THE FUTURE OF INTERLIBRARY LOAN

Cyril Oberlander

Today there are over 11 million articles and loans moving through resource-sharing library networks each year. Cooperative cataloging, discovery tools, and the maturity of automation in request management for libraries sharing resources have significantly helped users access information and helped libraries reduce operating costs. In the past, ILL requests would be filled in two to four weeks. Now, article requests can be filled in twenty-four to forty-eight hours, and loans within three to six days. Interlibrary loan (ILL) is so successful that authors praise their ILL departments and staff in their acknowledgments; in fact, it is user output, in terms of their reading, learning, research and development, and scholarship, that is an ideal measurement of ILL’s success. Through automation, innovation, and cooperation, ILL achieved dramatic decreases in turnaround time while managing dramatic increases in borrowing and lending requests. Perhaps the best illustration of these increases is found in the 2008 Association of Research Libraries (ARL) report that shows the percentage change since 1986: borrowing up 295 percent, lending up 126 percent.1

One of ILL’s least understood successes is its effective evolution of service and technology within a cooperative framework. Arguably, the key to this success is that ILL must network well to function. In other words, performance is tied directly to the effectiveness of the lending operation of other libraries. Although libraries often place more importance on their borrowing operation because local user satisfaction is essential and immediate, a peculiar dichotomy or shared balance exists with serving internal and external users. For example, the increased use of unmediated borrowing processing has resulted in increased citation verification by the lending libraries. ILL’s role has always been multifaceted, with one foot in the local library and the other foot in other institutions and consortia. Similarly, because ILL’s broad service dimension includes providing some reference and technical service, ILL units have a history of constant organizational change produced by shifts in reporting to different units: access, technical, and reference services.

ILL services are a practical and strategic way libraries cooperate, and that cooperation is reinforced by the shared problem solving required to locate and obtain information for users within various networks. Through such problem solving, ILL practitioners have shaped today’s ILL processes by migrating from printed national union catalogs to online bibliographic catalogs and from paper requests to OpenURL requests. Tomorrow’s ILL will incorporate new services that strategically resolve user needs with robust information supply options. The commercialization of content that has coincided with the phenomenal growth in free open access content has created an Internet-based supply of information that increases the complexity and variation in ILL workflow. Information supply has exponentially expanded beyond library models, and as a result, our users expect more service options. We are at a tipping point for traditional ILL at the peak of its success. To incorporate these emergent supply chains, the new ILL systems must query many external systems and weave the outputs into a shared decision-making framework that creates innovative ways to connect users with information and transforms library services and workflows.

As the information landscape continues to be reshaped by emerging distribution and publishing systems and maturing digitization programs, the strategy best suited for the future of ILL services should remain focused on the user and his request. However, in order to provide more effective service, continued commitment to workflow optimization within networks of resource-sharing partners is not enough; I predict that our future depends on our experimenting with how ILL functions—in particular, developing new internal partnerships within the library (e.g., acquisitions/collection development, digital library production, etc.) and developing workflows with external linkages such as publishers’ pay-per-view websites, vendor web services, and a host of free and sharing services available from the Internet.

INFORMATION SUPPLY—FEE-BASED PARTNERS

Purchasing options are increasingly less expensive and faster than traditional ILL, especially if there are copyright royalty fees or lending charges. In 2009, for example, the copyright royalty for Agriculture and Human Values was $33.00, while the cost to buy an article directly from the publisher was $9.64. Similarly, the royalty fee for Journal of Health Psychology was $26.00, while pay-per-view was only $15.00. Pay-per-view expanded as publishers increased their discovery via search engines and adopted direct sales of articles via the Internet. This growth will continue as the Internet publishing marketplace for end-user services matures. This development means that for ILL, article purchase is often less expensive than copyright royalty fees combined with lending charges, while providing high-quality color articles faster than borrowing black-and-white articles. ILL systems should incorporate this new reality into their processes and workflow and streamline the determination of when and how to purchase articles using credit cards, EDI (Electronic Data Interchange), IFM, tokens, and the like.

Just-in-time acquisitions or purchase-on-demand for monographs is already a viable alternative to interlibrary loan.2 For example, in 2007–2008, SUNY Geneseo’s ILL placed three borrowing requests for The Boyhood Diary of Theodore Roosevelt, 1869–1870: Early Travels of the 26th U.S. President, paying a total of $30.00 in lending charges. Meanwhile, used copies were available from Amazon for $2.36. As purchasing books is seriously competing with the cost of borrowing them from libraries, the opportunity to change ILL practice coincides with libraries shifting from just-in-case acquisition models toward just-in-time and user-initiated models. Today’s latest e-book license models are designed with various purchase-on-demand strategies; however, selecting physical collections largely remains vendor and librarian driven. Now it is rare that books are unavailable in the marketplace because so many options exist for buying new or used items (many a result of library weeding) as well as digital and physical reprints. Digital and reprint print-on-demand industries are helping ILL obtain rare materials that are inaccessible through borrowing. Given this marketplace reality, when to buy and when to borrow becomes an opportunity for strategic convergence among ILL, acquisitions, and collection development. For example, SUNY Geneseo twice borrowed Ethnic Conflict in Sri Lanka: Changing Dynamics for a total of $40.00 in lending charges. That title was available for purchase for only $9.99 and was held by only twenty-two libraries in WorldCat. Geneseo twice missed the opportunity to buy a work needed by users. Purchasing would have diversified the collection held within the network. ILL is in a unique position to facilitate a conversation with users, using data such as cost, uniqueness, and user needs, and with various library stakeholders such as acquisitions and collection development. From these conversations we can develop strategies that help us achieve long-held but rarely achieved cooperative collection development goals.

There are other information suppliers in this marketplace of interest—they are the hybrid fee-based suppliers emerging as resources that can be incorporated into the ILL workflow. These new players include content rental services such as Net-flix (www.netflix.com) and McNaughton Books (www.mcnaughtonbooks.com) and peer-to-peer sharing services such as BookMooch (http://bookmooch.com) and PaperBackSwap (www.paperbackswap.com). Increasingly, libraries will use these services to fill certain niche needs that are not easily served by sharing library collections or purchasing for the collection.

INFORMATION SUPPLY—FREE SUPPLIERS AS PARTNERS

Freely available full text on the Internet is increasingly filling ILL requests and proving a fast and inexpensive source compared to obtaining articles from traditional borrowing processing.3 Increasingly, ILL staff are using a search engine to find articles on the open Web before submitting a borrowing request. In 2009, ILL units at two libraries using search engines as their first step in the bibliographic searching process reported 5 percent and 6 percent cancellation rates of their article requests because they found the full-text article on the open Web. By 2012, free full text on the Web may fill 20 percent of ILL requests. At various ILL conferences, I ask audience members if they use a search engine to verify citations. Most attendees report using search engines as their first bibliographic verification tool of choice. As a result of using that tool, many ILL units are canceling requests when they find full text and are sending their user the URL to the information resource. Ironically, canceling a “filled” ILL request by supplying the URL to free full text doesn’t traditionally count in ILL’s fill statistics, and this fact reinforces ILL as exclusively a library-to-library operation. Increasingly, ILL staff are changing how they count filled requests because the outcome is based on the user’s perspective, not the supply method or source. As more libraries embrace this definition of a filled request, the workflow and ILL management systems will follow the evolving practice and better integrate search engines and Internet suppliers into existing workflows.

Because free full-text articles and books are increasingly available and found using search engines, the real challenge for ILL practitioners is to resolve the disparate and confusing sources, some with free and some with pay-per-view options. Following are some of the important sources of free full text:

• arXiv (580,000 e-prints), http://arxiv.org

• Directory of Open Access Journals (5,513 journals; 459,876 articles), www.doaj.org

• Electronic Theses Online Service (250,000+ theses), www.ethos.ac.uk

• E-PRINT Network (5.5 million e-prints), www.osti.gov/eprints/

• Google Books (millions of full-view books), http://books.google.com

• HathiTrust (5.2 million volumes), www.hathitrust.org

• Networked Digital Library of Theses and Dissertations (793,000 works), www.ndltd.org

• Open Content Alliance, volumes available at www.archive.org/details/texts/

• OpenDOAR (1,650 repositories), www.opendoar.org

• Project Gutenberg (30,000 books), www.gutenberg.org

• Web archiving:

• Internet Archive (150 billion pages), www.archive.org

• Internet Archive’s Text Archive (1.8 million works), www.archive.org/details/texts/

• Pandora, Australia’s web archive, http://pandora.nla.gov.au

• UK Web Archive (127.9 million files), www.webarchive.org.uk/ukwa/info/about/

Looking more specifically at Google Books, a 2006 study of ILL requests at the University of Virginia found 2.6 percent of pre-1923 ILL loan requests could have been filled by Google Books. The following year that percentage grew to 23 percent.4 The Google Books settlement and the establishment of subscription models for Google Editions further promise to alter the ILL workflow by introducing new opportunities for purchasing content.

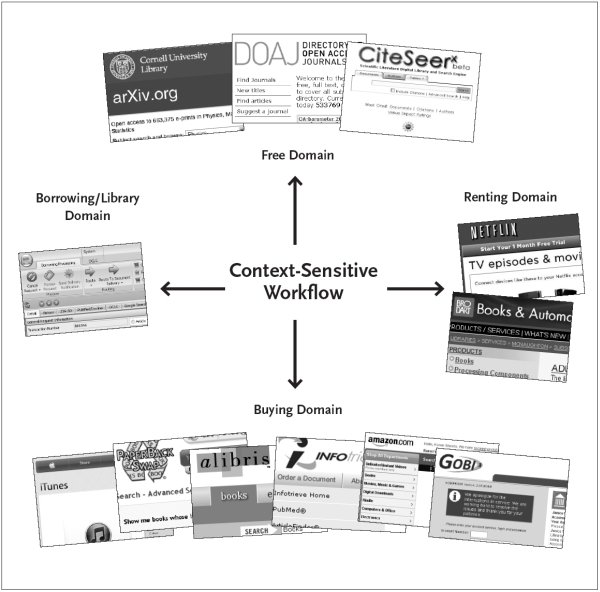

ILL’s information supply reality is so rich with options that our challenge ahead is creating flexible and quick integration of new sources into ILL and user workflow while thoughtfully balancing automation with cost (time, budget, complexity/noise, scalability, stability). The rapidly evolving landscape may be broadly defined as having four dynamic dimensions (see figure 7.1):

- A free domain that includes the plethora of open access repositories, author websites, digital libraries, mass digitization sites, and publisher and online distributor sites

- A buying domain that includes various online and physical marketplaces where users or ILL purchase books from book sellers, articles from publishers or distributors, music and video from various online services, and so on

- A renting domain with emerging service models that fill niche demands that are problematic for ILL services; libraries may lease collections of popular titles and textbooks through a McNaughton plan or supplement their ILL services for videos by renting titles from services such as Netflix

- A borrowing domain, best described in the chapter on borrowing; however, paying lending charges resembles the renting domain

Figure 7.1 Decision and Sense Making in the User and Library Workflow

SENSE-MAKING AND INFORMED DECISION WORKFLOW

User adoption of various web services in the free, buying, and renting domains can help us to make sense of or resolve this cornucopia of options. ILL request processing is increasingly developing new context-sensitive workflow that incorporates web searching, often for verification, and purchasing options, often for new books. Most recently, the addition of Addons to ILLiad allows library staff to integrate web services within the ILLiad Client.5 OpenURL resolvers, OCLC cataloging, book vendors, and search engines are already available.

Together, users and ILL staff will strategically navigate these similar landscapes of information supply to produce innovative strategies that improve mutual informed decision making and expand service. Tools that automate and resolve data help us streamline and bundle options. Book Burro (www.bookburro.org) was an early tool that developed automatic resolution of information supply for end users. This Firefox extension provides quick access to numerous options for book readers, including libraries holding the work by location, price to purchase, peer-to-peer sharing, and other service options. Practically speaking, an end user could easily take a desired book record and choose a delivery option by comparing the display of the nearest library holding that item with the cost of buying it from various vendors or obtaining it for free using peer-sharing networks. Bundling and comparing services will increasingly be configurable by both end users and libraries.

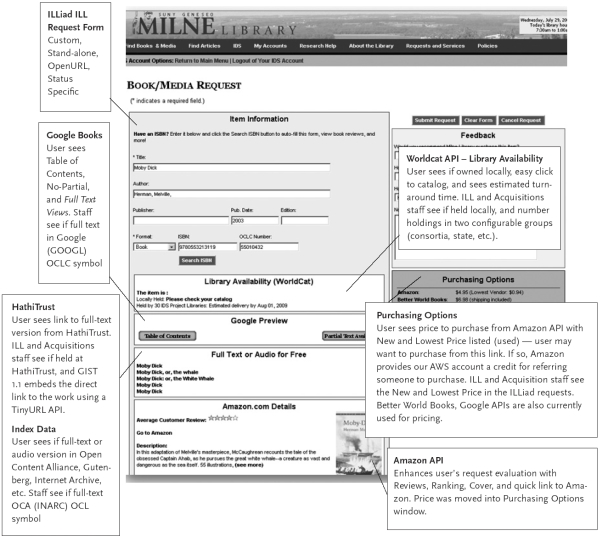

The Getting It System Toolkit, or GIST (http://idsproject.org/Tools/GIST.aspx), is an example of a hybrid ILL workflow, originally developed for ILLiad systems, and is configured to resolve and utilize various information supply options for both end users and library staff. GIST creates opportunities for acquisitions and ILL to share a request management platform that is flexible enough to allow for local practices and powerful enough to simplify and expand traditional acquisitions and ILL. The screenshot in figure 7.2 shows the GIST request form—a customized ILL request form—with information labels added to describe the customizable data feeds from various API sources. GIST web interface widgets include the following:

- The WorldCat API provides users a link to local holdings and estimates delivery time based on the customizable OCLC Holdings groups. Holdings data are used by the staff and ILLiad workflow to provide automated routing based on holdings and collection-building criteria for diversifying holdings in acquisition decisions.

- The Google Books, Index Data, and HathiTrust APIs provide users with a variety of preview and full-text linking options, while also providing ILL workflow options to automate routing and easily fill requests with full-text links.

- The Amazon API enhances the user’s evaluation of the work by adding reviews data and a book cover. It also provides users with a link to a purchasing option and adds the new and lowest-cost prices. With Amazon’s API, ILL staff can easily compare the cost of purchasing with the cost of lending charges.

Figure 7.2 Getting It System Toolkit: A Hybrid Discovery-Delivery User Interface

GIST is an example of how ILL tools will incorporate a variety of information supply options from the nonborrowing domains into both the user and staff interfaces. This merging empowers both the user and the staff to meet their goals and allows both to make informed and faster choices about the request.

Amassing useful data and building them into user and ILL workflows is an essential part of the future of ILL. Gathering data such as previews, reviews, and user ratings enhances the user’s information discovery and request experience and attempts to answer the problem posed by Danuta Nitecki in 1984: “We are still faced with insufficient techniques for accurately identifying actual user needs and delivering the specific information required. Often an identified citation is a hoped-for solution. After waiting for its delivery and examining it, the user may find it to be inadequate and so must begin the search anew.”6

THE FUTURE OF ILL AND ELECTRONIC BOOKS

Two important activities for which resource-sharing systems must develop solutions are lending electronic books and enhancing delivery service options. E-book platforms and format preferences challenge libraries with a cornucopia of confusing options and noninteroperable systems; worse yet, e-books are a significant challenge to resource sharing because few subscription licenses allow for lending. In addition, for those few e-books with ILL rights allowed, the current practice of file sharing chapters is neither a scalable nor long-term solution. Readers will ultimately define the winners or create their own solutions. Future ILL systems and workflow will behave more like digital rights management software and provide a new digital object authentication framework to provide seamless and temporary access to particular titles. In fact, combining this framework with OCLC Direct Request and other unmediated borrowing request systems would result in unmediated lending.

DELIVERY, DELIVERY, DELIVERY—THE FUTURE OF EXPANDING ILL SERVICES

ILL values getting users what they want at a title or edition level, but we rarely ask users how they want that work delivered (i.e., to home or another location or in a specific format). The richness of information tools and the supply domain is helping to shape user expectations about content and delivery and is encouraging us to rethink delivery problems. Although many users want to visit the library to pick up their books, others would rather we send materials directly to their home, office, or desktop. Sensitive to cost, libraries often choose to limit service models at the cost of user preference; this restriction is obvious in the case of mandating electronic delivery for articles in order to reduce the cost of printing, but less obvious in the case of home delivery.

Home delivery of physical books has a long history and will become a reality again. Though many are familiar with bookmobiles, few know that in 1935, during the Great Depression, Kentucky’s Pack Horse Library Project was established as one of the Works Progress Administration’s programs in eastern Kentucky.7 To provide reading materials to rural communities of eastern Kentucky, librarians would ride horses or mules, walk, or even row boats to deliver books and magazines to homes. By 1939, the thirty Packhorse “libraries” served over 48,000 families—almost 181,000 individuals—with 889,694 book circulations (amazing considering that they only had 154,846 books available) and 1,095,410 magazine circulations (again amazing—they only had 229,778 magazines).8 Past efforts such as these help us realize what our users want and what we are capable of.

Today, the growth of remote user or distance education library services has increased the need for home or office delivery services. The current library-to-library model of interlibrary loan necessitates four shipments per transaction: from lending library to borrowing library, from borrowing library to remote patron and back again, then finally back to the lending library. Options for direct delivery to users will expand in the next few years. If we can reduce the number of shipments involved, libraries can provide faster service to users at lower costs. One of the critical delivery options for the future of ILL is to act as a reformatting service to convert legacy print collections to digital. More libraries are scanning and delivering their print resources because print has replaced microform as the inconvenient format of the twenty-first century. One of the earliest leaders in this hybridization of ILL as document delivery service was Zheng Ye Yang and Texas A&M University Libraries. In June 2002, Texas A&M significantly expanded its services to digitize or reformat its print collections on demand by implementing free electronic document delivery of articles for a campus of 48,000 students. Increasingly, ILL personnel will change ILL services and systems to include more document delivery, digital library production, digitization on demand that supports print-on-demand or reprinting services, and other services such as Optical Character Recognition (OCR). The need for format conversion parallels users’ expectations that the content we deliver take the form of their preferred technology and intended use.

CHANGE FACTORS FOR TOMORROW’S HYBRID SERVICES AND CONTEXT-SENSITIVE WORKFLOW

Today’s workflow must evolve new service models because of several key factors in our environment:

- Increased full-text sources will reduce the need for scanning of print.

- Decreased monograph purchasing will necessitate expanding cooperative networks that reduce cost.

- Increased weeding of collections will reinforce the need to expand cooperative collection development and resource-sharing networks and to create last-copy titles with noncirculating or nonlending status.

- Continued maturity of free and fee-based information suppliers will change not only ILL workflow but also the name of ILL service.

As information supply continues to expand options, the variety of information supply channels and demands encourages us to make strategic choices. Making those choices transparent and context sensitive for users and libraries helps all of us make informed decisions. Systems and strategies that bundle data and services in new, flexible, and streamlined ways that help users and library staff achieve their goals will provide a new service framework for libraries. Some current strategies aren’t viable in the long term. For example, lending libraries that rely on income from fees will increasingly face challenges because they compete in a market offering better prices and better services (e.g., purchasing eliminates the need for due dates) from book and article distributors. The implication for libraries is that some of the ILL workflow can be reduced or eliminated, while other components can be transformed into new service models. For example, the benefits of merging ILL and acquisitions workflow are now more technically and economically viable because the resources, strategies, and tools are mature enough to make migration to a new service unit possible. Requests become the vehicles to disambiguate library service around the context of user, information, and library service. If a user is placing a book request, the possible activities related to that request may include but are not limited to the following:

- Picking the book up at the desk to read it

- Receiving the book at home to read it

- Accessing the book via laptop as a PDF, a WAV, or an MP3 or via a portable reader of his or her choice

- Sharing the book on course reserves, in group projects or reading groups, with librarians or instructors for discussion, or in social online collaboration tools

- Integrating the book into adaptive learning software, bibliographic management software, or a course management system.

The future of ILL is rich with possible resolution of data and service options that support mutual goals and strategies. For example, the future authors of digital projects and scholarship will require a hybrid of supporting services that foster long-term relationships with authors, researchers, communities, projects, and the like. In that environment, the role of ILL librarian as consultant can grow, and the value of ILL services will be significantly expanded. Group projects that require collections, space, and project support will utilize more sophisticated request management tools. Library consultation services such as these will change the nature of ILL and reference. Reserve and ILL will see more opportunities to develop schedulable on-demand collections that combine library collections and borrowed collections (libraries, faculty personal copies, etc.) with curriculum and instruction. Increasingly, the request management services of libraries will have more in common with customer relations management software because sense making with the user in mind means leveraging strengths of resources and services, and that makes each service request an opportunity to reinforce mutually supportive relationships among users, library staff, resources, and services. That connection bodes well for a vital role for ILL, provided ILL practitioners can leverage their request systems and services to successfully facilitate converging and resolving various library services.

CONCLUSION

“Though a seamless electronic interlibrary loan function tends to be the present goal, people are still what make the difference in interlibrary loan service.”9

Although ILL personnel bring many strengths to libraries and their users, one that needs special mention is the fundamentally networked approach to problem solving with users and with colleagues from other libraries. We succeed collectively because we depend on each other and focus on delivering what the user requests. Mentoring programs, like those of the IDS Project (http://idsproject.org) and other library cooperatives, will mature in order to accelerate the implementation and sharing of optimized and innovative workflow. Library networks will significantly improve regional professional development to leverage and reinforce local strengths and will expedite developing and sharing expertise in order to make scalable and strategic workflow change effectively and rapidly with the information environment.

ILL practitioners must agree that our operations are no longer just library-to-library transactions. Rather, collectively, we must optimize information delivery services and explore new ways to support users so they can achieve their goals.

We must retain our strengths as successful advanced problem solvers and searchers, willing to innovate, adapt, and redesign our services around user requests. We can do this by asking, “What are users trying to achieve?” and “How can we best serve them?” We must actively shape our service, systems, and workflow, and continue the tradition of effective communication and networking. The expertise we collectively develop is often supported by mentoring and sharing practices and tools. What makes ILL so unique is the scale to which our work is not limited by geography, and the level of shared commitment to best practices exemplifies the role of libraries serving their communities beyond expectations. The future of ILL is being shaped by customer relations and request management strategies.

NOTES

1. Martha Kyrillidou and Les Bland, comps. and eds., “Graph 3: Supply and Demand in ARL Libraries, 1986–2008,” ARL Statistics 2007–2008 (Washington, DC: Association of Research Libraries, 2009), 13, www.arl.org/bm~doc/arlstat08.pdf.

2. Michael Levine-Clark, “An Analysis of Used-Book Availability on the Internet,” Library Collections, Acquisitions, and Technical Services 28, no. 3 (2004): 283–97; and R. Holley and K. Ankem, “The Effect of the Internet on the Out-of-Print Book Market: Implications for Libraries,” Library Collections, Acquisitions, and Technical Services 29, no. 2 (2005): 118–39.

3. Heather Morrison, “The Dramatic Growth of Open Access: Implications and Opportunities for Resource Sharing,” Journal of Interlibrary Loan, Document Delivery and Electronic Reserve 16, no. 3 (2006): 95–107.

4. Renee Reighart and Cyril Oberlander, “Exploring the Future of Interlibrary Loan: Generalizing the Experience of the University of Virginia,” Interlending and Document Supply 36, no. 4 (2008): 184–90.

5. ILLiad Integrated Services, https://prometheus.atlas-sys.com/display/ILLiadAddons/.

6. Danuta Nitecki, “Document Delivery and the Rise of the Automated Midwife,” Resource Sharing and Information Networks 1, no. 3/4 (1984): 95.

7. The “Book Women” of Eastern Kentucky: W.P.A.’s Pack Horse Librarians, www.kykinfolk.com/knott/bookwomen_easternkentucky.htm.

8. Ibid.

9. Virginia Boucher, Interlibrary Loan Practices Handbook, 2nd ed. (Chicago: American Library Association, 1997).

BIBLIOGRAPHY

The “Book Women” of Eastern Kentucky: W.P.A.’s Pack Horse Librarians. www.kykinfolk.com/knott/bookwomen_easternkentucky.htm.

Boucher, Virginia. Interlibrary Loan Practices Handbook. 2nd ed. Chicago: American Library Association, 1997.

Holley, R., and K. Ankem. “The Effect of the Internet on the Out-of-Print Book Market: Implications for Libraries.” Library Collections, Acquisitions, and Technical Services 29, no. 2 (2005): 118–39.

ILLiad Integrated Services. https://prometheus.atlas-sys.com/display/ILLiadAddons/.

Kyrillidou, Martha, and Les Bland, comps. and eds. “Graph 3: Supply and Demand in ARL Libraries, 1986–2008.” ARL Statistics 2007–2008. Washington, DC: Association of Research Libraries, 2009, 13. www.arl.org/bm~doc/arlstat08.pdf.

Levine-Clark, Michael. “An Analysis of Used-Book Availability on the Internet.” Library Collections, Acquisitions, and Technical Services 28, no. 3 (2004): 283–97.

Morrison, Heather. “The Dramatic Growth of Open Access: Implications and Opportunities for Resource Sharing.” Journal of Interlibrary Loan, Document Delivery and Electronic Reserve 16, no. 3 (2006): 95–107.

Nitecki, Danuta. “Document Delivery and the Rise of the Automated Midwife.” Resource Sharing and Information Networks 1, no. 3/4 (Spring/Summer 1984): 95.

Reighart, Renee, and Cyril Oberlander. “Exploring the Future of Interlibrary Loan: Generalizing the Experience of the University of Virginia.” Interlending and Document Supply 36, no. 4 (2008): 184–90.