26. Vision Quest

Map G (p. 139)

| Duration | half day |

| Distance | 5 km |

| Level of Difficulty | steady, steep climb |

| Maximum Elevation | 2165 m |

| Elevation Gain | 765 m |

| Map | 83 C/1 Whiterabbit Creek |

Access: Park your vehicle at the waste transfer site 2 km north of the David Thompson Resort, or 42 km south of Nordegg, or 41 km north of the Banff National Park boundary.

0.0 kmtrailhead

0.6 kmvision quest site

2.0 kmridge

2.5 kmcliff face

5.0 kmtrailhead

This short, but very steep, climb up an open spine takes you through an old First Nation vision quest site en route to the top of a ridge overlooking Abraham Lake.

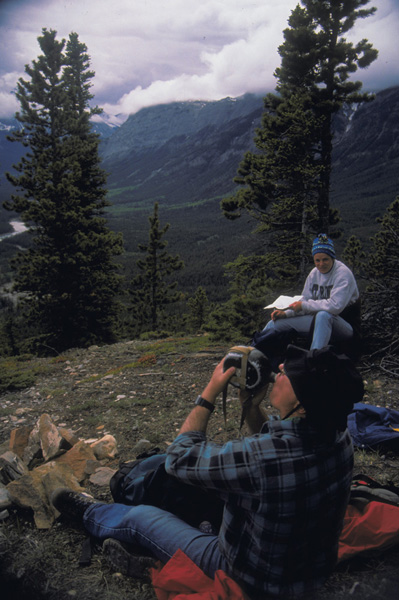

Walking along the top of Vision Quest ridge, you can enjoy a panoramic view of Abraham Lake. Courtesy of Chris Hanstock

A fence encloses the waste transfer site to discourage bears from scavenging. You can either scramble up the slope beside the fence or find a path 25 m down the road. It heads toward the fence, where the path makes a 90-degree turn, snugging the fenceline to its end. The trail now begins its climb through open lodgepole pine forest. Once through the pines, you find yourself at the bottom of a long and steep, but open, slope. The route is obvious. This south-facing slope is as dry as it is open, but in spring dainty butter-and-eggs and pussyfoots sprinkle the hillside. If there was any doubt in your mind at the beginning of this hike about the steepness of the climb, the first 100 m should dispel any questions you may have had. The huffing and puffing are worth it, though, as you work your way up. As you rise above the pine trees, the view continues to improve. Looking to the north you can see Windy Point and looking south you can see as far as the Kootenay Plains.

Historical Footnotes: Triangle Peak

Triangle Peak is a mountain described and climbed by University of Toronto geologist A.P. Coleman. It is Vision Quest ridge and it describes the profile of the ridge when viewed from below from the banks of the North Saskatchewan. On July 18, 1892, Coleman forded the Cline River near its confluence with the North Saskatchewan River, camped and then climbed the ridge and described the following scene: “A beautiful small lake [Whitegoat Lake] and white salt licks broke the surface of prairie below us, and looking down on our specks of ponies, we could imagine the brown herds of buffalo drinking at the pond or streaming toward the salt lick, where the hunters lay in wait for them. One could still see their hollow paths and wallows and an occasional whitened skull in 1892.”

Suddenly, as you approach a copse of pines in a notch, the ridge flattens. Here the trees are festooned with metres of cloth that once were brightly coloured but are now faded. This may be a vision quest site of at least one First Nations person seeking direction in his or her life. A perfect site to find peace and happiness, the notch invites a stop to enjoy the view before walking on through the knot of pines.

The slope becomes steeper and steeper. Finally, it flattens near the top. Once at the top, continue along the ridge. As you approach the cliff face in front of you, the ridge that you are climbing becomes quite narrow and is not for the faint of heart. There is, though, a glorious view of the North Saskatchewan River valley, dominated by the aquamarine waters of Abraham Lake. To the right is the Whitegoat Creek valley, while below on your left is BATUS Creek.

Return the way you came.

Historical Footnotes: The Vision Quest

“[T]he Rocky Mountains are precious and sacred to us. We know every trail and mountain pass in this area. We had special ceremonial and religious areas in the mountains.…These mountains are our temples, our sanctuaries, and our resting places. They are a place of hope, a place of vision, a place of refuge, a very special and holy place where the Great Spirit speaks with us.”

When Chief John Snow of the Stoney Bighorn Reserve wrote his book These Mountains Are Our Sacred Places in 1977, it was at a time when much of what the Stoneys held dear was threatened by the tides of change in the North Saskatchewan River valley. The Bighorn Dam was completed and had flooded much of the historic hunting grounds of the Stoneys, and plans for upscale resorts in the valley had been presented to the provincial government. Much of the Stoney world at Bighorn had changed forever.

It was, perhaps, against this backdrop of local turmoil and of a growing awareness on the part of First Nations across North America that Native spirituality underwent a renaissance. In Chief John Snow’s sacred mountains, that renaissance took the form of sun-dances, sweats and vision quests. A vision quest is a solitary experience by one person, almost always a male, who seeks wisdom and guidance by isolating himself from his community. Prior to embarking on his mission, he participates in a sweat lodge ceremony in which he and the others present are purified both physically and spiritually through fasting and praying. The sacred pipe is smoked to Waka Taga, the Great Spirit. It is first offered to the person sitting on the east side of the sweat lodge, then, moving in a circular fashion, to the person on the north side, then the west side and finally ending with the leader of the ceremony holding the stem of the pipe toward the north.

Taking a short break at the vision quest site.

After this ceremony, the seeker sets off on his vision quest. Finding a secluded spot, he remains there for a number of days, fasting and praying for guidance for his future. His vision often takes the form of communication between himself and a spirit, which can take the form of an animal, bird or even an inanimate object like a rock. He may even acquire that form as his guardian spirit. Carrying an object belonging to his guardian spirit, such as bones or feathers, then, protects him in times of trial.

Once he has received instructions from his spirit, he returns to his community, where his experiences will be interpreted for him.