to the few the Confiance still presented. The battle would have been lost had not Macdonough’s foresight provided the means of retrieving it. The anchor suspended astern of the Saratoga was let go, and the men hauled in on the hawser that led to the starboard quarter, bringing the ship’s stern up over the kedge. The ship now rode by the kedge and by a line that had been bent to a bight in the stream cable, and she was raked badly by the accurate fire of the Linnet. By rousing on the line the ship was it length got so far round that the aftermost gun of the port broadside bore on the Confiance. The men had been sent forward to keep as much out of harm’s way as possible, and now some were at once called back to man the piece, which then opened with effect. The next gun was treated in the same manner; but the ship now hung and would go no farther round. The hawser leading from the port quarter was then got forward under the bows and passed aft to the starboard quarter, and a minute afterward the ship’s whole port battery opened with fatal effect. The Confiance meanwhile had also attempted to round. Her springs, like those of the Linnet, were on the starboard side, and so of course could not be shot away as the Eagle’s were; but, as she had nothing but springs to rely on, her efforts did little beyond forcing her forward, and she hung with her head to the wind. She had lost over half of her crew,10 most of her guns on the engaged side were dismounted, and her stout masts had been splintered till they looked like bundles of matches; her sails had been torn to rags, and she was forced to strike, about two hours after she had fired the first broadside. Without pausing a minute the Saratoga again hauled on her starboard hawser till her broadside was sprung to bear on the Linnet, and the ship and brig began a brisk fight, which the Eagle from her position could take no part in, while the Ticonderoga was just finishing up the British galleys. The shattered and disabled state of the Linnet’s masts, sails, and yards precluded the most distant hope of Capt. Pring’s effecting his escape by cutting his cable; but he kept up a most gallant fight with his greatly superior foe, in hopes that some of the gun-boats would come and tow him off, and dispatched a lieutenant to the Confiance to ascertain her state. The lieutenant returned with news of Capt. Downie’s death, while the British gun-boats had been driven half a mile off; and, after having maintained the fight single-handed for fifteen minutes, until, from the number of shot between wind and water, the water had risen a foot above her lower deck, the plucky little brig hauled down her colors, and the fight ended, a little over two hours and a half after the first gun had been fired. Not one of the larger vessels had a mast that would bear canvas, and the prizes were in a sinking condition. The British galleys drifted to leeward, none with their colors up; but as the Saratoga’s boarding-officer passed along the deck of the Confiance he accidentally ran against a lock-string of one of her starboard guns,11 and it went off. This was apparently understood as a signal by the galleys, and they moved slowly off, pulling but a very few sweeps, and not one of them hoisting an ensign.

On both sides the ships had been cut up in the most extraordinary manner; the Saratoga had 55 shot-holes in her hull, and the Confiance 105 in hers, and the Eagle and Linnet had suffered in proportion. The number of killed and wounded can not be exactly stated: it was probably about 200 on the American side, and over 300 on the British.12

Captain Macdonough at once returned the British officers their swords. Captain Pring writes: “I have much satisfaction in making you acquainted with the humane treatment the wounded have received from Commodore Macdonough; they were immediately removed to his own hospital on Crab Island, and furnished with every requisite. His generous and polite attention to myself, the officers, and men, will ever hereafter be gratefully remembered.” The effects of the victory were immediate and of the highest importance. Sir George Prevost and his army at once fled in great haste and confusion back to Canada, leaving our northern frontier clear for the remainder of the war; while the victory had a very great effect on the negotiations for peace.

In this battle the crews on both sides behaved with equal bravery, and left nothing to be desired in this respect; but from their rawness they of course showed far less skill than the crews of most of the American and some of the British ocean cruisers, such as the Constitution, United States, or Shannon, the Hornet, Wasp, or Reindeer. Lieut. Cassin handled the Ticonderoga, and Captain Pring the Linnet, with the utmost gallantry and skill, and, after Macdonough, they divide the honors of the day. But Macdonough in this battle won a higher fame than any other commander of the war, British or American. He had a decidedly superior force to contend against, the officers and men of the two sides being about on a par in every respect; and it was solely owing to his foresight and resource that we won the victory. He forced the British to engage at a disadvantage by his excellent choice of position; and he prepared beforehand for every possible contingency. His personal prowess had already been shown at the cost of the rovers of Tripoli, and in this action he helped fight the guns as ably as the best sailor. His skill, seamanship, quick eye, readiness of resource, and indomitable pluck, are beyond all praise. Down to the time of the Civil War he is the greatest figure in our naval history. A thoroughly religious man, he was as generous and humane as he was skilful and brave; one of the greatest of our sea-captains, he has left a stainless name behind him.

1815: THE BATTLE OF NEW ORLEANS

The war on land generally disastrous. British send great expedition against New Orleans • Jackson prepares for the defence of the city • Night attack on the British advance guard • Artillery duels • Great battle of January 8, 1815 • Slaughtering repulse of the main attack • Rout of the Americans on the right bank of the river • Final retreat of the British • Observations on the character of the troops and commanders engaged

While our navy had been successful, the war on land had been for us full of humiliation. The United States then formed but a loosely knit confederacy, the sparse population scattered over a great expanse of land. Ever since the Federalist party had gone out of power in 1800, the nation’s ability to maintain order at home and enforce respect abroad had steadily dwindled; and the twelve years’ nerveless reign of the Doctrinaire Democracy had left us impotent for attack and almost as feeble for defence. Jefferson, though a man whose views and theories had a profound influence upon our national life, was perhaps the most incapable Executive that ever filled the presidential chair; being almost purely a visionary, he was utterly unable to grapple with the slightest actual danger, and, not even excepting his successor, Madison, it would be difficult to imagine a man less fit to guide the state with honor and safety through the stormy times that marked the opening of the present century. Without the prudence to avoid war or the forethought to prepare for it, the Administration drifted helplessly into a conflict in which only the navy prepared by the Federalists twelve years before, and weakened rather than strengthened during the intervening time, saved us from complete and shameful defeat. True to its theories, the House of Virginia made no preparations, and thought the war could be fought by “the nation in arms”; the exponents of this particular idea, the militiamen, a partially armed mob, ran like sheep whenever brought into the field. The regulars were not much better. After two years of warfare, Scott records in his autobiography that there were but two books of tactics (one written in French) in the entire army on the Niagara frontier; and officers and men were on such a dead level of ignorance that he had to spend a month drilling all of the former, divided into squads, in the school of the soldier and school of the company.1 It is small wonder that such troops were utterly unable to meet the English. Until near the end, the generals were as bad as the armies they commanded, and the administration of the War Department continued to be a triumph of imbecility to the very last.2 With the exception of the brilliant and successful charge of the Kentucky mounted infantry at the battle of the Thames, the only bright spot in the war in the North was the campaign on the Niagara frontier during the summer of 1814; and even here, the chief battle, that of Lundy’s Lane, though reflecting as much honor on the Americans as on the British, was for the former a defeat, and not a victory, as most of our writers seem to suppose.

But the war had a dual aspect. It was partly a contest between the two branches of the English race, and partly a last attempt on the part of the Indian tribes to check the advance of the most rapidly growing one of these same two branches; and this last portion of the struggle, though attracting comparatively little attention, was really much the most far-reaching in its effect upon history. The triumph of the British would have distinctly meant the giving a new lease of life to the Indian nationalities, the hemming in, for a time, of the United States, and the stoppage, perhaps for many years, of the march of English civilization across the continent. The English of Britain were doing all they could to put off the day when their race would reach to a world-wide supremacy.

There was much fighting along our Western frontier with various Indian tribes; and it was especially fierce in the campaign that a backwoods general of Tennessee, named Andrew Jackson, carried on against the powerful confederacy of the Creeks, a nation that was thrust in like a wedge between the United States proper and their dependency, the newly acquired French province of Louisiana. After several slaughtering fights, the most noted being the battle of the Horse-shoe Bend, the power of the Creeks was broken for ever; and afterward, as there was much question over the proper boundaries of what was then the Latin land of Florida, Jackson marched south, attacked the Spaniards and drove them from Pensacola. Meanwhile the British, having made a successful and ravaging summer campaign through Virginia and Maryland, situated in the heart of the country, organized the most formidable expedition of the war for a winter campaign against the outlying land of Louisiana, whose defender Jackson of necessity became. Thus, in the course of events, it came about that Louisiana was the theatre on which the final and most dramatic act of the war was played.

* * *

Amid the gloomy, semi-tropical swamps that cover the quaking delta thrust out into the blue waters of the Mexican Gulf by the strong torrent of the mighty Mississippi, stood the fair, French city of New Orleans. Its lot had been strange and varied. Won and lost, once and again, in conflict with the subjects of the Catholic king, there was a strong Spanish tinge in the French blood that coursed so freely through the veins of its citizens; joined by purchase to the great Federal Republic, it yet shared no feeling with the latter, save that of hatred to the common foe. And now an hour of sore need had come upon the city; for against it came the red English, lords of fight by sea and land. A great fleet of war vessels—ships of the line, frigates and sloops—under Admiral Cochrane, was on the way to New Orleans, convoying a still larger fleet of troop ships, with aboard them some ten thousand fighting men, chiefly the fierce and hardy veterans of the Peninsular War,3 who had been trained for seven years in the stern school of the Iron Duke, and who were now led by one of the bravest and ablest of all Wellington’s brave and able lieutenants, Sir Edward Packenham.

On the 8th of December 1814, the foremost vessels, with among their number the great two-decker Tonnant, carrying the admiral’s flag, anchored off the Chandeleur Islands,4 and as the current of the Mississippi was too strong to be easily breasted, the English leaders determined to bring their men by boats through the bayous, and disembark them on the bank of the river ten miles below the wealthy city at whose capture they were aiming. There was but one thing to prevent the success of this plan, and that was the presence in the bayous of five American gun-boats, manned by a hundred and eighty men, and commanded by Lieutenant Comdg. Catesby Jones, a very shrewd fighter. So against him was sent Captain Nicholas Lockyer with forty-five barges, and nearly a thousand sailors and marines, men who had grown gray during a quarter of a century of unbroken ocean warfare. The gun-boats were moored in a head-and-stern line, near the Rigolets, with their boarding-nettings triced up, and every thing ready to do desperate battle; but the British rowed up with strong, swift strokes, through a murderous fire of great guns and musketry; the vessels were grappled amid fierce resistance; the boarding-nettings were slashed through and cut away; with furious fighting the decks were gained; and one by one, at push of pike and cutlass stroke, the gun-boats were carried in spite of their stubborn defenders; but not till more than one barge had been sunk, while the assailants had lost a hundred men, and the assailed about half as many.

There was now nothing to hinder the landing of the troops; and as the scattered transports arrived, the soldiers were disembarked, and ferried through the sluggish water of the bayous on small flat-bottomed craft; and finally, Dec. 23d, the advance guard, two thousand strong, under General Keane, emerged at the mouth of the canal Villeré, and camped on the bank of the river,5 but nine miles below New Orleans, which now seemed a certain prize, almost within their grasp.

Yet, although a mighty and cruel foe was at their very gates, nothing save fierce defiance reigned in the fiery creole hearts of the Crescent City. For a master-spirit was in their midst. Andrew Jackson, having utterly broken and destroyed the most powerful Indian confederacy that had ever menaced the Southwest, and having driven the haughty Spaniards from Pensacola, was now bending all the energies of his rugged intellect and indomitable will to the one object of defending New Orleans. No man could have been better fitted for the task. He had hereditary wrongs to avenge on the British, and he hated them with an implacable fury that was absolutely devoid of fear. Born and brought up among the lawless characters of the frontier, and knowing well how to deal with them, he was able to establish and preserve the strictest martial law in the city without in the least quelling the spirit of the citizens. To a restless and untiring energy he united sleepless vigilance and genuine military genius. Prompt to attack whenever the chance offered itself, seizing with ready grasp the slightest vantage-ground, and never giving up a foot of earth that he could keep, he yet had the patience to play a defensive game when it so suited him, and with consummate skill he always followed out the scheme of warfare that was best adapted to his wild soldiery. In after-years he did to his country some good and more evil; but no true American can think of his deeds at New Orleans without profound and unmixed thankfulness.

He had not reached the city till December 2d, and had therefore but three weeks in which to prepare the defence. The Federal Government, throughout the campaign, did absolutely nothing for the defence of Louisiana; neither provisions nor munitions of war of any sort were sent to it, nor were any measures taken for its aid.6 The inhabitants had been in a state of extreme despondency up to the time that Jackson arrived, for they had no one to direct them, and they were weakened by factional divisions7, but after his coming there was nothing but the utmost enthusiasm displayed, so great was the confidence he inspired, and so firm his hand in keeping down all opposition. Under his direction earthworks were thrown up to defend all the important positions, the whole population working night and day at them; all the available artillery was mounted, and every ounce of war material that the city contained was seized; martial law was proclaimed; and all general business was suspended, every thing being rendered subordinate to the one grand object of defence.

Jackson’s forces were small. There were two war vessels in the river. One was the little schooner Carolina, manned by regular seamen, largely New Englanders. The other was the newly built ship Louisiana, a powerful corvette; she had of course no regular crew, and her officers were straining every nerve to get one from the varied ranks of the maritime population of New Orleans; long-limbed and hard-visaged Yankees, Portuguese and Norwegian seamen from foreign merchantmen, dark-skinned Spaniards from the West Indies, swarthy Frenchmen who had served under the bold privateersman Lafitte,—all alike were taken; and all alike by unflagging exertions were got into shape for battle.8 There were two regiments of regulars, numbering together about eight hundred men, raw and not very well disciplined, but who were now drilled with great care and regularity. In addition to this Jackson raised somewhat over a thousand militiamen among the citizens. There were some Americans among them, but they were mostly French creoles,9 and one band had in its formation something that was curiously pathetic. It was composed of free men of color,10 who had gathered to defend the land which kept the men of their race in slavery; who were to shed their blood for the Flag that symbolized to their kind not freedom but bondage; who were to die bravely as freemen, only that their brethren might live on ignobly as slaves. Surely there was never a stranger instance than this of the irony of fate.

But if Jackson had been forced to rely only on these troops New Orleans could not have been saved. His chief hope lay in the volunteers of Tennessee, who, under their Generals, Coffee and Carroll, were pushing their toilsome and weary way toward the city. Every effort was made to hurry their march through the almost impassable roads, and at last, in the very nick of time, on the 23d of December, the day on which the British troops reached the riverbank, the vanguard of the Tennesseeans marched into New Orleans. Gaunt of form and grim of face; with their powder-horns slung over their buckskin shirts; carrying their long rifles on their shoulders and their heavy hunting-knives stuck in their belts; with their coon-skin caps and fringed leggings; thus came the grizzly warriors of the backwoods, the heroes of the Horse-Shoe Bend, the victors over Spaniard and Indian, eager to pit themselves against the trained regulars of Britain, and to throw down the gage of battle to the world-renowned infantry of the island English. Accustomed to the most lawless freedom, and to giving free rein to the full violence of their passions, defiant of discipline and impatient of the slightest restraint, caring little for God and nothing for man, they were soldiers who, under an ordinary commander, would have been fully as dangerous to themselves and their leaders as to their foes. But Andrew Jackson was of all men the one best fitted to manage such troops. Even their fierce natures quailed before the ungovernable fury of a spirit greater than their own; and their sullen, stubborn wills were bent at last before his unyielding temper and iron hand. Moreover, he was one of themselves; he typified their passions and prejudices, their faults and their virtues; he shared their hardships as if he had been a common private, and, in turn, he always made them partakers of his triumphs. They admired his personal prowess with pistol and rifle, his unswerving loyalty to his friends, and the relentless and unceasing war that he waged alike on the foes of himself and his country. As a result they loved and feared him as few generals have ever been loved or feared; they obeyed him unhesitatingly, they followed his lead without flinching or murmuring, and they ever made good on the field of battle the promise their courage held out to his judgment.

It was noon of December 23d when General Keane, with nineteen hundred men, halted and pitched his camp on the east bank of the Mississippi; and in the evening enough additional troops arrived to swell his force to over twenty-three hundred soldiers.11 Keane’s encampment was in a long plain, rather thinly covered with fields and farmhouses, about a mile in breadth, and bounded on one side by the river, on the other by gloomy and impenetrable cypress swamps; and there was no obstacle interposed between the British camp and the city it menaced.

At two in the afternoon word was brought to Jackson that the foe had reached the river bank, and without a moment’s delay the old backwoods fighter prepared to strike a rough first blow. At once, and as if by magic, the city started from her state of rest into one of fierce excitement and eager preparation. The alarm-guns were fired; in every quarter the war-drums were beaten; while, amid the din and clamor, all the regulars and marines, the best of the creole militia, and the vanguard of the Tennesseeans, under Coffee,—forming a total of a little more than two thousand men12—were assembled in great haste; and the gray of the winter twilight saw them, with Old Hickory at their head, marching steadily along the river bank toward the camp of their foes. Patterson, meanwhile, in the schooner Carolina, dropped down with the current to try the effect of a flank attack.

Meanwhile the British had spent the afternoon in leisurely arranging their camp, in posting the pickets, and in foraging among the farm-houses. There was no fear of attack, and as the day ended huge campfires were lit, at which the hungry soldiers cooked their suppers undisturbed. One division of the troops had bivouacked on the high levee that kept the waters from flooding the land near by; and about half past seven in the evening their attention was drawn to a large schooner which had dropped noiselessly down, in the gathering dusk, and had come to anchor a short distance off shore, the force of the stream swinging her broadside to the camp. 13 The soldiers crowded down to the water’s edge, and, as the schooner returned no answer to their hails, a couple of musket-shots were fired at her. As if in answer to this challenge, the men on shore heard plainly the harsh voice of her commander, as he sung out, “Now then, give it to them for the honor of America”; and at once a storm of grape hurtled into their ranks. Wild confusion followed. The only field-pieces with Keane were two light 3-pounders, not able to cope with the Carolina’s artillery; the rocket guns were brought up, but were speedily silenced; musketry proved quite as ineffectual; and in a very few minutes the troops were driven helter-skelter off the levee, and were forced to shelter themselves behind it, not without having suffered severe loss.14 The night was now as black as pitch; the embers of the deserted camp-fires, beaten about and scattered by the schooner’s shot, burned with a dull red glow; and at short intervals the darkness was momentarily lit up by the flashes of the Carolina’s guns. Crouched behind the levee, the British soldiers lay motionless, listening in painful silence to the pattering of the grape among the huts, and to the moans and shrieks of the wounded who lay beside them. Things continued thus till toward nine o’clock, when a straggling fire from the pickets gave warning of the approach of a more formidable foe. The American land-forces had reached the outer lines of the British camp, and the increasing din of the musketry, with ringing through it the whip-like crack of the Tennesseean rifles, called out the whole British army to the shock of a desperate and uncertain strife. The young moon had by this time struggled through the clouds, and cast on the battle-field a dim, unearthly light that but partly relieved the intense darkness. All order was speedily lost. Each officer, American or British, as fast as he could gather a few soldiers round him, attacked the nearest group of foes; the smoke and gloom would soon end the struggle, when, if unhurt, he would rally what men he could and plunge once more into the fight. The battle soon assumed the character of a multitude of individual combats, dying out almost as soon as they began, because of the difficulty of telling friend from foe, and beginning with ever-increasing fury as soon as they had ended. The clatter of the firearms, the clashing of steel, the rallying cries and loud commands of the officers, the defiant shouts of the men, joined to the yells and groans of those who fell, all combined to produce so terrible a noise and tumult that it maddened the coolest brains. From one side or the other bands of men would penetrate into the heart of the enemy’s lines, and would there be captured, or would cut their way out with the prisoners they had taken. There was never a fairer field for the fiercest personal prowess, for in the darkness the firearms were of little service, and the fighting was hand to hand. Many a sword, till then but a glittering toy, was that night crusted with blood. The British soldiers and the American regulars made fierce play with their bayonets, and the Tennesseeans, with their long hunting-knives. Man to man, in grimmest hate, they fought and died, some by bullet and some by bayonet-thrust or stroke of sword. More than one in his death agony slew the foe at whose hand he himself had received the mortal wound; and their bodies stiffened as they lay, locked in the death grip. Again the clouds came over the moon; a thick fog crept up from the river, wrapping from sight the ghastly havoc of the battle-field; and long before midnight the fighting stopped perforce, for the fog and the smoke and the gloom were such that no one could see a yard away. By degrees each side drew off.15 In sullen silence Jackson marched his men up the river, while the wearied British returned to their camp. The former had lost over two hundred,16 the latter nearly three hundred17 men; for the darkness and confusion that added to the horror, lessened the slaughter of the battle.

Jackson drew back about three miles, where he halted and threw up a long line of breastworks, reaching from the river to the morass; he left a body of mounted riflemen to watch the British. All the English troops reached the field on the day after the fight; but the rough handling that the foremost had received made them cautious about advancing. Moreover, the left division was kept behind the levee all day by the Carolina, which opened upon them whenever they tried to get away; nor was it till dark that they made their escape out of range of her cannon. Christmas-day opened drearily enough for the invaders. Although they were well inland, the schooner, by greatly elevating her guns, could sometimes reach them, and she annoyed them all through the day,18 and as the Americans had cut the levee in their front, it at one time seemed likely that they would be drowned out. However, matters now took a turn for the better. The river was so low that the cutting of the levee instead of flooding the plain19 merely filled the shrunken bayous, and rendered it easy for the British to bring up their heavy guns; and on the same day their trusted leader, Sir Edward Packenham, arrived to take command in person, and his presence gave new life to the whole army. A battery was thrown up during the two succeeding nights on the brink of the river opposite to where the Carolina lay; and at dawn a heavy cannonade of red-hot shot and shell was opened upon her from eleven guns and a mortar.20 She responded briskly, but very soon caught fire and blew up, to the vengeful joy of the troops whose bane she had been for the past few days. Her destruction removed the last obstacle to the immediate advance of the army; but that night her place was partly taken by the mounted riflemen, who rode down to the British lines, shot the sentries, engaged the out-posts, and kept the whole camp in a constant state of alarm.21

In the morning Sir Edward Packenham put his army in motion, and marched on New Orleans. When he had gone nearly three miles he suddenly, and to his great surprise, stumbled on the American army. Jackson’s men had worked like beavers, and his breastworks were already defended by over three thousand fighting men, 22 and by half a dozen guns, and moreover were flanked by the corvette Louisiana, anchored in the stream. No sooner had the heads of the British columns appeared than they were driven back by the fire of the American batteries; the field-pieces, mortars, and rocket guns were then brought up, and a sharp artillery duel took place. The motley crew of the Louisiana handled their long ship guns with particular effect; the British rockets proved of but little service,23 and after a stiff fight, in which they had two field-pieces and a light mortar dismounted,24 the British artillerymen fell back on the infantry. Then Packenham drew off his whole army out of cannon shot, and pitched his camp facing the intrenched lines of the Americans. For the next three days the British battalions lay quietly in front of their foe, like wolves who have brought to bay a gray boar, and crouch just out of reach of his tusks, waiting a chance to close in.

Packenham, having once tried the strength of Jackson’s position, made up his mind to breach his works and silence his guns with a regular battering train. Heavy cannon were brought up from the ships, and a battery was established on the bank to keep in check the Louisiana. Then, on the night of the last day of the year, strong parties of workmen were sent forward, who, shielded by the darkness, speedily threw up stout earthworks, and mounted therein fourteen heavy guns,25 to face the thirteen26 mounted in Jackson’s lines, which were but three hundred yards distant.

New Year’s day dawned very misty. As soon as the haze cleared off the British artillerymen opened with a perfect hail of balls, accompanied by a cloud of rockets and mortar shells. The Americans were taken by surprise, but promptly returned the fire, with equal fury and greater skill. Their guns were admirably handled; some by the cool New England seamen lately forming the crew of the Carolina, others by the fierce creole privateersmen of Lafitte, and still others by the trained artillerymen of the regular army. They were all old hands, who in their time had done their fair share of fighting, and were not to be flurried by any attack, however unexpected. The British cannoneers plied their guns like fiends, and fast and thick fell their shot; more slowly but with surer aim, their opponents answered them.27 The cotton bales used in the American embrasures caught fire, and blew up two powder caissons; while the sugar hogsheads of which the British batteries were partly composed were speedily shattered and splintered in all directions. Though the British champions fought with unflagging courage and untiring energy, and though they had long been versed in war, yet they seemed to lack the judgment to see and correct their faults, and most of their shot went too high.28 On the other hand, the old sea-dogs and trained regulars who held the field against them, not only fought their guns well and skilfully from the beginning, but all through the action kept coolly correcting their faults and making more sure their aim. Still, the fight was stiff and well contested. Two of the American guns were disabled and 34 of their men were killed or wounded. But one by one the British cannon were silenced or dismounted, and by noon their gunners had all been driven away, with the loss of 78 of their number.

The Louisiana herself took no part in this action. Patterson had previously landed some of her guns on the opposite bank of the river, placing them in a small redoubt. To match these the British also threw up some works and placed in them heavy guns, and all through New Year’s day a brisk cannonade was kept up across the river between the two water-batteries, but with very little damage to either side.

For a week after this failure the army of the invaders lay motionless facing the Americans. In the morning and evening the defiant, rolling challenge of the English drums came throbbing up through the gloomy cypress swamps to where the grim riflemen of Tennessee were lying behind their log breastworks, and both day and night the stillness was at short intervals broken by the sullen boom of the great guns which, under Jackson’s orders, kept up a never-ending fire on the leaguering camp of his foes.29 Nor could the wearied British even sleep undisturbed; all through the hours of darkness the outposts were engaged in a most harassing bush warfare by the backwoodsmen, who shot the sentries, drove in the pickets, and allowed none of those who were on guard a moment’s safety or freedom from alarm.30

But Packenham was all the while steadily preparing for his last and greatest stroke. He had determined to make an assault in force as soon as the expected reinforcements came up; nor, in the light of his past experience in conflict with foes of far greater military repute than those now before him, was this a rash resolve. He had seen the greatest of Napoleon’s marshals, each in turn, defeated once and again, and driven in headlong flight over the Pyrenees by the Duke of Wellington; now he had under him the flower of the troops who had won those victories; was it to be supposed for a moment that such soldiers31 who, in a dozen battles, had conquered the armies and captured the forts of the mighty French emperor, would shrink at last from a mud wall guarded by rough backwoodsmen? That there would be loss of life in such an assault was certain; but was loss of life to daunt men who had seen the horrible slaughter through which the stormers moved on to victory at Ciudad Rodrigo, Badajos, and San Sebastian? At the battle of Toulouse an English army, of which Packenham’s troops then formed part, had driven Soult from a stronger position than was now to be assailed, though he held it with a veteran infantry. Of a surety, the dashing general who had delivered the decisive blow on the stricken field of Salamanca,32 who had taken part in the rout of the ablest generals and steadiest soldiers of Continental Europe, was not the man to flinch from a motley array of volunteers, militia, and raw regulars, led by a grizzled old bush-fighter, whose name had never been heard of outside of his own swamps, and there only as the savage destroyer of some scarcely more savage Indian tribes.

Moreover, Packenham was planning a flank attack. Under his orders a canal was being dug from the head of the bayou up which the British had come, across the plain to the Mississippi. This was to permit the passage of a number of ships’ boats, on which one division was to be ferried to the opposite bank of the river, where it was to move up, and, by capturing the breastworks and waterbattery on the west side, flank Jackson’s main position on the east side.33 When this canal was nearly finished the expected reinforcements, two thousand strong, under General Lambert, arrived, and by the evening of the 7th all was ready for the attack, which was to be made at daybreak on the following morning. Packenham had under him nearly 10,00034 fighting men; 1,500 of these, under Colonel Thornton were to cross the river and make the attack on the west bank. Packenham himself was to superintend the main assault, on the east bank, which was to be made by the British right under General Gibbs, while the left moved forward under General Keane, and General Lambert commanded the reserve.35 Jackson’s36 position was held by a total of 5,500 men.37 Having kept a constant watch on the British, Jackson had rightly concluded that they would make the main attack on the east bank, and had, accordingly, kept the bulk of his force on that side. His works consisted simply of a mud breastwork, with a ditch in front of it, which stretched in a straight line from the river on his right across the plain, and some distance into the morass that sheltered his left. There was a small, unfinished redoubt in front of the breastworks on the river bank. Thirteen pieces of artillery were mounted on the works.38 On the right was posted the Seventh regular infantry, 430 strong; then came 740 Louisiana militia (both French creoles and men of color, and comprising 30 New Orleans riflemen, who were Americans), and 240 regulars of the Forty-fourth regiment; while the rest of the line was formed by nearly 500 Kentuckians and over 1,600 Tennesseeans, under Carroll and Coffee, with 250 creole militia in the morass on the extreme left, to guard the head of a bayou. In the rear were 230 dragoons, chiefly from Mississippi, and some other troops in reserve; making in all 4,700 men on the east bank. The works on the west bank were farther down stream, and were very much weaker. Commodore Patterson had thrown up a water-battery of nine guns, three long 24’s and six long 12’s, pointing across the river, and intended to take in flank any foe attacking Jackson. This battery was protected by some strong earthworks, mounting three field-pieces, which were thrown up just below it, and stretched from the river about 200 yards into the plain. The line of defence was extended by a ditch for about a quarter of a mile farther, when it ended, and from there to the morass, half a mile distant, there were no defensive works at all. General Morgan, a very poor militia office,39 was in command, with a force of 550 Louisiana militia, some of them poorly armed; and on the night before the engagement he was reinforced by 250 Kentuckians, poorly armed, undisciplined, and worn out with fatigue.40

All through the night of the 7th a strange, murmurous clangor arose from the British camp, and was borne on the moist air to the lines of their slumbering foes. The blows of pickaxe and spade as the ground was thrown up into batteries by gangs of workmen, the rumble of the artillery as it was placed in position, the measured tread of the battalions as they shifted their places or marched off under Thornton,—all these and the thousand other sounds of warlike preparation were softened and blended by the distance into one continuous humming murmur, which struck on the ears of the American sentries with ominous foreboding for the morrow. By midnight Jackson had risen and was getting every thing in readiness to hurl back the blow that he rightly judged was soon to fall on his front. Before the dawn broke his soldiery was all on the alert. The bronzed and brawny seamen were grouped in clusters around the great guns. The creole soldiers came of a race whose habit it has ever been to take all phases of life joyously; but that morning their gayety was tempered by a dark undercurrent of fierce anxiety. They had more at stake than any other men on the field. They were fighting for their homes; they were fighting for their wives and their daughters. They well knew that the men they were to face were very brave in battle and very cruel in victory,41 they well knew the fell destruction and nameless woe that awaited their city should the English take it at the sword’s point. They feared not for themselves; but in the hearts of the bravest and most careless there lurked a dull terror of what that day might bring upon those they loved.42 The Tennesseeans were troubled by no such misgivings. In saturnine, confident silence they lolled behind their mud walls, or, leaning on their long rifles, peered out into the gray fog with savage, reckless eyes. So, hour after hour, the two armies stood facing each other in the darkness, waiting for the light of day.

At last the sun rose, and as its beams struggled through the morning mist they glinted on the sharp steel bayonets of the English, where their scarlet ranks were drawn up in battle array, but four hundred yards from the American breastworks. There stood the matchless infantry of the island king, in the pride of their strength and the splendor of their martial glory; and as the haze cleared away they moved forward, in stern silence, broken only by the angry, snarling notes of the brazen bugles. At once the American artillery leaped into furious life; and, ready and quick, the more numerous cannon of the invaders responded from their hot, feverish lips. Unshaken amid the tumult of that iron storm the heavy red column moved steadily on toward the left of the American line, where the Tennesseeans were standing in motionless, grim expectancy. Three fourths of the open space was crossed, and the eager soldiers broke into a run. Then a fire of hell smote the British column. From the breastwork in front of them the white smoke curled thick into the air, as rank after rank the wild marksmen of the backwoods rose and fired, aiming low and sure. As stubble is withered by flame, so withered the British column under that deadly fire; and, aghast at the slaughter, the reeling files staggered and gave back, Packenham, fit captain for his valorous host, rode to the front, and the troops, rallying round him, sprang forward with ringing cheers. But once again the pealing rifle-blast beat in their faces; and the life of their dauntless leader went out before its scorching and fiery breath. With him fell the other general who was with the column, and all of the men who were leading it on; and, as a last resource, Keane brought up his stalwart Highlanders; but in vain the stubborn mountaineers rushed on, only to die as their comrades had died before them, with unconquerable courage, facing the foe, to the last. Keane himself was struck down; and the shattered wrecks of the British column, quailing before certain destruction, turned and sought refuge beyond reach of the leaden death that had overwhelmed their comrades. Nor did it fare better with the weaker force that was to assail the right of the American line. This was led by the dashing Colonel Rennie, who, when the confusion caused by the main attack was at its height, rushed forward with impetuous bravery along the river bank. With such headlong fury did he make the assault, that the rush of his troops took the outlying redoubt, whose defenders, regulars and artillerymen, fought to the last with their bayonets and clubbed muskets, and were butchered to a man. Without delay Rennie flung his men at the breastworks behind, and, gallantly leading them, sword in hand, he, and all around him, fell, riddled through and through by the balls of the riflemen. Brave though they were, the British soldiers could not stand against the singing, leaden hail, for if they stood it was but to die. So in rout and wild dismay they fled back along the river bank, to the main army. For some time afterward the British artillery kept up its fire, but was gradually silenced; the repulse was entire and complete along the whole line; nor did the cheering news of success brought from the west bank give any hope to the British commanders, stunned by their crushing overthrow.43

Meanwhile Colonel Thornton’s attack on the opposite side had been successful, but had been delayed beyond the originally intended hour. The sides of the canal by which the boats were to be brought through to the Mississippi caved in, and choked the passage,44 so that only enough got through to take over a half of Thornton’s force. With these, seven hundred in number,45 he crossed, but as he did not allow for the current, it carried him down about two miles below the proper landing-place. Meanwhile General Morgan, having under him eight hundred militia46 whom it was of the utmost importance to have kept together, promptly divided them and sent three hundred of the rawest and most poorly armed down to meet the enemy in the open. The inevitable result was their immediate rout and dispersion; about one hundred got back to Morgan’s lines. He then had six hundred men, all militia, to oppose to seven hundred regulars. So he stationed the four hundred best disciplined men to defend the two hundred yards of strong breastworks, mounting three guns, which covered his left; while the two hundred worst disciplined were placed to guard six hundred yards of open ground on his right, with their flank resting in air, and entirely unprotected.47 This truly phenomenal arrangement ensured beforehand the certain defeat of his troops, no matter how well they fought; but, as it turned out, they hardly fought at all. Thornton, pushing up the river, first attacked the breastwork in front, but was checked by a hot fire; deploying his men he then sent a strong force to march round and take Morgan on his exposed right flank.48 There, the already demoralized Kentucky militia, extended in thin order across an open space, outnumbered, and taken in flank by regular troops, were stampeded at once, and after firing a single volley they took to their heels.49 This exposed the flank of the better disciplined creoles, who were also put to flight; but they kept some order and were soon rallied.50 In bitter rage Patterson spiked the guns of his water-battery and marched off with his sailors, unmolested. The American loss had been slight, and that of their opponents not heavy, though among their dangerously wounded was Colonel Thornton.

This success, though a brilliant one, and a disgrace to the American arms, had no effect on the battle. Jackson at once sent over reinforcements under the famous French general, Humbert, and preparations were forthwith made to retake the lost position. But it was already abandoned, and the force that had captured it had been recalled by Lambert, when he found that the place could not be held without additional troops.51 The total British loss on both sides of the river amounted to over two thousand men, the vast majority of whom had fallen in the attack on the Tennesseeans, and most of the remainder in the attack made by Colonel Rennie. The Americans had lost but seventy men, of whom but thirteen fell in the main attack. On the east bank, neither the creole militia nor the Forty-fourth regiment had taken any part in the combat.

The English had thrown for high stakes and had lost every thing, and they knew it. There was nothing to hope for left. Nearly a fourth of their fighting men had fallen; and among the officers the proportion was far larger. Of their four generals, Packenham was dead, Gibbs dying, Keane disabled, and only Lambert left. Their leader, the ablest officers, and all the flower of their bravest men were lying, stark and dead, on the bloody plain before them; and their bodies were doomed to crumble into mouldering dust on the green fields where they had fought and had fallen. It was useless to make another trial. They had learned to their bitter cost, that no troops, however steady, could advance over open ground against such a fire as came from Jackson’s lines. Their artillerymen had three times tried conclusions with the American gunners, and each time they had been forced to acknowledge themselves worsted. They would never have another chance to repeat their flank attack, for Jackson had greatly strengthened and enlarged the works on the west bank, and had seen that they were fully manned and ably commanded. Moreover, no sooner had the assault failed, than the Americans again began their old harassing warfare. The heaviest cannon, both from the breastwork and the water-battery, played on the British camp, both night and day, giving the army no rest, and the mounted riflemen kept up a trifling, but incessant and annoying, skirmishing with their pickets and outposts.