U.S. COPYRIGHT AND INTERLIBRARY LOAN PRACTICE

Cindy Kristof

Interlibrary loan (ILL) practitioners, like others working in libraries, react to the topic of copyright in a variety of ways. Some see a mild nuisance, some a menacing specter; most see something in between. However, at least for ILL, copyright does not need to be viewed with fear. Practice in this area of librarianship is largely well established, supported by both law and agreed-upon guidelines. As Lee Andrew Hilyer writes, “An extensive knowledge of every nuance of copyright law is not required for successful (and legal) operation of an ILL department.”1

The original purpose of copyright law, as established in 1788 by the ratified United States Constitution, was “to promote the Progress of Science and useful Arts by securing for limited Times to Authors and Inventors the exclusive Right to their respective Writings and Discoveries.” This protection was meant to encourage scientific progress, innovation, and invention. The purpose of ILL as defined by the Interlibrary Loan Code for the United States is “to obtain, upon request of a library user, material not available in the user’s local library.”2 ILL does not exist to contravene copyright or to undercut commercial publishers’ profits; rather, ILL and copyright law are meant to work together harmoniously, in order for libraries to provide the widest possible access to copyrighted works by their patrons. This access naturally benefits society as a whole.

LAWS AND GUIDELINES

In the United States, copyright law is federal law and is contained in Title 17 of the United States Code. Although detailed knowledge of copyright law is unnecessary, it does help ILL practitioners to have a basic foundation on which an understanding of the applicable laws and guidelines can be built. Outlined in the following paragraphs are Sections 106 through 109, the most relevant to ILL practice.

Section 106—Exclusive Rights of Copyright Owners

As part of the 1976 Copyright Act, the copyright owner—not necessarily the author or creator—is granted the following six exclusive rights in copyrighted works:

- to reproduce the copyrighted work in copies or phonorecord

- to prepare derivative works based upon the copyrighted work

- to distribute copies or phonorecords of the copyrighted work to the public by sale or other transfer of ownership, or by rental, lease, or lending

- in the case of literary, musical, dramatic, and choreographic works, pantomimes, and motion pictures and other audiovisual works, to perform the copyrighted work publicly

- in the case of literary, musical, dramatic, and choreographic works, pantomimes, and pictorial, graphic, or sculptural works, including the individual images of a motion picture or other audiovisual work, to display the copyrighted work publicly

- in the case of sound recordings, to perform the copyrighted work publicly by means of a digital audio transmission

Note that the reproduction and distribution of copies of a work are exclusive rights; however, reproduction and distribution are precisely what ILL departments need to do. Therefore, there are exceptions to Section 106 in the law. These exceptions are specified in Sections 107, 108, and 109. They are paraphrased and summarized in the following paragraphs, out of sequence for purposes of clarity. Abridged text of Sections 106–109 may be found in appendix 4.1.

Section 109—First Sale

Section 109 is the most straightforward as it applies to ILL practice. It contains a vital limitation on exclusive rights—the “effect of transfer of particular copy or phonorecord”—and what is commonly referred to as the “First Sale Doctrine.” This principle allows people to give books, CDs, and DVDs as gifts. It also allows libraries to purchase and lend copyrighted works. It allows individuals and institutions to hold book sales. The owner of the copyrighted work is free to give it away or to loan, resell, discard, mutilate, or destroy it. A vital and frequently misunderstood distinction is that the ownership applies to the work as a physical item, not the intellectual content contained within it. Section 109 does not apply to works licensed by contract (see the section “ILL of Licensed Electronic Journals” later in this chapter).

Section 108—Reproduction by Libraries and Archives

Section 108 contains “limitations on exclusive rights: reproduction by libraries and archives.” Within limitations, this part of the law allows ILL departments to make, send, and receive copies of works. These copies can be for individual patrons, for other libraries, or for preservation, providing they conform to certain conditions. These rights can even apply to copies of an entire work or to substantial portions, if it has been determined, after a “reasonable investigation,” that a copy cannot be obtained at a fair price or if the copyright holder has alerted the Register of Copyrights that the work is no longer being marketed.3 Other conditions include the following:

- 1. To use Section 108, libraries must be eligible. Eligible libraries are those whose collections are open to the public, available not just to affiliated researchers but also to outside researchers.

- 2. Reproductions and their distribution must be on a cost-recovery basis only, not for direct or indirect commercial gain.

- 3. For a library user, the library or archive can copy one article from a periodical issue or a portion of another type of copyrighted work, such as a book chapter.

- 4. The copied work must include the copyright notice that appears on the work, or if that is absent or cannot be located, a notice must be included stating that the work may be protected by copyright.

- 5. The copy must become the property of the user.

- 6. The library or archives must have no notice that the copy would be used for any purpose other than private study, scholarship, or research.

- 7. The library or archives must display prominently, at the place where orders are accepted, and include on its order form, the following prescribed warning of copyright:

NOTICE

WARNING CONCERNING COPYRIGHT RESTRICTIONS

The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted material.

Under certain conditions specified in the law, libraries and archives are authorized to furnish a photocopy or other reproduction. One of these specific conditions is that the photocopy or reproduction is not to be “used for any purpose other than private study, scholarship, or research.” If a user makes a request for, or later uses, a photocopy or reproduction for purposes in excess of “fair use,” that user may be liable for copyright infringement.

This institution reserves the right to refuse to accept a copying order if, in its judgment, fulfillment of the order would involve violation of copyright law.

- 8. The copying must not be systematic; thus, this part of the law extends to copying and distribution of a single copy of the same material on separate occasions, but does not apply to related copying or distribution of multiple copies of the same material, whether made on one occasion or over a period of time.

- 9. Interlibrary loan arrangements such as consortial reciprocal agreements must not make copies in such “aggregate quantities” as to “substitute for a subscription to or purchase of” copyrighted works—Section 108(g)(2).

- 10. The rights of reproduction and distribution under this section do not apply to musical works (e.g., sheet music or recording of a musical performance), a pictorial, graphic or sculptural work, or a motion picture or other audiovisual work other than an audiovisual work dealing with news. Works published as adjuncts to articles or chapters such as illustrations, diagrams, charts, tables, photographs, and the like are the exception to this rule; they may be copied along with the rest of the work.

CONTU Guidelines

CONTU

Because the law itself is vague, Congress established the National Commission on New Technological Uses of Copyright Works, also known as CONTU, to develop more specific guidelines and to help define the “aggregate quantities” that could potentially “substitute for a subscription to or purchase of” copyrighted works. CONTU operated during the development and passage of the Copyright Act of 1976, between 1975 and 1978, and on July 31, 1978, it issued its Final Report. Chaired by Stanley H. Fuld (1903–2003), who served as Chief Judge of the New York Court of Appeals from 1967 through 1973, this diverse group had expertise in law, librarianship, education, and publishing.4 Chapter 4 of the CONTU report, “Machine Reproduction—Photocopying,” outlines the recommended interpretation of the law used in ILL practice today.5 At that time, photocopiers were the newest technology. For copies reproduced in digital format, as is commonplace today, digital copies must not be distributed outside the library or made available to the public outside the premises of the library.6 (See “Electronic Delivery” later in this chapter.)

The “Suggestion of Five”

The CONTU Final Report asserts that six or more copies of a recently published work could substitute for a subscription. “Recently published” is defined by CONTU as “within five years prior to the date of the [ILL] request.” Thus, five copies from any single journal title requested within five years of the publication date of the work are considered to be within the so-called Suggestion of Five, also known as the Rule of Five or the 5/5 Rule. Copying of articles published more than five years after the date of the ILL request does not fall under Section 108, but may fall under Section 107.

For a very concrete example of the Suggestion of Five, over the course of the calendar year 2007, a library could have borrowed for any of its patrons the following five articles, just once each, appearing within the past five years of publication of the Journal of Academic Librarianship, while remaining within the Suggestion of Five:

- 1. Volume 32, Issue 3, May 2006, pages 251–58

- 2. Volume 30, Issue 2, March 2004, pages 132–35

- 3. Volume 33, Issue 4, July 2007, pages 462–77

- 4. Volume 31, Issue 1, January 2005, pages 46–53

- 5. Volume 32, Issue 1, January 2006, pages 69–78

However, once a sixth article is borrowed and filled (e.g., Volume 31, Issue 4, July 2005, pages 317–23), this action is defined by CONTU as potentially beginning to substitute for a subscription. To request that sixth article, the borrowing library must seek another source. Alternatives may include, but are not limited to, the following:

- 1. Borrow the sixth article from another library, and pay a copyright fee to the publisher, through the Copyright Clearance Center (discussed later in this chapter).

- 2. Deny or refuse the ILL order to its patron because the title is “closed” for the rest of the calendar year, suggesting the user place the request at the beginning of the next calendar year if still needed.

- 3. Start a subscription to the journal.

- 4. Purchase the article from a commercial document delivery vendor.

- 5. Purchase the article directly from the publisher on behalf of the patron.

- 6. Refer patrons to a nearby library with the title in its holdings.

The designation of “calendar year” can be confusing. The following example helps illustrate this concept. If a library receives an ILL borrowing request in September 2007 for an article published in the July–August 2002 issue of the Journal of Academic Librarianship, the publication date falls just outside the five years preceding the ILL request date; therefore, this request would fall outside the Suggestion of Five. Nevertheless, many libraries choose simply to include the remainder of the calendar year in their calculations.

When placing an ILL request for a photocopy, the borrowing library must indicate whether it complies with CONTU guidelines. This notification is commonly done with the abbreviations CCG or CCL. CCG is used for articles borrowed under the Suggestion of Five and means the request “complies with copyright guidelines,” in reference to the CONTU guidelines. CCL means the request “complies with other provisions of the copyright law” (i.e., Section 107). Many libraries use CCL to indicate requests ordered from commercial document delivery vendors that include royalties in their fees.7

Under CONTU, it is the responsibility of the borrowing library to maintain records of ILL requests, both filled and unfilled, that could fall under the Suggestion of Five. These records must be retained for three years. Specifically, CONTU requires the borrowing library to maintain these records “until the end of the third complete calendar year after the end of the calendar year in which the respective request shall have been made.”8 In other words, ILL requests dated and filled between January 2003 and December 2003 may be discarded after December 2006. Electronic records are perfectly acceptable.

Although guidelines, including the CONTU guidelines, are not law, they are well established, and most ILL practitioners use them as an upper limit. However, a use beyond the CONTU Suggestion of Five might indeed pass the four-factor test and fall on the side of fair use. This decision must be made carefully on a case-by-case basis and according to local policy (see “Section 107—Fair Use” later in this chapter).

Borrower Responsibilities and Options

The decision by a library about whether to subscribe to a journal is out of the scope of this chapter. However, acquisitions staff and ILL practitioners should work closely with one another to ensure that royalty fees, as well as the more hidden ILL transaction costs, do not exceed the price of a subscription and to ensure that collections are managed so that patrons’ needs are met. Once a subscription to a journal title is started, the library can begin to borrow recent articles freely from it.

The Copyright Clearance Center (CCC; www.copyright.com) opened for business in 1978. It was organized by authors, publishers, and content users in response to a suggestion of Congress preceding the Copyright Act of 1976. Most publishers enable easy royalty payments for ILL transactions through CCC. Although their rationale is not known, some publishers do not participate in CCC. Frequently, commercial document delivery vendors, who pay publishers’ royalties to provide articles, have arrangements with non-CCC publishers. Additionally, it has become much easier to purchase articles from publishers as publishers have begun to make individual articles available for immediate electronic download. It is hoped that outright denials of ILL requests are relatively rare due to alternate means of obtaining published works.

The CCL designation should be used for materials that are on order but not yet received by the library as well as for items currently unavailable, such as those at the bindery or in transit to off-site storage locations. However, what about articles from electronic journals that are currently embargoed? These requests should fall under the Suggestion of Five, and CCG should be used. Appropriate royalties should be paid as with any journal without a current subscription, as these items are neither currently owned nor yet paid for.9

Section 107—Fair Use

Section 107 describes the popular concept of fair use. Fair use is a defense that can be used in court against allegations of copyright infringement. Courts consider the following four factors:

- 1. The purpose and character of the use, including whether such use is of a commercial nature or is for nonprofit educational purposes

- 2. The nature of the copyrighted work

- 3. The amount and substantiality of the portion used in relation to the copyrighted work as a whole

- 4. The effect of the use upon the potential market for or value of the copyrighted work

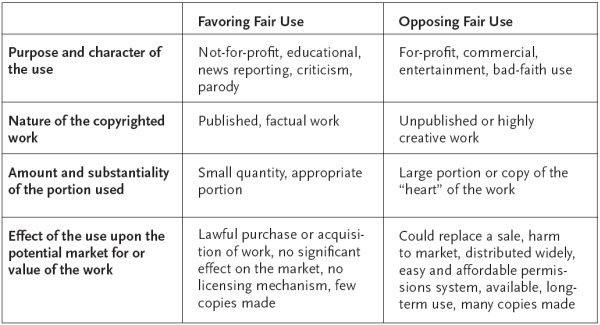

Although an exhaustive discussion of the concept of fair use is well beyond the scope of this chapter, ILL practitioners should familiarize themselves with this important part of the law. Table 4.1, inspired by Kenneth Crews’s Fair Use Checklist, helps illustrate how the four factors are considered by courts.

Table 4.1 Fair Use Checklist

Source: Adapted from Kenny Crews’s Fair Use Checklist, http://copyright.columbia.edu/copyright/fair-use/fair-use-checklist/.

LENDER RESPONSIBILITIES

Although lending libraries are not obliged to keep records for copyright purposes, most do so for statistical purposes. Lenders have a few obligations when it comes to responsibility for copyright compliance.

Lending libraries need to ensure that photocopy requests have indicated compliance with either CONTU guidelines (CCG) or another part of the copyright law (CCL), as discussed earlier. Lending libraries are obliged to return to the borrowing library requests that are missing this information rather than filling them.

Lenders need to reproduce the copyright notice that appears on the work, along with the work itself. This requirement complies with modifications made to Section 108 by provisions in the Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA) and in the Sonny Bono Copyright Term Extension Act of 1998. Most scholarly journal articles contain complete copyright information on at least the first page of the article itself. For older works, lenders may need to search for it, commonly in the front matter of the work. If no copyright notice can be found on the work, the lending library must include a notice similar to those that libraries used before the law changed.10 This requirement can mean keeping the old-fashioned, ubiquitous, inky copyright stamp adjacent to most ILL photocopiers. In the case of electronic document delivery, however, the copyright notice is automatically included with delivery.

Lending libraries also need to have a good working knowledge of the limitations on borrowing libraries. Any lending request that appears to break limitations set by CONTU or by Fair Use may be refused and returned to the borrower. Borrowers should indicate if permission to copy has been obtained through the Copyright Clearance Center or the publisher or otherwise provide information to the lender for exceptional requests.

Finally, lending libraries need to know what their licenses for electronic journals permit with regard to ILL. Electronic journal licenses can range from disallowing any form of ILL to permitting full electronic document delivery. Frequently, licenses permit lending but only by paper printout. If your library has such licenses, it would be beneficial to renegotiate them so that they match current technology and practice in order to comply with turnaround time agreements and modern electronic document delivery technologies.

ELECTRONIC DELIVERY

Paper copies are becoming increasingly obsolete. Most libraries deliver documents electronically, whether to their own patrons or to borrowing libraries. Borrowing libraries prefer to receive electronic copies. Naturally, this practice has possible copyright implications. The lending library must make a copy in order to send it to the borrowing library. However, this copy is deleted once it is received by the borrowing library. This procedure is parallel to the single (paper) copy becoming the property of the user, as specified by Section 108. On the borrowing side, documents are frequently posted on a password-protected website. The patron is normally limited to access within a specified time frame or limited to a set number of “views” of the document or both. However, the document can be printed or saved by the patron; thus, the single copy becomes the property of the user. In compliance with Section 108, libraries must not save copies of documents scanned for delivery to other libraries or provided for their patrons by other libraries; this could be construed as substitution for a subscription.11

ILL OF LICENSED ELECTRONIC JOURNALS

Increasingly, libraries license works—including electronic journals and electronic books—that formerly were purchased in print format.12 Because these are licensed works, they are subject to the terms of the license agreements, which fall under state contract law and not under copyright law, which is federal law. The contract’s provisions determine which state’s law applies.13

When libraries first began to acquire licensed works, many licenses did not permit ILL. Over time, licenses forbidding or severely restricting ILL would have a cumulative, deleterious effect on ILL as a whole. Increasingly, however, publishers, aggregators, and other providers are allowing ILL to some extent. In fact, according to studies conducted by the New York State–based IDS Project, less than 15 percent of licenses examined prohibited ILL under any circumstances.14 However, licenses may specify how ILL is conducted, which can fall into a variety of permutations. Among them are “print ILL only” or “must print out a copy before scanning for electronic delivery.” Although filling ILL requests directly from the electronic file is sometimes prohibited, many licenses allow direct electronic document delivery. Some licenses are silent regarding ILL. Many libraries assume tacit permission; others assume ILL is forbidden unless mentioned and specified. Collections of model licenses are being developed. Two such projects are NISO’s SERU (Shared E-Resource Understanding; www.niso.org/workrooms/seru/) and Yale’s Liblicense Model License Agreement (LMLA; www.library.yale.edu/~llicense/index.shtml). Library organizations offer negotiation workshops, and books and journal articles offer acquisitions staff assistance. Ideally, licenses should be negotiated (and in some cases renegotiated) so that any ILL process specified in the contract falls in line with the ILL department’s preferred, most efficient workflow.

Janet Brennan Croft describes three approaches typically used by ILL practitioners when faced with license contracts: (1) the avoidance approach, in which ILL departments lend nothing simply because the resource happens to be electronic; (2) the reactive approach, in which files are maintained on which resources permit lending and how that lending must be conducted; and (3) the proactive approach, in which licenses are negotiated with ILL permissions.15 Ideally, libraries would refuse to purchase a product that did not include ILL rights in the contract; however, practically, this approach might exclude necessary products from a library’s collection. ARL’s 1999 SPEC Kit on licenses indicated that 25 percent of libraries required ILL rights in the contract before signing it; this percentage is likely greater today.16 Georgia Harper advises librarians, “Very rarely do vendors refuse to negotiate their terms.”17

Finally, ILL practitioners, along with acquisitions staff and catalogers, should find a way to indicate license status so that lending staff know how to proceed when faced with a request from an electronic resource. Several vendors currently offer a wide variety of electronic resource management (ERM) products that assist not just ILL departments but other areas of the library as well. Open source ERM systems are also an option. Ideally, license codes such as the ones used by the IDS Project might someday be used in conjunction with ILL systems to indicate license requirements for lending requests and to simply deflect requests for (the few) sources from which ILL is not permitted.

NONBOOK FORMATS

Generally, materials in nonbook format (CDs, DVDs, VHS tapes, and other multimedia formats) fall under Section 109 and may be borrowed and loaned under the First Sale Doctrine. However, in some cases, multimedia materials are licensed to libraries rather than sold. These licenses may carry restrictions on lending, especially to outside institutions, and especially in school settings.18 As with other licensed works such as electronic journals, ILL practitioners should work with their acquisitions personnel to negotiate for ILL rights if possible and to ensure compliance with contract terms.

INTERNATIONAL COPYRIGHT ISSUES

“The Convention for the Protection of Literary and Artistic Works” was signed in Berne, Switzerland, on September 9, 1886 (www.wipo.int/treaties/en/ip/berne/index.html). Otherwise known as the Berne Convention, this document supports international ILL. In 1988, the United States joined the Berne Convention, and all members of the European Union are also current signatories. Article 9, Right of Reproduction, states: “It shall be a matter for legislation in the countries of the Union to permit the reproduction of such works in certain special cases, provided that such reproduction does not conflict with a normal exploitation of the work and does not unreasonably prejudice the legitimate interests of the author.” In order to conform to the Berne Convention standards, countries had to standardize some of their intellectual property laws. This work is still unfinished, and many countries’ laws only partially conform.19

IFLA’s International Resource Sharing and Document Delivery: Principles and Guidelines for Procedure, first agreed to by IFLA in 1954, was revised in February 2009 (www.ifla.org/files/docdel/documents/international-lending-en.pdf). It contains eight principles and guidelines; copyright is number six. It advises: “Due regard must be given to the copyright laws of the supplying country. While material requested on international ILL may often fall within ‘fair use’ or ‘fair dealing’ provisions, responsibility rests with the supplying library to inform the requesting library of any copyright restrictions which might apply.” It continues in sections:

6.2. Each supplying library should be aware of, and work within, the copyright laws of its own country. In addition, the supplying library should ensure that any relevant copyright information is made available and communicated to requesting libraries.

6.3. Lending, and limited copying for purposes such as education, research or private study, are usually exceptions within national copyright legislation. The supplying library should inform the requesting library of these exceptions.

6.4. The requesting library should pay due regard to the copyright laws of the supplying library’s country.

6.5. Each supplying library must abide by any licenses agreed to by their organisation, which may place some restrictions on the use of electronic resources for ILL transactions.

This document also refers to the IFLA Position on Copyright in the Digital Environment (revised January 25, 2001), which asserts that “digital is not different.” It affirms the rights supported by the Berne Convention and treaties by the World Intellectual Property Organisation (WIPO). It states, “Contractual provisions, for example within licensing agreements, should not override reasonable lending of electronic resources by library and information staff” (http://archive.ifla.org/V/press/copydig.htm).

Despite harmonization efforts, Canadian libraries, for example, cannot deliver documents electronically to users. Section 30.2(5) of the Canadian Copyright Act states: “The copy given to the patron must not be in digital form.”20 As Canadian libraries continue to lobby their government for changes to allow electronic delivery, the Canada Institute for Scientific and Technical Information (CISTI) worked with CCC to license the right to provide electronic delivery for most journal titles.21 Although ILL between countries is clearly encouraged, differences in copyright laws between countries are likely to continue to affect efficient ILL practice, at least in minor ways. The ILL practitioner can cope by establishing good working relationships with international libraries.

APPENDIX 4.1

Abridged Full Text of United States Copyright Law, Title 17, Sections 106–109

Complete text may be found at www.copyright.gov/title17/.

§ 106 · Exclusive rights in copyrighted works

Subject to sections 107 through 122, the owner of copyright under this title has the exclusive rights to do and to authorize any of the following:

(1) to reproduce the copyrighted work in copies or phonorecords;

(2) to prepare derivative works based upon the copyrighted work;

(3) to distribute copies or phonorecords of the copyrighted work to the public by sale or other transfer of ownership, or by rental, lease, or lending;

(4) in the case of literary, musical, dramatic, and choreographic works, pantomimes, and motion pictures and other audiovisual works, to perform the copyrighted work publicly;

(5) in the case of literary, musical, dramatic, and choreographic works, pantomimes, and pictorial, graphic, or sculptural works, including the individual images of a motion picture or other audiovisual work, to display the copyrighted work publicly; and

(6) in the case of sound recordings, to perform the copyrighted work publicly by means of a digital audio transmission.

§ 107 · Limitations on exclusive rights: Fair use

Notwithstanding the provisions of sections 106 and 106A, the fair use of a copyrighted work, including such use by reproduction in copies or phonorecords or by any other means specified by that section, for purposes such as criticism, comment, news reporting, teaching (including multiple copies for classroom use), scholarship, or research, is not an infringement of copyright. In determining whether the use made of a work in any particular case is a fair use the factors to be considered shall include—

(1) the purpose and character of the use, including whether such use is of a commercial nature or is for nonprofit educational purposes;

(2) the nature of the copyrighted work;

(3) the amount and substantiality of the portion used in relation to the copyrighted work as a whole; and

(4) the effect of the use upon the potential market for or value of the copyrighted work.

The fact that a work is unpublished shall not itself bar a finding of fair use if such finding is made upon consideration of all the above factors.

§ 108 · Limitations on exclusive rights:

Reproduction by libraries and archives

(a) Except as otherwise provided in this title and notwithstanding the provisions of section 106, it is not an infringement of copyright for a library or archives, or any of its employees acting within the scope of their employment, to reproduce no more than one copy or phonorecord of a work, except as provided in subsections (b) and (c), or to distribute such copy or phonorecord, under the conditions specified by this section, if—

(1) the reproduction or distribution is made without any purpose of direct or indirect commercial advantage;

(2) the collections of the library or archives are (i) open to the public, or (ii) available not only to researchers affiliated with the library or archives or with the institution of which it is a part, but also to other persons doing research in a specialized field; and

(3) the reproduction or distribution of the work includes a notice of copyright that appears on the copy or phonorecord that is reproduced under the provisions of this section, or includes a legend stating that the work may be protected by copyright if no such notice can be found on the copy or phonorecord that is reproduced under the provisions of this section.

(b) The rights of reproduction and distribution under this section apply to three copies or phonorecords of an unpublished work duplicated solely for purposes of preservation and security or for deposit for research use in another library or archives of the type described by clause (2) of subsection (a), if—

(1) the copy or phonorecord reproduced is currently in the collections of the library or archives; and

(2) any such copy or phonorecord that is reproduced in digital format is not otherwise distributed in that format and is not made available to the public in that format outside the premises of the library or archives.

(c) The right of reproduction under this section applies to three copies or phonorecords of a published work duplicated solely for the purpose of replacement of a copy or phonorecord that is damaged, deteriorating, lost, or stolen, or if the existing format in which the work is stored has become obsolete, if—

(1) the library or archives has, after a reasonable effort, determined that an unused replacement cannot be obtained at a fair price; and

(2) any such copy or phonorecord that is reproduced in digital format is not made available to the public in that format outside the premises of the library or archives in lawful possession of such copy.

For purposes of this subsection, a format shall be considered obsolete if the machine or device necessary to render perceptible a work stored in that format is no longer manufactured or is no longer reasonably available in the commercial marketplace.

(d) The rights of reproduction and distribution under this section apply to a copy, made from the collection of a library or archives where the user makes his or her request or from that of another library or archives, of no more than one article or other contribution to a copyrighted collection or periodical issue, or to a copy or phonorecord of a small part of any other copyrighted work, if—

(1) the copy or phonorecord becomes the property of the user, and the library or archives has had no notice that the copy or phonorecord would be used for any purpose other than private study, scholarship, or research; and

(2) the library or archives displays prominently, at the place where orders are accepted, and includes on its order form, a warning of copyright in accordance with requirements that the Register of Copyrights shall prescribe by regulation.

(e) The rights of reproduction and distribution under this section apply to the entire work, or to a substantial part of it, made from the collection of a library or archives where the user makes his or her request or from that of another library or archives, if the library or archives has first determined, on the basis of a reasonable investigation, that a copy or phonorecord of the copyrighted work cannot be obtained at a fair price, if—

(1) the copy or phonorecord becomes the property of the user, and the library or archives has had no notice that the copy or phonorecord would be used for any purpose other than private study, scholarship, or research; and

(2) the library or archives displays prominently, at the place where orders are accepted, and includes on its order form, a warning of copyright in accordance with requirements that the Register of Copyrights shall prescribe by regulation.

(f) Nothing in this section—

(1) shall be construed to impose liability for copyright infringement upon a library or archives or its employees for the unsupervised use of reproducing equipment located on its premises: Provided, That such equipment displays a notice that the making of a copy may be subject to the copyright law;

(2) excuses a person who uses such reproducing equipment or who requests a copy or phonorecord under subsection (d) from liability for copyright infringement for any such act, or for any later use of such copy or phono-record, if it exceeds fair use as provided by section 107;

(3) shall be construed to limit the reproduction and distribution by lending of a limited number of copies and excerpts by a library or archives of an audiovisual news program, subject to clauses (1), (2), and (3) of subsection (a); or

(4) in any way affects the right of fair use as provided by section 107, or any contractual obligations assumed at any time by the library or archives when it obtained a copy or phonorecord of a work in its collections.

(g) The rights of reproduction and distribution under this section extend to the isolated and unrelated reproduction or distribution of a single copy or phonorecord of the same material on separate occasions, but do not extend to cases where the library or archives, or its employee—

(1) is aware or has substantial reason to believe that it is engaging in the related or concerted reproduction or distribution of multiple copies or phonorecords of the same material, whether made on one occasion or over a period of time, and whether intended for aggregate use by one or more individuals or for separate use by the individual members of a group; or

(2) engages in the systematic reproduction or distribution of single or multiple copies or phonorecords of material described in subsection (d): Provided, That nothing in this clause prevents a library or archives from participating in interlibrary arrangements that do not have, as their purpose or effect, that the library or archives receiving such copies or phonorecords for distribution does so in such aggregate quantities as to substitute for a subscription to or purchase of such work.

(h)

(1) For purposes of this section, during the last 20 years of any term of copyright of a published work, a library or archives, including a nonprofit educational institution that functions as such, may reproduce, distribute, display, or perform in facsimile or digital form a copy or phonorecord of such work, or portions thereof, for purposes of preservation, scholarship, or research, if such library or archives has first determined, on the basis of a reasonable investigation, that none of the conditions set forth in subparagraphs (A), (B), and (C) of paragraph (2) apply.

(2) No reproduction, distribution, display, or performance is authorized under this subsection if—

(A) the work is subject to normal commercial exploitation;

(B) a copy or phonorecord of the work can be obtained at a reasonable price; or

(C) the copyright owner or its agent provides notice pursuant to regulations promulgated by the Register of Copyrights that either of the conditions set forth in subparagraphs (A) and (B) applies.

(3) The exemption provided in this subsection does not apply to any subsequent uses by users other than such library or archives.

(i) The rights of reproduction and distribution under this section do not apply to a musical work, a pictorial, graphic or sculptural work, or a motion picture or other audiovisual work other than an audiovisual work dealing with news, except that no such limitation shall apply with respect to rights granted by subsections (b), (c), and (h), or with respect to pictorial or graphic works published as illustrations, diagrams, or similar adjuncts to works of which copies are reproduced or distributed in accordance with subsections (d) and (e).

§ 109 · Limitations on exclusive rights:

Effect of transfer of particular copy or phonorecord

(a) Notwithstanding the provisions of section 106(3), the owner of a particular copy or phonorecord lawfully made under this title, or any person authorized by such owner, is entitled, without the authority of the copyright owner, to sell or otherwise dispose of the possession of that copy or phonorecord. Notwithstanding the preceding sentence, copies or phonorecords of works subject to restored copyright under section 104A that are manufactured before the date of restoration of copyright or, with respect to reliance parties, before publication or service of notice under section 104A(e), may be sold or otherwise disposed of without the authorization of the owner of the restored copyright for purposes of direct or indirect commercial advantage only during the 12-month period beginning on—

(1) the date of the publication in the Federal Register of the notice of intent filed with the Copyright Office under section 104A(d)(2)(A), or

(2) the date of the receipt of actual notice served under section 104A(d)(2)(B), whichever occurs first.

(b)

(1)

(A) Notwithstanding the provisions of subsection (a), unless authorized by the owners of copyright in the sound recording or the owner of copyright in a computer program (including any tape, disk, or other medium embodying such program), and in the case of a sound recording in the musical works embodied therein, neither the owner of a particular phonorecord nor any person in possession of a particular copy of a computer program (including any tape, disk, or other medium embodying such program), may, for the purposes of direct or indirect commercial advantage, dispose of, or authorize the disposal of, the possession of that phono-record or computer program (including any tape, disk, or other medium embodying such program) by rental, lease, or lending, or by any other act or practice in the nature of rental, lease, or lending. Nothing in the preceding sentence shall apply to the rental, lease, or lending of a phonorecord for nonprofit purposes by a nonprofit library or nonprofit educational institution.

The transfer of possession of a lawfully made copy of a computer program by a nonprofit educational institution to another nonprofit educational institution or to faculty, staff, and students does not constitute rental, lease, or lending for direct or indirect commercial purposes under this subsection.

(B) This subsection does not apply to—

(i) a computer program which is embodied in a machine or product and which cannot be copied during the ordinary operation or use of the machine or product; or

(ii) a computer program embodied in or used in conjunction with a limited purpose computer that is designed for playing video games and may be designed for other purposes.

(C) Nothing in this subsection affects any provision of chapter 9 of this title.

(2)

(A) Nothing in this subsection shall apply to the lending of a computer program for nonprofit purposes by a nonprofit library, if each copy of a computer program which is lent by such library has affixed to the packaging containing the program a warning of copyright in accordance with requirements that the Register of Copyrights shall prescribe by regulation.

(B) Not later than three years after the date of the enactment of the Computer Software Rental Amendments Act of 1990, and at such times thereafter as the Register of Copyrights considers appropriate, the Register of Copyrights, after consultation with representatives of copyright owners and librarians, shall submit to the Congress a report stating whether this paragraph has achieved its intended purpose of maintaining the integrity of the copyright system while providing nonprofit libraries the capability to fulfill their function. Such report shall advise the Congress as to any information or recommendations that the Register of Copyrights considers necessary to carry out the purposes of this subsection.

(3) Nothing in this subsection shall affect any provision of the antitrust laws. For purposes of the preceding sentence, “antitrust laws” has the meaning given that term in the first section of the Clayton Act and includes section 5 of the Federal Trade Commission Act to the extent that section relates to unfair methods of competition.

(4) Any person who distributes a phonorecord or a copy of a computer program (including any tape, disk, or other medium embodying such program) in violation of paragraph (1) is an infringer of copyright under section 501 of this title and is subject to the remedies set forth in sections 502, 503, 504, and 505. Such violation shall not be a criminal offense under section 506 or cause such person to be subject to the criminal penalties set forth in section 2319 of title 18.

(c) Notwithstanding the provisions of section 106(5), the owner of a particular copy lawfully made under this title, or any person authorized by such owner, is entitled, without the authority of the copyright owner, to display that copy publicly, either directly or by the projection of no more than one image at a time, to viewers present at the place where the copy is located.

(d) The privileges prescribed by subsections (a) and (c) do not, unless authorized by the copyright owner, extend to any person who has acquired possession of the copy or phonorecord from the copyright owner, by rental, lease, loan, or otherwise, without acquiring ownership of it.

(e) Notwithstanding the provisions of sections 106(4) and 106(5), in the case of an electronic audiovisual game intended for use in coin-operated equipment, the owner of a particular copy of such a game lawfully made under this title, is entitled, without the authority of the copyright owner of the game, to publicly perform or display that game in coin-operated equipment, except that this subsection shall not apply to any work of authorship embodied in the audiovisual game if the copyright owner of the electronic audiovisual game is not also the copyright owner of the work of authorship.

NOTES

1. Lee Andrew Hilyer, “Copyright in the Interlibrary Loan Department,” Interlibrary Loan and Document Delivery: Best Practices for Operating and Managing Interlibrary Loan Services in All Libraries (New York: Haworth Press, 2006), 53–64. Simultaneously published in Journal of Interlibrary Loan, Document Delivery, and Electronic Reserve 16, no. 1–2 (2006).

2. American Library Association, Interlibrary Loans: ALA Library Fact Sheet Number 8, www.ala.org/ala/professionalresources/libfactsheets/alalibraryfactsheet08.cfm.

3. Carrie Russell, Complete Copyright: An Everyday Guide for Librarians (Chicago: American Library Association, 1994).

4. New York Times, Deaths: Judge Stanley H. Fuld, July 27, 2003, www.nytimes.com/2003/07/27/classified/paid-notice-deaths-fuld-judge-stanley-h.html?pagewanted=1.

5. CONTU (National Commission on New Technological Uses of Copyright Works), Final Report of the National Commission on New Technological Uses of Copyright Works, July 31, 1978, Library of Congress, Washington, DC, 1979, 47–48, http://digital-law-online.info/CONTU/PDF/index.html.

6. Russell, Complete Copyright.

7. Hilyer, “Copyright in the Interlibrary Loan Department,” 53–64.

8. CONTU, 55.

9. Laura Gasaway, “Questions and Answers: Copyright Column,” Against the Grain 17, no. 6 (2005): 61-62.

10. Georgia Harper, Copyright Crash Course: Copyright in the Library; Interlibrary Loan, www.utsystem.edu/ogc/intellectualproperty/l-108g.htm.

11. Janet Brennan Croft, “Interlibrary Loan and Licensing: Tools for Proactive Contract Management,” in Licensing in Libraries: Practical and Ethical Aspects, ed. Karen Rupp-Serrano, 41–53 (New York: Haworth Press, 2005). Simultaneously published in Journal of Library Administration 42, no. 3–4 (2005): 41–53.

12. Harper, Copyright Crash Course.

13. Donna Nixon, “Copyright and Interlibrary Loan Rights,” Journal of Interlibrary Loan, Document Delivery and Information Supply 13, no. 3 (2003): 69.

14. IDS Project (New York: SUNY Geneseo), www.idsproject.org/index.aspx.

15. Croft, “Interlibrary Loan and Licensing.”

16. Ibid., 50.

17. Quoted in Croft, “Interlibrary Loan and Licensing,” 51.

18. Carol Simpson, “Interlibrary Loan of Audiovisuals May Bring a Lawsuit,” Library Media Connection 26, no. 5 (February 2008): 26–30.

19. Cristine Martins and Sophia Martins, “Electronic Copyright in a Shrinking World,” Computers in Libraries 22, no. 5 (2002): 31.

20. Robert Tiessen, “Copyright’s Effect on Interlibrary Loan in Canada and the United States,” Journal of Interlibrary Loan, Document Delivery and Electronic Reserve 18, no. 1 (2007): 101–11.

21. Ibid., 104.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

American Library Association. Interlibrary Loans. ALA Library Fact Sheet Number 8. www.ala.org/ala/professionalresources/libfactsheets/alalibraryfactsheet08.cfm.

CONTU (National Commission on New Technological Uses of Copyright Works). Final Report of the National Commission on New Technological Uses of Copyright Works, July 31, 1978. Washington, DC: Library of Congress, 1979. www.cni.org/docs/infopols/CONTU.html or http://digital-law-online.info/CONTU/PDF/index.html.

Crews, Kenneth. Fair Use Checklist. New York: Columbia University Libraries/Information Services, Copyright Advisory Office. http://copyright.columbia.edu/copyright/fair-use/fair-use-checklist/.

Croft, Janet Brennan. Legal Solutions in Electronic Reserves and in the Electronic Delivery of Interlibrary Loan. New York: Haworth Press, 2004. Simultaneously published in Journal of Interlibrary Loan, Document Delivery and Information Supply 14, no. 3 (2004).

———. “Interlibrary Loan and Licensing: Tools for Proactive Contract Management.” In Licensing in Libraries: Practical and Ethical Aspects, edited by Karen Rupp-Serrano, 41–53. New York: Haworth Press, 2005. Simultaneously published in Journal of Library Administration 42, no. 3–4 (2005): 41–53.

Gasaway, Laura. “Questions and Answers: Copyright Column.” Against the Grain 17, no. 6 (2005): 61–62.

Harper, Georgia. Copyright Crash Course: Copyright in the Library; Interlibrary Loan. www.utsystem.edu/ogc/intellectualproperty/l-108g.htm.

Hilyer, Lee Andrew. “Copyright in the Interlibrary Loan Department.” Interlibrary Loan and Document Delivery: Best Practices for Operating and Managing Interlibrary Loan Services in All Libraries. New York: Haworth Press, 2006, 53–64. Simultaneously published in Journal of Interlibrary Loan, Document Delivery and Electronic Reserve 16, no. 1–2 (2006).

IDS Project. New York: SUNY Geneseo. www.idsproject.org/index.aspx.

Martins, Cristine, and Sophia Martins. “Electronic Copyright in a Shrinking World.” Computers in Libraries 22, no. 5 (2002): 28–31.

New York Times. Deaths. Judge Stanley H. Fuld, July 27, 2003. www.nytimes.com/2003/07/27/classified/paid-notice-deaths-fuld-judge-stanley-h.html?pagewanted=1.

Nixon, Donna. “Copyright and Interlibrary Loan Rights.” Journal of Interlibrary Loan, Document Delivery and Information Supply 13, no. 3 (2003): 55–89.

Russell, Carrie. Complete Copyright: An Everyday Guide for Librarians. Chicago: American Library Association, 1994.

Simpson, Carol. “Interlibrary Loan of Audiovisuals May Bring a Lawsuit.” Library Media Connection 26, no. 5 (February 2008): 26–30.

Tiessen, Robert. “Copyright’s Effect on Interlibrary Loan in Canada and the United States.” Journal of Interlibrary Loan, Document Delivery and Electronic Reserve 18, no. 1 (2007): 101–11.