MANAGEMENT OF INTERLIBRARY LOAN

Jennifer Kuehn

Managing an interlibrary loan unit requires the ability to manage change. Interlibrary loan is done very differently now than it was even a decade ago. Automation, the information landscape, users’ expectations, and the tools we have at our disposal to meet patrons’ needs have changed, and these changes have influenced interlibrary loan practice. As more libraries implemented automated ILL management systems, two functions that once took a great deal of time became unnecessary: keeping manual files and keying data. Freed from filing, ILL units have been able to make tremendous improvements in productivity and enhancements of the services they provide. The past two decades have also seen an increase in overall request volume.

An interlibrary loan office is a vibrant unit, working with and impacted by so many other functions of the library. As a public service, it works directly with patrons and relies on other units within the local library to be able to perform its work. One example of this interdependency with other library units is extensive use of the online catalog and integrated library system (ILS). Is there another unit in the library that searches the catalog as often as interlibrary loan? Interlibrary loan might be viewed as the library’s biggest user of the catalog, possibly having more material checked out to it than to any single, local patron.

But how do we manage and advance the service we provide? The most important strategy is to look for opportunities to consider how something could be done a different way. Listen to what your patrons say and get involved professionally to learn what your peers are doing and why. Look at your own workflows. Consider what you are doing well to build on your strengths and review your weaknesses to see where you can improve. Consider your mission and develop goals with an understanding of the costs involved in meeting them. You may want to use the Rethinking Resource Sharing initiative and its seven principles as a starting point and ask what you might do to reduce the barriers to service for users. The Rethinking Resource Sharing initiative (http://rethinkingresourcesharing.org/manifesto.html) aims to foster an updated framework of cooperation and collaboration and to encourage libraries to find new ways to serve their patrons as well as all potential users.

Interlibrary loan management almost always involves managing at least two distinct services: borrowing and lending. An interlibrary loan borrowing operation typically obtains specific items when a patron’s needs aren’t met by the local collection. Traditionally, this service has been provided by borrowing materials from other libraries, but the department may also obtain items in other ways. Increasingly, ILL units are directing patrons to available local print or online content, purchasing items for the collection on demand, purchasing an item that is given to the individual requestor to keep, or obtaining an item directly from an author, publisher, association, or cultural heritage organization. These varied approaches go beyond simply borrowing from other libraries to “get it” for the patron from whatever source can be found. Sometimes, ILL serves as a gatekeeper by determining by policy just how far the library will go to meet a patron’s request. That’s an area where the management of interlibrary loan both directs and reflects practice.

Management of a lending operation is the other side of the coin because we are serving other libraries’ patrons with our collection. Borrowing can only be successful if there are lending libraries to fill requests. Even though there are more choices of sources in borrowing than simply requesting from another library, the sharing of resources between libraries continues to grow.

Our library community has embraced the idea that access complements ownership. Improving that access includes improving lending operations, which in turn allows us to confidently tell our patrons that we can get it for them, thereby meeting the raised user expectations in an environment of increased access. This chapter will explore five aspects of ILL management: the ILL environment, policy development, assessment, staffing and human resources, and working with other units in the library.

THE ILL ENVIRONMENT

Managing an ILL unit requires careful consideration of the changes taking place in other library services. Additionally, keep in mind that other commercial services increase patrons’ expectations for interlibrary service. Traditional library-to-library interlibrary loan is not the only option for patrons when something is unavailable locally. Internet booksellers are ubiquitous, and patrons may use multiple libraries (public libraries, for example, also serve college and university patrons). When a patron’s own institution does not have something available, other resource-sharing services may exist that would be preferred to interlibrary loan, such as patron-initiated borrowing through a consortial catalog. Consortia of all kinds have been developed that enhance and streamline sharing among libraries, particularly for returnable materials. Examples of these cooperatives include I-Share in Illinois, OhioLINK in Ohio, MeLCat in Michigan, and Orbis Cascade’s Summit in Washington State and Oregon. Some of these consortia consist of multiple library types enriching the assortment of material readily available for patrons through one union catalog. Despite the variety of potential suppliers, no one consortium, like no one library, has everything, so traditional interlibrary services are still needed.

Patrons’ expectations have changed, too. The universe of what a patron can discover has greatly expanded, and patrons have come to expect levels of service for ease of requesting and speed of delivery that rarely existed a dozen years ago. If a user can request a book from other libraries within a state, monitor that it’s been found and shipped, and know that it will likely arrive within a few days and be delivered to an office or preferred convenient library, that user may expect ILL to approximate the same process. With the growth of article citation databases and electronic journals, patrons see that it is possible to purchase an article directly from a publisher with a credit card, raising patrons’ expectations of how quickly materials can be obtained.

As a manager for interlibrary services, you have many resources to support your work. In your own institution there are many people with whom you will want and need to interact, which will be discussed later in this chapter. But outside your library there are many colleagues for you to meet who are doing similar work in libraries not unlike yours. There are electronic discussion lists, journals, and conferences focused solely on interlibrary services and resource sharing. Within the American Library Association, STARS (Sharing and Transforming Access to Resources Section) is a section of RUSA (Reference and User Services Association) and brings together librarians and library staff members for activities at conferences and committee work throughout the year. If you subscribe to state or national interlibrary loan e-mail discussion groups, you can check the archives to see how a topic has been addressed in the past and then post questions. Another strategy for professional development is to find peers in your area and visit their “shop.” Such visits not only foster collegial relationships but also help you reflect on what you might do differently in your environment. State, regional, and local library groups may also have interlibrary loan groups or be able to connect you to colleagues. Simply put, a best practice is to become a part of the interlibrary loan community. As people who share resources professionally, it is a community that willingly shares its knowledge, too.

POLICY DEVELOPMENT

Interlibrary loan policy development requires looking at the departmental and library-wide environment, considering the mission of the library, and then aligning policies with service goals. A good place to start is by reviewing the Interlibrary Loan Code for the United States. The purpose of the code is to describe “the responsibilities of libraries to each other when requesting material for users.”1 The code has a long history as a guiding principle for interlibrary loan.

The U.S. Interlibrary Loan Code, first published in 1917 and adopted by the American Library Association in 1919, is designed to provide a code of behavior for requesting and supplying material within the United States. This code does not override individual or consortial agreements or regional or state codes that may be more liberal or more prescriptive. This national code is intended to provide guidelines for exchanges between libraries where no other agreement applies. The code is intended to be adopted voluntarily by U.S. libraries and is not enforced by an oversight body. However, as indicated later in this chapter, supplying libraries may suspend service to borrowing libraries that fail to comply with the provisions of this code.

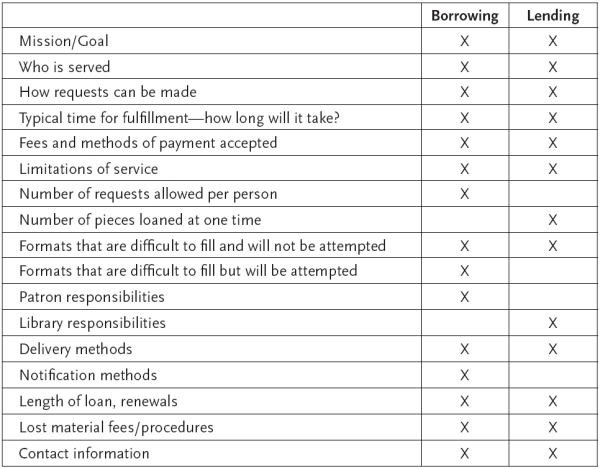

In addition to the U.S. Interlibrary Loan Code, states, regions, or other library cooperatives may have policies or service expectations that should be reviewed. Next, review your existing policies and any written statements that may already guide current practice. When examining policies, look at the who, what, where, how, and why of the service, both in the present and what it might be in the future, keeping in mind that interlibrary services can showcase a commitment to meeting patrons’ needs. Generally speaking, policies do not vary greatly from library to library. Many libraries have similar policies with small differences reflecting goals, the need to limit costs, or the number of available staff. Some of the elements of interlibrary loan policies are illustrated in table 5.1, which shows that borrowing and lending policies are quite parallel.

Table 5.1 Interlibrary Loan Policy Elements

Whom Do You Serve?

In academic libraries, the primary clientele are usually faculty (including emeritus and visiting faculty), staff, and students. If you prohibit a specific type of user (e.g., undergraduates), it is not uncommon for the determined user to seek others to act as a proxy. Serving all without any distinction prevents this unnecessary ruse. Additional clientele that might be served include alumni, businesses, or patrons from the community who may or may not have a formal relationship with the institution. And although individuals might be the typical users, research work groups and projects can be served, too, usually with one person named for pickup and delivery. You will want to define your primary constituents but be open to considering others who might be your customers, too. Your institution’s service philosophy and level of commitment to reaching out beyond the primary clientele may help guide your decision.

Public libraries typically serve local residents and other cardholding patrons, which may include businesses or groups such as book clubs. The public library serves people in all aspects of their lives, including personal interests, work-related needs, or lifelong learning pursuits. More often than in academic libraries, public libraries might ask the requestor to pay the fees associated with borrowing. School and corporate libraries also engage in resource-sharing activities, but special and corporate libraries may have fewer opportunities to partner with other libraries in terms of consortial catalogs, leaving traditional interlibrary loan as the model used to meet their clients’ needs.

What Will You Borrow? What Will It Cost?

After you have developed an overarching service goal, decide what you will do for your patrons. You can choose how far you’ll go for a patron, how much you are willing to subsidize requests, or how much support you will provide for one patron over time or a research project. Setting service limits may be difficult, but it’s easier to set by policy in advance than when a request comes in.

In addition to borrowing from another library, many options now exist for procuring an item for a patron. Resource discovery is easier for patrons, resulting in requests for material types that are new, different, and possibly not appropriate for loan. Ongoing review and updating of policies will be necessary as barriers to what can be obtained break down. For example, as it becomes easier to find a source, make requests, and pay for them internationally, it will be easier to extend borrowing practice to include international ILL. As you are able to ease restrictions on borrowing, it may also make sense to remove them in lending.

Your policy should also list the types of material that may be difficult or impossible to get through interlibrary loan. That list might include many types of materials: old, rare, items of high value, whole issues or volumes of serials, reference books, computer manuals, genealogy books, new publications or those in high demand, manuscripts, screenplays, scripts, scores, multivolume sets, phono-records, media (e.g., VHS tapes, DVDs, CDs), and theses or dissertations. You might address how you will handle requests for things not yet published, as users frequently find works that are not yet available. Those requests could be canceled outright or referred to collection development staff.

It is important to distinguish between hard-to-get materials and what you won’t even try to obtain. However, keep in mind that an increasing number of formerly rare material types can now be obtained, though it may require more work. Libraries are also more willing to borrow material that is already owned by the library but in use by another patron, in a noncirculating collection, or at the bindery. As interlibrary borrowing becomes faster, it may be quicker to borrow a copy from elsewhere rather than wait for the library’s own copy to be returned through a recall or due date. This willingness to borrow more stems from how much easier it is to make requests as well as a trend toward longer due dates and more flexible circulation practices. Academic libraries are still debating whether textbooks should be borrowable. Some institutions consider textbook purchases to be part of the students’ responsibility while others may be more willing to get whatever their patrons need. Academic libraries are also increasingly willing to subsidize recreational interests of their clientele, rather than just supporting scholarly interests, especially as it is often difficult to distinguish between the two. These issues should be addressed in your policy.

How Do Users Place Requests? How Do Patrons Receive Requested Materials?

Determining which methods of requesting to allow requires balancing the needs of users, staff workload, and costs. You may allow requests from paper or online request forms, e-mail, telephone, or WorldCat or via OpenURL from article databases. However, streamlining request processes can reduce errors and workload, while still providing acceptable service to users. For example, being able to accept requests over the telephone does not necessarily mean that the department should choose to make this a service option. Inform your patrons of the various methods by which to submit requests in a variety of places, especially at their point of discovery. It is also important to work with library administration to obtain support and understanding for the scope of service, and then share the final product with other library staff members who work directly with patrons (e.g., reference, instruction, and circulation units).

You may want to include a statement about patron responsibility for fines, late returns, damaged materials, or lost items, noting that failure to return materials on time may damage the relationship with other libraries and compromise the ability to borrow in the future. It is also important to note that the loan period is set by the lender. Patrons also need to know if you will renew and if so, for how long, your methods of delivery or pickup, and how patrons will be notified about the arrival of their request. Lee Hilyer provides a nice sample fee FAQ in his book.2 Although patrons do not always read these policy statements, it is still a best practice to make the information available.

How Long Will It Take? How Much Does It Cost the User?

Patrons typically ask two things about the service: How long will it take? and How much do I have to pay? The answer to “how long” may be unknown for any one request because we can’t really predict the future, but giving a general or average answer is helpful to shape expectations. Although patrons may see increasingly faster turnaround time for articles because of electronic delivery, loans must be shipped and will often take longer to obtain.

Your library may subsidize the cost of providing interlibrary loan because of the library’s philosophy that the service is a necessary extension of the collection to support users’ needs. Other libraries may not have this luxury or may be forced to set limits. One option is to charge a flat fee to users for each request. Another option is to offer the service with the expectation that patrons will pay any lending or copyright fees associated with their request. Still other options are to charge in specific circumstances, such as for dissertations ordered on demand, materials requested but not picked up, or overdue fees. Some libraries ask for a maximum cost the patron is willing to pay, although such libraries try to get the material from free sources first. By asking the question upfront at the point where the user places the request, staff members do not have to contact the patron for permission to continue pursuing the request with lending libraries that charge. If any component of your service might require a payment from a user, make it clear in your written policies. Keep in mind, however, that collecting fees is not without cost for the library, both in staff time to manage the process and in bank fees associated with credit card or check payments.

What about Lending Policies?

Although it is tempting to focus on your own patrons, it is important not to omit lending activities when creating or revising policies. Although the OCLC Policies Directory currently is the primary place to display this information for thousands of libraries, a lending website is a smart addition, particularly for high-volume lenders or for those with unique collections that may be sought after by libraries that do not utilize OCLC. Although not all borrowing libraries will see your lending website or look up your information in the OCLC Policies Directory, having it available and up to date makes you a better partner. You should answer the basic questions about your lending activities (the who, what, where, when, and how of your service) on a web page as well as in the OCLC Policies Directory. A lending web page can also be a good place to showcase unique services like digitizing on demand, maintaining an institutional repository of electronic theses and dissertations (ETDs), your willingness to copy or provide reference service from genealogy collections, or lending from special collections. University libraries should articulate their policy on lending theses or dissertations or both, particularly if purchasing copies from ProQuest is an alternative, because borrowing libraries may be unfamiliar with that option.

The most important element to include in your lending policy is basic contact information: library name, institution name, what you call your unit, address(es), e-mail, phone and fax numbers, hours, holiday closures, and the like. For larger units, make it clear who to contact for various services. Parallel to the information you provide in a borrowing policy, include the various methods by which you are willing to accept requests (e.g., by phone, fax, e-mail, WorldCat Resource Sharing, or web form). Outline the collections your unit will not loan at all. Some libraries are unable to loan bound serials, audiovisual material, government documents, or other unique collections. Explain the various delivery methods you use when loaning your materials and the shipping method you want borrowers to use when returning materials. You may have multiple methods of delivery for photocopies, including Odyssey, Ariel, fax, mail, as e-mail attachments, or posting the articles you lend on a server and allowing borrowing libraries to retrieve them from a link provided in an e-mail notification. For microforms or for multivolume sets of books, you might limit the number of pieces you will lend at one time on a single request in order to reduce possible loss or because of shipping cost considerations. Delivery services such as FedEx and UPS offer tracking and make loss less likely, so you might offer varying limits.

Describe your fee structure and the methods of payment accepted, including your fees and the process for replacing items that get lost in a transaction. Fees can be established to reduce demand, to offer pricing comparable to that of peer institutions, or to recover actual and indirect costs incurred for lending activities. If you are lending internationally, the International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions (IFLA) has a voucher system with reusable plastic payment cards (see http://archive.ifla.org/VI/2/p1/vouchers.htm). Libraries are encouraged, but not required, to accept one voucher as payment for a single loan or photocopy. The scheme reduces the need for invoices, bank fees, and loss of revenue through currency exchange. If you are willing to accept IFLA vouchers for payment, you then have them on hand when you need them for borrowing.

An increasing number of libraries are reconsidering the standard loan period. Lengthening the loan period may reduce the number of renewals requested and the workload that accompanies renewal processing. Some libraries also choose to extend the loan period and decline to grant renewals. An alternative workflow that some libraries employ is to convert lending requests into digitization-on-demand requests for materials in the public domain. The borrowing library pays for the digitization and the lending library fills the request but then makes the work freely available. If a library digitizes material, it is helpful to add the URL for the digital version to the OCLC cataloging record to assist in its discovery and use by others.

ASSESSMENT

The Association of Research Libraries (ARL) has conducted three major studies that have provided important baseline data for interlibrary loan service evaluation. These studies developed instruments for measuring costs in order to make comparisons across institutions. In addition to cost data, the studies provide us with the best practices of high-performing libraries that can be adopted by others.

The first, a cost study, was done in 1992 as a joint project of ARL and the Research Libraries Group (RLG) and had seventy-six participants from the United States and Canada.3 Researchers learned that staff costs accounted for 77 percent of total transaction cost (combined borrowing and lending). The second study was conducted in 1996 with 119 participants—ninety-seven research libraries and twenty-two college libraries from the Oberlin Group.4 The results are broken out for the two library types for costs, fill rate, turnaround time, and user satisfaction. A series of best practices workshops followed this study as characteristics of high-performance borrowing and lending units were identified based on costs, turnaround time, and fill rates. The last study occurred in 2002 with seventy-two participants.5 This most recent study provided an added focus on user-initiated and local document delivery services. It confirmed the success of user-initiated services and recommended moving toward that model.

Additional studies of many ILL operations that provide detailed statistics on many facets and trends of ILL include the Higher Education Interlibrary Loan Management Benchmarks study.6 The survey sample of seventy-seven libraries included community colleges as well as colleges and universities, with detailed comments from individual libraries on such issues as workflow, budgeting, distance learning, shipping, and personnel. Through detailed profiles of nine institutions’ interlibrary operations, Profiles of Best Practices in Academic Interlibrary Loan offers advice and recommendations for issues facing ILL managers in 2009.7

Managers of library services commonly ask, “What statistics should I keep and how can I evaluate our services?” As library service evaluation becomes more data-driven, it may prove even more valuable to track the volume and success of the service and ensure that the valuable work provided is recognized. Four typical methods are used to assess interlibrary services: fill rate, cost, turnaround time, and user studies. Fill rate and turnaround time are easiest to produce and document service trends more readily than user or cost studies, while user surveys might provide a richer, more contextual evaluation of the service. Although data do provide answers to questions that require counts, the context of those numbers and the trends illustrated by comparisons over time may be more important than a single point of data. It is useful to look for trends by comparing a statistic against the same statistic from a prior month or year or from the same month in the prior year. Are your numbers going up or down, and do you know why? If you are able to identify trends, you can predict future demand and determine the human and financial resources you will need for the service.

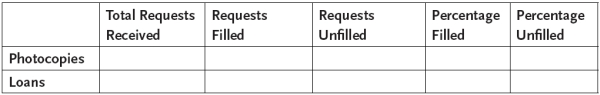

Basic statistics are generally kept monthly and compiled in an annual report. The most basic elements are requests received, requests filled, and requests not filled, perhaps separated by copies and loans, for both borrowing and lending. In any given month, however, some requests that are filled were placed the previous month. For example, a request filled in December may have been placed in November. Some management systems may report this differently, counting only the requests both made and filled in the same month.

Both borrowing and lending activities may report the same basic types of statistics as shown in table 5.2. As illustrated in table 5.3, you can adapt this report to reflect yearly totals, often broken down by month, either aggregated to include loans and photocopies or limited to just one type of request.

Table 5.2 Sample Monthly Request Activity Report

Table 5.3 Sample Yearly Compilation

Additional levels of statistics might also be warranted, such as those required by state, consortial, or reciprocal partnerships. You may want to know how much of the borrowing or lending activities are with reciprocal or in-state partners. Knowing the use both ways helps in evaluating your nonmandated reciprocal arrangements. For example, a reciprocal agreement may no longer be advantageous if you are lending considerably more than you borrow.

You may also want to track the number of different users served, which in lending would be the number of different libraries served and in borrowing might be a breakdown by user status (e.g., faculty, student, staff, graduate, undergraduate). It is often a point of pride for many interlibrary loan units to see how widely they share their collection.

Consider collecting more data than you are required to report to library administration. More details are also useful in managing the operation—for instance, tracking reasons borrowing or lending requests are unfilled. Interlibrary loan management systems allow you to manage this kind of data better, since they make tasks like finding borrowing requests that have been made but have not been received easy to do. Paper files couldn’t answer the myriad requests that our new systems make possible. Clever managers use the tools their systems provide to monitor activity.

Fill Rate

With the basic statistics you record, you can compute a fill rate. You should calculate a fill rate for both borrowing and lending activities. Also, the fill rate for articles might differ from that of loans, so it may be useful to compute them separately to get a complete picture. For example, the total fill rate alone may not show that the fill rate for articles is higher than that for loans. Knowing that discrepancy can allow you to focus on loan fulfillment strategies.

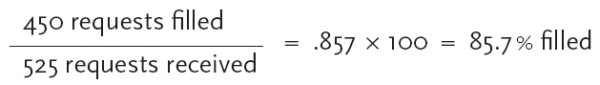

Fill rate is the ratio of requests filled to the number of requests submitted, commonly expressed as a percentage, and represents how successful you are at filling submitted requests. An example of how to calculate a fill rate follows:

Calculating a Fill Rate

Fill rate can be computed in different ways based on your interpretation of a filled request. Traditionally, the filled requests are those made through the borrowing service and supplied by another library. However, we might want to expand this definition to include requests for material found to be locally available in the library collection, including items found in licensed electronic sources or evenly freely available on the Internet. The requests you don’t need to borrow because they are available locally could be viewed as successes, too. This way, you can measure both the success of the staff in borrowing from another library as well as the success in meeting patrons’ needs in other ways. These requests reflect the workload of the office, and therefore should not diminish the fill rate by not being counted as part of the total number of filled requests. For instance, if you have a book in your own collection and your patron made an ILL request for it, you might pull the book and put it on hold for the patron. You essentially filled the request from your local collection. You might “cancel” the request and provide the patron with the call number and location of the available book. The book represents both work for the ILL department and a success for the patron, so considering it a filled request might be appropriate. Because patrons may not be able to locate the locally available items they need, and interlibrary loan staff help patrons access this material, a strong argument could be made for considering these requests successes rather than failures.

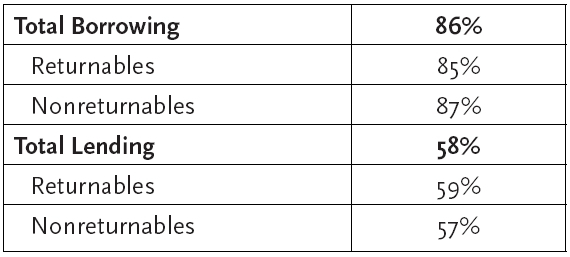

In the 2002 ARL study of ILL activity,8 one of the measures used was fill rate (see table 5.4). Although researchers used the traditional definition of “fill rate,” they recommended reaching a national consensus. The 1998 ARL study had recommended that requests for locally owned materials not be counted as filled borrowing requests.9 If you are using the traditional measure, you can compare your unit to these national averages. However, you should still capture all activity.

Table 5.4 ARL 2002 Study: Fill Rates

Source: Mary E. Jackson, Assessing ILL/DD Services: New Cost-Effective Alternatives (Washington, DC: Association of Research Libraries, 2004), 40.

In managing the activity of the borrowing unit, fill rate might not tell the whole story. For example, when a patron makes a duplicate request or requests something not yet published, should it count against the fill rate? If requests for locally available materials aren’t counted as filled requests, perhaps a new, related measure could evolve that counts the collateral work provided for patrons that doesn’t result in something borrowed. A new measure might look at the requests received but count as successes all the things the interlibrary loan unit did to meet the patron’s need: material borrowed, filled through local circulation, found freely available online, or bought on demand.

Success ratio = number of items provided to patron through the service/number of requests

This method is more oriented toward serving the customer and does not “punish” the unit for the inadequacies of the fill rate statistic. Regardless of how you calculate this statistic, it may assist you in evaluating performance but should not be the only measure used. Compute it to see where you are, then consider how you can be more effective in meeting your goals.

In lending, some libraries have a similar point of view about the inadequacies of the fill rate. If they can lend something and the borrower declines to pay the fee or is unwilling to meet a restriction, you might still consider the request a success or indicative of the work of the staff. Harry Kriz, interlibrary loan librarian emeritus at Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, makes the case that lending fill rate is not a good measure of lending staff performance.10 He argues that the factors over which his staff had little control (what the borrowers request, what is in use in the collection, and responsibility for data accuracy over which technical services has control such as maintaining serial holdings on OCLC) make lending fill rate an incomplete and inaccurate measure of lending activities. However, it can illuminate issues that, if resolved, might increase the lending unit’s productivity.

One example of this strategy is to examine the reasons you say no to incoming lending requests. OCLC WorldCat Resource Sharing libraries can examine the Reasons for No (RFN) report (see figure 3.1). It is available for download from OCLC each month. Additionally, an automated ILL system may be able to report this information. However, in order for this report to be useful, you must provide borrowing libraries with the reason you were unable to fill a request. Providing a reason for not filling a request should be a best practice, both as a courtesy to the borrowing library and for assessment of the lending unit.

To best review cancellation reasons by using the Reasons for No report, export the report to Excel for sorting and counting. You can then review the requests under each reason. Some reasons provide opportunities to improve the number of requests you fill in the future. If you review the requests you didn’t fill by each cancellation reason, you might consider changes in policies, target issues for training, or solve problems of access or bibliographic control at your institution. For example, the Not Owned reason might highlight the discrepancy between current inventory as found in the online catalog and the holdings listed for your library on OCLC. Do you have a process in place to ask cataloging to remove your symbol from an OCLC record? If staff are unable to incorporate this practice into the workflow, you might offer to perform this simple task within the ILL unit.

If the most frequent reason article requests are not being filled is Lacking Volume/Issue, this highlights an opportunity to work with the serials department to create local holdings records in OCLC WorldCat. This action may result in savings of staff time and higher fill rate. Reviewing these data on a regular basis might help solve problems in the future. In addition to the Reasons for No report, you can use the OCLC Strategic Union List report to identify the serials requested and the number filled. Another strategy is to customize the ILL management system to record separate cancellation reasons for lending article requests that need Local Holdings Records (LHR) attention and those that don’t, in order to regularly pull out the records that need LHR attention. The strategy of working with other departments in your library to improve ILL department performance is discussed later in this chapter.

Although unfilled requests for material that is in use, noncirculating, or on reserve are not failures that can be fixed, searching for lost or not-on-shelf books that might be replaced or withdrawn will improve your lending fill rate and aid your own patrons. Though many systems allow a set number of days for responding to lending requests (e.g., in OCLC it is four), it has become a best practice to say no to a request that you don’t find on the shelf after one search, rather than searching a second time for the material. By checking a list of missing items or material not found on the shelf and looking for them later, you might be able to make them available again.

People have argued that if a borrowing library refuses your conditions on an item you could have lent, it should not count as unfilled, because you were willing to lend it under the conditions specified. Check the Reasons for No report to see these requests. Libraries that regularly make requests without meeting your lending fee may not be using OCLC Custom Holdings to identify libraries by fee and should be encouraged to make better use of it or the Policies Directory because those requests are preventable from a lender’s perspective.

Cost Management

A manager should track interlibrary loan fees to be aware of any unexpected costs produced by poor workflow or choice of lenders. Tracking and reporting the amount paid by invoice in both borrowing and lending should be included in cost management processes. If you use the OCLC Interlibrary Fee Management (IFM) system, you can reconcile resource-sharing charges and receipts using the monthly reports made available at OCLC. Even a cursory review of those reports can alert you to charging errors that can be corrected or suggest libraries to pursue for reciprocal relationships.

Turnaround Time

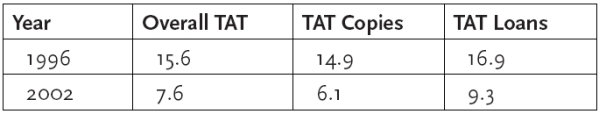

Getting materials quickly for patrons has always been a goal for interlibrary services. The dramatic decrease in turnaround time (TAT) in the past decade has helped to make ILL a service not only for the scholar working on long-term projects but for all patrons. The 1996 and 2002 ARL studies measured turnaround time and provide some baseline data for comparison with the faster times we are certain to find today (see table 5.5). As Mary Jackson noted, “Turnaround time for mediated borrowing is the one measure that has shown the greatest improvement since 1996. The overall turnaround time is 7.6 calendar days, 49 percent faster than the 1996 mean turnaround time of 15.6 calendar days.”11 Loan turnaround time was found to be on average 9.3 days, reduced from 16.9 days in the earlier study, and turnaround time for copies 6.1 days, much faster that the 14.9 days found in 1996.12

Table 5.5 Turnaround Time (TAT) in Two ARL Studies

Source: Mary E. Jackson, Measuring the Performance of Interlibrary Loan Operations in North American Research and College Libraries (Washington, DC: Association of Research Libraries, 1998).

Turnaround time should be measured from the time the user makes the request to the time the material is made available to him. Every transaction consists of several steps, and the improvements in overall turnaround time can continue by reducing the time of each step in the process. Let’s look at a model of steps in requesting in borrowing and some of the ways time can be reduced.

Steps in the Borrowing Process

- 1. Patron makes request to ILL; unmediated requesting: Direct Request, possible in Rapid

- 2. Borrowing reviews request and places request to potential lender

- 3. Lending library receives and reviews request, may say no or continue to process

- 4. Lending library processes and ships material

- 5. Borrowing library receives material

- 6. Borrowing library makes material available to patron

How can turnaround time be improved?

For step 1, web-based request forms have reduced to almost zero the time between the patron initiating the request and the borrowing unit receiving the request.

For step 2, the 2002 ARL study revealed that the range of time required to send a request to the first potential supplier was 1.0 days for fifty-eight of the libraries in the study, but only 7.2 hours at the libraries with the best turnaround time. A solution to this delay is to reduce staff mediation by moving as much mediated ILL traffic as possible to user-initiated services.

Even within traditional OCLC interlibrary loan (i.e., not direct consortial borrowing), using OCLC Direct Request allows requests to be sent to a lender in the WorldCat Resource Sharing system without mediation of borrowing staff. Direct Request uses a profile of rules that determine the criteria by which a request will be automatically sent directly to a potential lending library. It is based on the libraries in your OCLC Custom Holdings groups. You might look at Direct Request as a way of automating a portion of your loan requests and experiment with it. Because a smaller number of requests will be left to mediate, they can be handled more quickly. You can expect a reduction in overall turnaround time, even taking into account that lenders may not be working or shipping on weekends. An improved turnaround time may also result from selecting faster lenders and keeping your preferences for price, speed, and quality in your Custom Holdings groups.

For steps 3 and 4, the burden to reduce turnaround time rests on the lender. Two simple techniques that can reduce turnaround time and improve the service you provide to borrowing libraries are to download requests more frequently and to utilize OCLC deflection rules to deflect requests for material types you do not loan. Printing address labels from a database in an ILL management or shipping system and using couriers reduce the time spent processing material for shipping. See chapter 3 on lending workflow for more discussion of shipping options.

As more requests are made for journal articles that can be filled from online resources, less time is required to pull, scan, and reshelve paper journals. Electronic journals now commonly allow their content to be used to fill ILL requests, though there may be requirements such as printing of the articles and scanning a printed copy (versus sending the electronic copy). Examine your license agreements to determine your rights. Of course, the biggest improvement in turnaround time for articles has been made by the electronic transmission of article requests using Ariel, Odyssey, or e-mail or by posting the article on a web server.

For steps 5 and 6, Odyssey, ClioAdvanced, and Ariel can post articles automatically to a web server, which removes the time and delay necessary for staff to process articles when they come to the borrowing office electronically. These requests are automatically posted to the Web, and the patron is notified moments after the lending library scans and sends the article, regardless whether the ILL office is open.

You may be able to track turnaround time for specific lenders through a management system or through OCLC-provided statistics. OCLC reports the average turnaround time each month on the Borrower Activity Overview Report. This report counts by whole days from the time the request is placed on OCLC until it is updated to “filled” in the system. So although it doesn’t measure steps 1 and 6, it is a useful and consistently measured metric of performance that does allow comparison between libraries for steps 2–5.

User Studies

Another method for evaluating service is to conduct patron surveys. Libraries are turning more to users to find out what is important to them and to ensure that services meet their needs. We can ask our users directly through web survey tools. Patron satisfaction is frequently studied, as is whether a filled request was timely enough to meet the user’s needs. Conducting user surveys can be as simple as including a link to an online survey in a notification e-mail or as elaborate as soliciting users and selecting participants based on status, amount of use of the service, or other criteria.

The Higher Education Interlibrary Loan Management Benchmarks report found 15 percent of the libraries sampled had done a user survey in the past four years, but a user study doesn’t have to be just about interlibrary service.13 Some libraries that participate in the ARL LibQUAL+ surveys have added local questions specifically about interlibrary services, using that model to ascertain whether the perceived service meets the desired level of service. Because LibQUAL+ addresses library services, collections, and place, it is an example of how interlibrary services can be just one part of a larger study. User comments about services also come without prompting.

STAFFING AND HUMAN RESOURCES

There is wide variation in the ways interlibrary loan is done across libraries. It is common for libraries to have a range of employees involved in some aspect of interlibrary loan: students, paraprofessionals, and librarians. As more automation is possible, some processes and functions have really evolved, so the tasks have changed to reduce the amount of clerical processing. Filing and keying data formerly took up much more time, leaving more complex work of a higher level.

The 2002 ARL study concluded that 58 percent of the cost of borrowing and 75 percent of the lending unit costs were staff-related.14 In a large library it makes sense to have a librarian head the unit because of the level of expertise needed. A librarian can work with other units in the library as a peer, develop relationships with other libraries, reinforce the needs of ILL with library administration, and keep up with developments in the field with an eye out for new ways of doing things that will improve patron service. High-level paraprofessional staff can successfully head the unit too, because they often develop considerable expertise, particularly when they have the support and advocacy of a librarian supervisor.

Hiring and Training

What’s unique about interlibrary services in terms of developing a job description and searching for candidates? We’d like our staff to have a strong service orientation and a belief in the value of the service. An affinity for working with bibliographic information and an attention to detail are also requirements. Candidates without those qualities often are exposed in the application materials. Now, more than ever, a willingness to explore new technology and adapt to changes is also necessary. In my experience, the most important quality to look for is a cooperative spirit—can a candidate get along with people well, be flexible and willing to consider alternatives? This is a helping profession, and many of the bibliographic skills required can be learned if a person can attend to detail. When screening candidates, one useful tactic is to examine their work history for the types of skills required to be successful in the job. Food service, for example, may not seem an obvious indicator of success in interlibrary loan, but it often requires the incumbent to be able to juggle multiple orders or tables, interact with coworkers in other departments (e.g., cooks or busboys), and maintain a good rapport with customers. It is also crucial to discover why a person left such a job. If she left because she did not like the hectic nature of the work or had difficulty remembering customer orders, it may be that she is not a good fit for a job in interlibrary loan.

It is likely that unless they have been reviewed recently, interlibrary loan employees’ job descriptions should be evaluated to recognize the higher-level, more technical skills that have overtaken the highly repetitive clerical work of keying and filing. Problem-solving skills are needed for the more difficult bibliographic issues that can arise. The successful interlibrary loan employee will combine these skills with an understanding of the various systems that interact to provide interlibrary services.

Orientation and Training

Basic orientation of a new hire might start with a review of the library and ILL service website to develop familiarity with published policies. That exploration should lead to an important discussion of the services of the unit. If an ILL manual exists, introduce it as a source to consult, and demonstrate the basic tasks of the position. Show the new person what you do, talking through the steps of handling requests. This discussion also imparts the philosophy of service that you’d like to promote. If you don’t have a procedure manual, a new person might draft one to document the steps he learns. Encourage questions and note-taking.

Allowing new staff members to handle requests and demonstrate their thinking will confirm that they are on the right track. Being immediately available when unfamiliar types of issues arise allows requests to be handled swiftly. It can be useful to establish a process for referring requests that need more attention. It may also be helpful to allow a new hire to submit easier requests to build confidence while working together on harder ones. Unfilled requests will help identify areas for further training.

The print bibliographic verification tools that new borrowing staff had to become familiar with as part of their training are not as important today because better tools exist online. Now, a Google search might identify a potential lender for a request, decode a journal abbreviation, and even find the source the patron used to obtain the citation information submitted in the ILL request. Verification in traditional paper tools such as the National Union Catalog or the Union List of Serials in Libraries of the United States and Canada is needed much less. More frequently, discovering whether or not something is available freely on the Internet, such as in Google Books, is part of the search process.

Students workers can and do perform a great deal of the work in academic interlibrary loan offices. Well-trained students make a significant contribution as they place requests, process incoming material and returns in borrowing, and search, pull, scan, process, and check in returns in lending. They are essential to the team. Their orientation should include an illustration of the overall picture in order to fully understand the contribution of the office. Motivating them with rewards, merit and longevity pay increases, and recognition of special occasions helps retain them.

Staffing Options

The ARL studies found that the average number of requests handled per full-time equivalent (FTE) employee was 4,394 in borrowing and 10,297 in lending.15 The Greater Western Library Alliance (GWLA) libraries suggest a staffing guideline of one FTE for each 4,000–5,500 requests received annually for borrowing and one FTE for each 8,000–10,000 requests received annually in lending.16 Staff time is still the majority of the cost of an ILL transaction, so increasing the number of requests handled per person is a way of reducing the unit cost.

Reviewing each step of the workflow helps streamline actions to reduce the time taken in each part of the process. This reorganization often leads to changes in who does what task and how. In large public or academic libraries, a centralized ILL lending office may receive requests for items that are housed at another location. The traditional approach to this situation uses student workers or pages. These part-time workers report to the central location daily and then travel to various libraries to pick up materials to be loaned or photocopied. We referred to it as sneakernet. However, handling article requests in a decentralized library system can also be done by using staff members and students already working at remote locations in new ways. Rather than spending ten minutes of student wages to send the student to a location, it is more efficient to send the request to the library electronically. In ILLiad, this transmission can be accomplished by e-mail or other routing. This method saves time and also makes the library aware of what is needed from its collection. Local staff may know better than centralized staff how to find material that is not on the shelves and may also be better able to resolve problematic citations given their expertise in the subject.

If the requests are traveling to the distributed locations, it is also possible to install scanners in these locations so that journals do not have to travel back to the central unit for scanning. Distributing the scanning workload is a new way of working with staff in scattered locations and gives those locations new ways to bring their collections to users who are often outside the local institution. Staff and students who don’t work directly for interlibrary services may be doing more of the work. This presents a challenge for administrators who should update job descriptions to reflect the changes, develop work priorities, and contribute to staff evaluations. This type of shared responsibility can also happen within the same physical location, but with different departments participating in the process. In some libraries, circulation desk workers may engage in scanning or searching for interlibrary services, or shelving staff may be responsible for pulling requests for interlibrary loan.

In some libraries, people who do interlibrary services may hold joint positions in other units like circulation, reference, or cataloging. Because much of the interlibrary loan workflow is location-independent, it’s not surprising to see someone working on ILL requests at another service desk. Many reference desks have slow times, so working on other projects is an efficient use of staff time. Cross-department collaborations enrich our work and maximize the use of personnel, particularly when across-unit staffing allows for a greater number of hours to be covered over the course of a workday.

WORKING WITH OTHER UNITS IN THE LIBRARY

Over the years, there has been much discussion of where interlibrary services fit into the organizational structure of the library. No single best answer has emerged. In some libraries ILL might be part of reference, circulation, a larger access services unit, or even acquisitions. The service may be split into separate borrowing and lending units as well. It seems that the size of the unit, local practices, staffing, and organizational history might hold clues as to where it is placed in the organization. Keeping borrowing and lending together is desirable to take advantage of the cross-training of staff and their shared understanding of the service. Regardless of where the unit is placed administratively, it is imperative that the manager work with other units in the library to optimize the strength of human resources and to provide the best service possible.

What’s in the name, Interlibrary Loan? Because we are describing a service that may be evolving to provide requested documents rather than just borrow from another library, is it time to reconsider the name or even the service’s role in the organization? Every interlibrary loan office certainly delivers documents and borrows from other libraries too, but is there a better name than Interlibrary Loan that is immediately well recognized by users and other practitioners? We often see Interlibrary Services or Document Delivery as names to reflect the changes that have taken place. Ask yourself, when you are searching other library websites to find their service, what’s clear to you? What name would be clear to your users? Has our role now outgrown our name?

Interlibrary services impact and are impacted by many areas of the library. The services you are able to provide are based on your own collection, your users’ access to it, and the records you share. We are fortunate to be in a position to see the big picture of what our patrons need and to help solve problems when our patrons can’t access the content we have and come to us for help. We represent all other patrons from other libraries in our lending services. We may also be the most frequent user of our catalog, as we search requests for our patrons and for patrons at other libraries every day. These are some of the reasons that developing strong working relationships with other departments is so important for interlibrary services.

Let’s look at some other units in a library and consider how interlibrary services might work with them to provide the best service.

Information Technology (IT)

Given the number of systems and software ILL uses daily, ensuring that you have the support of the information technology department in the library is essential. The time-sensitive nature of interlibrary transactions requires immediate resolution of problems that arise. Because some software is unique to interlibrary services, our IT needs differ from those of the rest of the library. Even system upgrades often require careful scheduling with IT in order to provide continuity of service.

Your IT people will need to be involved in decisions about adopting new systems if they are going to be called upon to support them. As interlibrary services become more system-dependent, with more ways to customize service with APIs (application programming interfaces), widgets, and other tools, more technical skills and knowledge will be necessary to fulfill our mission.

Cataloging

An interlibrary loan unit relies on the work of cataloging because the representation of the library’s collection on WorldCat is so important for lending. The use of WorldCat as a union database of holdings for the United States, and increasingly internationally, is pervasive. We rely on WorldCat to help identify who owns a work and who doesn’t. This is true for both borrowing and lending as more people use versions of WorldCat to discover material. Although patrons using WorldCat might want to learn whether an item is owned by a library close by, they may also be likely to identify something held only in another country.

Libraries vary widely in maintaining their holdings on OCLC. Ideally, there would be a one-to-one mapping of holdings on WorldCat with the local catalog, so that WorldCat records having your library symbol are in your catalog and vice versa and so that your symbol isn’t attached to records you don’t own. Whenever a person identifies a record on WorldCat with your symbol, it should be an accurate display of ownership. Increasingly, patrons are using that database as a union catalog for all libraries. This is particularly true for WorldCat Local libraries. Different versions of the database do have different functions. In FirstSearch WorldCat, users can launch a search of the local catalog to find local locations and confirm availability.

For lending, having a process for handling missing or lost material so that a symbol is removed from WorldCat helps reduce requests for which the Reason for No is “not owned” or “missing.” “Not owned” is a preventable reason for no, unlike “in use” or “not on shelf.” It is important to work with circulation and cataloging to achieve efficient symbol removal for discarded items.17

There is much to learn about MARC tags and fields that can help us understand records. Having a colleague in cataloging whom you can ask for help when you don’t understand some detail on a bibliographic record is a wonderful support. Such cooperation builds your knowledge and helps to solve the immediate question.

Although cataloging creates records for your local catalog, placing your library symbol on a record allows users elsewhere to find material in the collection. Because cataloging processes vary, work with cataloging staff to learn how they set the library’s symbol on records for new materials. Some libraries add their symbol to OCLC when material is ordered, so interlibrary lending might begin receiving requests immediately. We often see many symbols on OCLC records long before the work is even published, and our patrons tell us that dozens of libraries already have the item. However, in searching those local catalogs we see the items are all order records. For libraries that use WorldCat Cataloging Partners, the setting of holdings for a library symbol can be delayed 1 to 180 days to allow enough time for the material to be received, processed, and made available, which would reduce lending requests for items not yet in the collection. This is an ideal solution to reduce requests for material on order, in process, or otherwise considered not owned.

One new function that OCLC has implemented is the ability of lending libraries to deflect requests in two different ways. In the Policies Directory, a lender can easily set up a deflection so that it receives no requests for materials in a particular format, typically e-journals, e-books, media, or loans for serials. But it is also possible to deflect based on maxcost, age of material, or consortial membership. There is even a deflection for all but the “last in the lender string” so that you might only get requests that are unique at your institution or that have been through others first. It takes only a moment to set up deflections in the OCLC Policies Directory, and it is a very powerful tool to reduce requests you would not be able to fill. The requests that are deflected are reported each month as part of the Reasons for No report where the reason will be Auto Deflection, and each type is listed separately. If you’ve set up deflections, check your Reasons for No report to make sure it’s doing what you intended.

The other type of deflection can be added by coding an individual OCLC record with a Local Holdings Record (LHR) to indicate whether a work is requestable as a loan or as a photocopy. LHRs for individual items take some training to create, but deflection can be achieved by adding a code to subtag 20 or 21 of a MARC 008 field to indicate whether loan or photocopy requests will be deflected. Given the work necessary to create an LHR on an individual record, it might be best as a technique for things that will never, rather than temporarily, be lent (e.g., special collections or genealogy materials). LHRs can be batchloaded, too, so you might investigate at the OCLC website and talk with your cataloging department about the potential of LHR deflection.

Collection Development

Providing information to collection development specialists about what is borrowed or lent can reinforce the role of interlibrary services in the organization. Providing information to subject librarians on what is borrowed can increase their awareness of patrons’ interests and inform future buying decisions or result in ordering works borrowed repeatedly. Lists of titles and other reports can be generated from an interlibrary loan system or OCLC report, and the interlibrary loan office can also set up systems for subject specialists to see or create their own reports.

The OCLC Management Statistics report that is produced each month reflects each OCLC request and contains fields like call numbers, date of publication, and language that can be used in our work with collection managers. For example, in my library, we report to our Asian language bibliographers our borrowing and lending statistics for Chinese-, Japanese-, and Korean-language materials based on data from the OCLC Management Statistics report, which they in turn submit to the Council on East Asian Libraries.

Libraries using ILLiad may allow collection managers to access ILLiad’s web reports to see the amount of borrowing by department and patron status. It is also common to provide reports from customized queries for subject specialists based on a number of criteria, including books or journal titles requested multiple times. Of course, reporting materials lost in ILL transactions is another way we can work with collection managers, so that replacement can be considered.

There is a body of literature on using interlibrary loan data for collection development that suggests reviewing the frequently requested serials titles as candidates for purchase rather than continued borrowing. Many factors affect the access versus ownership issue, such as monetary costs, patron convenience, and ILL staff time. In many cases, however, the costs of borrowing and copyright fees together are often far less than the cost of a subscription. After canceling a serial, the number of ILL requests for the title can be used to confirm whether the cancellation was appropriate. As article borrowing becomes faster, particularly for libraries participating in RapidILL where fast turnaround is a requirement of participation, and as more purchase options become available from either publishers or commercial document delivery services, there are more choices to explore in support of user needs.

Subject specialists are also an asset when a second eye is necessary for both bibliographic and sourcing issues, helping us find ways to fill difficult requests. It is valuable to be able to call on the language skills of library staff, and their expertise often adds value to the transaction and enhances our professional development. Certainly, being able to refer a patron to a librarian with subject expertise for more help or who can take the time to track down the really obscure reference or provide needed instruction enhances the relationships between and among librarians and patrons.

Because collection managers often determine circulation policies, working with them on reducing restrictions imposed on lending helps make it easier to borrow more freely. Providing ILL statistics to collection managers will help them understand that in order to borrow material from other libraries, it is only fair to lend, too. Our patrons want to borrow dissertations, media, or newspapers on microfilm, so we want collection managers to allow us to lend those materials, too.

Reference and Circulation

The individuals working the information, circulation, and reference desks market interlibrary services in their work with patrons at the point-of-need. They are on the front line, assisting users with the catalog, databases, and tools that may result in interlibrary borrowing requests. Frontline staff often help patrons sign up for ILL services and educate them on procedures for placing requests. By helping users explore their options for obtaining material, these staff members are partners with interlibrary services. Ensuring that public services staff have correct information on interlibrary policies, basic procedures, and realistic turnaround times for articles and loans helps them accurately offer the service as one of the solutions to meet patron needs.

Your public services staff members also help the patrons of other libraries. As services such as Ask-A-Librarian become more widely available and used, inquiries about “How do I get…?” can also come from users outside the institution. Service desk staffers should be trained in how to answer these questions from externally affiliated patrons, as they may later result in a lending request.

Circulation departments also assist interlibrary service units by keeping material shelved accurately and by having strong processes in place for handling materials that are missing. Ensuring that the catalog reflects a missing item’s status and searching for missing materials benefit all patrons but are especially important to ILL. Many borrowing units by policy will not borrow something owned by the library until it is declared missing in the catalog, so the work of circulation helps our staff, our patrons, and the lending unit as well. Searching regularly for missing material so that it is eventually withdrawn and the symbol removed on OCLC contributes to greater success in lending.

Serials and Electronic Resources

The units that manage journal subscriptions and electronic resources are emerging as important areas for intra-library cooperation, as e-journals have become pervasive in the past decade. The primary question for ILL staff is whether they can lend an article from an electronic journal or database and, if so, with what restrictions? It is essential to work with staff in charge of the licenses to learn these details. It’s not just a matter of ascertaining what library has a serial because a library might have access for its own patrons but not have the right to lend the item to other libraries. This scenario is very different from the print world, in which copyright law allows lending. Complicating matters is that although paper and electronic journals may have different ISSNs, databases may use either of them, so requests generated from databases via OpenURL could include either ISSN.

It is common for ILL borrowing offices to still be using OCLC records for paper serials to place requests, although e-journal records for the same content may exist. There are several reasons for this. Many OCLC libraries simply have “deflected” requests for all e-journal records, so that the request never even gets reviewed by the lending library. Other libraries may choose not to fill e-journal requests if they don’t know whether they can lend a title. It may also be unclear from the electronic journal record just what years are available electronically. Although we often see online journals starting in the mid-1990s, many publishers also license backfiles. Even if the lending library has a way to know what it can and can’t lend, having that information at the point of need for the interlibrary loan unit to make a quick decision on a specific lending request may prove difficult.

As we move toward unmediated article borrowing, we may want to move to preferring records for e-journals so that lenders who have the rights to lend from electronic content can do so quickly and don’t have to scan for each request. If an article is available electronically, wouldn’t a borrower prefer to get it from a library that can fill it from an e-journal quickly rather than having to find a volume on the shelves and scan it? Having ready access to license rights information will be important in order to make progress in this area.

Even with paper serials, providing accurate information on specific holdings can reduce work for ILL staff. Using Local Holdings Records (LHRs) on OCLC, libraries are now able to indicate their specific serial holdings in addition to indicating ownership. At one time, these data were used for printed lists of serials holdings (e.g., a union list of serials held in a region or by a group). Now, OCLC libraries easily see the specific holdings of libraries in order to target their requests to libraries that own the years or volumes sought. Having accurate serials holdings records allows potential borrowing libraries to make more informed requests based on what volumes or years you own. A best practice for borrowing is to send requests only to libraries that have the needed volume. Libraries that don’t indicate their holdings may get fewer requests, while those libraries that do “union list” or create LHRs may get more requests or may reduce the number of requests for issues they do not own. OCLC provides a service for batchloading holdings information, which is now possible for books as well as serials. Libraries can also create or maintain LHRs online through the Connexion browser. Creating LHRs is only part of the workload. Maintaining them for canceled serials requires an ongoing commitment.

It is possible for the ILL office to take on some of the workload of creating and maintaining LHRs, because it is interlibrary loan lending that reaps much of the benefit by reducing the number of requests that can’t be filled. For example, Ohio State University increased its lending fill rate for articles almost 20 percent through creating LHRs.18 OCLC also reported from a pilot project in 2000 in which ILL staff created holdings records that there was an immediate 3–33 percent increase in fill rate—the more records created, the higher the fill rate.19

Special Collections

We often hear that the future of libraries will be in their special collections: the unique items collected by the library that provide depth and reflect local interests. Working with special collections can be a way for this unit to have its materials more widely used than visits to the collections allow. The Association of College and Research Libraries (ACRL) developed Guidelines for the Interlibrary Loan of Rare and Unique Materials to encourage loans while safeguarding the materials.20 The guidelines outline the responsibilities of both borrowers and lenders and call for involving the curator with requests on a case-by-case basis. This challenges us to consider working with special collections materials in an interlibrary loan process.

Digitizing on demand might also be a service in which special collections and interlibrary loan could cooperate. Some libraries, like that of the University of Michigan, are already taking lending requests for materials in the public domain and digitizing them, charging the borrowing library for the digitization work but then making it freely available.21 A review of lending requests might identify special collections materials that other scholars need and help start the conversation about working together.

Acquisitions

In many ways, our work parallels that of acquisitions, as we both take requests for material and find sources to obtain it. Purchase-on-demand programs have provided another way for acquisitions and interlibrary loan to work together. See the section “Purchase versus Borrow” in chapter 2 for a complete description of the way that ILL interacts with and makes decisions in relation to acquisitions.

CONCLUSION

Managing interlibrary services offers a wonderful, broad perspective of the interrelationship between library units. It also offers a unique chance to rethink traditional services with an orientation toward the user, to implement new technologies, and to meet users’ needs in new ways. Interlibrary service is a core service that is continually strengthened through change and gives us all the opportunity to learn every day. That’s why it is such a fulfilling aspect of librarianship.

NOTES

1. Interlibrary Loan Committee, Reference and User Services Association (RUSA), Interlibrary Loan Code for the United States, revised 2008, by the Sharing and Transforming Access to Resources Section (STARS), www.ala.org/ala/mgrps/divs/rusa/resources/guidelines/interlibrary.cfm.

2. Lee Andrew Hilyer, Interlibrary Loan and Document Delivery: Best Practices for Operating and Managing Interlibrary Loan Services in All Libraries. New York: Haworth Information Press, 2006. Published simultaneously as Lee Andrew Hilyer, “Interlibrary Loan and Document Delivery: Best Practices for Operating and Managing Interlibrary Loan Services in All Libraries; Borrowing,” Journal of Interlibrary Loan, Document Delivery and Electronic Reserve 16, no. 1–2 (2006): 8–9.

3. Marilyn M. Roche, ARL/RLG Interlibrary Loan Cost Study: A Joint Effort by the Association of Research Libraries and the Research Libraries Group (Washington, DC: Association of Research Libraries, 1993).

4. Mary E. Jackson, Measuring the Performance of Interlibrary Loan Operations in North American Research and College Libraries (Washington, DC: Association of Research Libraries, 1998).

5. Mary E. Jackson, Assessing ILL/DD Services: New Cost-Effective Alternatives (Washington, DC: Association of Research Libraries, 2004).

6. Elaine Sanchez, ed., Higher Education Interlibrary Loan Management Benchmarks, 2009–2010 ed. (New York: Primary Research Group, 2009).

7. Paul Kelsey, Profiles of Best Practices in Academic Library Interlibrary Loan (New York: Primary Research Group, 2009).

8. Jackson, Assessing ILL/DD Services, 41.

9. Jackson, Measuring the Performance of Interlibrary Loan Operations, 22.

10. Increasing Lending Fill Rates, www.ill.vt.edu/ILLiadReports/StatEssays/Increasing_Lending_Fill_Rates.htm.

11. Jackson, Assessing ILL/DD Services, 52.

12. Jackson, Measuring the Performance of Interlibrary Loan Operations.

13. Sanchez, Higher Education Interlibrary Loan Management Benchmarks, 30.

14. Jackson, Assessing ILL/DD Services, 31.

15. Ibid., 77.

16. Lars E. Leon et al., “Enhanced Resource Sharing through Group Interlibrary Loan Best Practices: A Conceptual, Structural, and Procedural Approach,” Portal: Libraries and the Academy 3, no. 3 (2003): 425.

17. Anne K. Beaubien, ARL White Paper on Interlibrary Loan (Washington, DC: Association of Research Libraries, 2007), 79.

18. Ibid., 71–72.

19. Cathy Kellum, “A Little ‘SOUL’ Increases ILL Fill Rates,” OCLC Newsletter, no. 248 (2000): 33.

20. Guidelines for the Interlibrary Loan of Rare and Unique Materials, www.ala.org/ala/mgrps/divs/acrl/standards/rareguidelines.cfm.

21. Rethinking Resource Sharing, http://rethinkingresourcesharing.org/preconf08/perrywillett_scandemand.ppt.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

American Library Association. Guidelines for the Development and Implementation of Policies, Regulations and Procedures Affecting Access to Library Materials, Services and Facilities. 2005. www.ala.org/Template.cfm?Section=otherpolicies&Template=/ContentManagement/ContentDisplay.cfm&ContentID=13141.

Association of Research Libraries. ARL Statistics 2006–2007. Washington, DC: Association of Research Libraries, 2008.

Beaubien, Anne K. ARL White Paper on Interlibrary Loan. Washington, DC: Association of Research Libraries, 2007.

Boucher, Virginia. Interlibrary Loan Practices Handbook. Chicago: American Library Association, 1984.

———. Interlibrary Loan Practices Handbook. 2nd ed. Chicago: American Library Association, 1997.

Hilyer, Lee Andrew. Interlibrary Loan and Document Delivery: Best Practices for Operating and Managing Interlibrary Loan Services in All Libraries. New York: Haworth Information Press, 2006. Published simultaneously as Lee Andrew Hilyer, “Interlibrary Loan and Document Delivery: Best Practices for Operating and Managing Interlibrary Loan Services in All Libraries; Borrowing,” Journal of Interlibrary Loan, Document Delivery and Electronic Reserve 16, no. 1–2 (2006).

Interlibrary Loan Committee, Reference and User Services Association (RUSA). Interlibrary Loan Code for the United States. Revised 2008, by the Sharing and Transforming Access to Resources Section (STARS). www.ala.org/ala/mgrps/divs/rusa/resources/guidelines/interlibrary.cfm.

Jackson, Mary E. Assessing ILL/DD Services: New Cost-Effective Alternatives. Washington, DC: Association of Research Libraries, 2004.

———. Measuring the Performance of Interlibrary Loan Operations in North American Research and College Libraries. Washington, DC: Association of Research Libraries, 1998.

Kellum, Cathy. “A Little ‘SOUL’ Increases ILL Fill Rates.” OCLC Newsletter, no. 248 (2000): 33.

Kelsey, Paul. Profiles of Best Practices in Academic Library Interlibrary Loan. New York: Primary Research Group, 2009.

Leon, Lars E., et al. “Enhanced Resource Sharing through Group Interlibrary Loan Best Practices: A Conceptual, Structural, and Procedural Approach.” Portal: Libraries and the Academy 3, no. 3 (2003): 419–30.

Matthews, Joseph R. The Evaluation and Measurement of Library Services. Westport, CT: Libraries Unlimited, 2007.