From Theodore Roosevelt: An Autobiography

1 . In the Naval Archives (“Masters’-Commandant Letters,” 1814, 1, No. 134) is a letter from Macdonough in which he states that the Saratoga is intermediate in size between the Pike, of 875, and the Madison, of 593 tons; this would make her 734. The Eagle was very nearly the size of the Lawrence or Niagara, on Lake Erie. The Ticonderoga was originally a small steamer, but Commodore Macdonough had her schooner-rigged, because he found that her machinery got out of order on almost every trip that she took. Her tonnage is only approximately known, but she was of the same size as the Linnet.

2 . In the Naval Archives are numerous letters from Macdonough, in which he states continually that, as fast as they arrive, he substitutes sailors for the soldiers with which the vessels were originally manned. Men were continually being sent ashore on account of sickness. In the Bureau of Navigation is the log-book of “sloop-of-war Surprise, Captain Robert Henly” (Surprise was the name the Eagle originally went by). It mentions from time to time that men were buried and sent ashore to the hospital (five being sent ashore on September 2d); and finally mentions that the places of the absent were practially filled by a draft of 21 soldiers, to act as marines. The notes on the day of battle are very brief.

3 . This is her armament as given by Cooper, on the authority of Lieutenant E. A. F. Lavallette, who was in charge of her for three months, and went aboard her ten minutes after the Linnet struck.

4 . James stigmatizes the statement of Commodore Macdonough about the furnace as “as gross a falsehood as ever was uttered”; but he gives no authority for the denial, and it appears to have been merely an ebullition of spleen on his part. Every American officer who went aboard the Confiance saw the furnace and the hot shot.

5 . Letter of General George Prevost, Sept. 11, 1814. All the American accounts say 13; the British official account had best be taken. James says only ten, but gives no authority; he appears to have been entirely ignorant of all things connected with this action.

6 . James gives her but 270 men,—without stating his authority.

9 . The letters of the two commanders conflict a little as to time, both absolutely and relatively. Pring says the action lasted two hours and three quarters; the American accounts, two hours and twenty minutes. Pring says it began at 8:00; Macdonough says a few minutes before nine, etc. I take the mean time.

10 . Midshipman Lee, in his letter already quoted, says “not five men were left unhurt”; this would of course include bruises, etc., as hurts.

11 . A sufficient commentary, by the way, on James’ assertion that the guns of the Confiance had to be fired by matches, as the gun-locks did not fit!

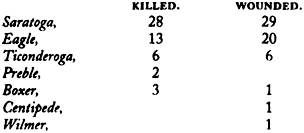

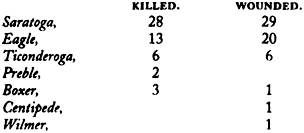

A total of 52 killed and 58 wounded; but the latter head apparently only included those who had to go to the hospital. Probably about 90 additional were more or less slightly wounded. Captain Pring, in his letter of Sept. 12th, says the Confiance had 41 killed and 40 wounded; the Linnet, 10 killed and 14 wounded; the Chubb, 6 killed and 16 wounded; the Finch, 2 wounded: in all, 57 killed and 72 wounded. But he adds “that no opportunity has offered to muster* * * this is the whole as yet ascertained to be killed or wounded.” The Americans took out 180 dead and wounded from the Confiance, 50 from the Linnet, and 40 from the Chubb and Finch, in all, 270. James (“Naval Occurrences,” p. 412) says the Confiance had 83 wounded. As Captain Pring wrote his letter in Plattsburg Bay the day after the action, he of course could not give the loss aboard the British gun-boats; so James at once assumed that they suffered none. As well as could be found out they had between 50 and 100 killed and wounded. The total British loss was between 300 and 400, as nearly as can be ascertained. For this action, as already shown, James is of no use whatever. Compare his statements, for example, with those of Midshipman Lee, in the “Naval Chronicle.” The comparative loss, as a means of testing the competitive prowess of the combatants, is not of much consequence in this case, as the weaker party in point of force conquered.

1815: The Battle of New Orleans

1 . “Memoirs of Lieutenant-General Scott,” written by himself (2 vols., New York, 1864), i, p. 115.

2 . Monroe’s biographer (see “James Monroe,” by Daniel C. Gilman, Boston, 1883, p. 123) thinks I made a good Secretary of War; I think he was as much a failure as his predecessors, and a harsher criticism could not be passed on him. Like the other statesmen of his school, he was mighty in word and weak in action; bold to plan but weak to perform. As an instance, contrast his fiery letters to Jackson with the fact that he never gave him a particle of practical help.

3 . “The British infantry embarked at Bordeaux, some for America, some for England.” (“History of the War in the Peninsula,” by Major-General Sir W.F.P. Napier, K.C.B. New edition. New York, 1882, vol. v, p. 200.) For discussion of numbers, see farther on.

5 . Letter of Major-General John Keane, Dec. 26, 1814.

6 . “Historical Memoir of the War in West Florida and Louisiana” (by Major A. Lacarriex Latour, translated from the French by H. P. Nugent, Philadelphia, 1816), p. 66.

8 . Letter of Commodore Daniel G. Patterson, Dec. 20, 1814.

11 . James (“Military Occurrences of the Late War,” by Wm. James, London, 1818), vol. ii, p. 362, says 2,050 rank and file; the English returns, as already explained, unlike the French and American, never included officers, sergeants, drummers, artillerymen, or engineers, but only “sabres and bayonets” (Napier, iv, 252). At the end of Napier’s fourth volume is given the “morning state” of Wellington’s forces on April 10, 1814. This shows 56,030 rank and file and 7,431 officers, sergeants, and trumpeters or drummers; or, in other words, to get at the real British force in an action, even supposing there are no artillerymen or engineers present, 13 per cent must be added to the given number, which includes only rank and file. Making this addition, Keane had 2,310 men. The Americans greatly overestimated his force, Latour making it 4,980.

12 . General Jackson, in his official letter, says only 1,500; but Latour, in a detailed statement, makes 2,024; exclusive of 107 Mississippi dragoons who marched with the column, but being on horseback had to stay behind, and took no part in the action. Keane thought he had been attacked by 5,000 men.

13 . I have taken my account of the night action chiefly from the work of an English soldier who took part in it; Ensign (afterward Chaplain-General) H. R. Gleig’s “Narrative of the Campaigns of the British Army at Washington, Baltimore, and New Orleans.” (New edition, Philadelphia, 1821, pp. 286–300.)

14 . General Keane, in his letter, writes that the British suffered but a single casualty; Gleig, who was present, says (p. 288): “The deadly shower of grape swept down numbers in the camp.”

15 . Keane writes: “The enemy thought it prudent to retire, and did not again dare to advance. It was now 12 o’clock, and the firing ceased on both sides”; and Jackson: “We should have succeeded … in capturing the enemy, had not a thick fog, which arose about (?) o’clock, occasioned some confusion.… I contented myself with lying on the field that night.” Jackson certainly failed to capture the British; but equally certainly damaged them so as to arrest their march till he was in condition to meet and check them.

16 . 24 killed, 115 wounded, 74 missing.

17 . 46 killed, 167 wounded, 64 missing. I take the official return for each side, as authority for the respective force and loss.

18 . “While sitting at table, a loud shriek was heard.… A shot had taken effect on the body of an unfortunate soldier … who was fairly cut in two at the lower portion of the belly!” (Gleig, p. 306.)

20 . Gleig, 307. The Americans thought the battery consisted of 5 18- and 12-pounders; Gleig says 9 field-pieces (9- and 6-pounders), 2 howitzers, and a mortar.

22 . 3,282 men in all, according to the Adjutant-General’s return for Dec. 28, 1814.

24 . Gleig, 314. The official returns show a loss of 18 Americans and 58 British, the latter suffering much less than Jackson supposed. Lossing, in his “Field-Book of the War of 1812,” not only greatly overestimates the British loss, but speaks as if this was a serious attack, which it was not. Packenham’s army, while marching, unexpectedly came upon the American intrenchment, and recoiled at once, after seeing that his field-pieces were unable to contend with the American artillery.

25 . 10 long 18’s and 4 24-pound carronades (James, ii, 368). Gleig says (p. 318), “6 batteries mounting 30 pieces of heavy cannon.” This must include the “brigade of field-pieces” of which James speaks. 9 of these, 9- and 6-pounders, and 2 howitzers, had been used in the attack on the Carolina; and there were also 2 field-mortars and 2 3-pounders present; and there must have been 1 other field-piece with the army, to make up the 30 of which Gleig speaks.

26 . viz.: 1 long 32, 3 long 24’s, 1 long 18, 3 long 12’s, 3 long 6’s, a 6-inch howitzer, and a small carronade (Latour, 147); and on the same day Patterson had in his water-battery 1 long 24 and 2 long 12’s (see his letter of Jan. 2d), making a total of 16 American guns.

27 . The British historian, Alison, says (“History of Europe,” by Sir Archibald Alison, 9th edition, Edinburgh and London, 1852, vol. xii, p. 141): “It was soon found that the enemy’s guns were so superior in weight and number, that nothing was to be expected from that species of attack.” As shown above, at this time Jackson had on both sides of the river 16 guns; the British, according to both James and Gleig, between 20 and 30. Jackson’s long guns were 1 32, 4 24’s, 1 18, 5 12’s, and 3 6’s, throwing in all 224 pounds; Packenham had 10 long 18’s, 2 long 3’s, and from 6 to 10 long 9’s and 6’s, thus throwing between 228 and 258 pounds of shot; while Jackson had but 1 howitzer and 1 carronade to oppose 4 carronades, 2 howitzers, 2 mortars, and a dozen rocket guns; so in both number and weight of guns the British were greatly superior.

28 . In strong contrast to Alison, Admiral Codrington, an eyewitness, states the true reason of the British failure: (“Memoir of Admiral Sir Edward Codrington,” by Lady Bourchier, London, 1873, vol. i, p. 334.) “On the 1st we had our batteries ready, by severe labor, in situation, from which the artillery people were, as a matter of course, to destroy and silence the opposing batteries, and give opportunity for a well-arranged storm. But, instead, not a gun of the enemy appeared to suffer, and our own firing too high was not discovered till” too late. “Such a failure in this boasted arm was not to be expected, and I think it a blot on the artillery escutcheon.”

31 . Speaking of Soult’s overthrow a few months previous to this battle, Napier says (v, 209): “He was opposed to one of the greatest generals of the world, at the head of unconquerable troops. For what Alexander’s Macedonians were at Arbela, Hannibal’s Africans at Cannæ, Cæsar’s Romans at Pharsalia, Napoleon’s Guards at Austerlitz—such were Wellington’s British soldiers at this period.… Six years of uninterrupted success had engrafted on their natural strength and fierceness a confidence that made them invincible.”

32 . It was about 5 o’clock when Packenham fell upon Thomiéres.… From the chief to the lowest soldier, all [of the French] felt that they were lost, and in an instant Packenham, the most frank and gallant of men, commenced the battle. The British columns formed lines as they marched, and the French gunners, standing up manfully for the honor of their country, sent showers of grape into the advancing masses, while a crowd of light troops poured in a fire of musketry, under cover of which the main body endeavored to display a front. But, bearing onwards through the skirmishers with the might of a giant, Packenham broke the half-formed lines into fragments, and sent the whole in confusion upon the advancing supports.… Packenham, bearing onwards with conquering violence,… formed one formidable line two miles in advance of where Packenham had first attacked; and that impetuous officer, with unmitigated strength, still pressed forward, spreading terror and disorder on the enemy’s left.” (Napier, iv, 57, 58, 59.)

33 . “A particular feature in the assault was our cutting a canal into the Mississippi.… to convey a force to the right bank, which … might surprise the enemy’s batteries on that side. I do not know how far this measure was relied on by the general, but, as he ordered and made his assault at daylight, I imagine he did not place much dependence upon it.” (Codrington, i, 335.)

34 . James (ii, 373) says the British “rank and file” amounted to 8,153 men, including 1,200 seamen and marines. The only other place where he speaks of the latter is in recounting the attack on the right bank, when he says “about 200” were with Thornton, while both the admirals, Cochrane and Codrington, make the number 300; so he probably underestimates their number throughout, and at least 300 can be added, making 1,500 sailors and marines, and a total of 8,453. This number is corroborated by Major McDougal, the officer who received Sir Edward’s body in his arms when he was killed; he says (as quoted in the “Memoirs of British Generals Distinguished During the Peninsular War,” by John William Cole, London, 1856, vol. ii, p. 364) that after the battle and the loss of 2,036 men, “we had still an effective force of 6,400,” making a total before the attack of 8,436 rank and file. Calling it 8,450, and adding (see ante, note 10) 13.3 per cent. for the officers, sergeants, and trumpeters, we get about 9,600 men.

35 . Letter of Major-General John Lambert to Earl Bathurst, Jan. 10, 1815.

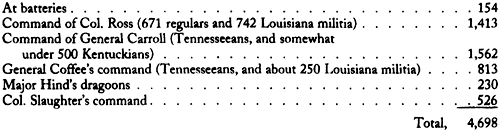

36 . 4,698 on the east bank, according to the official report of Adjutant-General Robert Butler, for the morning of January 8th. The details are as follow:

These figures tally almost exactly with those given by Major Latour, except that he omits all reference to Col. Slaughter’s command, thus reducing the number to about 4,100. Nor can I anywhere find any allusion to Slaughter’s command as taking part in the battle; and it is possible that these troops were the 500 Kentuckians ordered across the river by Jackson; in which case his whole force but slightly exceeded 5,000 men.

On the west bank there were 546 Louisiana militia—260 of the First regiment, 176 of the Second, and 110 of the Sixth. Jackson had ordered 500 Kentucky troops to be sent to reinforce them; only 400 started, of whom but 180 had arms. Seventy more received arms from the Naval Arsenal; and thus a total of 250 armed men were added to the 546 already on the west bank.

37 . Two thousand Kentucky militia had arrived, but in wretched plight; only 500 had arms, though pieces were found for about 250 more; and thus Jackson’s army received an addition of 750 very badly disciplined soldiers.

“Hardly one third of the Kentucky troops, so long expected, are armed, and the arms they have are not fit for use.” (Letter of Gen. Jackson to the Secretary of War, Jan. 3d.)

38 . Almost all British writers underestimate their own force and enormously magnify that of the Americans. Alison, for example, quadruples Jackson’s relative strength, writing: “About 6,000 combatants were on the British side; a slender force to attack double their number, intrenched to the teeth in works bristling with bayonets and loaded with heavy artillery.” Instead of double, he should have said half; the bayonets only “bristled” metaphorically, as less than a quarter of the Americans were armed with them; and the British breaching batteries had a heavier “load” of artillery than did the American lines. Gleig says that “to come nearer the truth” he “will choose a middle course, and suppose their whole force to be about 25,000 men” (p. 325). Gleig, by the way, in speaking of the battle itself, mentions one most startling evolution of the Americans, namely, that “without so much as lifting their faces above the ramparts, they swung their firelocks by one arm over the wall and discharged them” at the British. If any one will try to perform this feat, with a long, heavy rifle held in one hand, and with his head hid behind a wall, so as not to see the object aimed at, he will get a good idea of the likelihood of any man in his senses attempting it.

39 . He committed every possible fault, except showing lack of courage. He placed his works at a very broad instead of at a narrow part of the plain, against the advice of Latour, who had Jackson’s approval (Latour, 167). He continued his earthworks but a very short distance inland, making them exceedingly strong in front, and absolutely defenceless on account of their flanks being unprotected. He did not mount the lighter guns of the water-battery on his lines, as he ought to have done. Having a force of 800 men, too weak anyhow, he promptly divided it; and, finally, in the fight itself, he stationed a small number of absolutely raw troops in a thin line on the open, with their flank in air; while a much larger number of older troops were kept to defend a much shorter line, behind a strong breastwork, with their flanks covered.