Color Continuity and Change in Korean Culture

Key-Sook Geum and Hyun Jung

Chapter Summary. Color usage characterizes a specific society or group and playsan important role in enabling us to understand how people who belong to that group experience and use colors. Accordingly, just as the meaning of a word is understood through cultural context rather than only through a dictionary definition, the meaning or value of color used by a specific group also needs to be understood in a cultural context of continuity and change. For example, wearing white in the rites of both birth and death is a very specific characteristic of Korean traditional culture but has distinct symbolic meaning in each rite. Knowing the uses and meanings of colors within a specific culture provides an opportunity to understand the culture and helps ease mutual communication by enabling an understanding of the way of thinking of that people.

Color is affected by philosophy, religion, custom, and the natural environment within a society and is used as a sign that signifies concrete or abstract objects or ideas. To analyze and interpret the characteristics of colors being used in a culture and effectively apply those to actual designs, it is necessary to simultaneously consider specific characteristics related to ethnic sentiment and historical background and its modern interpretation, as well as the common universality of being human. For this, an objective knowledge of the relevant culture, as well as both a general and a specialized understanding of the culture, is required (Zollinger 1999: 197).

However, according to McCool (2008: 206), in the past, studies of color in culture often emphasized the negative implications of color within highly contextualized cultural events. For example, when red symbolizes communism and white means death, using these colors within a certain culture attracts attention and entails risk. Such implications may present limitations in the understanding of universal color prototypes that are used in modern society. As common associations derived from the affective meaning of colors in nature come into play as a basis for color symbolism formed by the influence of systems of thought such as philosophy and religion in a certain group, responses to colors may be universal and transcend cultural borders and cultural differences (Mahnke 1996: 17). In addition, changes in the sociocultural environment, such as the inflow of foreign cultures, influence of color trends and preferences, political revolution, and technology innovation, which often occur in our diverse and networked modern society, may bring changes to traditional symbols and meanings of colors and their values.

In this study we examine the properties, meanings, and symbols of the colors found in Korean traditional culture, and explore their continued use and transformation in contemporary applications. Investigating the meanings and symbolism of colors reflected in traditional rites and social systems will help us to understand the traditional consciousness of colors based on historical background or thoughts. In addition, examples of color phenomena found throughout current Korean society will help identify significance and interpretation of colors in contemporary Korean society.

KOREAN TRADITIONAL CULTURE AND CONSCIOUSNESS OF COLOR

Historical Background of Korean Culture

Korean traditional culture, handed down through shifting dynasties for 5,000 years, can be classified into three periods: before Samguksidae (before the fourth century), from Samguksidae to Goryeo Dynasty (the fourth century–1392), and Joseon Dynasty (1392–1910) (Park 2004: 313–15). By and large, systems of religion and thought such as Yin-Yang and the Five Elements, Buddhism, and Confucianism, pervasive in the Asian cultural area, have had a strong influence on Korean traditional culture across these three periods.

However, as Western religions and cultures were introduced after the opening of a port in the late Joseon period (1873), innovations and changes in the way of thinking came to the traditional society and culture, and this brought about changes in living modes, such as in costume and residential space. The Korean War that occurred in 1950 devastated Korean society and the ideological antagonism dividing Korea into the South and the North became a factor in determining the specific political environment of Korean society. As economic development policies in the 1960s and booming exports of construction projects in the 1970s created economic growth, traditional culture, long ignored, began to attract interest. The successful holding of international events such as the Asian Games and the Olympic Games in the 1980s accelerated the globalization of Korean society, and also enhanced the recognition of Korean traditional culture both within and outside of Korea.

As Korean society achieved rapid economic growth and active international exchanges with the conversion to the information society, an attitude of acceptance of foreign cultures shifted to one of researching and developing a rich cultural heritage. Korean people began to gain a new understanding of their traditional culture, and came to have pride as citizens of culture. Furthermore, in the late twentieth century, the so-called Hallyu (Korean wave) phenomenon emerged in international society, including Asia, and Korea grew to become a cultural leader.

Color Consciousness in Korean Traditional Culture

According to Jeong (2001: 170–72), color consciousness involves thoughts and theories of color and the psychological response to color formed historically and socially. Park (2004: 313) regarded color consciousness as one of the important factors mediating various types of social communications between class and class, and stratum and stratum, rather than between individual and individual.

Previous studies regarding Korean color consciousness (Eum and Chae 2006; Lee 2009; Seo 2009) regard Korean traditional color consciousness as having formed primarily under the influence of Yin-Yang and the Five Elements, Naturalism, Buddhism, and Confucianism. In particular, according to Park (2004: 313–33) who studied color consciousness in Korean traditional culture, the color culture before Samguksidae based on myths and being a process of giving charmed meanings to natural colors, is characterized by the stress on the symbolism of the color white as it related to the harvest ceremony, with the sun being the god. The color culture from Samguksidae to Goryeo Dynasty, found in ancient tomb murals or religious buildings, reflected Yin-Yang and the Five Elements and the religious belief and doctrines of Buddhism. In the Joseon period Confucianism was the state religion, and the use of color was greatly regulated to establish social systems such as political class or social status. Therefore, this period is characterized by the use of symbolic colors with compound meanings.

The use of colors in the long history of Korea can be summarized as having two main characteristics: One is a preference for white and natural colors that were not bleached or dyed, and the other is the harmonious use of primary colors. Examples of the former are a preference for white as a dominant color in casual clothing regardless of status, and the use of neutral colors for plaster and earthen walls of private houses, while examples of the latter include strong contrasts of primary colors and saekdong, which are multicolored stripes used in clothing, and dancheong, which is multicolored paintwork of the buildings in palaces and temples (Plate 18).

From ancient times, white appeared in myths regarding the foundation of the nation, and Koreans preferred to wear white clothing, to the extent that they were called “white clad folk.” In general, white represents truth and light, away from dirtiness. White symbolizes the starting point, the origin, and the root of things. As the anthropologist Turner (1975: 168–69) wrote, white is the most basic symbol to human beings; indeed, white was favored in many cultural spheres who worshipped the sun. However, it is understood that the preference of Koreans for white clothing for thousands of years is regarded as a distinct characteristic of Korea. The preference for white is considered as an implication of aesthetic consciousness toward cleanness, purity, humility, and deep religious belief that inspired devotion to the pure, natural, and nondecorative (Geum 1994: 58–62).

Concepts of Yin-Yang and the Five Elements, a living philosophy for Koreans since ancient times, have affected natural phenomena and human life, and created the concept of obang colors (colors of five directions) composed of five primary colors and five secondary colors. Even in the Joseon period, which limited the use of colors according to sumptuary law, the harmonious combination of these primary and secondary colors was used for children’s clothing, dancheong, and handicrafts. The use of these colors is an expression of pleasure and brilliance, and contains symbolism related to auspicious signs and warding off the evil eye (Geum 1994: 66–68).

Korean traditional color consciousness and color symbolism are reflected in costume colors for traditional rites and for representing social status or political ranks. Colors in clothing represent the national sensibility of beauty and the philosophy of life in the culture, and may be recognized as one of the cultural codes (Lee and Kim 2007: 72). In addition, the unique characteristics of colors found in costumes of each time period represent the respective aesthetic value (Geum 1994: 57), and it is possible to discuss the color consciousness and color symbolism found in Korean traditional culture based on the characteristics of color used in costume.

USAGE AND MEANING OF COLOR IN KOREAN TRADITIONAL CULTURE

Birth and Death

Rites of passage that all people celebrate between birth and death in traditional Korean culture include the 100th day after birth, the first birthday, coming-of-age celebration, wedding, the 60th birthday, and the 60th wedding anniversary. Going beyond life itself, there were funeral rites and rituals to honor ancestors. Among these, the rites of passage that Koreans still celebrate today include the first birthday, wedding, and funeral. The colors used in such rites of passage represent and are meant to express the wishes for each ceremony. For example, Koreans had a tradition of hanging a straw rope on the front door when a baby was born. If the newborn was a boy, they would attach red peppers and coals, and if a girl, they would attach green pine leaves and coals. Seeing this, would-be visitors would know not to enter the house, so as to keep the newborn and the mother safe from the risk of infectious diseases. But this tradition can also be seen as a way of chasing evil spirits away by using red and green representing Yin-Yang and the Five Elements, which signify the unity of the abundance of all living things, life, and spirit.

On one hand, there was a tradition of dressing newborns in white. In fact, newborns would be dressed in white or pale-colored clothing until they reached their 100th day. Even in the royal court of the Joseon Dynasty, which shunned the color white, they would still dress princes in white pants on their 100th-day celebration. At this time, white signified the light from the sun, and represented purity and genuineness. Therefore, dressing newborns in white shows the wish to keep evil spirits away from the baby, and the preference of Koreans for light over dark. Even in present day, the tradition remains of dressing newborns in white or pale colors.

On the other hand, white was also used to represent sadness over death. According to the theory of the Five Elements that has influenced oriental thought, the direction that represented death was north. North represented black and winter, where everything was asleep, which signified death. Therefore, black should have been used for the attire for funerals. However, white or sosaek (raw fabric color) was used for funerals in Korean traditional culture. According to the historical record, the use of white funeral clothing derived from the ancient country Bu-yeo (the second century b.c.–494) (Cho 1989: 3). Even during the times of Silla, Goryeo, and Joseon, where Buddhism or Confucianism was introduced, white was still used as funeral clothing. Thus, white was accepted as the representative color for funerals in Korean traditional culture. Funeral clothing was considered humble apparel, which did not reflect the personality of the wearer. Therefore, white was used, as a color free from embellishments or extraordinary techniques (Geum 1994: 60–61).

This Korean tradition was in contrast to Western culture, where black has been used as funeral clothing from the time of the Roman Empire, and this reached its peak during the reign of Queen Victoria in the nineteenth century (Fehrman and Fehrman 2004: 240). Western culture began to have an influence on Korea due to internationalization after the Korean War, and this also affected the funeral culture. According to the government enactment of the Simplified Family Rite Standards in 1969 and 1973, funeral clothing began to change. The standards decreed that white Hanbok (Korean traditional garments) or black suits be worn to funerals. This was the beginning of people wearing black for funerals in Korea (Yoon 2004: 33–34). In modern funerals, male mourners wear black business suits, and females tend to wear white Hanbok. However, in winter times, female mourners also tend to wear black; thus black has become the typical color for funeral clothing in modern Korean funerals.

Although white or sosaek was preferred in daily life, it was the norm to wear colorful clothing on birthdays or holidays in traditional culture. A person celebrating his or her birthday wore colorful clothing and everyone wore colorful clothing on holidays like New Year’s Day or Chuseok (Korean Thanksgiving Day). There was a tendency for younger people to wear more colorful clothing than the elderly.

The first birthday carried a special meaning of having overcome an important obstacle and babies celebrating their first birthday were dressed in colorful clothing with many auspicious designs, to wish them health and a long life. Although the clothing for boys and girls consisted of different garment pieces, the outer coats worn by children, called Obangjang Durumagi or Kachi Durumagi, emphasized the significance of color. Obangjang Durumagi used the colors red, yellow, white, blue, and green based on the Five Elements. Kachi Durumagi used saekdong, multicolored stripes, for the sleeves, as well as colors from the Five Elements for the bodice. However, black, which carried negative connotations, was not used in the outer coats. Although colorful clothing was worn primarily by little children, an adult would wear clothing with stripes similar to those worn by children to celebrate the sixtieth birthday if his or her parents were still alive.

Because adults were prohibited from wearing colorful clothing during the Joseon period due to the influence of Confucianism and sumptuary laws, Geum (1994: 79–80) interpreted this to mean that colorful garments for children reflected the yearning of adults to wear colorful clothing. The colors in those garments were also an expression of their willingness to protect children from evil spirits (see Plate 19).

Weddings and Festivals

Koreans were allowed to dress in colorful clothing of their choice for weddings and festivals. In traditional culture, festivals could include seasonal festivals or shamanistic rites performed to wish prosperity for the community. People wore bright-colored clothing in red, yellow, or blue to enhance the mood of the festival.

Weddings in traditional cultures were festive events, where families, relatives, and neighbors would get together to celebrate and bless the couple. Traditionally, in addition to blessing, weddings were regarded as the origin of humanity and morality. Therefore, the wedding ceremony was considered one of the most important rituals of a lifetime, and people would work hard to meet all respectful requirements. The bride and the groom were permitted to wear the most colorful and gorgeous clothing, usually reserved for officials. The groom wore Dallyeong (outer coat with a round neckline) worn by officials, and the bride wore Wonsam or Hwalot (ceremonial clothes) worn by the wives of the officials.

The Dallyeong would be worn by officials when entering the palace. High officials wore red, and lower officials wore blue or green according to the costume regulation. During the Joseon period, grooms were normally allowed to wear blue or green Dallyeong. The bride wore green Wonsam lined with red fabric or red Hwalot lined with blue fabric that had auspicious designs embroidered on the surface. It was a distinct feature to have contrasting colors on the inside and outside. Underneath the Wonsam or Hwalot was worn a yellow top and red skirt. Yellow represented earth, to symbolize the production of living things from earth, while red represented prosperity like fire, to invigorate their children and family (Baek 1992: 383–85) (see Plate 20).

In addition to the wedding clothes, many other goods for the wedding ceremony used certain color combinations that showed the oneness of the bride and groom. The most important color combination in Korean traditional weddings was blue and red. The meaning of this color combination can be explained in two ways: folklorically, blue and red, as they are also seen in the Korean flag, were considered the perfect colors to create the harmony of Yin-Yang (Ji 2001: 225–28). Here, red symbolized Yang, representing male, and blue symbolized Yin, representing female. Usage of these two colors for weddings was an expression of a longing to keep the harmony of Yin-Yang. However, according to the Five Elements, blue and red, which belong to the five primary colors, symbolized life, because they represented the direction of south and east, that receive energy from the sun. Therefore, people believed that this color combination would suppress and chase away the dark spirits of evil (see Plate 21).

This traditional wedding culture began to change with the modernization of society according to the introduction of Western thoughts and culture in the late nineteenth century. Changes in the philosophy and values of tradition affected the daily lives of people, and there was also a change in the groom wearing a black suit and the bride a white dress for their wedding costumes. At times, the bride transitioned to wearing a white Hanbok with a white veil (Shin and Kim 2009: 45). Traditionally colorful garments were used for festival days and white apparel was worn for daily life and funerals. Wearing a white dress instead of colorful Hanbok for the wedding ceremony can be regarded as a most specific change in wedding culture and also can be considered as a dramatic change of the Korean traditional color consciousness.

Social Structure and Status

The colors used in apparel also expressed social norm and status. Just as in ancient Europe the use of purple represented royalty and was prohibited for wear for others by sumptuary law (Charlene 2008: 175–87), traditional Korean society also kept the social order by designating colors that displayed social status. Colors that expressed social status were evident in the political realm. In particular, different colors were used to show the political hierarchy from the king to the officials. Red was used for kings and different nuances of red were used for high officials. Lower-status officials wore blue or green. Color restrictions were also used to express the level of status for the ladies of court. In terms of Wonsam, the empress wore yellow, the queen wore red, and the princess wore purplish red. The wives of officials wore green Wonsam. Farmers or commoners were prohibited from wearing colorful apparel in daily life. Exceptions to this rule included shamans, gisaeng (female entertainers), and children, who were allowed to dress colorfully despite their social status. However, all people were allowed to wear colorful clothing for special ceremonies, including weddings, birthdays, and holidays.

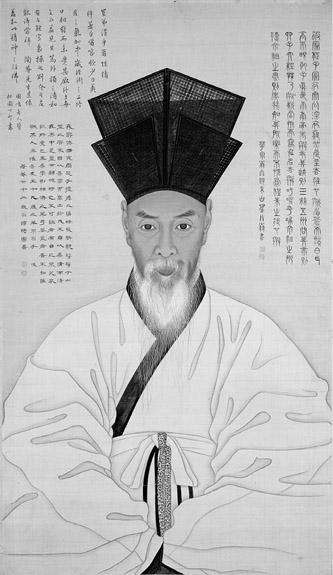

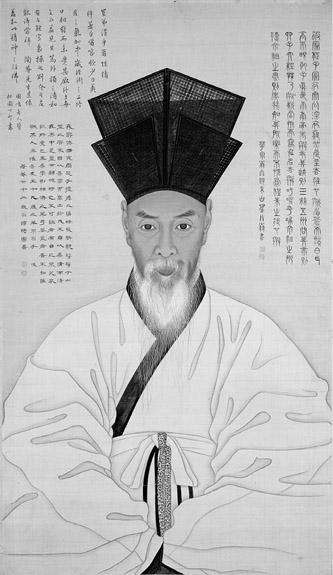

Figure 10.1 Portrait of Confucian scholar Chae Lee, wearing Simui, 1807. The Simui, which Confucian scholars wore daily, emphasizes the harmony of black and white and is symbolic of Confucianism asceticism and the honorable character of the nobility.

Source: The National Museum of Korea.

Specific colors were designated for people in academia or religious orders, which were thought to express their character. For example, scholars who observed Confucianism during the Joseon period wore Simui, a white outer coat with black border trimming, to visually express the asceticism of Confucianism. White, in this case, represented purity and innocence, and the harmony of black and white created a calm and serene atmosphere, expressing their intelligent and noble spirit. See Figure 10.1. Such colors also reflected the symbolism of cranes, which were not caught up in secular desires but glided in the skies with honor and unyielding spirit (Geum 1994: 63–64).

SIGNIFICANCE AND INTERPRETATION OF COLORS IN CONTEMPORARY KOREAN SOCIETY

According to the Color Experience Pyramid of Mahnke (1996: 11–18), responses to color can be influenced by trends, fashion, styles, and personal relationships. This means that the color consciousness or preference in Korean traditional culture can also be changed by sociocultural changes in modern society. Traditional color and its meaning have been inherited or acculturated in contemporary Korean society and are analyzed through the following representative cases.

Expression of Identity

The use of colors for the traditional purpose of depicting social status or identity still takes place in modern society in various ways, and these include identifying and expressing company, brand, college, occupation, and gender.

Colors to symbolize gender can be found in the color of baby’s clothing such as pink and light blue. Even though there are those who criticize the practice of stereotyping babies with colors, usually girls are dressed in pink and boys are dressed in light blue in Korea. Another case where colors symbolize gender can be found in the color of Hanbok worn by mothers of the bride and the groom at weddings. Although this practice has been weakening since 2000, with a greater emphasis being placed on personal preference and fashion trends, the groom’s mother is expected to wear blue Hanbok, and the bride’s mother to wear pink Hanbok. This phenomenon stems from the wearing of blue and red apparel during traditional weddings in accordance with the harmony of Yin and Yang. However, as this phenomenon began from the latter half of the twentieth century when Western-style weddings became more established as a social practice, it is still not easy to ignore pink or red to symbolize females and blue to symbolize males.

The use of varying colors to visually differentiate academic majors with different colored hoods of graduation gowns can also be considered as identifying colors. Since the Western education system was introduced to Korea in the early twentieth century, many universities uniformly used black as a main color for the gown, with hoods in various colors according to the academic major. The colors include orange for engineering majors, light blue for education majors, and white for liberal arts, and so on. However, in recent years, certain universities have replaced black with the color that represents the university (e.g., blue for Yonsei University and red for Korea University). This is viewed as an attempt by the universities to emphasize their own identity through the use of color.

The judiciary in Korea have long worn black gowns, following the Western style. As black is appropriate for the expression of dignity and power, it was chosen as the main color for the new judiciary costume in 1998. However, purplish red satin jacquard front panels were added for the new design to emphasize Korean traditional beauty and present a dignified image. Indeed, red was used for high officials in the Joseon period, so the color combination of black and purplish red could explain the continuation of Korean traditions as well as authority in administering justice.

Expression of Ideology

The symbolic meaning of color can easily be observed in contemporary Korean political culture. It was difficult to express one’s own political ideology in a centralized government under the monarchy of Korean traditional society. However, in modern society, there emerged parties with different thoughts and ideologies. Each political party or candidate chose a certain color to appeal to the voters by imprinting their political idea through color.

Generally, right-wing parties or politicians who support stability and conservatism prefer to use blue, while left-wing parties who support power and liberalism prefer to use red. However, due to Korea’s unique political background, it should be noted that the use of red in politics may remind people of communism and result in negative feelings of voters. At the end of the twentieth century, the colors often seen in Korean politics were blue and green, which symbolized stability, honesty, harmony, and growth (Cheon and Kim 2002: 25–31). President Myung-Bak Lee also strategically used blue to present an image of stability or equilibrium, practical conservatism, with an emphasis on economic growth.

However, the most successful use of colors for modern politicians in Korea was the use of vivid yellow by the former presidents Dae-Jung Kim and Moo-Hyun Roh. Yellow had already been used by former president Dae-Jung Kim when he ran for president in 1987, to minimize his strong image as a democratic activist, as well as the negative image of his progressive tendencies. He also wanted to emphasize the hope and peace of democracy through the color yellow. The color yellow had been used by former president Corazon Conjuanco Aquino of the Philippines and was an effective reminder of the Filipino democracy (Cheon and Kim 2002: 28).

Since the year 2000, yellow has become a trendy color symbolizing the hope of a new millennium. Some companies with low-price strategies, such as E-mart and S-Oil, used yellow color for their corporate identity. Although yellow, according to the theory of the Five Elements, represents centrality or the honor of an emperor, the former president Moo-Hyun Roh chose this color in the 2002 election as a strategy to represent a government that was open to the public. Those who supported Roh used yellow scarves, balloons, and flags during rallies. In the 2005 Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) Summit, President Roh also tried to emphasize his political idea visually in choosing yellow for his traditional outer coat, Durumagi; See Figure 10.2.

Some politicians have experienced negative results because of a poor choice of colors. In 2006, a female candidate (Keum-Sil Kang) for mayor of Seoul chose violet as her campaign color to symbolize a new and changing political environment, breaking the contrasting ideological borderline of red and blue. However, unlike red or blue, violet lacks visual clarity and strength. In addition, based on the preference and symbolism of the color violet in Korea, it was not suitable for politics. Violet, a tepid color that is neither red nor blue, is not popular even for children’s or women’s apparel in Korea, unlike the United States or Europe. Furthermore, former first lady Hee-Ho Lee wore a violetHanbok to represent the color of the national flower, Rose of Sharon, as a symbol of silent political resistance and patriotism when Dae-Jung Kim was under house arrest because of his pro-democracy movement. For the families who fought for democracy in Korea, violet is a color that reminds them of pain and suffering. Therefore, the violet campaign of Kang, which overlooked those various meanings of violet in Korean culture, was regarded as an inappropriate strategy.

Figure 10.2 Leaders in Durumagi for the official photograph of the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) Summit, Korea, November 19, 2005. President Moo-Hyun Roh (first row, center) was wearing yellow Durumagi to express his political ideology of being open to the public.

Source: Ministry of Culture, Sports and Tourism of the Republic of Korea.

The Vitality of Festivals

Colors represent the emotions of those who use them and therefore often represent a special event. As the essence of a festival is to boost one’s consciousness to the highest level of joy, the sophisticated and elegant colors of the upper class were rejected, and instead bright colors such as red were used to represent freedom, passion, and excitement (Kwon 2005: 13–14). The primary colors used in Korean traditional culture heightened the atmosphere of festivals and added vitality to the event. The uniforms of participants of sports events that feature bright colors with strong contrasts or complementary color combinations also visually enhance the active movement of the participants and imbue the event with vitality.

A new perception of the color red resulted from the 2002 Korea-Japan World Cup. At the time, Koreans cheered for their team with red T-shirts with the inscription, “Be the Reds.” This shocked the world with their passionate street cheering that figuratively and literally painted the streets red. A record number of 7 million supporters came out to the plaza and streets to cheer during Korea’s quarterfinals with Germany. With sales of 25 million shirts, which is one shirt for every two Koreans, it is not an overstatement to say that at the time this served as the national shirt for Koreans. The Koreans at the stadium, plaza, and streets cheered “Be the Reds” to emphasize their oneness, and they prayed that their cheers and the red energy would reach the players on the field. This event served as an opportunity for the negative concept of red to change to positive and represent optimism.

In Korean traditional culture, red represented honor and respect, and was highly preferred with its symbolism for life, creation, and wishing for health and peace. However, at the end of the nineteenth century, with the modernization of Korea as the turning point, red began to carry a different symbolism in connection with social factors. The political environment of the twentieth century made red symbolic of rapid revolution and social upheaval, and came to represent the political ideology of communism. For Koreans who lived through the Korean War, red came to mean communism, socialism, and radical progressivism. In other words, in the twentieth century, Korean society ignored the beauty of the color itself, perceiving red as part of communist ideology. There were instances where red was prohibited or avoided, leading to the phrase red complex (Kwon and Kim 2005: 22–29).

The survey done by Nam and Choi (2007: 30–34) on free association and preference for the color red is a good reflection of this. Survey respondents in their sixties, who had experienced the Korean War, tended to associate red with communism and communist ideologies; respondents in their forties who had lived through the social movement toward democracy associated the color red with strikes and labor-management disputes. Only 12 percent of respondents said they liked the color red. However, 88 percent of respondents in their twenties responded that they liked the color red, as their primary association was with the FIFA World Cup.

Figure 10.3 Supporters gather in Seoul Square to cheer for Korea in its game against Argentina during the South Africa World Cup, June 17, 2010. Since the 2002 Korea-Japan World Cup, the color red for Korean society has come to represent a wish for victory, the joy and passion of festivals, and freedom and public ownership. Photograph by Jae-Gone Kim.

The 2002 Korea-Japan FIFA World Cup gave Koreans a new perception of the color red as symbolizing vitality and festival. In particular, unlike the negative perceptions of the past, now red is thought to draw out passion and excitement in Koreans, and to be a color symbolizing freedom and public ownership, joy, passion, and wishing for victory that connects Koreans in oneness. See Figure 10.3.

Interrelationship with International Trends

In modern global society, world fashion trends can be quickly and easily grasped thanks to technological advancements, and there is a parallel trend for colors. A characteristic of the Korean fashion market is quick acceptance of international trends and changes. Grayish or dull colors like beige, taupe, brown, or khaki, traditionally thought to be unclean, were widely accepted after trench coats became popular through Western movies and magazines following the Korean War. In addition, black, which represents modernism, is actively used and preferred in Korean society as a result of the influence of Western culture.

Saito (1996: 1–10), who studied color preferences of modern Korea and Japan, discovered that Koreans showed a higher preference for white and black compared to the Japanese. She explained that Koreans’ preference for white stems from traditional culture, but did not give a detailed explanation for the high preference for black. However, Lee and Kim (2007: 71–79), who studied women’s apparel color from the Joseon Dynasty to the end of twentieth century, explained that the reason for the popularity of black in Korean fashion is the influence of the international fashion trend. In the early twentieth century, black was used for school uniforms and was centrally used for trendy apparel worn by women who studied abroad or had no bias toward accepting Western culture. Therefore, black was accepted as the color that represented Westernization and modernism.

Black was also popular in Western society since industrialization, and is still preferred as a basic and trendy color. Although black is not perceived as an optimistic color by itself, it displays a noble, elegant, and avant-garde image when it is used for fashion or products. However, the preference of Koreans for black nowadays is rather unique. Besides wearing black as their daily apparel, Koreans tend to dress in black suits to attend weddings as well as funerals. And also many entertainers choose black dress over any other colors for awards ceremonies. It seems that Koreans, who were once called the “white-clad folk” because of their preference for white, have been taken over by black due to the influence of Western culture. High preference for black in contemporary Korean culture is not only because it is a basic color considered compatible with any other color, but also because it is related to the international symbolism of black as expressing high quality and sophistication.

Promotion and Marketing Strategy

Traditional usages and symbolism of colors are still found in contemporary Korean society in diverse and purposeful ways. Furthermore, colors are used for the purpose of promotion and marketing strategies. Using colors to express one’s identity or political ideology also falls into this category. In particular, many businesses use a color-based marketing strategy to boost sales and profits by using colors that touch the consumers’ psychology and emotions. For example, during the 2002 Korea-Japan World Cup, the explosive popularity of red was reflected in fashion items and marketing. Inspired by the red passion of Korea, Chanel’s make-up creator Dominique Moncoutois created a red lipstick from the red of the Korean flag naming it “Rouge de Seoul,” and releasing it to the Korean market. This was the first time a city was used as the name of a Chanel product. Later it was included formally as one of the regular items of Chanel (Jeong 2003: 306–7).

In addition, a credit card company of Korea, Hyundai Card, in 2006, introduced three types of premium-level credit cards in order to display a luxurious image and to strategically differentiate the service level using the three colors of red, purple, and black. These three are representative colors for Koreans for luxury and high quality. However, the fact that the company placed black at a much higher level than red and purple with the marketing strategy of using black for the top 0.05 percent VVIPs is a good example of the popularity of black and its meaning among Koreans for promotion and marketing strategy.

Thus characteristics of Korean traditional color symbolism, which may contain different meanings according to an event’s purpose and aspiration, became more complex with the multiple symbolisms introduced by Western cultures. When using color for promotion and marketing strategy, it is important to understand both traditional and current symbolism of the chosen color and to use it to effectively elicit consumers’ latent desires.

CONCLUSION

Understanding how colors have been used in Korean society from the past to the present explains characteristics of Korean culture, and provides opportunities to understand a Korean aesthetic consciousness, way of thinking, and mode of living. The use of colors in Korean culture can be summarized as having two main characteristics.

First, an important characteristic of color in Korean society is the coexistence of change over time, together with the continuance of tradition to the present. That Koreans, who preferred white to the extent that they were called “white-clad folk,” began to adopt black clothing in the twentieth century is the result of the pursuit of Westernization and the acceptance of international fashion trends. Yellow, once regarded as the center of all things and the color of the empire, has shifted to a populist image because Koreans have followed the flow of political and social change. The restrictive functions of color in the past due to reactionary conservatism and fulfilling the functions of symbolizing status and rank have shifted to various functions such as individual preferences, flow of fashion trends, and marketing strategies. It can be said that changes in preferences, symbolism, functions, and roles are derived from the diversification and fractionation of the available color range through the development of technology for creating colors, and are the inevitable consequence of information exchange resulting from globalization.

The fact that white is still preferred by people, clear and bright colors are favored, and the function of color used to designate status, class, or rank in the past finds its equivalent today in designating affiliation and occupational identity shows that the traditional characteristics of color are still sustained today. From this, it can be interpreted that traditional viewpoints of color or color consciousness influence contemporary Koreans, consciously or unconsciously. This implies the existence of a Korean prototype of color that has germinated through 5,000 years of history.

Second, color in Korean culture is characterized by the strong action of meaning-centered color consciousness. Traditionally, Koreans tended to give symbolic meanings to colors, and consider the color combination harmonious to the extent that the symbolic meanings were harmonious with each other. As each color had different meanings, Koreans wanted to express what they desired in colors by highlighting one meaning that was suitable to a specific event or situation. Those Korean ancestors who preferred the color white in daily life as well as in relation to birth and death may be considered as positively accepting each of the different meanings given by white. That they gave different symbolic meanings to clothes by the use of obang colors according to the Five Elements also shows the meaning-centered color consciousness. Despite the discord with tradition, the fact that Koreans diversified color meanings according to objectives and functions, gave meanings and symbols to each color to express political identity and ideology, and used colors in promotion and marketing strategies may also be regarded as the strong expression of a meaning-centered color consciousness traditionally handed down.

What is unfortunate in the use of colors today is that traditional meanings or symbols of color, sometimes diluted or distorted due to thoughtless acceptance of foreign cultures, or by giving or interpreting meanings of foreign cultures just for convenience, result in weakening traditional spirits. This study suggests that it is not only necessary to accept the global trend in modern society, but also to respect traditional characteristics to hand down, develop, and modernize the traditional culture in an appropriate direction. In other words, understanding how the traditional prototype of color germinated from long-standing history and culture, as well as accepting a global color prototype and international color trend, will bring a higher likelihood of developing creative and marketable design, and lead to the necessary attitude not only for those who belong to the culture, but also for others who want to communicate with that culture.

REFERENCES

Baek, Y. J. (1992), Korean Costume, Seoul: Gyeungchunsa.

Charlene, E. (2008), “Purple Pasts: Color Codification in the Ancient World,” Law and Social Inquiry, 33/1: 173–94.

Cheon, J. I., and Kim, I. C. (2002), “A Study on the Color Strategy of Presidential Elections in Korea,” Journal of Korean Society of Color Studies, 16/2-3: 25–34.

Cho, W. H. (1989), “A Study on Mourning Dresses in Joseon Dynasty,” PhD diss., Sookmyung Women’s University, Seoul.

Eum, J. S., and Chae, K. S. (2006), “Comparison Study on Perceived Meaning of Color and Clothing Color of Korea and Japan,” Journal of the Korean Society of Costume, 56/6: 16–32.

Fehrman, K. R., and Fehrman, C. (2004), Color: The Secret Influence, 2nd ed., Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson/Prentice Hall.

Geum, K. S. (1994), The Beauty of Korean Traditional Costume, Seoul: Youlhwadang.

Jeong, S. H. (2001), “Color Consciousness of Koreans,” in Korean Society of Color Studies (eds.), The World of Various Colors, Seoul: Kukje Books, 170–76.

Jeong, Y. H. (2003), “Chanel, Rouge de Seoul, Presentation Ceremony, Enthusiastic Shout Contained on the Lipstick,” Happy House, 185: 306–7, Seoul: Design House.

Ji, S. H. (2001), “Korean Architecture Seen in Color,” in Korean Society of Color Studies (eds.), Now, Colors Tell, Seoul: Kukje Books, 221–28.

Kim, Y. S. (1987), Royal Costume in the End of JoseonDynasty, Seoul: National Culture Library Publishing Association.

Kwon, Y. G. (2005), “Colors for Festivals and Festivals of Color,” Proceedings of the Korean Society of Color Studies 2005 Summer Symposium, 7–14.

Kwon, Y. G., and Kim, N. R. (2005), “A Study on the Signification and Symbol of Red in Korea, China and Japan,” Journal of Korean Society of Color Studies, 19/2: 21–36.

Lee, J. H., and Kim, Y. I. (2007), “Analysis of Color Symbology from the Perspective of Cultural Semiotics Focused on Korean Costume Colors According to the Cultural Changes,” Color Research and Application, 32/1: 71–79.

Lee, S. H. (2009), “A Study on the Color Consciousness and Symbol in Sillain in SamGookYousa,” Journal of Korean Society of Color Studies, 23/1: 157–72.

Mahnke, F. H. (1996), Color, Environment, and Human Response: An Interdisciplinary Understanding of Color and Its Use as a Beneficial Element in the Design of the Architectural Environment, New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold.

McCool, M. (2008), “Can Color Transcend Culture?,” Proceedings of Professional Communication Conference, 206–13.

Nam, J., and Choi, B. J. (2007), “The Change of Red Color Symbolism by Generation in Korean Culture,” Journal of Design and Art, 8: 17–34.

Park, H. I. (2004), “The Color Consciousness Which Appears in Korean Culture (3): From Antiquity Age to Modern Time,” Journal of the Korean Society for Philosophy East-West, 33: 313–33.

Saito, M. (1996), “A Cross-Cultural Survey on Color Preference in Asia Countries (1): Comparison between Japanese and Korean Emphasis on Preference for White,” Journal of the Color Science Association of Japan, 16/1: 1–10.

Seo, B. H. (2009), “The Effect of Three Religions on the Unexpressed Color of Traditional Korean Costumes,” Journal of Korean Society of Color Studies, 23/1: 131–44.

Shin, H. S., and Kim, J. Y. (2009), “A Study on Wedding Costume Worn during the Reigns of King Gojong and Sunjong,” Journal of Seoul Studies, 35: 10–58.

Turner, V. W. (1975), Dramas, Fields, and Metaphors: Symbolic Action in Human Society, New York: Cornell University Press.

Yoon, E. Y. (2004), “A Study on Mourning Garments in Recent Funeral Rites: Centering around Gwangju,” master’s thesis, Choongnam National University, Daejeon.

Zollinger, H. (1999), Color: A Multidisciplinary Approach, Zurich: VHCS; Weinheim: Wiley-VCH.